Abstract

Objective

Nursing staff health status is pivotal to healthcare system resilience during global health crises. This study aims to comprehensively evaluate nurses’ mental health profiles, focusing on the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and somatization symptoms and their associations with career development stages, to inform targeted health interventions.

Methods

A cross-sectional assessment of 107 nurses from a tertiary hospital was conducted using validated scales: Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) for anxiety, and Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15) for somatization. Demographic variables included gender, age, education level, professional title, marital status, parenthood, and work experience. Multivariate logistic regression, chi-square tests, and Fisher’s exact test were employed to analyze associations between education, age, professional title, and mental health outcomes.

Results

Most nurses exhibited no significant depression (81.3%) or anxiety (75.7%) symptoms. However, higher education levels (OR = 2.1, p = 0.03) and younger age (OR = 1.9, p = 0.04) were linked to elevated depression and anxiety risks. Somatization symptoms were predominantly mild-to-moderate (68.2%), with professional title significantly correlating with severity (p = 0.01), suggesting career-stage-specific stress impacts physical health.

Conclusion

Career development stages critically influence nurses’ psychological and somatic health. Tailored mental health interventions and occupational support strategies are essential to mitigate stress disparities across career phases, optimize nursing resources, and enhance healthcare efficacy.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global health crisis, particularly the outbreak of COVID-19, has brought unprecedented challenges to healthcare systems worldwide [1, 2]. In this context, as key frontline workers, nursing staff have not only taken on heavy workloads but also faced extremely high occupational risks [3, 4]. Since its emergence in late 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic has persisted for over two years [5]. The continuous emergence of new variants and the recurring waves of the pandemic have greatly impacted the normal lives and health of people globally [6,7,8]. Unlike other countries, China has maintained a zero-tolerance approach to the pandemic, implementing measures such as isolation, lockdowns, and centralized treatment whenever an outbreak occurs [8,9,10]. In this unique work environment, nursing staff, especially nurses, play a crucial role in the effectiveness of pandemic control efforts. Therefore, the health status of nursing staff not only directly affects their personal quality of life and work capacity but also has a profound impact on the quality of patient care and the responsiveness of the healthcare system.

Regular nucleic acid testing is conducted across various regions in China to prevent the spread and recurrence of cases, with comprehensive screening following the emergence of new cases [11]. Additionally, due to the nature of China’s epidemic prevention efforts, local governments often request assistance from neighboring areas when new outbreaks occur, prompting healthcare workers from other regions to provide support in affected areas. Under such circumstances, frontline healthcare workers who endure prolonged work-related stress inevitably face a range of psychological and behavioral issues [12, 13]. It is particularly true for staff in specific departments of tertiary hospitals, where many workers, especially nurses, repeatedly travel to different outbreak zones to offer support, often working under high-pressure conditions for extended periods [14,15,16]. The impact of this unique work environment on their mental health is a significant concern, especially as COVID-19 prevention enters a phase of routine vaccination and nucleic acid testing, presenting new challenges for healthcare workers.

The career development stage plays a crucial role in the mental health of nursing staff. Nursing staff at different career stages face distinct work challenges and sources of stress, affecting their mental health status [17, 18]. Junior nursing staff often encounter high work pressure and lower job security [19], making them more susceptible to anxiety and depression as they adapt to their professional roles [20]. In contrast, mid-level nursing staff may experience burnout and decreased job satisfaction [21], issues linked to increased responsibilities and the bottlenecks in their career progression. Although senior nursing staff may have a higher sense of accomplishment in their careers, they also face greater professional responsibilities and more complex tasks, which pose significant challenges in managing work-related stress and maintaining mental health. Therefore, exploring the relationship between the career development stage and the mental health of nursing staff, particularly the associations among depression, anxiety, and somatization symptoms, is a critical area of current research.

Although existing research has addressed the mental health issues of nursing staff, several limitations remain. First, most studies have focused on specific mental health problems, such as depression or anxiety, with a lack of comprehensive analysis of multiple mental health symptoms [22]. Second, exploring the relationship between the career development stage and mental health in the current literature is relatively fragmented, with no systematic theoretical framework yet established [23]. Additionally, the influence of demographic variables such as age, education level, and marital status on mental health has been debated across different studies [24]. Therefore, systematically investigating these factors’ overall impact on the mental health of nursing staff, particularly in the high-intensity work environment of a tertiary hospital, holds significant practical relevance. This study aims to fill these research gaps by conducting a comprehensive assessment of 107 nursing staff in a tertiary hospital, examining the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and somatization symptoms, and exploring their relationship with the career development stage to provide a more holistic understanding of the mental health of nursing staff.

The core objective of this study is to analyze the mental health profiles of nursing staff, with a focus on the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and somatization symptoms, and to explore their association with career development stages. Using statistical methods including multivariate logistic regression, chi-square tests, and Fisher’s exact test, the study examines how factors such as education level, age, and professional title influence mental health outcomes. The findings provide valuable insights for developing targeted interventions and occupational health strategies to support nurses at different career stages, with important implications for workforce well-being and healthcare quality.

Materials and methods

Study design

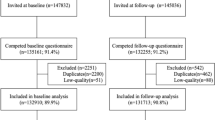

This cross-sectional study was conducted from January 21 to 23, 2021. A convenience sampling method was adopted, and data were collected via an online questionnaire during the designated period. The survey link was distributed to the target population, allowing participants to complete it on any internet-enabled device to enhance accessibility and participation.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) registered nurses currently employed at a tertiary hospital in China; (2) at least one year of work experience; (3) voluntary participation and consent to complete the online questionnaire; and (4) ability to understand and complete the electronic survey.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) non-nursing staff (e.g., administrative or logistics personnel); (2) nursing interns or those who had not yet obtained a nursing license; (3) staff on leave or off-duty during the survey period; and (4) respondents with obviously incomplete or logically inconsistent questionnaires (e.g., identical responses throughout or extreme outliers).

Setting

The survey was conducted in a tertiary hospital in China with the aim of assessing the working environment and job satisfaction of nurses.

Participants and sample size

The target population comprised nurses from the hospital above. A total of 107 valid responses were collected, resulting in a 100% response rate, indicating a high level of engagement and participation among the nursing staff.

Instruments used

Prior to data collection, the required sample size was estimated using GPower 3.1 software [25]. Assuming a medium effect size (effect size = 0.3), a significance level (α) of 0.05, and a statistical power (1 − β) of 0.80, a two-tailed correlation analysis was selected. The minimum required sample size was calculated to be 84 participants. To account for potential invalid responses or missing data, 107 questionnaires were planned for distribution, and all were successfully collected and deemed valid.

Comprehensive evaluation and analysis of mental and physical health among healthcare workers based on a WeChat survey

To ensure the effectiveness and accuracy of this study, we utilized the Questionnaire Star platform to distribute the survey through WeChat groups. First, we thoroughly explained the purpose of the survey and assured participants that all data would be kept strictly confidential to protect their privacy. We requested that all eligible participants voluntarily complete the survey based on their actual experiences to ensure the authenticity of the data and the fairness of the study.

The survey was designed in four parts:

-

1.

General Information: This section collected basic demographic data, including gender, age group, education level, professional title, years of service, and marital and parental status. Additionally, we recorded whether healthcare workers had participated in frontline epidemic prevention efforts, such as assisting in Hubei, supporting infectious disease departments, aiding nucleic acid testing in Jilin Province, participating in hospital outpatient nucleic acid testing, or working in hospital pre-screening and triage. The survey also included detailed questions related to the nucleic acid sampling process, such as whether the household of the sampled individual was under quarantine, whether there were suspected cases, the cooperation level of the sampled individuals, and their awareness of preventive measures.

-

2.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [26]: A 9-item scale for screening depressive symptoms; Cronbach’s α = 0.89 in the original study. Each item is scored from 0 to 3 based on the frequency of the symptoms, where 0 represents “not at all,” 1 represents “several days,” 2 represents “more than half the days,” and 3 represents “nearly every day.” The total score ranges from 0 to 27. Depression symptoms are categorized as follows: scores of 1–4 indicate no depression; 5–9 indicate mild depression; 10–14 indicate moderate depression; 15–19 indicate moderately severe depression; and 20–27 indicate severe depression.

-

3.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) [27]: A 7-item tool for assessing anxiety severity; Cronbach’s α = 0.92, with good validity. Each item is scored from 0 to 3 based on symptom frequency, with 0 indicating “not at all,” 1 indicating “several days,” 2 indicating “more than half the days,” and 3 indicating “nearly every day.” The total score ranges from 0 to 21. Anxiety symptoms are considered present with a score above 4. The levels of anxiety symptoms are categorized as follows: 1–4 indicates no anxiety, 5–9 indicates mild anxiety, 10–14 indicates moderate anxiety, and 15–21 indicates severe anxiety.

-

4.

Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15) [28]: A 15-item measure of somatic symptom severity; Cronbach’s α = 0.80–0.87, effectively identifying somatization. Each item is scored from 0 to 2, where 0 indicates “not at all bothered,” 1 indicates “bothered a little,” and 2 indicates “bothered a lot.” The total score ranges from 0 to 30. The severity of somatic symptoms is categorized as follows: 0–4 indicates minimal symptoms, 5–9 indicates low severity, 10–14 indicates moderate severity, and scores above 14 indicate high severity.

Among the 107 valid questionnaires collected in this study, the internal consistency of the PHQ-9, GAD-7, and PHQ-15 scales was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. The results were as follows: PHQ-9: α = 0.88; GAD-7: α = 0.90; and PHQ-15: α = 0.85, indicating good internal consistency for all three instruments.

To ensure the scientific rigor and applicability of the questionnaire tools, both a pretest and face validity evaluation were conducted prior to the formal survey:

Face Validity: The research team invited three nursing managers with over 10 years of clinical experience and two academic experts in nursing to evaluate the appropriateness, clarity, and relevance of the questionnaire items. All experts agreed that the items adequately covered key dimensions of the work environment and job satisfaction, were worded, and aligned with the language and cognitive habits of nurses. Based on their feedback, several items with ambiguous wording were revised to enhance clarity and comprehensibility.

Pretest Implementation: Before official distribution, a pretest was conducted with 15 representative nurses to assess the feasibility and time required to complete the questionnaire. All participants completed the survey within 10 min without technical or comprehension difficulties. Based on their feedback, minor adjustments were made to improve logical coherence and the overall flow of the questionnaire.

Ethical considerations

This study involved data analysis collected via anonymous self-administered questionnaires and did not include human or animal experimentation; therefore, ethical committee approval was not required. All data collection and analysis procedures were conducted by ethical standards and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were presented with an electronic consent form before completing the questionnaire to ensure informed consent. Participants were informed that their involvement was voluntary and that they could withdraw anytime. Confidentiality and anonymity were maintained throughout the study to protect participants’ privacy and autonomy.

Statistical analysis

To ensure the accuracy and scientific rigor of the survey data, the data processing and analysis were conducted as follows: First, the survey data were exported from the Questionnaire Star platform and then sorted and preliminarily analyzed using SPSS 22.0 software. In the statistical analysis, various chi-square tests were employed to assess the differences in the positivity rates of depression, anxiety, and somatization symptoms across different groups. Specifically, the procedures were as follows: (1) Pearson’s chi-square test was used when all expected frequencies (T) were ≥ 5 and the total sample size (n) was ≥ 40; (2) Continuity correction chi-square test was applied when 1 ≤ T < 5 and n ≥ 40; (3) Fisher’s exact test was utilized when T < 1 or n < 40. Additionally, to explore influencing factors, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all statistical tests.

Results

Analysis of the basic characteristics and pandemic response participation of nursing staff

The survey revealed that most participants were female, with 92 women and 15 men, highlighting the dominance of women in the nursing profession (Fig. 1A). The age distribution showed that most nurses (98 individuals, or 91.6%) were between 26 and 40 years old, indicating that this group forms the backbone of the frontline workforce (Fig. 1B). Regarding educational background, 92.5% of the nurses held a bachelor’s degree, reflecting a high level of education (Fig. 1C). Regarding professional titles, 70.1% were junior nurses, suggesting that most participants were in their careers’ early or mid stages (Fig. 1D). Regarding work experience, 60.7% had 5 to 10 years of experience (Fig. 1E). Concerning family status, 70.1% of the nurses were married (Fig. 1F), and 56.1% had children (Fig. 1G). Notably, 62 nurses had participated in nucleic acid testing support in Hubei Province and other medium-risk areas, demonstrating their active involvement and significant role in public health events (Table 1).

Demographic characteristics and professional background distribution of the nursing staff. Note: (A) Gender distribution, showing the number of male and female nurses participating in the survey; (B) Age group distribution, presented as percentages across different age ranges (20–25 years, 26–30 years, 31–40 years, 41–50 years); (C) Education level distribution, showing the percentage of nurses with the highest education level (high school, undergraduate, graduate); (D) Professional title distribution, reflecting the percentage composition of different professional titles (junior nurse, nurse, senior nurse); (E) Years of work experience distribution, indicating the percentage of nurses with varying lengths of service (less than 5 years, 5–10 years, more than 10 years); (F) Marital status distribution, displaying the percentage of married and single nurses; (G) Distribution of nurses with or without children, shown as percentages

Analysis of the prevalence of depression symptoms among nursing staff and their correlation with education level and age

Among the 107 nurses surveyed, 85 (79.4%) showed no symptoms of depression, 18 (16.8%) had mild depression, and 4 (3.7%) had moderate depression (Fig. 2A and B). The distribution of depression symptoms varied by education level. Nurses with associate, bachelor’s, and master’s degrees exhibited different rates of depressive symptoms, with higher frequencies observed among those with higher education levels (Fig. 2C). Multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that both education level and age group were significantly associated with the presence of depression symptoms (Fig. 2D).

Prevalence of depression symptoms among nursing staff and its relationship with education level. Note: (A) Distribution of 107 nurses classified by levels of depression symptoms, represented by a bar chart showing the number of nurses in each depression category; (B) Percentage distribution of different levels of depression symptoms, illustrated with a bar chart depicting the percentages of no depression, mild depression, and moderate depression, based on PHQ-9 scores; (C) Stacked bar chart showing the proportion of depression symptoms by education level, with education levels categorized as “Associate Degree,” “Bachelor’s Degree,” and “Master’s Degree,” and each depression level represented by different colors to visually display the impact of education level on depression symptom distribution; (D) Coefficient bar chart using a multivariate logistic regression model, displaying the effects of age and education level on depression risk. The bars are color-coded to represent different model variables, such as age groups and education levels, with the estimated coefficients reflecting the strength and direction of the impact. All charts were generated using the ggplot2 package in the R environment, ensuring visual consistency and data accuracy

Analysis of the distribution of anxiety symptoms among nursing staff and their association with educational background and age

A total of 107 nurses completed the GAD-7 assessment. Among them, 90 nurses (84.1%) showed no anxiety symptoms (Fig. 3A), and 14 nurses (13.1%) reported mild anxiety (Fig. 3B). Only one nurse had moderate anxiety, and two had severe anxiety. Regarding educational background, most nurses with a master’s degree did not show anxiety symptoms, although a higher proportion reported mild anxiety. Fisher’s exact test showed no significant association between education level and anxiety symptoms (p = 0.342) (Fig. 3C). Similarly, the distribution of anxiety symptoms across different age groups showed no significant difference (p = 0.7832) (Fig. 3D).

Distribution of anxiety symptoms among nursing staff and their relationship with education level and age. Note: (A) Distribution of 107 nurses classified by levels of anxiety symptoms. Anxiety symptoms are categorized based on GAD-7 total scores into “No Anxiety,” “Mild Anxiety,” “Moderate Anxiety,” and “Severe Anxiety,” with a bar chart representing the number of nurses in each category; (B) Percentage distribution of anxiety levels, visually reflecting the relative frequency of each anxiety level through a bar chart; (C) Stacked bar chart showing the proportion of anxiety symptoms by education level, with education levels categorized as “Associate Degree,” “Bachelor’s Degree,” and “Master’s Degree,” and each anxiety level represented by different colors to illustrate the relationship between education level and anxiety symptoms; (D) Stacked bar chart showing the proportion of anxiety symptoms by age group, with age groups categorized as “20–25 years,” “26–30 years,” “31–40 years,” and “41–50 years,” and each anxiety level represented by different colors to display the relationship between age and anxiety symptoms. All charts were generated using the ggplot2 package in the R environment, ensuring accuracy and consistency in visual representation

The significant impact of professional title on somatization symptoms among nurses and the necessity of occupational stress management

In this study, we used the PHQ-15 questionnaire to assess somatization symptoms among 107 nurses and analyzed their association with different professional titles, educational backgrounds, and personal life circumstances. As shown in Fig. 4A, most nurses exhibited symptoms ranging from none to moderate, with 29 nurses showing minimal symptoms, 47 showing mild symptoms, 23 showing moderate symptoms, and 8 nurses showing severe somatization symptoms. Regarding proportion (Fig. 4B), 92.5% of nurses had mild to moderate symptoms, while severe symptoms were relatively rare, accounting for 7.5% of the total. Further analysis revealed a significant difference in the severity of somatization symptoms across professional titles (Fig. 4C), with professional titles being significantly associated with the severity of these symptoms (X²=21.032, p = 0.002). It suggests that differences in responsibilities and work pressure may be key factors contributing to the variation in somatization symptoms. In contrast, other variables such as marital status (Fig. 4D), gender (Fig. 4E), parental status (Fig. 4F), education level (Fig. 4G), age group (Fig. 4H), and years of work experience (Fig. 4I) did not show statistically significant differences, although some observations were made.

Distribution of somatization symptoms among nurses across professional titles and their association with demographic characteristics. Note: (A) Distribution of 107 nurses classified by levels of somatization symptoms, ranging from no symptoms to severe symptoms, presented in four categories; (B) Percentage distribution of somatization symptoms levels, highlighting the prevalence of mild and moderate symptoms among nurses; (C) Analysis of somatization symptoms by professional title, using Pearson’s chi-square test, which shows a significant difference (X2 = 21.032, p = 0.002), indicating that professional title has a statistically significant impact on somatization symptoms; (D) Distribution of somatization symptoms by marital status, analyzed using Pearson’s chi-square test, which did not show statistical significance (p = 0.4782); (E) Impact of gender on the distribution of somatization symptoms, with chi-square test results not showing statistical significance (p = 0.2113); (F) Distribution of somatization symptoms among nurses with or without children, with chi-square test results showing no significant difference (p = 0.7048); (G) Distribution of somatization symptoms by education level, with a trend that did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.06171), but education level remains a factor of interest; (H) Distribution of somatization symptoms by age group, with statistical test results not reaching significance (p = 0.7895); (I) Distribution of somatization symptoms by years of work experience, with test results showing no significant difference (p = 0.1515). All charts were generated using the ggplot2 package in R software, ensuring consistency and accuracy in data visualization

Discussion

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in late 2019, healthcare systems worldwide have been under unprecedented pressure, particularly for frontline nursing staff who face not only high-intensity workloads but also significant infection risks [29]. In China, as the pandemic prevention and control efforts enter a normalized stage, the mental health of nursing staff has become an urgent concern [30,31,32]. This study found that the majority of nurses did not exhibit significant depression or anxiety symptoms, which contrasts with findings from some previous studies. According to the survey results of 107 nurses from a tertiary hospital, the incidence rates of depression, anxiety, and somatization symptoms were 20.6%, 15.9%, and 72.9%, respectively. The relatively lower rates of depression and anxiety, combined with the higher prevalence of somatization symptoms, suggest that the physical stress from heavy workloads has a greater impact on nursing staff. This finding aligns with the results of Liang et al. [33], indicating that the measures implemented by frontline healthcare workers in China have effectively mitigated mental health issues. However, this does not imply that the mental health challenges faced by nursing staff have been fully resolved, as the study still identified varying degrees of mental health issues among some nurses, highlighting the need for ongoing attention and intervention.

This study found that nurses with higher education levels and younger ages exhibited a greater tendency toward depression and anxiety, consistent with findings from some previous studies [34,35,36]. The research indicates that there are significant differences in the incidence and severity of depression symptoms among nurses with different educational backgrounds. However, there has been limited exploration into whether nurses with higher education levels are more prone to depression symptoms (Fig. 5). We also found that nurses over the age of 26 are more likely to experience depression symptoms compared to those aged 20–25, possibly due to the greater pressure of family responsibilities and the need to take on some managerial tasks at work. Based on these findings, we recommend reducing stress through management policies, psychological support, and human resource protection to safeguard nurses’ mental health. Additionally, it is advised that mental health education be incorporated as a standard component of training programs for responding to public health emergencies.

The significant correlation found in this study between professional title and the severity of somatization symptoms highlights the physical health challenges nursing staff face at different career development stages. Nursing staff with higher professional titles often bear greater responsibilities and manage more complex tasks, which makes them more susceptible to somatization symptoms in a high-pressure work environment. The study also found no significant differences in the incidence of depression, anxiety, and somatization symptoms among nurses who had worked on the front lines, suggesting that China’s mental health management measures for frontline healthcare workers have been effective. However, the study identified two nurses with severe anxiety: one who participated in the Hubei assistance mission and faced delays in sample collection due to language barriers, and another who reported that a lack of public health knowledge and inconsistent community coordination during provincial support efforts led to time wastage during nucleic acid testing. These cases indicate the need to further optimize the coordination and management of nucleic acid testing to reduce the work pressure on frontline nurses, thereby alleviating their somatization symptoms and psychological stress.

This study employed a multivariate logistic regression analysis to systematically explore the impact of demographic variables such as education level, age, and professional title on the mental health of nursing staff [37,38,39]. While similar methods have been widely used in previous research, the unique aspect of this study lies in its simultaneous consideration of multiple mental health indicators—depression, anxiety, and somatization symptoms—and their relationship with career development stages. Compared to studies focusing on a single mental health issue, the comprehensive analysis in this study provides a more holistic understanding of the mental health of nursing staff. Additionally, the study’s findings reveal differences from previous research regarding the influence of demographic variables, such as gender and marital status, on mental health, with varying directions and degrees of impact observed. These discrepancies may be attributed to differences in study populations, cultural contexts, and work environments.

This study found that the career development stage is closely related to the mental health of nursing staff, particularly highlighting the significant association between professional title and somatization symptoms. It suggests that the mechanisms through which stressors at different career stages impact mental health warrant further investigation. Nursing staff with higher professional titles may face greater workloads, more complex decision-making tasks, and stronger professional responsibilities, all of which can increase their psychological burden and exacerbate issues such as anxiety and depression. Conversely, junior nursing staff may experience additional stress due to a lack of experience and incomplete skill development as they adapt to their professional roles, potentially leading to mental health problems. Although previous research has explored these mechanisms to some extent, a systematic theoretical framework has yet to be established. The findings of this study provide new evidence in this area, and it is recommended that future research further investigate the potential mechanisms through which the career development stage influences the mental health of nursing staff.

Based on the findings of this study, several practical applications and policy recommendations are proposed for enhancing the mental health of nursing staff. First, mental health education and support measures should be strengthened in the early stages of career development to help nursing staff better adapt to their professional roles. Second, for nursing staff in the mid-to-late stages of their careers, particularly those with higher professional titles, additional physical health support and career development guidance should be provided to reduce their work-related stress and physical burden. Furthermore, hospital management should establish and refine systems for monitoring and intervening in the mental health of nursing staff, regularly conducting mental health assessments and offering personalized psychological counseling and support services based on the assessment results. These measures can effectively improve the mental health of nursing staff, enhancing the quality of healthcare services.

The findings of this study provide important scientific evidence for healthcare institutions to develop mental health support strategies for nursing staff. It is crucial to consider the impact of professional title and educational background on mental health when planning career development and training programs for nursing staff. Additionally, this study underscores the importance of conducting mental health assessments and providing support for younger nurses to prevent early-career mental health issues from developing into more severe long-term problems.

Limitations

This study systematically investigated the work environment and psychological status of nurses in a tertiary hospital, revealing the association between occupational characteristics and mental health among nursing staff. The findings provide foundational data to support the development of targeted intervention strategies. However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to infer causal relationships between variables. Second, the use of convenience sampling may introduce selection bias and reduce the representativeness of the findings. Third, the sample was drawn from a single tertiary hospital, which restricts the generalizability of the results and may not reflect the mental health status of nurses in other types of healthcare institutions. Additionally, self-reported data on psychological conditions may be subject to reporting bias, as participants might underreport symptoms due to social desirability or privacy concerns.

Recommendations

Future studies could employ longitudinal designs to explore the causal relationships between professional title, education level, and mental health factors. Qualitative methods, such as in-depth interviews or focus groups, may also be introduced to gain deeper insights into nurses’ psychological experiences and sources of stress in real-world clinical settings—insights that go beyond the scope of structured questionnaires. Furthermore, expanding the study to include nurses from different types of healthcare institutions and regions would enhance the generalizability and applicability of the findings. Additional variables, such as job satisfaction and personal life circumstances, should be considered to comprehensively assess factors influencing nurses’ mental health. Ultimately, intervention strategies developed based on these findings will offer a scientific foundation for improving the well-being and work performance of nursing staff.

Conclusion

In summary, this study reveals the psychological and physical health challenges faced by nursing staff throughout their careers. We found that a nurse’s professional title significantly influences the severity of somatization symptoms, likely due to differences in responsibilities and work-related stress. Additionally, nurses with higher education levels are more prone to depression symptoms, suggesting that higher education may bring additional psychological pressure. Furthermore, younger nursing staff exhibit a greater tendency toward depression and anxiety, possibly related to the uncertainty and initial stress of their careers.

Data availability

All data can be provided as needed.

Abbreviations

- GAD-7:

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7

- PHQ-15:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-15

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

References

Martinez-Hollingsworth A, Kim L, Richardson TG, Angulo M, Liu R, Friedman T, et al. Supporting bleeders and billers. J Ambul Care Manage. 2021;44:172–83.

Kyranou M. Setting minimum standards of practice in times of crisis. J Nurs Adm Manag. 2022;30:357–8.

Costa IAP, Nóbrega JF, Bentes CML, Lynn FA, Bentes M do, Souza N. M de L. COVID-19 Nursing Staff Sizing Technology. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing. 2024;42:567–73.

Kennedy MS. The nursing crisis in acute care. AJN Am J Nurs. 2021;121:7–7.

Qu J, Lv X. The response measures to the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8.

Primorac D, Vrdoljak K, Brlek P, Pavelić E, Molnar V, Matišić V et al. Adaptive immune responses and immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Front Immunol. 2022;13.

Forchette L, Sebastian W, Liu T. A comprehensive review of COVID-19 virology, vaccines, variants, and therapeutics. Curr Med Sci. 2021;41:1037–51.

Zhang Y, Zhang H, Zhang W. SARS-CoV-2 variants, immune escape, and countermeasures. Front Med. 2022;16:196–207.

Kombe Kombe AJ, Li B, Zahid A, Mengist HM, Bounda G-A, Zhou Y et al. Epidemiology and burden of human papillomavirus and related diseases, molecular pathogenesis, and vaccine evaluation. Front Public Health. 2021;8.

Chen Y, Zhao X, Zhou H, Zhu H, Jiang S, Wang P. Broadly neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and other human coronaviruses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;23:189–99.

Liang Y, Wu K, Zhou Y, Huang X, Zhou Y, Liu Z. Mental health in frontline medical workers during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease epidemic in China: A comparison with the general population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:6550.

Medby C, Clifford SL, Norquay M, Hansen TK, Gurney J. Management of COVID-19 in a deployed setting. Mil Med. 2021;188:e451–5.

Cai Q, Feng H, Huang J, Wang M, Wang Q, Lu X, et al. The mental health of frontline and non-frontline medical workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: A case-control study. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:210–5.

Teo I, Chay J, Cheung YB, Sung SC, Tewani KG, Yeo LF, et al. Healthcare worker stress, anxiety and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore: A 6-month multi-centre prospective study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0258866.

Xie W, Liu M, Okoli CTC, Zeng L, Huang S, Ye X, et al. Construction and evaluation of a predictive model for compassion fatigue among emergency department nurses: A cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2023;148:104613.

Hsu F-F, Yang C-J, Tsai M-S, Tsai H-Y, Chen H-A, Liao C-H. Control of an outbreak of COVID-19 at a tertiary hospital in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2022;55:1052–9.

Bayuo J, Agbenorku P. Compassion fatigue in the burn unit: A review of quantitative evidence. J Burn Care Res. 2021;43:957–64.

Snyder RL, Barnes LEA, White KA, Cochran RL. Burnout and staff turnover among certified nursing assistants working in acute care hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2023;18:e0290880.

Scanlan JN, Still M, Radican J, Henkel D, Heffernan T, Farrugia P et al. Workplace experiences of mental health consumer peer workers in new South Wales, Australia: a survey study exploring job satisfaction, burnout and turnover intention. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20.

Yip Y-C, Yip K-H, Tsui W-K. The transformational experience of junior nurses resulting from providing care to COVID-19 patients: from facing hurdles to achieving psychological growth. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:7383.

Penconek T, Tate K, Bernardes A, Lee S, Micaroni SPM, Balsanelli AP, et al. Determinants of nurse manager job satisfaction: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;118:103906.

Buselli R, Corsi M, Baldanzi S, Chiumiento M, Del Lupo E, Dell’Oste V, et al. Professional quality of life and mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to Sars-Cov-2 (Covid-19). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:6180.

Hao Q, Wang D, Xie M, Tang Y, Dou Y, Zhu L et al. Prevalence and risk factors of mental health problems among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12.

Robles R, Rodríguez E, Vega-Ramírez H, Álvarez-Icaza D, Madrigal E, Durand S, et al. Mental health problems among healthcare workers involved with the COVID-19 outbreak. Brazilian J Psychiatry. 2021;43:494–503.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang A-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41:1149–60.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:258–66.

Lancashire L, Biggar V, Comer M, Frangiosa T, Gage A, Paulsen R et al. Caring for dementia caregivers: Understanding caregiver stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gerontol Geriatric Med. 2023;9.

Que J, Shi L, Deng J, Liu J, Zhang L, Wu S, et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study in China. Gen Psychiatry. 2020;33:e100259.

Chau JPC, Lo SHS, Zhao J, Butt L, Saran R, Lam SKY, et al. Lessons from the COVID-19 epidemic in Hubei, China: perspectives on frontline nursing. J Infect Prev. 2022;23:206–13.

Irandoost SF, Sedighi S, Hoseini AS, Ahmadi A, Safari H, Ebadi Fard Azar F, et al. Activities and challenges of volunteers in confrontation with COVID-19: A qualitative study in Iran. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022;82:103314.

Liang M, Chen Q, Li Y, et al. Status quo and influencing factors for anxiety, depression, and insomnia among 4 237 nurses in Hunan Province. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2021;46(8):822–30.

Opoku Agyemang S, Ninnoni JP, Enyan NIE. Prevalence and determinants of depression, anxiety and stress among psychiatric nurses in Ghana: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2022;21.

Zhou Y, Wang S, Liu M, Gan G, Qin N, Luo X et al. The role of sleep quality and perceived stress on depressive symptoms among tertiary hospital nurses: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23.

Li Y, Fan R, Lu Y, Li H, Liu X, Kong G, et al. Prevalence of psychological symptoms and associated risk factors among nurses in 30 provinces during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Lancet Reg Health - Western Pac. 2023;30:100618.

Hao X-Y, Guo Y-X, Lou J-S, Cao J-B, Liu M, Mi T-Y, et al. Mental health changes in elderly patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. J Affect Disord. 2023;343:77–85.

Zhang Y, Tao S, Qu Y, Mou X, Gan H, Zhou P et al. The correlation between lifestyle health behaviors, coping style, and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic among college students: two rounds of a web-based study. Front Public Health. 2023;10.

Mao X, Dong W, Zhang J, Zhang F, Deng W, Li Z et al. Mental health status and its associated factors among female nurses in the normalization of COVID-19 epidemic prevention and control in China. Front Public Health. 2023;10.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tiancheng Mo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Collection, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft.Pengju Wang: Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing.Lixin Liu: Resources, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing.Yujiao Wang: Data Collection, Visualization, Project Administration.Rui Wang: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding Acquisition, Writing – Review & Editing, Correspondence.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Clinical Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of Jilin University (No.2024-1121). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study protocol followed the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

All authors agree to its publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mo, T., Wang, P., Liu, L. et al. Career stage variations in mental and somatic health symptoms among nursing professionals in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs 24, 647 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-025-03251-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-025-03251-1