Abstract

Background

The objective of this research is to clarify the impact of periodontitis on overall and cardiovascular-related death rates among hypertensive individuals.

Method

A total of 5665 individuals with hypertension were included from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data spanning 2001–2004 and 2009–2014. These individuals were divided into two groups based on the presence or absence of periodontitis and further stratified by the severity of periodontitis. We employed weighted multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression and Kaplan-Meier curves (log-rank test) to evaluate the impact of periodontitis on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Additional analyses, including adjustments for various covariates, subgroups, and sensitivity analyses, were conducted to ensure the robustness and reliability of our results.

Result

Over an average follow-up duration of 10.22 years, there were 1,122 all-cause and 297 cardiovascular deaths. Individuals with periodontitis exhibited an elevated risk of all-cause mortality (HR = 1.33, 95% CI 1.18–1.51; p < 0.0001) and cardiovascular mortality (HR = 1.48, 95% CI 1.15–1.89; p = 0.002). Moreover, we observed a progressive increase in both all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality (p for trend are both lower than 0.001) and correlating with the severity of periodontitis. These associations remained consistent across various subgroup and sensitivity analyses.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest a significant association between periodontitis and increased risks of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among hypertensive individuals. Notably, the severity of periodontitis appears to be a critical factor, with moderate to severe cases exerting a more pronounced impact on all-cause mortality. Additionally, cardiovascular disease mortality significantlly increases in individuals with varying degrees of periodontitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The interplay between chronic diseases and mortality outcomes remains a paramount concern in epidemiological research, particularly as non-communicable diseases (NCDs) continue to rise globally [1, 2]. Among these, hypertension stands out as a predominant cardiovascular risk factor [3], attributed to a significant increase in global morbidity and mortality rates. This condition, affecting an estimated 1.13 billion people worldwide, is a principal driver of adverse health outcomes, notably cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and all-cause mortality [4,5,6]. The multifaceted relationship between hypertension and these outcomes underscores a complex web of pathophysiological mechanisms, including arterial stiffness [7], endothelial dysfunction [8], and a pro-inflammatory state [9], all of which predispose individuals to a heightened risk of cardiovascular events and death [10].

Simultaneously, periodontitis, a pervasive chronic inflammatory condition affecting the supporting structures of the teeth [11], has been increasingly recognized for its potential systemic impact [12]. With a global prevalence that suggests a significant public health challenge [13, 14], periodontitis is not only a leading cause of tooth loss but also implicated in the exacerbation of systemic diseases, including cardiovascular disorders [15] and diabetes [16]. This association is mediated through shared pathophysiological pathways such as systemic inflammation [12, 17] and endothelial dysfunction [18, 19], positing periodontitis as a contributor to the progression of cardiovascular conditions and potentially influencing the disease trajectory in hypertensive individuals.

Despite the established connections between periodontitis and systemic health [20,21,22,23,24,25], the prognosis of periodontitis on individuals with hypertension—a group already at elevated risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [26]—remains underexplored. The relationship between periodontitis and hypertension remains filled with many uncertainties [27]. As demonstrated by this comprehensive review [28], individuals with periodontitis exhibited significantly elevated mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure compared to those without periodontitis, but existing studies lack investigations into the prognosis of hypertensive individuals with periodontitis. This oversight is notable given the high prevalence and significant public health implications of both hypertension [29] and periodontitis [30]. Consequently, our goal is to further explore the potential interactions between periodontitis and hypertension—whether periodontitis has an impact on the prognosis of hypertensive individuals. Bridging this knowledge gap is essential for developing targeted interventions that could mitigate the compounded risk associated with these conditions. We sought to prospectively evaluate a nationally representative cohort of US adults from NHANES—The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, offers a unique opportunity to investigate this association.

Method

Population

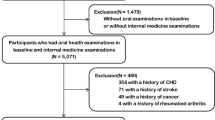

We utilized data from the NHANES cycles 2001–2002, 2003–2004, 2009–2010, 2011–2012, and 2013–2014, as periodontal exams were not conducted between 2005 and 2008. After excluding individuals for missing data on periodontitis status, hypertension diagnosis, other covariates, or follow-up, a total of 5665 eligible individuals were enrolled. The selection process is detailed in Fig. 1.

Assessment of oral examination

Due to variations in periodontal data across different years, we downgraded recent surveys to match the one with less information. We standardized the data by randomly selecting periodontal examination records from one maxillary quadrant and one mandibular quadrant of 2 sites. All clinical examiners were thoroughly trained and calibrated by the survey’s reference examiner. The determination and categorization of periodontitis were based on the utilization of Clinical Attachment Loss (CAL) and Probing Pocket Depth (PPD), following the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in collaboration with the American Academy of Periodontology (CDC–AAP) guidelines.

Definition of hypertension, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality

Hypertension was identified based on the following criteria: a systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg or higher, a diastolic blood pressure of 90 mmHg or higher, self-reported use of anti-hypertensive medications, or a confirmed doctor’s diagnosis.

The assessment of cardiovascular (CVD) and all-cause mortality was conducted using the records from the National Death Index (NDI). Causes of death were classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10).

Definition of covariates

Sociodemographic data and information on comorbidities were collected using standardized questionnaires, tests, and examination procedures. Key variables included:

-

1)

Sociodemographic Characteristics: Age was calculated from birth to the interview date. Gender was self-reported. Ethnicity categories included Mexican American, Other Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Other. Educational levels were classified as less than high school, high school or equivalent, and college graduate or above. Marital status options were married, living with partner, never married, separated, and widowed. Annual household income include: < USD 20,000, USD 20,000–USD 45,000, USD 45,000–USD 75,000, USD 75,000–USD 100,000, > USD 100,000. PIR was used as the indicator of family income and was categorized as below poverty (< 1) and at or above poverty (≥ 1).

-

2)

Lifestyle Factors: Smoking status was categorized as never smokers (those who smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime), current smokers (those who have smoked more than 100 cigarettes) and former smokers (those who smoked > 100 cigarettes and had quit smoking). Drinking status was defined as consuming alcohol 12 or more times per year.

-

3)

Health Conditions:

-

a)

Diabetes: Diagnosis based on a doctor’s confirmation, glycohemoglobin HbA1c level ≥ 6.5%, fasting glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, random blood glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, two-hour oral glucose tolerance test ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, or use of antidiabetic drugs/insulin.

-

b)

Hyperlipidemia: Diagnosed if meeting any criteria of high triglycerides (≥ 150 mg/dL), high total cholesterol (≥ 200 mg/dL), high LDL-C (≥ 130 mg/dL), low HDL-C (< 40 mg/dL in males, < 50 mg/dL in females), or use of lipid-lowering medications.

-

c)

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): Diagnosed if FEV1/FVC ratio < 0.7 post-bronchodilator use, doctor-diagnosed emphysema, or use of specific medications (phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors, mast cell stabilizers, leukotriene modifiers, inhaled corticosteroids) in individuals over 40 years with a smoking history or chronic bronchitis.

-

d)

Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) and Congestive Heart Failure (CHF): Identified based on affirmative responses to specific NHANES questionnaire items.

-

e)

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD): Diagnosed with a Urine Albumin to Creatinine Ratio (UACR) ≥ 30 mg/g and estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) < 60.

-

a)

-

4)

Physical Measurements: Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Levels of white blood cells, platelets, and neutrophils were also recorded.

Statistical analysis

All analyses incorporated sample weights, strata, and primary sampling units, and the significance level was set at 0.05. Continuous variables, assuming normal distribution, were expressed as means with standard errors (SEs), while categorical variables were reported as percentages. The differences between periodontitis and non-periodontitis groups were analyzed using Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and χ² tests for categorical variables. The normality of continuous variables is tested using the Anderson-Darling test.

The Cox proportional hazards model was utilized to evaluate the relationships between periodontitis and both cardiovascular (CVD) mortality and all-cause mortality, ensuring adherence to the model’s proportional hazards assumption. The validity of this assumption was confirmed through the application of Schoenfeld residuals.

Univariate analyses were conducted to ascertain the association of each covariate with the outcomes. Based on these findings, three progressive multivariate models were constructed in two studies. In the study of cardiovascular (CVD) mortality, Model 1 adjusted for gender and age; Model 2 additionally included BMI, drinking status, smoking status, educational levels, annual household income, and the count of neutrophil, platelets; Model 3 further incorporated diagnoses of diabetes, COPD, CHF, CHD, and CKD. As for the study of all-cause mortality, Model 1 included gender and age; Model 2 additionally adjusted for BMI, drinking status, smoking status, educational levels, annual household income, the count of neutrophil, platelets and white blood cells; Model 3 expanded on Model 2 by including the diagnoses of diabetes, COPD, CHF, CHD, and CKD.

The relationship between periodontitis severity and mortality was evaluated by using a linear test (P-trend analysis). Stratified analyses were performed based on several factors, including gender, age, alcohol consumption, smoking status, diabetes status, educational level, and the presence of specific comorbidities like COPD, CHF, CHD, and CKD. Benjamini-Hochberg method was performed in our subgroup analysis. To evaluate the significance of interaction effects, we employed the likelihood ratio method using R.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the robustness of the results. To reduce reverse causality bias, individuals who experienced CVD-related or all-cause deaths within the first two years of follow-up were excluded. The impact of periodontitis on CVD and all-cause mortality risk in hypertensive populations was further assessed using Kaplan-Meier curves and the log-rank test.

Result

Demographic characteristics of individuals

Our study encompassed 5665 individuals, with demographic details presented in Table 1. Upon comparison, individuals with periodontitis differed significantly from those without in several aspects. Individuals with periodontitis were generally older, male. They were also predominantly and had a lower representation of non-Hispanic white. Additionally, a smaller percentage were married. In terms of health conditions, the prevalence of diabetes, COPD, CHD, CKD, and CHF was higher in the periodontitis group. The same trend was observed for individuals with elevated levels of white blood cells and neutrophil. However, platelet counts are different. The percentage of non-drinkers and fomer and current smokers was also higher in the periodontitis group.

Association between Periodontitis and CVD mortality in hypertensive individuals

The relationship between periodontitis and CVD mortality in hypertensive individuals was rigorously analyzed using weighted Cox proportional hazards regression, as depicted in Fig. 2. Covariates that were statistically significant in the univariate analysis were subsequently incorporated into the multivariate models, detailed in Additional File 1: Table S1. Following the adjustment for these covariates, it was observed that hypertensive individuals with periodontitis experienced a higher rate of CVD mortality across all models. Specifically, in Model 1, the HR was 1.78 (95% CI: 1.39–2.26), in Model 2, the HR was 1.58 (95% CI: 1.23–2.03), and in Model 3, the HR was 1.48 (95% CI: 1.15–1.89). Additionally, there was a clear positive association between the severity of periodontitis and CVD mortality in Model 1 (HRs ranging from 1.14 to 2.24), which was consistent in Model 2 (HRs ranging from 1.10 to 1.99) and Model 3 (HRs ranging from 1.13 to 1.92). A significant increasing trend in mortality was noted with the severity of periodontitis (P-trend < 0.05) across all models. This trend was further corroborated by the Kaplan–Meier survival curve analysis, which demonstrated similar findings (log-rank test, P < 0.0001) as shown in Additional File 4: Figure S1.

Graphical representation depicting the relationship between periodontitis and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality in hypertensive individuals. Abbreviations used include HR (hazard ratio), CI (confidence interval), and CVD. The figure shows survey-weighted HRs with 95% confidence intervals and corresponding p-values. Model 1 adjusts for gender (male or female) and age (< 60 or ≥ 60 years). Model 2 includes adjustments from Model 1 plus BMI, drinking status, educational levels, smoking status, annual household income, and the count of neutrophil, platets. Model 3 builds upon Model 2, adding adjustments for diagnoses of diabetes, COPD, CHF, CHD, and CKD

Association between periodontitis and all-cause mortality in individuals with hypertension

In terms of all-cause mortality (Fig. 3), the occurrence of periodontitis significantly elevated the all-cause mortality in hypertension individuals (Model 1, HR = 1.61, 95% CI 1.42–1.82; Model 2, HR = 1.42,95%CI 1.25–1.61; Model 3, HR = 1.33, 95%CI 1.18–1.51). Additionally, an increased rate of all-cause mortality was observed in individuals with moderate and severe periodontitis in Model 1 (HRs ranging from 1.14 to 1.65), Model 2 (HRs ranging from 1.10 to 1.45), and Model 3 (HRs ranging from 1.13 to 1.35). The P value for the trend test was less than 0.05 across all models, indicating that the severity of periodontitis has a considerable impact on all-cause mortality. The Kaplan–Meier survival curve presented comparable findings (log-rank test, P < 0.0001) as shown in Additional File 5: Figure S2.

Illustration of the relationship between periodontitis and all-cause mortality in hypertensive individuals. Model 1 was adjusted for gender (male or female) and age (< 60 or ≥ 60 years). Model 2 included Model 1 plus adjustments for BMI, alcohol consumption status, education level, smoking status, annual household income, the count of neutrophil, platets and white blood cells. Model 3 builds on Model 2 by adding adjustments for the diagnosis of diabetes, COPD, CHF, CHD, and CKD.

Subgroup analyses

To further understand the influence of various covariates on the relationship between periodontitis and mortality outcomes, subgroup analyses were conducted. These analyses, stratified by a range of covariates, uniformly demonstrated that periodontitis is linked to an increased risk of both cardiovascular (CVD) and all-cause mortality in hypertensive individuals. This was evidenced by the fact that nearly all Hazard Ratios (HRs) were greater than 1, as detailed in Table 2 for CVD mortality and Table 3 for all-cause mortality. Notably, the subgroup analysis highlighted the robustness of the correlation between periodontitis and heightened risk of CVD mortality. This relationship was observed across most subgroups (p for interaction > 0.05), except annual household income, that means CVD mortality did not interact with these covariates. Furthermore, CVD mortality increased with the severity of periodontitis with a significant trend (p for trend < 0.05) in most subgroups. Interestingly, we observed that periodontitis has minimal impact on CVD mortality in individuals with CHD, CHF. Consequently, we conducted an analysis of non-CVD causes of mortality, and the results are presented in Additional File 2: Table S2.

Regarding all-cause mortality, as the severity of periodontitis increased, all-cause mortality increased in most subgroups (p for trend < 0.05). Additional, important factors such as age, the presence of chronic kidney disease (CKD), coronary heart disease (CHD), and diabetes, exhibited significant interactions with the outcomes (p for interaction < 0.05). This finding suggests that these specific covariates might differentially influence the link between periodontitis and all-cause mortality in hypertensive individuals.

Sensitivity analyses

To evaluate the robustness of our study’s conclusions, we performed two detailed sensitivity analyses, as outlined in Additional File 3: Table S3. By demonstrating stability in the face of these rigorous tests, our study’s findings are further substantiated, adding to the growing body of evidence on the impact of periodontitis on cardiovascular health and mortality in hypertensive populations.

Discussion

This large cohort study, involving 5665 hypertensive individuals, revealed the effect of periodontitis on CVD and all-cause mortality in individuals with hypertension. It is the first to report an association between periodontitis and mortality in an adequate, representative sample among US individuals with hypertension. Moreover, this is the first study to establish the prognostic value of periodontitis in adults with hypertension. That is, people with periodontitis had a 48% higher risk of CVD mortality than people without periodontitis, while all-cause mortality was 33% higher, showing a significant mortality association between periodontitis and people with hypertension. To reduce the potential for reverse causation bias, we make two sensitivity analyses by excluding individuals who had experienced either cardiovascular disease (CVD)-related or all-cause deaths within the initial two years of the follow-up period. The outcomes of these sensitivity analyses were in line with our primary findings, demonstrating the robustness of our study’s conclusions.

At present, with the increasing number of individuals with periodontitis and hypertension, the relationship between them has been widely discussed in many literatures. [27, 28, 31, 32]. Additionally, a study even concluded that hypertensive individuals are more prone to periodontal infections [33]. However, there remains a relative dearth of studies specifically examining the impact of periodontitis on mortality in hypertensive populations. This study aims to further explore the potential interactions between periodontitis and hypertension, thereby contributing to a broader understanding of how these conditions may interact and impact mortality. Our study delved into a nationally representative sample of US adults with hypertension, contributing to the broader understanding of these correlations. This study concluded that compared to their counterparts without periodontitis, hypertensive individuals with periodontitis exhibited increased rates of CVD and all-cause mortality. Our approach incorporated comprehensive covariate adjustments, stratified analyses, and sensitivity analyses to bolster the reliability and robustness of our results.

In our subgroup analysis, almost all HRs showed a correlation between periodontitis and mortality in individuals with hypertension (HRs > 1). Additionally, our study found an association between various degrees of periodontitis and increased CVD and all-cause mortality in hypertensive individuals. This association was particularly pronounced in those with moderate and severe periodontitis. A noteworthy observation is that age, presence of CKD, CHD and diabetes had significant interactions on the effect of periodontitis on all-cause mortality, while annual household income significantly interacts with its effect on cardiovascular mortality. Surprisingly, our study revealed that periodontitis has a modest impact on the cardiovascular mortality of hypertensive individuals with CHD and CHF. Subsequently, we conducted an analysis of non-cardiovascular mortality in these individuals and found that periodontitis had no significant impact on non-cardiovascular mortality in CHD individuals, but had a significant effect on the CHF group. Perhaps because, in individuals with coronary heart disease (CHD) is likely the dominant health risk factor, whether for CVD-related or non-CVD-related deaths. This means that the health status and mortality risk of these individuals are primarily determined by CHD, with periodontal disease having a relatively smaller impact. As for individuals with chronic heart failure, the impact of periodontitis on CVD mortality is minimal, likely because their baseline CVD risk is already very high, limiting the relative contribution of periodontal disease to cardiovascular disease mortality. While the significant effect of periodontal disease on non-CVD-related deaths may be due to the poorer overall health of individuals with heart failure, making them more vulnerable to the negative effects of periodontal disease.

The mechanisms underlying the relationship between periodontitis and the long-term prognosis of hypertensive individuals are multifaceted and complex. Comprehensive understanding of these mechanisms is crucial for assessing their impact on overall health outcomes. Firstly, the microbiological mechanism deserves emphasis. It involves periodontal pathogens from subgingival biofilms invading blood vessels, spreading to distant tissues, promoting plaque formation, and consequently leading to atherosclerosis [34]. This process underscores the direct impact of oral pathogens on cardiovascular health. Another critical aspect is the inflammatory and immunological mechanisms. Periodontitis can elevate serum levels of pro-inflammatory mediators, matrix metalloproteinases, and nitric oxide. These changes can influence systemic inflammation, which is further exacerbated by alterations in lipid profiles and thrombotic and hemostatic markers [35, 36]. Previous research has demonstrated that inflammation plays a significant role in the pathophysiology of CVD in individuals with hypertension [37,38,39], impacting both the onset and progression of the disease. Therefore, the systemic inflammation caused by periodontitis may contribute to increased mortality in hypertensive individuals. The relationship between oral and cardiovascular health is further highlighted by studies showing that effective management of periodontal disease can reduce the incidence of CVD [40, 41]. This evidence underscores the importance of oral healthcare not just for dental well-being but also for its potential impact on overall cardiovascular health and mortality in individuals with hypertension.

In conclusion, our study establishes a significant association between periodontitis and both cardiovascular disease (CVD) and all-cause mortality in individuals with hypertension. These findings underscore the importance of good periodontal health, not only as a key aspect of oral hygiene but also as a crucial factor in reducing the risk of mortality for adults with hypertension. This highlights the need for integrated healthcare approaches that consider oral health as an integral part of managing hypertension and its associated risks.

Limitations

It is important to acknowledge certain limitations in our study. Firstly, the observational nature of the study design precludes the establishment of causality. Secondly, the reliance on self-reported data for covariates at baseline may lead to reduced accuracy and does not account for changes over time. Lastly, mortality data were obtained by linking to the National Death Index records through probabilistic matching, rather than through direct longitudinal follow-up of individuals. These limitations suggest that while our findings are indicative, they should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

Our study reveals that periodontitis, a chronic inflammatory condition affecting the gums and supporting structures of the teeth, is significantly associated with CVD and all-cause mortality in hypertensive individuals. Notably, there is an observable increase in CVD and all-cause mortality in these individuals as the severity of periodontitis intensifies. Furthermore, moderate to severe periodontitis appears to heighten the risk of CVD and all-cause mortality. These findings underscore the importance of diligent oral health care and effective management of periodontitis, particularly in hypertensive individuals. Proper oral healthcare may offer a viable approach to reducing cardiovascular events and improving long-term health outcomes in this population.

Data availability

The data used in this study are from a public database at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm, which can be accessed by everyone through the links provided in the paper. Data analysis was performed using the statistical packages R (http://www.R-project.org).

Abbreviations

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular Disease

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- NCHS:

-

National Center for Health Statistics

- CAL:

-

Clinical Attachment Loss

- CDC–AAP:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in partnership with the American Academy of Periodontology

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- COPD:

-

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- CHD:

-

Coronary Heart Disease

- CHF:

-

Congestive Heart Failure

- CKD:

-

Chronic Kidney Disease

- WBC:

-

White Blood Cells

- NeuT:

-

Neutrophil

- HR:

-

Hazard Ratio

- SE:

-

Stand Error

References

Bennett JE, Stevens GA, Mathers CD, et al. NCD countdown 2030: worldwide trends in non-communicable disease mortality and progress towards sustainable development goal target 3.4. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1072–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31992-5.

Hunter DJ, Reddy KS. Noncommunicable diseases. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1336–43. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1109345.

McCarthy CP, Natarajan P. Systolic blood pressure and Cardiovascular Risk: straightening the evidence. Hypertension. 2023;80(3):577–9. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.123.20788.

Mancia G, Rosei EA, Azizi M et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Published online 2018.

Unger T, Borghi C, Charchar F, et al. 2020 International Society of Hypertension global hypertension practice guidelines. J Hypertens. 2020;38(6):982–1004. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000002453.

Muntner P, Carey RM, Gidding S, et al. Potential US Population Impact of the 2017 ACC/AHA high blood pressure Guideline. Circulation. 2018;137(2):109–18. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032582.

Boutouyrie P, Chowienczyk P, Humphrey JD, Mitchell GF. Arterial stiffness and Cardiovascular Risk in Hypertension. Circ Res. 2021;128(7):864–86. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.318061.

Ferro CJ, Webb DJ. Endothelial Dysfunction and Hypertension.

Guzik TJ, Nosalski R, Maffia P, Drummond GR. Immune and inflammatory mechanisms in hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol Published Online January. 2024;3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-023-00964-1.

Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2020 update: a Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(9). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757.

Kinane DF, Stathopoulou PG, Papapanou PN. Periodontal diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2017;3(1):17038. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.38.

Genco RJ, Sanz M. Clinical and public health implications of periodontal and systemic diseases: An overview. Periodontol 2000. 2020;83(1):7–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12344

Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray CJL, Marcenes W. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990–2010: a systematic review and Meta-regression. J Dent Res. 2014;93(11):1045–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034514552491.

Larvin H, Kang J, Aggarwal VR, Pavitt S, Wu J. Risk of incident cardiovascular disease in people with periodontal disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2021;7(1):109–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/cre2.336.

Tonetti MS, Van TE. Periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: consensus report of the Joint EFP/ AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and systemic diseases. Published online 2013.

Ilc C. Diabetes and periodontal diseases: consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and systemic diseases. Published online 2013.

Wang GP. Defining functional signatures of dysbiosis in periodontitis progression. Genome Med. 2015;7(1):40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-015-0165-z.

Tonetti MS. Periodontitis and risk for atherosclerosis: an update on intervention trials. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36(s10):15–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01417.x.

Tonetti MS, Nibali L, Parkar M et al. Treatment of Periodontitis and endothelial function. N Engl J Med. Published online 2007.

Romandini M, Baima G, Antonoglou G, Bueno J, Figuero E, Sanz M. Periodontitis, Edentulism, and risk of mortality: a systematic review with Meta-analyses. J Dent Res. 2021;100(1):37–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034520952401.

Kosho MXF, Verhelst ARE, Teeuw WJ, Gerdes VEA, Loos BG. Cardiovascular risk assessment in periodontitis patients and controls using the European systematic COronary risk evaluation (SCORE) model. A pilot study. Front Physiol. 2023;13:1072215. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.1072215.

De Souza CM, Braosi APR, Luczyszyn SM, et al. Association among Oral Health Parameters, periodontitis, and its treatment and mortality in patients undergoing hemodialysis. J Periodontol. 2014;85(6). https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2013.130427.

Tan L, Liu J, Liu Z. Association between periodontitis and the prevalence and prognosis of prediabetes: a population-based study. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):484. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-04340-y.

Sung C, Lin F, Huang R, Periodontitis, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection, and gastrointestinal tract cancer mortality. J Clin Periodontol. 2022;49(3):210–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13590.

Ladegaard Grønkjær L, Holmstrup P, Schou S, Jepsen P, Vilstrup H. Severe periodontitis and higher cirrhosis mortality. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(1):73–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050640617715846.

Oparil S, Acelajado MC, Bakris GL, et al. Hypertension. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2018;4(1):18014. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2018.14.

Martin-Cabezas R. Association between periodontitis and arterial hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2016;180(0).

Muñoz Aguilera E, Suvan J, Buti J, et al. Periodontitis is associated with hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116(1):28–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvz201.

Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of Population-Based studies from 90 countries. Circulation. 2016;134(6):441–50. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018912.

Eke PI, Thornton-Evans GO, Wei L, Borgnakke WS, Dye BA, Genco RJ. Periodontitis in US adults. J Am Dent Assoc. 2018;149(7):576–e5886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2018.04.023.

Czesnikiewicz-Guzik M, Osmenda G, Siedlinski M, et al. Causal association between periodontitis and hypertension: evidence from mendelian randomization and a randomized controlled trial of non-surgical periodontal therapy. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(42):3459–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz646.

Tsioufis C. Periodontitis and blood pressure: the concept of dental hypertension. Published online 2011.

Higashi Y, Goto C, Jitsuiki D et al. Periodontal infection is Associated with endothelial dysfunction in healthy subjects and hypertensive patients.

Herrera D, Molina A, Buhlin K, Klinge B. Periodontal diseases and association with atherosclerotic disease. Genco R, ed. Periodontol 2000. 2020;83(1):66–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12302

Schenkein HA, Papapanou PN, Genco R, Sanz M. Mechanisms underlying the association between periodontitis and atherosclerotic disease. Periodontol 2000. 2020;83(1):90–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12304.

Zardawi F, Gul S, Abdulkareem A, Sha A, Yates J. Association between Periodontal Disease and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular diseases: revisited. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;7:625579. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2020.625579.

Barrows IR, Ramezani A, Raj DS. Inflammation, immunity, and oxidative stress in hypertension—partners in crime? Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019;26(2):122–30. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2019.03.001.

Bartoloni E, Alunno A, Valentini V, et al. Role of inflammatory diseases in Hypertension. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2017;24(4):353–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40292-017-0214-3.

Zhang Z, Zhao L, Zhou X, Meng X, Zhou X. Role of inflammation, immunity, and oxidative stress in hypertension: new insights and potential therapeutic targets. Front Immunol. 2023;13:1098725. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1098725.

Kim NH, Lee GY, Park SK, Kim YJ, Lee MY, Kim CB. Provision of oral hygiene services as a potential method for preventing periodontal disease and control hypertension and diabetes in a community health centre in Korea. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26(3):e378–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12535.

Etta I, Kambham S, Girigosavi KB, Panjiyar BK. Mouth-Heart connection: a systematic review on the impact of Periodontal Disease on Cardiovascular Health. Cureus Published Online Oct. 2023;6. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.46585.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the staff and individuals in NHANES 2001–2004 and 2009–2014 for their contribution to the donation, collection, and sharing of data.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, No. 82200466 to Z.Y.Wang, No. 81770382 to H.T.Yuan), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province of China (ZR2022QH296 to Z.Y.Wang, ZR2023MH141 to H.T.Yuan), Academic promotion program of Shandong First Medical University (2021QL021 to Z.Y.Wang), the Research Incubation Funding of Shandong Provincial Hospital (2021FY043 to Z.Y.Wang), the Taishan Scholar Project of Shandong Province of China (tsqn202306377 to Z.Y.Wang).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design: Z.Y.W. and J.R.L. Analysis and interpretation of data: J.R.L., W.C.Y. and P.C.Y. Drafting of article: J.R.L., Y.J.Y., W.C.Y., X.Z., S.F., and J.J.T. Critical revision: H.T.Y. and Z.Y.W. All authors listed have made a substantial contribution to this work. All authors have read and approved the article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm), and the acquisition and analysis of data were consistent with NHANES research requirements.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Yao, Y., Yin, W. et al. Association of periodontitis with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in hypertensive individuals: insights from a NHANES cohort study. BMC Oral Health 24, 950 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04708-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04708-6