Abstract

Background

The Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC-5As) questionnaire has been designed to evaluate the healthcare experiences of individuals with chronic diseases such as diabetes. Older adults are at higher risk for diabetes and its associated complications. The aim of this study was transcultural adaptation and evaluation of the validity and reliability of the PACIC-5As questionnaire in older patients with diabetes residing in Qazvin City, Iran.

Method

In this validation study, we recruited 306 older patients with diabetes from Comprehensive Health Centers in Qazvin, Iran. The multi-stage cluster sampling technique was used to choose a representative sample. The PACIC-5As questionnaire was translated into Persian using the World Health Organization (WHO) standardized method. The validity (face, content, and construct) and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) of the PACIC-5As were assessed. Data analysis was conducted using R software and the Lavaan package.

Results

The mean age of the older patients was 69.99 ± 6.94 years old. Most older participants were female (n = 180, 58.82%) and married (n = 216, 70.59%). Regarding face validity, all items of PACIC-5As had impact scores greater than 1.5. In terms of content validity, all items had a content validity ratio > 0.49 and a content validity index > 0.79. The results of confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated that the model exhibited satisfactory fit across the expected five factors, including assess, advise, agree, assist, and arrange, for the 25 items of the PACIC-5As questionnaire. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the PACIC-5As questionnaire was 0.805.

Conclusion

This study indicates that the Persian version of the PACIC-5As questionnaire is valid and reliable for assessing healthcare experiences in older patients with diabetes. This means that the questionnaire can be effectively used in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The global population is aging rapidly [1]. The fast growth of older people brings significant challenges, particularly relating to their health [2]. Approximately 75% of individuals aged 60 and above are affected by at least one chronic disease, with nearly 50% experiencing two or more chronic conditions [3]. Diabetes mellitus is among the most common and preventable chronic diseases [4]. The prevalence of diabetes is highest among older adults [5]. Nearly half of all individuals with diabetes are older adults (aged 65 years or older) [6]. The older adult population is one of the fastest-growing segments of the diabetes population. It is projected that these numbers will grow dramatically over the next few decades [7]. In Iran, Rashidi et al. (2017) found that approximately 14.4% of older adults have been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes [8].

Diabetes has emerged as one of the most serious and prevalent chronic diseases, posing a life-threatening risk, debilitating complications, substantial costs, and a reduction in life expectancy [9]. Older adults with diabetes are at serious risk of both micro and macrovascular complications [10]. Diabetes leads to an increased need for healthcare services, home care, hospitalization, and even residency in nursing homes [11]. Since self-care is a crucial aspect of diabetes management, patients need to adopt proper lifestyle habits and gain sufficient knowledge about the disease and its treatments [12].

Appropriate management of diabetes poses a significant challenge for individuals with the condition and healthcare providers [13]. Diabetes in older patients is a significant public health concern in the 21st century, and when combined with other health conditions, it can lead to exacerbated side effects [14]. Furthermore, older adults with diabetes require different types and qualities of care than other patient groups due to physiological, psychological, and social changes [15]. Iran is one of the most populous countries in the Middle East, where diabetes management is currently inadequate. Previous systematic reviews have shown that people aged over 55, especially women, tend to have poorer diabetes management [16]. A nationwide analysis of data for 30,202 patients revealed that only 13.2% of individuals with diabetes successfully attained satisfactory levels of glycemic control [17].

Managing diabetes in this group requires a comprehensive healthcare system that includes diagnosis, monitoring, and continuous medical treatment. The McColl Institute for Health Innovation developed the Chronic Care Model (CCM) to guide the delivery of healthcare services to patients with chronic conditions [18]. The CCM is a conceptual framework designed to bridge the gap between clinical research and real-life medical practice [19]. It focuses on providing proactive and planned care for chronic diseases rather than reactive and unplanned care. The CCM has six key dimensions: organization of health care, clinical information systems, delivery system design, decision support, self-management support, and community resources. It has been widely accepted for improving the care of chronically ill patients. Specifically, the “self-management support” aspect of the CCM helps patients enhance their confidence and skills to manage their illness better [20].

The Patients Assessment Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) questionnaire, developed by Glasgow et al., is used to assess patient care for chronic diseases based on the CCM [21]. It is a self-reporting instrument that provides patients’ perspectives on receiving care for chronic diseases [22]. While there are several tools to measure patients’ experiences of chronic care [23], PACIC is one of the most suitable instruments to measure the chronic care management experiences of patients as it assesses the level of alignment with the CCM [24, 25]. The initial version of the questionnaire comprises 20 items divided into five subscales: patient activation, decision-making support, goal setting, problem-solving, and follow-up [26]. Glasgow et al. [24] expanded the PACIC questionnaire by including six additional items to assess the recommended 5As model of chronic disease care in accordance with the guidelines of the United States Preventive Services Task Force [27]. The “5As” model is an evidence-based approach to behavior change employed to improve patients’ self-management. The primary elements of this model include assessing current behavior (assess), counseling the patient (advise), reaching a shared agreement on realistic goals (agree), assisting the patient throughout the lifestyle change (assist), and providing ongoing follow-up (arrange) [28]. The PACIC-5As model has been adapted into several languages, including Hindi [29], Danish [30], French [31], Korean [32], Thai [33], Bahasa Melayu [34], Arabic [35], German [36], and Spanish [37].

Diabetes incidence has increasingly risen in Iran, especially among the older adults. Several reports consistently highlight that diabetic patients in Iran largely do not receive the necessary quality healthcare services [38]. Due to the significant role of culture and context in perceiving diabetes care [39], it needs for a questionnaire that has acceptable validity, reliability, and cultural appropriateness for older Iranian patients with diabetes. Currently, there is a lack of suitable tools to evaluate the quality of care for chronic diseases in older Iranians. The PACIC-5 A is an invaluable tool for evaluating the structure of primary care and self-management support in diabetes from the patient’s viewpoint. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the validity and reliability of the PACIC-5As instrument in a sample of older patients with diabetes in Qazvin, Iran.

Objectives

The objectives of this study are the following: (1) to translate and to assess the psychometric quality of the PACIC using the appropriate psychometric tests; (2) to determine the relationship between PACIC-5As scores and older patient characteristics and the quality of diabetes-specific care received.

Methods

This validation study was carried out on 306 older patients referred to the health centers in Qazvin, Iran. The multi-stage cluster sampling method was performed for selecting the older patients. For this purpose, Qazvin City was divided into three urban zones. Then, nine Comprehensive Health Centers randomly selected from the zones (three from the first, four from the second, and two from the third zone). In each center, a certain number of older patients with diabetes were randomly identified, and they were then called for the initial screening. During the phone call, potential participants were provided with an explanation of the study’s purpose and procedures. Older patients who met the inclusion criteria were invited to come to the health centers near the region where they resided, at a certain time. The questionnaires were completed through face-to-face interviews by the first author.

Inclusion criteria were being 60 years old or over a diagnosis of diabetes for at least six months (by a specialist physician), and willingness to participate in the study. Older patients with severe physical or mental problems that hindered their ability to communicate were excluded from the study.

In Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) studies, one way to determine sample size is to use the Rule of Thumb, which recommends having at least ten participants for each item in the questionnaire. It also suggests that sample sizes larger than 300 participants are generally considered suitable for most structural models in confirmatory factor analysis [38]. As a result, 306 participants were chosen for this study.

Instruments

Data were collected using a demographic and clinical characteristics checklist and the PACIC-5As questionnaire.

The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics checklist elicited information from older patients that included age, gender, marital status, education level, occupation, economic status, living arrangement, duration of diabetes, type of diabetes treatment, and diabetes-related complications.

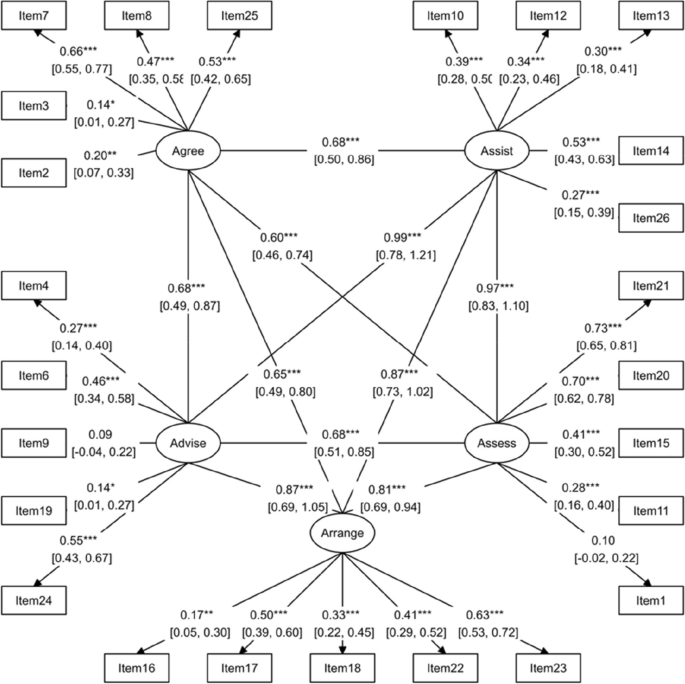

PACIC-5As questionnaire: The PACIC questionnaire consists of 20 items and five domains of assessment (items 1, 11, 15, 20, 21), advise (items 4, 6, 9, 19, 24), agree (items 2, 3, 7, 8, 25), assist (items 10, 12, 13, 14, 26), and arrange (items 16, 17, 18, 22, 23). The questionnaire items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “never” with a score of 1 to “always” with a score of 5, where a higher score indicates better patient assessment of chronic illness care [24].

Translation process

After correspondence with the questionnaire designer and obtaining permission, the translation process was conducted according to the protocols of the World Health Organization (WHO) [40] as follows:

Translation of the questionnaire into Persian

Two individuals who are proficient in both English and Persian independently translated the English version of the questionnaire into Persian. One of the translators had familiarity with medical sciences and their terminology. Ultimately, we obtained two independent Persian translations of the PACIC-5As.

In the second stage, the Persian translation of the questionnaire and revised by the project executors and colleagues. They took into account all options for word or phrase equivalency to prepare a unified Persian version of the questionnaire.

Retranslation into English

In this stage, two additional translators, fluent in both languages, translated the Persian version back into English. Then, the final English version was compared to the original questionnaire by two separate translators, and minor translation errors were found and fixed.

Validity of the questionnaire

The face, content, and structural validity of the questionnaire were examined.

Face validity assessment

For quantitative face validity, 10 older individuals with diabetes were asked to rate the importance of each item in the questionnaire on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not important at all) to 5 (very important). The impact scores were calculated using the following formula:

The term “frequency” refers to the percentage of individuals who rated the item with scores of 4 or 5, while “importance” represents the average importance rating based on the Likert scale.

The item impact score should not be less than 1.5 to accept the face validity of each item. Only questions with item impact scores higher than 1.5 are considered acceptable in terms of face validity [41]. The impact scores of all items of PACIC-5As were greater than 1.5 (Table 1).

Content validity assessment

Both qualitative and quantitative methods were used to determine the validity of the content.

For qualitative assessment, the questionnaire was provided to 15 experts in geriatric medicine, geriatric nursing, nursing education, and endocrinology. They were asked to review the questionnaire based on criteria such as adherence to grammar rules, using appropriate terminology and proper phrases, and providing necessary feedback.

In the quantitative method for determining content validity, the content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI) were calculated.

To determine the CVR, experts were initially requested to review each item based on a 3-point Likert scale (1. not essential, 2. useful but not essential, 3. essential). Then, the CVR was calculated using the following formula:

In the above formula, “ne” represents the number of experts who rated the item as “essential,” and “N” represents the total number of experts [42].

If the resulting value from the formula is greater than the critical value from the Lawshe table (which is 0.49, determined based on the evaluation of 15 experts), it indicates that the presence of the corresponding item is statistically significant (p < 0.05) and necessary in this instrument [43].

The CVI was used to determine the relevance of the questionnaire items. The questionnaire was given to 15 experts, who rated each statement on a 4-point Likert scale (1. not relevant at all, 2. somewhat relevant, 3. moderately relevant, 4. completely relevant). The CVI score was then calculated by adding up the scores for each item rated 3 or 4, and dividing by the total number of respondents. According to the guidelines, items with scores above 0.79 were kept in the questionnaire. Items with scores between 0.70 and 0.79 were considered borderline and needed to be revised, and items scoring less than 0.70 were considered unacceptable and should be removed [44]. The CVR and I-CVI for the items of PACIC-5As are presented in Table 1.

Construct validity assessment

Structural validity assessment

To determine the number of factors in the scale, CFA was performed using common goodness-of-fit indices in Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with R software and the Lavaan package.

Reliability

To assess the reliability and internal consistency of the questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used. An internal consistency above 0.70 is considered acceptable [45].

Ethical consideration

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran (IR.QUMS.REC.1401.148). Participants were informed about the objectives, procedures, potential benefits, and drawbacks of the study. They were instructed that participation was voluntary and that the confidentiality of the obtained information was guaranteed. Informed consent was obtained from all respondents.

Data analysis

R software version 4.2.2 and the Lavaan package were used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics such as mean and standard deviation were used to describe quantitative variables, including age, duration of diabetes, and PACIC-5As scores. Frequency and percentage were utilized to describe qualitative variables, including gender, marital status, education level, occupation, economic status, living arrangement, type of diabetes treatment, and diabetes-related complications. In the CFA model, the most common goodness-of-fit indices were used to assess the fit of the proposed model based on an acceptable threshold obtained through maximum likelihood estimation. The reliability and internal consistency of the questionnaire were assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The multivariate regression model was used to determine the predictors of older patients’ perspective of diabetic care. Normal distribution of the data was confirmed by the skewness (0.078) and the kurtosis (4.329) values that were in the acceptable ranges. As Byrne (2010) [46] stated that if the skewness value is between − 2 to + 2 and the kurtosis value is between − 7 to + 7, normality of the data could be assumed. The multicollinearity issues was assessed by the variance inflation factor (VIF) and none of variables had VIF more than 5. The homoscedasticity was also evaluated and confirmed. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 69.99 ± 6.94 years, ranging from 60 to 96 years. The average age of diabetes onset was 12.46 ± 5.9 years. Most older patients (n = 230, 75.16%) were utilizing insulin injections as part of their treatment regimen. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the older patients are presented in Table 2.

Based on the information in Table 3, the mean score of PACIC-5 A was 3.47 ± 0.24. The highest level was in advice (4.13 ± 0.30) and the lowest level was in arrange (3.21 ± 0.30).

The multivariate regression model showed that level of education was the significant predictor of older patients’ perspective of diabetic care; older patients had a better perspective if they had secondary and diploma (β = 0.11, p = 0.003) or academic (β: 0.23, p < 0.001) educational level (Table 4).

CFA results

Based on the information in Table 5, the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis of the proposed model yielded a reasonable fit, with a Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) of 0.07 and a chi-squared/df ratio of 2.539, both indicating acceptable model fit [47]. The Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI) of 0.85 and Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI) of 0.81 suggest a moderately good fit, while the Incremental Fit Index (IFI) of 0.72 and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) of 0.71 slightly fall below the recommended threshold of 0.90 for good fit. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) of 0.08 is within the acceptable range of less than 0.08, further supporting the overall reasonable fit of the SEM model. The structural model of the questionnaire is presented in Fig. 1.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the PACIC-5As questionnaire in older adults with diabetes. The study also sought to establish the correlation between PACIC-5As scores and the characteristics of older patients, as well as the quality of diabetes-specific care received by older adults with diabetes in Qazvin, Iran. The study found that the mean scores on the PACIC-5As and its domains were higher than 3.0, which is similar to scores found in diabetes patients in the USA [22], Germany [48], and Switzerland [49]. This suggests that older Iranian patients receive a reasonable level of patient-centered care in accordance with the CCM.

The level of education was found to be a significant predictor of older patients’ perspective on diabetic care. Patients with higher education levels had higher PACIC-5As scores. Likewise, Rajabpour et al. (2019) [50] reported that patients with higher education had a greater perception of holistic care. Zakeri-moghadam and Sadeghi (2013) [51] also discovered a direct and significant relationship between patients’ education levels and their satisfaction with nursing services. This result may be attributed to the higher expectations of less educated patients from the healthcare staff and their care, and their lesser adaptation to their existing condition.

The CFA results confirmed the presence of five factors, which are assess, advise, agree, assist, and arrange, for the 25 items of the PACIC-5As questionnaire. Glasgow et al. (2005), the developers of the questionnaire, also confirmed the presence of these five factors based on the CMC model for patients with one or multiple chronic diseases [22]. Similarly, Wensing et al. (2008) [25] confirmed the existence of these five factors in Dutch patients with diabetes or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) for the PACIC or PACIC-5 A questionnaire. Additionally, Shah et al. (2008) [37] verified the same for diabetic patients, and Rosemann et al. (2007) [20] for patients with osteoarthritis. However, Drewes et al. (2012) [52] could not replicate the five-factor structure in diabetic patients and long-term care patients. Similarly, Schwenke et al. (2019) [36] did not find the five-factor structure for the PACIC-5 A questionnaire among obese patients. These contradictory results may be due to methodological differences and the specific characteristics of the study samples. The statistical methods used in the studies were quite different, and those that conducted the EFA used various methods to determine the number of factors. For instance, Drewes et al. (2012) [52] focused on patients with multiple chronic conditions and employed both EFA and CFA using the split-half method. They used three types of EFA (Principal axis factoring, PAF) with oblimin rotation, parallel analysis (PA), and Velicer’s minimum average partial (MAP) test] to explore the factor structure of the data. On the other hand, Schwenke et al. (2019) [36] examined the perspective of obese patients and used EFA with PA and the eigenvalue criterion and scree plot.

The reliability of the instrument in our study, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha, was in the acceptable range (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.805). In a study by Glasgow et al. (2005) [22], a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.96 for PACIC and 0.97 for PACIC-5As was reported in diabetic patients. Schwenke et al. (2019) [36] also reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93 for PACIC and 0.94 for PACIC-5As in obese patients. Additionally, Alharbi et al. (2016) [35] found a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93 for PACIC and 0.90 for PACIC-5As. The findings from previous studies demonstrated an optimal level of internal consistency. The variation in Cronbach’s alpha values in these studies may be attributed to the differences in the sample being investigated.

Limitations

Since this study was conducted on older patients with diabetes, the results may not be generalizable to older individuals with other chronic diseases. Another limitation is the response bias, including social desirability bias that seems relevant to the geriatric population. To mitigate this limitation, we provided necessary explanations regarding the study’s objectives and the application of the results to improve the care of patients with diabetes. Another limitation of the current research is the lack of test-retest reliability assessment due to limited access to the study’s older participants. It is recommended that future studies examine the temporal stability of the assessment tool.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicated that the PACIC-5As is a reliable and valid tool for measuring quality of care based on the key components of the CCM and patient motivation using the “5 A” principles in older Iranian patients with diabetes. This tool can also evaluate how well physicians’ counseling reflects the 5 A-approach, which involves assessing, advising, agreeing, assisting, and arranging. Using this instrument can guide health professionals and policy-makers in Iran to improve the healthcare delivery system for older diabetic patients and enhance their satisfaction with the care they receive. In the present study, the 5As analysis showed that the scores obtained from “Arrange” and “Assiste” were less than the other “As” among older patients. So, it is suggested to use practical and cost-effective interventions for improving older patients’ perspective on diabetic care.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PACIC-5As:

-

Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- Chronic Care Model:

-

CCM

- US:

-

United State

- CVR:

-

Content Validity Ratio

- CVI:

-

Content Validity Index

- CFA:

-

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

- SEM:

-

Structural Equation Modeling

- VIF:

-

Variance Inflation Factor

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- IQR:

-

Interquartile Range

- RMSEA:

-

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

- GFI:

-

Goodness of Fit

- AGFI:

-

Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index

- IFI:

-

Incremental Fit Index

- CFI:

-

Comparative Fit Index

- SRMR:

-

Standardized Root Mean Square Residual

References

Rashedi V, Asadi-Lari M, Foroughan M, Delbari A, Fadayevatan R. Prevalence of disability in Iranian older adults in Tehran, Iran: a population-based study. J Health Social Sci. 2016;1(3):251–62.

Motalebi SA, Zajkani Z, Mohammadi F, Habibi M, Mafi M, Ranjkesh F. Effect of acupressure on dynamic balance in elderly women: a randomized controlled trial. Exp Aging Res. 2020;46(5):433–45.

Hosseini SR, Moslehi A, Hamidian SM, Taghian SA. The relation between chronic diseases and disability in elderly of Amirkola. Salmand. 2014;9(2):80–7.

Naqshbandi M, Harris SB, Esler JG, Antwi-Nsiah F. Global complication rates of type 2 diabetes in indigenous peoples: a comprehensive review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;82(1):1–17.

Das U, Kar N. Prevalence and risk factor of diabetes among the elderly people in West Bengal: evidence-based LASI 1st wave. BMC Endocr Disorders. 2023;23(1):170.

Bellary S, Kyrou I, Brown JE, Bailey CJ. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in older adults: clinical considerations and management. Nat Reviews Endocrinol. 2021;17(9):534–48.

Kalyani RR, Golden SH, Cefalu WT. Diabetes and aging: unique considerations and goals of care. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(4):440.

Rashedi V, Asadi-Lari M, Delbari A, Fadayevatan R, Borhaninejad V, Foroughan M. Prevalence of diabetes type 2 in older adults: findings from a large population-based survey in Tehran, Iran (Urban HEART-2). Diabetes Metabolic Syndrome: Clin Res Reviews. 2017;11:S347–50.

Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109119.

Zhang Y, Wieffer H, Modha R, Balar B, Pollack M, Krishnarajah G. ORIGINAL RESEARCH the Burden of Hypoglycemia in Type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of patient and economic perspectives. JCOM-Journal Clin Outcomes Manage. 2010;17(12):547.

Sinclair A, Morley JE, Rodriguez-Mañas L, Paolisso G, Bayer T, Zeyfang A, et al. Diabetes mellitus in older people: position statement on behalf of the International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics (IAGG), the European Diabetes Working Party for older people (EDWPOP), and the International Task Force of experts in diabetes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(6):497–502.

Tessier DM, Lassmann-Vague V. Diabetes and education in the elderly. Diabetes Metab. 2007;33:S75–8.

Epakchipoor F, Bastani F, Pashaei SF. Self-management and medication adherence in older adults with type II diabetes referring to the endocrinology clinics of the teaching hospital affiliated to Iran University of Medical Sciences (2019). Iran J Nurs. 2021;34(129):1–14.

Roopa K, Rama Devi G. Quality of life of elderly diabetic and hypertensive people-impact of intervention programme. IOSR J Hum Soc Sci. 2014;19(3):67–73.

Araban M. Quality of midwifery care provided to women admitted for delivery in selected hospitals of Yazd. J Nurs Midwifery Quarterly-Shaheed Beheshti Univ Med Sci Health Serv. 2013;23(81):19–26.

Noshad S, Afarideh M, Heidari B, Mechanick JI, Esteghamati A. Diabetes care in Iran: where we stand and where we are headed. Annals Global Health. 2015;81(6):839–50.

Esteghamati A, Larijani B, Aghajani MH, Ghaemi F, Kermanchi J, Shahrami A, et al. Diabetes in Iran: prospective analysis from first nationwide diabetes report of National Program for Prevention and Control of Diabetes (NPPCD-2016). Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):13461.

Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff. 2001;20(6):64–78.

Lenfant C. Clinical research to clinical practice—lost in translation? N Engl J Med. 2003;349(9):868–74.

Rosemann T, Laux G, Droesemeyer S, Gensichen J, Szecsenyi J. Evaluation of a culturally adapted German version of the Patient Assessment of chronic illness care (PACIC 5A) questionnaire in a sample of osteoarthritis patients. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13(5):806–13.

Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry SJ, Wagner EH. Collaborative management of chronic illness. American College of Physicians; 1997. pp. 1097–102.

Glasgow RE, Whitesides H, Nelson CC, King DK. Use of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) with diabetic patients: relationship to patient characteristics, receipt of care, and self-management. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(11):2655–61.

Vrijhoef HJ, Berbee R, Wagner EH, Steuten LM. Quality of integrated chronic care measured by patient survey: identification, selection and application of most appropriate instruments. Health Expect. 2009;12(4):417–29.

Glasgow RE, Wagner EH, Schaefer J, Mahoney LD, Reid RJ, Greene SM. Development and validation of the patient assessment of chronic illness care (PACIC). Med Care. 2005;43(5):436–44.

Wensing M, van Lieshout J, Jung HP, Hermsen J, Rosemann T. The patients Assessment Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) questionnaire in the Netherlands: a validation study in rural general practice. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:1–6.

Chiu H-C, Hsieh H-M, Lin Y-C, Kuo S-J, Kao H-Y, Yeh S-CJ, et al. Patient assessment of diabetes care in a pay-for-performance program. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(2):183–90.

Whitlock EP, Orleans CT, Pender N, Allan J. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: an evidence-based approach. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(4):267–84.

Vallis M, Piccinini–Vallis H, Sharma AM, Freedhoff Y. Modified 5 as: minimal intervention for obesity counseling in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59(1):27–31.

Koley M, Saha S, Ghosh S, Nag G, Kundu M, Mondal R, et al. Patient-assessed chronic illness care (PACIC) scenario in an Indian homeopathic hospital. J Traditional Complement Med. 2016;6(1):72–7.

Maindal HT, Sokolowski I, Vedsted P. Adaptation, data quality and confirmatory factor analysis of the Danish version of the PACIC questionnaire. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22(1):31–6.

Krucien N, Le Vaillant M, Pelletier-Fleury N. Adaptation and validation of the patient assessment of chronic illness care in the French context. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:1–12.

Rick J, Rowe K, Hann M, Sibbald B, Reeves D, Roland M, et al. Psychometric properties of the patient assessment of chronic illness care measure: acceptability, reliability and validity in United Kingdom patients with long-term conditions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:1–15.

Zeugfang D, Wisetborisut A, Angkurawaranon C, Aramrattana A, Wensing M, Szecsenyi J, et al. Translation and validation of the PACIC + questionnaire: the Thai version. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19:1–10.

Abdul-Razak S, Ramli AS, Badlishah-Sham SF, Haniff J. Validity and reliability of the patient assessment on chronic illness care (PACIC) questionnaire: the malay version. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19:1–11.

Alharbi NS, Alotaibi M, de Lusignan S. An analysis of health policies designed to control and prevent diabetes in Saudi Arabia. Glob J Health Sci. 2016;8(11):233.

Schwenke M, Welzel FD, Luck-Sikorski C, Pabst A, Kersting A, Blüher M, et al. Psychometric properties of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care measure (PACIC-5A) among patients with obesity. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:1–12.

Shah NR, Aragones A, Schaefer EW, Stevens D, Gourevitch MN, Glasgow RE. Peer reviewed: validation of the Spanish translation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) Survey. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(4).

Mohseni M, Shams Ghoreishi T, Houshmandi S, Moosavi A, Azami-Aghdash S, Asgarlou Z. Challenges of managing diabetes in Iran: meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:1–12.

Sachdeva S, Khalique N, Ansari MA, Khan Z, Mishra SK, Sharma G. Cultural determinants: addressing barriers to holistic diabetes care. J Social Health Diabetes. 2015;3(01):033–8.

World Health Organization. Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. 2016. http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/.

Hajizadeh E, Asghari M. Statistical methods and analyses in health and biosciences: a methodological approach. Tehran, Iran: Iranian Student Book Agency; 2011.

DeVon HA, Block ME, Moyle-Wright P, Ernst DM, Hayden SJ, Lazzara DJ, et al. A psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39(2):155–64.

Lawshe C. A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Pschycology. 1975;28:563–75.

Yaghmaie F. Content validity and its estimation. J Med Educ. 2003;3(1).

Atkinson G, Nevill AM. Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. Sports Med. 1998;26:217–38.

Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts, applications, and programming (multivariate applications series). New York: Taylor & Francis Group. 2010;396(1):7384.

Rosemann T, Laux G, Szecsenyi J, Grol R. The Chronic Care Model: congruency and predictors among primary care patients with osteoarthritis. BMJ Qual Saf. 2008;17(6):442–6.

Frei A, Senn O, Huber F, Vecellio M, Steurer J, Woitzek K, et al. Congruency of diabetes care with the Chronic Care Model in different Swiss health care organisations from the patients’ perspective: a cross sectional study. Swiss Med Wkly. 2014;144(3536):w13992–w.

Szecsenyi J, Rosemann T, Joos S, Peters-Klimm F, Miksch A. German diabetes disease management programs are appropriate for restructuring care according to the chronic care model: an evaluation with the patient assessment of chronic illness care instrument. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(6):1150–4.

Rajabpour S, Rayyani M, Mangolian shahrbabaki P. The relationship between Iranian patients’ perception of holistic care and satisfaction with nursing care. BMC Nurs. 2019;18:1–7.

Sadeghi S, Kazemnejad A. Effects of comprehensive-care program on patients’ satisfaction with trauma in emergency department. Iran J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;2(3):54–62.

Drewes HW, de Jong-van Til JT, Struijs JN, Baan CA, Tekle FB, Meijboom BR et al. Measuring chronic care management experience of patients with diabetes: PACIC and PACIC + validation. Int J Integr care. 2012;12.

Acknowledgements

This research is part of the SM thesis in geriatric nursing. The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude and appreciation to the Research Deputy of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences and all the older patients who participated in this study for their cooperation and contribution.

Funding

This article was extracted from a student thesis in geriatric nursing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M, SA.M, and L.D conceived and designed the research method and helped to draft the manuscript. S.M collected the data. A.A performed the statistical analysis. S.M, SA.M, L.D, and M.A revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences (IR.QUMS.REC.1401.148). Prior to the study, a general overview of the objectives was provided to the older patients. All participants were assured that their information would remain confidential. Informed consent has been obtained from the participants, their parents and legally authorized representatives in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maroufi, S., Dehghankar, L., Alizadeh, A. et al. Transcultural adaptation and validation of Persian Version of Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC-5As) Questionnaire in Iranian older patients with type 2 diabetes. BMC Health Serv Res 24, 1073 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11557-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11557-0