Abstract

Background

Despite the ongoing control and elimination efforts, malaria continues to impose a substantial burden on healthcare systems and communities in Ethiopia. Understanding its epidemiology and identifying associated factors are essential for targeted interventions. The present study thus aimed to assess malaria prevalence and associated factors among febrile patients in selected healthcare facilities of Jawi District, northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted from April to November 2023 in Jawi District, northwest Ethiopia. The study involved 420 participants who visited government-owned healthcare facilities seeking treatment for febrile illnesses. Socio-demographic information and malaria-related data were collected using a structured questionnaire. Additionally, blood samples were obtained from study participants and examined for malaria parasites using microscopy. Multivariable logistic regression was employed to identify the major explanatory factors associated with malaria.

Results

The study revealed a malaria prevalence of 41.2% (95% CI: 0.365–0.459), and Plasmodium falciparum was the predominant species (64.8%) detected. Socio-demographic factors such as lack of formal education (AOR = 2.452; 95% CI: 2.427–11.345, p = 0.047), and proximity of residence to mosquito breeding sites (AOR = 43.224; 95% CI: 3.215–25.381, p = 0.015) appeared as significant factors for malaria. Furthermore, awareness gaps regarding malaria transmission in the community (AOR = 1.384; 95% CI: 1.117–2.009, p = 0.044) were found to influence malaria vulnerability. Housing characteristics and inconsistent utilization of preventive measures were also identified as contributors to malaria prevalence among study participants.

Conclusion

The findings of the present study revealed that the rate of malaria infection in the study area was high. The transmission has a multifactorial nature, including socio-demographic, environmental, and behavioral factors. Strengthening education and awareness programs, improving housing conditions, and ensuring sustainable access to malaria diagnosis, treatment, and preventive services are essential components of effective malaria control in the study area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ethiopia stands as one of the countries deeply affected by malaria. Plasmodium falciparum is the dominant malaria parasite, causing approximately 60% of all malaria cases [1, 2]. Nearly 68% of the landmass and 60% of the population are at risk of infection, with an estimated 1.2 million outpatient visits being reported annually [3, 4]. Despite notable progress in malaria control efforts, the disease continues to present challenges, particularly in areas with favorable environmental conditions for mosquito breeding [2, 5]. The country’s diverse geography and climatic variability create heterogeneous transmission patterns. Some areas experience perennial transmission, while others face seasonal outbreaks [2, 6, 7]. In addition, population movement, drug and insecticide resistance, and political instability pose ongoing challenges to malaria control and elimination efforts in Ethiopia [8, 9].

Northwest Ethiopia, encompassing the Amhara Regional State, is characterized by a mix of highland and lowland areas, each presenting unique challenges in malaria prevention and control [10,11,12]. Jawi District, which is located in the western part of the Amhara Regional State, exemplifies the complex interplay of environmental, socio-economic, and healthcare factors influencing malaria transmission dynamics. The district's geographical features, such as large-scale agricultural practices and conducive temperature, create favourable breeding habitats for the malaria vector [13,14,15]. Moreover, seasonal variations in rainfall shape the epidemiology of malaria. Peak transmission typically coincides with the rainy seasons (April to November), though year-round transmission is also reported [14]. Socio-economic factors such as poverty, limited access to healthcare services, and substandard housing further increase the community’s vulnerability to Plasmodium infection (Jawi District Health Office, unpublished data). Despite the implementation of malaria control strategies including the distribution of insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs), indoor residual spraying (IRS), and prompt diagnosis and treatment with artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT), challenges persist in reaching all populations in need [2, 16].

Several studies in Ethiopia have examined factors associated with malaria infection, offering important epidemiological insights. For instance, Alemu et al. explored malaria prevalence in rural highland districts of south-west Ethiopia, identifying factors such as proximity to stagnant water and inconsistent use of bed nets as significant drivers [17]. Taffese et al. highlighted seasonal fluctuations, substandard housing, and travel to endemic areas as significant determinants of malaria infection in lowland areas [5]. Abate et al. assessed ITN and IRS coverage in northeastern Ethiopia, revealing implementation gaps [18], while Sena et al. emphasized that the role of occupational exposure and land-use changes were important factors in southwest Ethiopia [19]. More recently, Tesfaye and Teshome (2022) discussed the impact of socio-economic inequality and healthcare access on malaria risk in north-central Ethiopia [20].

Building on these findings, the present study focuses specifically on Jawi District, a relatively understudied yet malaria-endemic area. In doing so, it enhances our understanding of malaria epidemiology across the various contexts within Ethiopia. Understanding the prevalence of malaria and identifying associated factors is paramount for the effective prevention and control of malaria. Healthcare facilities serve as crucial entry points for diagnosing and treating malaria cases, making them important sources of data for assessing disease burden and determinant factors [21]. Accordingly, this study seeks to generate information on malaria prevalence and associated factors among fibril patients attending healthcare facilities in Jawi District, northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design, period, and settings

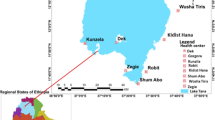

A healthcare facility-based cross-sectional study was carried out from April to November 2023 among febrile patients who attended the government-owned healthcare facilities in Jawi District, northwest Ethiopia. Jawi is one of the districts in the Amhara Regional State, and part of the Agew Awi Administrative Zone. It is bordered on the west by the Metekel Zone, on the north by the North Gonder Zone, on the east by the West Gojam Zone, and the southeast by the Dangila District (Fig. 1). The capital town of the district is Jawi, which is located 593 km northwest of Addis Ababa. According to the 2013 population projection data, the district's total population is estimated to be 104,340 (49,885 females and 54,455 males) [22]. The district is characterized by a hot “Kola” climatic condition, with a mean temperature range from 18.2 to 34.4 °C, receives an annual mean rainfall of 1569.4 mm, and has an altitude range from 648 to 1300 m above sea level. Jawi is one of the malaria-endemic districts in the Amhara Regional State, where perennial transmission occurs [14, 23]. According to the district’s Health Office report, in 2022/23, approximately 18.5% of the outpatient visits were malaria cases. Malaria diagnosis and treatment are provided free of charge in all public health facilities, as part of Ethiopia's national malaria control strategy. Additionally, individuals can access services through private clinics and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). This multi-sectoral approach ensures broader access to diagnosis and treatment in the district (Jawi District Health Office, unpublished data).

Source and target population

All outpatient visitors of the selected healthcare facilities for healthcare services during the study period were the source population of the study. Whereas individuals who experienced febrile patients (body temperature above 37.5 °C) and attended the selected healthcare facilities for treatment were our target population.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All febrile patients who visited the selected healthcare facilities for treatment during the study period and were willing to participate in the study were included. However, individuals who were severely ill, those who took antimalarial drugs before three weeks of the study, and unwilling to participate in the study were excluded.

Sample size determination

The single population proportion formula was employed to determine the sample size. By considering 16.4% as a prevalence of dry season malaria among the general population in Jawi District [14], the sample size was calculated using the formula, \(n=\frac{{\left({z}_{\alpha /2}\right)}^{2}\times p(1-p)}{{d}^{2}}\), where n = minimum sample size, P = estimation prevalence rate of malaria in the district (16.4%), (Zα/2)2 = the standard normal variable, and at 95% Confidence Interval (CI) (1.96), d = margin of error (5%) [24]. The estimated sample size was 210 study participants. Five percent of the total estimated sample size for withdrawal or missed data was added, and the sample size increased to 220. Then, the absolute sample size was multiplied by a factor of 2 for a design effect, and the final sample size became 440. The sample size was then allocated equally to the three selected health facilities. In this study, all 420 study participants were included in the analysis because of the absence of missing data and withdrawal from the original sample size.

Sampling procedures

Three government-owned healthcare facilities, namely Workmeda Health Center, Bambluk Health Center, and Jawi Primary Hospital, were selected among healthcare facilities in the Jawi District. They were selected purposively based on the accessibility and proximity of the facilities to the local community, the history of malaria transmission in the nearby community, as well as the availability of diverse settings (urban, semi-urban, and rural), and the mixed livelihood strategies of the nearby inhabitants. A systematic sampling technique was employed to select febrile patients attending the selected healthcare facilities during the study period. Based on the average number of febrile cases presenting daily, every 10th eligible individual was recruited after randomly selecting the first participant. The sample was collected for a period of six months in two seasons (minor malaria season: April to June, and major malaria season: September to November 2023). Patients who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled until the predetermined sample size was achieved.

Methods of data collection and quality assurance

Socio-demographic data collection

A structured questionnaire was employed to collect socio-demographic information from study participants (sex, age, residence, family size, marital status, occupation, income, sleeping space type, educational level), as well as Plasmodium infection-related factors (history of infection, availability, and use of ITNs, application of IRS, proximity to mosquito breeding site, and characteristics of the walls and roofs of the houses). Additionally, participants’ awareness and practice behavior were assessed using structured questions adopted from previous reports. Scores equal to or above the mean were classified as having “good” knowledge or practice, while scores below the mean were categorized as “poor”. The questionnaire was developed based on relevant literature and expert input. It was pretested on a separate 5% subsample of the target population (excluded from the main study) to assess content validity and internal consistency. The internal consistency of the questionnaire was measured using Cronbach’s alpha, which yielded a value of 0.81, indicating acceptable reliability. The questionnaire was translated using a back-translation method, and participants took an average of 20 min to complete.

Blood sample collection and processing

Blood samples were collected using a finger-prick from each selected study participant by puncturing the center of the ball of the finger with a disposable sterile lancet. The duplicate thick and thin smears were prepared within 15–30 min of sample collection, following the WHO (1991) protocol [25]. The thin smear was fixed with 100% methanol, and both smears were stained with a 3% Giemsa solution for 30 min. The stained smears were rinsed with tap water. Then, they were placed in an upright position to air dry. A thick smear was examined under 100 × oil immersion light microscopy to detect the presence of malaria parasites. If it was positive for Plasmodium, the thin smears were undergoing species identification. The blood films were examined by two independent senior medical laboratory technologists. The third senior lab personnel has settled disagreements on the results of the two laboratory technologists.

Data quality assurance

The standard operating procedures (SOP) manual was followed during blood collection, smear preparation, staining, and examination to ensure data quality. An experienced laboratory technologist has evaluated the quality of the laboratory reagents and instruments. The collection method and serial numbers were also verified. In addition, the questionnaire was made up of items written in English. It was translated into the local language, "Amharic," to ensure the data's quality and consistency. Well-trained laboratory technologists have conducted a face-to-face interview among study participants and/or guardians of children under 18 following the collection of blood samples.

Statistical analysis

The data was checked for accuracy and consistency. It was then entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and exported to SPSS version 21 software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Both descriptive statistics and logistic regression were used. The strength of association, in terms of odds ratio, between independent variables (possible associated factors) and the dependent variable (malaria prevalence) was assessed using bivariable analysis. Variables with p < 0.25 from the bivariable analysis were selected for multivariable logistic regression to identify which of the factors considered for the study were significant independent explanatory factors for malaria [26]. Finally, at a 95% CI, p < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant associated factor for malaria.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

A total of 420 individuals with fever who visited selected healthcare facilities in Jawi District participated in the study, with a response rate of 100%. Among these participants, the majority (54.1%, n = 227) were males. In terms of age distribution, (42.4%, n = 178) fell between 5 and 19 years old, while (38.1%, n = 160) were aged between 20 and 44 years. Furthermore, significant portions of the participants were self-employed (33.1%, n = 139), lacked formal education (43.8%, n = 184), and came from rural areas (71.2%, n = 299). Similarly, most individuals had thatched roofs (72.4%, n = 304) and earned less than 6000 ETB per month (71.2%, n = 299) (Table 1).

Awareness and practice behavior of study participants about malaria

Among the total study participants (50%, n = 210), exhibited awareness about malaria, including its causes and methods of transmission. Additionally, (53.3%, n = 224) of those involved in the study recognized the transmission of malaria within their community. In terms of knowledge about malaria control and prevention, (58.8%, n = 247) and (88.1%, n = 370) of participants were informed, respectively. Regarding the implementation of malaria prevention and control strategies, (63.3%, n = 266) of individuals possessed ITNs, with (52.4%, n = 220) utilized for mosquito bite prevention. Similarly, (54.3%, n = 228) of participants reported spraying their houses with IRS within the six months preceding the study (Table 2).

Malaria prevalence among study participants

The overall malaria prevalence among febrile patients in the selected healthcare facilities of Jawi District was 41.2% (95% CI: 0.365–0.459). Among these, (64.7%, n = 112) of individuals who were positive for malaria were infected with P. falciparum, and (23.1%, n = 40) with Plasmodium vivax. Whereas, P. falciparum and P. vivax mixed infections accounted for (12.1%, n = 21) (Fig. 2).

Potential explanatory associated factors for malaria in the study area

Nine factors appeared in the final regression with p < 0.05 and were found to be significant explanatory associated factors for malaria among the target population in the study area. Individuals who did not have formal education (AOR = 2.452; 95% CI: 2.427–11.345, p = 0.041) were two times more likely to be infected with malaria than individuals who completed higher education. The possibility of malaria infection was 43 times higher among individuals who lived within less than 1 km distance from mosquito breeding sites (AOR = 43.224; 95% CI: 3.215–25.381, p = 0.047) than those who lived more than 2 km away. Similarly, study participants whose houses were made from stonewall (AOR = 4.333; 95% CI: 2.725–9.411, p = 0.006) were found to have a higher risk of Plasmodium infection. In addition, study participants who were unaware of the mode of malaria transmission were 37 times more likely (AOR = 37.348; 95% CI: 4.464–29.139, p = 0.033) to be infected with Plasmodium than informed individuals. Individuals who were unaware of the transmission of malaria in the community (AOR = 1.384; 95% CI: 1.117–2.009, p = 0.015) were also identified as possible associated factors for malaria. Likewise, study participants who did not utilize bed nets were found 2-times higher risk of Plasmodium infection (Table 3).

Malaria cases across the study sites and period

The Bambluk Health Center recorded the highest prevalence, accounting for (38.2%, n = 66) of all malaria cases in the study area. P. falciparum, P. vivax, and mixed infections were recorded in all three healthcare facilities. The majority of P. falciparum infections were reported from Jawi Primary Hospital, with (39.1%, n = 52) of the total (n = 133) P. falciparum infections recorded. Furthermore, nearly half of the P. vivax infection was reported from the Bambluk Health Center (Fig. 3). In addition, approximately equal proportions of Plasmodium infection were reported from the two malaria seasons: the minor malaria season (April-June) and the major malaria season (September–November) (Fig. 4). Yet, slight prevalence decrements were recorded among the P. falciparum infection in October, and mixed infection in April and May (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Malaria remains a significant public health concern, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where its impact is most noticeable [3]. Ethiopia, located within this malaria-endemic belt, faces substantial challenges with high malaria prevalence, especially in areas like Jawi District, where transmission persists year-round [2, 14]. This study contributes to a deeper understanding of malaria prevalence and associated factors among febrile patients who attended healthcare facilities in Jawi District, northwest Ethiopia.

The current investigation revealed a malaria prevalence of 41.2% among febrile patients attended in selected healthcare facilities of Jawi District, underscoring the persistent burden of the disease in the area. This prevalence exceeds recent reports from other malaria-endemic areas in Ethiopia. For instance, studies conducted at Shewa Robit Health Centre (19.0%) [20], Mizan Tepi University Teaching Hospital (20.7%) [27], Lake Tana and surrounding areas (24.7%) [28], East Shewa of Oromia Regional State (25%) [29], and Hamusit Health Centre (29.0%) [30], reported lower malaria prevalence compared to the present study. Additionally, the prevalence of malaria in this study surpasses the national pooled prevalence of malaria (25.8%) [1]. A systematic review by Kendie et al. also indicated a lower pooled prevalence of malaria among adults in Ethiopia (13.6%) [31], which is approximately one-third of the prevalence recorded in this study. On the other hand, the prevalence reported in this study is lower than a study from the Haro Limmu district of Western Ethiopia (49.4%) [32], but comparable to a report among febrile children in the same district as our study (43.8%) [33].

The variability in malaria prevalence can be attributed to multiple factors. Differences in Anopheles mosquito breeding sites, altitudinal disparities, and microclimate variations play significant roles. Additionally, lifestyle shifts, geographic location, community awareness levels, the establishment of dams or irrigation networks, economic status, and variations in malaria diagnostic methods could also contribute to the differences in prevalence rates. In our study area, lower community awareness, where approximately half of the participants had no good knowledge about malaria. Similarly, inadequate use of ITNs (47.6%) by respondents may also contribute to higher local transmission. Environmental and geographical factors specific to the Jawi District, such as its lowland climate and presence of water bodies, may further promote the breeding of vectors. In contrast, studies reporting lower prevalence rates [20, 27,28,29,30] were often conducted in areas with differing ecological conditions. Likewise, other factors may underpin the higher prevalence of malaria infection observed in this particular study. Firstly, the data collection period coincided with a national malaria outbreak in 2023, where reported cases of the national malaria prevalence increased by 150% and 120% compared to the same periods in 2021 and 2022, respectively [34]. Furthermore, ongoing armed conflicts and mass displacements of populations between neighboring regions and districts could have disrupted malaria prevention and control endeavors, potentially amplifying prevalence rates [34, 35].

In the present study, P. falciparum and P. vivax were identified as the two Plasmodium species detected, comprising 64.7% and 23.1% of cases, respectively. This finding aligns with national trends in Plasmodium species distribution [1]. However, a notable 12.1% of individuals diagnosed with malaria were found to be co-infected with P. falciparum and P. vivax. The prevalence of P. falciparum infection in this study is in line with recent reports from different parts of Ethiopia, such as Hamusit (67.2%) [30] and Wogera (65%) [36], although it diverges from rates reported in other areas such as Mizan Tepi University Teaching Hospital (58.3%) [27], and Ziquala district (57.1%) [37]. Likewise, the prevalence of P. vivax infection is consistent with findings from Lake Tana and its surroundings (23.7%) [28], but differs from rates reported in other regions [36,37,38].

This inconsistency may be attributed to differences in study settings, including climate, study period, and malaria prevention and control approaches. In addition, factors such as the ability of P. falciparum to infect all stages of red blood cells, resistance patterns to first-line treatments, and the lowland climates of the study area, which are conducive to P. falciparum proliferation, may contribute to the higher proportion of P. falciparum over P. vivax. Furthermore, the coexistence of P. vivax and mixed infections highlights the complex dynamics of malaria transmission in the district, emphasizing the need for multifaceted control strategies tailored to the diverse malaria parasite species taken into account.

Several socio-demographic and environmental factors emerged as significant determinants of Plasmodium infection in the present study. Individuals lacking formal education (AOR = 2.452; 95% CI: 2.427–11.345, p = 0.041) were notably more vulnerable to malaria, emphasizing the importance of health education in raising awareness and promoting preventive practices. Proximity to mosquito breeding sites, as indicated by living within a kilometre distance from such sites (AOR = 43.224; 95% CI: 3.215–25.381, p = 0.047), emerged as a critical factor, indicating the influence of environmental factors on malaria transmission. Moreover, housing characteristics, such as the material used for walls, significantly impacted malaria, suggesting the importance of housing improvements as one of the malaria control strategies. On the other hand, despite age not emerging as a statistically significant associated factor in the multivariable analysis, a higher prevalence of malaria was observed among individuals under 20. This may be due to underdeveloped immunity, higher exposure risk, and limited use of preventive measures. Thus, the findings of the present study underscore the need for integrated approaches that address both socio-demographic vulnerabilities and environmental determinants of malaria transmission in the study area.

The study revealed gaps in malaria-related knowledge and practices among participants. While a substantial proportion demonstrated awareness of malaria and its transmission, deficiencies in understanding key preventive measures were evident. Inconsistent utilization of ITNs and IRS underscores the need for sustained behavioral interventions and community engagement to enhance malaria control efforts. Comprehensive educational campaigns targeting vulnerable populations and promoting consistent adherence to preventive measures are essential to address these gaps and improve community resilience against malaria transmission.

The findings underscore the multifactorial nature of malaria transmission in Jawi District, necessitating integrated control approaches that address the complex interplay of socio-demographic, environmental, and behavioral factors. Strengthening health education and awareness programs, particularly targeting vulnerable populations, can empower communities to adopt preventive measures effectively. Additionally, environmental management strategies aimed at reducing mosquito breeding sites and improving housing conditions are paramount. Sustainable access to malaria diagnosis, treatment, and preventive services must be ensured to promptly identify and manage cases, mitigating disease transmission. By adopting a holistic approach that combines vector control, community engagement, and healthcare system strengthening, stakeholders can effectively mitigate the burden of malaria and improve health outcomes in the district.

Limitations of the study

The study's cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw causal conclusions and explore temporal trends. The other limitation is its reliance solely on healthcare facility attendees, which could introduce bias; individuals who do not seek healthcare due to mild symptoms, limited access, or other barriers were not represented. As a result, the finding may not capture a more accurate picture of malaria epidemiology in the study area. Furthermore, the study was conducted from April to November, covering the peak malaria transmission season, which may not fully capture year-round transmission dynamics. The other notable limitation of the study is the exclusion of several important variables, such as enrollment months, occupation, etc., from the multivariable regression analysis. Relying on a p-value cutoff of p < 0.25 for including variables may have overlooked potentially significant factors that could influence malaria prevalence.

Conclusion

The present study revealed a persistently high prevalence (41.2%) of malaria among febrile patients visiting healthcare facilities in Jawi District. P. falciparum is the dominant parasite detected. Lack of formal education, proximity to mosquito breeding sites, limited knowledge of malaria transmission, and inconsistent preventive practices of mosquito bites were identified as the potential explanatory factors associated with malaria in the study area. This underscores the need for a comprehensive approach addressing sociodemographic, environmental, and behavioral factors to effectively tackle malaria transmission in the district.

Data availability

The data used and analysed in this study are available within the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ACT:

-

Artemisinin-based combination therapy

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odd ratio

- APHI:

-

Amhara Public Health Institute

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COR:

-

Crude odd ratio

- IRS:

-

Indoor residual spray

- ITNs:

-

Insecticide treated nets

- LLINs:

-

Long-lasting insecticidal nets

- NGOs:

-

Non-governmental Organization

- SOP:

-

Standard operating manual

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Deress T, Girma M. Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax prevalence in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Malar Res Treat. 2019;2019:7065064.

FMOH. National Malaria Elimination Strategic Plan: 2021–2025. Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, 2020. http://repository.iifphc.org/handle/123456789/1526. Accessed 21 Mar 2023.

FMOH. National Malaria Elimination Roadmap. Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, 2017. Available from: http://repository.iifphc.org/bitstream/handle/123456789/1438/Malaria-Elimination-Roadmap-Ethiopia%202017.pdf. Accessed 21 Mar 2023.

PMI. Ethiopia Malaria Operational Plan FY 2022. Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, 2022. Available from: https://d1u4sg1s9ptc4z.cloudfront.net/uploads/2023/01/FY-2023-Ethiopia-MOP.pdf. Accessed 21 Mar 2023.

Taffese HS, Hemming-Schroeder E, Koepfli C, Tesfaye G, Lee MC, Kazura J, et al. Malaria epidemiology and interventions in Ethiopia from 2001 to 2016. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7:103.

Kibret S, Lautze J, Boelee E, McCartney M. How does Ethiopian dam increase malaria? Entomological determinants around the Koka reservoir. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:1320.

Warkaw YM, Mitku AA, Zeru MA, Ayele M. Spatial pattern and predictors of malaria in Ethiopia: application of auto logistics regression. PLoS ONE. 2022;17: e0268186.

Messenger LA, Shililu J, Irish SR, Anshebo GY, Tesfaye AG, Ye-Ebiyo Y, et al. Insecticide resistance in Anopheles arabiensis from Ethiopia (2012–2016): a nationwide study for insecticide resistance monitoring. Malar J. 2017;16:469.

Yalew AW. Achievements, gaps, and emerging challenges in controlling malaria in Ethiopia. Front Trop Dis. 2022;2: 771030.

Vajda ÉA, Webb CE. Assessing the risk factors associated with malaria in the highlands of Ethiopia: what do we need to know? Trop Med Infect Dis. 2017;2:4.

Yalew WG, Pal S, Bansil P, Dabbs R, Tetteh K, Guinovart C, et al. Current and cumulative malaria infections in a setting embarking on elimination: Amhara, Ethiopia. Malar J. 2017;16: 242.

Nigussie TZ, Zewotir TT, Muluneh EK. Seasonal and spatial variations of malaria transmissions in northwest Ethiopia: evaluating climate and environmental effects using a generalized additive model. Heliyon. 2023;9: e15252.

Tilahun A, Yimer M, Gelaye W, Tegegne B. Prevalence of asymptomatic Plasmodium species infection and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care at Fendeka town health facilities, Jawi District, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15: e0231477.

Amare A, Eshetu T, Lemma W. Dry-season transmission and determinants of Plasmodium infections in Jawi district, northwest Ethiopia. Malar J. 2022;21:45.

Tamir Z, Animut A, Dugassa S, Belachew M, Abera A, Tsegaye A, et al. Plasmodium infections and associated risk factors among parturients in Jawi district, northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Malar J. 2023;22:367.

Genet T, Alemu K, Nigusie A. Insecticide treated net, possession, spatial distribution, utilization and associated factors among households of Jawi District, Northwest Ethiopia. J Community Med Health Educ. 2018;8: 635.

Alemu A, Tsegaye W, Golassa L, Abebe G. Urban malaria and associated risk factors in Jimma town, south-west Ethiopia. Malar J. 2011;10:173.

Abate A, Degarege A, Erko B. Community knowledge, attitude and practice about malaria in a low endemic setting of Shewa Robit Town, northeastern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:312.

Sena LD, Deressa WA, Ali AA. Predictors of long-lasting insecticide-treated bed net ownership and utilization: evidence from community-based cross-sectional comparative study, Southwest Ethiopia. Malar J. 2013;12: 406.

Tesfaye A, Teshome T. Prevalence and associated factors of malaria infection among outpatients visiting Shewa Robit Health Center. Northcentral Ethiopia J Trop Med. 2022;2022:1784012.

WHO. Global Technical Strategy for Malaria 2016–2030. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data; Geneva, World Health Organization, 2015. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/global-technical-strategy-for-malaria-2016-2030.pdf.

CSA. Population Projection of Ethiopia for All Regions at the Wereda Level from 2014–2017. 2013. Available from: http://www.statsethiopia.gov.et/population-projection/. Accessed 30 Mar 2023.

PMI. Malaria Operational Plan FY 2023. Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, 2023. Available from: https://d1u4sg1s9ptc4z.cloudfront.net/uploads/2023/01/FY-2023-Ethiopia-MOP.pdf. Accessed 26 Mar 2023.

Daniel WW. Biostatistics: a foundation for analysis in the health sciences, 7th Edn. John Wiley & Sons, New York, USA. 1999.

WHO. Basic Laboratory Methods in Medical Parasitology. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1991. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/40793. Accessed 22 Mar 2023.

Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med. 2008;3:17.

Duguma T, Tekalign E, Muleta D, Simieneh A. Malaria prevalence and risk factors among patients visiting Mizan Tepi University Teaching Hospital, southwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2022;17: e0271771.

Adugna F, Wale M, Nibret E. Prevalence of malaria and its risk factors in Lake Tana and surrounding areas, northwest Ethiopia. Malar J. 2022;21:313.

Tadesse F, Fogarty AW, Deressa W. Prevalence and associated risk factors of malaria among adults in East Shewa Zone of Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18: 25.

Negatu GA, Abebe GA, Yalew WG. Prevalence of malaria and associated factors among malaria-suspected patients attending Hamusit Health Center, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. J Parasitol Res. 2022;2022:1306049.

Kendie FA, Hailegebriel W, Kiros T, NibretSemegn E, Ferede MW. Prevalence of malaria among adults in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trop Med. 2021;2021:8863002.

Bidu KT, Babure ZK. Prevalence of malaria and associated factors among febrile patients visiting Kalala Health Center in Haro Limmu Woreda, East Wollega Zone, Western Ethiopia, 2016. Epidemiology. 2019;9:365.

Hailu T, Alemu M, Mulu W, Abera B. Incidence of Plasmodium infections and determinant factors among febrile children in a district of Northwest Ethiopia; a cross-sectional study. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines. 2018;4:8.

WHO. Malaria deaths fall, but vector resistance to insecticides a worrying trend. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2023. https://www.afro.who.int/countries/ethiopia/news/malaria-deaths-fall-vector-resistance-insecticides-worrying-trend. Accessed 21 Feb 2023.

MPI. Ethiopia’s Growing Malaria Burden. Blog on 25 Oct, 2023. Available from: https://www.malariapartnersinternational.org/ethiopias-growing-malaria-burden/. Accessed 21 Feb 2023.

Tsegaye AT, Ayele A, Birhanu S. Prevalence and associated factors of malaria in children under the age of five years in Wogera district, northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16: e0257944.

Debash H, Bisetegn H, Ebrahim H, Feleke DG, Gedefie A, Tilahun M, et al. Prevalence and associated risk factors of malaria among febrile under-five children visiting health facilities in Ziquala district, Northeast Ethiopia: a multicenter cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17: e0276899.

Duguma T, Nuri A, Melaku Y. Prevalence of malaria and associated risk factors among the community of Mizan-Aman town and its catchment area in Southwest Ethiopia. J Parasitol Res. 2022;2022:3503317.

WMA. World medical association declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:373–4.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the study participants for their voluntary involvement and cooperation during the data collection process. We also extend our appreciation to the healthcare staff and data collectors for their valuable support and dedication. Special thanks go to Mengie Belayneh (PhD) of Mattu University, Ethiopia, for preparing the map illustrating the study sites.

Funding

No funding is received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AD, SY, and AH conceived the study. SY, FA, EN, and MA carried out the statistical analysis. All authors have contributed to the results interpretation and manuscript drafting.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Before data collection was initiated, ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of the College of Natural and Computational Sciences, Debre Markos University (Ref: BIO,425/17/201). A letter of permission was also sought from the Amhara Public Health Institute (APHI) to obtain support from the relevant governmental and public institutions.

The study's objective, potential risks, and benefits were thoroughly explained to health experts, heads of health facilities, and study participants or parents/guardians. All study participants and guardians of children under 18 years of age were informed about the study and gave their consent. Every response was handled confidentially and anonymously. All methods were carried out following the Helsinki Declaration [39].

Consent to publication

All authors have approved the submission of the final copy for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dagnew, A., Yeshanew, S., Nibret, E. et al. Prevalence of malaria and associated factors among febrile patients in selected healthcare facilities of Jawi District, northwest Ethiopia. Malar J 24, 327 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-025-05509-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-025-05509-0