Abstract

Background

The number of children who require palliative care has been estimated to be as high as 21 million globally. Delivering effective children’s palliative care (CPC) services requires accurate population-level information on current and future CPC need, but quantifying need is hampered by challenges in defining the population in need, and by limited available data. The objective of this paper is to summarise how population-level CPC need is defined, and quantified, in the literature.

Methods

Scoping review performed in line with Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for scoping reviews and PRISMA-ScR guidelines. Six online databases (CINAHL, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Medline, PsycINFO, and Web of Science), and grey literature, were searched. Inclusion criteria: literature published in English; 2008–2023 (Oct); including children aged 0–19 years; focused on defining and/or quantifying population-level need for palliative care.

Results

Three thousand five hundred seventy-eight titles and abstracts initially reviewed, of which, 176 full-text studies were assessed for eligibility. Overall, 51 met the inclusion criteria for this scoping review. No universal agreement identified on how CPC need was defined in population-level policy and planning discussions. In practice, four key definitions of CPC need were found to be commonly applied in quantifying population-level need: (1) ACT/RCPCH (Association for Children with Life-Threatening or Terminal Conditions and their Families, and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health) groups; (2) The ‘Directory’ of Life-Limiting Conditions; (3) ‘List of Life-Limiting Conditions’; and (4) ‘Complex Chronic Conditions’. In most cases, variations in data availability drove the methods used to quantify population-level CPC need and only a small proportion of articles incorporated measures of complexity of CPC need.

Conclusion

Overall, greater consistency in how CPC need is defined for policy and planning at a population-level is important, but with sufficient flexibility to allow for regional variations in epidemiology, demographics, and service availability. Improvements in routine data collection of a wide range of care complexity factors could facilitate estimation of population-level CPC need and ensure greater alignment with how need for CPC is defined at the individual-level in the clinical setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Children’s palliative care (CPC) is defined as “an active and total approach to care, from the point of diagnosis or recognition throughout the child’s life, death and beyond.” ([1]: pg.9) CPC has been described as a ‘thread’ that runs through children’s lives, often alongside other treatments, focusing on enhancing quality of life for children and supporting their families, including management of distressing symptoms, provision of short breaks, and care through death and bereavement [1]. There are distinct levels of CPC including the delivery of a palliative approach by all healthcare providers, general palliative care delivered by specialists of a given disease with training in palliative care, and specialist CPC delivered by experts in CPC [2]. There are important differences between adult and children’s palliative care [3] involving very different timescales: CPC (ideally) begins when illness is diagnosed and may be needed for just a few days, or could extend over many years [4]. The potential benefits of CPC include improvements in symptom control and quality of life for children and their parents [2], potential reductions in hospitalisations, and increases in the likelihood that the preferred place of death is achieved [5].

The number of children (aged 0–19 years) who need palliative care has been estimated to be as high as 21 million globally with the majority (> 97%) of them living in low to middle-income countries [3, 6]. However, internationally, access to CPC lags “far behind” that of adult palliative care services ([3]: pg.16) and there are still many countries where CPC is insufficient or unavailable [3, 4]. Adequate provision of CPC services requires accurate information on the number of children who need palliative care, now and in the future, but quantifying need is hampered by challenges in defining the population in need [3, 7,8,9] and by limited available data [2, 4, 10].

Defining CPC eligibility criteria is complicated because the range of health conditions that could make paediatric patients potentially eligible for palliative care is broad and heterogeneous [9]. In addition, CPC eligibility is determined not just by diagnosis but by different ‘care complexity’ factors that also need to be taken into account, including the extent and nature of clinical, psychological, social, organisational, spiritual and ethical problems faced by the child and family ([9]: pg.2). Moreover, the population of children with palliative care needs is changing due to ongoing advancements in medicine and technology which have simultaneously reduced neonatal and paediatric mortality and increased survival of paediatric patients with increasing health and care needs [4, 9, 11,12,13]. For example, many children with neurological conditions are living longer, with rising use of complex medical technologies (e.g., long-term home ventilation, gastrostomy tubes) [4]. However, context is important here, with much of the work on CPC eligibility being carried out in well-resourced settings [14] where the profile of needs may be different to that in lower and middle-income countries.

Clear CPC eligibility criteria are important in both clinical and organisational/planning settings [9]. In the clinical context, individual-level needs are assessed against referral criteria and a decision is taken on whether or when to refer a child to palliative care, together with decisions on the nature and complexity of the palliative need (e.g., general, specialist) [15, 16]. A recently published scoping review categorised the different types of criteria used in clinical settings to initiate a CPC referral, the most common being disease-related, symptom-related and communication-related criteria [15]. A small selection of screening tools were also identified. Overall, the review highlighted broad variations in CPC referral practices across clinical settings and geographic regions. The authors underlined the need to formally evaluate existing criteria (e.g., robust clinical trials, prospective cohort studies) to establish evidence-based CPC referral practices [15].

In the organisational/planning context, policymakers and service planners focus on how CPC is resourced, organised, and delivered to serve the child population in need of palliative care, and rely on population-level (e.g., global, national, regional) estimates of the total number of eligible children to assist current and future planning [10, 12].

The primary aim of this paper is to examine how population-level CPC need is defined and quantified internationally, using a rapid scoping review of the literature. In keeping with the goals of a scoping review to describe and map the literature in a specific field [17], this review documents the most frequently used definitions of CPC need within a broad range of articles focused on population-level CPC need. This includes international policy statements and standards as well as general/conceptual discussions (Category 1), and applied research estimating population-level CPC need (Category 2). The review also examines and categorises the variations in data and methods used to quantify CPC need.

Methodology

Design/method

This review was performed in line with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews [18]. Scoping review findings are presented following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) recommendations [19]. The study protocol is registered in the Open Science Foundation database [20].

The overall aim was to describe how CPC need is defined, and quantified, in a population-level policy and planning context. Specific review questions included:

-

Category 1 – Defining CPC Need (Policy/Concepts): How is CPC need defined in international policy statements/standards and general CPC conceptual discussions?

-

Category 2 – Defining & Quantifying CPC Need (Applied): Within the applied literature on estimating population-level CPC need, how is CPC need defined in these studies, and what data and methods are used to quantify need?

Search terms

Selection of the search terms and eligibility criteria were guided by the PCC (Population, Concept and Context) framework [18]. A list of potential key words and index terms included standard search terms used in other scoping reviews (Table 1). A research librarian with expertise in systematic and scoping reviews supported the development of the search strategy.

Data sources

The search was undertaken between July and October in 2023. Systematic electronic searches of the following academic databases were conducted: CINAHL, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Medline, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. Searches for grey literature (e.g., reports, conference proceedings and policy documents) were also undertaken. This involved identifying key global leaders in advancing children’s palliative care including the World Health Organization, European Association of Palliative Care, and Together for Short Lives (TfSL, based in the UK, one of the first countries to establish CPC as a distinct speciality) [21, 22]. An initial search of their websites was undertaken with a view to identifying relevant literature. The search was supplemented with citation searches on included studies.

Eligibility criteria

Literature that met the inclusion criteria described in Table 2 were included. A timeframe of 15 + years (2008 to October of 2023) was adopted to capture the different ways of defining and quantifying population-level CPC need that would be of current and practical relevance and to increase the efficiency of the search.

Papers were excluded if they failed to meet the inclusion criteria (e.g., did not directly address the review objectives/wrong context), had insufficient detail on the key concepts, were outside the timeframe, focused on an adult population only or where data on children could not be disaggregated, focused on individual-level need in a clinical setting, where only the abstract was available, or multiple papers reported on findings from the same study in which case, the latest article was included. Final search results were exported into Covidence© which facilitates both the efficient screening of papers and the removal of duplicates. Two independent reviewers (SS) and (TD) examined the titles and abstracts for relevance against the inclusion criteria. Selected publications underwent full-text review for relevance (SS and TD). If a discrepancy was identified, a third reviewer (JB) reviewed the paper alongside the pre-specified inclusion criteria and subsequent agreement to include/exclude was made via consensus. Study quality was not reviewed as per scoping review guidelines [18].

Extraction and analysis

A data extraction tool was customised and piloted based on JBI’s ‘template source of evidence details, characteristics and results extraction instrument’ [18]. Two authors (SS and TD) undertook data extraction, each reviewing all of the 51 included articles, and extracting the relevant information into the data extraction tool. A comparative appraisal of the extracted information was facilitated in Covidence©, ensuring consistent extraction of data. The final data extraction tool included the following study descriptives: author(s), year, setting (country/multi-country/global), study aims, study population (age range), and key findings.

The tool also included key study characteristics of specific relevance for the scoping review:

-

Study focus. Articles were categorised according to the two core review questions, i.e., Category 1 (Defining CPC need – policy/concepts) referring to policy statements/standards and general conceptual discussions; and Category 2 (Defining and quantifying CPC need – applied) referring to applied research estimating population-level CPC need.

-

Within the applied literature (Category 2), we extracted key methodological characteristics outlined in standard reporting requirements for applied observational studies (e.g., STROBE, RECORD [23, 24]) including: variables (level of palliative care, definition of CPC need), estimation methods (proportion/number of deaths with CPC needs, prevalence of CPC needs, other) and core data sources (i.e., data, such as mortality, or other clinical data used to define CPC need – note that additional data used as denominators in incidence/prevalence calculations, such as national population data, were not extracted).

Results

Study selection

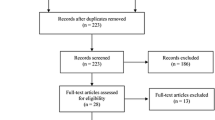

The literature search produced 5,572 records from electronic database searches including an additional 9 documents from grey literature sources (Fig. 1 PRISMA-ScR flowchart). Following the removal of duplicates (n = 1,994), 3,578 titles and abstracts were reviewed and 3,402 were deemed to be irrelevant. 176 full-text studies were assessed for eligibility. Overall, 51 met the inclusion criteria for this scoping review. Reasons for exclusion included studies that were not directly addressing the review objectives (n = 87), insufficient detail on key concepts (n = 11), wrong context (n = 8), unable to source at this time (n = 7), adult population only (n = 3), unable to disaggregate data for children (n = 3), and study more recently described (n = 6).

Study characteristics

Table 3 presents descriptive information on the study characteristics. Of the 51 included papers, the majority (n = 47, 92%) were published between 2013 and 2023. Thirteen studies adopted a multi-country, European or global perspective [1,2,3,4, 6, 14, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31], 10 studies were conducted in either Canada, the USA, or South America [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], 22 studies were undertaken in Europe, of which 14 were UK-based [7, 8, 11, 12, 42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51], and other European countries included Belgium, France, Germany, Ireland, and Italy [9, 52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. Six papers focused on population cohorts in Asia (China, Malaysia, South Korea), Australia, and Africa (Uganda, South Africa) [10, 21, 59,60,61,62].

Of the 51 included papers, 13 articles defined or discussed population-level need for CPC from an international policy, planning, or conceptual discussion perspective (category 1). Thirty-eight articles were applied studies, defining CPC need as well as describing the data and methods used to quantify population-level need for CPC (category 2).

The majority of articles focused on children and young people (n = 37). A small number of articles focused on the perinatal/neonatal population (n = 5). In this paper, the term ‘child’ refers to infants, children and young people unless otherwise specified.

The extracted material from each article (i.e., study descriptives, study focus, applied methodological characteristics, etc.) is presented in Table 4.

Category (1) defining CPC need - policy/concepts

The review included 13 international policy statements/standards and general conceptual discussions on CPC need, of which two referred to both adults and children [6, 26], 11 focused specifically on children [1,2,3,4, 9, 14, 27, 29, 35, 36, 39].

Policy statements/standards

The ‘Global Atlas of Palliative Care’ defined need for palliative care for adults and children in terms of the concept of ‘serious health-related suffering’. The concept was introduced by the Lancet Commission on Global Access to Palliative Care and Pain Relief [63] which outlined 20 diagnostic groups and a range of symptoms needing palliative care [6]. A review of standards and norms for palliative care by the European Association of Palliative Care (EAPC) stated that palliative care should be available to all adults and children with life-threatening diseases (not defined) and highlighted concerns about the use of the emerging concept of serious health-related suffering to describe the objectives of palliative care [26].

The five international palliative care standards and policy statements that were focused on children all drew on key concepts outlined in A Guide to Children’s Palliative Care, by the UK-based charity, Together for Short Lives (TfSL) [1]. In the Guide, CPC need was defined in terms of having a life-threatening condition (for which curative treatment may be feasible but may fail) or life-limiting condition (for which there is no reasonable hope of cure). These conditions were categorised into four groups describing disease progression (Table 5). The groups were first proposed by the Association for Children with Life-threatening or Terminal Conditions and their Families, and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (ACT/RCPCH) in the first edition of the Guide in 1997. This review included the 2018 (4th edition) Guide which noted that aside from diagnosis, other factors (e.g., spectrum of disease, severity of disease, complications, needs of the individual child and family) should be accounted for when determining CPC need [1].

The WHO outlined groups of populations and conditions that generate a CPC need [3]. Population groups were defined in terms of disease progression categories which overlap with the ACT/RCPCH groups (Table 5), and condition groups including malignancies, conditions discovered in the perinatal period, injuries, serious infections, genetic conditions, malnutrition, and pain.

The International Standards for Paediatric Palliative Care (Global Overview – PPC Standards 2021, GO-PPaCS) set out general and specific factors in defining CPC need [2]. At the general level, it was agreed that children with life-threatening, life-limiting, or terminal illness may need CPC. Life-threatening/life-limiting were defined as per the TfSL guide and terminal was defined as a condition where death becomes inevitable in children with life-limiting or life-threatening illnesses. Specifically, conditions eligible for CPC were classified into five categories describing disease progression, the first four of which were adopted from the ‘ACT/RCPCH’ groups (Table 5) and the fifth referred to perinatal/neonatal conditions. These standards also stated that diagnosis is not the only important factor and that the complexity of each child and family’s needs are important to consider. The standards further stated that ‘complex chronic conditions’ (CCCs) should also be considered, a concept developed by Feudtner et al. (discussed below) [32]. The need for standardisation of eligibility criteria was emphasised and a list of ‘red flag’ eligibility criteria were described including diagnosis of a life-limiting/life-threatening condition, serious episodes of hospitalisations, use of invasive medical devices, conditions that cause difficulties in pain/symptom management, complex psychosocial and spiritual needs, and difficulties in making significant decisions. The GO-PPaCS were endorsed in the 2022 European Charter on Palliative Care for Children and Young People ([29] pg.2). A recent blueprint for CPC also described CPC need in terms of the ACT/RCPCH groups [27].

Conceptual discussions

Six review papers discussed key CPC concepts including how CPC need is defined [4, 9, 14, 35, 36, 39]. Spicer et al. [36] outlined an agreed set/lexicon of CPC terminology for use in Canada where CPC need was defined in terms of ‘Life-threatening conditions’ [36]. Life-threatening conditions were defined as encompassing life-limiting or life-shortening conditions, and were described in terms of the ACT/RCPCH groups. It was further explained that life-threatening conditions (as per this lexicon) are frequently complex chronic conditions with significant impact on the child/family [36]. Similarly, an overview of core issues in CPC for medical practitioners described CPC need both in terms of complex chronic conditions and the ACT/RCPCH groups [39].

The remaining four of these papers were published within the last 5 years and provide recent perspective on developments in CPC eligibility discussions [4, 9, 35]. Macauley [35] discussed the origins, and drawbacks, of the term ‘life-limiting’, highlighting its disproportionate use in children’s, compared with adults’, palliative care literature. Macauley [35] noted that the term life-limiting could expand the reach of palliative care by encompassing both shortened life and/or burden of disease but pointed out several problems with the term, including its lack of specificity. Jankovic et al. [9] undertook consensus discussions with experts in the field to identify well-defined CPC eligibility criteria that could be implemented in both clinical and organisational/healthcare planning contexts. The authors provided general guidelines for defining incurability in paediatric cancer and non-cancer patients, and outlined other parameters that should be accounted for (i.e., child and family personal and social factors), subsequently cited in the GO-PPaCS [2, 9]. Fraser et al. [4] and Downing et al. [14] discussed advances and challenges in CPC access and research, including challenges associated with defining the eligible population. Fraser et al. [4] highlighted drawbacks of recent approaches that combine adult and children’s palliative care, citing the difference of opinion at the international level about the new definition of palliative care developed by the International Association of Hospice and Palliative Care that draws on the Lancet Commission concept of serious health-related suffering [64].

Category (2) defining & quantifying CPC need – applied

The review included 38 articles undertaking applied research estimating population-level CPC need. The following sections describe the core definitions of population-level CPC need adopted, noting if/where complexity of need was addressed, and the estimation methods and data sources applied in the studies. (Core methodological characteristics of the applied articles are summarised in Additional File 1.)

Definitions of CPC need in applied literature

Three articles focused on developing a detailed list of diagnoses/conditions that would be considered eligible for CPC, on the understanding that proper planning of services requires detailed information on the population of children who need the services, which in turn requires detailed diagnostic criteria [7, 32, 42]. In each case, the list of diagnoses were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD10), although different versions were used [65]. A further 16 papers applied or modified these lists to estimate population-level need for CPC to inform service planning [12, 33, 34, 41, 43, 45,46,47,48,49, 55,56,57,58, 61, 62]. Nine additional papers compared multiple definitions or adopted study specific definitions [8, 21, 30, 40, 44, 50,51,52, 54]. Four papers focused on perinatal/neonatal palliative care [11, 33, 34, 56]. A final eight papers used unclear or miscellaneous definitions to quantify CPC need [10, 25, 28, 31, 38, 53, 59, 60].

-

Specified Lists of Diagnoses

Feudtner et al. [32] developed a list of complex chronic conditions (CCCs) (in ICD10-CM and ICD10-PM codes) which refer to ‘any medical condition that can be reasonably expected to last at least 12 months (unless death intervenes) and to involve either several different organ systems or 1 organ system severely enough to require specialty pediatric care and probably some period of hospitalization in a tertiary care center’) ([32]: pg.2). This was a revision of an earlier list [66] and includes > 1,000 diagnoses in 10 CCC categories (cardiovascular, respiratory, neuromuscular, renal, gastrointestinal, haematologic or immunologic, metabolic, other congenital or genetic, malignancy, and perinatal) and incorporates a ‘domain of complexity’ referring to dependence on medical technology, and a domain for post-transplant related conditions ([32]: pg.3). The authors note that no single classification system is perfect given the multidimensional nature of the needs of children with complex conditions, and recommend that any system should be transparent and adaptable to each research question [32]. Feudtner et al. [32] compared both versions of the CCCs list in hospital datasets and showed that version 2 classified more patients as having CCCs than did version 1 (with some exceptions). One article in this review used the CCCs list to assess the need for end-of-life CPC in Mexico [41], while another article examined the prevalence of CCCs amongst children in hospital in Belgium and the extent to which children with a CCC were being referred for palliative care [57]. In both studies, CCCs were defined as per version 1, which included diagnoses only and did not include the ‘domain of complexity’ as per version 2 [32, 66]. Lindley et al. [33, 34] examined life-limiting illness amongst neonatal deaths, applying (and comparing) both versions of the CCCs list.

Hain et al. 2013 [7] developed a ‘Directory’ of life-limiting conditions by mapping the four ACT/RCPCH groups onto diagnoses (in ICD10 codes) of patients admitted to palliative care services in the UK. The final version of the Directory included 376 diagnostic labels, and the Directory was piloted through an examination of the proportion of deaths with life-limiting conditions in Wales between 2002 and 2007. Similar to Feudtner et al. [32], the authors highlighted the need to update the list as new diagnoses become apparent. Hain et al. [7] also suggested revisiting the underlying ACT/RCPCH groups where additional conditions could potentially be added where palliative care can play an important role (e.g., traffic injuries) [7]. Three studies in this review estimated need for CPC using the Directory to define need including: an examination of CPC need in a German hospital (with additional assessment of complexity of need in terms of higher needs for medical devices, medications, and nursing care) [55]; an estimate of the number of children dying in hospital in Malaysia with palliative care needs (using the Directory as well as expert opinion to identify life-limiting conditions) [61]; an estimate of the regional prevalence of life-limiting conditions among children in Queensland, Australia [62] .

Fraser et al. 2012 [42] developed a list of life-limiting conditions (in ICD10 codes), labelled here as the ‘LLCs List’, combining two sources of information: Hain’s Dictionary and a list of diagnoses for children accepted for care at a UK hospice. The authors used the term life-limiting to encompass life-threatening conditions and both terms were defined from the TfSL Guide [1]. Each diagnosis on the combined list was assessed as to whether most children with the diagnosis were life-limited/life-threatened; and if most subdiagnoses within the ICD10 code were life-limiting/life-threatening. The final list of 777 4-digit ICD10 codes included any diagnosis that fulfilled those two criteria, and all malignant oncology codes. In the same article, Fraser et al. [42] applied the LLCs List (plus the ICD10 code for palliative care to include persons without a firm diagnosis) to estimate the prevalence of life-limiting conditions amongst children in England. In subsequent work, Fraser and colleagues used the LLCs List (or modified versions, such as examining subsets of the list) to examine detailed trends (by time, age, deprivation, ethnicity) in the prevalence of LLCs amongst children in England [12, 46, 49]. Jarvis & Fraser [47] applied a refined version of the LLCs List to estimate the number children with LLCs in England and Scotland, comparing findings from alternative data sources. In a more recent phase of analysis, Fraser and colleagues [43, 45, 48] have explored in more depth how to capture the complexity of need (e.g., clinical instability, medical complexity) within national estimates (Scotland, Wales) of the prevalence of LLCs amongst children. Drawing on the work by Fraser and colleagues, Ling et al. [58] applied estimates of LLC prevalence from England (based on the LLCs List) to Irish population data to estimate need for CPC in Ireland.

-

Multiple definitions

Five applied articles compared alternative definitions of CPC need including the Directory, the LLCs List, and other definitions used in the adult palliative care literature (e.g., rule of thumb type estimates, such as a given % of deaths) [8, 21, 44, 50, 54].

Four of those studies applied alternative population prevalence methods from the literature (some of which captured complexity in terms of symptom prevalence) to local data (e.g., mortality data) to estimate need for palliative care for children, or for adults and children [8, 21, 44, 50]. For example, one article applied both the Directory and the List of LLCs to estimate national prevalence of LLCs in South Korea (categorising the diagnoses according to the CCC classification system).

One study applied alternative estimates of prevalence of need (based on different definitions of CPC need) from the literature to population data to estimate national (Italy) level of CPC need [54]. Most of the prevalence estimates adopted in the study did not take complexity into account (i.e., diagnoses only, or rules-of-thumb), with the exception of one estimate which incorporated estimates of pain prevalence.

-

ACT/RCPCH definitions

Four studies quantified CPC need using the ACT/RCPCH groups to guide the definition of need although detailed lists of diagnoses were not provided [30, 40, 51, 52]. For example, Alotaibi et al. [30] estimated CPC need across 6 countries (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates) defining need in terms of life-threatening illness (categorised by ACT/RCPCH groups, but not listed).

-

Miscellaneous definitions

One article estimated the proportion of deaths with serious health-related suffering (i.e., from the Lancet Commission [63]) to examine global need for palliative care (adults and children), drawing on a list of diagnoses combined with empirical evidence on physical and psychological suffering for different diseases [28]. Two multi-country studies examined the prevalence of a pre-defined list of diseases (based on analysis by the WHO for the 2014 version of the Global Atlas) as well as pain prevalence to estimate the CPC need [25, 67].

Five additional studies quantified CPC need using study-specific definitions, or unclear definitions (i.e., detailed lists of inclusion criteria not provided), of CPC need [10, 38, 53, 59, 60]. Lu et al. [10] estimated the number of children in need of end-of life care at a national level (China). Need for end-of-life palliative care was defined in terms of deaths from any medically-related illness with no additional adjustment for complexity of need. Benini et al. [53] examined the proportion of hospitalisations with life-limiting or life-threatening diagnoses amongst children in Italy (drawing on a list of diagnoses developed in an earlier study by the same authors [68]). Jacinto et al. [59] examined the proportion of hospital admissions (adults and children) with ‘active life-limiting disease’, defined as any disease that is progressive, incurable and likely to be terminal, and thereby designated as appropriate for palliative care referral ([59]: pg.197). Boss et al. [38] examined the proportion of hospital admissions ‘chronically critically ill’ where children’s palliative care could be beneficial, drawing on diagnostic as well as information on prolonged/repeated hospitalisations, technology dependence, and multiorgan dysfunction ([38]: pg.1832). Celiker et al. [60] estimated CPC need within one hospital (Cambodia), defining need in terms of having a chronic, progressive, debilitating, or life-limiting illness drawing on diagnostic and other details on infection and intensive-care use.

-

Defining perinatal/neonatal need for palliative care

Perinatal palliative care has been defined as “[an] approach to health care services that addresses the needs of the fetus [sic] and parents beginning at the time of diagnosis, and extending through the birth, through the death of the infant and, and into the bereavement period” ([69]: pg.367). Three papers examined and highlighted challenges in applying existing CPC diagnostic lists (e.g., CCCs list, the LLCs List) to the perinatal/neonatal population [33, 34, 56]. A fourth paper established a detailed list of 60 + antenatal/postnatal conditions that would be considered eligible for palliative care, consistent with guidelines set out by the British Association of Perinatal Medicine (BAPM) [11]. A fifth paper described the need for neonatal palliative care in terms of ‘neonatal serious illness’, defined as carrying a high risk of short term mortality, may involve prognostic uncertainty, and substantially impacts on the patient’s and family’s life [37].

Data and estimation methods in applied literature

Two broad estimation approaches were identified in the applied articles: an incidence approach, focusing on the proportion or number of deaths with end-of-life care needs, or an approach involving estimation of the prevalence of CPC needs (however defined) over a longer disease trajectory. Measuring prevalence of CPC need requires data on children living with illness such as disease prevalence, hospital admission or other healthcare utilisation data.

The following describes these two approaches as applied in the literature, outlining the methods used and the core data types.

-

Incidence of end-of-life care needs & mortality data

Eight studies relied on mortality data to estimate CPC need. Four studies examined the number of children with end-of-life care needs at a national level (China, England, Malaysia, Mexico, Wales) using national mortality data [7, 10, 44], or hospital inpatient data (deaths only) [41, 61]. Sleeman et al [28] used mortality data to estimate the proportion of global deaths (adults and children) with serious health-related suffering. Two studies examined the proportion of neonatal deaths with life-limiting illness using hospital inpatient data (deaths only) [33, 34].

-

Prevalence approach & mortality data

Three studies combined disease prevalence data and mortality data from the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (US) to estimate prevalence of CPC need [25, 30, 67].

-

Prevalence approach & clinical chart data

Four studies used clinical chart data to estimate the proportion of hospital inpatients with CPC needs (variously defined). Three out of the four examined CPC needs within one ward/hospital [55, 56, 59], and the fourth retrospectively surveyed chart data to estimate prevalence of CPC needs in one region [52]. Two of these studies supplemented clinical chart data with hospital inpatient administrative data [55, 56].

-

Prevalence approach & hospital inpatient data

Six studies examined hospital inpatient administrative data (e.g., demographic details, diagnoses, procedures, length of stay, discharge destination, etc.) to estimate population prevalence of CPC needs [40], or the number/proportion of children in one/multiple hospitals with CPC needs [32, 38, 53, 57, 60]. One of these studies analysed both hospital outpatient and inpatient data to examine CPC needs [40].

-

Prevalence approach & linked datasets

Ten studies used linked datasets to quantify CPC need [12, 42, 43, 45,46,47,48,49,50, 62]. Of these, four studies used linked hospital inpatient and mortality data to quantify national/regional prevalence estimates of CPC need [12, 47, 50, 62], one of which examined alternative data sources and demonstrated that estimating prevalence using death records only underestimates CPC need [47].

Fraser and colleagues linked hospital admission data with geographic and deprivation data to examine national (England) prevalence of CPC need by area and deprivation factors [42, 46, 49]. In three more recent studies of national prevalence of CPC need (Scotland, Wales), Fraser and colleagues linked hospital admission and mortality data with additional data sources (e.g., paediatric intensive care, outpatient, general practice, prescribing data) intending to capture more information about complexity of need [43, 45, 48].

-

Prevalence approach & specific research datasets

Six studies used miscellaneous datasets and methods to quantify CPC need [8, 11, 21, 51, 54, 58]. Kim et al. [21] analysed national health insurance claims data, incorporating inpatient, outpatient, and emergency department utilisation, to estimate the national prevalence of life-limiting conditions in South Korea. Harnden et al. [11] examined the National Neonatal Research database to estimate the proportion of neonatal admissions with palliative care needs in England and Wales. A study by TfSL used a minimum dataset from palliative care providers to examine the prevalence of CPC in specific regions [51]. Three studies applied estimates of CPC prevalence from the literature to population data to estimate national/regional level of CPC need (Ireland, Italy, North Wales) [8, 54, 58].

Discussion

Overview

This rapid scoping review has shown that there is no universal agreement on how CPC need is defined in population-level planning, although there are four key definitions of CPC need that have been commonly applied in quantifying population-level need. To a large extent data availability drives the methods used to estimate population-level CPC need and only a small proportion of articles incorporated measures of complexity of need. The following outlines key lessons from the findings, highlighting important issues to take into account in future work clarifying key concepts and methods when defining and quantifying population-level need for CPC.

Key lessons

No universally agreed definition of CPC need

The findings describe multiple ways of defining population-level CPC need (e.g., broad disease trajectories, lists of life-limiting/life-threatening conditions, lists of complex chronic conditions, serious health-related suffering, active life-limiting disease, chronically critically ill, etc.) highlighting the absence of a universally agreed definition in the literature.

Within policies that focused on CPC only, there was common reference to the ACT/RCPCH disease trajectories [1, 70], although the most recent global standards for CPC (GO-PPaCS [2]) expanded beyond the original four disease groups, adding a fifth relating to perinatal/neonatal conditions. The GO-PPaCS standards also acknowledged the need for greater standardisation in eligibility criteria and highlighted the importance of considering complexity of need. The standards themselves were complex, adopting more than one set of eligibility criteria including the (modified) ACT/RCPCH groups; complex chronic conditions; as well as the ‘red flag’ criteria developed by Jankovic et al. [9]. Challenges in defining need for CPC were also confirmed in the discussion/review literature, citing the inconsistent and varied use of key terms (life-limiting, life-threatening, life-shortening, etc.) as well as challenges due to ongoing changes in the population of children that could benefit from palliative care. The concentration of work to define and quantify need for CPC in higher income countries is also notable in this review. For example, over half of the applied articles in this review were undertaken in the UK and US. Further consideration is needed of regional variations in palliative care needs, particularly in relation to differing disease profiles observed across low-, middle- and high-income countries [3, 6, 14, 30]. Thus, although consistency in defining CPC need is important, future work on defining population-level need for CPC needs to be flexible so as to allow for international variations in epidemiology, demographics and service availability.

Four common definitions of CPC need in applied literature

Despite the overall inconsistency in defining CPC need, the applied work on quantifying CPC need was dominated by a small number of specific definitions. Almost 60% of the applied articles used one of four definitions of CPC need, namely the ACT/RCPCH groups (11%), CCCs (14%), the Directory (11%), and the List of LLCs (24%), and additional articles applied one or more of these definitions where multiple definitions were adopted or compared. Both the Directory and the List of LLCs are conceptually linked with the ACT/RCPCH groups thereby highlighting the prominent place occupied by these disease trajectories in describing the life-limiting/life-threatening conditions considered eligible for CPC. The groups themselves have not changed since they were first published in 1997 [71] but additional groups have been proposed [2, 7, 14]. There is work underway to revise the groups [72] although the focus is on defining need in the clinical setting, in the UK, rather than on population-level planning.

The two most detailed lists, CCCs (> 1000 diagnoses and > 1,600 procedures), and the List of LLCs (777 + diagnoses), together accounted for 38% of the applied articles included in this review. While both were initially developed using mortality data, our results found notable differences in where and how these lists have since been applied (Additional File 1), yet no article included in this review undertook a detailed direct comparison of these two applied definitions of CPC need. Thus, there is scope for further research to compare and contrast these, and other lists (e.g., serious health-related suffering). The proposed analysis could examine the rationale for the application of one list over another or develop a refined/combined list leading to more systematic, internationally comparable methods for defining CPC need.

Data requirements when quantifying CPC need

In the majority of the applied studies, the estimation method was driven by data availability, and 47% of articles cited challenges with data limitations in this field. This is particularly relevant for LMICs where the challenge will be greater in resource-constrained settings. Nearly a third of the applied articles used data on deaths only, which restricted the analytic focus to end-of-life care. This has been acknowledged to be particularly problematic for quantifying palliative care need amongst children (relative to adults), where the trajectory of palliative care needs may extend for several years [50] depending on the child’s condition and circumstances. Relying on mortality data to estimate CPC need risks under-estimating the number of children who could benefit from palliative care [30, 41, 44]. To facilitate proper resourcing, planning and delivery of CPC, analysts need access to population-level data on children living with life-limiting illnesses (however defined) so as to capture needs over the full trajectory of illness and not just at the end of life.

Defining complexity of need – those with and without specified diagnoses

Complexity of need was directly measured in 35% of the applied articles, but with varying degrees of detail. Methods included national estimates of pain or symptom prevalence, small-scale studies of detailed clinical chart data, examination of procedure codes to identify technology dependence (i.e., using the CCCs list), or use of linked datasets including mortality, healthcare utilisation and prescribing data to provide richer information on care needs. Most of these studies focused on examining complexity of needs within a given cohort of children deemed eligible for palliative care based on specified diagnoses. However, fewer studies addressed a second source of complexity, namely the challenge of capturing palliative care eligibility amongst cases where there was no diagnosis, or where the need for palliative care was based not on diagnosis but on a combination of factors such as the care complexity factors as described by Jankovic et al. ([9]: pg.2). Access to richer population-level data on care needs and social and family circumstances (e.g., including parental mental health) is an important challenge for this field to capture both sources of complexity. Future work is needed on conceptualising complexity in children’s palliative care and identifying data that can inform those conceptions.

Need for greater alignment between clinical and planning settings

The need for greater alignment in CPC eligibility criteria between the clinical and organisational/planning settings has also been highlighted in the literature [9, 37]. For example, Guttmann et al. noted that having a research/planning definition of CPC need with no relevance to a clinical context is likely to have “very limited utility’ ([37]: pg.1659). As highlighted in the scoping review by Carney et al. [15], clinical referral practices are varied and thus greater consistency is needed both within, and between the clinical and organisational/planning settings. Carney et al. [15] noted that disease- and symptom-related criteria were the dominant sources of information used in the majority of clinical referral practices in their rapid scoping review, with less focus on child and family psychosocial and emotional support. At the minimum, future work is needed to enhance access to population-level information on symptoms as well as diagnosis to facilitate greater alignment between the two settings.

However, improvements in routine data collection on a wider range of complexity of need factors could greatly assist both individual-level referral practices and population-level planning, and their alignment. As outlined by Noyes et al., data collection for CPC is complicated by the fact that the data need to be of precise and practical use “about service needs that are often subjective and individual” ([8]: pg.2). Thus, it is important for service providers and planners to consider all the evidence, from both individual-level clinical referral practices (as reviewed by Carney et al. [15]), and population-level planning (as reviewed here), on different options for data collection to capture CPC needs.

Level of palliative care not often specified

In more than 50% of the applied articles, it was not clear if the aim was to quantify need for all/some levels of palliative care (i.e., general, specialist, etc.) (see Additional File 1). Greater clarity is needed on the different data requirements for quantifying need for general versus specialist palliative care.

Limitations

This scoping review was restricted to English language articles which limited the size of the review. However, the focus on English gave a reasonable estimate of the scope of the literature in this field particularly given that the UK was one of the first places to develop CPC as a distinct specialty [21, 22]. A protocol for a scoping review focusing on use of administrative data to quantify CPC need in several non-English articles could further supplement the findings in this review [73].

In reviewing the full texts, three types of articles were identified, namely those that directly addressed the scoping review questions on defining or quantifying population-level need for children’s palliative care, articles where a definition of need could be indirectly deduced from the content (e.g., analysis of a sample of patients considered eligible for children’s palliative care) (n = 7) [74,75,76,77,78,79,80], and articles which analysed characteristics of patient samples already in receipt of children’s palliative care (n = 3) [81,82,83]. While we only included the first type of papers in this review, the latter two types of papers could also be examined for insight into how need for children’s palliative care is defined in the general literature.

The quality of articles was not assessed, as is typical for a scoping review. While details on setting, variables, data and estimation methods could be reported for most of the articles in this review, there were some for which the definitions, data, and/or methods were unclear. Future reviews in this field could examine more closely the quality of the methods used to quantify need for CPC.

Conclusions

This review scoped 51 articles including international policies and standards, discussion/review articles, and applied literature to examine how population-level need for CPC is defined and quantified. Overall, greater consistency in how CPC need is defined in population-level planning is important, but with sufficient flexibility to allow for regional variations in epidemiology, demographics, and service availability. Improvements in routine data collection of a wide range of care complexity factors could facilitate estimation of population-level CPC need and ensure greater alignment with how need for CPC is defined at the individual-level in the clinical setting.

Availability of data and materials

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. No additional data available.

Abbreviations

- CPC:

-

Children’s Palliative Care

- LLCs:

-

Life-Limiting Conditions

- CCCs:

-

Complex Chronic Conditions

- ACT/ RCPCH:

-

Association for Children with Life-threatening or Terminal Conditions and their Families, and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health

- TfSL:

-

Together for Short Lives

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Together for Short Lives. A guide to children’s palliative care. Together for Short Lives: Bristol; 2018.

Benini F, Papadatou D, Bernada M, et al. International standards for pediatric palliative care: From IMPaCCT to GO-PPaCS. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63:e529–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.12.031.

World Health Organisation. Integrating palliative care and symptom relief into paediatrics: A WHO guide for health care planners, implementers and managers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Fraser LK, Bluebond-Langner M and Ling J. Advances and challenges in European paediatric palliative care. Med Sci (Basel) 2020;8. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci8020020.

Mitchell S, Morris A, Bennett K, et al. Specialist paediatric palliative care services: what are the benefits? Arch Dis Child. 2017;102:923–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2016-312026.

Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance. Global atlas of palliative care. London: Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance; 2020.

Hain R, Devins M, Hastings R, et al. Paediatric palliative care: Development and pilot study of a 'directory' of life-limiting conditions. BMC Palliative Care 2013;12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-12-43.

Noyes J, Edwards RT, Hastings RP, et al. Evidence-based planning and costing palliative care services for children: Novel multi-method epidemiological and economic exemplar. BMC Palliative Care 2013;12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-12-18.

Jankovic M, De Zen L, Pellegatta F, et al. A consensus conference report on defining the eligibility criteria for pediatric palliative care in Italy. Italian J Pediatrics 2019;45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-019-0681-3.

Lu Q, Xiang ST, Lin KY, et al. Estimation of pediatric end-of-life palliative care needs in China: A secondary analysis of mortality data from the 2017 National Mortality Surveillance System. J Pain Sympt Manage. 2020;59:E5–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.02.019.

Harnden F, Lanoue J, Modi N, et al. Data-driven approach to understanding neonatal palliative care needs in England and Wales: A population-based study 2015–2020. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2022-325157.

Fraser LK, Gibson-Smith D, Jarvis S, et al. Estimating the current and future prevalence of life-limiting conditions in children in England. Palliat Med. 2021;35:1641–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216320975308.

Tosello B, Dany L, Betremieux P, et al. Barriers in referring neonatal patients to perinatal palliative care: A French multicenter survey. PLoS One 2015;10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0126861.

Downing J, Boucher S, Daniels A, et al. Paediatric palliative care in resource-poor countries. Children (Basel) 2018;5. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5020027.

Carney KMB, Goodrich G, Lao AMY, et al. Palliative care referral criteria and application in pediatric illness care: A scoping review. Palliat Med. 2023;37:692–706. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163231163258.

Bergstraesser E, Hain RD and Pereira JL. The development of an instrument that can identify children with palliative care needs: the Paediatric Palliative Screening Scale (PaPaS Scale): A qualitative study approach. BMC Palliative Care 2013;12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-12-20.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, et al. Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols. JBI Evid Synth 2022; 20: 953–968. 2022/02/02. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-21-00242.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E MZ, (ed.). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, JBI, 2020. 2020.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Straus SE. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

Smith S, Delamere T, Sheaf G, et al. Defining and measuring need for children's palliative care: A protocol for a rapid scoping review. Center for Open Science, 2023.

Kim CH, Song IG, Kim MS, et al. Healthcare utilization among children and young people with life-limiting conditions: Exploring palliative care needs using National Health Insurance claims data. Sci Rep. 2020;10:2692. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59499-x.

Harrop E, Edwards C. How and when to refer a child for specialist paediatric palliative care. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2013;98:202–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2012-303325.

Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. The REporting of studies conducted using observational routinely-collected health data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001885. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335:806–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD.

Connor SR, Downing J, Marston J. Estimating the global need for palliative care for children: A cross-sectional analysis. JOURNAL OF PAIN AND SYMPTOM MANAGEMENT. 2017;53:171–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.08.020.

European Assoc Palliative Care, Payne S, Harding A, et al. Revised recommendations on standards and norms for palliative care in Europe from the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC): A Delphi study. Palliat Med. 2022;36:680–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163221074547.

Roland J, Lambert M, Shaw A, et al. The children’s palliative care provider of the future: A blueprint to spark, scale and share innovation. London: Imperial College London; 2022.

Sleeman KE, de Brito M, Etkind S, et al. The escalating global burden of serious health-related suffering: projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups, and health conditions. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e883–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30172-X.

European Association for Palliative Care. European charter on palliative care for children and young people. Vilvoorde: European Association for Palliative Care; 2022.

Alotaibi Q, Dighe M. Assessing the need for pediatric palliative care in the six Arab Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Palliat Med Rep. 2023;4:36–40. https://doi.org/10.1089/pmr.2022.0037.

Connor S, Sisimayi C, Downing J, et al. Assessment of the need for palliative care for children in South Africa. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2014;20:130–4. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2014.20.3.130.

Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, et al. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: Updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-199.

Lindley LC, Cozad MJ, Fortney CA. Pediatric complex chronic conditions: Evaluating two versions of the classification system. West J Nurs Res. 2020;42:454–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945919867266.

Lindley LC, Fortney CA. Pediatric complex chronic conditions: Does the classification system work for infants? Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36:858–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909119838985.

Macauley RC. The limits of “life-limiting.” J Pain Sympt Manage. 2019;57:1176–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.03.010.

Spicer S, Macdonald ME, Davies D, et al. Introducing a lexicon of terms for paediatric palliative care. Paediatr Child Health. 2015;20:155–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/20.3.155.

Guttmann K, Kelley A, Weintraub A, et al. Defining neonatal serious illness. J Palliat Med. 2022;25:1655–60. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2022.0033.

Pediat Chronic Critical I, Boss RD, Falck A, et al. Low prevalence of palliative care and ethics consultations for children with chronic critical illness. Acta Paediatrica. 2018;107:1832–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.14394.

Moody K, Siegel L, Scharbach K, et al. Pediatric palliative care. Prim Care. 2011;38:327-+. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2011.03.011.

Randall V, Cervenka J, Arday D, et al. Prevalence of life-threatening conditions in children. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2011;28:310–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909110391463.

Cardenas-Turanzas M, Tovalin-Ahumada H, Romo CG, et al. Assessing need for palliative care services for children in Mexico. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:162–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2014.0129.

Fraser LK, Miller M, Hain R, et al. Rising national prevalence of life-limiting conditions in children in England. Pediatrics. 2012;129:E923–9. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2846.

Public Health Scotland. Children in Scotland requiring palliative care (ChiSP) 3. Edinburgh: Children’s Hospices Across Scotland; 2020.

Etkind SN, Bone AE, Gomes B, et al. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med. 2017;15:102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0860-2.

Fraser L, Bedendo A and Jarvis S. Children with a life-limiting or life-threatening condition in Wales: Trends in prevalence and complexity Final report May 2023. 2023. NHS Wales National Programme Board for Palliative and End of Life Care.

Fraser LK, Lidstone V, Miller M, et al. Patterns of diagnoses among children and young adults with life-limiting conditions: A secondary analysis of a national dataset. Palliat Med. 2014;28:513–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216314528743.

Jarvis S, Fraser LK. Comparing routine inpatient data and death records as a means of identifying children and young people with life-limiting conditions. Palliat Med. 2018;32:543–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216317728432.

Jarvis S, Parslow RC, Carragher P, et al. How many children and young people with life-limiting conditions are clinically unstable? A national data linkage study. Arch Dis Child. 2017;102:131–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2016-310800.

Norman P, Fraser L. Prevalence of life-limiting conditions in children and young people in England: Time trends by area type. Health Place. 2014;26:171–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.01.002.

Murtagh FEM, Bausewein C, Verne J, et al. How many people need palliative care? A study developing and comparing methods for population-based estimates. Palliat Med. 2014;28:49–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216313489367.

Together for Short Lives. The Big Study for life-limited children and their families: Final research report. Bristol: Together for Short Lives; 2013.

Emilia Romagna Paediat P, Amarri S, Ottaviani A, et al. Children with medical complexity and paediatric palliative care: A retrospective cross-sectional survey of prevalence and needs. Italian J Pediatr 2021;47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-021-01059-8.

Benini F, Trapanotto M, Spizzichino M, et al. Hospitalization in children eligible for palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:711–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2009.0308.

Benini F, Bellentani M, Reali L, et al. An estimation of the number of children requiring pediatric palliative care in Italy. Italian J Pediatr 2021;47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-020-00952-y.

Bösch A, Wager J, Zernikow B, et al. Life-limiting conditions at a university pediatric tertiary care center: A cross-sectional study. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:169–76. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2017.0020.

Garten L, Ohlig S, Metze B, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of neonatal comfort care patients: A single-center, 5-year, retrospective, observational study. Front Pediatr 2018;6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2018.00221.

Friedel M, Gilson A, Bouckenaere D, et al. Access to paediatric palliative care in children and adolescents with complex chronic conditions: A retrospective hospital-based study in Brussels. Belgium BMJ Paediatr Open. 2019;3: e000547. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2019-000547.

Ling J, O’Reilly M, Balfe J, et al. Children with life-limiting conditions: Establishing accurate prevalence figures. Ir Med J. 2015;108:93.

Jacinto A, Masembe V, Tumwesigye NM, et al. The prevalence of life-limiting illness at a Ugandan national referral hospital: A 1-day census of all admitted patients. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2015;5:196–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000631.

Celiker MY, Pagnarith Y, Akao K, et al. Pediatric palliative care initiative in Cambodia. Front Public Health 2017;5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00185.

Khalid F, Chong LA. National pediatric palliative care needs from hospital deaths. Indian J Palliat Care. 2019;25:135–41. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_111_18.

Bowers AP, Chan RJ, Herbert A, et al. Estimating the prevalence of life-limiting conditions in Queensland for children and young people aged 0–21 years using health administration data. Aust Health Rev. 2020;44:630–6. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH19170.

Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Krakauer EL, et al. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief-an imperative of universal health coverage: the Lancet Commission report. Lancet. 2018;391:1391–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32513-8.

Radbruch L, De Lima L, Knaul F, et al. Redefining Palliative Care-A New Consensus-Based Definition. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:754–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.027.

World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992.

Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980–1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106:205–9.

Connor S and Sisimayi C. Assessment of the need for palliative care for children. Three country report: South Africa, Kenya and Zimbabwe. 2013. UNICEF and the International Children’s Palliative Care Network.

Benini F, Ferrante A, Buzzone S, et al. Childhood deaths in Italy. Eur J Palliat Care. 2008;15:77–81.

Mendes J, Wool J, Wool C. Ethical considerations in perinatal palliative care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2017;46:367–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2017.01.011.

ACT. A guide to the development of children’s palliative care services. Bristol: ACT; 2009.

ACT and RCPCH. A Guide to the Development of Children’s Palliative Care Services. Bristol & London: Association for Children with Life-threatening or Terminal Conditions and their Families and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health; 1997.

TfSL. Together for Short Lives: Definitions event. 2024.

Ramos-Guerrero J, Dusssel V, Domandé D, et al. Who needs pediatric palliative care (PPC)? A scoping review of classification models to identify children who would benefit from PPC. Open Science Framework: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DKJTZ, 2023.

Berry JG, Hall M, Cohen E, et al. Ways to identify children with medical complexity and the importance of why. J Pediatr. 2015;167:229–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.04.068.

Chang E, MacLeod R, Drake R. Characteristics influencing location of death for children with life-limiting illness. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:419–24. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2012-301893.

Chavoshi N, Miller T, Siden H. Resource utilization among individuals dying of pediatric life-threatening diseases. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:1210–4. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.0110.

DeCourcey DD, Silverman M, Oladunjoye A, et al. Patterns of care at the end of life for children and young adults with life-threatening complex chronic conditions. J Pediatr. 2018;193:196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.09.078.

Knapp CA, Madden VL, Wang H, et al. Effect of a pediatric palliative care program on nurses’ referral preferences. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:1131–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2009.0146.

Lindley LC, Edwards SL. Geographic variation in California pediatric hospice care for children and adolescents: 2007–2010. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35:15–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909116678380.

Rossfeld ZM, Miller R, Tumin D, et al. Implications of pediatric palliative consultation for intensive care unit stay. J Palliat Med. 2019;22:790–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2018.0292.

Hoell JI, Weber H, Warfsmann J, et al. Facing the large variety of life-limiting conditions in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2019;178:1893–902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-019-03467-9.

Taylor LK, Miller M, Joffe T, et al. Palliative care in Yorkshire, UK 1987–2008: Survival and mortality in a hospice. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:89–93. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2009.158774.

Stutz M, Kao RL, Huard L, et al. Associations between pediatric palliative care consultation and end-of-life preparation at an academic medical center: A retrospective EHR analysis. Hosp Pediatr. 2018;8:162–7. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2017-0016.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following ECHPI Project Advice Team members for their valuable oversight of the ECHPI Project: Dr Peter May, Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing, Midwifery & Palliative Care/Cicely Saunders Institute of Palliative Care, King’s College London; Professor Suzanne Guerin, School of Psychology, University College Dublin/Research at LauraLynn; Dr Helen Coughlan, St. Vincent’s University Hospital, Dublin; Ms Paula O’Reilly & Ms Avril Easton, Irish Hospice Foundation; Ms Orla Murphy, PPI Representative; Mr Maurice Dillon, Health Service Executive (HSE); Mr Tyrone Hone, HSE Cork University Hospital; Dr Mary Rabbitte, All Ireland Institute of Hospice & Palliative Care; Dr Fiona McElligott, Children’s Health Ireland at Temple Street Hospital, Dublin; Dr Mary Devins, Children’s Health Ireland at Crumlin; Mr Paul Rowe, Department of Health; Ms Sinead O’Hara, Healthcare Pricing Office, HSE; Dr Cliona McGarvey, National Office of Clinical Audit. The authors would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful feedback and suggestions.

Funding

This project is funded by the Irish Health Research Board [APA-2022–003] and co-funded by the Irish Hospice Foundation and LauraLynn Ireland’s Children’s Hospice. Full title: Improving Children’s Palliative Care in Ireland: using evidence to guide and enhance palliative care for children with life-limiting conditions and their families. Short title: Evidence for Children’s Palliative care in Ireland (ECHPI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS and JB designed and secured Health Research Board funding for the overall ECHPI project. The ECHPI project consists of five individual work packages including this rapid scoping review. SS, JB, and TD developed the search and index terms with support from LF. GS developed the search strategy with contributions from SS and TD. SS and TD examined the titles and abstracts. Selected publications that met the inclusion criteria were reviewed as full-texts. JB was consulted at the full-text stage where any discrepancies occurred. Authors SS and TD drafted the original manuscript. JB, LF and GS suggested/revised the manuscript, which were collated by SS and TD. All authors approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Delamere, T., Balfe, J., Fraser, L.K. et al. Defining and quantifying population-level need for children’s palliative care: findings from a rapid scoping review. BMC Palliat Care 23, 212 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-024-01539-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-024-01539-8