Abstract

Background

The previous effects of acupuncture-related interventions in improving chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) symptoms and quality of life (QoL) remain unclear in terms of pairwise comparisons.

Aims

This systematic review and network meta-analysis aimed to determine the hierarchical effects of acupuncture-related interventions on symptoms, pain, and QoL associated with CIPN in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Methods

Nine electronic databases were searched, including PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, EBSCO, Medline Ovid, Airiti Library, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), China Journal full-text database (CJFD), and Wanfang. Medical subject heading terms and text words were used to search for eligible randomized controlled trials published from database inception to May 2023.

Results

A total of 33 studies involving 2,027 participants were included. Pairwise meta-analysis revealed that acupuncture-related interventions were superior to usual care, medication, or dietary supplements in improving CIPN symptoms, CIPN pain, and QoL. Furthermore, network meta-analysis indicated that acupuncture plus electrical stimulation (acupuncture-E) had the greatest overall effect among the various interventions. The surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) revealed that acupuncture-E ranked the highest in improving CINP symptoms. Acupuncture alone was most effective in reducing CIPN pain, and acupuncture plus moxibustion (acupuncture-M) ranked highest in enhancing QoL.

Conclusion

This finding suggests that acupuncture-related interventions can provide patients with benefits in improving CIPN symptoms, pain, and QoL. In particular, acupuncture-E could be the most effective approach in which the provided evidence offers diverse options for cancer patients and healthcare professionals.

Implication for the profession and/or patient care

These findings provide valuable insights into the potential benefits of acupuncture-related interventions for managing symptoms, pain, and QoL associated with CIPN in patients undergoing chemotherapy. Among the various interventions studied, overall, acupuncture-E had the most significant impact and was effective for a minimum duration of 3 weeks. On the other hand, transcutaneous electrical acupoint/nerve stimulation (TEAS) was identified as a noninvasive and feasible alternative for patients who had concerns about needles or the risk of bleeding. It is recommended that TEAS interventions should be carried out for a longer period, preferably lasting 4 weeks, to achieve optimal outcomes.

Trial registration

The study protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. Registration Number: CRD42022319871.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to cancer treatment guidelines, radical surgery is the main cancer treatment, while chemotherapy and concurrent chemoradiotherapy are used as adjuvant treatments [1]. Chemotherapy, which involves the use of cytotoxic chemicals to eliminate or shrink tumors, enhances survival rates [2]. However, chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) has a high global prevalence rate of 85% [3], and 63% in Taiwan [4]. After chemotherapy, patients may persistently suffer from CIPN for several months to years or even experience irreversible sequelae [5]. The clinical characteristics of CIPN include paresthesia (tingling, burning sensation), hyperalgesia (sensitivity to noxious stimulation), allodynia (pain induced by normal innocuous stimulation), and decreased physical activity [5, 6]. This may cause patients to receive reduced doses with decreased treatment efficacy or withdraw from chemotherapy. Notably, the severity of CIPN symptoms depends on drugs, doses, treatment period, and other comorbidities, such as diabetes, prior exposure to neurotoxic agents, and alcohol exposure [7]. While CIPN does not cause death directly, it causes important distress in the daily life of patients due to sensory and motor disorders and lowers their quality of life (QoL) [8, 9].

Cytostatic groups of antineoplastic agents, especially those containing platinum, taxanes, and vinca alkaloids, induce CIPN through different mechanisms of neurotoxicity, but these remain unclear [6, 10]. Platinum accumulates in the sensory nerve cell bodies and damages the DNA of the dorsal root ganglia, whereas taxane and vincristine inhibit the production of tubulin proteins and damage myelin surrounding neuronal axons, leading to the disruption of axonal transport [11]. CIPN occurs when neurotoxic antineoplastic drugs accumulate and lead to conduction dysfunction in the peripheral nervous system. CIPN symptoms have a common stocking-and-glove distribution, characterized by paranesthesia, dysesthesia, numbness, and tingling of feet and hands, which are associated with neuropathic pain [6]. At the onset of CIPN symptoms, chemotherapy is frequently decreased or stopped, with a possible deleterious impact on the oncological prognosis. Currently, there is no recommended agent for preventing CIPN, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology [6]. As for treating CIPN, available data only point to duloxetine with moderate recommendation, but there is a lack of convincing evidence [12].

Systematic review studies have shown show that cancer patients seek additional help for CIPN, with 25–80% of them using non-pharmacological therapy [13, 14]. Several systematic reviews have defined the benefits of reducing CIPN provided by acupuncture, massage, exercise, and dietary supplements [5]. Acupuncture-related interventions, which have drawn researchers’ attention in recent years, are widely accepted for their ancestral medical culture in the Chinese population and for their safety [15]. Acupuncture is an ancient practice that originated within traditional Chinese medicine, in which needles are inserted into the skin at acupoints throughout the body [16]. According to the principles of traditional Chinese medicine, stimulating acupoints leads to increased blood flow in the capillaries around the needle insertion sites, releases local opioid peptides, alters sympathetic tone, reduces inflammation, and stimulates specific areas of the brain [17]. Several systematic review studies have concluded that CIPN symptoms and pain can be improved by acupuncture [18, 19] and acupuncture combined with electrical stimulation [20, 21]. However, other studies did not support the improvement of symptoms by acupuncture [22, 23]. In addition to symptom management, the importance of evidence-based practice is emphasized for improving QoL in patients with cancer. However, several studies have reported that acupuncture affects QoL [18, 21], while others found no effect [19]. The above studies indicate that the effects of acupuncture-related interventions in improving neuropathy-related symptoms and QoL remain unclear in terms of pairwise comparisons. Therefore, this study systematically reviewed published studies and applied pairwise and network meta-analyses to determine not only the effects but also the hierarchy of acupuncture-related interventions on symptoms, pain, and QoL associated with CIPN in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Methods

Data sources and searches

A systematic review and network meta-analysis (NMA) of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were conducted. This study’s report followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). The study protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42022319871). Nine electronic databases were searched, including PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, EBSCO, Medline Ovid, Airiti Library, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), China Journal full-text database (CJFD), and Wanfang. Medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and text words were used in the search strategy for searching eligible RCTs published from database inception to May 2023. Duplicate studies were removed. When similar studies by the same authors were found, the latest publication or that with high-quality evidence was chosen. Titles and abstracts were screened based on the selection criteria. Subsequently, the full texts of the studies were further reviewed for inclusion in the systematic review, and only complete data were included in the meta-analysis. A form collecting information on participants, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO) was used to compose key research questions. Cancer patients (P) were treated with acupuncture-related interventions (I) compared with usual care, medication, or dietary supplements (C) to determine the effects of acupuncture-related interventions on CIPN symptoms, CIPN pain, and QoL (O).

Inclusion and/or exclusion criteria

Participant types

All RCTs used acupuncture techniques to manage CIPN problems, with no limitation on cancer types, sex, or race of adult patients diagnosed with CIPN. Individuals with peripheral neuropathic symptoms due to other factors such as diabetes mellitus, genetic disease, spinal cord injury, tumor compression, nutritional disorders, and alcoholism were excluded.

Intervention types

In general, acupuncture-related interventions involve various techniques for stimulating acupoints [24]. This study categorized acupuncture-related interventions into acupuncture alone, acupuncture plus electrical stimulation (Acupuncture-E), acupuncture plus moxibustion (Acupuncture-M), and transcutaneous electrical acupoint/nerve stimulation (TEAS).

Comparison types

The comparators used were usual care, medication, and dietary supplements. Usual care was defined as the chemotherapy protocol. The medication referred to medical drugs prescribed for CIPN. Dietary supplements were products with vitamin B taken orally.

Data extraction

The five research team members jointly obtained information from the included studies. Doubts and discrepancies were resolved through discussions. The accuracy of all the included studies was evaluated by the research team.

Assessment of methodological quality of included studies

Each RCT was independently assessed by the same research team. The Cochrane Collaboration’s Assessing Risk of Bias 2.0 tool was used, consisting of six domains: bias risk arising from the randomization process; bias risk due to deviations from the intended interventions; risk of missing outcome data; bias risk in measuring the outcomes; bias risk in selecting the reported results; and overall risk of bias [25]. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Cochrane Review Manager 5.4, CINeMA web application, and STATA version 15 statistical software. Pairwise and network meta-analyses using a random-effects model to pool each treatment was performed to compare the effects of the acupuncture-related interventions and the corresponding control group on the incidence rate of CIPN (risk ratio [RR]), the severity of CIPN pain (mean difference [MD]), and the level of QoL (standardized mean difference [SMD]). CINeMA was also used to perform an NMA through direct and indirect comparisons of the intervention effects. Finally, the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) was generated to determine the intervention hierarchy indicating the percentage of cumulative probability for each intervention to rank best [26].

Additionally, publication bias was qualitatively examined using Egger’s test. Certainty of evidence was evaluated using CINeMA grading the six domains: within-study bias, referring to the impact of risk of bias in the included studies; reporting bias, referring to publication and other reporting bias; indirectness; imprecision; heterogeneity; and incoherence. Results across domains were summarized together with the certainty of evidence according to four levels: very low, low, moderate, and high confidence. To assess the differences between direct and indirect comparisons and investigate the presence of a loop among the interventions, the consistency test using the χ2 test for node-splitting analysis was used. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and the 95% confidence interval (CI) was used.

Results

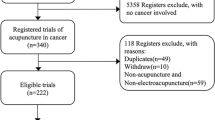

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process. There 2935 studies were identified using the electronic databases and 9 studies of grey literature obtained from other searching. Eventually, 33 and 31 studies were included in the meta-synthesis and meta-analysis, respectively. The characteristics of the included studies on acupuncture-related interventions were reported, involving 2027 patients suffering with CIPN (Table 1) [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59]. The average dropout rate of participants was 4.1%, with 4 RCTs reporting a rate between 13.7% [27, 28] and 17.5% [40, 54]. The age of participants averaged 57.99 years and was similar in the experimental and control groups. The targeted cancer types were colorectal cancer in 23 RCTs, breast cancer in 14 RCTs, lung cancer in 11 RCTs, gastric cancer in 14 RCTs, other cancers in 15 RCTs, and non-reported cancer type in 6 RCTs. Six RCTs studied cancer in stages II and III, 5 RCTs studied cancer in stages IV, 3 RCTs studied cancer in stage I, and 26 RCTs were not reported. The duration of interventions ranged between 2 and 16 weeks, with the majority being 3 weeks (10 RCTs), followed by 2 and 8 weeks (6 RCTs for each duration).

Figure 2 illustrates the overall risk of bias assessment results, indicating that 35% of RCTs were classified as having a low risk of bias, while 45% were classified as having a high risk of bias. The primary concern was related to blinding. Consequently, a subgroup analysis was conducted to evaluate the clarity of the blinding process in these RCTs. Included studies were categorized into a "yes-blind" group if the blinding process was explicitly described and an "unclear-blind" group if it was not. Figures 3, 4, and 5 illustrate the impact of acupuncture-related treatments on CIPN symptoms, pain, and QoL, respectively. The subgroup analysis revealed significant effects on CIPN symptoms (p < 0.001) and pain (p < 0.001). However, the effect on CIPN QoL was significant only in the unclear-blind group (p < 0.001), and not in the yes-blind group (p = 0.35). Additionally, there were no significant differences between the two groups on CIPN symptoms (p = 0.77), pain (p = 0.62), and QoL (p = 0.91).

The degree of confidence in the evidence was obtained using the CINeMA (Appendices 1–3). All included studies were considered with no concerns about reporting bias and incoherence and some concerns about indirectness. The majority of comparisons were graded as moderate to low in CIPN pain and QoL but very low in CIPN symptoms. Additionally, the results from the loop inconsistency models for transitivity were obtained using the STATA (Appendices 4–6). These findings suggested that, overall, there was no substantial inconsistency in the comparisons made within the loop inconsistency models for CIPN symptoms, pain, and QoL. However, out of 13 loops, three exhibited significant inconsistency in CIPN QoL, specifically in comparing TENS and usual care, TENS and supplement, and acupuncture-M and supplement.

Effects of acupuncture-related interventions

Pairwise meta-analysis showed acupuncture-related interventions reduced the incidence of CIPN symptoms, with a significant difference compared to the control group (OR = 4.32, 95% CI = 3.09 to 6.02). Publication bias was not observed in the pooled studies (Egger’s test, p = 0.32). A network plot of the included comparisons is shown in Fig. 6. Table 2 shows the league table that acupuncture-E (OR = 16.56, 95% CI = 4.90 to 55.99; OR = 9.89, 95% CI = 4.18 to 23.40; OR = 15.99, 95% CI = 4.43 to 57.67) and acupuncture-M (OR = 5.16, 95% CI = 1.17 to 22.87; OR = 3.08, 95% CI = 1.11 to 8.57; OR = 4.98, 95% CI = 1.03 to 24.10) were significantly more effective than usual care, medication, and dietary supplements, respectively. Acupuncture (OR = 3.70; 95% CI, 1.50 to 9.12; OR = 3.57, 95% CI = 1.45 to 8.80) were significantly more effective than usual care, and dietary supplements, respectively. Additionally, TEAS was significantly more effective than usual care (OR = 5.77; 95% CI, 1.84 to 18.13). As determined by SUCRA and shown in Fig. 7, acupuncture-E (87.8%) had the highest possibility of being the best intervention on CIPN symptoms.

Network plot for the outcomes of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) symptoms, pain, and quality of life. Note, the size of the nodes corresponds to the number of participants assigned to each treatment; treatments with direct comparisons are linked with a line; its thickness corresponds to the number of trials evaluating the comparison

A pairwise meta-analysis of acupuncture-related interventions for alleviating CIPN pain showed a significant difference compared to the control group (MD = -1.05, 95% CI = -1.44 to -0.67). Publication bias was not observed in the pooled studies (Egger’s test, p = 0.45). As shown in Table 2, acupuncture (MD = -1.18, 95% CI = -2.23 to -0.12; MD = -1.28, 95% CI = -2.34 to -0.21) and acupuncture-E (MD = -1.12, 95% CI = -2.36 to -0.12; MD = -1.22, 95% CI = -2.42 to -0.01) were significantly more effective than usual care and dietary supplements, respectively. Acupuncture (MD = -1.18, 95% CI = -2.29 to -0.07) was significantly more effective than medication. SUCRA ranking revealed acupuncture (47.8%) had the highest likelihood of ranking highest (Fig. 7).

A pairwise meta-analysis of acupuncture-related interventions for improving QoL showed a significant difference (SMD = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.18 to 0.83). Publication bias was not observed in the pooled studies (Egger’s test, p = 0. 44). As shown in Table 2, acupuncture-E (SMD = 1.18, 95% CI = 0.27 to 2.09) was significantly more effective than usual care, acupuncture-E (SMD = 1.65, 95% CI = 0.52 to 2.77), acupuncture-M (SMD = 1.49, 95% CI = 0.43 to 2.55) and acupuncture (SMD = 1.12, 95% CI = 0.08 to 2.16) were significantly more effective than medication. SUCRA ranking revealed acupuncture-M (43.2%) had the highest likelihood of ranking highest (Fig. 7).

Safety of acupuncture-related interventions

Of the 33 RCTs, 14 reported information about adverse events. Minor dizziness, slight ecchymosis, nominal bleeding, swelling, and bruising at acupuncture sites have been reported [27,28,29, 40, 45]. As local hematomas developed, cold compresses were provided and the patient recovered within a few days. Seven RCTs reported no adverse events.

Discussion

The evidence from this study supports the benefits of improving symptoms, pain, and QoL associated with CIPN by using acupuncture-related interventions. These interventions involved a variety of techniques including the use of needles, electrical stimulation, and moxibustion. Overall, acupuncture-E was the most effective among these interventions. Acupuncture alone could be the most effective intervention in decreasing CIPN pain; whereas acupuncture-M might be most effective for improving QoL. TEAS emerged as the second most effective intervention for alleviating CIPN symptoms, following acupuncture-E, which ranked first.

In CIPN patients, the immunological processes and production of neuroinflammation are impaired, leading to conduction dysfunctions in their peripheral nervous system [10]. CIPN refers to symptoms involving paranesthesia, dysesthesia, numbness, tingling, and neuropathic pain [6, 11]. Through the stimulation of specific acupoints, acupuncture leads to the activation of sensory nerve endings and specific nerve fibers with transmission to the brain through nervous pathways. This process results in anti-neuroinflammatory effects on modulation [60, 61] and nerve conduction [62], and stabilizes the concentration of ions inside and outside cells to avoid protein denaturation [63], which prevents and treats neurotoxicity. Pain-related problems are also improved by the release of endorphin, which is secreted from the pituitary gland, into the cerebral spinal fluid and blood to achieve an analgesic effect [64]. Acupuncture-induced analgesia may be mediated by the peripheral afferent Aβ, Aδ, and C nerve fibers. The gate control theory of pain confirms that after stimulation, the large myelinated Aβ fibers are excited by γ-aminobutyric acid interneurons in the spinal cord [65]. Stimuli through acupuncture at specific acupuncture points blocks the pain conduction of the Aδ and C fibers [65].

Similarly to acupuncture, an electric stimulus delivered to acupuncture points activates nerve fibers and produces analgesic effects [66]. A systematic review pointed out that acupuncture-E effectively decreased CIPN pain compared to Vitamin B [21]. One key advantage of electrical stimulation is the enhancement of analgesic action through a consistent and adjustable electric current and power [64]. Acupuncture-E effectively reduced CIPN symptoms in a study in which they improved motor and sensory disorders, especially by contributing to increased sensory nerve conduction velocity [20, 21]. As the nerve conduction velocity in the limbs increased, their functional status improved. This study also supports that the overall effect acupuncture-E and TEAS for managing CIPN symptoms and pain is superior to that of usual care, medication and vitamin B supplements.

In the included studies, there were reports of not major adverse events associated with acupuncture, such as slight ecchymosis, nominal bleeding, swelling, and bruising at the site of acupuncture. However, it is important to note that these adverse events did not occur when using TEAS, a non-invasive technique. For patients with cancer who have platelet dysfunction, TEAS can be considered as an alternative to acupuncture for improving symptoms and pain related to CIPN. This substitution is beneficial because it helps to avoid the risk of bleeding tendencies associated with acupuncture. Although TEAS may require a longer course of intervention to effectively reduce CIPN symptoms, particularly in cases of neuropathic, intermittent, and continuous pain [67], it offers several mechanisms that contribute to its effect. TEAS may improve CIPN symptoms is by reducing excitability and enhancing inhibition of the central nervous system. CIPN symptoms are partially attributed to increased excitability and decreased inhibition, and TEAS has been shown to address these factors [11]. Furthermore, evidence suggests that TEAS activates opioid receptors, which play a role in pain inhibition [68, 69]. Electrical stimulation through TEAS also triggers the release of neuroactive substances and inhibits glial cell activation in the peripheral nervous system, contributing to its analgesic effects [61]. The analgesic effects of TEAS have been observed in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy [70]. Additionally, a systematic review confirmed that TEAS has a positive effect on motor nerve conduction velocity and improves diabetic peripheral neuropathy [71].

Acupuncture-related interventions, particularly acupuncture-M, demonstrated the potential to improve QoL in this study. Moxibustion, which involves applying a heat source to acupoints, may provide local somatothermal stimulation and affect oxidative stress in the viscera [72]. However, inconsistencies were observed between direct and indirect comparisons of the intervention effects on QoL, leading to variations in the results of this study. Although these inconsistencies did not alter the overall findings, they did lower the evidence level. The absence of direct comparisons between acupuncture-M and supplements may contribute to discrepancies arising from the transitivity of indirect comparisons [73]. Additionally, the reliance on subjective measurements through questionnaires and the small number of studies included in the loop [74], and the use of various control groups [73] may also lead to inconsistencies between direct and indirect. Measuring QoL is inherently complex and requires careful consideration. A significant challenge in network meta-analysis is managing the inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence for acupuncture-M comparisons.

Additionally, the impact of acupuncture-related interventions on CIPN symptoms and pain in this study was not influenced by the presence or absence of blinding procedures. However, in the yes-blind group, non-significant effects on CIPN QoL, which may be attributed to the small sample size. Blinding patients and researchers to interventions is challenging due to the nature of acupuncture-related interventions. A previous study indicated that there was no significant difference in intervention effects between trials with and without blinded participants, healthcare providers, or outcome assessors [75]. Conversely, another study found that intervention effects were overestimated in unblinded trials [76]. Adhering to evidence-based standards is crucial to minimizing the risk of bias and improving the quality of evidence in future RCTs.

This study has several limitations. First, blinding of participants and researchers in the included studies was either not reported or not performed, which somehow led to within-study bias. Due to the nature of acupuncture, the stimulation of acupoints with needles or electricity is always perceived by patients and known to practitioners. This study suggests employing blinding procedures whenever possible. If the outcome evaluators were blinded, measurement bias would be minimized. Similarly, if the statistical analysts were blinded, detection bias would be minimized. Second, direct and indirect comparisons of data from multiple studies may result in some inconsistencies, limiting the robustness and precision of the results. While this issue did not affect the network meta-analysis results, it did decrease the evidence level. It is also important to note the insufficient number of studies, which could impact the transitivity of indirect comparisons. Last, only published Chinese and English studies were included, which may have led to language bias.

Conclusions

In clinical practice, although interruption or reduction in the dose of chemotherapy is the recommended treatment for CIPN, such approach hampers the effect of chemotherapeutic agents on tumor growth control. However, these patients suffering from CIPN represents a significant burden on physical health and daily life. This systematic review and network meta-analysis provides clinical professionals and patients with scientific evidence and a range of options based on the hierarchical effects of acupuncture-related interventions. This study confirmed the benefits of acupuncture-related interventions, especially acupuncture-E, in improving symptoms, pain and QoL associated with CIPN for patients undergoing chemotherapy. Acupuncture-E had the most significant impact and was effective for a minimum duration of 3 weeks. Additionally, TEAS was identified as a noninvasive and feasible alternative for patients who had concerns about needles or the risk of bleeding. However, it is recommended that TEAS should be carried out for a longer period, preferably lasting 4 weeks, in order to achieve optimal outcomes. Acupuncture-M was the most effective approach in improving QoL. Few included studies reported adverse events but the relative safety of acupuncture-related interventions requires further study. Overall, acupuncture-related interventions had few complications and demonstrated high safety and accessibility, improving CIPN symptoms, pain and QoL in patients. Large-sample, randomized controlled trials are warranted to investigate CIPN caused by different chemotherapeutics, cancer types and staging to clarify the advantages of acupuncture-related interventions.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional information files.

Abbreviations

- Acupuncture-E:

-

Acupuncture plus electrical stimulation

- Acupuncture-M:

-

Acupuncture plus moxibustion

- CIPN:

-

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy

- NMA:

-

Network meta-analysis

- PICO:

-

Participants, intervention, comparison, and outcome

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- RCTs:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- TEAS:

-

Transcutaneous electrical acupoint/nerve stimulation

References

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN guidelines: colon cancer. 2021. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1428. Accessed 20 May 2021.

Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(5):363–85. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21565.

Zajaczkowska R, Kocot-Kepska M, Leppert W, Wrzosek A, Mika J, Wordliczek J. Mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(6):1451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20061451.

Wang YJ, Chan YN, Jheng YW, Wu CJ, Lin MW, Tseng LM, et al. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in newly diagnosed breast cancer survivors treated with taxane: a prospective longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(6):2959–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05796-0.

Brami C, Bao T, Deng G. Natural products and complementary therapies for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;98:325–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.11.014.

Loprinzi CL, Lacchetti C, Bleeker J, Cavaletti C, Chauhan DL, Hertz MR, et al. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: ASCO guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(28):3325–48. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.01399.

Tzatha E, DeAngelis LM. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Oncology (Williston Park). 2016;30(3):240–4.

Bonhof CS, van de Poll-Franse LV, Wasowicz DK, Beerepoot LV, Vreugdenhil G, Mols F. The course of peripheral neuropathy and its association with health-related quality of life among colorectal cancer patients. J Cancer Surviv. 2021;15(2):190–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00923-6.

Prieto-Callejero B, Rivera F, Fagundo-Rivera J, Romero A, Romero-Martín M, Gómez-Salgado J, et al. Relationship between chemotherapy-induced adverse reactions and health-related quality of life in patients with breast cancer. Medicine. 2020;99(33): e21695. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000021695.

Makker PG, Duffy SS, Lees JG, Perera CJ, Tonkin RS, Butovsky O, et al. Characterisation of immune and neuroinflammatory changes associated with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1): e0170814. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170814.

Kandula T, Farrar MA, Kiernan MC, Krishnan AV, Goldstein D, Horvath L, et al. Neurophysiological and clinical outcomes in chemotherapy-induced neuropathy in cancer. Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;128(7):1166–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2017.04.009.

Velasco R, Besora S, Argyriou AA, Santos C, Sala R, Izquierdo C, et al. Duloxetine against symptomatic chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity in cancer survivors: a real world, open-label experience. Anticancer Drugs. 2021;32(1):88–94. https://doi.org/10.1097/CAD.0000000000001005.

Alsharif F. Discovering the use of complementary and alternative medicine in oncology patients: a systematic literature review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021;2021:6619243. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6619243.

Samuels N, Ben-Arye E. Integrative approaches to chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Curr Oncol Rep. 2020;22(3):23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-020-0891-2.

Baviera AF, Olson K, Paula JM, Toneti BF, Sawada NO. Acupuncture in adults with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2019;27: e3126. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.2959.3126.

Zhu H. Acupoints initiate the healing process. Med Acupunct. 2014;26(5):264–70. https://doi.org/10.1089/acu.2014.1057.

Yeh ML, Lin KC, Chen HH, Wang YJ, Huang YC. Use of traditional medicine and complementary and alternative medicine in Taiwan: a multilevel analysis. Holist Nurs Pract. 2015;29(2):87–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/HNP.0000000000000071.

Chien TJ, Liu CY, Fang CJ, Kuo CY. The efficacy of acupuncture in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Integr Cancer Ther. 2019;18:1534735419886662. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735419886662.

Oh PJ, Kim YL. Effectiveness of non-pharmacologic interventions in chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2018;48(2):123–42. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2018.48.2.123.

Hwang MS, Lee HY, Choi TY, Lee JH, Ko YS, Jo DC, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of acupuncture and electro-acupuncture against chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Medicine. 2020;99(17): e19837. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000019837.

Kuang B, Li M, Zeng H, MO A. Meta-analysis of electroacupuncture for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Tianjin J Tradit Chin Med. 2019;(7):673–8. https://doi.org/10.11656/j.issn.1672-1519.2019.07.13.

Hao J, Zhu X, Bensoussan A. Effects of nonpharmacological interventions in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Integr Cancer Ther. 2020;19:1534735420945027. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735420945027.

Jin Y, Wang Y, Zhang J, Xiao X, Zhang Q. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture against chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020;2020:8875433. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8875433.

Yeh ML, Hsu CC, Chen CH. Traditional Chinese medicine in nursing care. 3rd ed. Taiwan: Wunan; 2020.

Higgins JPT, Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Hróbjartsson A, Boutron I, et al. A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10(Supp 1):29–31.

Salanti G, Ades AE, Ioannidis JP. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(2):163–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.016.

Bao T, Patil S, Chen C, Zhi IW, Li QS, Piulson L, et al. Effect of acupuncture vs sham procedure on chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3): e200681. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0681.

Bao T, Baser R, Chen C, Weitzman M, Zhang YL, Seluzicki C, et al. Health-related quality of life in cancer survivors with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a randomized clinical trial. Oncologist. 2021;26(11):e2070–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/onco.13933.

Cao SC, Zhong Y, Zhang HS, Zhang SQ, Zhuang HW, Wang ZM, et al. Electroacupuncture reduces peripheral neurotoxicity and improves quality of life in cancer patients with Vinca alkaloids chemotherapy. J Pract Oncol. 2015;30(4):374–7. https://doi.org/10.13267/j.cnki.syzlzz.2015.04.046.

Chang WW. Clinical trial of electroacupuncture stimulation on prevention and treatment of oxaliplatin neurotoxicity (Master Dissertation). China’s mainland: Dalian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine; 2018.

Cui DL, Wang LX, Fu CJ. Clinical observation of moxibustion-acupuncture and in the treatment of oxaliplatin neurotoxicity. Gansu J Tradit Chin Med. 2011;24(2):45–6.

Dai LJ, Xu BG, Wang J. Effect of needle warming moxibustion on cancer chemotherapy-induced toxicity and side effect. Hebei J Tradit Chin Med. 2011;33(8):1191–2, 1195.

Han X, Wang L, Shi H, Zheng G, He J, Wu W, et al. Acupuncture combined with methylcobalamin for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in patients with multiple myeloma. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-3037-z.

Hou HK, Cheng HY. Effect of acupuncture on chemotherapy-related peripheral neurotoxicity and digestive tract adverse effects of malignant tumor patients: a clinical study on 20 cases. J Tradit Chin Med. 2011;52(23):2031–3. https://doi.org/10.13288/j.11-2166/r.2011.23.015.

Iravani S, Kazmi Motlagh AH, Emami Razavi SZ, Shahi F, Wang J, Hou L, et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture treatment on chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a pilot, randomized, assessor-blinded, controlled trial. Pain Res Manag. 2020;2020:2504674. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/2504674.

Kong FH. Clinical observation of electro-acupuncture combined with chemotherapy for the prevention and treatment of peripheral neurotoxicity caused by docetaxel [Conference presentation]. 2nd annual conference of acupuncture and rehabilitation branch of the Chinese association for the promotion of traditional Chinese medicine and the 9th annual meeting of the Shandong Acupuncture and Moxibustion Society, 3. 2017.

Li DQ, Luo JQ, Zhang H. Effect on the prevention and treatment of neurotoxicity of malignant tumor by electroacupuncture after chemotherapy. China J Chin Med. 2012;27(8):928–30. https://doi.org/10.16368/j.issn.1674-8999.2012.08.006.

Lin JY. Clinical observation on the effect of improved treatment of acupuncture on treating CIPN with Qi deficiency and blood stasis (Master Dissertation). China’s mainland: Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine; 2019.

Lou B, Zhang LW, Xu K, Luo HY, Li Y. Clinical observation on acupuncture treatment of peripheral nervous system toxicity induced by chemotherapy drugs. Hebei J Tradit Chin Med. 2009;31(7):1040–1.

Lu W, Giobbie-Hurder A, Freedman RA, Shin IH, Lin NU, Partridge AH, et al. Acupuncture for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Oncologist. 2020;25(4):310–8. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0489.

Molassiotis A, Suen LKP, Cheng HL, Mok TSK, Lee SCY, Wang CH, et al. A randomized assessor-blinded wait-list-controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of acupuncture in the management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Integr Cancer Ther. 2019;18:1534735419836501. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735419836501.

Pan XJ, Gu F, Huang LH, Li YM. Clinical study on transcutaneous electrical acupuncture for prevention of peripheral neuritis in patients with lung cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Chin Nurs Res. 2018;32(20):3274–7. https://doi.org/10.12102/j.issn.1009-6493.2018.20.029.

Rostock M, Jaroslawski K, Guethlin C, Ludtke R, Schröder S, Bartsch HH, et al. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in cancer patients: a four-arm randomized trial on the effectiveness of electroacupuncture. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013: 349653. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/349653.

Stringer J, Ryder WD, Mackereth PA, Misra V, Wardley AM. A randomised, pragmatic clinical trial of ACUpuncture plus standard care versus standard care alone FOr Chemotherapy Induced peripheral Neuropathy (ACUFOCIN). Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2022;60: 102171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2022.102171.

Su ZJ. Clinical research of intradermal acupuncture for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in patients with gastric cancer or colorectal cancer (Master Dissertation). China’s mainland: Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine; 2019.

Sui MH, Xu N, Xiang Y, Shu GJ, Jin DM, Yan TB. The influence of electrical acupuncture on the chemotherapy induced neuropathic pain and quality of life. Chin J Integr Med Cardio-/Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;16(10):1331–3. https://doi.org/10.12102/j.issn.1672-1349.2018.10.06.

Sun XJ, He SL, Chen H, Shen J, Wu WB, Liu LM, et al. Clinical study of electroacupuncture treatment for oxaliplatin neurotoxicity. Shanghai J Acupunct Moxibustion. 2012;31(10):727–9. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1005-0957.2012.10.727.

Tian YP, Zhang Y, Jia YJ. The curative effect of warm acupuncture and moxibustion on peripheral neurotoxicity caused by oxaliplatin. Tianjin J Tradit Chin Med. 2011;28(6):212–3.

Tian HZ. The clinical observation of curative effect acupuncture on chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy caused by FOL-FOX4 regimen (Master Dissertation). China’s mainland: Heilongjiang University of Traditional Chinese Medicine; 2016.

Wang B. Clinical study of peripheral neuropathy caused by acupuncture in patients with colorectal cancer oxaliplatin chemotherapy (Master Dissertation). China’s mainland: Beijing University of Chinese Medicine; 2011.

Wang YH. Influence on the toxicity and side effects of malignant tumor chemotherapy with fire needle on sihua points (Master Dissertation). China’s mainland: Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine; 2014.

Wang B. Clinical study on electroacupuncture combined with mecobalamin in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in multiple myeloma (Master Dissertation). China’s mainland: Gansu University of Chinese Medicine; 2018.

Wang L, Xu X, Yao L, Huang Y, Zou Q, Wu B, et al. Intervention effect of acupuncture and moxibustion in treatment of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in patients with multiple myeloma. J Clin Med Pract. 2022;26(2):28–30. https://doi.org/10.7619/jcmp.20212712.

Wong R, Major P, Sagar S. Phase 2 study of acupuncture-like transcutaneous nerve stimulation for chemotherapy-Induced peripheral neuropathy. Integr Cancer Thera. 2016;15(2):153–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735415627926.

Wu Y, Zeng Y, Leng Y. Clinical observation of acupuncture prevention and cure effect on the nitrobenzene induced neurotoxicity in the circuit of chemotherapy period. Clin J Tradit Chin Med. 2018;30(4):725–8. https://doi.org/10.16448/j.cjtcm.2018.0219.

Xiang Y, Xu N, Sui MH. Clinical observation on electroacupuncture in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced pathologic neuropathyic pain. Chin J Integr Med Cardio-/Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;16(9):1168–71.

Xu WR, Hua BJ, Hou W, Bao YJ. Clinical randomized controlled study on acupuncture for treatment of peripheral neuropathy induced by chemotherapeutic drugs. Chin Acupunct Moxibustion. 2010;30(6):457–60. https://doi.org/10.13703/j.0255-2930.2010.06.011.

Yan YJ, He CL, Dong CH. Clinical study on acupuncture for treatment of peripheral neuropathy induced by chemotherapeutic drugs. J Liaoning Univ Tradit Chin Med. 2012;14(8):232–3. https://doi.org/10.13194/j.jlunivtcm.2012.08.232.yanyj.075.

Zhang S, Wu T, Zhang H, Yang Y, Jiang H, Cao S, et al. Effect of electroacupuncture on chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in patients with malignant tumor: a single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. J Tradit Chin Med. 2017;37(2):179–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0254-6272(17)30042-0.

Dou B, Li Y, Ma J, Xu Z, Fan W, Tian L, et al. Role of neuroimmune crosstalk in mediating the anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects of acupuncture on inflammatory pain. Front Neurosci. 2021;15: 695670. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.695670.

Li N, Guo Y, Gong Y, Zhang Y, Fan W, Yao K, et al. The anti-inflammatory actions and mechanisms of acupuncture from acupoint to target organs via neuro-immune regulation. J Inflamm Res. 2021;14:7191–224. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S341581.

Jiang K, Sun Y, Chen X. Mechanism underlying acupuncture therapy in spinal cord injury: a narrative overview of preclinical studies. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13: 875103. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.875103.

Liddle CE, Harris RE. Cellular reorganization plays a vital role in acupuncture an algesia. Med Acupunct. 2018;30(1):15–20. https://doi.org/10.1089/acu.2017.1258.

Lv Q, Wu F, Gan X, Yang X, Zhou L, Chen J, et al. The involvement of descending pain inhibitory system in electroacupuncture-induced analgesia. Front Integr Neurosci. 2019;13:38. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2019.00038.

Lai HC, Lin YW, Hsieh CL. Acupuncture-analgesia-mediated alleviation of central sensitization. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019;2019:6173412. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6173412.

Han QQ, Fu Y, Le JM, Ma YJ, Wei XD, Ji HL, et al. The therapeutic effects of acupuncture and electroacupuncture on cancer-related symptoms and side-effects. J Cancer. 2021;12(23):7003–9. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.55803.

Gewandter JS, Chaudari J, Ibegbu C, Kitt R, Serventi J, Burke J, et al. Wireless transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation device for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: an open-label feasibility study. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(5):1765–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4424-6.

Bi Y, Wei Z, Kong Y, Hu L. Supraspinal neural mechanisms of the analgesic effect produced by transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. Brain Struct Funct. 2021;226(1):151–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-020-02173-9.

Gozani SN. Remote analgesic effects of conventional transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation: a scientific and clinical review with a focus on chronic pain. J Pain Res. 2019;12:3185–201. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S226600.

Serry ZMH, Mossa G, Elhabashy H, Elsayed S, Elhadidy R, Azmy RM, et al. Transcutaneous nerve stimulation versus aerobic exercise in diabetic neuropathy. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatr Neurosurg. 2016;53(2):124–9. https://doi.org/10.4103/1110-1083.183449.

Zeng H, Pacheco-Barrios K, Cao Y, Li Y, Zhang J, Yang C, et al. Non-invasive neuromodulation effects on painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):9184. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75922-9.

Chiu JH. How does moxibustion possibly work? Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:198584. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/198584.

Veroniki AA, Vasiliadis HS, Higgins JP, Salanti G. Evaluation of inconsistency in networks of interventions. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(1):332-45. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys222.

Song F, Xiong T, Parekh-Bhurke S, Loke YK, Sutton AJ, Eastwood AJ, et al. Inconsistency between direct and indirect comparisons of competing interventions: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ. 2011;343:d4909. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4909.

Moustgaard H, Clayton GL, Jones HE, Boutron I, Jørgensen L, Laursen DRT, et al. Impact of blinding on estimated treatment effects in randomised clinical trials: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ. 2020;368:l6802. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6802.

Martin GL, Trioux T, Gaudry S, Tubach F, Hajage D, Dechartres A. Association between lack of blinding and mortality results in critical care randomized controlled trials: a meta-epidemiological study. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(10):1800-11. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000005065.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ML Yeh: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. RW Liao: Conceptualization, Investigation. PH Yeh: Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Writing-original draft. CJ Lin: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing, Visualization. YJ Wang: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Writing-review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yeh, ML., Liao, RW., Yeh, PH. et al. Acupuncture-related interventions improve chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Complement Med Ther 24, 310 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-024-04603-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-024-04603-1