Abstract

Background

Despite significant progress in cardiovascular disease (CVD) management, it remains a public health priority and a global challenge. Within the disease process, health care after a cardiovascular event (secondary prevention) is essential to prevent recurrences. Nonetheless, evidence has suggested the existence of gender disparities in CVD management, leaving women in a vulnerable situation. The objective of this study is to identify all available evidence on the existence of gender differences in health care attention after a major adverse cardiovascular event.

Methods

A scoping review following the structure of PRISMA-ScR was conducted. To define the inclusion criteria, we used Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) population, concept, context framework for scoping reviews. A systematic search was performed in MEDLINE (PubMed), EMBASE and Cochrane. The methods of this review are registered in the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (INPLASY) (INPLASY202350084).

Results

The initial search retrieved 3,322 studies. 26 articles were identified manually. After the reviewing process, 93 articles were finally included. The main intervention studied was the pharmacological treatment received (n = 61, 66%), distantly followed by guideline-recommended care (n = 26, 28%) and cardiac rehabilitation (CR) referral (n = 16)”. Literature described gender differences in care and management of secondary prevention of CVD. Women were less frequently treated with guideline-recommended medications and seem more likely to be non-adherent. When analysing guideline recommendations, women were more likely to make dietary changes, however, men were more likely to increase physical activity. Studies also showed that women had lower rates of risk factor testing and cholesterol goals attainment. Female sex was associated with lower rates of cardiac rehabilitation referral and participation.

Conclusions

This review allowed us to compile knowledge on the existence of gender inequalities on the secondary prevention of CVD. Additional research is required to delve into various factors influencing therapeutic disparities, referral and non-participation in CR programs, among other aspects, in order to improve existing knowledge about the management and treatment of CVD in men and women. This approach is crucial to ensure the most equitable and effective attention to this issue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), refers to a group of medical disorders that affect the heart and blood vessels and cause a variety of health problems, such as coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, or peripheral arterial disease [1]. The etiology of CVD may be due to multiple factors and its increasing incidence is associated with a high frequency of individual risk factors, such as high blood pressure (BP), smoking, and obesity. Environmental determinants, demographic changes towards an aging population, the appearance of risk factors in developing countries and socioeconomic variables, among others, also play and important role in the incidence of CVD [2].

Despite significant progress in the prevention and treatment of CVD, it remains a public health priority and a global health challenge. It is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in Europe and worldwide. In 2020, CVD accounted 1.70 million deaths in the European Union, 36% of all deaths and about 20% of all premature deaths (before the age of 65) [3, 4].

Within the disease process, health care after a cardiovascular event (so-called secondary prevention) is essential to reduce mortality and prevent recurrences [5]. This secondary CVD prevention involves a combination of elements such as lifestyle changes to minimize risk factors (e.g. increased daily activity and smoking cessation), adherence to cardioprotective medication, participation in cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programs and follow-up visits to monitor and control certain parameters (cholesterol, BP, body mass index or BMI) by healthcare professionals [6, 7].

The World Health Organization uses the term “gender medicine” to refer to the study of how biological (sex-based) and socio-economic and cultural (gender-based) differences influence people's health. [8, 9]. “Gender medicine” is the study of how diseases differ between men and women in terms of prevention, clinical manifestation, diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, prognosis, psychosocial effects and interactions with the health care system [10]. Regarding CVD management, evidence has suggested the existence of gender disparities, leaving women in a vulnerable situation [5, 11]. However, while this has been widely described for primary prevention and hospital care during the cardiac event [12, 13], gender inequalities in secondary prevention are much less well known.

Therefore, the objective of this study is to identify and understand the best evidence on the existence of gender differences in health care attention after a major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE). The results of this comprehensive review hold the potential to fill knowledge gaps and provide valuable information to address gender inequalities in the field of secondary CVD prevention.

Methods

Review of the literature

This scoping review was developed following the guideline structure of preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews statement (PRISMA- ScR’s) [14]. The methods were specified and registered in the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (INPLASY) on 23 May 2023 (registration number INPLASY202350084) [15].

Eligibility criteria

To define the inclusion criteria, we used Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) population, concept, context framework for scoping reviews [16]. So, our population was the published literature related to secondary prevention in patients who have suffered a MACE. We defined MACE as those people with myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, or stroke. These diagnoses correspond to codes I21 and I60-I63 of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10). Secondary CVD prevention can be understood as any strategy aimed to prevent a recurrent MACE and reduce the likelihood of a first MACE in patients with known CVD, including coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular arterial disease, peripheral arterial disease, and atherosclerotic aortic disease. The main secondary prevention strategies studied were: pharmacological treatment; cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programs, defined as a medically supervised program designed to improve cardiovascular health after CVD, including exercise counselling and training, education on heart-healthy lifestyle and risk factor control; health system follow-ups; and guideline-recommended lifestyle counselling. The concept of this scoping review are studies about gender inequalities, as the unfair and preventable differences that exist between women and men in the state of health care. Finally, the context is focused on the health services setting and, in particular, on the secondary CVD prevention measures, such as disease management, pharmacological treatment regimen, adherence, rehabilitation, access to services, visits to general practitioner and nurse and referral to specialists.

We included studies of any design, setting or duration if they reported gender inequalities in secondary prevention on patients with MACE. Articles in English were selected because it is the language in which most of the publications are written, in addition to Spanish, which is the native language of the authors. We restricted the search to articles from the last ten years (2014 to 2023) in order to explore MACE’s secondary prevention intervention related to the latest guideline recommendations.

Studies that focused on pathologies other than MACE, addressed primary prevention, treatment of CVD risk factors or explored medical care during the event were excluded. We also excluded publications that analysed differences due to biology, e.g., different pharmacological effectiveness due to biological factors associated with sex. We excluded those publications that focused on health outcomes instead of health care, such as quality of life or functionality. Finally, short communications (conference abstracts or posters) without full text available were not included.

Search strategy and study selection

Three concepts combined were used to develop our search strategy: (1) MACE, (2) gender disparities, and (3) secondary prevention measures.

Extensive literature searches were conducted in MedLine (via Pubmed), Cochrane and Embase, from inception to 20 February 2023 with some restrictions (abstract available, last ten years, adults only and language: English and Spanish).

Searches were piloted in MedLine (Pubmed) and then adapted to run in the other databases assisted by the Polyglot Search Translator [17]. A manual or snowball search was also conducted to identify other relevant studies in additional sources.

The complete search strategy is shown in the Supplementary material Additional file 1. Search terms used are shown in Fig. 1.

Study screening and selection was carried out in different phases. First, duplicate studies were automatically deleted by the online software CONVIDENCE [18] and manually with RAYYAN [19]. Secondly, potentially relevant articles were identified by examining title and abstract of the retrieved articles. Third, a final selection was made after reading the full text of the articles. The selection process was conducted by two reviewers independently (I.L-F. and I.A-P), and a third reviewer participated if disagreement (S.M).

For excluded studies, the reason for exclusion was documented.

Data extraction and synthesis

Following the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis [16], we developed a summary sheet to extract the main characteristics and results of the included studies. Data were organised and reported in a table based on major conceptual categories such as: description of general bibliographic data (author(s), year of publication, study country), design of the study, population (sample size and type of cardiovascular event), type of secondary prevention intervention, and main findings related to gender inequalities. Type of intervention was divided into pharmacological treatment, considering both prescription and medication adherence, guideline recommended care, including achievement of the target parameters recommended (guideline goals) and healthy lifestyle recommendations, CR, and use of health services. Studies were reviewed one at a time, combining the studies referred to the same category. We performed a narrative synthesis to accompany the tabulated results and described them more precisely.

Results

As it can be observed in PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 2), the search strategy produced 3,322 potentially relevant studies. 26 articles were identified manually or by snowball search. After removing 892 duplicates of those remaining, 2,334 were excluded after reviewing the title and abstract and another 14 were not retrieved for their inadequacy according to the eligibility criteria previously defined. After reviewing the full text of the remaining articles [20], another 15 were excluded. The reasons for exclusion were due to studies exploring pathologies other than MACE (n = 1), primary prevention (n = 1), care during the event (n = 3) or differences due to biology or other (n = 10). Finally, a total of 93 articles were selected.

In Supplementary material: Additional file 2 to 5, Appendix Tables 1 to 4 present detailed information of the 93 studies included in our scoping review grouped by type of intervention [5, 12, 13, 20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109].

Among the 93 included articles, 27 studies were conducted in European countries, 25 in the USA, 8 in Canada, 7 in Australia and the rest in different world locations. The most common study design was the prospective cohort (n = 50, 54%). The pathologies analysed focused on MACE in their various forms, such as acute myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, and stroke.

The following major categories of secondary CVD prevention are described in Table 1. As it can be observed, the main intervention studied in the literature is the pharmacological treatment received after MACE (n = 61, 66%), distantly followed by guideline-recommended care (n = 26, 28%) and referral to CR (n = 16). Finally, there were only 9 publications about gender inequalities in the use of health services after a MACE.

Now we will proceed to explain the main outcomes obtained for each of the secondary prevention interventions. A resume of the main results is shown in Fig. 3.

Health service use

Understood as the process of accessing and using health services, we found nine studies about health service use. We considered various medical services, such as visits to health practitioners (general practitioners, nurses) or referrals to specialists (cardiologists), number of medical appointments, access to the emergency department, and other forms of health care intervention.

According to medical appointments, some studies showed that the average number of visits to a health practitioner was lower in men, compared to women [45, 48, 5, 100]. However, women were less likely to receive care from a primary care provider, such as, receive dietary advice or have all cardiovascular risk factors measured (low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol or LDL-C, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol or HDL-C, BP, and haemoglobin A1c or HbA1C) [5, 80, 100]. Women seemed to have worse communication with their healthcare provider and were more likely to receive home health care [80].

In terms of referral to other specialists, two studies found that a greater proportion of men than women used specialist care (79.0% vs. 70.6%, p < 0.001), being women less likely to be seen by a cardiologist (77.1% versus 85.7%; p < 0.001), and men having almost two more visits on average than women did [45, 74]. On the other hand, the study of Abrahamyan et al. observed similar referral to other specialists across genders, although it was also noted that the majority of patients seen in heart failure clinics were men [21].

Finally, one study showed that men had a greater utilisation of emergency care services (57.6% vs. 52.7%, p < 0.001), and more visits to the emergency room (1.32 vs. 1.15 visits, p < 0.001) than women [45], but some other agreed that it was women who were more likely to use emergency department services [76, 87].

Cardiac rehabilitation

CR are a comprehensive, multidisciplinary chronic disease management program that incorporates patient assessment, nutritional counselling, cardiovascular risk factor management, psychological management, exercise training, and physical activity counselling. As a result, substantial evidence indicates that CR participation is effective in improving CVD management [93].

We included sixteen studies on gender differences in referral (referral order from the health practitioner to an outpatient CR program), enrolment (initiating the program), and attendance (participation in most or all of the sessions of the program) of CR programmes, as well as literature on adherence, potential barriers, and reasons for CR dropout.

Four studies found that female sex was associated with lower rates of CR referral [34, 44, 56, 93], while two other papers found no statistically significant gender difference [58, 101]. Gravely et al. [44] studied potential effects of referral strategies on access to CR. This study showed that systematic referral alone resulted in 6.5 times more referrals than usual referral and combined with a liaison facilitated strategy resulted in a ten times greater referral rate. They found that men were significantly more likely to be referred to CR than women using a liaison-facilitated strategy (63.5% and 48.6%, p < 0.01), although there were no significant gender differences following systematic referral (70.5% and 68.6%, p = 0.70) or the combined approach (85.6% and 84.2%, p = 0.73).

Regarding enrolment and attendance, several studies showed that women were less likely to enrol in CR programs and had lower rates of attendance [34, 41, 44, 56]. The odds of women attending a CR program were lower than men being between 0.64–0.87 (95% Confidence interval (95%CI)) [5, 77]. This is similar to the study published by Resurrección et al. [84], which describes that female patients have up to four times higher odds of non-participation (Odds Ratio (OR) range 1.64–4.17).

Another study [93] summarised that even referral rates had increased from 2007, improvements in participation have not been reported, remaining female CR attendance unchanged from 1982. As seen previously [44] and according to the study by Oosenbrug et al. [77], CR enrolment favoured women in studies where patients were systematically referred.

On the other hand, only one study [52] conducted in Korea, found no differences in terms of participation between gender. In terms of adherence to CR programmes, Samayoa et al. [89] concluded that there were no significant gender differences in programs of < 12 weeks; however, in programs of ≥ 12 weeks, men were significantly more adherent than women.

Four studies explored potential barriers and reasons for non-participation and dropout from a CR program in women [56, 85, 86, 96].

The reasons were grouped into similar categories, such as, intrapersonal, interpersonal, logistical barriers, characteristics about the program or health system issues. They are described in detail in supplementary material: Additional file 3: Table 2. The most common reasons were family responsibilities, transport or distance issues, fear of exercise, uncertainty about the purpose of CR, lack of insurance, lack of endorsement and recommendation to attend to the program, and health beliefs about CVD.

Finally, the study by Angus et al. [22] highlights the complexity of adopting new health practices learned in a CR program, showing how people struggled to find a place for health practices in everyday life. So, some participants tried to conceal health-related activities at work to avoid unemployment or tried to minimise family concern by hiding their illness so that they did not seem "weak". They described the importance of the cooperation of others to support lifestyle changes. Participants tried to educate and inspire family members, but they often met with resistance, making it hard to maintain healthy habits.

Guideline recommended care: healthy lifestyle

Worldwide guidelines recommend adopting healthy lifestyles to prevent CVD. We found several studies that showed no gender differences with regard to get healthy lifestyle advice or education [37, 69, 81, 90, 91]. One study showed that despite small improvements, health behaviours (physical activity, healthy diet, or smoking) remained worse than in general population one year after the event [64].

Women were more likely to report more often dietary changes, such as reducing their dietary fat intake (p < 0.001) [37, 69, 90, 91], whereas men seemed to be more physically active [32, 69, 70, 78, 90]. Female gender was an independent predictor of physical inactivity, with women having 1.37 times the odds of being less active from before to 12-months after acute myocardial infarction (95%CI: 1.21–1.55) [70, 78]. Regarding smoking, two studies showed that the rate of persistent smoking/relapse or reduction was similar in both sexes [64, 81].

Guideline recommended care: guideline goals

Guidelines recommend certain controls and goal targets after a MACE. One study [108] showed that cardiovascular risk factor control was generally suboptimal in both men and women for all risk factors examined (total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C, BP, and glucose targets). On the other hand, several studies [62, 73, 102] agreed that risk factor testing was consistently less frequent among women (p < 0.001). Lee et al. [62] also added that those patients who had risk factors assessed more than once increased their odds of target achievement by > 5%.

Regarding gender differences in risk factors measured, less female had their weight measured [37], and significant gender differences were found in BP control and lipid profiles [37, 46]. Naicker et al. [72] showed that women were less likely to have their lipid profiles taken (OR = 1.17 [95%CI, 1.03–1.33]), but were more likely to have two BP measurements (OR = 0.83 [95%CI, 0.71–0.96]), and to be referred to a dietician or weight loss program (OR = 0.87 [95%CI, 0.76–0.98]).

Several studies examined gender differences in the achievement of recommended therapeutic goals. Two of them found no statistically significant differences when considering therapeutic goals, such as, LDL-C, non-HDL-C, BP, HbA1, BMI or physical activity [90, 98].

Regarding control of lipid targets, four studies observed no gender differences [43, 59, 78, 90], while five found that females were less likely to meet the target lipid goal recommended [49, 66, 93, 99, 108]. The number of studies showing gender differences increased when only LDL cholesterol target was considered. Only one study showed no statistically significant gender difference in the achievement of the therapeutic goal (LDL-C < 70mg/dl) [91], compared with seven studies in which women were less likely to achieve LDL-cholesterol targets [20, 27, 37, 49, 62, 102, 105].

Finally, when other therapeutic goals were considered, three studies found that women were less likely to achieve BP targets [46, 50, 59], while two others showed no difference [37, 102]. For HbA1c, one study found a higher proportion of women achieving HbA1c target [62] whereas another showed otherwise [37].

Pharmacological treatment: prescription

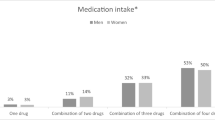

Four main drugs are recommended for secondary prevention: aspirin or other antiplatelet drugs, statins, Beta blockers (BBs), and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). We found fifty-six studies that examined gender differences in pharmacological treatment. The main results are summarised in Table 2.

As it can be observed, the majority of papers reviewed found that women were less frequently treated than men for all the drugs analysed.

These results were also observed when other comedications frequently used in secondary CVD prevention were analysed (Table 3).

Also, some studies explored gender differences in adequate statin dose. Twelve studies found that women were less likely than men to receive high-intensity statin therapy (p < 0.05) [20, 24, 38, 39, 55, 66, 74, 79, 80, 91, 99, 100].

Pharmacological treatment: adherence

Medication adherence is defined by the World Health Organization as “the degree to which the person’s behaviour corresponds to the agreed recommendations from a health care provider” [110]. Our search found eight articles that explored adherence to treatment. Four of them showed no statistically significant gender differences [67, 71, 91, 101]. In addition, Setny et al. [91] added that there was no difference in the reasons for treatment discontinuation. On the contrary, the other four found gender differences [26, 40, 61, 74]. Bhuyan et al. [26] observed that cost-related medication non-adherence behaviours were more likely (1.54 times 95%CI, 1.33–1.77) among women, such as skipping medication, taking less medication, or delaying refills.

Discussion

The most important contribution of this study is to summarize the existing literature on gender inequalities in secondary prevention of CVD. In doing so, we are able to show that gender differences still exist and to emphasise the importance of incorporating a gender perspective in secondary prevention interventions for CVD.

Overall, 93 articles reporting the four main outcomes for secondary prevention of MACE were identified in this scoping review, namely: health service use, CR, guideline recommended care and pharmacological treatment. To begin with, the literature reviewed show the existence of gender differences in terms of health care and management of secondary prevention of CVD. Thus, in relation with the use of health services, women are more likely to engage with primary healthcare [45, 48], probably due to a higher awareness of disease prevention. On the contrary, they were less likely to use specialist care, such as emergency services or to be seen by a cardiologist. The main findings for CR followed the same line; female sex was associated with lower rates of CR referral, although these rates improved when systematic referral was used. So, women are less likely to enroll, participate and adhere to the CR program. When analyzing guideline-recommended care, we found several studies that reported that women were more likely to make dietary changes, such as reducing fat intake. On the other hand, men were more likely to increase their physical activity. Women had lower rates of risk factor testing and they seem to be less likely to reach cholesterol goal targets. Regarding pharmacological treatment, studies showed that women were less frequently treated with guideline-recommended medications, including lower-intensity statins, and they seem more likely to be non-adherent.

According to the use of health services, women are subject to less therapeutic efforts, their cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs) are less frequently monitored [72, 80, 102, 108] and they are less likely to receive specialist care or to have access to specific treatments, such as CR programs. It could be explained by an androcentric bias in health care (lower number of visits to the emergency room [87], lower cardiology referrals [74]) that has not been internalized or assumed by health professionals or by the general population. The study by Venditti et al. [111] suggests that undertreatment in women might be related to lower awareness of CVD, less social support, low socioeconomic status and lack of insurance, barriers that are thought to limit women's access to care, making it difficult to monitor and control risk factors, disproportionately affecting women and widening gender inequalities. Other studies [21, 45] defend the idea that women receiving less care could be explained by men presenting more exacerbations and because of their clinical characteristics of their comorbidities (e.g. ischemic etiology, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, age…), although multimorbidity burden has shown to be similar in both sexes. Moreover, the study of Okunrintemi et al. [76], with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease patients, showed that women reported poor communication with their healthcare providers and poor satisfaction with their healthcare experience, reflecting a potential gender bias among the health providers. Of note, other studies suggest that outcomes may be better for female patients treated by female physicians [112, 113].

Regarding CR programs, women are referred less, consequently, they enroll less, and they also have lower attainment and consecution of these programs. The study by Supervia et al. [96] examined the barriers for women in this area. They identified a complex range of barriers (socioeconomic, demographic, medical and societal), some of them which can be addressed to reduce gender inequalities. Women frequently carry a burden of family responsibilities assuming the family care giver role [34, 56, 85, 93, 96], that is not shared by their male counterparts. This gender roles and social expectations might influence perceptions of health and prioritization of medical care, making women feel compelled to prioritize the needs of others over their own health. Lack of social support, disease awareness, work conflicts, personal health beliefs or perception of exercise as tiring or painful, might take part as well in the lower adherence to the programs.

In line with the guideline recommended care, this gender bias in the use of CR programs is consistent with the integration of other health measures recommended in the guidelines into daily life, such as, dietary changes (reducing fat intake) or engaging with physical activity. The study by Vynckier et al. [114] provides an overview on lifestyle advice given by health professionals and patients' attempts to implement it. When considering in particular actions to adopt a healthier diet, it appears that women are more likely to adopt changes such as salt and calorie reduction but are less likely to be advised to lose weight by participating in physical activity. In addition, it has been widely reported that women are less likely to comply with physical activity recommendations and are less likely to be considered active [69, 70, 78, 90]. Gender stereotypes may lead to women having fewer opportunities or incentives to participate in certain types of physical activity. In fact, being a woman is considered an independent risk factor for physical inactivity [115]. Women face additional workloads and family responsibilities, which limits the time to engage in exercise. Therefore, family and work demands may affect women's ability to incorporate physical activity into their daily routine. Also, the prioritization of other activities (caring for family members) may cause physical exercise to be relegated to the background [114]. Thus, while there is a concern to change eating habits, this is not enough if it is not accompanied by an increase in physical exercise and appropriate health care.

The differences in terms of pharmacological treatment are well documented, from women receiving more obsolete and less current treatment BBs, antiplatelet, second antiplatelet agent, anticoagulation, and statins…) instead of guideline-based medical therapy, to less intensive treatment and lower dosage. The reasons of this inequity, however, remained uncertain [35, 68, 105]. Another study by Vynckier [100] suggests that reduced awareness and underestimation of CVD risk in women might lead to underdiagnosis and undertreatment. The lack of evidence-based guidelines for women and the historical predominance of male participants and women underrepresentation in clinical trials would exacerbate these gender differences. This lack of scientific evidence for women may influence treatment decisions, preventing interventions and treatments from being equally effective for women and men. Barrett et al. added the perception of physicians and patients that women are at lower risk of severe CVD outcomes than men [25]. Furthermore, women are proven to be less adherent to therapeutical treatment than men. Reasons for this might be related to socioeconomic and cultural factors or barriers in access to health care as discussed before [74], that might influence patient adherence as well as prescription decisions in health care professionals. Lack of insurance has been reported as a risk of medication non-adherence [26, 40, 74]. However, prescription by a cardiologist or at hospital discharge has been shown to be a predictor of adherence [25]. This is especially important for statin treatment, as women often express concerns about side effects and a preference for diet or natural remedies and tend to abandon or refuse treatment [74].

Although this scoping review used a rigorous and thorough search strategy, limitations exist. Only peer reviewed articles written in English and Spanish were included in the review. This may have prevented the location of other relevant articles. Our selected search timeline of 2014–2023 could have eliminated other pertinent articles from being identified. However, to discuss gender inequities according to guideline recommendations and potential solutions to reduce them, we consider important to gain insight on the most recent secondary prevention interventions shown in the literature. Another possible limitation could be a publication bias in the literature, whereby studies that shown gender inequities are more likely to be published than those that find no differences.

Every effort was made to identify the various terms used to discuss gender equity and secondary prevention of CVD interventions in the literature to locate relevant articles, both in thesaurus vocabulary and free terms. However, it is possible that some relevant articles that did not include these common terms were excluded. Finally, this scoping review did not provide quality assessment of included studies. Indeed, due to the wide variety of studies found, this review aims to summarise current knowledge, identify gaps, discuss, and find potential measures to reduce gender inequity in secondary prevention of CVD, rather than to assess the quality of the included studies.

Conclusions

Performing this scoping review allowed us to compile and summarise the existing knowledge regarding the presence of gender inequalities on the secondary prevention of CVD. It also allowed us to propose ways to focus secondary prevention interventions to mitigate these inequalities. Additional research is required to delve into various factors influencing therapeutic disparities, non-participation, or dropout from CR programs, among other aspects. However, our findings underscore the importance of incorporating a gender perspective into evidence-based interventions for CVD secondary prevention. Thus, it is important to develop different strategies to specifically address gender inequalities in health care and the different needs, fears or preferences that men and women might have after a cardiovascular event to reach, assess and treat them in the better way. This will improve existing knowledge about the presentation and treatment of CVD in men and women. This approach is crucial to ensure the most equitable and effective attention to this issue.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Change history

10 August 2024

The authors first family name was wrongly captured as middle names. Now the author names have been corrected.

Abbreviations

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- BP:

-

Blood Pressure

- CR:

-

Cardiac Rehabilitation

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- MACE:

-

Major cardiovascular event

- LDL-C:

-

(Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- HbA1C:

-

Haemoglobin A1c

- BBs:

-

Beta blockers

- ACE-I:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

- ARBs:

-

Or angiotensin receptor blockers

- CVRFs:

-

Cardiovascular risk factors

References

World Health Organization. World Health Organization: newsroom, cardiovascular disease (CVDs). 2021 . Available from: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds Cited 2023 May 20.

European Heart Network, European Society of Cardiology. Fighting cardiovascular disease - a blueprint for EU Action. Brussels. 2020. Available from: https://www.escardio.org/static-file/Escardio/Advocacy/Documents/2020/ESC-EHN-blueprint_digital/edition.pdf

Mendis S, Puska P, Norrving B. Global atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control. WHO. World Heart Federation and World Stroke Organization. 2011.

Eruostat . Brussels: European statistics explained; 2024. Deaths from cardiovascular disease statistics; [data extracted in September 2023] Available at: https://www.ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Cardiovascular_diseases_statistics. Cited 28 June 2024.

Hyun K, Negrone A, Redfern J, Atkins E, Chow C, Kilian J, et al. Gender difference in secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease and outcomes following the survival of acute coronary syndrome. Hear Lung Circ. 2021;30(1):121–7.

Perel P, Avezum A, Huffman M, Pais P, Rodgers A, Vedanthan R, et al. Reducing Premature Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality in People With Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease The World Heart Federation Roadmap for Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Glob Heart. 2015;10(2):99–110.

Karunathilake SP, Ganegoda GU. Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases and Application of Technology for Early Diagnosis. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:5767864. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/5767864.

World Health Organization. Gender and Health. 2022 . Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/gender#tab=tab_1. Cited 2023 Sept 18.

Baggio G, Corsini A, Floreani A, Giannini S, Zagonel V. Gender medicine: A task for the third millennium. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2013;51(4):713–27.

Legato MJ. Gender-specific physiology: how real is it? How important is it? I Int J FertilWomens Med. 1997;42:19–29.

Shaw LJ, Pepine CJ, Xie J, Mehta PK, Morris AA, Dickert NW, et al. Quality and Equitable Health Care Gaps for Women: Attributions to Sex Differences in Cardiovascular Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(3):373–88.

Leurent G, Garlantézec R, Auffret V, Hacot JP, Coudert I, Filippi E, et al. Gender differences in presentation, management and inhospital outcome in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: Data from 5000 patients included in the ORBI prospective French regional registry. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;107(5):291–8.

Elgendy IY, Wegermann ZK, Li S, Mahtta D, Grau-Sepulveda M, Smilowitz NR, et al. Sex Differences in Management and Outcomes of Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients Presenting With Cardiogenic Shock. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15(6):642–52.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

López-Ferreruela, Aguilar-Palacio I, Malo S, Rabanaque M. Gender inequalities in secondary prevention of major cardiovascular events: a scoping review protocol. Inplasy Protocol. 202350084. https://doi.org/10.37766/inplasy2023.5.0084.

Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco A, Khalil H. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E, Z M, editors. Joanne Briggs Institute (JBI) Manual for Evidence Synthesis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12.

Clark JM, Sanders S, Carter M, Honeyman D, Cleo G, Auld Y, et al. Improving the translation of search strategies using the polyglot search translator: A randomized controlled trial. J Med Libr Assoc. 2020;108(2):195–207.

Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software. Australia. Available from: www.covidence.org.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):1–10.

Yu B, Zhao S, Hu D, Ambegaonakr BM. Gender differences in lipid goal attainment among Chinese patients with coronary heart disease: Insights from the DYSlipidemia International Study of China. Eur Hear Journal, Suppl. 2015;17:B39–46.

Abrahamyan L, Sahakyan Y, Wijeysundera HC, Krahn M, Rac VE. Gender Differences in Utilization of Specialized Heart Failure Clinics. J Women’s Heal. 2018;27(5):623–9.

Angus JE, Dale CM, Seto L, Kramer-kile M, Lapum J, Pritlove C, et al. Social Science & Medicine Gender matters in cardiac rehabilitation and diabetes : Using Bourdieu ’ s concepts. Soc Sci Med. December 2017;2018(200):44–51.

Arora S, Stouffer GA, Kucharska-Newton AM, Qamar A, Vaduganathan M, Pandey A, et al. Twenty Year Trends and Sex Differences in Young Adults Hospitalized with Acute Myocardial Infarction: The ARIC Community Surveillance Study. Circulation. 2019;139(8):1047–56.

Ballo P, Balzi D, Barchielli A, Turco L, Franconi F, Zuppiroli A. Gender differences in statin prescription rates, adequacy of dosing, and association of statin therapy with outcome after heart failure hospitalization: A retrospective analysis in a community setting. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;72(3):311–9.

Barrett E, Paige E, Welsh J, Korda RJ, Joshy G, Martin M, et al. Differences between men and women in the use of preventive medications following a major cardiovascular event: Australian prospective cohort study. Prev Med Reports. 2021;22: 101342.

Bhuyan SS, Shiyanbola O, Kedia S, Chandak A, Wang Y, Isehunwa OO, et al. Does Cost-Related Medication Nonadherence among Cardiovascular Disease Patients Vary by Gender? Evidence from a Nationally Representative Sample. Women’s Heal Issues. 2017;27(1):108–15.

Bird CE, Manocchia M, Tomblin B, Payne P, Kulakodlu M, Iacolo E, et al. Mapping the Gaps: Gender Differences in Preventive Cardiovascular Care among Managed Care Members in Four Metropolitan Areas. Women’s Heal Issues. 2018;28(5):446–55.

Birkemeyer R, Schneider H, Rillig A, Ebeling J, Akin I, Kische S, et al. Do gender differences in primary PCI mortality represent a different adherence to guideline recommended therapy? A multicenter observation BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014;14:1–7.

Blumer V, Greene SJ, Wu A, Butler J, Ezekowitz JA, Lindenfeld JA, et al. Sex Differences in Clinical Course and Patient-Reported Outcomes Among Patients Hospitalized for Heart Failure. JACC Hear Fail. 2021;9(5):336–45.

Carcel C, Wang X, Sandset EC, Delcourt C, Arima H, Lindley R, et al. Sex differences in treatment and outcome after stroke: Pooled analysis including 19,000 participants. Neurology. 2019;93(24):E2170–80.

Carlson B, Hoyt H, Kunath J, Bratzke LC. Gender Differences in Hispanic Patients of Mexican Origin Hospitalized with Heart Failure. Women’s Heal Issues. 2020;30(5):384–92.

Cewers E, Joensson A, Weinstein JM, Ben Gal T, Jaarsma T. Physical activity recommendations for patients with heart failure based on sex: A qualitative interview study. J Rehabil Med. 2019;51(7):532–8.

Cho KI, Shin E-S, Ann SH, Garg S, Her A-Y, Kim JS, et al. Gender differences in risk factors and clinical outcomes in young patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(11):1057–64.

Colbert JD, Martin BJ, Haykowsky MJ, Hauer TL, Austford LD, Arena RA, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation referral, attendance and mortality in women. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22(8):979–86.

Dagan M, Dinh DT, Stehli J, Tan C, Brennan A, Warren J, et al. Sex disparity in secondary prevention pharmacotherapy and clinical outcomes following acute coronary syndrome. Eur Hear J - Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2022;8(4):420–8.

Davis M, Diamond J, Montgomery D, Krishnan S, Eagle K, Jackson E. Acute coronary syndrome in young women under 55 years of age: clinical characteristics, treatment, and outcomes. Clin Res Cardiol. 2015;104(8):648–55.

De Smedt D, De Bacquer D, De Sutter J, Dallongeville J, Gevaert S, De Backer G, et al. The gender gap in risk factor control: Effects of age and education on the control of cardiovascular risk factors in male and female coronary patients. the EUROASPIRE IV study by the European Society of Cardiology. Int J Cardiol. 2016;209:284–90.

DeFilippis EM, Collins BL, Singh A, Biery DW, Fatima A, Qamar A, et al. Women who experience a myocardial infarction at a young age have worse outcomes compared with men: The mass general brigham YOUNG-MI registry. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(42):4127–37.

Dhruva SS, Dziura J, Bathulapalli H, Rosman L, Gaffey AE, Davis MB, et al. Gender Differences in Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy for Cardiovascular Disease Among Young Veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(3):806–15.

Eindhoven DC, Hilt AD, Zwaan TC, Schalij MJ, Borleffs CJW. Age and gender differences in medical adherence after myocardial infarction: Women do not receive optimal treatment – The Netherlands claims database. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;25(2):181–9.

El Missiri AM, Awadalla HM, Almoudi MM. Gender differences among ischemic heart disease patients enrolled in a cardiac rehabilitation program. Egypt Hear J. 2020;72(15). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43044-020-00052-6.

Eriksson M, Åsberg S, Sunnerhagen KS, Von Euler M. Sex Differences in Stroke Care and Outcome 2005–2018: Observations From the Swedish Stroke Register. Stroke. 2021;52(10):3233–42.

Gómez-Barrado JJ, Ortiz C, Gómez-Turégano M, Gómez-Turégano P, Garcipérez-de-Vargas FJ, Sánchez-Calderón P. Control lipídico en pacientes con enfermedad coronaria del Área de Salud de Cáceres (España): estudio LIPICERES. Clin e Investig en Arterioscler. 2017;29(1):13–9.

Gravely S, Anand SS, Stewart DE, Grace SL. Effect of referral strategies on access to cardiac rehabilitation among women. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21(8):1018–25.

Gutiérrez AG, Poblador-Plou B, Prados-Torres A, Laiglesia FJR, Gimeno-Miguel A. Sex differences in comorbidity, therapy, and health services’ use of heart failure in Spain: Evidence from real-world data. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6).

Hambraeus K, Tydén P, Lindahl B. Time trends and gender differences in prevention guideline adherence and outcome after myocardial infarction: Data from the SWEDEHEART registry. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23(4):340–8.

Hassanein M, Abdelhamid M, Ibrahim B, Sobhy M, Nasr G, Aboleineen MW, et al. Gender differences in Egyptian patients hospitalized with heart failure: insights from the European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. ESC Hear Fail. 2018;5(6):1159–64.

Höhn A, Gampe J, Lindahl-Jacobsen R, Christensen K, Oksuyzan A. Do men avoid seeking medical advice? A register-based analysis of gender-specific changes in primary healthcare use after first hospitalisation at ages 60+ in Denmark. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020;74(7):573–9.

Hopstock LA, Eggen AE, Løchen M-L, Mathiesen EB, Njølstad I, Wilsgaard T. Secondary prevention care and effect: Total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and lipid-lowering drug use in women and men after incident myocardial infarction – The Tromsø Study 1994–2016. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;17(6):563–70.

Hopstock LA, Eggen AE, Lochen ML, Mathiesen EB, Nilsen A, Njolstad I, et al. Blood pressure target achievement and antihypertensive medication use in women and men after first-ever myocardial infarction: The Tromsø Study 1994–2016. Open Hear. 2018;5(1):1–6.

Humphries KH, Lee MK, Izadnegahdar M, Gao M, Holmes DT, Scheuermeyer FX, et al. Sex Differences in Diagnoses, Treatment, and Outcomes for Emergency Department Patients With Chest Pain and Elevated Cardiac Troponin. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;25(4):413–24.

Hwan Kim Y, So W-Y. Gender differences in home-based cardiac rehabilitation of post- percutaneous coronary intervention patients. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019;31(2):249–55.

Jackson AM, Zhang R, Findlay I, Robertson K, Lindsay M, Morris T, et al. Healthcare disparities for women hospitalized with myocardial infarction and angina. Eur Hear J - Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2020;6(2):156–65.

Jortveit J, Govatsmark RE, Langørgen J, Hole T, Mannsverk J, Olsen S, et al. Gender differences in the assessment and treatment of myocardial infarction. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2016;136(14–15):1215–22.

Kerola AM, Palomäki A, Rautava P, Kytö V. Less revascularization in young women but impaired long-term outcomes in young men after myocardial infarction. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022;29(10):1437–45.

Khadanga S, Gaalema DE, Savage P, Ades PA. Under-utilization of Cardiac Rehabilitation in Women: Barriers and Solutions. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2022;41(4):207–13.

Khan E, Brieger D, Amerena J, Atherton JJ, Chew DP, Farshid A, Ilton M, Juergens CP, Kangaharan N, Rajaratnam R, Sweeny A, Walters DL, Chow CK. Differences in management and outcomes for men and women with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Med J Aust. 2018;209(3):118–23.

Khraishah H, Alahmad B, Alfaddagh A, Jeong SY, Mathenge N, Kassab MB, et al. Sex disparities in the presentation, management and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndrome: insights from the ACS QUIK trial. Open Hear. 2021;8(1).

Koçyiğit D, Tokgözoğlu L, Kayıkçıoğlu M, Altay S, Aydoğdu S, Barçın C, et al. Is there a gender gap in secondary prevention of coronary artery disease in Turkey? Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2018;46(8):683–91.

Ladapo JA, Pfeifer JM, Pitcavage JM, Williams BA, Choy-Shan AA. Quantifying Sex Differences in Cardiovascular Care among Patients Evaluated for Suspected Ischemic Heart Disease. J Women’s Heal. 2019;28(5):698–704.

Lauffenburger JC, Robinson JG, Oramasionwu C, Fang G. Racial/ethnic and gender gaps in the use of and adherence to evidence-based preventive therapies among elderly medicare part d beneficiaries after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2014;129(7):754–63.

Lee CMY, Mnatzaganian G, Woodward M, Chow CK, Sitas F, Robinson S, et al. Sex disparities in the management of coronary heart disease in general practices in Australia. Heart. 2019;105(24):1898–904.

Lee CY, Ting KL, Lu HT, Ali RM, Fong AYY, Wan Ahmad WA. Sex and gender differences in presentation, treatment and outcomes in acute coronary syndrome, a 10 year study from a multi-ethnic Asian population: The Malaysian National Cardiovascular Disease Database-Acute Coronary Syndrome (NCVD-ACS) registry. PLoS One. 2021;16(2 February):1–23.

Leung Yinko SSL, Maheswaran J, Pelletier R, Bacon SL, Daskalopoulou SS, Khan NA, et al. Sex differences in health behavior change after premature acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J. 2015;170(2):242-248.e3.

Lin CF, Shen LJ, Hsiao FY, Gau CS, Wu FLL. Sex differences in the treatment and outcome of patients with acute coronary syndrome after percutaneous coronary intervention: A population-based study. J Women’s Heal. 2014;23(3):238–45.

Lu Y, Zhou S, Dreyer RP, Caulfield M, Spatz ES, Geda M, et al. Sex differences in lipid profiles and treatment utilization among young adults with acute myocardial infarction: Results from the VIRGO study. Am Heart J. 2017;183:74–84.

M.T. Gürgöze, O.P. van der Galiën, M.A.M. Limpens, S. Roest, R.C. Hoekstra, A.S. IJpma, J.J. Brugts OCM and EB. Impact of sex differences in co‐morbidities and medication adherence on outcome in 25 776 heart failure patients. ESC Hear Fail. 2021;8:63–73.

Madika AL, Lemesle G, Lamblin N, Meurice T, Tricot O, Mounier-Vehier C, et al. Gender differences in clinical characteristics, medical management, risk factor control, and long-term outcome of patients with stable coronary artery disease: From the CORONOR registry. Panminerva Med. 2019;61(4):432–8.

Maleki A, Haghjoo M, Ghaderi M. The impact of gender differences on healthy lifestyle and its subscales among patients with coronary artery disease. Res Cardiovasc Med. 2016;5(4).

Minges KE, Strait KM, Owen N, Dunstan DW, Camhi SM, Lichtman J, et al. Gender differences in physical activity following acute myocardial infarction in adults : A prospective, observational study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017;24(2):192–203.

Moaddab F, Ghanbari A, Taheri-Ezbarami Z, Salari A, Kazemnezhad-Leyli E. Clinical parameters and outcomes in heart failure patients based on gender differences. Int J Africa Nurs Sci. 2023;18: 100525.

Naicker K, Liddy C, Singh J, Taljaard M, Hogg W. Quality of cardiovascular disease care in Ontario’s primary care practices: a cross sectional study examining differences in guideline adherence by patient sex. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:123. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-15-123.

Nakano A, Egstrup K, Svendsen ML, Schjødt I, Jakobsen L, Mehnert F, et al. Age- and sex-related differences in use of guideline-recommended care and mortality among patients with incident heart failure in Denmark. Age Ageing. 2016;45(5):635–42.

Nanna MG, Wang TY, Xiang Q, Goldberg AC, Robinson JG, Roger VL, et al. Sex Differences in the Use of Statins in Community Practice: Patient and Provider Assessment of Lipid Management Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(8):1–10.

Norberg H, Pranic V, Bergdahl E, Lindmark K. Differences in medical treatment and clinical characteristics between men and women with heart failure – a single-centre multivariable analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(4):539–46.

Okunrintemi V, Valero-Elizondo J, Patrick B, Salami J, Tibuakuu M, Ahmad S, et al. Gender differences in patient-reported outcomes among adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(24).

Oosenbrug E, Marinho P, Zhang J, Marzolini S, Colella TJF, Pakosh M, et al. Systematic Review / Meta-analysis Sex Differences in Cardiac Rehabilitation Adherence : A Meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2016;13–5.

Perera S, Aslam A, Stehli J, Kaye D, Layland J, Nicholls SJ, et al. Gender Differences in Healthy Lifestyle Adherence Following Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Coronary Artery Disease. Hear Lung Circ. 2021;30(1):e37-40.

Peters SAE, Colantonio LD, Zhao H, Bittner V, Dai Y, Farkouh ME, et al. Sex Differences in High-Intensity Statin Use Following Myocardial Infarction in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(16):1729–37.

Rachamin Y, Grischott T, Rosemann T, Meyer MR. Inferior control of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in women is the primary sex difference in modifiable cardiovascular risk: A large-scale, cross-sectional study in primary care. Atherosclerosis. 2021;324:141–7.

Rahman MA, Edward K, Mnsc LM, Llb SM, Wilson A, Worrall-carter L. Is There any Gender Difference for Smoking Persistence or Relapse Following Diagnosis or Hospitalization for Coronary Heart Disease ? Evidence From a Systematic Review and. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(6):1399–407.

Rangaiah SKK, Kaur S, Sidhu NS, Ramesh D, Veerappa K, Manjunath CN. Sex differences in acute coronary syndrome: Insights from an observation study in low socio-economic cohort from India. Future Cardiol. 2021;17(2):329–36.

Redfors B, Angerås O, Råmunddal T, Petursson P, Haraldsson I, Dworeck C, et al. Trends in Gender Differences in Cardiac Care and Outcome After Acute Myocardial Infarction in Western Sweden: A Report From the Swedish Web System for Enhancement of Evidence-Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEH. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(7):1–11.

Resurrección DM, Moreno-Peral P, Gómez-Herranz M, Rubio-Valera M, Pastor L, de Almeida JM, et al. Factors associated with non-participation in and dropout from cardiac rehabilitation programmes: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;18(1):38–47.

Resurrección DM, Motrico E, Rubio-Valera M, Mora-Pardo JA, Moreno-Peral P. Reasons for dropout from cardiac rehabilitation programs in women: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0200636.

Resurrección DM, Motrico E, Rigabert A, Rubio-Valera M, Conejo-Cerón S, Pastor L, et al. Barriers for Nonparticipation and Dropout of Women in Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs: A Systematic Review. J Women’s Heal. 2017;26(8):849–59.

Roth DL, Sheehan OC, Huang J, Rhodes JD, Judd SE, Kilgore M, et al. Medicare claims indicators of healthcare utilization differences after hospitalization for ischemic stroke: Race, gender, and caregiving effects. Int J Stroke. 2016;11(8):928–34.

Sakata Y, Miyata S, Nochioka K, Miura M, Takada T, Tadaki S, et al. Gender differences in clinical characteristics, treatment and long-term outcome in patients with stage C/D heart failure in Japan: Report from the chart-2 study. Circ J. 2014;78(2):428–35.

Samayoa L, Grace SL, Gravely S, Scott B, Marzolini S, Colella TJF. Systematic Review / Meta-analysis Sex Differences in Cardiac Rehabilitation Enrollment : A Meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30(7):793–800.

Setny M, Jankowski P, Kaminski K, Gasior Z, Haberka M, Czarnecka D, et al. Secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in Poland: does sex matter? Results from the POLASPIRE survey. Polish Arch Intern Med. 2022;132(3):22.

Setny M, Jankowski P, Krzykwa A, Kamiński KA, Gąsior Z, Haberka M, et al. Management of dyslipidemia in women and men with coronary heart disease: Results from polaspire study. J Clin Med. 2021;10(12):1–13.

Shehab A, Bhagavathula AS, Alhabib KF, Ullah A, Suwaidi JA, Almahmeed W, et al. Age-Related Sex Differences in Clinical Presentation, Management, and Outcomes in ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction Pooled Analysis of 15 532 Patients From 7 Arabian Gulf Registries. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(4):1–11.

Smith JR, Thomas RJ, Bonikowske AR, Hammer SM, Olson TP. Sex Differences in Cardiac Rehabilitation Outcomes. Circ Res. 2022;130(4):552–65.

Sobers N, Rose AMC, Samuels TA, Critchley J, Abed M, Hambleton I, et al. Are there gender differences in acute management and secondary prevention of acute coronary syndromes in Barbados? A cohort study BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):1–8.

Sotorra-Figuerola G, Ouchi D, García-Sangenís A, Giner-Soriano M, Morros R. Pharmacological treatment after acute coronary syndrome: Baseline clinical characteristics and gender differences in a population-based cohort study. Aten Primaria. 2022;54(1):102157.

Supervía M, Medina-Inojosa JR, Yeung C, Lopez-Jimenez F, Squires RW, Pérez-Terzic CM, et al. Cardiac Rehabilitation for Women: A Systematic Review of Barriers and Solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(4):565–77.

Tan YC, Sinclair H, Ghoorah K, Teoh X, Mehran R, Kunadian V. Gender differences in outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome in the current era: A review. Eur Hear J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2016;5(7):51–60.

Turk-Adawi KI, Oldridge NB, Vitcenda MJ, Tarima SS, Grace SL. Secondary Prevention Recommendation Attainment with Cardiac Rehabilitation: Is There a Gender Disparity? Women’s Heal Issues. 2016;26(3):278–87.

Victor BM, Teal V, Ahedor L, Karalis DG. Gender differences in achieving optimal lipid goals in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(10):1611–5.

Virani SS, Woodard LD, Ramsey DJ, Urech TH, Akeroyd JM, Shah T, et al. Gender disparities in evidence-based statin therapy in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(1):21–6.

Vynckier P, Ferrannini G, Rydén L, Tokgözoğlu L, Bruthans J, Kotseva K, et al. Medical Treatment in Coronary Patients: Is there Still a Gender Gap? Results from European Society of Cardiology EUROASPIRE V Registry. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2021;35(4):801–8.

Vynckier P, Ferrannini G, Ryden L, Jankowski P, De Backer T, Gevaert S, et al. Gender gap in risk factor control of coronary patients far from closing: Results from the European Society of Cardiology EUROASPIRE V registry. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022;29(2):344–51.

Wei J, Mehta PK, Grey E, Garberich RF, Hauser R, Bairey Merz CN, et al. Sex-based differences in quality of care and outcomes in a health system using a standardized STEMI protocol. Am Heart J. 2017;191(January):30–6.

Wilkinson C, Bebb O, Dondo TB, Munyombwe T, Casadei B, Clarke S, et al. Sex differences in quality indicator attainment for myocardial infarction: A nationwide cohort study. Heart. 2019;105(7):516–23.

Xia S, Du X, Guo L, Du J, Arnott C, Lam CSP, et al. Sex Differences in Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in China. Circulation. 2020;141(7):530–9.

Zhang H, Plutzky J, Shubina M, Turchin A. Drivers of the sex disparity in statin therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: A cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(5):1–13.

Zhao M, Vaartjes I, Graham I, Grobbee D, Spiering W, Klipstein-Grobusch K, et al. Sex differences in risk factor management of coronary heart disease across three regions. Heart. 2017;103(20):1587–94.

Zhao M, Woodward M, Vaartjes I, Millett ERC, Klipstein-Grobusch K, Hyun K, et al. Sex differences in cardiovascular medication prescription in primary care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(11).

Zheng H, Foo LL, Tan HC, Richards AM, Chan SP, Lee CH, et al. Sex Differences in 1-Year Rehospitalization for Heart Failure and Myocardial Infarction After Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2019;123(12):1935–40.

Dobbels F, Van Damme-Lombaert R, Vanhaecke J, De Geest S. Growing pains: non-adherence with the immunosuppressive regimen in adolescent transplant recipients. Pediatr Transplant. 2005;9(3):381–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3046.2005.00356.x.

Venditti V, Bleve E, Morano S, Filardi T. Gender-Related Factors in Medication Adherence for Metabolic and Cardiovascular Health. Metabolites. 2023;13(1087):1–26.

Greenwood BN, Carnahan S, Huang L. Patient–physician gender concordance and increased mortality among female heart attack patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(34):8569–74.

Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, Orav J, Blumenthal DM, Jha AK. Comparison of Hospital Mortality and Readmission Rates for Medicare Patients Treated by Male vs Female Physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):206–13.

Vynckier P, Ferrannini G, Kotseva K, Gevaert S, De Bacquer D, De Smedt D. Gender differences in lifestyle management among coronary patients and the association with education and age: Results from the ESC EORP EUROASPIRE v registry. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2022;21(7):717–23.

O’Neil A, Scovelle AJ, Milner AJ, Kavanagh A. Gender/sex as a social determinant of cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2018;137(8):854–64.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study has been funded by Health Institute Carlos III (ISCIII) through the research grants FIS PI22/01193 and co-financed by the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) “A way of making Europe”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ILF and IAP developed the scoping review search strategy and inclusion and exclusion criteria. SMF, MRH and BOA provided feedback on the review search strategy, suggested changes as appropriate. ILF ran the database searches. ILF and IAP screened articles (first and full-text screening) and SMF reviewed any articles where inclusion consensus was not reached by ILF and IAP. ILF and IAP charted relevant data and summarized key findings. SMF was the second reviewer for the articles. MJR and BOA also approved all articles included in this scoping review. ILF and IAP interpreted and discussed the results. ILF prepared the first draft of the manuscript. BOA made important contributions to the discussion of the results and the conclusions. MJR and SMF made important contributions to the revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to revising and approving the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

López Ferreruela, I., Obón Azuara, B., Malo Fumanal, S. et al. Gender inequalities in secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a scoping review. Int J Equity Health 23, 146 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-024-02230-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-024-02230-3