Abstract

Background

Measuring self-reported experience of health and functioning is important for understanding the changes in the health status of individuals switching from cigarettes to less harmful tobacco and/or nicotine products (TNP) or reduced-risk products (RRP) and for supporting tobacco harm reduction strategies.

Methods

This paper presents insights from three research activities from the preparatory phase of the development of a new self-report health and functioning measure. A scoping literature review was conducted to identify the positive and negative impact of TNP use on health and functioning. Focus groups (n = 29) on risk perception and individual interviews (n = 40) on perceived dependence in people who use TNPs were reanalyzed in the context of health and functioning, and expert opinion was gathered from five key opinion leaders and five technical consultants.

Results

Triangulating the findings of the review of 97 articles, qualitative input from people who use TNPs, and expert feedback helped generate a preliminary conceptual framework including health and functioning and conceptually-related domains impacted by TNP use. Domains related to the future health and functioning measurement model include physical health signs and symptoms, general physical appearance, functioning (physical, sexual, cognitive, emotional, and social), and general health perceptions.

Conclusions

This preliminary conceptual framework can inform future research on development and validation of new measures for assessment of overall health and functioning impact of TNPs from the consumers’ perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

As a leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality worldwide, smoking remains a major public health problem. Compared with those who do not smoke, people who smoke are significantly more likely to develop heart diseases, lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and other diseases [1, 2]. It is well established that the best way to avoid the health risks associated with smoking is for people to never start and for those who smoke to quit [1, 3]. Tobacco harm reduction is one way to alleviate the health risk for individuals who choose not to quit smoking [4], by providing less harmful tobacco and/or nicotine products (TNP), such as reduced-risk products (RRP) (used here to refer to products that present, are likely to present, or have the potential to present, less risk of harm to people who smoke and switch to these products versus continued smoking) or modified risk tobacco products (MRTP).

Several smokeless tobacco products and a heated tobacco product were recently authorized for marketing with modified risk claims through the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) MRTP pathway [5]. The guidance on MRTP applications [6] specifies that health outcomes should be assessed during premarket evaluation and postmarket surveillance of modified risk TNPs such as these. These health outcomes comprise not only objective clinical and biological measures but also self-reported outcomes [6, 7]. Studies and reports have recently started providing evidence on the health impact of new TNPs [8]. For instance, recent papers have investigated the effects of e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products on cardiopulmonary outcomes [9,10,11,12,13,14]. However, the papers have mainly focused on clinical measurements, such as spirometry and other lung function tests; consumer perception is rarely explored or the focus of the research. Measuring self-reported experience is important for understanding the changes in the health status of individuals switching from cigarettes to RRPs and is a key component of tobacco harm reduction strategies [7]. Self-reported ratings of RRP effectiveness or adverse events might differ from clinical measures and provide another perspective as useful as the clinicians. In addition, consumer perception of positive changes in health status, functioning and other behavioral outcomes will also subsequently influence use behaviors and switching to RRPs rather than continuing smoking.

Self-perceived health status is a complex concept to define and measure, particularly within the context of TNP use [15]. While generic health status measures, such as the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), have been used to evaluate the health status of people who smoke [16, 17], comparisons have mainly been made between those who currently smoke, those who used to smoke, and those who never smoked [18, 19]. Results from these studies strongly suggest that, in healthy populations, existing generic measures are not sensitive enough to detect change over time when stopping or switching from cigarettes to other TNPs, owing to high ceiling effects [20]. While a few smoking-specific quality of life measures have been developed, these measures have not been widely implemented or standardized [15, 17, 21, 22], and the application of these smoking-specific measures to different TNP use across the risk continuum is scarce [20].

As part of the Assessment of Behavioral OUtcomes related to Tobacco and Nicotine Products (ABOUT™) Toolbox initiative [23], the present project aims at developing a new self-report measure (ABOUT™—Health and Functioning) to address the current gap and assess the impact of TNPs on health and functioning (including health status, functional status and other health-related quality of life constructs). This paper presents insights from three research activities [24, 25] from the preparatory phase of development of the measure—that is, a scoping literature review, reanalysis of consumer focus groups/interviews, and expert opinion. These three activities serve as background research to support the development of a preliminary conceptual framework of health and functioning associated with the use of TNPs.

Methods

Scoping literature review

The purpose of the review was to address two main questions among individuals who use TNPs:

-

What are the positive and negative health and functioning impacts of TNP use?

-

What concepts are evaluated by measures used to assess the positive and negative impacts of TNP use?

Given the nature and breadth of the research questions and the number of potentially relevant publications, a scoping literature review was used as it provides a means of identifying the literature and mapping the concepts and evidence on a topic by using an informative and iterative research process [26]. The scoping review involved a PubMed search (August 2018) and application of Sciome’s rapid Evidence Mapping (rEM) [27], followed by additional manual screening and review. rEM is a proprietary methodology developed by Sciome (https://www.sciome.com/) to rapidly summarize and produce a quantitative representation of the available body of scientific evidence in a particular area. The study by Lam et al. demonstrated a proof-of-concept application of the rEM methodology [27]. The PubMed search terms targeted qualitative and quantitative research among people who use TNPs (Table 1). This was supplemented by a second, parallel step of manually identifying relevant literature through other known sources. Table 2 describes the general inclusion and exclusion criteria that were applied to the scoping literature review.

After the initial rEM exercise, two reviewers (EC, SG) further manually screened the titles and abstracts of the articles identified through the automated rEM exercise against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, the selected publications underwent a full screening by two reviewers (VL and DF) for determining their relevance to the research questions for data extraction and one of the co-authors (LA-W) cross-checked the screening and resolved differences in opinion among the reviewers.

The World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [28] framework and the revised Wilson and Cleary [29, 30] model were used as a guide to broadly inform categories for data extraction from the literature on TNP use and health and functioning. These established models enable the conceptualization and description of health status and functioning (the combination of which is often referred to as health-related quality of life) [31, 32], and related outcomes and determinants. To complement and refine this and to ensure relevance to those who use TNPs, the data extracted from the literature was also grouped and labeled based on the contents of the literature reviewed.

The elements extracted from the selected papers were as follows:

-

Author, citation details, and publication type

-

Objectives and/or research questions

-

Sample type, size, and principle demographics

-

Type(s) of TNP and definitions of levels of consumption

-

Methodology, questionnaires, and statistical methods used

-

Main results

-

Results grouped in broad categories: Health Signs and Symptoms; General Health Perceptions; Quality of Life, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Functional Status; Individual Characteristics; Environmental and Social Characteristics; Biomarkers and Biological Endpoints.

Reanalysis of focus groups/in-depth interviews

The objective of the secondary analyses of existing qualitative data in people who use TNPs was to inform the drafting of the initial conceptual framework, as well as interview guides for planned concept elicitation qualitative studies to identify concepts and develop items to detect what is relevant to measure in this context. Two sets of qualitative data containing information related to health and functioning were reanalyzed and participants had consented for their data to be used in future studies. The first was from 29 focus groups (total number of participants n = 229) that were originally designed to discuss perceived risk, appeal, and intent to use TNPs [33, 34]. The focus groups—stratified by smoking status—were conducted in the United States (US; n = 12), Japan (n = 4), Italy (n = 4), and the United Kingdom (UK; n = 9) between December 2012 and August 2013. The second dataset included 40 in-depth interviews conducted in North Carolina, USA, with people who use TNPs, to discuss issues centered on perceived dependence on TNPs [35]. While 21 interviewees were people who were poly-TNPs users, 19 were people who were exclusive users of one of the following types of TNPs: cigarettes (n = 5), smokeless tobacco (n = 5), e-cigarettes (n = 5), or another type of TNP (pipes, waterpipes, or nicotine replacement therapy [NRT] products; n = 4). These interviews were conducted in August 2017. The demographics of both data sets are presented in Table 3. For reanalyzing the data, an initial codebook guided by the literature review data extraction categories was developed; however, new codes were created to complement these categories based on the thematic content analysis of the transcripts. The qualitative analysis software Quirkos [36] was used for the reanalysis.

Expert panel review

An expert panel consisting of five key opinion leaders (KOL) and five technical consultants was convened in August 28, 2018, in Neuchâtel, Switzerland. The KOLs were subject matter experts in the fields of nicotine and smoking cessation (n = 1), Patients Reported Outcomes (PRO) evaluation and scale development (n = 3), and health economics (n = 1). The consultants were experts on nicotine dependence (n = 1), psychometric validation (n = 2), market research (n = 1), and PRO development and validation (n = 1). The meeting followed an agenda and semi-structured discussion guide to facilitate conversations. First, the panel was presented with the principles underlying the tobacco harm reduction assessment strategy [4]. This session was followed by an open elicitation phase, during which two experienced moderators asked the panel to identify and discuss concepts related to health and functioning in people who use TNPs that different stakeholders might find important. Then, the panel was asked to review and respond to the concepts identified in the literature review and in the qualitative research reanalysis. These findings were discussed in depth to arrive at a consolidated preliminary conceptual framework. Each concept was presented, and the experts were asked to rank and agree on concepts to be included and how the concepts should be grouped by domains in the framework. In generating the framework, the project team and expert panel considered the themes and concepts identified under each of the categories from the scoping literature review, specific concepts from the secondary analyses of the qualitative data, and the expert panel meeting. The authors then synthesized and re-organized concepts emerging from the different preparatory phase activities under main health and functioning and conceptually-related domains. The participants also provided their input on the best strategies for planned qualitative studies to inform and support the development and validity of the proposed health and functioning measure.

Results

Scoping literature review

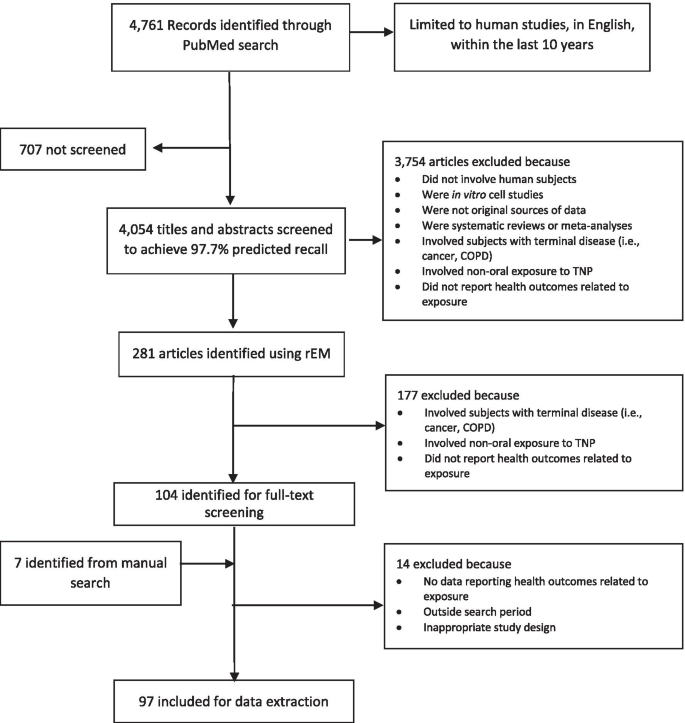

The literature search identified 4761 articles. Figure 1 (flow diagram) depicts the results of the search and screening process. Titles and abstracts were screened by the rEM exercise until the machine learning algorithms predicted 97.7% relevant references; thus, 707 abstracts were not screened. After applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria to the remaining 4,054 abstracts, 281 were identified as part of the rEM exercise. After additional manual screening and review of the abstracts and articles against the inclusion/exclusion criteria, 90 full-text articles were included for data extraction [20, 37–125]. Seven additional full-text articles were also included on the basis of a manual search [126,127,128,129,130,131,132]. Findings are summarized in Table 4 and a detailed description and data extracted from all the articles from the literature review is presented in Additional File 1.

Fifty-six publications (56/97; 58%) presented data related to health signs and symptoms. These are grouped under five core areas: mental health and cognitive functioning (28/97; 29%); pain and physical trauma (6/97; 6%); respiratory, cardiovascular and inflammatory conditions (5/97; 5%); “other” health conditions, which included insomnia, liver disease, eye health, and hearing loss (5/97; 5%); and oral health (4/97; 4%). There were also eight publications related to the effects of smoking cessation on health signs and symptoms, mostly benefits of cessation but also including perceived dependence, addiction, and withdrawal symptoms (8/97; 8%). Overall, the burden and impact of cigarette smoking on both physical and mental health symptoms was negative and generally worse among people who smoke relative to those who do not smoke. On the other hand, quitting smoking was accompanied by improvements in general physical health and psychological wellbeing. However, in spite of the positive impact of quitting smoking, loss of moments of pleasure, struggle to manage stress, the social aspects of smoking, and withdrawal symptoms were seen as barriers to quitting.

The general health perceptions of various adults who use TNPs were reported in 18 of the 97 articles (18%), with 9 of them detailing the general health perceptions related to cigarettes and 9 being related to e-cigarettes and other TNPs. Perceptions were determined by questionnaires and focus groups for evaluating the health impacts, fear of diseases, harm to others and self, social impacts (both positive [e.g., inclusion and looking “cool”] and negative [e.g., stigma and exclusion]), and other reasons for taking up or considering/attempting smoking cessation.

Quality of life, health-related quality of life, and functional status was studied in 9 of the 97 included articles (9%). These studies mostly demonstrated with generic and specific QoL, HRQoL, or functional status questionnaires that cigarette smoking was associated with a worse quality of life and that smoking cessation often resulted in an improved quality of life. However, in some cases, the use of TNPs also reportedly enabled individuals to manage their levels of anxiety and improve some aspects of social engagement and functional status.

Individual, environmental and social characteristics were found to influence the decision to smoke and/or consider or attempt to quit smoking or switching to other TNPs, as reported in 8 (8%) and 11 (11%) of 97 publications, respectively. Some key characteristics and determinants of smoking behavior included low socioeconomic status, male sex, living alone, family, and close social environment, societal stigma, and local regulations.

Finally, 12 of the 97 publications (12%) were related to studies on biomarkers and biological endpoints in people who use TNPs and showed that smoking cigarettes negatively influenced cardiovascular, respiratory, oral, renal, stress, metabolic, and inflammatory-related biomarkers and physiological assessments.

Reanalysis of focus groups/in-depth interviews

The themes from this reanalysis are summarized below and organized on the basis of the narrative of the participants of their experiences.

Perceived negative impact of smoking

Other than health, the biggest and most salient reported negative impact of smoking was the perceived lack of control related to addiction and emotional health and wellbeing. Participants reported feeling that cigarette smoking was running their lives or “holding them hostage.” They reported that this perceived lack of a sense of control or willpower often led to feelings of weakness or a feeling that they were a “slave” to cigarettes. Many respondents reported smoking even when they did not necessarily want to and experiencing feelings of obsession and craving.

Perceived lack of control and addiction were also related to the activities of the participants throughout the day. People who smoke often reported altering their activities to smoke because of patterns of behavior or routine and the experienced need for a smoke. They reported that the “need for a smoke” sensation would cause them to leave work or social events early, not attend events if smoking was not allowed, interrupt what they were doing to smoke, and get up in the middle of the night.

Fear of withdrawal symptoms, with a strong emphasis on mental/emotional health, was also prominent among reported negative impacts of smoking. This fear was often reported as limiting the willingness of individuals to try to quit smoking or facilitating a return to prior smoking behavior. Individuals reported fearing the following symptoms they associated with withdrawal: mood swings and irritability, violent or aggressive behavior, inability to concentrate, anxiety, anger, and weight gain.

Perceived benefits of smoking

Several perceived benefits were identified that keep individuals smoking or using cigarettes. These included perceptions of enhanced cognitive functioning, relaxation, a way to take a break, use as a coping strategy, a social function, a weight management tool, the perception that it feels good, and being part of one’s identity. It is also important to note that the perceived benefits of smoking often outweighed the risks and the feeling of lack of control in the participant discussions. Even people who used to smoke noted they missed the relaxation and breaks they associated with smoking.

Recognition of symptoms/diseases related to smoking

Table 5 summarizes the negative symptoms and diseases related to smoking recognized by participants in both the focus groups and interviews. These were mostly related to six main body systems (cardiovascular, digestive, oral, neurological, reproductive, and respiratory).

Impacts on physical functioning

The participants noted how smoking impacts their physical functioning. In particular, they noted how their exercise capacity during running, playing sports, walking upstairs, and general physical activity was diminished. They also reported reduced stamina and endurance, decreased physical strength, and feeling tired more easily.

Effects on emotional health

The participants also described how smoking impacts their emotional health and wellbeing. People who smoke reported feelings of shame, guilt, weakness, and a lack of control or powerlessness. They also reported feelings of depression and anxiety associated with worry about health risks. Furthermore, the participants indicated that they experienced a fear of going to places where they could not smoke, being a bad role model for their children, and (in case of people who used to smoke) going back to smoking.

Positive and negative social impacts

Smoking was perceived to have both negative and positive impacts on the social lives of participants. Smoking impacted life negatively when it was not allowed in certain environments, such as in homes, at work, and in cars and airplanes. Stigma was also associated with smoking in an environment where peers and family members do not smoke, but it was also seen as a source of group identity within social networks that had a higher prevalence of smoking behaviors. Participants reported that smoking had some positive impacts on their social interaction, because it facilitated work breaks and increased communication with peers.

Reasons people decided to try to quit

Throughout the focus groups and interviews, individuals identified several reasons why they tried to quit smoking. These included: health, diagnosis of cancer (self, family, or friend), gum disease, pregnancy, hospital stay, worry that it will “kill me,” dislike of taste or odor, social reasons, change in surroundings (fewer smoking spaces), and price.

Reasons people do not like alternatives to cigarettes

The participants’ reasons for not liking alternatives to cigarettes (i.e., less harmful TNPs/RRPs) included perceptions that the alternatives did not work (i.e., the participants still had cravings and experienced withdrawal symptoms), made them feel or get ill (nausea and vomiting), were not “the same” as cigarettes in terms of the ritual, taste, or “feeling,” or were inconvenient/too big to carry.

Expert panel review

The conclusions of the expert panel widely supported the findings of the literature review and the input from the reanalyzed focus groups and interviews. Some of the experts working in field of tobacco and nicotine provided additional insights based on their extensive experience with people who use TNPs; they highlighted the importance of the enjoyment of smoking for people who find it difficult to quit, the positive immediate benefits of quitting, and the smoking-related biomarkers that might be on a causal pathway between switching and changes in health and functioning status.

The following main areas were discussed and agreed during the meeting: (1) utility of use, referring to the perceived satisfaction and enjoyment of smoking (e.g., craving relief, weight control, and social affiliation); (2) signs and symptoms of withdrawal (e.g., anxiety, depression, and anger) and the positive immediate physical health effects of quitting smoking (e.g., better general and oral hygiene, less coughing, and improved exercise capacity); (3) functioning, including cognitive, physical, sexual, social, emotional, and role functioning; (4) worry associated with smoking and smoking-related diseases; (5) general health perceptions and quality of life; (6) association with smoking-related biomarkers that could be on the causal pathway between switching and changes in health and functioning; and (7) TNP use patterns and maintenance of switching to RRPs.

Generation of the preliminary conceptual framework

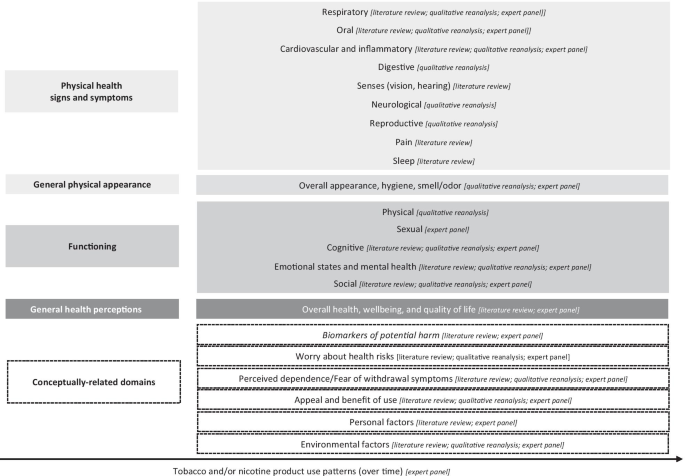

Triangulation of the findings from the literature review, qualitative input from people who use TNPs, and expert panel feedback helped generate a preliminary descriptive conceptual framework that includes the health and functioning and conceptually-related domains impacted by TNP use (Fig. 2).

Four domains related to the future health and functioning measurement model for TNP use are indicated in grey rectangular boxes and include (moving down from proximal to distal parameters) physical health symptoms (e.g., oral and respiratory symptoms), general physical condition (e.g., appearance and hygiene), functioning (physical, sexual, cognitive, emotional, and social functioning), and general health perceptions, which will be the most distal measure of health and functioning. The preparatory phase research also identified six conceptually-related domains (in dashed rectangular boxes), which are not direct indicators of health status but might influence the impact of TNP use on health and functioning. These include attitudinal variables (worry about the health risks of using TNPs and perceived dependence/fear of withdrawal symptoms associated with quitting smoking), and utilitarian ones (perceived appeal, satisfaction, and benefits of TNP use). In addition, personal factors (e.g., sociodemographic) and environmental factors (e.g., peer/family influence, policies and regulations and sociocultural context) are also reflected in the conceptual framework as indirect indicators of health and functioning.

The framework further indicates that specific behavioral indicators (i.e., TNP use patterns over time) might influence any impact of TNP use on health and functioning. Whilst other causal and reciprocal relationships and hierarchies might exist within the domains, these are not explicitly characterized in this initial draft of the framework and will have to be tested with further empirical data. Finally, identified biomarkers of potential harm (in italics and dashed box) are also integrated in this conceptual framework as part of the conceptually-related domains, because they are on a causal pathway between TNP use and changes in health and functioning [133, 134]. Biomarkers are not part of the measurement model that will be considered for a new self-report measure; however, because they are the most proximal parameters to health and functioning, they will be assessed independently as appropriate endpoints by objective clinical or biological analyses.

Discussion

Triangulation of published literature, reanalysis of qualitative data, and expert opinion helped develop the presented preliminary conceptual framework as the foundation for a new measure to assess the impact of TNPs on self-reported health and functioning. This is essential for identifying relevant concepts and understanding what is important to measure in people who use TNPs. The findings reveal the importance of not only the perceived impacts of TNP use on physical health and physical functioning, but also on aspects of mental health and social interactions and functioning, and general perceptions of health and health-related quality of life.

For the literature review, the WHO ICF [28] and Wilson and Cleary model [29, 30] served as useful guides to develop categories for data abstraction. The scoping literature review yielded 97 articles on TNP use and the relationship to health, perceptions of health, social and individual functioning, and quality of life. Overall, most studies had focused on the known negative effects of cigarette smoking (e.g., mental, respiratory, and oral health) and the rationale and motivation to quit smoking. The WHO ICF and Wilson and Clearly models were not always sufficient for identifying the breadth of relevant concepts, especially from the perspective of TNP use. Development of new codes for the reanalysis of existing qualitative data allowed for the development, extension, and exploration of the topic and provided valuable insights reported in the qualitative data reanalysis, such as the perceived benefits/satisfaction from cigarette smoking, and the rationale for quitting smoking or switching to an RRP. The findings show how this manner of secondary analysis can be valuable in health-related fields where the topic is broad and an existing body of knowledge can contribute by offering a different perspective [135].

The presentation of the preliminary conceptual framework from this preparatory phase is specific to TNP use and marks a slight departure from the established norms and characterization of the variables typically observed in existing generic health and functioning and health-related quality of life models, such as the WHO ICF and Wilson and Clearly models. Notably, specific hypothesized relationships and the hierarchy between domains are not explicitly characterized in the current draft of the framework. The framework provided an exploratory representation of the current findings to reflect a measurement instrument in people who use TNPs that would ideally be able to assess and demonstrate improvements in self-reported health and functioning status, stability of perceived positive aspects of using TNPs, and no worsening in key areas of physical and emotional health and functioning upon switching to RRPs. Nevertheless, the framework could still undergo further refinement to support the development and validation of a new measure and to further characterize and test the relationships and hierarchies between domains.

This work is not without limitations. For the scoping literature review, among the reviewed articles, not many reported on the use of e-cigarettes and other alternative tobacco or nicotine-delivery devices, because most studies had focused exclusively on cigarettes. It is possible that concepts associated with health and functioning that are relevant to other TNPs were not identified. This is most likely the consequence of the large number of publications related to cigarette use. Some concepts might also have been missed, given the large evidence base on health and functioning-related themes and concepts. However, this was also not a systematic literature search; a scoping review is generally broader than a systematic review in terms of the former having a less-defined research question, broader inclusion and exclusion criteria, and no systematic appraisal of study quality [26]. Nevertheless, the present scoping review methodology provides a lens on the overall evidence base, and regular updates on the search—specifically related to RRPs and novel TNPs and their health and functioning impacts—could be considered for fully understanding the evolving state of the art in this context. The reanalysis of existing qualitative data also has limitations related to data fit and completeness of preexisting data [136]. The insights collected from these reanalyzed studies were originally for a different purpose several years prior to the present research, and this might not completely and accurately reflect the objectives of the new project.

Considering the findings of the current research, the development of a health and functioning measure can continue to follow the FDA’s Guidance on PRO measures. As specified within the guideline, gaining input directly from the intended use populations through concept elicitation is a critical activity for ensuring content validity during the development of any new self-reported measure [137]. Continuous engagement with an expert panel can also support the refinement of the conceptual framework as well as the development of the draft and final measure.

Conclusions

The goal of this research was to identify from varied research activities key concepts and aspects of health and functioning and related changes associated with the use of TNPs. The resulting preliminary conceptual framework provides the basis for informing future research to further understand health and functioning concepts important to measure in individual who switch to RRPs and to develop a new self-report measure to assess this from the consumers’ perspective.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- ABOUT™ Toolbox:

-

Assessment of Behavioral OUtcomes related to Tobacco and Nicotine Products Toolbox

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- ICF:

-

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

- MRTP:

-

Modified risk tobacco products

- NRT:

-

Nicotine replacement therapy

- PRO:

-

Patient-Reported Outcomes

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- RRP:

-

Reduced-risk products

- rEM:

-

Rapid Evidence Mapping

- TNP:

-

Tobacco and/or nicotine products

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- US:

-

United States

- SF-36:

-

36-Item Short-Form Health Survey

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking: 50 years of progress. A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014.

Danaei G, Ding EL, Mozaffarian D, Taylor B, Rehm J, Murray CJL, et al. The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Med. 2009;6(4):e1000058.

Bilano V, Gilmour S, Moffiet T, d’Espaignet ET, Stevens GA, Commar A, et al. Global trends and projections for tobacco use, 1990–2025: an analysis of smoking indicators from the WHO Comprehensive Information Systems for Tobacco Control. Lancet. 2015;385(9972):966–76.

Zeller M, Hatsukami D. The strategic dialogue on tobacco harm reduction: a vision and blueprint for action in the US. Tob Control. 2009;18(4):324–32.

Food and Drug Administration. Modified risk orders 2020. https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/advertising-and-promotion/modified-risk-orders.

Food and Drug Administration. Modified risk tobacco product applications: draft guidance for industry 2012. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/modified-risk-tobacco-product-applications.

Institute of Medicine. Scientific standards for studies on modified risk tobacco products. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. p. 370.

Stratton K, Kwan LY, Eaton DL, editors. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2018. p. 774.

Lappas AS, Tzortzi AS, Konstantinidi EM, Teloniatis SI, Tzavara CK, Gennimata SA, et al. Short-term respiratory effects of e-cigarettes in healthy individuals and smokers with asthma. Respirology. 2018;23(3):291–7.

Meo SA, Ansary MA, Barayan FR, Almusallam AS, Almehaid AM, Alarifi NS, et al. Electronic cigarettes: impact on lung function and fractional exhaled nitric oxide among healthy adults. Am J Men’s Health. 2019;13(1):1557988318806073.

Polosa R, Cibella F, Caponnetto P, Maglia M, Prosperini U, Russo C, et al. Health impact of E-cigarettes: a prospective 3.5-year study of regular daily users who have never smoked. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):13825.

Sharman A, Zhussupov B, Sharman D, Kim I, Yerenchina E. Lung function in users of a smoke-free electronic device with HeatSticks (iQOS) versus smokers of conventional cigarettes: protocol for a longitudinal cohort observational study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2018;7(11):e10006.

Skotsimara G, Antonopoulos AS, Oikonomou E, Siasos G, Ioakeimidis N, Tsalamandris S, et al. Cardiovascular effects of electronic cigarettes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26(11):1219–28.

Wang JB, Olgin JE, Nah G, Vittinghoff E, Cataldo JK, Pletcher MJ, et al. Cigarette and e-cigarette dual use and risk of cardiopulmonary symptoms in the Health eHeart Study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(7):e0198681.

Ware JE Jr, Gandek B, Kulasekaran A, Guyer R. Evaluation of smoking-specific and generic quality of life measures in current and former smokers in Germany and the United States. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:128.

Frendl DM, Ware JE Jr. Patient-reported functional health and well-being outcomes with drug therapy: a systematic review of randomized trials using the SF-36 health survey. Med Care. 2014;52(5):439–45.

Goldenberg M, Danovitch I, IsHak WW. Quality of life and smoking. Am J Addict. 2014;23(6):540–62.

Olufade AO, Shaw JW, Foster SA, Leischow SJ, Hays RD, Coons SJ. Development of the smoking cessation quality of life questionnaire. Clin Ther. 1999;21(12):2113–30.

Sarna L, Bialous SA, Cooley ME, Jun HJ, Feskanich D. Impact of smoking and smoking cessation on health-related quality of life in women in the Nurses’ Health Study. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(10):1217–27.

Kulasekaran A, Proctor C, Papadopoulou E, Shepperd CJ, Guyer R, Gandek B, et al. Preliminary evaluation of a new german translated tobacco quality of life impact tool to discriminate between healthy current and former smokers and to explore the effect of switching smokers to a reduced toxicant prototype cigarette. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(12):1456–64.

Edelen MO. The PROMIS smoking assessment toolkit–background and introduction to supplement. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(Suppl 3):S170–4.

Shaw JW, Coons SJ, Foster SA, Leischow SJ, Hays RD. Responsiveness of the Smoking Cessation Quality of Life (SCQoL) questionnaire. Clin Ther. 2001;23(6):957–69.

Chrea C, Acquadro C, Afolalu EF, Spies E, Salzberger T, Abetz-Webb L, et al. Developing fit-for-purpose self-report instruments for assessing consumer responses to tobacco and nicotine products: the ABOUT Toolbox initiative. F1000Res. 2018;7:1878.

Food and Drug Administration. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims 2009. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/patient-reported-outcome-measures-use-medical-product-development-support-labeling-claims.

Food and Drug Administration. Patient-focused drug development: methods to identify what is important to patients guidance for industry, Food and Drug Administration Staff, and Other Stakeholders 2019. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/patient-focused-drug-development-methods-identify-what-important-patients-guidance-industry-food-and.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.

Lam J, Howard BE, Thayer K, Shah RR. Low-calorie sweeteners and health outcomes: a demonstration of rapid evidence mapping (rEM). Environ Int. 2019;123:451–8.

World Health Organisation. International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) 2001. https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/.

Ferrans CE, Zerwic JJ, Wilbur JE, Larson JL. Conceptual model of health-related quality of life. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2005;37(4):336–42.

Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273(1):59–65.

Karimi M, Brazier J. Health, health-related quality of life, and quality of life: what is the difference? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(7):645–9.

Moons P. Why call it health-related quality of life when you mean perceived health status? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;3(4):275–7.

Cano S, Chrea C, Salzberger T, Alfieri T, Emilien G, Mainy N, et al. Development and validation of a new instrument to measure perceived risks associated with the use of tobacco and nicotine-containing products. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):192.

Salzberger T, Chrea C, Cano SJ, Martin M, Atkison M, Emilien G, et al. Perceived risks associated with the use of tobacco and nicotine-containing products: findings from qualitative research. Tobacco Sci Technol. 2017;50:32–42.

Chrea C, Salzberger T, Abetz-Webb L, Afolalu EF, Cano S, Rose J, et al. PRM183—development of a fit-for-purpose tobacco and nicotine products dependence instrument. Barcelona: ISPOR Europe; 2018.

Quirkos 2.3.1 [Computer Software] 2020. https://www.quirkos.com.

Abu-Helalah MA, Alshraideh HA, Al-Serhan AA, Nesheiwat AI, Da’na M, Al-Nawafleh A. Epidemiology, attitudes and perceptions toward cigarettes and hookah smoking amongst adults in Jordan. Environ Health Prev Med. 2015;20(6):422–33.

Akturk E, Yağmur J, Açıkgöz N, Ermi N, Cansel M, Karaku Y, et al. Assessment of atrial conduction time by tissue Doppler echocardiography and P-wave dispersion in smokers. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2012;34(2):247–53.

Aubin HJ, Peiffer G, Stoebner-Delbarre A, Vicaut E, Jeanpetit Y, Solesse A, et al. The French Observational Cohort of Usual Smokers (FOCUS) cohort: French smokers perceptions and attitudes towards smoking cessation. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(100):1–8.

Becoña E, Vázquez MI, Míguez MC, Fernández del Río E, López-Durán A, Martínez Ú, et al. Smoking habit profile and health-related quality of life. Psicothema. 2013;25(4):421–6.

Bennasar Veny M, Pericas Beltrán J, González Torrente S, Segui González P, Aguiló Pons A, Tauler RP. Self-perceived factors associated with smoking cessation among primary health care nurses: a qualitative study. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2011;19(6):1437–44.

Bommelé J, Schoenmakers TM, Kleinjan M, van Straaten B, Wits E, Snelleman M, et al. Perceived pros and cons of smoking and quitting in hard-core smokers: a focus group study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:175–85.

Borland R, Yong HH, O’Connor RJ, Hyland A, Thompson ME. The reliability and predictive validity of the Heaviness of Smoking Index and its two components: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(Suppl 1):S45-50.

Bot M, Vink J, Milaneschi Y, Smit JH, Kluft C, Neuteboom J, et al. Plasma cotinine levels in cigarette smokers: impact of mental health and other correlates. Eur Addict Res. 2014;20(4):183–91.

Brody AL, Olmstead RE, Abrams AL, Costello MR, Khan A, Kozman D, et al. Effect of a history of major depressive disorder on smoking-induced dopamine release. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(9):898–901.

Brook DW, Rubenstone E, Zhang C, Brook JS. Trajectories of cigarette smoking in adulthood predict insomnia among women in late mid-life. Sleep Med. 2012;13(9):1130–7.

Brotman RM, He X, Gajer P, Fadrosh D, Sharma E, Mongodin EF, et al. Association between cigarette smoking and the vaginal microbiota: a pilot study. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:471–82.

Brown-Johnson CG, Cataldo JK, Orozco N, Lisha NE, Hickman NJ 3rd, Prochaska JJ. Validity and reliability of the Internalized Stigma of Smoking Inventory: an exploration of shame, isolation, and discrimination in smokers with mental health diagnoses. Am J Addict. 2015;24(5):410–8.

Bush T, Hsu C, Levine MD, Magnusson B, Miles L. Weight gain and smoking: perceptions and experiences of obese quitline participants. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1229.

Caldirola D, Cavedini P, Riva A, Di Chiaro NV, Perna G. Cigarette smoking has no pro-cognitive effect in subjects with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a preliminary study. Psychiatr Danub. 2016;28(1):86–90.

Caldirola D, Daccò S, Grassi M, Citterio A, Menotti R, Cavedini P, et al. Effects of cigarette smoking on neuropsychological performance in mood disorders: a comparison between smoking and nonsmoking inpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(2):e130–6.

Carpenter MJ, Gray KM. A pilot randomized study of smokeless tobacco use among smokers not interested in quitting: changes in smoking behavior and readiness to quit. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(2):136–43.

Croucher R, Haque MF, Kassim S. Oral pain before and after smokeless tobacco cessation in U.K.-resident Bangladeshi women: cross-sectional analyses. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2013;15(5):896–903.

Depp CA, Bowie CR, Mausbach BT, Wolyniec P, Thornquist MH, Luke JR, et al. Current smoking is associated with worse cognitive and adaptive functioning in serious mental illness. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;131(5):333–41.

Ditre JW, Zale EL, Heckman BW, Hendricks PS. A measure of perceived pain and tobacco smoking interrelations: pilot validation of the pain and smoking inventory. Cogn Behav Ther. 2017;46(6):339–51.

Doiron M, Dupré N, Langlois M, Provencher P, Simard M. Smoking history is associated to cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(3):322–6.

Gonzalez A, Zvolensky MJ, Vujanovic AA, Leyro TM, Marshall EC. An evaluation of anxiety sensitivity, emotional dysregulation, and negative affectivity among daily cigarette smokers: relation to smoking motives and barriers to quitting. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;43(2):138–47.

Grogan S, Fry G, Gough B, Conner M. Smoking to stay thin or giving up to save face? Young men and women talk about appearance concerns and smoking. Br J Health Psychol. 2009;14(1):175–86.

Hawari FI, Obeidat NA, Ghonimat IM, Ayub HS, Dawahreh SS. The effect of habitual waterpipe tobacco smoking on pulmonary function and exercise capacity in young healthy males: A pilot study. Respir Med. 2017;122:71–5.

Heffernan TM, O’Neill TS, Moss M. Smoking-related prospective memory deficits in a real-world task. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120(1–3):1–6.

Highland KB, McChargue DE. Stress-induced cardiovascular reactivity among African American smokers. Am J Health Behav. 2011;35(1):51–9.

Holley AL, Law EF, Tham SW, Myaing M, Noonan C, Strachan E, et al. Current smoking as a predictor of chronic musculoskeletal pain in young adult twins. J Pain. 2013;14(10):1131–9.

Ichikawa Y, Kitagawa K, Kato S, Dohi K, Hirano T, Ito M, et al. Altered coronary endothelial function in young smokers detected by magnetic resonance assessment of myocardial blood flow during the cold pressor test. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;30:73–80.

Javed F, Abduljabbar T, Vohra F, Malmstrom H, Rahman I, Romanos GE. Comparison of periodontal parameters and self-perceived oral symptoms among cigarette smokers, individuals vaping electronic cigarettes, and never-smokers. J Periodontol. 2017;88(10):1059–65.

Johnson AL, McLeish AC. Differences in panic psychopathology between smokers with and without asthma. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22(1):110–20.

Kahler CW, Daughters SB, Leventhal AM, Rogers ML, Clark MA, Colby SM, et al. Personality, psychiatric disorders, and smoking in middle-aged adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(7):833–41.

Karadoğan D, Önal Ö, Şahin D, Yazıcı S, Kanbay Y. Evaluation of school teachers’ sociodemographic characteristics and quality of life according to their cigarette smoking status: a cross-sectional study from eastern Black Sea region of Turkey. Tuberkuloz ve toraks. 2017;65(1):18–24.

Kim J, Gall SL, Dewey HM, Macdonell RA, Sturm JW, Thrift AG. Baseline smoking status and the long-term risk of death or nonfatal vascular event in people with stroke: a 10-year survival analysis. Stroke. 2012;43(12):3173–8.

Kim J, Lee S. Using focus group interviews to analyze the behavior of users of new types of tobacco products. J Prev Med Public Health. 2017;50(5):336–46.

Kralikova E, Novak J, West O, Kmetova A, Hajek P. Do e-cigarettes have the potential to compete with conventional cigarettes?: a survey of conventional cigarette smokers’ experiences with e-cigarettes. Chest. 2013;144(5):1609–14.

Lao XQ, Jiang CQ, Zhang WS, Adab P, Lam TH, Cheng KK, et al. Smoking, smoking cessation and inflammatory markers in older Chinese men: The Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203(1):304–10.

Lappan S, Thorne CB, Long D, Hendricks PS. Longitudinal and reciprocal relationships between psychological well-being and smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;22(1):18–23.

Lynch ME, Johnson KC, Kable JA, Carroll J, Coles CD. Smoking in pregnancy and parenting stress: maternal psychological symptoms and socioeconomic status as potential mediating variables. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(7):532–9.

Lyvers M, Carlopio C, Honours VB, Edwards MS. Mood, mood regulation, and frontal systems functioning in current smokers, long-term abstinent ex-smokers, and never-smokers. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2014;46(2):133–9.

Martin LM, Sayette MA. A review of the effects of nicotine on social functioning. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018;26(5):425–39.

Martinasek MP, McDermott RJ, Bryant CA. Antecedents of university students’ hookah smoking intention. Am J Health Behav. 2013;37(5):599–609.

Mattey DL, Dawson SR, Healey EL, Packham JC. Relationship between smoking and patient-reported measures of disease outcome in ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(12):2608–15.

McCann SJ. Subjective well-being, personality, demographic variables, and American state differences in smoking prevalence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(9):895–904.

McDonald EA, Ling PM. One of several “toys” for smoking: young adult experiences with electronic cigarettes in New York City. Tob Control. 2015;24(6):588–93.

McLeish AC, Zvolensky MJ, Del Ben KS, Burke RS. Anxiety sensitivity as a moderator of the association between smoking rate and panic-relevant symptoms among a community sample of middle-aged adult daily smokers. Am J Addict. 2009;18(1):93–9.

Melis M, Lobo SL, Ceneviz C, Ruparelia UN, Zawawi KH, Chandwani BP, et al. Effect of cigarette smoking on pain intensity of TMD patients: a pilot study. Cranio. 2010;28(3):187–92.

Memon A, Barber J, Rumsby E, Parker S, Mohebati L, de Visser RO, et al. What factors are important in smoking cessation and relapse in women from deprived communities? A qualitative study in Southeast England. Public Health. 2016;134:39–45.

Mendiondo MS, Alexander LA, Crawford T. Health profile differences for menthol and non-menthol smokers: findings from the National Health Interview Survey. Addiction. 2010;105(Suppl 1):124–40.

Miyatake N, Numata T, Nishii K, Sakano N, Suzue T, Hirao T, et al. Influence of cigarette smoking on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in Japanese male workers. Acta Med Okayama. 2010;64:385–90.

Mohammadi S, Mazhari MM, Mehrparvar AH, Attarchi MS. Cigarette smoking and occupational noise-induced hearing loss. Eur J Public Health. 2009;20(4):452–5.

Mohammadnezhad M, Tsourtos G, Wilson C, Ratcliffe J, Ward P. “I have never experienced any problem with my health. So far, it hasn’t been harmful”: older Greek-Australian smokers’ views on smoking: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:304–15.

Morris MC, Mielock AS, Rao U. Salivary stress biomarkers of recent nicotine use and dependence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2016;42(6):640–8.

Muir S, Marshall B. Changes in health perceptions of male prisoners following a smoking cessation program. J Correct Health Care. 2016;22(3):247–56.

Nelson JP, Pederson LL, Lewis J. Tobacco use in the Army: illuminating patterns, practices, and options for treatment. Mil Med. 2009;174(2):162–9.

Nemeth JM, Liu ST, Klein EG, Ferketich AK, Kwan MP, Wewers ME. Factors influencing smokeless tobacco use in rural Ohio Appalachia. J Community Health. 2012;37(6):1208–17.

Nikcevic AV, Spada MM. Metacognitions about smoking: a preliminary investigation. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2010;17(6):536–42.

Nunes SO, Vargas HO, Brum J, Prado E, Vargas MM, de Castro MR, et al. A comparison of inflammatory markers in depressed and nondepressed smokers. Nord J Psychiatry. 2012;14:540–6.

Oh DL, Heck JE, Dresler C, Allwright S, Haglund M, Del Mazo SS, et al. Determinants of smoking initiation among women in five European countries: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(74):1–11.

Pasco JA, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, Ng F, Henry MJ, Nicholson GC, et al. Tobacco smoking as a risk factor for major depressive disorder: population-based study. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(4):322–6.

Pina JA, Namba MD, Leyrer-Jackson JM, Cabrera-Brown G, Gipson CD. Social influences on nicotine-related behaviors. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2018;140:1–32.

Poole-Di Salvo E, Liu YH, Brenner S, Weitzman M. Adult household smoking is associated with increased child emotional and behavioral problems. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2010;31(2):107–15.

Rahman MA, Mahmood MA, Spurrier N, Rahman M, Choudhury SR, Leeder S. Why do Bangladeshi people use smokeless tobacco products? Asia-Pacific J Public Health. 2015;27(2):NP2197–209.

Rollini F, Franchi F, Cho JR, Degroat C, Bhatti M, Ferrante E, et al. Cigarette smoking and antiplatelet effects of aspirin monotherapy versus clopidogrel monotherapy in patients with atherosclerotic disease: results of a prospective pharmacodynamic study. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2014;7(1):53–63.

Romijnders K, van Osch L, de Vries H, Talhout R. Perceptions and reasons regarding e-cigarette use among users and non-users: a narrative literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(6):1190.

Rooke C, Cunningham-Burley S, Amos A. Smokers’ and ex-smokers’ understanding of electronic cigarettes: a qualitative study. Tob Control. 2016;25:e60–6.

Roth B, Bengtsson M, Ohlsson B. Diarrhoea is not the only symptom that needs to be treated in patients with microscopic colitis. Eur J Intern Med. 2013;24(6):573–8.

Sales MP, Oliveira MI, Mattos IM, Viana CM, Pereira ED. The impact of smoking cessation on patient quality of life. J Bras Pneumol. 2009;35(5):436–41.

Schane RE, Prochaska JJ, Glantz SA. Counseling nondaily smokers about secondhand smoke as a cessation message: a pilot randomized trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(2):334–42.

Schnoll RA, Goren A, Annunziata K, Suaya JA. The prevalence, predictors and associated health outcomes of high nicotine dependence using three measures among US smokers. Addiction. 2013;108(11):1989–2000.

Segarra R, Zabala A, Eguíluz JI, Ojeda N, Elizagarate E, Sánchez P, et al. Cognitive performance and smoking in first-episode psychosis: the self-medication hypothesis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;261(4):241–50.

Sherratt FC, Newson L, Marcus MW, Field JK, Robinson J. Perceptions towards electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation among Stop Smoking Service users. Br J Health Psychol. 2015;21(2):421–33.

Soneji SS, Sung HY, Primack BA, Pierce JP, Sargent JD. Quantifying population-level health benefits and harms of e-cigarette use in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3):e0193328.

Talati A, Wickramaratne PJ, Keyes KM, Hasin DS, Levin FR, Weissman MM. Smoking and psychopathology increasingly associated in recent birth cohorts. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133(2):724–32.

Tan QH. Smoking spaces as enabling spaces of wellbeing. Health Place. 2013;24:173–82.

Tatullo M, Gentile S, Paduano F, Santacroce L, Marrelli M. Crosstalk between oral and general health status in e-smokers. Medicine. 2016;95(49):e5589.

Taylor G, McNeill A, Girling A, Farley A, Lindson-Hawley N, Aveyard P. Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g1151-g.

Thompson TP, Greaves CJ, Ayres R, Aveyard P, Warren FC, Byng R, et al. An exploratory analysis of the smoking and physical activity outcomes from a pilot randomized controlled trial of an exercise assisted reduction to stop smoking intervention in disadvantaged groups. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(3):289–97.

Torigian DA, Green-McKenzie J, Liu X, Shofer FS, Werner T, Smith CE, et al. A study of the feasibility of FDG-PET/CT to systematically detect and quantify differential metabolic effects of chronic tobacco use in organs of the whole body—a prospective pilot study. Acad Radiol. 2017;24:930–40.

Ulvik A, Ebbing M, Hustad S, Midttun Ø, Nygård O, Vollset SE, et al. Long- and short-term effects of tobacco smoking on circulating concentrations of B vitamins. Clin Chem. 2010;56(5):755–63.

Vidrine JI, Businelle MS, Cinciripini P, Li Y, Marcus MT, Waters AJ, et al. Associations of mindfulness with nicotine dependence, withdrawal, and agency. Subst Abus. 2009;30(4):318–27.

Volkman JE, DeRycke EC, Driscoll MA, Becker WC, Brandt CA, Mattocks KM, et al. Smoking status and pain intensity among OEF/OIF/OND veterans. Pain Med. 2015;16(9):1690–6.

Vujanovic AA, Marshall-Berenz EC, Beckham JC, Bernstein A, Zvolensky MJ. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and cigarette deprivation in the prediction of anxious responding among trauma-exposed smokers: a laboratory test. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(11):1080–8.

Wadsworth E, Neale J, McNeill A, Hitchman SC. How and why do smokers start using e-cigarettes? Qualitative study of Vapers in London, UK. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(7):661–74.

Xie X, Dijkstra AE, Vonk JM, Oudkerk M, Vliegenthart R, Groen HJ. Chronic respiratory symptoms associated with airway wall thickening measured by thin-slice low-dose CT. Am J Roentgenol. 2014;203(4):W383–90.

Yang T, Shiffman S, Rockett IR, Cui X, Cao R. Nicotine dependence among Chinese city dwellers: a population-based cross-sectional study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(7):556–64.

Yu A, Cai X, Zhang Z, Shi H, Liu D, Zhang P, et al. Effect of nicotine dependence on opioid requirements of patients after thoracic surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2015;59(1):115–22.

Zhang X, Kahende J, Fan AZ, Barker L, Thompson TJ, Mokdad AH, et al. Smoking and visual impairment among older adults with age-related eye diseases. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8(4):A84.

Zhao L, Xu L, Lai Y, Che C, Zhou Y. Temporal changes of smoking status and motivation in Chinese patients with hepatitis B: relationship with anxiety and depression. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(15–16):2193–201.

Zorlu N, Cropley VL, Zorlu PK, Delibas DH, Adibelli ZH, Baskin EP, et al. Effects of cigarette smoking on cortical thickness in major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;84:1–8.

Miyatake N, Numata T, Nishii K, Sakano N, Suzue T, Hirao T, et al. Relation between cigarette smoking and ventilatory threshold in the Japanese. Environ Health Prev Med. 2011;16(3):185–90.

Bjørngaard JH, Gunnell D, Elvestad MB, Davey Smith G, Skorpen F, Krokan H, et al. The causal role of smoking in anxiety and depression: a Mendelian randomization analysis of the HUNT study. Psychol Med. 2012;43(4):711–9.

Chen SC, Chen HF, Peng HL, Lee LY, Chiang TY, Chiu HC. Psychometric testing of the Chinese-Version Glover-Nilsson Smoking Behavioral Questionnaire (GN-SBQ-C) for the identification of nicotine dependence in adult smokers in Taiwan. Int J Behav Med. 2017;24(2):272–9.

Doran N, Spring B, McChargue D, Pergadia M, Richmond M. Impulsivity and smoking relapse. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:641–7.

Haller CS, Etter JF, Courvoisier DS. Trajectories in cigarette dependence as a function of anxiety: a multilevel analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;139:115–20.

Jamal M, Van der Does AJW, Cuijpers P, Penninx BW. Association of smoking and nicotine dependence with severity and course of symptoms in patients with depressive or anxiety disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;126(1–2):138–46.

Krishnan-Sarin S, Reynolds B, Duhig A, Smith A, Liss T, McFetridge A, et al. Behavioral impulsivity predicts treatment outcome in a smoking cessation program for adolescent smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:79–82.

Tidey JW, Pacek LR, Koopmeiners JS, Vandrey R, Nardone N, Drobes DJ, et al. Effects of 6-week use of reduced-nicotine content cigarettes in smokers with and without elevated depressive symptoms. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(Suppl 1):59–67.

Chang CM, Cheng YC, Cho TM, Mishina EV, Del Valle-Pinero AY, van Bemmel DM, et al. Biomarkers of potential harm: summary of an FDA-sponsored public workshop. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(1):3–13.

Haziza C, de La Bourdonnaye G, Donelli A, Skiada D, Poux V, Weitkunat R, et al. Favorable changes in biomarkers of potential harm to reduce the adverse health effects of smoking in smokers switching to the menthol tobacco heating system 2.2 for three months (part 2). Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;22(4):549–59.

Bishop L, Kuula-Luumi A. Revisiting qualitative data reuse: a decade on. SAGE Open. 2017;7(1):1–15.

Sherif V. Evaluating preexisting qualitative research data for secondary analysis. In: Forum: qualitative social research, vol. 19, no. 2. 2018.

Patrick D, Burke L, Gwaltney C, Leidy N, Martin M, Molsen E, et al. Content validity—establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 1—eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health. 2011;14(8):967–77.

Acknowledgements

We thank the team at Sciome LLC for their assistance and contribution to the literature review. We thank Vivienne Law and David Floyd for their contributions to the literature review, reanalysis of qualitative data, and assistance with review of the draft manuscript. We thank Catherine Acquadro for her review of the draft manuscript. We also thank John Ware, Jed Rose, Ashley Slagle, Donald Patrick, Karl Fagerström, Stefan Cano, and Thomas Salzberger for their input and review.

Funding

Philip Morris International is the sole source of funding and sponsor of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EA, ES and CC performed conceptualization. EA, ES and LA-W performed methodology. EA, ES, SG, EC and LA-W were involved in the investigation. EA and ES were involved in writing—original draft. EA, EC, LA-W and CC were involved in writing—review & editing. EA performed visualization. ES and CC performed supervision. AB, EC and SG were involved in data curation. AB and EC were involved in project administration. LA-W performed formal analysis. CC was involved in funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Esther F. Afolalu, Emilie Clerc, and Christelle Chrea are employees of Philip Morris International. Agnes Bacso, Erica Spies, and Sophie Gallot completed the work during prior employment with Philip Morris International. Linda Abetz-Webb is a consultant for Philip Morris International.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Work completed during prior affiliation with PMI R&D: Erica Spies, Agnes Bacso, Sophie Gallot.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Summary tables of results of scoping literature review

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Afolalu, E.F., Spies, E., Bacso, A. et al. Impact of tobacco and/or nicotine products on health and functioning: a scoping review and findings from the preparatory phase of the development of a new self-report measure. Harm Reduct J 18, 79 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-021-00526-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-021-00526-z