Abstract

Background

Accurate human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2) assessment is critical for guiding breast cancer (BC) treatment. Circulating tumor cells (CTCs), which detach from the primary or secondary tumors and circulate through the bloodstream, can colonize distant sites to form metastases. Previous studies have demonstrated the clinical validity of CTCs as prognostic biomarkers in metastatic breast cancer (mBC). Liquid biopsy testing offers a non-invasive alternative for real-time evaluation of HER2 expression on CTCs, overcoming limitations of repeated histological sampling.

Methods

This study employed a pipeline combining EpCAM-independent enrichment with Parsortix® and immunofluorescence (IF)-based HER2 characterization to assess HER2 expression in patient-derived CTCs from sixteen patients with mBC and compared it to the FDA-approved CellSearch® system and to the HER2 tissue status. CTC detection rates, median CTC counts per 7.5 mL blood, and the fraction of HER2-positive CTCs per sample were determined, and CTC versus tissue status was compared to assess concordance.

Results

The two methods had a strong positive correlation in CTC counts, with the label-free workflow showing a higher CTC detection (100% versus 77% samples with ≥ 1 CTC). Median total CTC counts per 7.5 mL blood were 16.5 (range 3–65) for Parsortix® and 3 (range 1–245) for CellSearch®. Despite a different HER2-positive CTC detection rate (38% versus 11% using Parsortix® and CellSearch®, respectively), both methods showed concordance with the tissue, with the distribution of HER2-positive CTCs reflecting the HER2 status of the biopsy. Patients with HER2-positive mBC showed a higher proportion of HER2-positive CTCs compared to patients with HER2-negative tissue both with Parsortix (55% versus 33%) and with CellSearch (61% versus 1%). No differences in HER2-positive CTC distribution were observed between patients with HER2-low and HER2-zero tumors.

Conclusion

These results support the clinical utility of HER2 assessment on CTCs with both workflows and highlight the potential diagnostic value of label-free CTC enrichment combined with HER2 quantification. Further studies in larger cohorts should be conducted to validate our findings and investigate the clinical relevance of HER2-positive CTCs detected with the developed pipeline, particularly in the context of anti-HER2 therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most diagnosed malignancy and the leading cause of cancer-related death among women worldwide, largely due to its inter- and intra-tumor heterogeneity, unpredictable behavior, and ability to metastasize and develop treatment resistance [1]. BCs are classified into subtypes based on hormone receptors (HR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression, which are determined by the tissue’s histopathology characterization [1,2,3]. Based on current guidelines, HER2 status is assessed using immunohistochemistry (IHC) and in situ hybridization (ISH) on tissue biopsies [4], providing critical guidance for anti-HER2 therapies decisions. However, tissue biopsies are limited due to their invasive nature and inability to fully capture the intra-tumor heterogeneity and dynamic changes in HER2 expression [5]. Overcoming these challenges, liquid biopsies provide a non-invasive and informative alternative for molecular disease characterization by analyzing circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and circulating tumor cells (CTCs) [6]. CTCs, shed from the primary or metastatic sites into the bloodstream, are a powerful tool for real-time assessment of molecular features, such as HER2 expression, and offer informative insights into tumor biology, disease progression, and treatment response [7,8,9]. Several studies established the clinical validity of CTC enumeration as a prognostic biomarker in metastatic breast cancer (mBC); using the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved CTC isolation platform, CellSearch®, a threshold of ≥ 5 CTCs per 7.5 mL of blood has been defined for prognostic stratification in mBC patients, predicting a poor outcome [10,11,12].

Beyond enumeration, studies have evaluated the value of HER2 characterization on CTCs as both a prognostic and predictive biomarker [13, 14]. Among patients screened for the DETECT III and IV trials, 15% of those initially diagnosed with HER2-negative mBC based on IHC tissue analysis had ≥ 1 HER2-positive CTC detected using the CellSearch® platform, which was associated with unfavorable prognosis [8].

Notably, the DETECT III trial provided the first demonstration of clinical utility of HER2 assessment on CTCs, demonstrating improved overall survival in patients with HER2-negative mBC – but HER2-positive CTCs – who were treated with lapatinib [15]. However, in the DETECT III trial, CTCs were evaluated using the CellSearch® platform, which relies on positive epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) expression for identification [16], excluding an important subpopulation of CTCs with low or no EpCAM expression. Notably, CTCs with low or no EpCAM expression may result from epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), or partial EMT (pEMT), which is associated with a highly aggressive metastatic subpopulation [17]. Thus, EpCAM-dependent platforms may exclude a highly aggressive CTC subpopulation characterized by low or no EpCAM expression, thereby compromising detection sensitivity and recovery accuracy [18]. To avoid these limitations, several EpCAM-independent technologies are available for enhancing CTC detection [19], including the Parsortix® system, which was recently cleared by the FDA for use in patients with mBC. Parsortix® leverages cell size and deformability to recover CTCs in an EpCAM-independent fashion, and recovered CTCs are viable for diverse downstream analyses, including HER2 evaluation [20,21,22,23].

In this study, we employed a pipeline combining EpCAM-independent enrichment with Parsortix® and immunofluorescence (IF)-based HER2 characterization to assess HER2 expression in patient-derived CTCs and compared it with the corresponding tissue HER2 status and with the CellSearch®, the gold-standard for CTC analysis, in an exploratory cohort of patients with mBC.

Materials and methods

The overall study design is summarized in Fig. 1 which provides a schematic representation of the experimental workflow.

Study experimental design. (A) Evaluation of the workflow using SKBR3 BC cell line spike-in experiments (B) Pilot study performed on 16 liquid biopsy samples collected from patients with mBC and processed with the EpCAM-independent pipeline. A standard test was conducted in parallel with CellSearch® for clinical practice. Parsortix® image sourced from https://angleplc.com/parsortix-technology/

Cell lines

Human BC SKBR3 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM Corning®, NY, USA). The media was supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, Corning®) and the cells were maintained in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. SKBR3 cells were purchased from ATCC in 2022, authenticated by performing short tandem repeat (STR) profiling using PowerPlex 16 HS (Promega Corporation, WI, USA) and confirmed to be mycoplasma-free.

Spike-in experiments

The analytical validity of the refined EpCAM-free pipeline was confirmed with spike-in experiments using the SKBR3 human BC cell line. Cells were detached from the culture flask with 0.025% trypsin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 100 SKBR3 cells were directly spiked into 7.5 mL of healthy donor blood (HDB) collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes (K2-EDTA BD Vacutainer, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

CTC enrichment: Parsortix®

Spiked-in HDB samples or clinical samples (7.5 mL) collected in EDTA tubes were transferred into a 50 mL polypropylene tube (Corning™ Falcon Conical Centrifuge Tubes, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and loaded into the Parsortix® instrument (Parsortix® PR1 Cell Separation System, ANGLE plc, Guildford, UK) for enrichment. Sample processing was performed using the PX2_S99F program in conjunction with a 6.5 μm Cell Separation Cassette (ANGLE plc, Guildford, Surrey, UK), which captures cells based on size and deformability, per the manufacturer’s protocol. Once the cells were enriched, the flow direction inside the cassette was inverted and the cells trapped in the cassette were washed out with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Enriched cells were harvested in a 1.5 mL Protein LoBind Tube (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany).

Immunofluorescence staining

The enriched fraction collected from Parsortix® was washed with a Running Buffer (RB) containing PBS with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Boehringer Mannheim, Kircheim, Germany) and 2 mM EDTA (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). All cells were stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies directed against surface and intracellular markers (Table 1). Following a blocking step with Human TruStain FcX™, Fc Receptor Blocking Solution (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), for 5 min, antibodies against CD45, EpCAM and HER2 were incubated at room temperature according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Table 1). The cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 20 min at room temperature, permeabilized using Inside Perm (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany) for 10 min and stained with an antibody against CK. Finally, nuclei were stained with 1 µg/mL Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 10 min at room temperature. Each antibody was previously tested in duplicate on the BC cell lines and healthy donor (HD) peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (Supplementary methods).

Slide mounting and imaging

After staining, cells were washed and then resuspended in 15 µL of RB and transferred to the center of a glass slide inside a 1 cm circle, drawn with a hydrophobic barrier pen. The slides were dried for 20 min in the dark at room temperature, mounted using 10 µL of ProLong™ Diamond Antifade Mountant media (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) and allowed to cure overnight in the dark at 4 °C. Slides were imaged using a Zeiss Axio Imager.Z1 fluorescence motorized microscope equipped with an AxioCam MRc camera. Tumor cells were manually identified by a single operator using the following criteria: (1) nucleated cells exhibiting morphological features consistent with tumor cells, such as increased size and distinct nuclear characteristics, and (2) negative immunoreactivity for the leukocyte marker CD45. While positive staining for epithelial markers EpCAM/CK or HER2 was considered supportive in identifying CTCs, it was not required. Identification was primarily based on cellular morphology and CD45 negativity. Given that some CTCs may lose their epithelial characteristics, and that many CTCs are HER2-negative, cells lacking the EpCAM/CK or HER2 markers were not excluded if they met the core criteria. Identified tumor cells and some white blood cells were imaged with the same exposure time for consistency using the AxioVision 4.8 imaging Platform (Carl Zeiss, White Plains, NY, USA).

HER2 expression measurements

HER2 expression on identified cells was quantified as described in the supplementary materials (Supplementary methods, Supplementary Fig. 1). Tumor cells were categorized into high, intermediate, or low/none HER2 expression categories (Supplementary Fig. 2) and PBMCs were excluded from the tumor cell population based on positive CD45 expression.

Clinical samples processing

Sixteen blood samples were collected from a study cohort of 14 patients diagnosed with mBC who were prospectively enrolled in an institutional academic study at Weill Cornell Medicine (New York, NY) between November 2023 and June 2024. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Weill Cornell Medicine (IRB# 1603017108), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The research adhered to the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committees, as well as the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Peripheral blood (7.5 mL) was drawn into EDTA tubes (K2-EDTA BD Vacutainer, Becton Dickinson), samples were stored at room temperature and processed within one hour for CTC enrichment using Parsortix®, and CTC identification and HER2 expression quantification as described above (Sects. CTC enrichment: Parsortix® to HER2 expression measurements). An additional aliquot from each sample was collected in CellSave Preservative Tubes (Menarini Silicon Biosystems, Bryn Athyn, PA, USA) and shipped for CellSearch® (Menarini Silicon Biosystems) clinical testing in a CLIA-certified laboratory, per clinical practice.

Statistical analyses

All data were subjected to statistical analysis to assess significance depending on the case: Chi-squared test, two-way ANOVA, two-tailed Wilcoxon signed-rank test, Spearman’s Rho test and Mann-Whitney test. Tests were performed with GraphPad Software (San Diego, CA, USA), * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Results

Evaluation of the workflow using SKBR3 BC cell line

Before analyzing blood samples from patients, the pipeline including enrichment, staining, and HER2 characterization was tested with spike-in experiments using a HER2-positive breast cancer cell line (SKBR3). 100 SKBR3 cells were spiked into 7.5 mL of HDB in triplicate. A non-spiked HDB sample served as the negative control. The samples were processed through the Parsortix® system and stained using our established IF protocol, yielding clear tumor cell staining with Hoechst 33342-labeled nuclei and distinct visualization of CD45, EpCAM/CK, and HER2 protein expression (Fig. 2A). Protein expression from the IF images was quantified based on intensity (Supplementary methods, Supplementary Fig. 1) and compared to previously established HER2 intensity measurements representing high, intermediate, and no HER2 expression (Supplementary methods, Supplementary Fig. 2 C). Across the three independent replicates, a total of 165 SKBR3 cells (cells positive for hoechst and epithelial markers, and negative for CD45) were identified (43, 62, and 60 cells per replicate, with an average recovery rate of 55%). The HER2 intensity on each cell was then measured and categorized as HER2-high, -intermediate, and -low/none. As expected, the vast majority of SKBR3 (90.20 ± 4.54%) were classified as HER2-positive (intermediate or high, 41, 55, 52 per replicate), with 87.60 ± 3.81% exhibiting high HER2 expression (39, 55, 50 per replicate) (Fig. 2B). No CD45-, EpCAM/CK+, cells were detected in the negative control.

HER2 expression analysis in spiked SKBR3 BC cell lines. (A) IF images of SKBR3 cells and PBMCs recovered from HDB, either spiked with SKBR3 cells (left) or non-spiked (right). Blood was processed using the EpCAM-independent pipeline. Spike-in experiments were conducted in triplicate. The recovered cells were stained for DAPI (blue), CD45 (red), EpCAM/CK (green) and HER2 (cyan) markers. The majority of recovered SKBR3 cells were DAPI+, CD45-, EpCAM/CK+, and HER2+, whereas the majority of cells recovered from the non-spiked HDB blood were DAPI+, CD45+, EpCAM/CK-, and HER2- (B) Comparative bar chart showing the HER2 expression levels (high, intermediate, and low/none) established on the recovered SKBR3 cells using the EpCAM-independent pipeline.

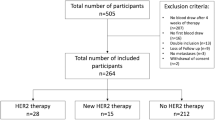

Patients’ characteristics

Sixteen blood samples were collected from a study cohort of 14 patients diagnosed with mBC at the following timepoints: 5 at baseline (31%), 4 at progression (25%) and 7 at restaging (44%) (Table 2). The median age at collection was 48.6 years; twelve patients (86%) had invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), whereas two patients (14%) had invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC). According to tumoral tissue IHC, the cohort included: five patients (36%) with HER2-positive tumors, four (28%) with HR-positive/HER2-negative disease, and five (36%) with triple-negative BC (TNBC). Among the nine patients with HER2-negative tissue expression, three patients (21%) had HER2-zero tumors (IHC score 0), while the remaining six patients (43%) had HER2-low tumors (IHC score 1 + or 2 + without ERBB2 amplification on ISH).

CTC enumeration and HER2 expression quantification with the EpCAM-independent pipeline

Using the EpCAM-independent pipeline, we identified and imaged CTCs based on size and protein expression. Immune cells captured alongside CTCs in the images were removed based on positive CD45 expression. We identified CTCs in all 16 samples, totaling 411 CTCs (Fig. 3A). The median count of CTCs per sample was 16.5 CTCs (IQR 10–46.5). In 11/16 samples (69%), we observed both single CTCs and CTC clusters, ranging from 3 to 10 cells per cluster. Some of the clusters exhibited cells with varying degrees of HER2 expression, underlying the HER2 expression intra-tumor heterogeneity (Fig. 3B). HER2-positive CTCs (defined as intermediate or high HER2 expression) were detected in all samples, accounting for 38% (158/411) of the total CTCs (Fig. 3C). The median HER2-positive CTC count per sample was 9 (IQR 4.5–12.75). The EpCAM-independent pipeline allowed further categorization of HER2-positive CTCs into high and intermediate expression levels: 78% (123/158) exhibited high HER2 expression and 22% (35/158) showed intermediate expression.

HER2 expression status established in patients with mBC by the EpCAM-independent pipeline. (A) Diagram summarizing the CTC count and the HER2 assessment results collected from 16 samples with mBC (B) Representative images of EpCAM/CK+, HER2-positive (top) and HER2-negative (bottom) CTC clusters recovered from patient P3 and P15, respectively (C) Comparative bar chart showing HER2 expression quantification on the identified CTCS on 16 mBC samples as compared to the HER2 status on Tissue (D) Comparative box plots showing HER2-positive CTCs enumeration across the HER2 positive and the HER2 negative patients. Error bars indicate standard deviation. The p value was determined by Mann-Whitney test (*: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ****: p < 0.0001, ns: non-significant) (E) Representative images of EpCAM/CK-low/none expression, and HER2-intermediate (top) and HER2-high (bottom) CTCs recovered from patients P3 and P9, respectively. + and ^ denote separate samples collected from the same patient at different timepoints.

We then compared the level of HER2 expression on CTCs according to tissue HER2 status and identified a higher percentage of HER2-positive CTCs in the HER2-positive BC cohort compared to the HER2-negative BC cohort: 55% (57/104) versus 33% (101/307), respectively; (Chi-square test: p = 0.0017) (Table 3). Among the HER2-positive CTCs, high HER2 expression was detected in 95% of CTCs collected from patients with HER2-positive BC, versus 68% of CTCs collected from patients with HER2-negative tissue (Table 3). Moreover, the median percentage of HER2-positive CTCs per sample was 67% (IQR 52–85%) in patients with HER2-positive tissue status and 33% (IQR 20–69%) in patients with HER2-negative tissue status (Mann-Whitney test: p = 0.04136; Fig. 3D).

Within the HER2-negative BC cohort, no difference was observed in the overall proportion of HER2-positive CTCs between patients with HER2-zero and HER2-low BC (35% versus 32%, respectively) (Table 3), nor in the median percentage of HER2-positive CTCs per sample (31% vs. 33% in HER2-low and HER2-zero, respectively), although statistical testing was limited by the small sample size.

Notably, 83 of the identified cells had low/negative EpCAM/CK expression, which would have likely been missed using EpCAM-dependent enrichment technologies. Ten of these (12%) CTCs were HER2-positive; six with intermediate HER2 expression and four with high HER2 expression (Fig. 3E).

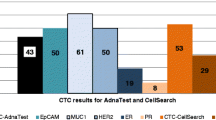

CTC enumeration and HER2 expression quantification with CellSearch ®

All samples reported were processed in parallel with CellSearch® by clinical practice testing. Of the 16 CellSearch® tests performed, data from three samples were unavailable due to low blood volume, unsuccessful CTC enrichment, or delayed processing that compromised sample integrity. Among the 13 evaluable samples, CellSearch® detected 368 CTCs across 10 CTC-positive samples, with 67% of the identified CTCs from a single patient (Fig. 4A). The median number of CTCs per sample was 3 (IQR 0.5–23.5), compared to the median of CTCs collected with the EpCAM-independent pipeline (16.5 CTCs, IQR 10–46.5; Wilcoxon test: p value = 0.0232; Fig. 4B). There was a strong positive correlation between the number of CTCs detected with the two methods (Spearman’s Rho test: r = 0.82804, p = 0.00047). Among the 13 comparable samples, the EpCAM-independent pipeline detected more CTCs in 12 samples (92%) while CellSearch® detected more CTCs in one sample (8%, CTCs detected by Parsortix® and CellSearch® were 58 and 245, respectively). Similarly, more HER2-positive CTCs were detected with Parsortix® compared to CellSearch®, which identified HER2-positive CTCs in only 3 of the 13 evaluable samples (23%). Among all detected CTCs, 11% (40/368) were categorized as HER2-positive by CellSearch® compared to 38% (158/411) with Parsortix® (Chi-square test: p < 0.0001). The median count of HER2-positive CTCs per sample was 0 (IQR 0–2) with CellSearch® versus 9 (IQR 4.5–12.75) with Parsortix® (Wilcoxon test: p = 0.00104). Despite the lower overall detection rate of HER2-positive CTCs by CellSearch®, there was a concordant trend between the two methodologies when compared to HER2 tissue status: the HER2-positive CTC detection was higher in HER2-positive BC patients than in those with HER2-low or HER2-zero BC (61%, 0% and 1%, respectively) (Table 4; Fig. 4C). Among the CTCs recovered by CellSearch®, a median of 52% (IQR 11–91%) were HER2-positive from HER2-positive patients, whereas 0% were HER2-positive from HER2-negative patients. Similar to the findings with the EpCAM-independent pipeline, the CellSearch® platform also showed comparable median percentages of HER2-positive CTCs per sample in patients from the HER2-low and HER2-zero subgroups (0% versus 1.2%, respectively).

Performance of the EpCAM-independent pipeline and CellSearch. (A) Comparative line plot showing CTCs enumeration on 16 mBC patients processed by the Parsortix® (red dots) and CellSearch (blue squares) (B) Comparative box plot demonstrating the CTC enumeration by using Parsortix® (red) versus CellSearch (blue). Error bars indicate standard deviation. The p value was determined by Wilcoxon test (*: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ****: p < 0.0001, ns: non-significant) (C) Comparisons of HER2 assessment on CTCs collected from patients with mBC processed in parallel with the 2 workflows. CTCs were stratified according to their HER2 expression categories (high, intermediate, or low/none) and compared to respective HER2 tissue status. + and ^ denote separate samples collected from the same patient at different timepoints.

Discussion

We present results from an EpCAM-independent pipeline for quantitative assessment of HER2 expression on CTCs, highlighting its potential for longitudinal monitoring of HER2 dynamics in patients with mBC through liquid biopsy.

Although HER2 expression is historically associated with poor prognosis, the development of highly effective HER2-targeted therapies has significantly improved patient outcomes, establishing HER2 as a positive predictive biomarker for BC [24,25,26]. This study demonstrates the feasibility of integrating EpCAM-independent CTC enrichment with HER2 expression quantification and assessment, offering a promising approach for real-time, non-invasive HER2 evaluation. This could enhance treatment planning and monitoring, as current methods for tracking HER2 expression – relying on invasive tissue biopsies – fail to capture the heterogeneity or dynamic evolution of mBC over time [13, 27, 28].

There is growing evidence that CTCs can be used as a comprehensive tool to monitor early biological signs of disease progression [29, 30], thereby aiding in treatment decision-making [28, 31]. HER2 scoring on CTCs using the CellSearch platform was introduced by Riethdorf et al. [32], which established a standardized method for evaluating HER2 expression and demonstrated both the feasibility and clinical relevance of monitoring HER2 status in CTCs. Recently, the DETECT III study introduced the feasibility of HER2 assessment on CTCs captured using CellSearch® and suggested that patients with HER2-negative tissue, but HER2-positive CTCs, may benefit from anti-HER2 therapies [15].

Notably, implementing CTC characterization in clinical practice has been hampered mainly by their limited detection (~ 50% of patients with mBC have ≥ 5 CTCs/7.5 mL of blood, with CellSearch®) [10] and by the lack of methodological standardization [33]. To increase CTC detection rates, we utilized the EpCAM-independent Parsortix® platform in our pipeline, allowing for label-independent enrichment [20]. In our established pipeline, we recovered an average of 55% of the spiked SKBR3 cells, with some cells lost during capture because of variations in their size or deformability, and during processing and washing steps. This loss is similarly described by Sajdik et al., where they captured an average of 59.9% of the spiked SKBR3 after Parsortix® enrichment, with results ranging from 55.4 to 74.4% [34]. Older publications have also investigated the recovery rate of SKBR3 BC cell lines using the CellSearch® platform [35, 36], where the mean recovery rates varied from 47% to 70% and ranged from 5.3% to 114%. All cited studies highlight inter-assay variability driven by cell line, experimental protocol, and processing conditions contributing to recovery rates. Our findings agree with previous reports, which highlight higher CTC recovery rates from Parsortix® compared to CellSearch®. For example, Xu et al. compared CTC yields from Parsortix® and CellSearch® in 7 prostate cancer patient samples, showing that Parsortix® recovered significantly more CTCs (32.1 ± 29.1) compared to CellSearch® (10.1 ± 9.3) in all samples except for one (p = 0.04) [37]. Another study also found higher recovery with Parsortix® versus CellSearch® in 12 patients with small cell lung cancer [38]. In our study, the use of Parsortix® allowed the detection of CTCs in 100% of patients, which would significantly increase their applicability in clinical studies. Importantly, one patient showed a higher CTC recovery with CellSearch®, suggesting that this EpCAM-independent pipeline might miss CTCs which are small, highly deformable, or challenging to segment using image analysis programs.

While other studies have compared the CTC detection performance of CellSearch® and Parsortix®, this is the first study to compare the evaluation of HER2 expression on CTCs by using these two technologies. A higher number of HER2-positive CTCs per sample were detected when using Parsortix®, in line with the overall higher CTC recovery. Importantly, despite the difference in recovery, in both cases the distribution of HER2-positive CTCs varied according to HER2 tissue status, with higher proportions of HER2-positive CTCs per sample among patients with HER2-positive versus HER2-negative mBC, supporting their clinical validity irrespective of the method used. These results align with previous studies that reported a higher prevalence of HER2-positive CTCs in HER2-positive BC cohorts, as compared to the HER2-negative counterparts, irrespective of the technologies used for CTCs enrichment and HER2 assessment [39, 40].

Interestingly, Parsortix® enabled the detection of a markedly higher proportion of HER2-positive CTCs in patients with HER2-negative tissue results, including those classified as HER2-zero tissue (32–35% of HER2-positive CTCs from Parsortix® versus 1% from CellSearch). Previous studies have reported HER2-positive CTCs in patients with HER2-negative tissue [15, 41]; this discordance highlights the intra-tumoral heterogeneity and the dynamic nature of tumor cell populations. Notably, the detection of HER2-positive CTCs in patients with HER2-negative tissue may have important clinical implications, as recently suggested by the results of the DETECT III trial in which patients with HER2-negative mBC but HER2-positive CTCs treated with anti-HER2 treatment showed an improved survival, potentially broadening the cohort eligible for HER2-targeted therapies [15]. In direct comparison of the two pipelines, we found that employing a more sensitive detection technology can reveal a higher proportion of HER2-positive CTCs, even among patients with HER2-negative tissue. This finding may have therapeutic implications, particularly in the context of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), although further validation in prospective clinical studies with larger study cohorts is required to confirm this prospect.

Recently, HER2-low has emerged as a distinct subgroup within HER2-negative breast cancers, defined by low levels of HER2 expression in tissue [42, 43]. This subgroup has gained clinical relevance with the advent of ADCs, a new generation of anti-HER2 therapies that specifically target low HER2-expressing tumors [44, 45]. Despite the promising therapeutic development, our analysis revealed no difference in the detection of HER2-positive CTCs between patients with HER2-low and HER2-zero IHC BC across both pipelines, agreeing with a previous study from Nicolo` et al. [40]. This finding suggests that HER2-positive CTCs alone may be insufficient for distinguishing between HER2-low and HER2-zero IHC BC. However, the limited sample size may also contribute to this lack of differentiation.

Both pipelines were able to differentiate between HER2-intermediate and HER2-high expression on CTCs. In contrast, we could not clearly discriminate between CTCs with no versus low HER2 expression, which were consistently merged into a single group. Thus, these findings and limitations underscore the need for improved detection strategies and larger-scale, prospective clinical trials to improve patient stratification, monitor dynamic changes in CTC HER2 expression during treatment, and optimize treatment selection, particularly in the context of emerging HER2-targeted ADCs [46], including trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) [45].

This study presents several strengths and limitations. As mentioned, this is the first study directly comparing HER2 expression on CTCs with HER2 tissue status (including HER2-low), by using two different CTC-enrichment technologies and including HER2 automated quantification. Moreover, this EpCAM-independent pipeline identified CTCs with low/negative EpCAM/CK expression in 12/16 patient samples and, notably, 12% of these CTCs were also HER2-positive, supporting their malignant nature. This subpopulation, which would be missed by EpCAM-dependent technologies, is particularly important as previous studies showed that CTC populations with low or no EpCAM expression, characteristic of EMT, are usually correlated with a higher disease aggressiveness, invasiveness [18, 47], and resistance to therapies [48]. Finally, the workflow presented in the study demonstrates strong potential for clinical implementation. Leveraging the FDA-cleared Parsortix® system, which enables label-free enrichment of CTCs, combined with automated IF-based quantification, the approach ensures a reliable and reproducible analysis. The entire workflow can be completed within a few days, offering rapid turnaround suitable for clinical decision-making. Compared to the next generation sequencing (NGS)-based circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analyses, this workflow is less complex, more cost-effective, and scalable for broad clinical adoption. In addition, CTCs provide information at the protein level that is not captured by ctDNA testing. Overall, combining CTC assessment with ctDNA could provide a more comprehensive picture of the molecular and phenotypic characteristics of the tumor, which could be serially reassessed over time for a dynamic monitoring of the tumor’s evolution and progression, potentially improving its clinical management.

It is important to acknowledge that this study assessed only a small cohort of patient samples (n = 16), which limits its translatability and generalizability across all mBC patients and although we observe a high detection rate of HER2-positive CTCs in all patients using Parsortix®, their clinical significance remains to be determined. Larger studies and subsequent clinical trials are necessary to confirm these preliminary findings and their clinical implications. Moreover, this study did not evaluate the correlation between HER2 expression on CTCs and patient response to therapy or clinical outcomes. While this represents an important and clinically relevant question, it was considered beyond the scope of the current investigation. Future studies are warranted to explore this relationship in depth, as such analyses will be critical for determining the clinical significance of these preliminary findings and clarifying the role of CTC HER2 expression in guiding treatment decisions and improving outcomes in mBC.

The EpCAM-independent pipeline is semi-automated, relying on operator-based identification of CTCs. While operator-based identification of CTCs is standard for the field, it introduces subjectivity and depends on the operator’s familiarity with tumor cell morphology. Image segmentation algorithms assist in detecting cells in images to measure tumor cell protein expression, but are limited by microscope image quality and may miss extremely small or large CTCs. Balancing automation with expert oversight is essential to ensure consistent and accurate cell measurements. Future workflow iterations should aim to reduce operator intervention by implementing whole-slide scanning rather than capturing individual images. Enhancing automated cell segmentation – potentially through machine learning algorithms trained on manually annotated CTC images – could further improve accuracy and eliminate bias.

Currently, the workflow does not offer sufficient resolution to reliably distinguish between CTCs with absent versus low HER2 expression, an important distinction with potential clinical implications. Additionally, due to overlapping fluorescence filters, it cannot distinguish between CK and EpCAM signals. Future improvements, such as integrating advanced microscopy, applying machine learning models, and fully automating the workflow, may enhance our ability to differentiate these CTC phenotypes more accurately.

Conclusion

CTCs offer a powerful, non-invasive means to track the dynamic evolution of HER2 expression. With HER2 increasingly viewed as a continuum [49], and novel anti-HER2 ADCs showing efficacy even in tumors with minimal HER2 expression [44, 45, 50], characterizing CTCs can help clinicians pinpoint candidates for anti-HER2 therapies and monitor their responsiveness over time. This EpCAM-independent pipeline enhances label-independent CTC detection and enables highly specific, reproducible quantification of HER2 expression. To fully understand the clinical impact of HER2 on CTCs, particularly in cases with low HER2 expression [44], future studies with larger cohorts are essential. Achieving this will require standardized methods for HER2 evaluation on CTCs. Finally, it is important to underline that the pipeline used in this study is adaptable and can be easily extended to assess other biomarkers, broadening its utility beyond HER2 analysis.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors (N.B. and L.S.M.A.), upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACCEPT:

-

Automated CTC classification enumeration phenotyping

- ADC:

-

Antibody-drug conjugates

- a.u:

-

Arbitrary units

- BC:

-

Breast cancer

- BSA:

-

Bovine serum albumin

- CTCs:

-

Circulating tumor cells

- ctDNA:

-

Circulating tumor DNA

- Cy5:

-

Cyanine 5

- EDTA:

-

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- EMT:

-

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

- EpCAM:

-

Epithelial cell adhesion molecule

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- FDA:

-

Food and drug administration

- FITC:

-

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- HD:

-

Healthy donor

- HDB:

-

Healthy donor blood

- HER2:

-

Human epidermal growth factor2

- HR:

-

Horm1 receptor

- IBC:

-

Inflammatory breast cancer

- IDC:

-

Invasive ductal carcinoma

- IF:

-

Immunofluorescence

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- ILC:

-

Invasive lobular carcinoma

- ISH:

-

In situ hybridization

- mBC:

-

Metastatic breast cancer

- N/A:

-

Not applicable

- PBMCs:

-

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- pEMT:

-

Partial epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- PFA:

-

Paraformaldehyde

- RB:

-

Running buffer

- STD:

-

Standard deviation

- T-DXd:

-

Trastuzumab deruxtecan

- TRITC:

-

Tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate

References

Nolan E, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE. Deciphering breast cancer: from biology to the clinic. Cell. 2023;186(8):1708–28.

Tsang JYS, Tse GM. Molecular classification of breast cancer. Adv Anat Pathol. 2020;27(1):27–35.

Rakha EA, Chmielik E, Schmitt FC, Tan PH, Quinn CM, Gallagy G. Assessment of predictive biomarkers in breast cancer: challenges and updates. Pathobiology. 2022;89(5):263–77.

Wolff AC, Hammond MEH, Allison KH, Harvey BE, Mangu PB, Bartlett JMS, et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American society of clinical oncology/college of American pathologists clinical practice guideline focused update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142(11):1364–82.

De Rose F, Meduri B, De Santis MC, Ferro A, Marino L, Colciago RR, et al. Rethinking breast cancer follow-up based on individual risk and recurrence management. Cancer Treat Rev. 2022;109:102434.

Banys-Paluchowski M, Fehm TN, Grimm-Glang D, Rody A, Krawczyk N. Liquid biopsy in metastatic breast cancer: current role of circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor DNA. Oncol Res Treat. 2022;45(1–2):4–11.

Cristofanilli M, Hayes DF, Budd GT, Ellis MJ, Stopeck A, Reuben JM, et al. Circulating tumor cells: a novel prognostic factor for newly diagnosed metastatic breast cancer. JCO. 2005;23(7):1420–30.

Müller V, Banys-Paluchowski M, Friedl TWP, Fasching PA, Schneeweiss A, Hartkopf A, et al. Prognostic relevance of the HER2 status of circulating tumor cells in metastatic breast cancer patients screened for participation in the DETECT study program. ESMO Open. 2021;6(6):100299.

Lee JS, Magbanua MJM, Park JW. Circulating tumor cells in breast cancer: applications in personalized medicine. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;160(3):411–24.

Cristofanilli M, Pierga JY, Reuben J, Rademaker A, Davis AA, Peeters DJ, et al. The clinical use of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) enumeration for staging of metastatic breast cancer (MBC): international expert consensus paper. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;134:39–45.

Bidard FC, Peeters DJ, Fehm T, Nolé F, Gisbert-Criado R, Mavroudis D, et al. Clinical validity of circulating tumour cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(4):406–14.

Banys-Paluchowski M, Krawczyk N, Fehm T. Potential role of circulating tumor cell detection and monitoring in breast cancer: a review of current evidence. Front Oncol. 2016;6:255.

Beije N, Onstenk W, Kraan J, Sieuwerts AM, Hamberg P, Dirix LY, et al. Prognostic impact of HER2 and ER status of circulating tumor cells in metastatic breast cancer patients with a HER2-negative primary tumor. Neoplasia. 2016;18(11):647–53.

Pestrin M, Bessi S, Puglisi F, Minisini AM, Masci G, Battelli N, et al. Final results of a multicenter phase II clinical trial evaluating the activity of single-agent lapatinib in patients with HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer and HER2-positive circulating tumor cells. A proof-of-concept study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(1):283–9.

Fehm T, Mueller V, Banys-Paluchowski M, Fasching PA, Friedl TWP, Hartkopf A, et al. Efficacy of lapatinib in patients with HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer and HER2-positive circulating tumor cells—the DETECT III clinical trial. Clin Chem. 2024;70(1):307–18.

Andree KC, Van Dalum G, Terstappen LWMM. Challenges in circulating tumor cell detection by the CellSearch system. Mol Oncol. 2016;10(3):395–407.

Yu M, Bardia A, Wittner BS, Stott SL, Smas ME, Ting DT, et al. Circulating breast tumor cells exhibit dynamic changes in epithelial and mesenchymal composition. Science. 2013;339(6119):580–4.

Thege FI, Gruber CN, Cardle II, Cong SH, Lannin TB, Kirby BJ. Anti-EGFR capture mitigates EMT- and chemoresistance-associated heterogeneity in a resistance-profiling CTC platform. Anal Biochem. 2019;577:26–33.

Rushton AJ, Nteliopoulos G, Shaw JA, Coombes RC. A review of circulating tumour cell enrichment technologies. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(5):970.

Templeman A, Miller MC, Cooke MJ, O’Shannessy DJ, Gurung Y, Pereira T, et al. Analytical performance of the FDA-cleared Parsortix® PC1 system. J Circ Biomark. 2023;12:26–33.

Miller MC, Robinson PS, Wagner C, O’Shannessy DJ. The parsortix™ cell separation system—a versatile liquid biopsy platform. Cytometry A. 2018;93(12):1234–9.

Cohen EN, Jayachandran G, Moore RG, Cristofanilli M, Lang JE, Khoury JD, et al. A multi-center clinical study to harvest and characterize circulating tumor cells from patients with metastatic breast cancer using the Parsortix® PC1 system. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(21):5238.

Topa J, Grešner P, Żaczek AJ, Markiewicz A. Breast cancer circulating tumor cells with mesenchymal features—an unreachable target? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022;79(2):81.

Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/Neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235(4785):177–82.

Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(11):783–92.

Swain SM, Miles D, Kim SB, Im YH, Im SA, Semiglazov V, et al. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (CLEOPATRA): end-of-study results from a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(4):519–30.

Ignatiadis M, Rothé F, Chaboteaux C, Durbecq V, Rouas G, Criscitiello C, et al. HER2-positive circulating tumor cells in breast cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e15624.

Fehm T, Müller V, Aktas B, Janni W, Schneeweiss A, Stickeler E, et al. HER2 status of circulating tumor cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a prospective, multicenter trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;124(2):403–12.

Andreopoulou E, Yang L-Y, Rangel KM, Reuben JM, Hsu L, Krishnamurthy S, et al. Comparison of assay methods for detection of Circulating tumor cells in metastatic breast cancer: AdnaGen adnatest breastcancer Select/Detect™ versus Veridex CellSearch™ system. Intl J Cancer. 2012;130(7):1590–7.

Shuai Y, Ma Z, Ju J, Wei T, Gao S, Kang Y, et al. Liquid-based biomarkers in breast cancer: looking beyond the blood. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):809.

Munoz-Arcos LS, Nicolò E, Serafini MS, Gerratana L, Reduzzi C, Cristofanilli M. Chapter One - Latest advances in clinical studies of circulating tumor cells in early and metastatic breast cancer. In: Reduzzi C, Gerratana L, Cristofanilli M, editors. International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology [Internet]. Academic Press; 2023 [cited 2025 Sept 17]. pp. 1–21. (Circulating Tumor Cells, From Biotech Innovation to Clinical Utility; vol. 381). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1937644823001193

Riethdorf S, Müller V, Zhang L, Rau T, Loibl S, Komor M, et al. Detection and HER2 expression of circulating tumor cells: prospective monitoring in breast cancer patients treated in the neoadjuvant GeparQuattro trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(9):2634–45.

Vasseur A, Kiavue N, Bidard F, Pierga J, Cabel L. Clinical utility of circulating tumor cells: an update. Mol Oncol. 2021;15(6):1647–66.

Sajdik C, Schuster E, Holzer B, Krainer M, Deutschmann C, Peter S, et al. Comparison of microfluidic platforms for the enrichment of circulating tumor cells in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022;196(1):75–85.

Punnoose EA, Atwal SK, Spoerke JM, Savage H, Pandita A, Yeh RF et al. Molecular Biomarker Analyses Using Circulating Tumor Cells. Santos J, editor. PLoS ONE. 2010 Sept 8;5(9):e12517.

Kallergi G, Politaki E, Alkahtani S, Stournaras C, Georgoulias V. Evaluation of isolation methods for circulating tumor cells (CTCs). Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;40(3–4):411–9.

Xu L, Mao X, Imrali A, Syed F, Mutsvangwa K, Berney D et al. Optimization and Evaluation of a Novel Size Based Circulating Tumor Cell Isolation System. Wu MH, editor. PLoS ONE. 2015 Sept 23;10(9):e0138032.

Chudziak J, Burt DJ, Mohan S, Rothwell DG, Mesquita B, Antonello J, et al. Clinical evaluation of a novel microfluidic device for epitope-independent enrichment of circulating tumour cells in patients with small cell lung cancer. Analyst. 2016;141(2):669–78.

Di Cosimo S, De Marco C, Silvestri M, Busico A, Vingiani A, Pruneri G et al. Chapter Two - Can we define breast cancer HER2 status by liquid biopsy? In: Reduzzi C, Gerratana L, Cristofanilli M, editors. International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology [Internet]. Academic Press; 2023 [cited 2025 Sept 17]. pp. 23–56. (Circulating Tumor Cells, From Biotech Innovation to Clinical Utility; vol. 381). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S193764482300117X

Nicolò E, Serafini MS, Munoz-Arcos L, Pontolillo L, Molteni E, Bayou N, et al. Real-time assessment of HER2 status in circulating tumor cells of breast cancer patients: methods of detection and clinical implications. The Journal of Liquid Biopsy. 2023;2:100117.

Tretschock LM, Clemente H, Smetanay K, Fremd C, Thewes V, Haßdenteufel K, et al. HER2(-low) expression on circulating tumor cells and corresponding metastatic tissue in metastatic breast cancer. Oncol Res Treat. 2024;48(4):161–73.

Schettini F, Chic N, Brasó-Maristany F, Paré L, Pascual T, Conte B, et al. Clinical, pathological, and PAM50 gene expression features of HER2-low breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2021;7(1):1.

Denkert C, Seither F, Schneeweiss A, Link T, Blohmer JU, Just M, et al. Clinical and molecular characteristics of HER2-low-positive breast cancer: pooled analysis of individual patient data from four prospective, neoadjuvant clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(8):1151–61.

Modi S, Jacot W, Yamashita T, Sohn J, Vidal M, Tokunaga E, et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-Low advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022 July;7(1):9–20.

Mosele F, Deluche E, Lusque A, Le Bescond L, Filleron T, Pradat Y, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in metastatic breast cancer with variable HER2 expression: the phase 2 DAISY trial. Nat Med. 2023;29(8):2110–20.

D’Amico P, Reduzzi C, Qiang W, Zhang Y, Gerratana L, Zhang Q, et al. Single-cells isolation and molecular analysis: focus on HER2-Low CTCs in metastatic breast cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021;14(1):79.

Lüönd F, Sugiyama N, Bill R, Bornes L, Hager C, Tang F, et al. Distinct contributions of partial and full EMT to breast cancer malignancy. Dev Cell. 2021;56(23):3203–e322111.

Hashemi M, Arani HZ, Orouei S, Fallah S, Ghorbani A, Khaledabadi M, et al. EMT mechanism in breast cancer metastasis and drug resistance: revisiting molecular interactions and biological functions. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;155:113774.

Tarantino P, Curigliano G, Tolaney SM. Navigating the HER2-Low Paradigm in Breast Oncology: New Standards, Future Horizons. Cancer Discovery. 2022 Sept 2;12(9):2026–30.

Bardia A, Hu X, Dent R, Yonemori K, Barrios CH, O’Shaughnessy JA, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan after endocrine therapy in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(22):2110–22.

Funding

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award number T35EB006732-17, which funded Sarah Henretta; an ASCO 2023 Conquer Cancer – Breast Cancer Research Foundation Young Investigator Award (YIA) for Diversity and Inclusion in Breast Cancer Research to Laura S. Munoz-Arcos; and a Mayer Cancer Center Clinical Trials Innovation Fund award granted to Massimo Cristofanilli.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, L.S.M.A, C.R., N.B, S.H.; methodology, N.B., S.H., E.M., L.S.M.A, M.S.S.; patient selection and enrollment, M.C., E.A.; blood sample collection, C.G., L.P.,B.P, J.M., M.K.A., O.E.; data analysis, N.B., S.H. and E.M.; data interpretation, N.B., S.H., L.S.M.A, C.R., E.M., L.P., M.S.S., E.N., C.G.; supervision, C.R., M.C. and L.S.M.A; writing-original draft preparation, N.B. and S.H; writing-review and editing, C.R., E.N., L.S.M.A, M.S.S, H.A.D, M.M. and M.K.A.; funding acquisition, L.S.M.A, M.C. and S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Weill Cornell Medicine (IRB# 1603017108), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The research adhered to the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committees, as well as the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Competing interests

M.C. and C.R. received research support from Menarini Silicon Biosystems, ANGLE, Tethis spa, Qiagen and Biorad which is not related to the work included in this manuscript. Menarini Silicon Biosystems ANGLE, Tethis spa, Qiagen and Biorad did not take part in the conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.M.C. reports grants and personal fees from Menarini.M.C., E.N. and C.R. report affiliation with Precision Medicine Action for Cancer (PMAC) (board of director), and with the International Society of Liquid Biopsy (ISLB).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bayou, N., Henretta, S., Munoz-Arcos, L. et al. Quantitative HER2 profiling on circulating tumor cells using an EpCAM-independent platform in metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Cell Int 25, 439 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-025-04036-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-025-04036-x