Abstract

Background

Oral diseases disproportionately affect poorer and disadvantaged groups of society. Despite this, there is scarce evidence regarding the monitoring of the structural determinants of health and their impact on oral health status. Thus, this systematic review addresses the question: Is oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) of elderly persons (aged ≥ 60 years) associated with structural determinants of health?

Methods

The present systematic review of observational studies applied the following inclusion and exclusion criteria; inclusion criteria: participants living in the community aged ≥ 60 years, reporting OHRQoL using Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP), Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI) or Oral Impact Daily Profile (OIDP). Exclusion criteria: studies reporting outcomes of participants aged < 60 years and residing in long-term care facilities. Three electronic databases (i.e., Embase, MEDLINE via Pubmed and Scopus) were screened (last searched on 23rd August 2024). Quality assessment of the included studies was performed using the tailored quality assessment tool developed by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. Meta-analysis; the overall sum score of OHIP, GOHAI and OIDP were transformed on a scale of 0-100. Sub-group analyses were performed for OHRQoL sum scores stratified by the following variables: Country-level income, Gini index, unemployment rate, Human Development Index (HDI), out-of-pocket health expenditure, health expenditure per capita, prevalence of dental caries, edentulism and periodontal disease.

Results

The search identified 910 records. After deduplication, title, abstract and full-text review, 45 papers were included for data extraction. The highest OHRQoL sum scores were recorded in studies from countries with high-middle to high income (77.9, 95% CI 70.2–85.6), low Gini index (91.3, 95% CI 90.0-92.6), high to very high HDI (78.4, 95% CI 71.1–85.8) and lowest out-of-pocket expenditure (83.9, 95% CI 75.2–92.6). Countries with low dental caries prevalence reported higher OHRQoL compared to countries with high dental caries prevalence (81.5, 95% CI 76.5–86.6). Limitations include the fair quality of > 50% of the studies included and the high inter- study heterogeneity.

Conclusions

Structural determinants of health contribute to a good quality of life related to oral health. Upstream interventions are essential for improving oral health conditions and quality of life among older adults.

Registration

The review protocol was registered (CRD42024573590) with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Health and health equity are determined by the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, play and age, as well as by biological determinants [1]. Health equity refers to the absence of unfair and avoidable differences among groups of people and can be achieved when everyone is able to attain their full potential for health and well-being [1]. The term social determinants of health (SDOH) is often used to describe any nonmedical factors influencing health, including health-related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors. However, SDOH also encompass ‘upstream’ factors, such as social disadvantage, risk exposure, and social inequities that play a fundamental causal role in poor health outcomes, and thus represent important opportunities for improving health and reducing disparities [2]. The conceptual framework developed by the WHO’s Commission divides the SDOH into two categories: (i) the intermediary determinants, such as material circumstances, psychosocial circumstances, and behavioral and biological factors, (ii) the structural determinants, defined as SDOH inequities or the ‘root causes’ of health inequities [3] The structural determinants of health include governance, macroeconomic policies, social and public policy, culture and societal values, which generate social stratification and determine the socioeconomic positions of individuals within society [4]. These structural determinants influence income, working conditions, health care, health systems, housing, and education, experienced by individuals in their neighborhoods and communities [5]. Furthermore, they affect whether the resources necessary for health are distributed equally or unjustly across society, based on race, gender, social class, geography, sexual identity, or other socially defined categories [6]. There is, however, scarce evidence on monitoring the structural determinants of health [7].

Thus, experts have called upon the dental research community to generate evidence on the more complex upstream factors as oral diseases remain a major public health problem [8, 9], with 3.5 billion people worldwide affected by untreated dental caries, severe periodontitis, and edentulism [10, 11].

Oral diseases and oral health inequities have substantial effects on the individuals’ quality of life [12]. Oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) is a multidimensional construct that reflects people’s comfort in eating, sleeping, social interaction, self-esteem, and the satisfaction with their oral health and is associated with functional, psychological and social factors [13]. Measuring OHRQoL has shifted the focus from traditional assessments of oral health to a more comprehensive view of a person’s social, emotional, and physical functioning, helping define appropriate treatment goals and outcomes. The three most widely used dental patient reported outcome measures (dPROMs) [14] are Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) [15], the General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI) [16] and the Oral Impact on Daily Performances (OIDP) [17].

A study by Baker et al. found that children, aged 8 to 15 years, from different countries worldwide, had higher OHRQoL sum scores in countries with higher economic resources, lower inequalities and lower out-of-pocket health care expenditure [18]. Alwadi et al. found that adolescents living in areas with high-income inequalities (high Gini index) had poorer OHRQoL compared to those living in areas with lower-income inequalities [19]. While several studies have explored the impact of structural determinants on the oral health status and quality of life of children and adolescents, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no study has systematically investigated how these factors affect elderly individuals.

Given that population aging is occurring in nearly every country due to increasing life expectancy and declining birth rates, this rapidly growing age group represents a highly relevant population. Societal and economic policies, combined with functional decline and a high disease burden, make this group one of the most vulnerable in modern societies [20]. Addressing aging requires action on key factors to improve the quality of life of older individuals’ and ensure equity in old age [21]. However, no evidence currently exists regarding the influence of structural determinants of health on OHRQoL or how this may affect the daily lives of elderly individuals.

Given this gap in the literature, the present study aimed to assess potential associations between structural determinants of health, oral diseases, and OHRQoL in elderly individuals by systematically reviewing the literature.

Method

Protocol and registration

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline. The review protocol was registered (CRD42024573590) with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) system (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/).

The PECO tool was applied as follows:

P: participants aged ≥ 60 years. The cut-off of 60 years was based on the United Nations recommendations [22].

E: structural determinants of health: Country-level income, Gini index, unemployment rate, Human Development Index (HDI), out-of-pocket health expenditure, health expenditure per capita.

Dental status: dental caries, periodontal disease, edentulism.

C: not applicable.

O: OHRQoL measured by OHIP, GOHAI and OIDP.

Eligibility criteria

Observational studies including cross-sectional studies and longitudinal studies, as well as national oral health surveys, were screened for inclusion. Titles, abstracts and full texts were reviewed according to the following inclusion and exclusion criteria: participants of selected studies had to be aged ≥ 60 years living in the community, OHRQoL reported using OHIP, GOHAI or OIDP, studies conducted on a local/regional or national level. For longitudinal studies, participants had to be aged ≥ 60 years at baseline as only baseline OHRQoL scores were included (cross-sectional part of the longitudinal study). As the purpose of the systematic review was to analyse potential associations between the OHRQoL and structural determinants of health, only studies that included the number of study participants and the mean or median and standard deviation or interquartile range of the total OHRQoL sum scores were included.

Studies reporting the outcomes of participants aged < 60 years and recruited from settings other than the community e.g. dental clinics, hospital/university settings, residing in long-term care facilities were excluded from the study.

Search strategy

The following electronic databases Embase, MEDLINE via Pubmed and Scopus were screened with the search restricted to articles published from January 2014 onwards. As the variables taken to assess the structural determinants of health vary within the same country over the years, the search was restricted to the year 2014 to have the most recent data over the last 10 years. The following terms were used as Medical Subject Heading terms (MeSH) and keywords: “oral health”, “elderly”, “oral health-related quality of life” (Additional file, Sect. 1). Open Grey (http://www.opengrey.eu) was searched for grey literature and free-hand searches were carried out. The last search was performed in August 2024. No language restrictions were applied.

Study selection

The retrieved items were imported into EndNote X9 Version 3.3® (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA). After the removal of duplicate records, two authors (GC, RBB) independently examined the titles and abstracts, followed by full-text review. Two of the authors (GC, RBB) independently reviewed the papers and any disagreements were resolved through discussion. Where this was not possible, a third reviewer was consulted (CT). The systematic review was performed using the software Rayyan [23]. The kappa-statistic was calculated as a measure of interrater agreement between the two raters (RBB, GC) using StataSE18® (StataCorp LLC USA http://www.stata.com).

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction and quality assessment were performed independently by the review authors. After data extraction, one author (RBB) randomly selected 10% of the papers and checked the data entry fields for reliability. For each paper, the following data were collected whenever possible: title, author, year of publication, source, country, aim of the study, study design, participant characteristics i.e. age and gender, sample size, data reported on OHRQoL.

Quality assessment was performed using the tailored quality assessment tool developed by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools). The quality of the papers was recorded in two steps; the number of ‘yes’ scores, with ‘yes’ indicating a low risk of bias per question, graded as follows: 11–14 good quality, 7–10 fair quality, 0–6 poor quality, followed by an individual assessment of the potential risk of bias per study [24].

Structural determinants of health

-

Country level income: The World Bank’s income classifications divide countries into four categories based on their gross national income (GNI) per capita. GNI is the aggregate value of the gross balances of primary incomes for all sectors.

-

Gini index (measure of inequality): an index measuring the inequality in the distribution of family income, measured from 0 (no inequality) − 100 (maximum inequality) (https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/economic-inequality-gini-index) ( [25].

-

Unemployment rate: the number of people (aged 15 years or over) who are not in employment divided by the labour force multiplied by 100 [26]. (https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators).

-

HDI: a measure of life expectancy, education (mean age of schooling of adults aged > 25 years) and standard of living measured by the Gross National Income (https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/specific-country-data#/countries/).

-

Out-of-pocket expenditure: a percentage of current health care expenditure is the direct outlay by households for health care (https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators.

-

Per capita expenditure on health: the sum of private and public annual health expenditure per capita expressed in Purchasing Power Parities (PPP) (https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/annual-healthcare-expenditure-per-capita? tab=chart.

For further information on the categorization of these variables please refer to Additional file, Sect. 4.

Dental status variables

The prevalence of dental caries, periodontal disease, and edentulism was collected from the Global Burden of Disease data (https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/gbd), which was reported per country and year the study was conducted. These variables were dichotomised into low dental caries/periodontal disease/edentulism prevalence when studies reported dental caries, periodontal disease and/or edentulism prevalence below the overall mean prevalence, and into high prevalence category when studies reported prevalence above the overall mean prevalence.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis of the included studies was performed. As high OHIP and OIDP sum scores indicate poor OHRQoL while high GOHAI sum scores indicate good OHRQoL, the sum scores were transformed, so that all three OHRQoL sum scores follow the same direction i.e. high sum scores indicate high OHRQoL. Furthermore, the overall sum scores were transformed on a scale of 0-100 in order to allow the OHRQoL sum scores measured using the three different questionnaires to be combined into one meta-analysis [27, 28].with 100 indicating the highest possible OHRQoL.

As the main purpose of the meta-analyses performed was to assess relationships between the subgroups of the variables analysed and the OHRQoL sum scores, the overall pooled mean OHRQoL results are not presented. OHRQoL sum scores are analysed according to the following stratified variables: country-level income, HDI, Gini index, unemployment rate, out-of-pocket health expenditure, health expenditure per capita, prevalence of dental caries, edentulism and periodontal disease. Results are presented as forest plots per variable and statistically significant results are shown as follows: (*) statistical significance at the 90% level, (**) statistical significance at the 95% level, (***) statistical significance at the 99% level.

Heterogeneity was estimated using the I2 statistic and a 95% prediction interval. A random-effects model (REM) with a 95% confidence interval was chosen for the meta-analyses. To investigate heterogeneity, subgroup analysis and meta-regression were performed taking into consideration risk of bias of the studies (high vs. low risk), areas where the study was conducted (regional/national vs. local), the year when the study was conducted and the sample size. Sensitivity analysis was performed using the leave-out-one analysis. The leave-out-one analysis identifies outlier data. If outlier data are present, the overall pooled mean OHRQoL score would change if the outlier data were excluded from the meta-analysis [29]. Publication bias was evaluated by means of a funnel plot. Statistical analysis was carried out using StataSE18®.

Results

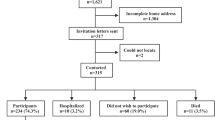

The search identified 910 papers. After deduplication, the titles and abstracts of 758 papers were reviewed, leaving 143 papers for full-text review. 98 studies were excluded after full-text analysis, resulting in 45 papers for data extraction (Fig. 1). The list of references excluded after full-text review and the reason for exclusion is available in Additional file, Sect. 2. Kappa score values for agreement between the two authors who assessed titles and abstracts and full-texts were 0.81, and 0.73, respectively.

Study characteristics

Thirty-nine studies were cross-sectional while six were longitudinal. Data were published in 25 different countries. The sample size ranged from 20 [30] – 6551 [31] participants. Twenty-one studies reported dPRO using GOHAI, 19 studies used OHIP-14, one study reported dPROs using OHIP-7 and two studies used OIDP. There was a range of OHRQoL transformed scores from 35 [32] to 95 [33,34,35]. The majority of studies used OHRQoL questionnaires previously validated in the country of use. Further details of the included studies can be found in Additional file, Sect. 3.

Risk of bias

Thirty-two studies were classified as being of fair quality. Seven and five studies were classified as being of good and poor quality, respectively (Additional file, Sect. 5). Lack of sample size justification or power analysis (Q5) in over 50% of the investigations affected the quality outcome of the papers (Additional File, Sect. 6).

Synthesis of results

Structural determinants of health

Statistically significant differences were found between the country-level income, Gini index, HDI, and out-of-pocket expenditure, and OHRQoL sum scores. Studies from countries with a low-middle income presented with the lowest OHRQoL sum scores (66.9, 95% CI 56.7–77.0) (Fig. 2a). Studies from countries with relative equality (Gini index 0.21–0.30) reported very high OHRQoL (91.3, 95% CI 90.0-92.6) (Fig. 2b). while similar OHRQoL sum scores were found among the other three Gini index categories (adequate equality 75.4 95% CI 70.1–82.7, high inequality 75.3 95% CI 67.1–83.6, severe inequality 81.2 95% CI 75.3–88.3). Studies from countries with a medium HDI reported the lowest OHRQoL sum score (63.5, 95% CI 54.3, 72.7) compared to countries with high (79.9, 95% CI 74.4–85.5) and very high HDI (78.4, 95% CI 71.1–85.8) (Fig. 2d). Studies from countries with the highest out-of-pocket expenditure had the lowest OHRQoL (67.5, 95% CI 58.5–76.5) compared to those with the lowest out-of-pocket expenditure (83.9, 95% CI 75.2–92.6) (Fig. 3a).

There was no statistically significant difference in OHRQoL based on unemployment rate (Fig. 2c), and per capita expenditure on health care (Fig. 3a).

Dental status

Dental caries prevalence had a statistically significant association with OHRQoL sum scores. The category with lower dental caries prevalence presented with a higher OHRQoL sum score (81.5, 95% CI 76.5–86.6) (Fig. 4a). There were no statistically significant differences reported in the OHRQoL sum scores based on periodontal disease prevalence and prevalence of edentulism (Fig. 4b and c).

Subgroup analysis, meta-regression and sensitivity analysis

Heterogeneity was high with a 95% prediction interval of 52.0-102.0 (overall pooled mean OHRQoL 77.0). Risk of bias of the studies accounted for 10% of the heterogeneity while the year the study was conducted, accounted for 4% of the heterogeneity. Sample size and whether the studies were conducted on a regional/national/local level did not explain heterogeneity (Additional file, Sect. 7). The sensitivity analysis did not identify any study which could have affected the overall results (Additional file, Sect. 8). The funnel plot shows asymmetry.(Additional file, Sect. 9).

Discussion

This systematic review identified associations between structural determinants of health, specifically country-level income and Gini index (macroeconomic policy), HDI (social policy), and out-of-pocket expenditure (public policy), and the OHRQoL of elderly individuals worldwide. Additionally, higher OHRQoL scores were observed in countries with a lower prevalence of dental caries. While previous studies have largely focused on children and adolescents when exploring the relationship between OHRQoL and structural determinants of health [18, 19, 36], the present review demonstrates that similar trends apply to elderly populations. Although this dynamic may be relevant across all age groups, older individuals face unique challenges due to their personal and demographic circumstances. Multi-morbidity and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are highly prevalent in this age group, leading to increased vulnerabilities resulting from the complex interplay of sociopolitical, economic, structural, cultural, and interpersonal factors [37].

Structural determinants have a cascading effect on intermediary determinants of health, including income, education, material circumstances, social relationships, psychosocial factors, and healthcare accessibility. These, in turn, influence proximal determinants such as nutrition, physical activity, and alcohol consumption, which affect both general and oral health outcomes [38].

Higher economic resources (high GDP and GNI) and reduced inequality (low Gini index) have been linked to improved population health [39]. Greater economic resources and equity facilitate increased investment in health and education. Consequently, high educational attainment, income, and life expectancy, as captured by the HDI, are likely contributors to better oral health and quality of life [18]. Education, in particular, plays a crucial role in improving health, as it is associated with better employment opportunities and higher income, which in turn influence healthier food choices, access to safe neighborhoods, and the availability of healthcare services [40]. A study across 12 European countries revealed disparities in the use of medical and dental services by education level among individuals aged 50 and over [41].

Dental care coverage varies significantly between and within countries, with various population subgroups receiving differing levels of access. While many countries provide free dental care to children, individuals with special needs, and residents in long-term care, such provisions often do not extend to older adults living independently in the community. Evidence indicates that financial barriers hinder dental service utilization among the elderly. Commonly cited barriers include high treatment costs and co-payments [42]. These financial constraints often result in problem-oriented dental visits rather than preventive care, contributing to poorer oral health, higher individual and systemic financial burdens, and lower OHRQoL [43].

One strength of the present systematic review is its extensive search strategy, which included multiple databases, grey literature, and hand searches without applying language restrictions. Nonetheless, data were unavailable for several countries, particularly low-income and low-HDI nations, likely due to the high costs and resource demands associated with conducting national-level studies.

However, the review has limitations. Over half of the included studies were rated as being of fair quality, which introduces bias. Additionally, heterogeneity across studies was high, and the asymmetry of the funnel plot suggests possible publication bias. High heterogeneity is, however, common in meta-analyses of observational studies, where true variability across settings and time periods is expected [44]. Regarding publication bias, it is important to note that the assumption that only studies with positive results are published may not hold true for observational studies, given the lack of consensus on what constitutes a “positive” result in this context [45]. Nevertheless, due to the comprehensive search strategy, including grey literature, the risk of missed publications is considered minimal.

This review underscores the necessity of combining downstream (individual-level), midstream (community-level), and upstream (population-level) interventions. Structural, or upstream, interventions addressing the underlying causes of poor oral health are essential for promoting oral health equity in elderly populations [46]. Many older individuals face significant barriers in accessing high-quality healthcare services.

Future efforts should focus on ensuring that affordable, quality, and accessible social services, including healthcare, are available to all older individuals [47]. One promising initiative is the integration of oral healthcare with NCD management, as recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) and already adopted by countries such as Thailand [48]. Evidence suggests that oral conditions like periodontal disease and dental caries share common risk factors with NCDs and may be bi-directionally associated [49]. Given the high prevalence of NCDs in the elderly, investment in integrated care may improve both general and oral health, reduce health disparities, enhance quality of life, and generate cost savings for healthcare systems [50].

The findings of this study also highlight the importance of incorporating dPROMs into observational research, including national oral health surveys [51]. These instruments provide a more comprehensive and person-centred assessment of oral health and are critical in evaluating the cost-effectiveness of clinical and public health interventions. They can also guide strategic planning aimed at improving global oral health [52].

A transdisciplinary approach, integrating insights from politics, economics, sociology, and environmental science with oral epidemiology, is essential for achieving better oral health and quality of life outcomes [5, 53].

Conclusion

Within the limitations of this systematic review, the present study demonstrates that structural determinants of health, including high economic resources, low levels of inequality, high human development, and reduced financial burdens on individuals, are associated with better OHRQoL in elderly populations. These findings underscore the importance of addressing upstream determinants through policies and interventions that extend beyond individual behaviors and healthcare access.

To improve the oral health and overall quality of life of older adults, it is essential to implement comprehensive public health strategies that include structural and societal reforms. Such interventions must aim to reduce inequalities, enhance health system financing, and integrate oral health with broader non-communicable disease frameworks. Addressing these systemic factors will not only promote oral health equity but also contribute to the well-being and dignity of aging populations globally.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- OHRQoL:

-

Oral Health-Related Quality of Life

- dPROs:

-

Dental Patient-Reported Outcomes

- dPROMs:

-

dental Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

- OHIP:

-

Oral Health Impact Profile

- GOHAI:

-

General Oral Health Assessment Index

- OIDP:

-

Oral Impact on Daily Performances

- GDP:

-

Gross Domestic Product

- HDI:

-

Human Development Index

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Health equity. Available from https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-equity#tab=tab_1 [Accessed May 28, 2025].

Bharmal N, Derose KP, Felician M, Weden MM. Understanding the upstream social determinants of health. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2015 May. [Accessed May 26, 2025].

Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Social Determinants of Health Discussion. Paper 2 (Policy and Practice). Published 2010. [Accessed May 26, 2025].

Broomhead T, Baker SR. From micro to macro: structural determinants and oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2023;51(1):85–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12803.

Lipshutz JA, Hall JE, Penman-Aguilar A, Skillen E, Naoom S, Irune I. Leveraging social and structural determinants of health at the centers for disease control and prevention: A Systems-Level opportunity to improve public health. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2022;28(2):E380–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001363.

Heller JC, Givens ML, Johnson SP, Kindig DA. Keeping it political and powerful: defining the structural determinants of health. Milbank Q. 2024;102(2):351–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12695.

Operational framework for monitoring social determinants of health equity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Peres MA, Macpherson LMD, Weyant RJ, Daly B, Venturelli R, Mathur MR, et al. Oral diseases: A global public health challenge. Lancet. 2019;394(10194249–260):249–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31146-8.

Watt RG, Daly B, Allison P, Macpherson LMD, Venturelli R, Listl S, et al. Ending the neglect of global oral health: time for radical action. Lancet. 2019;394(10194):261–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31133-X.

Kassebaum NJ, Smith AGC, Bernabé E, Fleming TD, Reynolds AE, Vos T, et al. Global, regional, and National prevalence, incidence, and Disability-Adjusted life years for oral conditions for 195 countries, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. J Dent Res. 2017;96(4):380–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034517693566.

Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. (2024). Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021). Seattle, WA: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). https://www.healthdata.org/gbd/2021. [Accessed May 28, 2025].

Watt RG, Sheiham A. Inequalities in oral health: A review of the evidence and recommendations for action. Br Dent J. 1999;187(1):6–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800191.

Sischo L, Broder HL. Oral health-related quality of life: what, why, how, and future implications. J Dent Res. 2011;90(11):1264–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034511399918.

Riva F, Seoane M, Reichenheim ME, Tsakos G, Celeste RK. Adult oral health-related quality of life instruments: A systematic review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2022;50(5):333–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12689.

Slade G, Spencer A. Development and evaluation of the oral health impact profile. Community Dent Health. 1994;11(1):3–11.

Atchison K, Dolan T. Development of the geriatric oral health assessment index. J Dent Educ. 1990;54(11):680–7.

Adulyanon S, Vourapukjaru J, Sheiham A. Oral impacts affecting daily performance in a low dental disease Thai population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1996;24:385–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0528.1996.tb00884.x.

Baker SR, Foster Page L, Thomson WM, Broomhead T, Bekes K, Benson PE, et al. Structural determinants and children’s oral health: A Cross-National study. J Dent Res. 2018;97(10):1129–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034518767401.

Alwadi MAM, Vettore MV. Contextual income inequality and adolescents’ oral-health-related quality of life: A multi-level analysis. Int Dent J. 2019;69(6):463–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/idj.12504.

National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. (2021). Oral health in America: Advances and challenges. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. Available from https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/oral-health-america. [Accessed May 26, 2025].

Venkatapuram S, Ehni HJ, Saxena A. Equity and healthy ageing. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(11):791–2. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.16.187609.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables. Working Paper No. ESA/P/WP/248. New York: United Nations. 2017. [Accessed May 28, 2025].

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan — a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Reviews. 2016;5(210). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4.

Borg-Bartolo R, Roccuzzo A, Molinero-Mourelle P, Schimmel M, Gambetta-Tessini K, Chaurasia A, et al. Global prevalence of edentulism and dental caries in middle-aged and elderly persons: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent. 2022;127:104335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2022.104335.

Teng F, He J, Pan X, Zhang C. Metric of carbon equity: carbon Gini index based on historical cumulative emission per capita. Adv Clim Change Res. 2011;2(3):134–40. https://doi.org/10.3724/sp.J.1248.2011.00134.

Sengenberger W. Beyond the measurement of unemployment and underemployment. The case for extending and amending labour market statistics. Int Labour Office. 2011. [Accessed May 26, 2025].

Schertel Cassiano L, Abdullahi F, Leite FRM, Lopez R, Peres MA, Nascimento GG. The association between halitosis and oral-health-related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2021;48(11):1458–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13530.

Hopkins WG, Rowlands DS. Standardization and other approaches to meta-analyze differences in means. Stat Med. 2024;43(16):3092–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.10114.

Burci L, Zanin S, Miguel O, Souza A, Dias J, Miguel M. Comparison of two oral health-related quality-of-life measures in elderly patients: the influence of missing teeth, and socio demographic factors [Comparação entre dois instrumentos de avaliação de qualidade de vida em pacientes idosos: A influência da perda de dentes e fatores sociodemográficos]. Brazilian Dent Sci. 2020;23(2):1–9. https://doi.org/10.14295/bds.2020.v23i2.1878.

Chimi Chimi ND, Onambele L. Oral Health-Related quality of life in adults in mbouda/cameroon 2020. J Food Technol Nutr Sci. 2021;3(4):1–7. https://doi.org/10.47363/JFTNS/2021(3)130.

Nanri H, Yamada Y, Itoi A, Yamagata E, Watanabe Y, Yoshida T, et al. Frequency of fruit and vegetable consumption and the oral health-related quality of life among Japanese elderly: A cross-sectional study from the Kyoto-Kameoka study. Nutrients. 2017;9(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9121362.

AlBaker AM, AlBaqami FF, AlHarbi TM, AlAmri MD, Baskaradoss JK. Oral health status and oral health-related quality of life among hospitalized and nonhospitalized geriatric patients. J Contemp Dent Pract 2017, 18(3):228–33. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10024-2022

Suphinwong C, Ong-Artborirak P, Chautrakarn S. Health behaviors, tooth number, and oral Health-Related quality of life among Thai older adults. J Int Dent Med Res. 2022;15(3):1248–53.

Masood M, Newton T, Bakri NN, Khalid T, Masood Y. The relationship between oral health and oral health related quality of life among elderly people in united Kingdom. J Dent 2017, 56:78–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2016.11.002

Tsakos G, Guarnizo-Herreño CC, O’connor R, Wildman J, Steele JG, Allen PF. Explaining time changes in oral health-related quality of life in england: A decomposition analysis. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2017;71(12):1203–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2017-209696.

Monsalves MJ, Espinoza I, Moya P, Aubert J, Duran D, Arteaga O, et al. Structural determinants explain caries differences among preschool children in chile’s metropolitan region. BMC Oral Health. 2023;23(1):136. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-023-02778-6.

Carroll C, Sworn K, Booth A, Tsuchiya A, Maden M, Rosenberg M. Equity in healthcare access and service coverage for older people: a scoping review of the conceptual literature. Integr Healthc J. 2022;4(1):e000092. https://doi.org/10.1136/ihj-2021-000092.

World Dental Federation (FDI). FDI Access to Oral Health Care White Paper [White paper]. Geneva. 2023. Available from: https://www.fdiworlddental.org/sites/default/files/2023-05/FDI%20Access%20to%20Oral%20Health%20Care%20White%20Paper.pdf. [Accessed May 28, 2025].

Ray D, Linden M. Health, inequality and income: a global study using simultaneous model. J Economic Struct. 2018;7(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40008-018-0121-3.

Perez FP, Perez CA, Chumbiauca MN. Insights into the social determinants of health in older adults. J Biomed Sci Eng. 2022;15(11):261–8. https://doi.org/10.4236/jbise.2022.1511023.

Marco T. Inequities in health care utilization by people aged 50+: evidence from 12 European countries. Soc Sci Med. 2015;126:154–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.028.

Beaven A, Marshman Z. Barriers and facilitators to accessing oral healthcare for older people in the UK: a scoping review. Br Dent J. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-7740-x.

Valdez RAG, Spinler K, Walther C, Kofahl C, Buczak-Stec E, Heydecke G, et al. Do postponed dental visits for financial reasons reduce quality of life? Evidence from the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33(2):437–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-020-01536-w.

Barker TH, Migliavaca CB, Stein C, Colpani V, Falavigna M, Aromataris E, Munn Z. Conducting proportional meta-analysis in different types of systematic reviews: a guide for synthesisers of evidence. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21(1):189. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-021-01381-z.

Metelli S, Chaimani A. Challenges in meta-analyses with observational studies. Evid Based Ment Health. 2020;23(2):83–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2019-300129.

Baelum V. Dentistry and population approaches for preventing dental diseases. J Dent. 2011;39(Suppl 2):S9–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2011.10.015.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Health Inequalities in Old Age. 2015. Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/ageing/wp-content/uploads/sites/24/2018/04/Health-Inequalities-in-Old-Age.pdf. [Accessed May 28, 2025].

Jiang CM, Chu CH, Duangthip D, Ettinger RL, Hugo FN, Kettratad-Pruksapong M, et al. Global perspectives of oral health policies and oral healthcare schemes for older adult populations. Front Oral Health. 2021;2:703526. https://doi.org/10.3389/froh.2021.703526.

Cardoso EM, Reis C, Manzanares-Cespedes MC. Chronic periodontitis, inflammatory cytokines, and interrelationship with other chronic diseases. Postgrad Med. 2018;130(1):98–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.2018.1396876.

Benzian H, Daar A, Naidoo S. Redefining the non-communicable disease framework to a 6 x 6 approach: incorporating oral diseases and sugars. Lancet Public Health. 2023;8(11):e899–904. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00205-0.

World Health Organisation. Oral health surveys basic methods. 5th ed. France: WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data; 2013.

FDI World Dental Federation. Oral health and quality of life. 2015. Available at: https://www.fdiworlddental.org/oral-health-and-quality-life. [Accessed May 28, 2025].

Dawson ER, Stennett M, Daly B, Macpherson LMD, Cannon P, Watt RG. Upstream interventions to promote oral health and reduce socioeconomic oral health inequalities: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2022;12(6):e059441. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059441.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Bernadette Rawyler and Ines Badertscher from the Graphic Department of the School of Dental Medicine, University of Bern, Switzerland for their work in the preparation of the figures.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RBB: Conceptualization, methodology, statistical analysis, writing original draft, AR: Methodology, writing original draft, KGT: Methodology, statistical analysis, writing original draft, MS: Methodology, writing- reviewing and editing, PMM: methodology, writing-reviewing and editing, GS: methodology, writing- reviewing and editing, MF: methodology, writing- reviewing and editing, MEO: methodology, writing – reviewing and editing, RAG: methodology, writing – reviewing and editing, CT: Methodology, writing- reviewing and editing, GC: conceptualization, methodology, statistical analysis, writing-reviewing and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Borg-Bartolo, R., Roccuzzo, A., Gambetta-Tessini, K. et al. Association between oral health-related quality of life and structural determinants of health among elderly populations. a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Equity Health 24, 189 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-025-02557-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-025-02557-5