Abstract

Background

The often poor prognosis associated with cancer necessitates empowering patients to express their care preferences. Yet, the prevalence of Advance Directives (AD) among oncology patients remains low. This study investigated oncologists' perspectives on the interests and challenges associated with implementing AD.

Methods

A French national online survey targeting hospital-based oncologists explored five areas: AD information, writing support, AD usage, personal perceptions of AD's importance, and respondent's profile. The primary outcome was to assess how frequently oncologists provide patients with information about AD in daily clinical practice. Additionally, we examined factors related to delivering information on AD.

Results

Of the 410 oncologists (50%) who responded to the survey, 75% (n = 308) deemed AD relevant. While 36% (n = 149) regularly inform patients about AD, 25% (n = 102) remain skeptical about AD. Among the respondents who do not consistently discuss AD, the most common reason given is the belief that AD may induce anxiety (n = 211/353; 60%). Of all respondents, 90% (n = 367) believe patients require specific information to draft relevant AD. Physicians with experience in palliative care were more likely to discuss AD (43% vs 32.3%, p = 0.027). Previous experience in critical care was associated with higher levels of distrust towards AD (31.5% vs 18.8%, p = 0.003), and 68.5% (n = 281) of the respondents expressed that designating a “person of trust” would be more appropriate than utilizing AD.

Conclusion

Despite the perceived relevance of AD, only a third of oncologists regularly apprise their patients about them. Significant uncertainty persists about the safety and relevance of AD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Despite the recent tremendous progress in cancer care, cancerous diseases are still associated with a poor prognosis, with only 25% five-year survival after diagnosis [1]. Due to the immunologic dysfunction and frailty associated with cancer as well as treatment side effects [2], 15% of patients living with cancer will require admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) during their lives [3]. However, critical care, with a mortality rate up to 58%, poses a significant burden on patients. Not only is ICU care associated with notable patient discomfort [4], but survivors also encounter multiple challenges. These include increased mortality rate, diminished quality of life (with up to 50% of patients experiencing depression after critical care hospitalization [5] and 20% suffering from post-traumatic stress syndrome [6]), and altered autonomy (with only 50% of patients able to resume their previous activities five years after receiving critical care) [7]. It may also create unrealistic expectations among their relatives [4]. This significant impact on patients’ recovery, quality of life, and potential sequelae after critical care underscores the importance of understanding what is or is not acceptable for each individual patient. This understanding enables the delivery of the most appropriate and tailored care possible.

While a patient's prognosis and physiological reserve are often known and taken into account when determining ICU admission, it is common for patients in need of critical care to be unable to express their care preferences. To address this problem, Advance Directives (AD) were created, allowing patients to have a voice in their treatment decisions under all circumstances. The concept of AD was originally proposed and publicly introduced by Louis Kutner in the Indiana Law Journal in 1969 [8]. It was later legally implemented in the United States with the Patient Self-Determination Act in 1990. In Europe, this concept was adopted into the legal framework during the Oviedo Convention in 1997 and was subsequently recognized in France through the Loi Leonetti [9]. Current French law defines AD as a means for patients to express their wishes regarding the intensity of care, potential refusal of medical or surgical interventions, and their end-of-life care preferences [10]. By facilitating written, anticipatory expression of living wills by patients, AD serve as a crucial document in critical and life-threatening situations that necessitate swift, ethical decision-making. While AD have been part of the legal framework of patient care since 2005, have been medically binding since 2016, and have been promoted nationally by a specialized agency for end-of-life care (Centre National de la Fin de Vie et des Soins Palliatifs), fewer than 5% of French patients living with cancer have drafted their AD [11, 12]. Although factors such as a lack of information and the difficulties patients encounter in envisioning future circumstances [13] may contribute to the sparse use of AD, we investigated the possibility that medical hesitancy in applying these provisions may be another factor in the underutilization of AD. The main objective of this study was to assess how frequently information about AD is provided to patients in the daily clinical practice of oncologists. The secondary objectives focused on understanding the barriers to implementing AD within this context.

Methods

Study design

This study is a prospective, observational, cross-sectional study. It is based on volunteer participation and adheres to the applicable CROSS guidelines [14].

Study population

All oncologists who were working full-time or part-time in a hospital setting at the initiation of the study were contacted to participate, including those at teaching hospitals, tertiary care hospitals, and cancer centers (the full list can be found in the Supplementary materials). Oncologists who worked exclusively in a private practice setting, physicians from non-oncological specialties, and resident physicians were excluded from the study.

Precautions

No judgment was made regarding the use, compliance, or, conversely, the lack of application of AD — including AD information dissemination, documentation, and implementation. Details of the precautions taken during the study are described in the Supplementary materials.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was built according to the redaction guidelines for this type of instrument [15,16,17,18]. The various themes included in the questionnaire were selected using a Delphi procedure. The experts of the REQUIEM group determined which themes to include and proposed an initial draft of the questionnaire based on literature and critical elements identified in previous work [19,20,21,22,23,24]. This draft was then reviewed by experts from the French Society of Cancerology (SFC: Société Française de Cancérologie) and the French Society of bone marrow transplant and cellular therapy (SFGM-TC: Société Francophone de Greffe de moelle et de Thérapie cellulaire).

Five domains were chosen to structure a 19-item questionnaire: clinicians’ engagement in providing information about the existence of AD, clinicians’ involvement in writing AD, utilization of existing AD in case of an acute situation, information about the respondent’s department, and personal data regarding the respondent. The questionnaire was then pretested by various members of the REQUIEM group, consisting of intensivists, palliative care physicians, general practitioners, and pharmacists. However, we did not conduct a pilot study to avoid potential loss of respondents. The complete questionnaire is available in Appendix 1.

Questionnaire administration

In June 2020 a center-specific link was generated and disseminated to respondents via email to access the electronic survey, which was stored and administered using Googleform®. We sent several reminders via telephone or email to the attending physicians across all the centers from mid 2020 to mid 2021. Centers were also notified of their response rate in comparison to other centers. The questionnaire was closed in June 2021.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was to assess the frequency at which information about AD is provided to patients in the daily clinical practice of oncologists. Secondary outcomes were factors influencing the provision of information about AD, assistance with AD drafting, physicians’ actual use of AD, possible means of improving the usage of AD, including the information needed to draft them according to the clinician’s experience, and the potential role of the “person of trust” (see definition in Supplementary materials).

Statistical analysis

Data synthesis is presented as mean values and standard deviations (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). The relationship between two qualitative parameters was evaluated using the Chi-square test. Differences were deemed significant if the alpha risk of identifying a non-existent difference was less than 5% (p ≤ 0.05).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki. This research falls under the French reference methodology MR003, and ethical approval was obtained from an ethics committee (Groupe Ethique & Rercherche Médicale—GERM. IRB 00012157). According to MR003 this type of research does not require specific consent (“Recherches dans le domaine de la santé sans recueil du consentement” Official text. Delibération n° 2018–154 of May 3, 2018; text n°109 of the Journal officiel de la République française). In this scenario, the ethics committee did not require a formal consent from participants. The respondents were informed about the study in writing, via an introductory paragraph at the beginning of the questionnaire. If a respondent did not reply to the questionnaire, it was considered as a refusal to participate in the study. On the other hand, completion of the questionnaire constituted de facto agreement to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Results

Population

Between June 2020 and June 2021, 410 out of 818 oncologists who met the study criteria responded to the questionnaire. This represents a 50% response rate from oncologists working in 60 hospitals across France (Fig. 1). The respondents consisted of fellows (n = 101, 24.6%), attending physicians (n = 270, 65.9%) and professors (n = 39, 9.5%). This distribution accurately reflects the medical demographics in France. Of the respondents, 234 physicians (57.1%) work in cancer centers and 152 (37.1%) work in teaching hospitals (details in Table 1).

Reported frequency of information provided to patients on Advance Directives (AD)

Based on the responses, 36.3% (n = 149) of oncologists “often” or “systematically” discuss AD with their patients, while 59% (n = 241) do so “sometimes”. Of the respondents, 5% (n = 20) reported never discussing AD with their patients. These results are in Fig. 2.

Factors Influencing the Provision of Information on AD

Demographic factors associated with more frequent discussions on AD include experience in palliative care (p = 0.027), working at a cancer center (p = 0.022), and increased professional experience (e.g., attending physicians are significantly more likely to discuss AD than fellows, p = 0.021) (see Appendix 3).

Among the respondents who discuss AD with their patients, the main triggers driving these discussions include a patient’s questions about prognosis or vital risk, seen as a favorable context for 68.2% (n = 266) of the respondents. Other triggers include disease progression despite active treatment (n = 256; 65.6%), the occurrence of a complication requiring hospitalization (n = 209; 53%) and the presence of metastatic disease (n = 69; 17.7%) (Fig. 3).

Oncologists who do not routinely discuss AD often cite their concern about causing anxiety for the patient (n = 211; 59.8%) or their relatives (n = 95; 26.9%) as a primary reason. Other significant reasons include the perception that AD are not suitable for a chronic medical situation (n = 135; 38.2%), for end-of-life care (n = 86; 24.4%), or for meeting the overall needs of patients (n = 70; 19.8%), and 69 respondents (19.5%) voiced concern that patients may not know how to utilize AD (details in Fig. 4).

There may also be a reluctance to use AD due to their perceived potential harmful implications. Indeed, 25% (n = 102) of the respondents express significant concerns regarding AD. Only 31 respondents (7.6%) believe that AD are perfectly suited to cover patients’ needs (Fig. 5). Furthermore, 56.8% (n = 233) of respondents feel that the responsibility to provide information on AD should lie with someone else, such as the primary care physician, state agency, or another entity (Appendix 2).

Use of AD in clinical practice

Of the respondents, 32% (n = 130) have assisted their patients in drafting their AD. Physicians who often discuss AD were more likely to have aided their patients in this process (p = 0.0005) (Appendix 4). Additionally, 50.9% (n = 209) of respondents stated that they collect AD and 46.8% (n = 192) said that they formally collect decisions regarding treatment limitations. When respondents had access to AD, 90.2% (n = 370) reported adhering to them. 9.8% (n = 40) clinicians said they sometimes disregarded AD. Within this subgroup, the reasons cited for not respecting the AD were urgent situations that fell outside the scope of patients’ end-of-life care (87%, n = 35) or concern that the patient may have changed their mind (35.0%, n = 14).

Potential improvement of AD usage

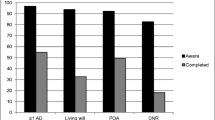

Although currently underutilized, 75.1% (n = 308) of respondents perceive AD as a valuable tool. In fact, 89.5% (n = 367) of the responding oncologist believe that patients require additional information to effectively write their AD. Additional information they highlighted include information on their general care (n = 275; 74.5%), their prognosis (n = 248, 67.6%), available treatments (n = 135, 36.8%), how to use AD (n = 261; 71.1%), and specific medical terminology (n = 229; 62.4%) (Fig. 6).

Person of trust

Systematic recording and tracking of information about the person of trust designated by the patient was reported by 86.1% (n = 350) of respondents, and 73.6% (n = 302) acknowledged having a specific section in their medical records dedicated for documenting this information.

Of respondents, 52.4% (n = 215) “systematically” discuss the concept of the person of trust with their patients, while only 19% (n = 80) “rarely” or “never” broach the topic. Furthermore, 68.5% (n = 281) of the respondents believe that designating a trust person would be a more effective tool than AD for managing patients’ care. This sentiment was notably more prevalent among younger physicians (Appendix 5).

Discussion

In our national survey, we found that 36% of respondents regularly, if not systematically, discuss AD with their patients. The topic of AD is more likely to be addressed when patients express a desire for information about prognosis or vital risk or when their condition deteriorates. On the other hand, the trepidation of creating anxiety for the patient or their relatives, especially in the case of a stable and chronic disease, is a significant factor deterring the mention of AD. Ultimately, oncologists regard the designation of a person of trust as an important means for conveying patients’ wishes.

This study highlights a significant challenge in the use of AD: the ambivalence felt by clinicians. While 47% of respondents see AD as a means to reassure their patients, the predominant reason cited for not discussing AD is the fear of causing distress. This fear, [25] as well as the concern about impacting the therapeutic relationship [26] are often noted in the literature. However, a large multicenter study found discussing prognosis, including the progression of tumor diseases and end-of-life scenarios did not cause harmful effects [27]. In fact, early discussion of advance care plans may even provide psychological benefits and lessen the risk of unwanted aggressive care [27,28,29], which has been shown to negatively impact patients’ quality of life [27, 28, 30, 31].

The timing of discussing AD represents a significant challenge for physicians. Our study revealed the majority of oncologists consider it preferable to wait for a favorable context, typically marked by patient’s inquiries about their disease prognosis or the vital risk associated with the tumor. However, the vast majority of patients seem to prefer that their physicians initiate such discussions rather than the patients themselves [26, 32,33,34]. While the most appropriate timeframe for these discussion is still uncertain, recent studies have confirmed the feasibility of systematically informing patients with severe tumor diseases about AD at an early stage [35, 36].

While the legislative framework [37, 38] and educational training [39] of medical students have evolved over recent decades to prioritize patient autonomy in care processes, young clinicians often remain hesitant to discuss AD with their patients. This trend is evidenced by a study involving young general practitioners; despite broadly supporting the implementation of the provision, they only considered malignant disease diagnosis as an opportunity to inform their patients in 60% of cases [23]. These findings underscore the importance of developing training programs that include comprehensive information on the safety and benefits of initiating discussions about AD [32, 40]. Simulation-based communication-training programs may prove effective for this purpose [41, 42]. Additionally, a potential strategy for enhancing the implementation of AD could involve systematically providing information on AD existence and collection during the initial management of patients, regardless of disease severity [43].

To overcome the challenges associated with AD, 68.5% of the respondents believe that designating a person of trust would be more applicable for patient care due to its dynamic nature. The role of a person of trust appears to be favored by patients as well. In two independent studies (HELP [44] and SUPPORT [45]) conducted among elderly and cancer patients, 70% and 78% of respondents respectively were comfortable with their loved ones making medical decisions on their behalf if they were to become incapacitated [46]. However, patients seldom discuss their preferences for medical care, particularly in hypothetical critical and severe scenarios, with their relatives or persons of trust. The agreement between a patient's decisions and those of their person of trust can be as low as 30% [44, 47, 48]. Similarly, both physicians and persons of trust seem incapable of accurately gauging what their patient or relative would consider as an acceptable quality of life [49]. The role of a person of trust is not without responsibilities. Involvement in the decision to escalate therapy can be a source of psychological distress for the patient's relatives, especially for the person of trust [50]. Furthermore, the person of trust may be more inclined to prioritize keeping their loved one alive, possibly at the expense of the patient’s comfort [51]. Therefore, if the person of trust is to become a primary participant in the care of an incapacitated patient, they should not replace AD, but rather function in conjunction with these directives.

Beyond the communication challenges related to AD, disease prognosis, or end-of-life discussions; our findings highlight a significant issue; clinicians often believe they can determine when a patient should record their own preferences regarding care intensity. This restriction of patient’s choice, illustrated by the absence of information about AD when the situation is medically deemed inappropriate or the presumed inadequacy of AD to meet patient needs, along with persistent failure to comply with existing AD, tend to suggest persistent medical paternalism. While patient autonomy is universally acknowledged as a central element of patient care, it is evident that numerous scenarios are still deemed as exceptions [52]. The capacity of patients to anticipate their wishes in the case of cognitive decline is a central point in this debate [53, 54], and similar issues come to the forefront during the management of cancer [33]. Additionally, a study involving over 4000 oncologists in the United-States revealed heightened hesitation to discuss care intensity or end-of-life preference, compared to non-oncologist physicians [33]. However, the lack of discussion regarding AD does not necessarily equate to an absence of dialogue about disease prognosis or patients' care preferences [33]. While our study is not equipped to address this particular query, the overall commitment demonstrated by the respondents could be interpreted as a desire to offer the best possible care to patients, regardless of the presence of AD. Similarly, the lack of introduction of AD and pre-planning of care may reflect i) the physician's uncertainty regarding the predictability of the disease's progression [54, 55], and ii) the perception that patients require more comprehensive information to make accurate decisions [53, 55], as illustrated in the potential improvement section of our work. Unfortunately, the demand for more comprehensive data regarding the disease's status may obscure the perceived inability of patients to determine their "best interest" [53, 56, 57], which is another manifestation of medical paternalism. These observations underscore the importance of clarifying the distinction between “medical expertise (which refers to specialized knowledge in a certain area) and “medical authority” (the assumed prerogative to make decisions based on that knowledge) [58].

This study does have limitations. For instance, the response rate is not entirely satisfactory. However, to our knowledge, this is the first and largest study of its kind conducted among French hospital oncologists. Furthermore, the representativeness of the study appears to be preserved given that responses are widely distributed across the country, and the distribution among fellows, attendings, and professors mirrors the real-life demographic spread.

Our survey was accessible at each center for a year. The unique link was closed as soon as all potential respondents completed the survey. This extended period may impact the results in different ways. First, the study may have stimulated discussions about AD among colleagues potentially leading to modifications in local practices related to this subject. Second, practices may have evolved over the course of a year in France owing to continuous improvements in clinical practice and a growing awareness of the challenges associated with end-of-life care, particularly in the context of the ongoing public debate about end-of-life decisions and euthanasia in the country. However, these factors could result in a potential over-reporting of AD use. Despite this, our current results still underscore potential strategies for enhancing the broader usage of AD.

Another limitation of the study is the recruitment bias. The oncologists who chose to respond to the questionnaire are likely those most invested in the concept of AD. Moreover, the proportion of responding practitioners with palliative care experience (37%) is greater than in the general population of French oncologists. Accordingly, these responses may skew toward being more supportive of AD compared to the general sentiment held by oncologists.

Lastly, as the responses are self-reported, there is not an absolute guarantee of their validity in day-to-day practice. Nevertheless, given the survey was anonymous and factual, without implying a need for practice change, there seem to be no distinct motives for respondents to misrepresent their views while completing the questionnaire.

Conclusion

Three-quarters of oncologists believe that AD can be useful. However, only one-third of the oncologists regularly discuss them. The primary reasons for such hesitation encompass concerns about potentially generating or amplifying patient anxiety, as well as the perception that AD may not be suitable for the patient's specific medical circumstances.

Availability of data and materials

Datasets used/analyzed in this study are accessible from the REQUIEM study group upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Advance Directives

- ICU:

-

Intensive Care Unit

- IQR:

-

Interquartile Range

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Kramer JL, Rowland JH, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:271–89.

Schellongowski P, Kiehl M, Kochanek M, Staudinger T, Beutel G. Intensive Care in Hematologic-Oncologic Patients (iCHOP). Intensive care for cancer patients: An interdisciplinary challenge for cancer specialists and intensive care physicians. Memo. 2016;9:39–44.

Puxty K, McLoone P, Quasim T, Sloan B, Kinsella J, Morrison DS. Risk of Critical Illness Among Patients With Solid Cancers: A Population-Based Observational Study. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:1078–85.

Huaringa AJ, Francis WH. Outcome of invasive mechanical ventilation in cancer patients: Intubate or not to intubate a patient with cancer. J Crit Care. 2019;50:87–91.

Hatch R, Young D, Barber V, Griffiths J, Harrison DA, Watkinson P. Anxiety, Depression and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder after critical illness: a UK-wide prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2018;22:310.

Wade D, Hardy R, Howell D, Mythen M. Identifying clinical and acute psychological risk factors for PTSD after critical care: a systematic review. Minerva Anestesiol. 2013;79:944–63.

Pfoh ER, Wozniak AW, Colantuoni E, Dinglas VD, Mendez-Tellez PA, Shanholtz C, et al. Physical declines occurring after hospital discharge in ARDS survivors: a 5-year longitudinal study. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1557–66.

Kutner L. The living will: coping with the historical event of death. Bayl Law Rev. 1975;27:39–53.

Andorno R, Biller-Andorno N, Brauer S. Advance health care directives: towards a coordinated European policy? Eur J Health Law. 2009;16:207–27.

Loi n° 2005-370 du 22 avril 2005 relative aux droits des malades et à la fin de vie. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000000446240/.

Sicard D. Penser solidairement la fin de vie. Commission de réflexion sur la fin de vie en France: Rapport à François Hollande président de la république française; 2012.

Pennec S, Monnier A, Pontone S, Aubry R. End-of-life medical decisions in France: a death certificate follow-up survey 5 years after the 2005 act of parliament on patients’ rights and end of life. BMC Palliat Care. 2012;11:25.

Serey K, Cambriel A, Pollina-Bachellerie A, Lotz J-P, Philippart F. Advance Directives in Oncology and Haematology: A Long Way to Go-A Narrative Review. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1195.

Sharma A, Minh Duc NT, Luu Lam Thang T, Nam NH, Ng SJ, Abbas KS, et al. A Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS). J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:3179–87.

Singly F de. Le questionnaire - 4e éd. 4e édition. Paris: Armand Colin; 2016. ISBN 13 : 9782200613211

Gerard MFJ. Conduite d’enquête par questionnaire. 1st edition. Editions du robot furieux - Frederic Gerard; 2015. ISBN-13 : 9782955370216

Fenneteau H. Enquête : entretien et questionnaire - 3e édition. 3e édition. Paris: Dunod; 2015. ISBN 978-2-10-072234-1

Burns KEA, Kho ME. How to assess a survey report: a guide for readers and peer reviewers. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J. 2015;187:E198–205.

Garrouste-Orgeas M, Tabah A, Vesin A, Philippart F, Kpodji A, Bruel C, et al. The ETHICA study (part II): simulation study of determinants and variability of ICU physician decisions in patients aged 80 or over. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1574–83.

Verrière C. Quelle est la place du médecin généraliste dans les décisions de limitation ou d’arrêt des thérapeutiques chez leurs patients de plus de 75 ans hospitalisés ? Thèse de doctorat. Paris V. René Descartes; 2014.

Albane Hugues. Evaluation de la connaissance et de l’usage des directives anticipées chez les internes de médecine générale. [Thèse de doctorat]. Paris VII. Denis Diderot; 2016. http://www.bichatlarib.com/publications/publications.dmg.php?phase=affichage_documents&numero_publication=1573.

Wainschtein S. Perception par les internes de médecine générale de la connaissance et de l’application des directives anticipées. Thèse de doctorat. Paris VI. Pierre et Marie Curie; 2016.

Hubert S, Wainstein S, Hugues A, Haardt V, Philippart F. Directives Anticipées & Medecine Générale : application, limites et perspectives. Données personnelles préliminaires. 2018.

Philippart F, Vesin A, Bruel C, Kpodji A, Durand-Gasselin B, Garçon P, et al. The ETHICA study (part I): elderly’s thoughts about intensive care unit admission for life-sustaining treatments. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1565–73.

Robinson CA, Fyles G, McKenzie M. Oncologist Experience Implementing Goals of Care Discussions in Everyday Ambulatory Oncology Practice: Implications for Education. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2017;32:301–7.

Boyd K, Mason B, Kendall M, Barclay S, Chinn D, Thomas K, et al. Advance care planning for cancer patients in primary care: a feasibility study. Br J Gen Pract J R Coll Gen Pract. 2010;60:e449–458.

Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, Mack JW, Trice E, Balboni T, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–73.

Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, Gallagher ER, Jackson VA, Lynch TJ, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2319–26.

Bestvina CM, Polite BN. Implementation of Advance Care Planning in Oncology: A Review of the Literature. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:657–62.

Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, Nilsson ME, Maciejewski ML, Earle CC, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:480–8.

Clayton JM, Butow PN, Tattersall MHN, Devine RJ, Simpson JM, Aggarwal G, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a prompt list to help advanced cancer patients and their caregivers to ask questions about prognosis and end-of-life care. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2007;25:715–23.

Johnson S, Butow P, Kerridge I, Tattersall M. Advance care planning for cancer patients: a systematic review of perceptions and experiences of patients, families, and healthcare providers. Psychooncology. 2016;25:362–86.

Keating NL, Landrum MB, Rogers SO, Baum SK, Virnig BA, Huskamp HA, et al. Physician factors associated with discussions about end-of-life care. Cancer. 2010;116:998–1006.

Sahm S, Will R, Hommel G. What are cancer patients’ preferences about treatment at the end of life, and who should start talking about it? A comparison with healthy people and medical staff. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:206–14.

Michael N, O’Callaghan C, Baird A, Gough K, Krishnasamy M, Hiscock N, et al. A mixed method feasibility study of a patient- and family-centred advance care planning intervention for cancer patients. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14:27.

Obel J, Brockstein B, Marschke M, Robicsek A, Konchak C, Sefa M, et al. Outpatient advance care planning for patients with metastatic cancer: a pilot quality improvement initiative. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:1231–7.

Leonetti J. Rapport de M. Jean Leonetti au nom de la mission d’information sur l’accompagnement de la fin de vie. 2004. https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/12/rap-info/i1708-t1.asp.

Alain Claeys, Léonetti J. Rapport de présentation et texte de la proposition de loi de MM. Alain Claeys et Jean Leonetti créant de nouveaux droits en faaveur des malades et des personnes en fin de vie. https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/14/rapports/r2585.asp.

Santé M des S et de la, Santé M des S et de la. Le plan national “Soins Palliatifs 2015–2018.” Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. 2021. https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/soins-et-maladies/prises-en-charge-specialisees/findevie/ameliorer-la-fin-de-vie-en-france/article/le-plan-national-soins-palliatifs-2015-2018. Accessed 7 Sep 2021.

Enzinger AC, Zhang B, Schrag D, Prigerson HG. Outcomes of Prognostic Disclosure: Associations With Prognostic Understanding, Distress, and Relationship With Physician Among Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3809–16.

Millstein LS, Rosenblatt P, Bellin MH, Whitney L, Eveland SR, Lee MC, et al. Advance Care Planning and Communication Skills Improve after an Interprofessional Team Simulation with Standardized Patients. Palliat Med Rep. 2022;3:123–31.

Chen J-O, Chang S-C, Lin C-C. The development and pilot testing of an ACP simulation-based communication-training program: Feasibility and acceptability. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0254982.

Kubi B, Istl AC, Lee KT, Conca-Cheng A, Johnston FM. Advance Care Planning in Cancer: Patient Preferences for Personnel and Timing. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16:e875–83.

Tsevat J, Dawson NV, Wu AW, Lynn J, Soukup JR, Cook EF, et al. Health values of hospitalized patients 80 years or older. HELP Investigators. Hospitalized Elderly Longitudinal Project. JAMA. 1998;279:371–5.

A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. JAMA. 1995;274:1591–8.

Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, Adrie C, Bollaert P-E, Brun F, et al. Opinions about surrogate designation: a population survey in France. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1711–4.

Rogers J, Ridley S, Chrispin P, Scotton H, Lloyd D. Reliability of the next of kins’ estimates of critically ill patients’ quality of life. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:1137–43.

Scales DC, Tansey CM, Matte A, Herridge MS. Difference in reported pre-morbid health-related quality of life between ARDS survivors and their substitute decision makers. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:1826–31.

Loewy EH. Advance directives. Good, bad or indifferent. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2004;116:411–6.

Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:987–94.

Sprangers MAG, Aaronson NK. The role of health care providers and significant others in evaluating the quality of life of patients with chronic disease: A review. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:743–60.

Hubert S, Wainschtein S, Hugues A, Schimpf C, Degroote T, Tiercelet K, et al. Advance directives in France: do junior general practitioners want to improve their implementation and usage? A nationwide survey. BMC Med Ethics. 2019;20(1):19.

Dowling T, Kennedy S, Foran S. Implementing advance directives-An international literature review of important considerations for nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28:1177–90.

Um S. Vices in autonomous paternalism: The case of advance directives and persons living with dementia1. Bioethics. 2022;36:511–8.

De Vleminck A, Pardon K, Beernaert K, Deschepper R, Houttekier D, Van Audenhove C, et al. Barriers to advance care planning in cancer, heart failure and dementia patients: a focus group study on general practitioners’ views and experiences. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e84905.

Bond CJ, Lowton K. Geriatricians’ views of advance decisions and their use in clinical care in England: qualitative study. Age Ageing. 2011;40:450–6.

Moore N, Detering KM, Low T, Nolte L, Fraser S, Sellars M. Doctors’ perspectives on adhering to advance care directives when making medical decisions for patients: an Australian interview study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e032638.

Pilnick A. Reconsidering patient-centred care: Authority, expertise and abandonment. Health Expect Int J Public Particip Health Care Health Policy. 2023;26:1785–8.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their warm appreciation to the experts of the SFC (Société Française du Cancer/Cancer French Society) and of the SFGM-TC (Société Francophone de Greffe de Moelle et de Thérapie Cellulaire/French-speaking society for bone marrow transplant and cell therapy) for their invaluable assistance in the ethical consideration and design of the survey.

We would also like to thank all the physicians who participated in the dissemination of the study across France, by alphabetical order: Dr Jerôme Barriere, Pr Jacque-Olivier Bay, Dr Cyriac blonz, Dr Delphine Borchiellini, Dr Estelle Botton, Dr Rémi Bourdais, Dr Hélène Boussion, Dr Aurélie Cabanne- Hamy, Dr Brice Chanez, Dr Chakiba -Brugère, Dr Thomas Chevalier, Pr Philippe Colombat, Dr Rémi Fillatre, Dr Anne Floquet, Dr Nicolas Jovenin, Dr Laura Haik , Pr Didier Lacombe, Dr Axel Leysalle, Dr Marie Pierre Liebaert, Pr Didier Mayeur, Dr Emanuel Nicolas, Pr Olivier Penel, Dr Constance Perrot, Pr Ravaud , Dr Colombe Saillard, Dr Julien Schmidt, Dr Florian Scotte, Dr Pauline Soibinet Oudot, Dr Annabelle Stocklin, Pr Eric Terrebonne, Dr Constance Thibault, Dr Philippe Trensz, Dr Youssef Trigui, Dr Armelle Vinceneux, Dr Virginie Woisard.

Finally we would like to thank Dyani Gaudilliere for her patient editing of the final manuscript.

Role of funder

The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was sponsored by the Groupe Hospitalier Paris Saint-Joseph.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, AC, KS, APB, FP, JPL. Methodology: AC, FP, JPL, JOB. Delphi procedure: AC, KS, APB, MM, MC, JOB, CB, JPL, FP, REQUIEM study group and Experts of SFC and SFGM-TC. Design of the questionnaire: AC, KS, APB, MM, MC, JOB, CB, JPL, FP. First draft: AC, KS, FP. review and editing: FP, JPL, CB, JOB and MM, MC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cambriel, A., Serey, K., Pollina-Bachellerie, A. et al. Oncologists’ perspective on advance directives, a French national prospective cross-sectional survey – the ADORE study. BMC Med Ethics 25, 44 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-024-01046-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-024-01046-8