Abstract

Background

Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is an uncommon mesenchymal neoplasm, which infrequently metastasizes to pancreas and thigh. Clinical presentation and imaging findings of metastatic broad ligament LMS are often nonspecific. Complete excision plays an important role in treatment of patients with localized LMS.

Case presentation

Here, we report a case of a 33-year-old woman with recurrent broad ligament LMS metastasizing to pancreas and thigh. Previously, she was diagnosed with broad ligament LMS and underwent hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The disease-free interval was 2.5 years until metastases were found. Computerized tomography (CT) of abdomen and thighs, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of thighs and whole-body 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography - computed tomography (PET-CT) performed, revealed pancreatic and thigh metastasis. Ultrasonography-guided biopsy and histological examinations confirmed LMS at both the sites. Pancreatic metastasis was completely resected first. Then the patient underwent surgical resection of thigh metastasis when both chemotherapy and radiotherapy failed. She recovered well and remained free of disease recurrence in the 2 years follow-up.

Conclusions

Though imaging lacks specificity, it is a valuable asset in assessing the burden of disease and characterizing lesions while histological examination with immunohistochemistry is helpful for the diagnosis of LMS. Complete surgical resection of all metastatic sites where-ever feasible should be strongly considered in a treated case of broad ligament LMS with a durable disease-free interval.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is a subtype of soft tissue sarcoma. It is a very uncommon mesenchymal neoplasm with an incidence < 1/100000/year [1]. LMS usually arises from uterus, retroperitoneum, abdomen, large blood vessels, extremities and other soft tissues [2, 3]. Molecular mechanisms underlying its pathogenesis are not clear and early diagnosis and treatment are difficult. Management of LMS requires a multidisciplinary team [4]. Surgical resection is the cornerstone treatment of patients with localized LMS [5]. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy may not show benefit in all cases. Patients with metastases have a dismal prognosis, and the common metastatic sites of LMS are lung and liver [5]. It infrequently metastasizes to pancreas and thigh. After taking symptomatology, co-morbidities, disease-free interval and morbidity of surgery into account, surgical resection of all resectable metastases should be strongly considered where ever feasible [3].

We encountered a case of recurrent LMS of broad ligament of uterus with pancreatic and right thigh metastasis which were successfully treated by surgery. We report this case and discuss the characteristics, diagnosis and management of it, hoping it could provide some hints and inspirations for diagnosis and treatment of metastatic LMS.

Case presentation

A 33-year-old woman with no family history of cancer presented to a local hospital in November 2014 with a palpable mass in hypogastric region. Transvaginal ultrasonography showed a 12 × 8 cm irregular hypoechoic mass with spot blood flow signals and clear boundary on left rear part of the uterus. She was diagnosed with uterine leiomyoma, and underwent an open myomectomy. Pathologic examination revealed a broad ligament LMS, and immunohistochemical analyses showed positivity for SMA and a Ki 67 level of 30%. Subsequently hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy were performed. No tumor cells were detected in sections taken from tubes, ovaries and omentum. She recovered well and then discharged from the hospital.

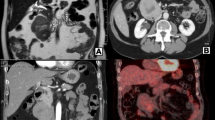

In November 2017, she was referred to our hospital for a mass in the right thigh. On physical examination, a firm mass measuring 10 cm in diameter with tenderness was felt on the back of right thigh, and there were not any positive abdominal findings. Laboratory findings including serum amylase, serum lipase and serum tumor markers (CA19–9 and CEA) were all within normal reference ranges. CT scan of thighs showed a low-density mass with delayed enhancement in the back of right thigh (Fig. 1), and MRI of thighs showed long T1 and long T2 signals on plain scan and high signals on fat suppression imaging. A diagnosis of LMS was established on ultrasonography-guided core needle biopsy, and immunohistochemical study showed positive staining for SMA, Vimentin, Desmin and H-Caldesmon, and negative staining for S-100, CD117, DOG-1 and CD34. To evaluate the overall condition of the patient, a whole-body 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) was performed, which revealed one hypermetabolic lesion on the right thigh and another on the tail of pancreas. Abdominal CT scan showed a 22 mm * 23 mm rounded low-density mass on the tail of pancreas with heterogeneous enhancement in arterial phase (Fig. 2).

A group of experts including surgeons, oncologists, radiologists and pathologists met to provide Multi-Disciplinary Treatments. The surgical team included experienced general and orthopaedic surgeons. Resectability of the two leisons was evaluated by the surgical team of the multidisciplinary team. Neoadjuvant therapy was administered as the tumor was deemed to be borderline resectable with concerns to its proximity to neurovascular bundle. Therefore, we first performed a distal pancreatectomy. The cross-section of the en bloc resected tumor was a whitish fish-liking mass with complete capsule (Fig. 3). The frozen pathological examination supported the diagnosis of an LMS with necrosis, mild atypia, and 17-18 mitosis per 10 high power fields (HPF) (Fig. 4). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for SMA, desmin, h-caldesmon, Ki67 (positive rate 30%), and negative for S-100, CD117, dog-1, CD34.The tumor in the thigh received external-beam radiotherapy (25Gy given in 10 fractions on week days) and chemotherapy (Lobaplatin 50 mg/m2 intravenously daily) for 3 weeks, to which the tumor showed no response. Therefore, the tumor was resected completely with a negative margin. Postoperative pathologic examination was consistent with the former ultrasonography-guided biopsy and frozen pathologic examination of pancreatic tumor. The patient was discharged 5 days after the operation, and free of disease recurrence in the 2 years follow-up.

Histological and immunohistological features of metastatic LMS lesion of pancreas. a hematoxylin and eosin staining showed that cells were spindle, with necrosis, mild atypia, and mitotic figures b-d Immunohistochemistry revealed smooth muscle differentiation. Just like most LMSs, tumor cells showed positive staining for Desmin, H-Caldesmon and SMA. B Desmin, C H-Caldesmon, D SMA

Discussion and conclusions

LMS metastasis to the pancreas is uncommon, and there are few reports. A literature review of LMS metastasis to the pancreas is presented in Table 1 [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

A retrospective study of 13 patients with metastatic pancreatic LMS showed that the median interval between diagnosis of metastases and primary LMS was 24 moths (range, 1–77 moths), and all patients were associated with metastases to other organs [14]. In this case, pancreatic and thigh metastasis were found 3 years after resection of the broad ligament LMS, showing a long interval between the treatment of primary LMS and the appearance of pancreatic metastasis. When there is a pancreatic metastasis, clinicians should be alerted to metastases in other organs. Metastatic pancreatic LMS has no specificity in clinical and image findings, so it is difficult to make an exact diagnosis preoperatively. In contrast-enhanced CT scan, most of metastatic pancreatic LMSs are hypovascular [14], which need to be carefully differentiated from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. In this case, the pancreatic lesion showed heterogeneous enhancement that was lower than the surrounding normal pancreas in arterial phase, and the same enhancement degree with the surrounding tissue in venous phase. Unlike primary pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, metastatic pancreatic LMS has a clear boundary and no manifestations such as dilation of pancreatic bile duct and atrophy of pancreas. These signs are helpful for differentiation. It is interesting to note that the lesion in the thigh showed delayed enhancement, which was different from the enhancement mode of the pancreatic lesion. PET-CT scan can detect and localize metastases. Given that metastatic pancreatic LMS is often accompanied by metastasis to other organs, PET-CT is necessary to estimate the burden of the tumor.

Core needle biopsy is of great value for diagnosis, although inadequate sampling may lead to false negative result. At present, pathological diagnosis of LMS mainly depends on cell morphology. LMS cells are significantly different from smooth muscle cells, characterized by spindle shaped cells arranged in clusters, with rich eosinophilic cytoplasm and hyperchromatic enlongated nucleus [5]. Most LMSs are positive for smooth muscle actin, desmin, and h-caldesmon [3, 5], which are advantageous to differential diagnosis.

Considering neither non-invasive imaging nor pathological examinations can lead to accurate and specific diagnosis of LMS, researchers are eager to find a diagnostic and therapeutic method at molecular level. A study applicating circulating miRNAs as uterine LMS biomarkers found that combination of mir-1246 and mir-191-5p reached a diagnostic rate of 97% [15]. Xiangqian Guo et al. [2] identified 3 LMS molecular subtypes associated with distinct clinical outcomes, making a good exploration of individualized and comprehensive therapy of LMS. Subtype I is most closely similar to smooth muscle differentiation and predicts a favorable outcome. In contrast, subtype II shows no significant smooth muscle differentiation and is associated with unfavourable prognosis. Subtype III shows a preference for uterus.

Some high-frequency gene mutations may act as oncogenes in tumorigenesis and progression of LMS, such as TP53, Rb, ATRX, med12, and PTEN et al. [16, 17]. Mutations of AKT1 (protein kinase b-alpha) and PTEN indicate that PI3K-Akt-mTOR signal pathway play a vital oncogenetic role in LMS [18]. It has been demonstrated that rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTOR, has a certain effect in LMS mice model [19]. In addition, Cantharidin and protease inhibitor (MG-132) also can effectively inhibit viability of LMS cells in vitro [20].

Treatment of metastatic LMS involves a multi-strategy in stepwise management, such as surgery, systemic treatment and radiotherapy [4]. Qian et al. [21] analyzed data of 239 patients with metastatic extremity LMS, and found that surgery plus chemotherapy improved survival of these patients. However, in this case, radiotherapy and chemotherapy all failed. Complete surgical resection was performed with R0 margin status considering the prolonged disease-free interval, feasible resectability of the two isolated lesions, young age and good surgical tolerability of the patient. Finally, clinical benefit with long disease-free survival was achieved by R0 resection (negative margins). It has already been proved that resection of metastatic soft tissue sarcomas in the lung and liver could bring survival benefits [22]. In accordance with NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology for soft tissue sarcoma (version 2, 2018, [23], complete surgical resection of isolated and resectable metastases should be considered in treatment of recurrent broad ligament LMS with a durable disease-free interval.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- CA-199:

-

Carbohydrate antigen 19–9

- CEA:

-

Carcino-embryonic antigen

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- LMS:

-

Leiomyosarcoma

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PET-CT:

-

Positron emission tomography - computed tomography

- SMA:

-

Smooth muscle actin

References

Casali PG, Abecassis N, Aro HT, Bauer S, Biagini R, Bielack S, et al. Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO-EURACAN Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(Suppl 4):iv51–67.

Guo X, Jo VY, Mills AM, Zhu SX, Lee CH, Espinosa I, et al. Clinically relevant molecular subtypes in Leiomyosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(15):3501–11.

George S, Serrano C, Hensley ML, Ray-Coquard I. Soft tissue and uterine Leiomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(2):144–50.

Dangoor A, Seddon B, Gerrand C, Grimer R, Whelan J, Judson I. UK guidelines for the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2016;6:20.

Serrano C, George S. Leiomyosarcoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27(5):957–74.

Alonso Gomez J, Arjona Sanchez A, Martinez Cecilia D, Diaz Nieto R, Roldan de la Rua J, Valverde Martinez A, et al. Uterine leiomyosarcoma metastasis to the pancreas: report of a case and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Cancer 2012;43(2):361–363.

Dima SO, Bacalbasa N, Eftimie MA, Popescu I. Pancreatic metastases originating from uterine leiomyosarcoma: a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:405.

Hernandez S, Martin-Fernandez J, Lasa I, Busteros I, Garcia-Moreno F. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for metastasis of uterine leiomyosarcoma to the pancreas. Clin Transl Oncol. 2010;12(9):643–5.

Iwamoto I, Fujino T, Higashi Y, Tsuji T, Nakamura N, Komokata T, et al. Metastasis of uterine leiomyosarcoma to the pancreas. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2005;31(6):531–4.

Koh YS, Chul J, Cho CK, Kim HJ. Pancreatic metastasis of leiomyosarcoma in the right thigh: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(7):1135–7.

Ogura T, Masuda D, Kurisu Y, Miyamoto Y, Hayashi M, Imoto A, et al. Multiple metastatic leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas: a first case report and review of the literature. Intern Med. 2013;52(5):561–6.

Ozturk S, Unver M, Ozturk BK, Bozbiyik O, Erol V, Kebabci E, et al. Isolated metastasis of uterine leiomyosarcoma to the pancreas: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5(7):350–3.

Sweeney JT, Crabtree DK, Yassin R, Somogyi L. Metastatic uterine leiomyosarcoma involving the pancreas diagnosed by EUS with fine-needle aspiration. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56(4):596–7.

Suh CH, Keraliya A, Shinagare AB, Kim KW, Ramaiya NH, Tirumani SH. Multidetector computed tomography features of pancreatic metastases from leiomyosarcoma: experience at a tertiary cancer center. World J Radiol. 2016;8(3):316–21.

Yokoi A, Matsuzaki J, Yamamoto Y, Tate K, Yoneoka Y, Shimizu H, et al. Serum microRNA profile enables preoperative diagnosis of uterine leiomyosarcoma. Cancer Sci. 2019;110(12):3718–26.

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Electronic address edsc, Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive and integrated genomic characterization of adult soft tissue sarcomas. Cell. 2017;171(4):950–65 e28.

Ravegnini G, Marino-Enriquez A, Slater J, Eilers G, Wang Y, Zhu M, et al. MED12 mutations in leiomyosarcoma and extrauterine leiomyoma. Mod Pathol. 2013;26(5):743–9.

Rao U, Schoedel KE, Petrosko P, Sakai N, LaFramboise W. Genetic variants and copy number changes in soft tissue leiomyosarcoma detected by targeted amplicon sequencing. J Clin Pathol. 2019;72(12):810–6.

Hernando E, Charytonowicz E, Dudas ME, Menendez S, Matushansky I, Mills J, et al. The AKT-mTOR pathway plays a critical role in the development of leiomyosarcomas. Nat Med. 2007;13(6):748–53.

Edris B, Fletcher JA, West RB, van de Rijn M, Beck AH. Comparative gene expression profiling of benign and malignant lesions reveals candidate therapeutic compounds for leiomyosarcoma. Sarcoma. 2012;2012:805614.

Qian SJ, Wu JQ, Wang Z, Zhang B. Surgery plus chemotherapy improves survival of patients with extremity soft tissue leiomyosarcoma and metastasis at presentation. J Cancer. 2019;10(10):2169–75.

Reddy S, Wolfgang CL. The role of surgery in the management of isolated metastases to the pancreas. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(3):287–93.

von Mehren M, Randall RL, Benjamin RS, Boles S, Bui MM, Ganjoo KN, et al. Soft tissue sarcoma, version 2.2018, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2018;16(5):536–63.

Acknowledgements

I thank all the authors for help on the experiment.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XT and XY collected the clinical data and wrote the paper. JW, HLS and ZYS designed the study and revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee and Institutional Review Board of Tianjin First Central Hospital, Tianjin, China. The patient provided informed consent for publication of this case.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and associated images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, X., Yan, X., Wu, J. et al. Recurrent broad ligament leiomyosarcoma with pancreatic and thigh metastasis: a case report. BMC Surg 20, 143 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-020-00804-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-020-00804-w