Abstract

Background

No previous study has investigated the associations of depression, anxiety, and insomnia at baseline with disability at a five-year follow-up point among outpatients with chronic low back pain (CLBP). The study aimed to simultaneously compare the associations of depression, anxiety, and sleep quality at baseline with disability at a 5-year follow-up point among patients with CLBP.

Methods

Two-hundred and twenty-five subjects with CLBP were enrolled at baseline, and 111 subjects participated at the five-year follow-up point. At follow-up, the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) and total months of disability (TMOD) over the past five years were used as the indices of disability. The depression (HADS-D) and anxiety (HADS-A) subscales of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) were used to assess depression, anxiety, and insomnia at baseline and follow-up. Multiple linear regression was employed to test the associations.

Results

The scores of the HADS-D, HADS-A, and ISI were correlated with the ODI at the same time points (both at baseline and follow-up). A greater severity on the HADS-D, an older age, and associated leg symptoms at baseline were independently associated with a greater ODI at follow-up. A greater severity on the HADS-A and fewer educational years at baseline were independently associated with a longer TMOD. The associations of the HADS-D and HADS-A at baseline with disability at follow-up were greater than that of the ISI at baseline, based on the regression models.

Conclusion

Greater severities of depression and anxiety at baseline were significantly associated with greater disability at the five-year follow-up point. The associations of depression and anxiety at baseline with disability at the long-term follow-up point might be greater than that of insomnia at baseline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Back pain is a leading cause of disability [1] and the second most common reason for physician visits [2]. Predicting factors of chronic low back pain (CLBP) disability have been identified, such as body mass index (BMI), pain level, educational level, muscular strength and endurance, physical demands in the workplace, and social functioning [3,4,5,6]. Previous studies showed that depression, anxiety, and sleep problems are associated with disability [7,8,9,10] and work outcomes [11,12,13], and hinder recovery from disabling back pain [4, 14,15,16,17] among patients with CLBP.

The associations of depression, anxiety, and sleep quality at baseline with CLBP at long-term follow-up have not been clarified well. Most prospective studies followed-up the outcomes of CLBP with a short-term duration of 3 months to 2 years [8, 9, 11,12,13]. Although there are some studies with a follow-up duration longer than 2 years, these studies did not analyze depression, anxiety, and sleep problems simultaneously [5, 18]. Depression and anxiety are known to have long-term and fluctuating courses [19], and it is unclear whether they continue to impact disability at the 5-year follow-up point. Some cross-sectional studies have separately analyzed the relationships of depression, anxiety, and insomnia with CLBP [7, 20, 21], but they were not prospective and did not simultaneously investigate the impacts of depression, anxiety, and sleep quality among patients with CLBP.

Therefore, our study aimed to investigate the associations of depression, anxiety, and sleep quality at baseline with disability at a five-year follow-up point among patients with CLBP. The issue is important, because CLBP causes negative impacts on personal, social, and financial functioning [22], and understanding the important prognostic factors of disability is the first step by which to prevent it. We hypothesized that depression, anxiety, and sleep quality would be associated with disability at the five-year follow-up point among patients with CLBP; moreover, the impacts of depression and anxiety on disability might be greater than that of sleep quality.

Methods

Participants

The research was performed at the general orthopedics clinic in Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Linkou, a medical center in Taiwan. At baseline (from August 2008 to November 2010), subjects were considered eligible if they were within 20–65 years of age and had suffered from LBP for at least 12 weeks, and had made a first visit to the orthopedics clinic. In this study, CLBP was defined as back pain with a duration of more than 12 weeks between the lower ribs and above the gluteal folds, with or without leg pain [23]. The exclusion criteria were patients who (1) had taken antipsychotics or antidepressants within the past one month, and (2) suffered from mental retardation, psychotic symptoms, or severe cognitive impairment with obvious difficulty in being interviewed. Physical examinations were performed and the findings of plain radiographs were diagnosed by a board-certified orthopedist after enrollment. Moreover, the subjects were interviewed by a board-certified psychiatrist who was blind to the data associated with CLBP. The board-certified psychiatrist used the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Axis I Disorders to diagnose major depressive disorder (MDD) [24].

The program was an observational study. Treatment was not controlled, and the patients were treated as general orthopedics outpatients. Some patients discontinued treatment due to improvement or other reasons during the five-year period.

Five years later, the follow-up study was performed from August 2013 to July 2015. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, based on the guidelines regulated in the Declaration of Helsinki, prior to study enrollment. The investigation was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the same hospital.

Assessment of depression, anxiety, sleep quality, and pain

The severities of depression and anxiety were evaluated using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [25]. The HADS, which does not include any somatic symptoms and can assess depression and anxiety severity simultaneously, is composed of seven items for the depression (HADS-D) and anxiety (HADS-A) subscales [25, 26]. The total score of the HADS ranges from 0 to 21 for the two subscales.

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), a 7-item scale, has good reliability and validity to evaluate the severity of insomnia in the past two weeks [27, 28]. Each item of the ISI is rated on a 5-point scale and summed to generate a total score that ranges from 0 to 28. The visual analogue scale (VAS), with 0 representing “no pain” and 10 representing “pain as severe as I can imagine”, was used to evaluate the average pain intensity of LBP in the past 7 days. The HADS, ISI, and VAS were self-administered questionnaires completed by the participants. Higher scores on the HADS-D, HADS-A, and ISI indicate a greater severity of symptoms.

Assessment of disability

Disability associated with CLBP was measured using the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), which was considered as the major outcome. Moreover, self-reported total months of disability (TMOD) due to CLBP over the past 5 years was used as the secondary outcome.

The Oswestry Disability Questionnaire, which includes 10 items, evaluates back or leg pain-related disability in daily life [29, 30]. The score of the questionnaire ranges from 0 to 50, and is usually multiplied by 2 to obtain the ODI. The ODI was used as the primary outcome in this study because it is of sufficient reliability and validity, and is the most commonly-used functional outcome tool for LBP [30].

Patients were requested to report TMOD in employment and/or domestic work due to LBP over the past 5 years. The self-reported TMOD was used because the ODI evaluates the degree of disability in recent daily activities at the follow-up point and the TMOD represents the total duration of disability over the past five years.

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (International Business Machines Corporation, United States) version 20.0 for Windows. The independent t-test, paired t-test, Chi-square test, Pearson’s correlation, and McNemar’s test were used appropriately. Multiple linear regression with the Forward method was employed to determine the associations of severities of depression, anxiety, and insomnia at baseline with the two indices of disability at the follow-up point. The first and second models tested the associations of depression, anxiety, and insomnia with the ODI and TMOD, respectively. Therefore, the dependent variables in the first and second models were the ODI and TMOD, respectively. In the first model, the independent variables included five demographic variables (age, gender, educational years, marital status, and employment status) at baseline and 10 other variables at baseline, including the HADS-D and HADS-A scores, ISI score, ODI, pain intensity (VAS), with life-time MDD history or not, with past surgical history or not, with abnormal radiographic findings or not, with obesity (BMI ≥ 25) [31] or not, and with associated leg symptoms or not. In the second model, the independent variables were the same as in the first model. In all statistical analyses, a two-tailed test with a P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Subjects

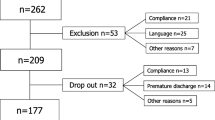

At baseline, 225 patients were enrolled (122 males and 103 females) in the study. During the 5-year period, some patients stopped treatment or dropped out. At the 5-year follow-up point, 111 (49.3%) patients, including 46 women and 65 men, agreed to participate and 114 (50.7%) patients did not attend follow-up for the following reasons: 35 (15.6%) could not be contacted by mail or phone; 79 (35.1%) refused to enter the follow-up program.

There were no significant differences in demographic variables at baseline, except for marital status, between the patients with and without follow-up (Table 1). There were also no significant differences in the severities of depression, anxiety, sleep quality, pain intensity, and disability (ODI score), nor the percentages of other clinical variables, at baseline between the two subgroups. At the follow-up point, the TMOD was 9.1 ± 17.5 months among those who participated at follow-up.

Among the 111 subjects with follow-up, abnormal radiographic findings included spondylosis without instability (47.7% and 37.8% at baseline and follow-up, respectively), spondylolisthesis (13.5% and 17.1%), spondylolysis (13.5% and 10.8%), scoliosis (5.4% and 8.1%), and other findings (12.6% and 28.8%). In the follow-up subgroup, 28 (25.2%) subjects accepted surgical operations for CLBP. Over the five years, 5 (4.5%) subjects were treated in psychiatric clinics. Over the past one year, 25 and 42 (22.5% and 37.8%) subjects accepted treatment in rehabilitation and traditional Chinese medicine clinics, respectively, and 32 (28.2%) subjects took analgesics for CLBP.

Differences in clinical variables at baseline and follow-up among subjects who participated at follow-up

Table 1 shows a significantly decreased pain intensity (p < 0.001), ODI score (p < 0.001), HADS-D score (p = 0.03), and HADS-A score (p < 0.001) at the follow-up point as compared with baseline. There was an increased mean value of BMI (p < 0.001), and increased percentages of obesity (p = 0.003), life-time history of MDD (p < 0.01), associated leg symptoms (p = 0.02), and past history of surgical operation (p < 0.001) at follow-up.

Differences in disability, depression, and anxiety at the follow-up point between subjects with and without clinical variables at baseline

Table 2 shows that subjects with MDD at baseline had a significantly higher ODI (p = 0.03) and significantly higher severities of depression (p < 0.01), anxiety (p = 0.03), and insomnia (p < 0.01) at the follow-up point. Subjects with a history of surgical operation and associated leg symptoms at baseline had a significantly higher depressive severity (p = 0.02) and ODI (p = 0.01) at the follow-up point, respectively.

Correlations of depression, anxiety, and insomnia with the ODI at the same time points

At baseline, the severities of depression (r = 0.46, p < 0.001), anxiety (r = 0.30, p < 0.01), and sleep quality (r = 0.26, p < 0.01) were correlated with the ODI at the same time point among those who participated at follow-up (n = 111). At follow-up, the severities of depression (r = 0.41, p < 0.001), anxiety (r = 0.32, p = 0.001), and sleep quality (r = 0.54, p < 0.001) were also correlated with the ODI at the same time point.

Correlations of continuous variables at baseline with disability, depression, and anxiety at the follow-up point

The correlations of all clinical continuous variables, except for the ISI at baseline, with the ODI at follow-up were significant (P < 0.05) and slightly correlated (r = 0.2–0.4) (Table 3). Educational years (p = 0.001) and the severity of depression (p = 0.04) were slightly correlated with the TMOD at follow-up. The severities of depression, anxiety, pain intensity, and sleep quality at baseline were significantly correlated with the same indices at follow-up.

Independent factors at baseline associated with disability at follow-up

Table 4 shows that subjects with a greater severity of depression, an older age, and associated leg symptoms at baseline were independently associated with a higher ODI at the follow-up point. The first regression model demonstrated that increases of one point on the HADS-D and one year of age at baseline were associated with increases of 1.15 and 0.34 points on the ODI at follow-up, respectively. Moreover, the HADS-D, age, and with associated leg symptoms could explain 11%, 10%, and 5% of the variance in the ODI at follow-up, respectively. The severity of depression had the highest R square change (R square = 0.11). The second regression model showed that fewer educational years and a higher anxiety severity were independently associated with a higher TMOD. Increases of one year of education and one point on the HADS-A at baseline were associated with a decrease of 1.94 and an increase of 1.08 months of TMOD at follow-up, respectively. Educational years and the HADS-A score could explain 10% and 6% of the variance in the TMOD at follow-up, respectively.

Discussion

The first regression model demonstrated that a greater severity of depression at baseline was related to a higher ODI at the 5-year follow-up point. Table 3 shows that the correlation of the HADS-D at baseline with the ODI at follow-up had the highest correlation co-efficiency as compared with other variables at baseline with the ODI at follow-up. Previous studies also showed that depression at baseline was associated with a poorer functional outcome and less possibility of recovering from CLBP [5, 8, 9, 18]. Our results further demonstrated that depression had chronic and long-term negative impacts on the prognosis of CLBP at the 5-year follow-up point.

Depression may be responsible for the development and maintenance of self-reported pain and disability [32, 33], which removes the ability of patients to cope with physical problems. Besides, symptoms of depression such as negative perceptions, especially fear and catastrophizing, anhedonia, fatigue, psychomotor retardation, and social-behavioral withdrawal, are significantly mediated by the relationship between pain and disability, and affect the capability of returning to daily life or work [7, 34, 35]. Another theory suggests that some genetic factors are associated with the relationship between lifetime LBP and depression [36, 37].

The second regression model showed that a greater severity of anxiety at baseline was also associated with a longer TMOD at follow-up. Anxiety increases the risk of acute LBP developing into CLBP [38], and is meanwhile a barrier for treatment adherence in chronic pain conditions [4]. A higher level of anxiety or pain catastrophizing is associated with the fear avoidance model and induces pain-related functional disability [39,40,41]. Our results demonstrated that anxiety at baseline was also an important factor associated with long-term negative outcomes among patients with CLBP.

Several points were worthy of note: (1) The severities of depression, anxiety, and insomnia were correlated with the ODI at the same time points. This was compatible with previous studies [15, 17]. However, the regression model showed that insomnia at baseline was not a significant factor associated with the two indices of disability at follow-up. This might demonstrate that the severities of depression and anxiety at baseline had a higher power to predict disability at follow-up as compared with insomnia at baseline. (2) The second regression model showed that greater educational years was associated with a lower TMOD (Table 4). CLBP patients with a lower educational level have a higher chance of obtaining a job with a greater physical workload [42, 43], which may interfere with treatment adherence [44], the severity of CLBP symptoms, and the possibility of returning to work [45]. Moreover, CLBP patients with a lower educational level might find health information to be less accessible [46]. (3) The regression model demonstrated that associated leg symptoms at baseline was related to a higher ODI at follow-up. Previous study showed that CLBP patients with associated leg symptoms had a poorer prognosis, higher disability, and a poorer quality of life, and used more health resources as compared with those without associated leg symptoms [47].

There were several limitations of this study. (1) All subjects were enrolled from one medical center. Our study had a smaller sample size as compared with one previous long-term follow-up study of patients with CLBP [5]. Although there were no significant differences in the severities of the ODI, pain intensity, HADS-D, HADS-A, and ISI at baseline between subjects with and without follow-up, unknown bias might exist and cause confounding effects. Therefore, expansion of the results to the general population should be performed cautiously. (2) The TMOD was a self-reported measure and might have been affected by recall bias. In fact, one previous study reported recall bias to be an important confounding factor [48], especially under a long recall period. Therefore, interpretation of our results should be performed carefully. (3) Subjects’ treatments were not controlled over the five years. Time-series data on interventions for CLBP were not available. There was a possibility that different treatments might have interfered with the long-term outcomes.

Conclusion

Greater severities of depression and anxiety at baseline were significantly associated with a higher ODI and a longer TMOD at the five-year follow-up point, respectively. Even controlling for the ODI at baseline, the severity of depression at baseline was still associated with the ODI at follow-up. The associations of depression and anxiety at baseline with disability at the long-term follow-up point might be greater than that of insomnia at baseline.

Data availability

The datasets in the current study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- CLBP:

-

Chronic low back pain

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- LBP:

-

Low back pain

- MDD:

-

Major depressive disorder

- HADS-D:

-

Depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- HADS-A:

-

Anxiety subscale of the HADS

- ISI:

-

Insomnia Severity Index

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

- ODI:

-

Oswestry Disability Index

- TMOD:

-

Total months of disability

References

Alleva J, Hudgins T, Belous J, Kristin Origenes A. Chronic low back pain. Dis Mon. 2016;62(9):330–3.

Licciardone JC. The epidemiology and medical management of low back pain during ambulatory medical care visits in the United States. Osteopath Med Prim Care. 2008;2:11.

Elgaeva EE, Tsepilov Y, Freidin MB, Williams FMK, Aulchenko Y, Suri P. ISSLS Prize in Clinical Science 2020. Examining causal effects of body mass index on back pain: a mendelian randomization study. Eur Spine J. 2020;29(4):686–91.

Tagliaferri SD, Miller CT, Owen PJ, Mitchell UH, Brisby H, Fitzgibbon B, et al. Domains of chronic low back Pain and assessing treatment effectiveness: a clinical perspective. Pain Pract. 2020;20(2):211–25.

Nordstoga AL, Nilsen TIL, Vasseljen O, Unsgaard-Tøndel M, Mork PJ. The influence of multisite pain and psychological comorbidity on prognosis of chronic low back pain: longitudinal data from the norwegian HUNT study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e015312.

Steenstra IA, Munhall C, Irvin E, Oranye N, Passmore S, Van Eerd D, et al. Systematic review of prognostic factors for return to work in workers with sub Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27(3):369–81.

Marshall PWM, Schabrun S, Knox MF. Physical activity and the mediating effect of fear, depression, anxiety, and catastrophizing on pain related disability in people with chronic low back pain. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7):e0180788.

Melloh M, Elfering A, Chapple CM, Käser A, Rolli Salathé C, Barz T, et al. Prognostic occupational factors for persistent low back pain in primary care. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2013;86(3):261–9.

Melloh M, Elfering A, Käser A, Salathé CR, Barz T, Aghayev E, et al. Depression impacts the course of recovery in patients with acute low-back pain. Behav Med. 2013;39(3):80–9.

Hung CI, Liu CY, Fu TS. Depression: an important factor associated with disability among patients with chronic low back pain. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2015;49(3):187–98.

Hiebert R, Campello MA, Weiser S, Ziemke GW, Fox BA, Nordin M. Predictors of short-term work-related disability among active duty US Navy personnel: a cohort study in patients with acute and subacute low back pain. Spine J. 2012;12(9):806–16.

Melloh M, Elfering A, Salathé CR, Käser A, Barz T, Röder C, et al. Predictors of sickness absence in patients with a new episode of low back pain in primary care. Ind Health. 2012;50(4):288–98.

Reme SE, Shaw WS, Steenstra IA, Woiszwillo MJ, Pransky G, Linton SJ. Distressed, immobilized, or lacking employer support? A sub-classification of acute work-related low back pain. J Occup Rehabil. 2012;22(4):541–52.

Chou R, Shekelle P. Will this patient develop persistent disabling low back pain? JAMA. 2010;303(13):1295–302.

Lee NK, Jeon SW, Heo YW, Shen F, Kim HJ, Yoon IY, et al. Sleep disturbance in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: Association with disability and quality of life. Clin Spine Surg. 2020;33(4):E185–e90.

Skarpsno ES, Mork PJ, Nilsen TIL, Nordstoga AL. Influence of sleep problems and co-occurring musculoskeletal pain on long-term prognosis of chronic low back pain: the HUNT study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020;74(3):283–9.

Pakpour AH, Yaghoubidoust M, Campbell P. Persistent and developing sleep problems: a prospective cohort study on the relationship to poor outcome in patients attending a Pain Clinic with Chronic Low Back Pain. Pain Pract. 2018;18(1):79–86.

Kerr D, Zhao W, Lurie JD. What are long-term predictors of outcomes for lumbar disc herniation? A randomized and observational study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(6):1920–30.

Hung CI, Liu CY, Yang CH, Gan ST. Comorbidity with more anxiety disorders associated with a poorer prognosis persisting at the 10-year follow-up among patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2020;260:97–104.

Ho KKN, Simic M, Småstuen MC, Pinheiro MdB, Ferreira PH, Johnsen MB, et al. The association between insomnia, c-reactive protein, and chronic low back pain: cross-sectional analysis of the HUNT study, Norway. Scand J Pain. 2019;19(4):765–77.

Bilterys T, Siffain C, De Maeyer I, Van Looveren E, Mairesse O, Nijs J et al. Associates of Insomnia in people with chronic spinal Pain: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2021;10(14).

Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F, et al. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(6):2028–37.

Wells C, Kolt GS, Marshall P, Bialocerkowski A. The definition and application of Pilates exercise to treat people with chronic low back pain: a Delphi survey of australian physical therapists. Phys Ther. 2014;94(6):792–805.

Bell CC. DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. JAMA. 1994;272(10):828–9.

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77.

Lee CP, Chou YH, Liu CY, Hung CI. Dimensionality of the chinese hospital anxiety depression scale in psychiatric outpatients: Mokken scale and factor analyses. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2017;21(4):283–91.

Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2(4):297–307.

Alsaadi SM, McAuley JH, Hush JM, Bartlett DJ, Henschke N, Grunstein RR, et al. Detecting insomnia in patients with low back pain: accuracy of four self-report sleep measures. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:196.

Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(22):2940–52. discussion 52.

Lee CP, Fu TS, Liu CY, Hung CI. Psychometric evaluation of the Oswestry Disability Index in patients with chronic low back pain: factor and mokken analyses. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):192.

Lim JU, Lee JH, Kim JS, Hwang YI, Kim TH, Lim SY, et al. Comparison of World Health Organization and Asia-Pacific body mass index classifications in COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:2465–75.

Pinheiro MB, Ferreira ML, Refshauge K, Maher CG, Ordoñana JR, Andrade TB, et al. Symptoms of depression as a prognostic factor for low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J. 2016;16(1):105–16.

Wong JJ, Tricco AC, Côté P, Liang CY, Lewis JA, Bouck Z, et al. Association between depressive symptoms or Depression and Health Outcomes for Low Back Pain: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(5):1233–46.

Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Patten SB, Freedman G, Murray CJ, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10(11):e1001547.

Slavich GM, Irwin MR. From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: a social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychol Bull. 2014;140(3):774–815.

Pinheiro MB, Ferreira ML, Refshauge K, Colodro-Conde L, Carrillo E, Hopper JL, et al. Genetics and the environment affect the relationship between depression and low back pain: a co-twin control study of spanish twins. Pain. 2015;156(3):496–503.

Suri P, Boyko EJ, Smith NL, Jarvik JG, Williams FM, Jarvik GP, et al. Modifiable risk factors for chronic back pain: insights using the co-twin control design. Spine J. 2017;17(1):4–14.

Hallegraeff JM, Kan R, van Trijffel E, Reneman MF. State anxiety improves prediction of pain and pain-related disability after 12 weeks in patients with acute low back pain: a cohort study. J Physiother. 2020;66(1):39–44.

Butowicz CM, Silfies SP, Vendemia J, Farrokhi S, Hendershot BD. Characterizing and understanding the low back Pain Experience among Persons with Lower Limb loss. Pain Med. 2020;21(5):1068–77.

Oliveira DS, Vélia Ferreira Mendonça L, Sofia Monteiro Sampaio R, Manuel Pereira Dias de Castro-Lopes J, Ribeiro de Azevedo LF. The impact of anxiety and depression on the Outcomes of Chronic Low Back Pain Multidisciplinary Pain Management-A Multicenter prospective cohort study in Pain clinics with one-year follow-up. Pain Med. 2019;20(4):736–46.

Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2356–67.

Schrijvers CT, van de Mheen HD, Stronks K, Mackenbach JP. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in the working population: the contribution of working conditions. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27(6):1011–8.

Warren JR, Hoonakker P, Carayon P, Brand J. Job characteristics as mediators in SES-health relationships. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(7):1367–78.

Dhondt E, Van Oosterwijck J, Cagnie B, Adnan R, Schouppe S, Van Akeleyen J, et al. Predicting treatment adherence and outcome to outpatient multimodal rehabilitation in chronic low back pain. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2020;33(2):277–93.

Monika H, Rui D, Sharon C, Michelle M, Michaela C, Martin W et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of predictors of return to work after spinal surgery for chronic low back and leg pain. J Pain. 2022.

Ross CE, Wu C-l. The links between Education and Health. Am Sociol Rev. 1995;60(5):719–45.

Konstantinou K, Hider SL, Jordan JL, Lewis M, Dunn KM, Hay EM. The impact of low back-related leg pain on outcomes as compared with low back pain alone: a systematic review of the literature. Clin J Pain. 2013;29(7):644–54.

Coughlin SS. Recall bias in epidemiologic studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(1):87–91.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ping-Hsuan Huang for the statistical assistance and wish to acknowledge the support of the Maintenance Project of the Center for Big Data Analytics and Statistics (Grant CLRPG3N0011) at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital for study design and monitor, data analysis and interpretation.

Funding

This study was supported in part by Chang Gung Memorial Hospital Research Programs (CMRPG3H1781, CMRPG3L1541, and CMRPG3M1801) and Ministry of Science and Technology Research Programs (NSC 102-2314-B-182A007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CIH and TSF contributed to the study conception and design. All authors collected the data. Data analysis was performed by CIH and LYW. The first draft of the manuscript was written by LYW and CIH. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (reference number: 1014738B, approved on 2013/01/24). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, based on the guidelines regulated in the Declaration of Helsinki, prior to study enrollment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, LY., Fu, TS., Tsia, MC. et al. The associations of depression, anxiety, and insomnia at baseline with disability at a five-year follow-up point among outpatients with chronic low back pain: a prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 24, 565 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-023-06682-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-023-06682-6