Abstract

Background

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) is a sporadic, highly malignant tumor with a poor prognosis. The abdomen and pelvis have been reported as the primary localization sites. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are few reports on primary DSRCT in the submandibular gland.

Case presentation

We report a case of a 26-year-old Chinese man with a mass in the right submandibular gland. Imaging studies showed a hypoechoic mass in the right submandibular region. Intraoperative pathology revealed that the tumor tissue was composed of small round tumor cells and a dense desmoplastic stroma. On immunostaining, the tumor cells showed markers of epithelial, mesenchymal, myogenic, and neural differentiation. The EWSR1 gene rearrangement was detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Based on the overall morphological features and immunohistochemical findings, a final diagnosis of DSRCT was made. The patient was treated with comprehensive anti-tumor therapy mainly based on radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Conclusions

DSRCT is an uncommon malignant neoplasm with rare submandibular gland involvement. In this report, we have described a case of DSRCT in the submandibular gland and reviewed the literature on DSRCT over the past 5 years. Considering the importance of differential diagnosis between DSRCT, especially with rare extra-peritoneal involvement, and small round blue cell tumors, a full recognition of the clinicopathological features will help to better diagnose this neoplasm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) is an extremely rare and aggressive neoplasm that most commonly affects adolescents and young adults with a male predominance [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. DSRCT preferentially involves the abdominal and pelvic cavities [8,9,10,11]. DSRCT in the pleura, lung, eye, ear, and testis has been reported only in a few cases (< 5%) [3,4,5,6,7], but it is not specifically associated with any organ. Clinical symptoms are usually associated with the tumor site and lack specificity. DSRCT can metastasize in the early stage and quickly recurs, despite treatment [12,13,14,15]. Hence, its prognosis is poor. Herein, we have presented a rare case of primary DSRCT in the submandibular gland. We have described and summarized the clinicopathological and cytological features of DSRCT, in addition to discussing its diagnosis and treatment based on the literature review.

Case presentation

Clinical history

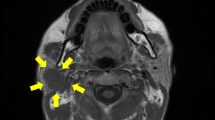

A 26-year-old Chinese man with a chief complaint of a mass in the right submandibular region for the past 1 year was admitted to Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Hunan, China. He had no significant past medical or family history. Routine physical and laboratory examinations were performed. Ultrasonography revealed a hypoechoic mass measuring approximately 28 mm × 18 mm in the right submandibular region, with an irregular shape and clear boundary (Fig. 1). Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed no other lesion. There was no evidence of metastasis to the local or distant organs. Hence, lumpectomy was performed under general anesthesia.

Pathology

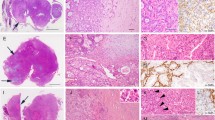

Histological examination showed sheets, cords, and nests of small round cells separated focally by desmoplastic stroma (Fig. 2a). Under higher magnification, tumor cells showed round to oval hyperchromatic nuclei with an increased nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio and inconspicuous nucleoli. The cytoplasm of the tumor cells was scanty with indistinct cytoplasmic borders (Fig. 2b). Mitotic activity and individual cell necrosis were common. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed using formalin-fixed paraffin embedded sections from representative tumor blocks and the antibodies listed in Table 1. Immunohistochemical results indicated the multi-directional differentiation of tumor cells. The immunohistochemistry results were as follows: desmin (+) (Fig. 3), FLI-1 (+), CD99 (+), E-cadherinD (+), chromogranin-A (+), neuron-specific enolase (+), vimentin (+) (Fig. 4), pan-cytokeratin (+), epithelial membrane antigen (+), CD56 (+), synaptophysin (weakly positive [+/−]), NKX2.2 (−), WT1 (−), myogenin (−), and S-100 (−). Moreover, the Ki-67 proliferation index was estimated as 50%. The tumor cells were negative for Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNA on fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). The FISH analysis with a break-apart probe proved that there was EWSR1 gene spilt in the neoplastic cells (Fig. 5). However, EWSR1-WT1 fusion detection by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction was not performed owing to certain limitations. Based on the above findings, primary lesions in the abdominal cavity and pelvic cavity were excluded, and a final diagnosis of primary DSRCT in the submandibular gland was made.

a Tumor cells were irregular sheet-like and nest-like distribution, surrounded by proliferative fibrous stroma (H&E, magnification × 200). b The tumor cells are small round or oval, with few cytoplasm, unclear cell boundaries, round or oval hyperchromatic nuclei and unclear nucleoli (H&E, magnification × 400)

Follow-up

Comprehensive anti-tumor therapy mainly based on chemotherapy and radiotherapy was first proposed. However, synchronous chemotherapy was not performed owing to the risk of bone marrow suppression. Therefore, cyclophosphamide combined with doxorubicin and vincristine chemotherapy was used for maintenance treatment. The patient is currently alive and well with no evidence of tumor recurrence.

Discussion

DSRCT, which was first described as a specific disease by Gerald and Rosai [16, 17], is a rare and aggressive soft-tissue sarcoma. Generally, DSRCT develops on the serosal surface of the abdominal cavity [8,9,10,11], but it can also be found in the lung, eye and salivary gland [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. DSRCT has no specific clinical symptoms. Most patients present with initial symptoms of abdominal pain, constipation, ascites, and vomiting [10,11,12,13,14, 27, 28]. These can be accompanied by the manifestations of cachexia, such as fatigue and emaciation. Patients may develop intestinal obstruction, hydronephrosis, and urinary tract irritation owing to tumor compression [29]. In our case, a right submandibular mass without apparent clinical manifestations was detected incidentally. DSRCT is often widely disseminated throughout the peritoneal cavity, and some patients may present with metastasis to the lymph nodes, liver, and occasionally the lungs [8, 12, 30]. Hence, its prognosis is exceedingly poor. The clinical features of previously published DSRCT cases in the last 5 years are summarized in Supplementary Table 2, Additional file 1.

Imaging examinations of DSRCT lack characteristic features. Ultrasound examination usually shows a lobulated soft tissue mass with an uneven internal echo [31]. CT usually reveals single or multiple lobular nodules or lumpy soft tissue masses, with an uneven density of the tumor body and multiple spotted calcifications [10]. The lesions tend to crowd out, surround, and invade the surrounding tissues [19]. DSRCT is usually accompanied by flakes of low intensity when there is a necrotic area in the tumor. Enhanced CT presents mild uneven enhancement and edge enhancement may be observed in some larger masses. Moreover, positron emission tomography (PET)-CT has the potential to monitor residual disease and detect relapse or tumor progression in the early stages [32]. Imaging findings are non-specific, but they can indicate the location, size, and the number of tumors, thereby contributing to biopsy, surgery, and radiotherapy.

The definitive diagnosis of DSRCT is based on typical morphological and immunohistochemical features, especially distinctive molecular characteristics. The pathological and molecular features of previously published cases of DSRCT in the last 5 years are summarized in Supplementary Table 3, Additional file 2. Histologically, the tumor consists of small round cells and peripheral desmoplastic stroma, with occasional cystic degeneration and hemorrhagic necrosis. The tumor has a variegated histology revealing rhabdoid, clear or pleomorphic cells, in addition to typical small round cell morphology. Moreover, the tumor can have intermittent areas of primitive tubules or rosette-like structures [12]. Immunohistochemically, tumor cells show a pattern of multiphenotypic differentiation [8, 15, 33, 34]. This multiple antigen expression profile is a characteristic of DSRCT and can be used to distinguish DSRCT from the other histologically related small round cell tumors. Further, para-nuclear dotted desmin positivity has important diagnostic significance. However, in our case, immunohistochemical staining showed a diffuse perinuclear staining pattern with desmin, while the characteristic dotted positivity was not prominent. Almost all cases of DSRCT are positive for WT1 with cytoplasmic and paranuclear staining pattern. Although the immunohistochemical analysis of classic cases of DSRCT tends to reveal WT1 positivity, N- and C-terminals may be useful as a form of “molecular immunohistochemistry” to identify the EWS–WT1 transcript, as the immunostaining pattern may be altered by variant transcripts and WT1 immunostaining may be negative (as in our case) [35,36,37]. To establish a DSRCT diagnosis, the interpretation of WT1 immunostaining requires information of antibody target epitopes and correlations with clinical, morphological, and molecular findings. DSRCT is distinguished by the t (11;22) (p13; q12) chromosomal translocation involving a fusion between the transcriptional activating domain of EWSR1 and the WT1 gene [38,39,40]. Studies have also suggested that the EWSR1-WT1 fusion protein can induce the expression of platelet-derived growth factor-A, which can induce the growth and proliferation of fibroblasts and the production of collagenous stroma; this may explain the characteristic reactive fibrosis of DSRCT [41]. Downstream activation of EWSR1-WT1 gene fusion includes signaling pathways of vascular endothelial growth factor, IL2RB, and insulin growth factor-1 [42,43,44]. A better understanding of the effects of these target genes will provide avenues for future treatment.

In the present case, the tumor was composed of nests of small to medium-sized cells, which might be misdiagnosed as small cell carcinoma. Small cell carcinoma can also show the immunoreactivity for epithelial and neuroendocrine markers. However, in our case, the co-expression of epithelial membrane antigen, vimentin and desmin by tumor cells strongly supports a diagnosis of DSRCT. DSRCT should also be distinguished from other carcinomas, such as malignant melanoma, malignant lymphoma, and metastatic neuroblastoma. The current case was negative for Melan-A and S100, which ruled out the likelihood of malignant melanoma. The positivity for epithelial markers helped rule out the possibility of malignant lymphoma, which often involves the lymph nodes, bone marrow and peripheral blood. In addition, stroma of massive nerve fiber network is a characteristic feature of neuroblastoma, which might be a diagnostic clue. Owing to the histological features of small round cells in the present tumor, it must be distinguished from other small round cell tumors, such as rhabdomyosarcoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET), and Ewing sarcoma (EWS). Rhabdomyosarcoma is more common in children; the tumor cells are commonly positive for myogenic markers (such as MYOD1 and myogenin), but negative for epithelial and neuroendocrine markers. Morphologically, DSRCT and PNET reveal chrysanthemum-like structure, and both of them are positive for CD99 and neuron-specific enolase. In our case, immunohistochemical results showed positivity for desmin and epithelial markers, which favors a diagnosis of DSRCT over that of PNET. EWS shares histological and immunophenotypic similarities with DSRCT. However, the survival rate of patients with DSRCT is significantly lower than that of EWS patients, which indicates that DSRCT and EWS have different biological backgrounds. EWS mainly occurs in children and is common in bones. Soft tissue involvement is rare. EWS can also be positive for cytokeratin, desmin, CD99, FLI-1, and neuroendocrine markers, which may result in confusion. The diffuse membranous positivity for CD99 is typical of EWS, but in our case, nonspecific cytoplasmic positivity for CD99 is one of the features of DSRCT. Furthermore, negative NKX2.2 is an important clue to distinguish EWS. As both EWS and DSRCT harbor EWSR1 rearrangements, the break-apart FISH assay for EWSR1 will not be helpful in the differential diagnosis. However, characteristic translocation of EWS involves EWSR1 and the ETS family of transcription factors, not WT1. Convincingly, documentation of EWSR1-WT1 fusion is the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of DSRCT [15, 27, 33]. It was not performed in our case because the sample tissue did not meet the requirements and the patient was unwilling; this is a limitation of this case. Taken together, combined with the tumor location and morphological features, as well as a distinctive pattern of multiphenotypic differentiation on immunohistochemistry, the diagnosis of DSRCT was considered. Similar to DSRCT, both myoepithelial carcinoma and synovial sarcoma are also multiphenotypic and expresse multilineage markers. Myoepithelial carcinoma expresses cytokeratin and myogenic markers, such as myogenin, smooth muscle actin and HHF35. The present case showed positivity for desmin and negativity for all other myogenic markers, P63 and CK5/6, strongly favoring a diagnosis of DSRCT. Synovial sarcoma mainly occurs in the extremities. It expresses epithelial and mesenchymal markers, but desmin positivity is uncommon, which can help in the differentiation.

Most reported cases of DSRCT are diagnosed by the histological analysis of formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissues, and so far, very few cases have been diagnosed by fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) [24, 45,46,47,48,49]. FNAC is a cheap, minimally-invasive, and well-tolerated diagnostic technique [50]. Many soft tissue tumors in any location, especially deep-seated tumors, could be sampled by FNAC [51]. Increasing evidence shows that FNAC can provide rapid and valuable diagnosis in identifying soft tissue malignancy. The cytological smear of DSRCT is characterized by stromal fragments and small, round blue cells with hyperchromatic nuclei [24, 46, 47, 49, 51,52,53]. However, sometimes no fibrosis fragments can be detected in the smear [48, 54]. Occasionally, apoptotic cells and high mitotic activity are observed [24]. Moreover, multiple ancillary techniques, such as immunohistochemical or molecular procedures, can also be performed, which enormously expand the application field of FNAC in the diagnostic approach to soft tissue tumors [24, 50]. However, accurate diagnosis depends on the comprehensive evaluation of histological characteristics, including the growth pattern of neoplastic cells and stromal characteristics; these features may not be well displayed in cytological biopsies because of the cell dispersion, loss of tissue pattern, and paucity of the specimen [52, 55]. Although FNAC can distinguish benign from malignant tumors, it is difficult to provide accurate subtypes. Indeed, some tissue types may lack characteristic morphological or molecular markers, and an accurate diagnosis can only be obtained through surgical resection and histological examination. Therefore, incisional biopsy is still considered the most accurate procedure for diagnosis. In our case, the mass was superficially located and mobile without adhesion. FNAC may not be beneficial in case of such an easily resectable tumor, as complete resection is not only a diagnostic method but also a therapeutic approach. As our patient was reluctant to undergo preoperative FNAC, we routinely performed surgical resection of the mass. We believe that FNAC may emerge as an effective diagnostic tool in the future.

Despite multimodal treatment, DSRCT is highly aggressive and has a poor prognosis. The overall survival in patients is < 3–5 years after diagnosis, and the 5-year survival rate is < 20% [12, 15, 37, 56]. There is no standardized approach for the treatment of this malignant disease. Effective cytoreduction combined with comprehensive therapies, as the best treatment strategy presented in most studies, may improve patient survival rate [14, 15, 28, 33, 34, 57]. With the in-depth analysis of molecular genetics of DSRCT, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and other methods have been gradually applied to the treatment of DSRCT in recent years [58, 59].

Conclusions

In summary, DSRCT is a poorly understood malignant tumor with characteristic morphology, immunophenotype, and cytological features. The disease does not present with specific clinical signs or symptoms. PET-CT may help diagnose recurrent disease at an early stage. The EWSR1-WT1 fusion detection by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction is the gold standard for the diagnosis of DSRCT. When it is not feasible, as in our case, definitive diagnosis mainly depends on a comprehensive analysis of histological and immunohistochemical studies. The submandibular gland is an unusual site for DSRCT, suggesting that the tumor may not have a site-specific predilection. Therefore, pathologists and clinicians have to be aware of its possible occurrence in extra-peritoneal regions. To better diagnose this rare and intriguing disease, further studies are needed in future.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this case are included within the article.

Abbreviations

- DSRCT:

-

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- FISH:

-

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- PNET:

-

Primitive neuroectodermal tumor

- EWS:

-

Ewing sarcoma

- FNAC:

-

Fine needle aspiration cytology

References

Honoré C, et al. Can we cure patients with abdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumor? Results of a retrospective multicentric study on 100 patients. Surg Oncol. 2019;29:107–12.

Gani F, et al. A national analysis of patterns of care and outcomes for adults diagnosed with desmoplastic small round cell tumors in the United States. J Surg Oncol. 2019;119(7):880–6.

Jin D, et al. Mediastinal desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(44):e22921.

Suhag S, Byrd RH, Jaiswal K. Rare case of thoracic desmoplastic small round cell tumor in a three-year-old boy. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(11):617–20.

He XR, et al. Primary desmoplastic small round cell tumor in the left orbit: a case report and literature review. Int Ophthalmol. 2019;39(2):471–5.

Xu J, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the middle ear: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(17):e0494.

Sedig L, et al. Paratesticular desmoplastic small round cell tumors: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(12):e26631.

Tian Y, Cheng X, Li Y. Chemotherapy combined with apatinib for the treatment of desmoplastic small round cell tumors: a case report. J Cancer Res Ther. 2020;16(5):1177–81.

Chen HM, Feng G. Use of anlotinib in intra-abdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumors: a case report and literature review. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:57–61.

Ofori E, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: a rare case of extraluminal bowel obstruction and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2019;50(3):560–3.

Butt SU, Bull JMH, Scott A. Desmoplastic small round-cell tumor in a young indigenous Australian man: a case report. J Glob Oncol. 2017;3(1):79–81.

Ertoy Baydar D, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the kidney: a case report. Diagn Pathol. 2020;15(1):95.

Lee SY, Koo YJ, Lee DH. Desmoplastic small round cell tumour with ovarian involvement: a case report. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;40(1):141–2.

Altal OF, et al. A 23-year-old Joradanian woman with a desmoplastic small round cell tumor involving the ovary. Am J Case Rep. 2019;20:1675–8.

Galliani CA, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the kidney: report of a case, literature review, and comprehensive discussion of the distinctive morphologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features in the differential diagnosis of small round cell tumors affecting the kidney. Adv Anat Pathol. 2020;27(6):408–21.

Gerald WL, Rosai J. Case 2. Desmoplastic small cell tumor with divergent differentiation. Pediatr Pathol. 1989;9(2):177–83.

Gerald WL, et al. Intra-abdominal desmoplastic small round-cell tumor. Report of 19 cases of a distinctive type of high-grade polyphenotypic malignancy affecting young individuals. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15(6):499–513.

Syed S, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the lung. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126(10):1226–8.

Huang A, Patel N. Orbital desmoplastic small round cell tumor in an infant. Digit J Ophthalmol. 2018;24(4):31–5.

Wang P, et al. Solid-pattern desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the orbit: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2018;11(5):2864–8.

Bengu Cobanoglu H, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor presenting as an ocular mass: unusual localization and remarkable surgical approach. Curr Oncol Rep. 2017;19(12):80.

Cai Z, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of parotid gland: a rare entity with diagnostic challenge. Int J Surg Pathol. 2020;28(7):782–6.

Ninchritz-Becerra E, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: a rare location in the parotid gland. Cureus. 2020;12(8):e10068.

Lozano MD, et al. A comprehensive diagnosis of a desmoplastic small round cell tumor of unusual location based on fine-needle aspiration cytology: report of a case arising in the parotid gland and review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2020;48(9):827–32.

Hatanaka KC, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the parotid gland-report of a rare case and a review of the literature. Diagn Pathol. 2019;14(1):43.

Rubinstein JD, et al. A case of submandibular desmoplastic small round cell tumor: diagnostic and management approaches to an atypical presentation of a rare tumor. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(4):e28178.

Vujić G, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the ovary: a case report with a new modality of treatment and review of the literature. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2020;42(5):297–302.

Atef A, et al. Primary desmoplastic small-round-cell tumor of the ovary. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2019;31(1):4.

Lee HJ, et al. Paraneoplastic secondary hypertension due to a renin-secreting desmoplastic small round cell tumor: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(5):1986–92.

Hayes-Jordan A, Anderson PM. The diagnosis and management of desmoplastic small round cell tumor: a review. Curr Opin Oncol. 2011;23(4):385–9.

Pickhardt PJ, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the abdomen: radiologic-histopathologic correlation. Radiology. 1999;210(3):633–8.

Xuesong D, Hong G, Weiguo Z. Primary desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the tibia: PET/CT and MRI presentation of a rare case and review of the literature. J Bone Oncol. 2020;20:100272.

Saleh D, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of pancreatic origin in a young child: a case report and review of literature. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e922762.

Asadbeigi SN, Zhang L, Linos K. Subcutaneous desmoplastic small round-cell tumor: an unusual primary location expanding the differential of superficial round-cell tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47(8):768–75.

Guedes-Corrêa JF, et al. Multimodal treatment of an extremely rare desmoplastic small round cell tumor primary to the brachial plexus - a case report and review of literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2019;10:140.

Faras F, et al. Primary desmoplastic small round cell tumor of upper cervical lymph nodes. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;120(1):e4–e10.

Thondam SK, et al. Intracranial desmoplastic small round cell tumor presenting as a suprasellar mass. J Neurosurg. 2015;122(4):773–7.

Mohamed M, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: evaluation of reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization as ancillary molecular diagnostic techniques. Virchows Arch. 2017;471(5):631–40.

Gedminas JM, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor is dependent on the EWS-WT1 transcription factor. Oncogenesis. 2020;9(4):41.

Sawyer JR, Tryka AF, Lewis JM. A novel reciprocal chromosome translocation t(11;22)(p13;q12) in an intraabdominal desmoplastic small round-cell tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16(4):411.

Lee SB, et al. The EWS-WT1 translocation product induces PDGFA in desmoplastic small round-cell tumour. Nat Genet. 1997;17(3):309–13.

Loktev A, Shipley JM. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT): emerging therapeutic targets and future directions for potential therapies. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2020;24(4):281–5.

Wong JC, et al. Induction of the interleukin-2/15 receptor beta-chain by the EWS-WT1 translocation product. Oncogene. 2002;21(13):2009–19.

Yamaguchi U, et al. A practical approach to the clinical diagnosis of Ewing’s sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumour and other small round cell tumours sharing EWS rearrangement using new fluorescence in situ hybridisation probes for EWSR1 on formalin fixed, paraffin wax embedded tissue. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(10):1051–6.

Setrakian S, et al. Intraabdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Report of a case diagnosed by fine needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 1992;36(3):373–6.

Insabato L, et al. Fine needle aspiration cytology of desmoplastic small round cell tumor. A case report. Acta Cytol. 1999;43(4):641–6.

Ferlicot S, et al. Intraabdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumor: report of a case with fine needle aspiration, cytologic diagnosis and molecular confirmation. Acta Cytol. 2001;45(4):617–21.

Granja NM, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumour: cytological and immunocytochemical features. Cytojournal. 2005;2(1):6.

Leça LB, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 2012;56(5):576–80.

Pagliuca F, et al. Mesenchymal neoplasms: is it time for cytology? New perspectives for the pre-operative diagnosis of soft tissue tumors in the molecular era. Pathol Res Pract. 2020;216(6):152923.

Klijanienko J, et al. Value of combined cytology and molecular information in the diagnosis of soft tissue tumors. Cancer Cytopathol. 2015;123(3):141–51.

Papke DJ Jr, Jo VY. Practical application of cytology and core biopsy in the diagnosis of mesenchymal tumors. Surg Pathol Clin. 2019;12(1):227–48.

Viswanathan S, et al. Evaluation of pediatric abdominal masses by fine-needle aspiration cytology: a clinicoradiologic approach. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38(1):15–27.

Zeppa P, et al. Occult lymph node metastasis from desmoplastic small round cell tumor diagnosed by fine needle aspiration cytology. A case report. Acta Cytol. 2003;47(3):501–5.

Hornick JL. Limited biopsies of soft tissue tumors: the contemporary role of immunohistochemistry and molecular diagnostics. Mod Pathol. 2019;32(Suppl 1):27–37.

Stiles ZE, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: a nationwide study of a rare sarcoma. J Surg Oncol. 2018;117(8):1759–67.

Zhang J, et al. Analysis of clinicopathological features and prognostic factors of desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Pathol Oncol Res. 2014;20(1):161–8.

Hendricks A, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumors: a review with focus on clinical management and therapeutic options. Cancer Treat Rev. 2021;93:102140.

Mello CA, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: a review of main molecular abnormalities and emerging therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(3):498.

Acknowledgments

We thank the professors from Department of Pathology, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Hunan, China for their assistance with pathological diagnosis.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiayu Zhou is a major contributor in writing the manuscript and compiling figures. Qingling Li, Baihua Luo and Xiaodan Fu contributed to the design and format of figures and tables. Chunlin Ou, Zhijie Xu and Xiaomei Gao helped revising the manuscript. Deyun Feng and Keda Yang confirmed the pathological analysis. Keda Yang designed and organized the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital Central South University, Hunan Province, China.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, J., Li, Q., Luo, B. et al. Primary desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the submandibular gland: a case report and literature review. Diagn Pathol 17, 6 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-021-01183-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-021-01183-3