Abstract

Background

Non-institutionalised older adults is the majority of older adults in Hong Kong. The study aimed to examine erosive tooth wear (ETW) and its association with dental conditions and oral hygiene habits among non-institutionalised older adults in Hong Kong.

Methods

This cross-sectional study recruited dentate adults aged 60 or above from nine elderly daycare centres in the five main districts of Hong Kong. The study consists of a questionnaire survey and a clinical examination. A researcher used a questionnaire to collected the participants’ demographic information, oral hygiene habits such as toothbrushing habits and dental visit behaviour. A calibrated examiner performed an oral examination in the daycare elderly centre to assess the ETW using basic erosive wear (BEWE) criteria. Oral hygiene was recorded using visible plaque index. Prosthetic status was recorded using the World Health Organization criteria. Logistic regression was used to examine the correlation between ETW and the dental conditions and oral hygiene habits.

Results

This study recruited 433 dentate adults and 333 adults were female (77%). Their age ranged from 60 to 99 years and their mean age was 74 years (SD = 7). They all had ETW (BEWE > 0). Over half of them (57%) had BEWE score of 3, indicating severe ETW. Analysis showed increasing age (OR = 1.030, p = 0.029) and older adults with untreated dental caries had higher odds (OR = 1.822, p = 0.002) of presenting severe ETW. No other associations were found between the ETW and the factors studied.

Conclusion

Hong Kong non-institutionalised older adults aged 60 or above had ETW and more than half of them had severe ETW. Increasing age and having untreated dental caries were associated with severe ETW.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The ageing of the population is a global challenge. The United Nations estimated the number of older adults worldwide will double in 2050 [1]. Hong Kong is also facing the problem. With the increased life expectancy of the residents and the declining birth rate [2, 3], the demographic structure of the population of Hong Kong has shifted with an enlarged proportion of older adults [2, 3]. According to the Census and Statistics Department report in 2022, there were 2.2 million residents aged 60 years or over, which consists of 30% of the 7.5 million Hong Kong population [3]. The number is expected to reach 2.58 million by 2069 [3].

Population ageing has a significant impact on the health care system. It leads to an increased demand for healthcare services, higher healthcare costs, and a shortage of healthcare professionals and long-term care facilities [2, 4]. It places a significant burden on healthcare systems and public finances [2, 4]. It is essential to develop strategies to address the impact of ageing on the healthcare system, which requires a deep understanding of the population. Therefore, epidemiological information on the health status of the population should be obtained to develop long-term plans and oral health policies [5].

Oral diseases have a detrimental impact on both the oral and general health of older adults, significantly compromising their quality of life [6, 7]. Good oral health is essential for the ability to taste, chew, and swallow, making it crucial for the overall well-being of older individuals [6, 8, 9]. Oral diseases can cause pain and anxiety, hinder chewing and eating abilities, impede nutritional intake, and pose a threat to the general health of older adults [4, 6, 7].

However, oral disease is prevalent and affects a significant proportion of older adults [10]. The prevalence of oral diseases affecting dental hard tissue is on the rise among older adults [7,8,9,10]. As the population’s lifespan increases, dental hard tissue in the oral cavity is required to function for longer periods, making it more susceptible to diseases [11]. Erosive tooth wear (ETW) is one of the prevalent dental hard tissue diseases affecting older adults [12].

Dental erosion refers to the dissolution of tooth surfaces due to chemical processes from non-bacterial acids [13]. ETW involves the loss of softened tooth surfaces caused by mechanical forces [11, 13]. For instance, wearing dental prosthesis may increase the risk of ETW. The static and slide friction forces from denture base and clasp of the removable partial denture may wear the contact area of the tooth [14]. The frequency of placing and removing the denture from the mouth may also affect the progress of ETW [15]. Moreover, fixed prostheses may increase the risk of ETW on antagonist teeth [16]. Severe ETW can result in the loss of tooth structure, poor aesthetics, and diminished chewing ability [17, 18]. Moreover, severe ETW is challenging to treat and can negatively impact oral health-related quality of life [4, 12]. The prevalence of ETW in children and adults is reported to range from 7.2 to 95.0% in the literature [18, 19]. Studies have been published on the prevalence of ETW in children, adolescents, and young adult populations in Hong Kong, with reported rates ranging from 14.9 to 75% [12, 17, 19]. Our literature search revealed no data on the ETW among older adults in Hong Kong. However, other studies on the oral health status of the older adult population in Hong Kong focused on institutionalised older adults, especially in the chronic health condition group (5, 16, 20). Therefore, data from non-institutionalised older adults in Hong Kong, which is the majority of older adults [2, 3], is warranted.

Consequently, the objective of this study was to examine ETW and its associations with dental conditions and oral hygiene habits among non-institutionalised older adults aged 60 or above in Hong Kong.

Methods

This cross-sectional observational study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (IRB UW 21–316). This study was conducted in 2021–2023. The report in this study was in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement [20].

Sample size calculation

Sample size calculation was performed by G*Power software Version 3.1 and based on the prevalence report in older adults, which reported 62% of older adults had ETW [21]. Sample size of 412 participants would have 80% power to detect an odds ratio of 1.8 based on 60% of the participants having ETW at the 0.05 significant level while assuming the allocation ratio was equal. Assuming the response rate was 90%, the number of older adults to be invited would be at least 457.

Recruitment of participants

Hong Kong has 11 District Elderly Community Centres (DECCs) with a total of 213 elderly daycare centres, and all Hong Kong older adults aged 60 or above must enrol in DECCs which are organized by the Social Welfare Department. The target population were recruited from 5 DECCs from 9 elderly daycare centres due to the permission of Hong Kong government policy during the COVID-19 outbreak. Five DECCs were as follows, Kowloon City and Yau Tsim Mong Districts, Sham Shui Po District, Yuen Long District, Tsuen Wan and Kwai Tsing Districts, and Tuen Mun District. All eligible participants in each daycare centre were invited to the study through invitation letter. Written informed consent was obtained before the clinical examination. The inclusion criteria included dentate older adults aged 60 or above who were cooperative for intraoral examination. The exclusion criteria were participants aged less than 60, complete edentulism, and older adults who had severe systemic diseases such as poorly controlled diabetes mellitus or hypertension, end-stage renal disease, history of acute myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack [22]. Older adults who fulfilled the eligibility criteria were enrolled in the study.

Questionnaire survey

The questionnaire was designed and validated according to the study model reported by previous studies [11, 23,24,25,26,27]. The questionnaire is shown in Table 1. The questionnaire included questions regarding personal information (age and gender) and oral hygiene habits such as toothbrushing habits and dental visit behaviour. Before the clinical examination, participants were asked to complete the questionnaire on-site. An investigator (D.D.C) checked the completed questionnaire when it was returned.

Clinical examination

The clinical examination was conducted at elderly daycare centres by one of two well-trained examiners using non-invasive and painless methods. The clinical examination followed the basic procedures recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), 2013 [28]. No radiograph examination was conducted during the clinical assessment, and no lifestyle or dietary restrictions were required before or after the oral health survey. Both examiners were trained two weeks before the survey to calibrate the oral health assessment. The intra and inter-examiner calibration between the two examiners exceeded 0.70 by the end of training. One-tenth of the participants at each centre were re-examined to determine the inter-examiner agreement. The duplicated clinical examination was performed at least 30 minutes after the first examination.

The clinical examination was conducted using a disposable dental mirror with an attached intraoral light-emitting diode light and a ball-ended WHO probe [12]. Cotton rolls were used for moisture control during the clinical examination. Data recording was carried out by two trained dental assistants. The oral health assessment of participants encompassed prosthetic status, percentage of visible plaque index (VPI), and ETW status. ETW status was recorded with a BEWE index [29]. After the clinical examination, participants received a document detailing their oral health status. Older adults with dental problems requiring treatment were advised to schedule dental treatment appointments at nearby hospitals.

The prosthetic status was examined for both the upper and lower arches, with six conditions: score 0 = no prostheses, score 1 = one bridge, score 2 = more than one bridge, score 3 = partial denture, score 4 = both bridge and partial denture and score 5 = complete denture.

Oral hygiene status was determined using the Visible Plaque Index (VPI) on the buccal and lingual surfaces of index teeth (tooth number 17/16, 11, 26/27, 36/37, 31, 46/47). The visible plaque was as follows: not presence = score 0, presence = score 1 and missing tooth = score 9. The VPI score was calculated as the ratio of the number of surfaces with plaque to the total number of examined surfaces.

The basic erosive wear examination (BEWE) score included four classifications: score 0 = no erosive tooth wear, score 1 = initial loss of enamel surface, score 2 = distinct defect of hard tissue loss less than 50% of the surface area, score 3 = distinct defect of hard tissue loss more than 50% of the surface area [29]. The highest BEWE score on the tooth surface in each sextant represents the ETW status of the entire sextant [12, 29].

Data analysis

The data were recorded on a charting form specifically designed for oral health examinations of elderly individuals in Hong Kong. The data from the questionnaire and clinical examination were input into Microsoft Excel. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0. Intra and inter-examiner agreement was assessed with Cohen’s kappa coefficient based on tooth level. A chi-square test was performed to analyse the differences in the presence of severe ETW (BEWE = 3) according to the distribution of older adult’s demographic characteristics (age and gender), oral health status (number of remaining teeth and denture prostheses), oral hygiene habits (frequency of perform toothbrushing, types of mechanical oral hygiene aids, untreated dental caries, and dental visit experience). Owing to the asymmetric data distribution of age and VPI (by Shapiro-Wilk test), a non-parametric test; the Mann-Whitney test was performed to investigate the association between severe ETW (binary variable using cut-off value BEWE = 3) and VPI and age variables. All the variables were evaluated using a logistic regression model to determine the risk factors of severe ETW in the participants. A backward stepwise was adopted to remove the variables that were not statistically significant. The final model included only statistically significant variables. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

The flow chart of the recruitment of older adults is displayed in Fig. 1. A total of 660 older adults were invited to join the study. 590 older adults agreed to join and 157 older adults were excluded because they absented the survey, could not complete the questionnaire, and could not meet the inclusion criteria. Thus, 433 older adults from 9 elderly daycare centres were examined. The response rate was 73%. Among the 433 participants, approximately three-quarters of the participants were female (n = 333, 76.90%). The mean age of all participants (± SD) was 74 ± 7 years. The kappa value of inter-examiner agreement for the assessment of BEWE was 0.81. Intra-examiner agreement of two examiners were 0.83 and 0.85.

Prosthetic status

The prosthetic status of the upper and lower arch is shown in Table 2. Approximately half of older adults did not have prostheses. The most common type of upper and lower prostheses was bridge, following by partial denture and complete denture.

Erosive tooth wear status

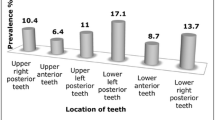

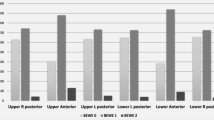

The presence and severity of ETW in Hong Kong older adults, stratified by gender are described in Table 3. BEWE score 0 was detected in none of the participants. ETW (BEWE > 0) presented in 100% of the participants, while severe ETW (BEWE = 3) presented in 56.81% of the participants. The mean age of participants who had severe ETW was 74.3 ± 7.6 years. More than half of males (65%) and females (54.4%) had severe ETW (BEWE = 3). The mean BEWE scores per sextant for males and females were 2.1 ± 0.5 and 2.0 ± 0.5, respectively. The distribution of the severity of ETW in the six sextants is presented in Table 4. The lower anterior teeth had a higher presence and severity of ETW than the other areas.

The bivariate analysis (Table 5) showed that frequency of performing tooth brushing (1/2/≥ 3; p = 0.032), untreated dental caries (yes/no; p = 0.002), and age (p = 0.019) were associated with the presence of severe ETW (BEWE = 3) with statistical significance. However, no statistically significant differences were found in the presence of severe ETW (BEWE = 3) among gender (male/female; p = 0.066), use of toothbrush (yes/no; p = 1.000), use of interdental brush (yes/no; p = 0.290), use of toothpick (yes/no; p = 0.687), tooth condition (< 20 teeth/≥ 20 teeth; p = 0.201), having fixed prostheses (yes/no; p = 0.275), wearing removable prostheses (yes/no; p = 1.000), dental visit experience (less than one year/1–3 years ago/more than 3 years ago; p = 0.264), and VPI (p = 0.455).

The results of the logistic regression are displayed in Table 6. The logistic regression analysis showed that age and having untreated dental caries were statistically associated with the presence of severe ETW, whereas other variables were not statistically significant. The final model examined by backward stepwise binary regression generated the same results as those obtained from the forward stepwise procedure. Participants with increasing age and having untreated dental caries had a higher chance for severe ETW. Increasing age had a significantly higher chance (OR:1.030, 95% C.I: 1.003–1.059) of having severe ETW. Older adults who had untreated dental caries had a higher chance of severe ETW compared to older adults who did not have untreated dental caries (OR: 1.822, 95% C.I: 1.237–2.684).

Discussion

This study was the first epidemiological survey in Hong Kong to report ETW among non-institutionalised older adults aged 60 or above. The population aged 60 and above in Hong Kong is 2.19 million (30% of the population), which is the majority of the Hong Kong population [3]. In addition, the common retirement age of civil servants, non-governmental organisations employees, and government-aid organisations staff in Hong Kong is 60 years old [30]. The data collected from this study provided valuable insights into the presence of ETW in older adults in Hong Kong, which poses significant challenges to their oral health and has long-term implications on their oral and general health [31, 32]. In addition, this study identified independent variables related to oral hygiene habits, which were associated with the presence of severe ETW. These findings may encourage dental professionals to be more vigilant in detecting ETW during regular check-ups for older adults. The data would be helpful for the government and dental professions to plan for community-based preventive measurements for older adults at retirement age. Moreover, it can serve as baseline data for future full-scale population surveys on ETW in older adults in Hong Kong in the future.

The presence of ETW (BEWE > 0) was 100%, while the presence of severe ETW (BEWE = 3) was 56.81% among older adults aged 60 or above. The presence of ETW in the current study was consistent with previous findings in Wuhan City, P.R. China, among Chinese adults aged 50–74 [11]. It is higher than the 40% prevalence observed in Munich, Germany, among older adults aged 65–74 [21, 33] and higher than the 61.9% prevalence in Kibbutz, Israel, among older adults ages 55–60 [34]. The differences in the prevalence of ETW among older adults might be attributed to variations in ETW indices, sample sizes, and geographical factors [19, 21].

In this study, all oral examinations except the ETW assessment followed the guidelines of oral health surveys by the World Health Organization [28]. To date, there is no consensus on the best method for ETW assessment [11, 12]. The basic erosive wear examination (BEWE) is a convenient and time-saving method with high sensitivity and specificity for detecting moderate to severe ETW lesions [11, 35]. This study utilised the BEWE index by Bartlett et al. [29]. The presence of ETW was determined using a BEWE score greater than 0, resulting in 100% of older adults in this study having ETW. However, for the statistical analysis of independent variables related to severe ETW presence, a BEWE score of 3 was used, as no participants were free from tooth wear. This score has high sensitivity and specificity for measuring tooth surface loss in a clinical setting [35], making it a suitable dependent variable for this study [35].

This study found that gender was not statistically associated with the presence of severe BEWE (P = 0.066), which is inconsistent with a previous study that reported males had a higher prevalence of ETW than females [21]. This study found no statistically significant association between severe ETW and frequency of toothbrushing, which is consistent with a previous study [11]. Increased age showed a positive relationship with a higher chance of having severe ETW among older adults, supporting the previous study that mentioned an age-dependent increase in ETW prevalence [11, 21]. Similarly, the pathological finding of ETW lesions progresses with time [12]. Moreover, older adults with untreated dental caries in their mouths had a significantly higher chance (1.822 times) of severe ETW. This finding was consistent with a previous study [36]. The possible reasons can be drawn on this issue that their perception of the need for dental care remains poor, physically unfit, deny dental treatment or more frequent acidic drinks or foods [4, 36].

This study used a closed-ended questionnaire to gather information on dental habits and practices. However, information on dietary habits, such as the frequency and quantity of acidic drinks, beverages or medication daily by older adults, was not collected. The Thematic Household Survey Report of Hong Kong in 2009 reported that 40% of older adults experienced difficulty remembering events that occurred a few minutes prior [4]. Completing complex questionnaires could be challenging and time-consuming for older adults [37]. Moreover, asking them to recall certain details may lead to inaccurate results due to age-related declines in recall ability [37].

This study has some limitations. This cross-sectional observational study was performed during the COVID-19 outbreak when many elderly daycare centres in Hong Kong imposed visiting restrictions. Due to limited resources and time constraints at each centre, we employed a consecutive sampling method instead of a probability sampling method. This approach is considered the best among non-probability sampling methods, as it is simple and efficient, allowing for the inclusion of all potential participants [38]. However, this method may contain a potential risk of selection bias [17]. To minimise the sampling bias, we recruited participants from nine elderly daycare centres in different areas of Hong Kong and ensured no overlap among participants. In addition, according to the results of this study, more than three-quarters of the participants were female. This was in accordance with the previous report that elderly females were more likely to engage in social activities than elderly males [38]. Hence, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution because of these limitations.

Conclusion

All Non-institutionalised older adults in Hong Kong had ETW. Increasing age and having untreated dental caries were associated with severe ETW. No associations were found between the severe ETW, their dental conditions, and oral hygiene habits.

Data availability

The datasets used for this study are available from the first author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ETW:

-

Erosive tooth wear

- BEWE:

-

basic erosive wear

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- OR:

-

Odd ratio

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- DECC:

-

District Elderly Community Centres

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- VPI:

-

Visible plaque index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

United Nations. World Population prospects 2022: Summary of results. Population Division: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2022.

Wong K, Yeung M. Population ageing trend of Hong Kong. Population. 2019;18:64.

Hong Kong Population and Households. Census and Statistics Department Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; 2023.

Chan A, Tamrakar M, Leung K, Jiang C, Lo E, Chu C-H. Oral Health Care of older adults in Hong Kong. Geriatr (Basel). 2021;6(4):97.

Jiang CM, Chu CH, Duangthip D, Ettinger RL, Hugo FN, Kettratad-Pruksapong M, et al. Global perspectives of oral health policies and oral Healthcare schemes for older adult populations. Front oral Health. 2021;2:703526.

Department of Health. Oral health survey 2011. Hong Kong Special Administrative Region: The Government of Hong Kong; 2012.

Liu WY, Chuang YC, Chien CW, Tung TH. Oral health Diseases among the older people: a general health perspective. J Mens Health. 2021;17(1):7–15.

Chan AKY, Tamrakar M, Jiang CM, Lo ECM, Leung KCM, Chu C-H. Common Medical and Dental problems of older adults: a narrative review. Geriatr (Basel). 2021;6(3):76.

Peres MA, Macpherson LMD, Weyant RJ, Daly B, Venturelli R, Mathur MR, et al. Oral Diseases: a global public health challenge. The Lancet. 2019;394(10194):249–60.

World Health Organization. Global oral health status report-Towards universal health coverage for oral health by 2030. 2022.

Wei Z, Du Y, Zhang J, Tai B, Du M, Jiang H. Prevalence and indicators of tooth wear among Chinese adults. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(9):e0162181.

Duangthip D, Chen KJ, Gao SS, Lussi A, Lo ECM, Chu CH. Erosive tooth wear among preschool children in Hong Kong. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2019;29(2):185–92.

Schlueter N, Amaechi Bennett T, Bartlett D, Buzalaf Marília Afonso R, Carvalho Thiago S, Ganss C, et al. Terminology of erosive tooth wear: Consensus Report of a Workshop Organized by the ORCA and the Cariology Research Group of the IADR. Caries Res. 2020;54(1):2–6.

Dąbrowa T, Dobrowolska A, Wieleba W. The role of friction in the mechanism of retaining the partial removable dentures with double crown system. Acta of Bioengineering and Biomechanics. 2013;15(4):43–8.

Carr AB, Brown DT. CHAPTER 4 - biomechanics of removable partial dentures. In: Carr AB, Brown DT, editors. McCracken’s removable partial prosthodontics (Twelfth Edition). Saint Louis: Mosby; 2011. pp. 21–8.

Hmaidouch R, Weigl P. Tooth wear against ceramic crowns in posterior region: a systematic literature review. Int J Oral Sci. 2013;5(4):183–90.

Chu CH, Ng A, Chau A, Lo E. Dental erosion and caries status of Chinese university students. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2015;13(3):237–44.

Salas MMS, Nascimento GG, Huysmans MC, Demarco FF. Estimated prevalence of erosive tooth wear in permanent teeth of children and adolescents: an epidemiological systematic review and meta-regression analysis. J Dent. 2014;43(1):42–50.

Zhang S, Chau AM, Lo E, Chu C-H. Dental caries and erosion status of 12-year-old Hong Kong children. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1–7.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. The Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–7.

Schlueter N, Luka B. Erosive tooth wear - a review on global prevalence and on its prevalence in risk groups. Br Dent J. 2018;224(5):364–70.

Doyle DJ, Hendrix JM, Garmon EH. American society of anesthesiologists classification. 2017.

Sezer B, Giritlioğlu B, Sıddıkoğlu D, Lussi A, Kargül B. Relationship between erosive tooth wear and possible etiological factors among dental students. Clin Oral Investig. 2022;26(5):4229–38.

Wiegand A, Schlueter N. The role of oral Hygiene: does Toothbrushing Harm? Monogr Oral Sci. 2014;25:215–9.

Methuen M, Kangasmaa H, Alaraudanjoki VK, Suominen AL, Anttonen V, Vähänikkilä H, et al. Prevalence of erosive tooth wear and Associated Dietary Factors among a group of Finnish adolescents. Caries Res. 2023;56(5–6):477–87.

Marro F, De Smedt S, Rajasekharan S, Martens L, Bottenberg P, Jacquet W. Associations between obesity, dental caries, erosive tooth wear and periodontal Disease in adolescents: a case–control study. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2021;22(1):99–108.

Schmidlin PR, Schmidlin TM, Gubler A, Brändli S, Attin T. Description of a new laboratory evaluation method of interdental brush abrasion as a clinical hazard. Int J Dent Hyg. 2023.

World Health Organization. Oral health surveys: basic methods. World Health Organization; 2013.

Bartlett D, Ganss C, Lussi A. Basic Erosive wear examination (BEWE): a new scoring system for scientific and clinical needs. Clin Oral Investig. 2008;12(1):65–8.

Arrangements for people close to or at retirement age in selected places [Internet]. 2020 [cited August 9, 2023]. Available from: https://www.legco.gov.hk/research-publications/english/1920rt12-arrangements-for-people-close-to-or-at-retirement-age-in-selected-places-20200630-e.pdf.

Benzian H, Watt R, Makino Y, Stauf N, Varenne B. WHO calls to end the global crisis of oral health. The Lancet. 2022;400(10367):1909–10.

Chawhuaveang DD, Yu OY, Yin IX, Lam WYH, Chu CH. Topical Agents for Nonrestorative Management of Dental Erosion: a narrative review. Healthc (Basel). 2022;10(8):1413.

Jordan RA, Bodechtel C, Hertrampf K, Hoffmann T, Kocher T, Nitschke I, et al. The fifth German oral health study (Fünfte Deutsche Mundgesundheitsstudie, DMS V) - rationale, design, and methods. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14(1):1–12.

Vered Y, Lussi A, Zini A, Gleitman J, Sgan Cohen HD. Dental erosive wear assessment among adolescents and adults utilizing the basic erosive wear examination (BEWE) scoring system. Clin Oral Investig. 2014;18(8):1985–90.

Dixon B, Sharif MO, Ahmed F, Smith AB, Seymour D, Brunton PA. Evaluation of the basic erosive wear examination (BEWE) for use in general dental practice. Br Dent J. 2012;213(3):E4–E.

Mulic A, Tveit AB, Skaare AB. Prevalence and severity of dental erosive wear among a group of Norwegian 18-year-olds. Acta Odontol Scand. 2013;71(3–4):475–81.

Quinn K. Methodological considerations in surveys of older adults: technology matters. Int J Emerg Technol Soc. 2010;8(2):114.

Gao SS, Chen KJ, Duangthip D, Lo ECM, Chu CH. The oral Health Status of Chinese Elderly people with and without Dementia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):1913.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff of the elderly daycare centres in facilitating this survey and older adults for participating in this study. The authors thank Steven Morrell for proofreading this manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the General Research Fund of Research Grants Council of Hong Kong SAR, China (No. 17100820).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DDC: conducted the clinical examination and questionnaire survey, performed data analysis, writing the manuscript. DD: trained and supervised fieldworkers, and performed critical revision of the manuscript. AKYC: performed critical revision of the manuscript. SKYL: contributed to the statistical analysis and data interpretation. CHC: supervised the study and performed critical revision of the manuscript. OYY: trained and supervised fieldworkers, supervised and coordinated field work project, performed critical revision of the manuscript. All authors have read, approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (IRB UW 21–316). The principal investigator is responsible for ensuring the confidentiality of the study documents and protecting the anonymity of all respondents. All participants provided informed consent.

Consent for publication

Participant’s individual person’s data were not contained in this article, and publication consent is not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chawhuaveang, D.D., Duangthip, D., Chan, A.KY. et al. Erosive tooth wear among non-institutionalised older adults in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 24, 53 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-023-03835-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-023-03835-w