Abstract

Background

Chronic pain is a disabling condition which is prevalent in about 20% of the adult population. Physiotherapy is the most common non-pharmacological treatment option for chronic pain, but often demonstrates unsatisfactory outcomes. Virtual Reality (VR) may offer the opportunity to complement physiotherapy treatment. As VR has only recently been introduced in physiotherapy care, it is unknown to what extent VR is used and how it is valued by physiotherapists. The aim of this study was to analyse physiotherapists’ current usage of, experiences with and physiotherapist characteristics associated with applying therapeutic VR for chronic pain rehabilitation in Dutch primary care physiotherapy.

Methods

This online survey applied two rounds of recruitment: a random sampling round (873 physiotherapists invited, of which 245 (28%) were included) and a purposive sampling round (20 physiotherapists using VR included). Survey results were reported descriptively and physiotherapist characteristics associated with VR use were examined using multivariable logistic regression analysis.

Results

In total, 265 physiotherapists participated in this survey study. Approximately 7% of physiotherapists reported using therapeutic VR for patients with chronic pain. On average, physiotherapists rated their overall experience with therapeutic VR at 7.0 and “whether they would recommend it” at 7.2, both on a 0–10 scale. Most physiotherapists (71%) who use therapeutic VR started using it less than two years ago and use it for a small proportion of their patients with chronic pain. Physiotherapists use therapeutic VR for a variety of conditions, including generalized (55%), neck (45%) and lumbar (37%) chronic pain. Physiotherapists use therapeutic VR mostly to reduce pain (68%), improve coordination (50%) and increase physical mobility (45%). Use of therapeutic VR was associated with a larger physiotherapy practice (OR = 2.38, 95% CI [1.14–4.98]). Unfamiliarity with VR seemed to be the primary reason for not using VR.

Discussion

Therapeutic VR for patients with chronic pain is in its infancy in Dutch primary care physiotherapy practice as only a small minority uses VR. Physiotherapists that use therapeutic VR are modestly positive about the technology, with large heterogeneity between treatment goals, methods of administering VR, proposed working mechanisms and chronic pain conditions to treat.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Approximately one in five adults suffer from chronic pain [1], which mostly occurs in the lower back [2]. Chronic pain is defined as pain lasting longer than three months and is often caused and sustained by a complex interplay of biological, psychological and social factors [3]. Patients with chronic pain report lower quality of life, more social problems, depression and other mental complaints [2, 4] compared to people without chronic pain. Moreover, chronic pain is associated with high direct and indirect societal costs [5].

Treatment options for patients with chronic pain are diverse and include both pharmacological and non-pharmacological possibilities, of which physiotherapy is the most common non-pharmacological treatment [1, 2]. It is recommended to administer stepped care for patients with chronic pain, meaning that treatment modalities of more basic steps (e.g. education, resume normal activities) should be applied before advanced treatment modalities (e.g. physical or psychological therapy) can be considered [6]. During their patient journey, most patients with chronic pain visit a physiotherapist to receive exercises and patient education [1, 2]. However, effects of this treatment are often small to moderate and diminish over time [7, 8], partly due to a lack of treatment adherence of patients [9]. Virtual Reality (VR) could offer a possibility to support physiotherapists in their treatment of patients with chronic pain, amongst other potential mechanisms by motivating patients to keep exercising [10].

VR is an emerging technology in healthcare [11], and is defined as an interactive, 3D computer-generated program in a multimedia environment [12]. VR can be categorized as either immersive or non-immersive, in which immersion usually evokes a greater sense of presence and feeling of being there in the virtual environment (VE). In immersive VR, the user wears equipment, like a head-mounted display (HMD), through which the VE is delivered. In non-immersive VR, the VE is usually delivered through a computer or television screen and controlled using a joystick or other device [13, 14]. Besides motivating patients, proposed working mechanisms of VR for chronic pain include distraction [15], graded exposure therapy [16], relaxation [17] and neurophysiologic alterations [18]. VR has shown to be an effective therapeutic tool in several chronic pain conditions, including fibromyalgia [19, 20], complex regional pain syndrome [21] and chronic low back pain [22, 23]. Besides this, VR in primary care physiotherapy offers possibilities including patient monitoring and at-home treatment, while also offering physiotherapy practices the opportunity to present themselves as innovative [24, 25]. Given the rising healthcare costs, VR could be a useful tool in the treatment of the growing population of patients with chronic pain, by acting as a substitute for treatment or enhancing current treatments as a complementary treatment modality. Moreover, a recent publication by the Dutch Society for Physical Therapy (KNGF) stated that physiotherapy treatment of patients with chronic pain should focus on three core elements: education, self-management and promoting healthy activity behaviour [26]. VR could be of use to aid with each of these goals.

Despite the widespread attention for VR as a treatment tool in chronic pain science and physiotherapy practice, it is not clear to what extent therapeutic VR is being used in primary care physiotherapy in patients with chronic pain. Moreover, it is unclear what the reasons of physiotherapists are to use or not use therapeutic VR, how VR as a treatment modality is being perceived by physiotherapists, and which physiotherapist characteristics are related to VR usage. Results of this study could provide valuable insights for physiotherapists, researchers, policy makers and VR developers to further improve chronic pain treatment of physiotherapists. The aim of this study was to explore physiotherapists’ current usage of, experiences with and characteristics associated with applying therapeutic VR for chronic pain rehabilitation in Dutch primary care physiotherapy.

Methods

Design and sample

This cross-sectional, survey study is part of the VARIETY project and funded by ZonMw (project number: 10270032021502), as described in the study protocol [27]. Approval of the ethical research committee of our institution was obtained for this study (HAN ECO: 347.04/22) in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants signed online informed consent before participating (tick-box response). The survey data was collected between March and December 2022. This study is reported in line with the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Survey (CHERRIES) [28].

Survey

The online open survey was constructed using Google Forms (Appendix 1). Survey questions were based on literature and refined and pilot tested by the research group, by asking four physiotherapists to complete and comment on the online survey before recruitment of participants started. The survey consisted of five demographic questions (i.e. gender, age, practice size, years’ experience as a physiotherapist, physiotherapy specialization), 14 closed-ended questions for physiotherapists that use therapeutic VR (regarding overall experience with therapeutic VR, patients for which therapeutic VR is applied, method of offering therapeutic VR and working mechanisms regarding therapeutic VR) and eight closed-ended questions for physiotherapists that do not use therapeutic VR (regarding reasons not to use therapeutic VR, patients that could use therapeutic VR and possible working mechanisms of therapeutic VR). The order of the questions was constant, without alternation or randomization, adaptive questioning was used to prevent stating redundant questions, reviewing of questions was possible and all questions needed to be answered before completing the survey. The questions were shown on two screens, using a maximum of 13 questions per screen. The survey took physiotherapists approximately five minutes if they use therapeutic VR and two minutes if not.

Recruitment and sample

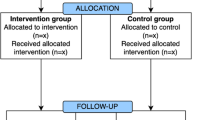

Data was collected using two consecutive rounds (see Fig. 1). The first round used cluster simple random sampling [29] and included Dutch primary care physiotherapists that did and did not use therapeutic VR for patients with chronic pain. For both rounds, physiotherapists were eligible for participation if they were: (1) practicing primary care physiotherapists that were, (2) working in the Netherlands and, (3) accessible online through e-mail or a contact form. The second round followed a purposive sampling methodology [29], aimed at Dutch primary care physiotherapists who applied therapeutic VR for patients with chronic pain.

First round

Participants of the first round of the study were recruited using cluster simple random sampling, in two different regions, namely 40 kms around Arnhem and around Almelo, both cities from the eastern part of the Netherlands. In these two regions, every physiotherapy practice that fulfilled the inclusion criteria was contacted online, regardless if they used therapeutic VR.

Second round

Participants in the second round of the study were recruited nationwide using purposive sampling and invited to participate if they provided therapeutic VR for patients with chronic pain.

Procedure

The initial contact with eligible participants in both rounds consisted of an information letter about the survey and an invitation to voluntarily participate. Two reminders were sent respectively one and two weeks after initial contact to non-responding participants in the first round [30], to reach a minimal retention rate of 25% [31]. All participants voluntarily answered the survey and were not rewarded for participation.

Analysis

The survey results were downloaded and analysed using SPSS version 27 (IBM corporation, Armonk, NY). Demographic characteristics of physiotherapists were presented using means and standard deviations and frequencies. To examine the association between physiotherapist characteristics (i.e. age, gender, practice size, specialization and years of experience) and therapeutic VR use, a multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted. For this analysis, the following physiotherapist characteristics were dichotomized: number of years working as a physiotherapist (≤ 9 or ≥ 10 years), specialization (yes/no) and size of physiotherapy practice (≤ 9 or ≥ 10 physiotherapists). The results to the closed-ended questions were analysed by calculating percentages and presented in tables and graphs using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA). The surveys from the first round were analysed to gain insight in the prevalence of VR use and characteristics for (non)usage of VR. The survey results of only physiotherapists using therapeutic VR from the first round were combined with the survey results from the second round, to analyse experiences with VR.

Results

Inclusion

In total, 873 physiotherapists were invited in the first round. Of these physiotherapists 245 (28%) completed the survey, as shown in Fig. 1. In the second round, 20 physiotherapists that use therapeutic VR completed the survey. All physiotherapists who started the survey completed it.

VR use in physiotherapy practice

From the total of 245 participating physiotherapists from the first round, 18 (7%) stated that they use therapeutic VR in their treatment of patients with chronic pain, as shown in Table 1. In combination with the 20 physiotherapists using VR from the second round, a total of 38 physiotherapists that use therapeutic VR were surveyed.

Physiotherapists (n = 38) that stated they use VR in their treatment of patients with chronic pain scored their overall experience with therapeutic VR at 7.0 (on a 0 (extremely bad) to 10 (extremely good) scale) and whether they would recommend using therapeutic VR at 7.2 (on a 0 (definitely not) tot 10 (definitely yes) scale). Most physiotherapists (71%) started using therapeutic VR less than two years ago and 82% of physiotherapists use VR for a small proportion (< 10%) of their patients with chronic pain. Physiotherapists use VR at the physiotherapy practice only (39%) or both at practice and patient’s home (61%). Multiple proposed working mechanisms of VR were stated, and educating the patient (58%), relaxation (53%) and activation (53%) were most frequently mentioned. The most commonly reported treatment goals when using VR were pain reduction (68%), coordination improvement (50%) and physical mobility improvement (45%). Regarding VR hardware, nearly everybody (97%) uses HMDs, with a preference for Oculus (56%) and Pico (47%) headsets. Regarding VR software, Reducept (Reducept, Leeuwarden, The Netherlands) is the most used software (50%), followed by Corpus VR (inMotion VR, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands) (26%) and SyncVR (SyncVR, Utrecht, The Netherlands) applications (16%). Physiotherapists using therapeutic VR reported it is mostly used for chronic pain patients between 31–50 years old (90%) and 51–70 years old (82%). The main conditions of patients that receive therapeutic VR are musculoskeletal conditions (53%) and medically unexplained physical symptoms (53%). Within musculoskeletal conditions, VR is mostly applied in patients with generalized pain complaints (55%) and nonspecific cervical (45%) and lumbar (37%) pain (see Table 2).

Physiotherapist and practice characteristics associated with therapeutic VR use

Results from the multivariable logistic regression analysis among physiotherapists from round one, showed that working at a larger physiotherapy practice (p = 0.02) was the only physiotherapy characteristic that was associated with therapeutic VR use, while other physiotherapist characteristics (i.e. age, gender, years working as physiotherapist and specialization) were not found to be associated with therapeutic VR use (see Table 3).

Physiotherapists that do not use therapeutic VR

From a total of 227 physiotherapists not using therapeutic VR, only 2% has ever used therapeutic VR before and stopped using it, while 98% never used VR. The main reason for not using therapeutic VR is that physiotherapists were unfamiliar with VR as treatment modality (71%), while costs (20%) and lack of eligible patients for VR (18%) are much less reported as reasons (see Table 4).

Discussion

This survey among 265 physiotherapists across the Netherlands showed that a minority of approximately 7% of Dutch primary care physiotherapists of the sample population currently uses therapeutic VR in their treatment of patients with chronic pain. Unfamiliarity with VR is the primary reason for not using VR. Larger physiotherapy practices seem to be more likely to use VR compared to smaller practices. Physiotherapists are modestly positive about VR as a treatment modality and use VR for a variety of treatment goals.

The limited VR usage found in our large survey corresponds with that of other therapeutic eHealth technology studies in Dutch physiotherapy care [32, 33]. Ehealth has been introduced in the past two decades amongst other reasons as a strategy to reduce health care costs. Despite the introduction of eHealth, costs of healthcare are still rising in the Netherlands. Studies indicate that many physiotherapists, at least in the Netherlands, are still hesitant to incorporate eHealth in their treatment. For example, one study found that only 1% of patients of physiotherapists in the Netherlands received some form of therapeutic eHealth [34].

In this study, working in a larger physiotherapy practice was associated with using therapeutic VR. This is in line with a previous study that found that eHealth use was associated with physiotherapy practice size [33], possibly due to more financial resources. In contrast to this potential facilitator, implementation of VR in healthcare might be hindered due to technical limitations of the device, lack of comparative research and perceived increased work pressure [35,36,37]. Some of these barriers were mentioned by the physiotherapists in this survey, but the main reason for surveyed physiotherapists not using therapeutic VR was that they were unfamiliar with using therapeutic VR. This might be related to underexposure of eHealth in physiotherapy programs, as eHealth for example was not mentioned in a recent Delphi study on pain-related content in the Dutch physiotherapy curriculum [38].

Several treatment goals of therapeutic VR were mentioned by physiotherapists, with reducing pain intensity as most commonly reported treatment goal (68%). Therapeutic VR has indeed been found to be effective in reducing acute pain [39], but for chronic pain, the level of evidence for therapeutic VR is weaker and less available [40, 41]. This is surprising since the survey was specifically about treatment of patients with chronic pain. Another treatment goal reported by 50% of the physiotherapists was improving coordination. This can be considered surprising as well, as not improving coordination, but muscle strength or aerobic capacity are more established treatment goals for chronic pain [42], but reported less by the physiotherapists. On the other hand, it could be more difficult to target these established treatment goals by VR.

Another interesting finding in this survey is that therapeutic VR is used less often in older patients (> 70 years old) compared to younger patients with chronic pain. This is in line with previous studies in which healthcare providers tend to not treat older patients with VR, because of existing ageist beliefs that this population for example does not understand VR technology [43]. However, recent studies found that elderly patients with chronic pain could benefit from treatment with VR [44, 45] and find it an acceptable way to manage their pain [46, 47]. This implies there might be possibilities to enhance treatment of older adults with chronic pain by adding therapeutic VR.

One of the strengths of this study was using two rounds of sampling, which made it possible to gain more insight in the reasons for using and not using VR, and in the experiences with VR. Also, by cluster random sampling in two areas in the Netherlands, it was possible to reach an adequate sample size of surveyed physiotherapists. On the other hand, this study had several limitations that should be noted. First, this study focused specifically on primary care physiotherapists and on patients with chronic pain. It is possible that VR use is different in other healthcare settings and for other patient populations. Another limitation is the small sample size of physiotherapists that use therapeutic VR (n = 38), despite efforts to reach this group of physiotherapists using professionals networks and social media. Also, most of these physiotherapists were not very experienced with therapeutic VR for patients with chronic pain. The combination of this sample size with lack of experience with therapeutic VR could impair the generalizability of results about VR usage in clinical practice. Moreover, even though probability sampling (i.e. cluster random sampling) was used to recruit physiotherapists in the first round, it is possible that sampling bias occurred to some extent. For example, because of an increased likelihood of physiotherapists that use VR to respond to the survey rather than physiotherapists that do not use VR. Finally, the survey only included close-ended questions, which might have hindered the collection of more in-depth qualitative information [48]. We chose this to minimize the time for physiotherapists to finish the survey.

Results of this study indicate that therapeutic VR use is still in its infancy in primary care physiotherapy. One possible reason for the low adoption of VR, next to the reported barriers such as costs, is a lack of high-quality evidence on the effectiveness of therapeutic VR for patients with chronic pain [49]. There were some explorative RCTs on therapeutic VR for patients with chronic pain in physiotherapy settings [50,51,52], but the quality of some of these RCTs is insufficient and limitations to generalize these results include heterogeneity of patient populations and differences between dosage and diversity of used VR software and hardware [53, 54]. Therefore, future research should provide more insights in the (cost-)effectiveness, possible working mechanisms and most suitable patient groups of therapeutic VR for patients with chronic pain, in order to be recommended in clinical guidelines and adopted in clinical practice [49, 55]. Finally, given the novelty and possible increasing usage of therapeutic VR, future research may also focus on replicating the current explorative study after some years to see how therapeutic VR adoption advances in clinical physiotherapy practice [56]. Also, this future research could include open-ended questions to acquire more thorough information and incorporate topics including physiotherapists’ attitudes towards VR, likelihood of VR use and (both physical and mental) symptoms, behaviours and conditions they treat with VR. Finally, for the implementation of VR in physiotherapy care, it would be interesting to gain more insight into values, attitudes and beliefs of physiotherapists that do not use therapeutic VR yet.

Results of this study showed that therapeutic VR for patients with chronic pain is still in its infancy in current Dutch primary care physiotherapy practice, with only 7% of physiotherapists using VR. Unfamiliarity with VR seems to be the primary reason for not using VR. Moreover, larger physiotherapy practices seem to be more likely to use VR compared to smaller practices. This survey also showed that physiotherapists are modestly positive about VR as a treatment modality and that physiotherapists report a large heterogeneity in treatment goals, methods of administering VR, proposed working mechanisms and chronic pain conditions to treat with VR.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated during this study will not be publicly available, but will be available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- HMD:

-

Head-mounted display

- KNGF:

-

Dutch Society for Physical Therapy

- VE:

-

Virtual environment

- VR:

-

Virtual reality

References

Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:287.

Bekkering GE, et al. Epidemiology of chronic pain and its treatment in The Netherlands. Neth J Med. 2011;69:141–53.

Fillingim RB. Individual differences in pain: Understanding the mosaic that makes pain personal. Pain. 2017;158:S11–8.

Solé E, et al. Social factors, disability, and depressive symptoms in adults with chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2020;36:371.

Boonen A, et al. Large differences in cost of illness and wellbeing between patients with fibromyalgia, chronic low back pain, or ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:396–402.

Lin I, et al. What does best practice care for musculoskeletal pain look like? Eleven consistent recommendations from high-quality clinical practice guidelines: systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:79–86.

Hayden JA, Ellis J, Ogilvie R, Malmivaara A, van Tulder MW. Exercise therapy for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;9:CD009790.

Marris D, Theophanous K, Cabezon P, Dunlap Z, Donaldson M. The impact of combining pain education strategies with physical therapy interventions for patients with chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Physiother Theory Pract. 2021;37:461–72.

Nicholas MK, et al. Is adherence to pain self-management strategies associated with improved pain, depression and disability in those with disabling chronic pain? Eur J Pain. 2012;16:93–104.

Ijaz K, Ahmadpour N, Wang Y, Calvo RA. Player Experience of Needs Satisfaction (PENS) in an immersive virtual reality exercise platform describes motivation and enjoyment. Int J Human-Computer Interact. 2020;36:1195–204.

Mallari B, Spaeth EK, Goh H, Boyd BS. Virtual reality as an analgesic for acute and chronic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Res. 2019;12:2053–85.

Pan Z, Cheok AD, Yang H, Zhu J, Shi J. Virtual reality and mixed reality for virtual learning environments. Comput Graph. 2006;30:20–8.

Burdea GC. Virtual rehabilitation–benefits and challenges. Methods Inf Med. 2003;42:519–23.

Negro Cousa E, et al. New frontiers for cognitive assessment: an exploratory study of the potentiality of 360° technologies for memory evaluation. Cyberpsychology Behav Soc Netw. 2019;22:76–81.

Wiederhold BK, Gao K, Sulea C, Wiederhold MD. Virtual reality as a distraction technique in chronic pain patients. Cyberpsychology Behav Soc Netw. 2014;17:346–52.

Trost Z, Parsons TD. Beyond distraction: virtual reality graded exposure therapy as treatment for pain-related fear and disability in chronic pain. J Appl Biobehav Res. 2014;19:106–26.

Rothbaum AO, Tannenbaum LR, Zimand E, Rothbaum BO. A pilot randomized controlled trial of virtual reality delivered relaxation for chronic low back pain. Virtual Real. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-023-00760-9.

Gupta A, Scott K, Dukewich M. Innovative technology using virtual reality in the treatment of pain: does it reduce pain via distraction, or is there more to it? Pain Med Malden Mass. 2018;19:151–9.

Botella C, et al. Virtual reality in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a pilot study. Cyberpsychology Behav Soc Netw. 2013;16:215–23.

Garcia-Palacios A, et al. Integrating virtual reality with activity management for the treatment of fibromyalgia: acceptability and preliminary efficacy. Clin J Pain. 2015;31:564–72.

Sato K, et al. Nonimmersive virtual reality mirror visual feedback therapy and its application for the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome: an open-label pilot study. Pain Med Malden Mass. 2010;11:622–9.

Darnall BD, Krishnamurthy P, Tsuei J, Minor JD. Self-administered skills-based virtual reality intervention for chronic pain: randomized controlled pilot study. JMIR Form Res. 2020;4:e17293.

Garcia LM, et al. An 8-week self-administered at-home behavioral skills-based virtual reality program for chronic low back pain: double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial conducted during COVID-19. J Med Internet Res. 2021;2021232:23.

Kloek CJJ, et al. Physiotherapists’ experiences with a blended osteoarthritis intervention: a mixed methods study. Physiother Theory Pract. 2020;36:572–9.

Nijeweme-d’Hollosy WO, van Velsen L, Huygens M, Hermens H. Requirements for and barriers towards interoperable ehealth technology in primary care. IEEE Internet Comput. 2015;19:10–9.

Köke A, et al. KNGF-standpunt fysiotherapie bij patiënten met pijn. 2022.

Slatman S, Ostelo R, van Goor H, Staal JB, Knoop J. Physiotherapy with integrated virtual reality for patients with complex chronic low back pain: protocol for a pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial (VARIETY study). BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24:132.

Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet E-surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e132.

Hibberts M, Burke Johnson R, Hudson K. Common survey sampling techniques. Handb Surv Methodol Soc Sci. 2012:53–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3876-2_5.

Sánchez-Fernández J, Muñoz-Leiva F, Montoro-Ríos FJ. Improving retention rate and response quality in Web-based surveys. Comput Hum Behav. 2012;28:507–14.

Shih T-H, Fan X. Comparing response rates in e-mail and paper surveys: a meta-analysis. Educ Res Rev. 2009;4:26–40.

Vader MA. eHealth in Dutch physiotherapy practices: a national survey. 2017.

Van der Vaart R, van Tuyl LHD, Versluis A, Wouters MJM, van Deursen L, Standaar L, ... Suijkerbuijk AWM. E-healthmonitor 2022. Stand van zaken digitale zorg. RIVM rapport. 2023. 2022-0153. https://www.nivel.nl/sites/default/files/bestanden/1004360.pdf.

Krijgsman J, Peeters J, Burghouts A. Op naar meerwaarde – eHealth-monitor 2014. Tijdschr Voor Gezondheidswetenschappen. 2015;93:58–9.

Brady N, Dejaco B, Lewis J, McCreesh K, McVeigh JG. Physiotherapist beliefs and perspectives on virtual reality supported rehabilitation for the management of musculoskeletal shoulder pain: a focus group study. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0284445.

Brepohl PCA, Leite H. Virtual reality applied to physiotherapy: a review of current knowledge. Virtual Real. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-022-00654-2.

Halbig A, Babu SK, Gatter S, Latoschik ME, Brukamp K, von Mammen S. Opportunities and Challenges of Virtual Reality in Healthcare – A Domain Experts Inquiry. Front Virtual Real. 2022;3:837616. https://doi.org/10.3389/frvir.2022.837616.

Reezigt R, Beetsma A, Köke A, Hobbelen H, Reneman M. Toward consensus on pain-related content in the pre-registration, undergraduate physical therapy curriculum: a Delphi-study. Physiother Theory Pract. 2022;0:1-14.

Garrett B, et al. A rapid evidence assessment of immersive virtual reality as an adjunct therapy in acute pain management in clinical practice. Clin J Pain. 2014;30:1089.

Ahmadpour N, et al. Virtual Reality interventions for acute and chronic pain management. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2019;114:105568.

Lier EJ, de Vries M, Steggink EM, ten Broek RPG, van Goor H. Effect modifiers of virtual reality in pain management: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Pain. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002883.

Köke AJA, Hilberdink S, Hilberdink WKHA, Reneman MF, Schoffelen T, Heeringen-de Groot D. KNGF-standaard Beweeginterventie chronische pijn. Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap Fysiotherapie (KNGF). 2014. https://www.kngf.nl/kennisplatform/beweeginterventies/chronische-pijn?_hn:type=resource&_hn:ref=r43_r1_r1&_hn:rid=5679473f-8fee-4e49-9299-b7fd6df58082.

Mace RA, Mattos MK, Vranceanu AM. Older adults can use technology: why healthcare professionals must overcome ageism in digital health. Transl Behav Med. 2022:ibac070. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibac070.

Sarkar TD, Edwards RR, Baker N. The feasibility and effectiveness of virtual reality meditation on reducing chronic pain for older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Pain Pract. 2022;22:631–41.

Stamm O, Dahms R, Reithinger N, Ruß A, Müller-Werdan U. Virtual reality exergame for supplementing multimodal pain therapy in older adults with chronic back pain: a randomized controlled pilot study. Virtual Real. 2022;26:1291–305.

Healy D, Flynn A, Conlan O, McSharry J, Walsh J. Older adults’ experiences and perceptions of immersive virtual reality: systematic review and thematic synthesis. JMIR Serious Games. 2022;10:e35802.

Nakad L, Rakel B. (271) Attitudes of older adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain towards immersive virtual reality. J Pain. 2019;20:S42.

Reja U, Manfreda KL, Hlebec V, Vehovar V. Open-ended vs. close-ended questions in web questionnaires. Dev Appl Stat. 2003;19:159–77.

Trost Z, France C, Anam M, Shum C. Virtual reality approaches to pain: toward a state of the science. Pain. 2021;162:325–31.

Afzal MW, et al. Effects of virtual reality exercises and routine physical therapy on pain intensity and functional disability in patients with chronic low back pain. JPMA J Pak Med Assoc. 2022;72:413–7.

Nusser M, Knapp S, Kramer M, Krischak G. Effects of virtual reality-based neck-specific sensorimotor training in patients with chronic neck pain: a randomized controlled pilot trial. J Rehabil Med. 2021;53:jrm00151.

Yilmaz Yelvar GD, et al. Is physiotherapy integrated virtual walking effective on pain, function, and kinesiophobia in patients with non-specific low-back pain? Randomised controlled trial. Eur Spine J. 2017;26:538–45.

Austin PD. The analgesic effects of virtual reality for people with chronic pain: a scoping review. Pain Med Malden Mass. 2022;23:105–21.

Chuan A, Zhou JJ, Hou RM, Stevens CJ, Bogdanovych A. Virtual reality for acute and chronic pain management in adult patients: a narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2021;76:695–704.

Vincent C, Eberts M, Naik T, Gulick V, O’Hayer CV. Provider experiences of virtual reality in clinical treatment. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0259364.

Fullen BM, et al. Musculoskeletal pain: current and future directions of physical therapy practice. Arch Rehabil Res Clin Transl. 2023:100258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arrct.2023.100258.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Nina Schut (HAN), Tobias Eulink (HAN), Kevyn van der Linden (HAN), Wesley Guldenaar (HAN), Britt Landman (Saxion) and Leon ten Holder (Saxion) for their help in collecting the data for the first round. Also, we would like to thank KNGF and MSG Science Network for their help with recruitment for the second round.

Funding

This study was funded by ZonMw (case number: 10270032021502). The funder had no role in the design, organization and execution of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS was the principal investigator of this study and drafted the first version of the manuscript. JBS conceptualized and designed the study, reviewed and revised the manuscript and supervised SS. HG reviewed and revised the manuscript and supervised SS. RO reviewed and revised the manuscript and supervised SS. RS supported recruitment and reviewed and revised the manuscript. JK conceptualized and designed the study, reviewed and revised the manuscript and supervised SS. All authors contributed to the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the ethics committee of the HAN University of Applied Sciences (case number: 347.04/22). Participating physiotherapists provided informed consent before answering the survey.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1: survey

Appendix 1: survey

Questions 1–5: demographic characteristics for all physiotherapists.

Questions 6–19: physiotherapists that use therapeutic VR.

Questions 20–27: physiotherapists that do not use therapeutic VR.

-

1.

What is your gender?

-

a.

Male

-

b.

Female

-

c.

Other

-

a.

-

2.

What size is the physiotherapy practice you work?

-

a.

1

-

b.

2–4

-

c.

5–9

-

d.

10–14

-

e.

15–19

-

f.

20–24

-

g.

25–30

-

h.

Over 30

-

a.

-

3.

How long do you work as a physiotherapists?

-

a.

0–4 years

-

b.

5–9 years

-

c.

10–14 years

-

d.

15–19 years

-

e.

20 years or longer

-

a.

-

4.

What is your age? (open question)

-

5.

Did you specialize as a physiotherapist?*

-

a.

No, I am a regular physiotherapist

-

b.

Yes, as a paediatric physiotherapist

-

c.

Yes, as a manual physiotherapist

-

d.

Yes, as a sports physiotherapist

-

e.

Yes, as a psychosomatic physiotherapist

-

f.

Yes, as a pelvic physiotherapist

-

g.

Yes, other (open question)

-

a.

-

6.

Did you use therapeutic VR for patients with CMP in the past year?

-

a.

Yes

-

b.

No

-

a.

-

7.

What is your general experience with therapeutic VR in your physiotherapy treatment? (scale from 0 (very bad) to 10 (very good))

-

8.

To what extent would you recommend therapeutic VR to a colleague physiotherapist? (scale from 0 (would definitely not recommend) to 10 (would definitely recommend))

-

9.

How long have you used therapeutic VR?

-

a.

< 1 year

-

b.

1–2 years

-

c.

3–5 years

-

d.

> 5 years

-

a.

-

10.

For what age groups do you use therapeutic VR?*

-

a.

< 18 year

-

b.

18–30 years

-

c.

31–50 years

-

d.

51–70 years

-

e.

> 71 years

-

a.

-

11.

For which conditions do you use therapeutic VR?*

-

a.

Musculoskeletal conditions

-

b.

Medically unexplained physical symptoms

-

c.

Heart, arterial or lung conditions

-

d.

Neurological conditions

-

e.

Geriatric conditions

-

f.

Oncology

-

g.

Paediatric conditions

-

h.

Other

-

a.

-

12.

For which musculoskeletal conditions do you use therapeutic VR?*

-

a.

Nonspecific cervical complaints

-

b.

Nonspecific (low) back pain

-

c.

Arthritis

-

d.

Headache or dizziness

-

e.

Pelvic or hip complaints

-

f.

Shoulder or arm complaints

-

g.

Fibromyalgia

-

h.

Generalized pain complaints

-

i.

Other

-

a.

-

13.

For how many patients with CMP do you use therapeutic VR as percentage of your total patient population?

-

a.

0–10%

-

b.

11–25%

-

c.

26–40%

-

d.

41–60%

-

e.

61–75%

-

f.

76–80%

-

g.

Over 80%

-

a.

-

14.

How do you administer therapeutic VR?

-

a.

Only at practice

-

b.

Only at home

-

c.

Both

-

a.

-

15.

For which possible working mechanism(s) do you use therapeutic VR?*

-

a.

Education

-

b.

Exposure

-

c.

Relaxation

-

d.

Activation

-

e.

Other

-

a.

-

16.

For which treatment goals do you use therapeutic VR?*

-

a.

Improve physical mobility

-

b.

Improve stability

-

c.

Improve strength

-

d.

Decrease pain

-

e.

Improve stamina

-

f.

Improve coordination

-

g.

Other

-

a.

-

17.

Which type of hardware do you use for therapeutic VR?*

-

a.

VR headset

-

b.

Nintendo Wii

-

c.

Xbox Kinect

-

d.

Other

-

a.

-

18.

Which type of VR headset do you use for therapeutic VR?*

-

a.

Oculus Go

-

b.

Oculus Quest

-

c.

Oculus Rift (S)

-

d.

Samsung Gear

-

e.

HTC Vive

-

f.

Valve Index

-

g.

Vive Force

-

h.

Pico G2

-

i.

Pico Neo 3

-

j.

Other

-

a.

-

19.

Which type of software do you use for therapeutic VR?*

-

a.

Reducept

-

b.

SyncVR Fit

-

c.

VRelax

-

d.

Corpus VR (InMotion)

-

e.

VRendle

-

f.

Kana

-

g.

SyncVR Relax & Distract

-

h.

Not applicable

-

i.

Other

-

a.

-

20.

Did you use therapeutic VR in the past?

-

a.

Yes

-

b.

No

-

a.

-

21.

Why did you stop using therapeutic VR?*

-

a.

Costs

-

b.

Unsatisfied with results

-

c.

Negative experiences patients

-

d.

Negative experiences physiotherapist

-

e.

Other

-

a.

-

22.

Would you reconsider using therapeutic VR?

-

a.

Yes

-

b.

No

-

a.

-

23.

Why do you not use therapeutic VR?*

-

a.

Costs

-

b.

I do not treat suitable patients

-

c.

I never informed myself

-

d.

Other

-

a.

-

24.

For which conditions would you like to use therapeutic VR?*

-

a.

Musculoskeletal conditions

-

b.

Medically unexplained physical symptoms

-

c.

Heart, arterial or lung conditions

-

d.

Neurological conditions

-

e.

Geriatric conditions

-

f.

Oncology

-

g.

Paediatric conditions

-

h.

Other

-

a.

-

25.

For which possible working mechanism(s) would you like to use therapeutic VR?*

-

a.

Education

-

b.

Exposure

-

c.

Relaxation

-

d.

Activation

-

e.

Other

-

a.

-

26.

For which treatment goals would you like to use therapeutic VR?*

-

a.

Improve physical mobility

-

b.

Improve stability

-

c.

Improve strength

-

d.

Decrease pain

-

e.

Improve stamina

-

f.

Improve coordination

-

g.

Other

-

a.

-

27.

Why do you not use therapeutic VR?*

-

a.

Costs

-

b.

I do not treat suitable patients

-

c.

I never informed myself

-

a.

*more than one option possible.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Slatman, S., Staal, J.B., van Goor, H. et al. Limited use of virtual reality in primary care physiotherapy for patients with chronic pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 25, 168 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-024-07285-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-024-07285-5