Abstract

Purpose

To examine the dosimetric feasibility of hypofractionated/dose escalated radiation therapy in patients with localized prostate carcinoma using simultaneous integrated boost intensity-modulated proton beam therapy (SIB-IMPT) in absence or presence of prostate-rectum spacer.

Methods

IMPT technique was implemented in 23 patients with intermediate- and high-risk prostate cancer treated at West German Proton Therapy Centre from March 2016 till June 2018, using SIB technique prescribing 60 GyRBE and 72 GyRBE in 30 fractions to PTV1 (prostate and seminal vesicle) and PTV2 boost (prostate and proximal seminal vesicle), respectively. In 15 patients, a transperineal injection of hydrogel was applied prior to radiotherapy to increase the distance between prostate and rectum. Planning and all treatments were performed with a 120 ml fluid-filled endorectal balloon customised daily for each patient. For each patient, 2 lateral IMPT beams were implemented taking a field-specific range uncertainty (RU) into account. Dose volume histograms (DVH) were analyzed for PTV2, PTV2 with range uncertainty margin (PTV2RU), rectum, bladder, right/left femoral heads, and penile bulb. For late rectal toxicities, the normal tissue complication probabilities (NTCP) were calculated using different biological models. A DVH- and NTCP-based dosimetric comparison was carried out between non-spacer and spacer groups.

Results

For the 23 patients, high-quality plans could be achieved for target volume and for other organs at risk (OARs). For PTV2, the V107% was 0% and the Dmax did not exceed 106.2% of the prescribed dose. The volume PTV2RU covered by 95% of the dose ranged from 96.16 to 99.95%. The conformality index for PTV2RU was 1.12 ± 0.057 and the homogeneity index (HI) was 1.04 ± 0.014. Rectum Dmax and rectal volume receiving 73–50 Gy could be further reduced for the spacer-group. Significant reductions in mean and median rectal NTCPs (stenosis/necrosis, late rectal bleeding ≥ 2, and late rectal toxicities ≥ 3) were predicted for the spacer group in comparison to the non-spacer group.

Conclusion

Hypofractionated/dose escalated radiotherapy with SIB-IMPT is dosimetrically feasible. Further reduction of the rectal volumes receiving high and medium dose levels (73–50 Gy) and rectal NTCP could be achieved through injection of spacers between rectum and prostate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Dose-escalated external beam radiotherapy for localised prostate cancer (> 75 Gy) has in multiple trials been proven to lower the risk of biochemical relapse and increase the distant metastasis-free survival with acceptable acute and long-term toxicities [1,2,3]. Furthermore, hypofractionated radiation therapy (> 2 Gy dose/fx) has been supported in clinical studies for patients with localised prostate cancer due to the assumed low alpha/beta ratio of prostate cancer cells. Several randomised phase II/III trials revealed that hypofractionation yields similar or non-inferior cancer control outcomes, rates of late toxicity, and quality of life results as conventional fractionation [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. According to the most recently published ASTRO, ASCO, and AUA Evidence-Based Guideline, a moderate hypofractionation (2.4–3.4 Gy per fraction, daily, over 4–6 weeks) should be strongly recommended to prostate cancer patients choosing external beam radiation, across all risk groups [13]. A major consideration, or rather limitation, of hypofractionated therapy is the potential increase in the probability of normal tissue complications (NTCPs), and particularly, rectal toxicities. In this context, major attempts are being pursued to increase the therapeutic index; one of them is to offer a highly conformal radiation technique, another to increase the distance between prostate and rectal wall (anterior, lateral, or posterior) either by application of an endorectal balloon, injection of a spacer, or both.

Proton therapy as definitive therapy has been routinely used for localised prostate carcinoma in many centres [14, 15]. With pencil beam scanning (PBS), a proton beam can be magnetically scanned across the target volume, achieving distal and proximal dose conformality. The great potential of PBS is the application of a complex intensity-modulated technique (IMPT), by which the dose can be modulated along the beam axis as well as at the lateral direction of the beam, in an attempt to achieve a maximal sparing of normal tissue while delivering the prescribed dose to target volume in order to maximise the therapeutic ratio [16]. More challenging, however, is the simultaneous integrated boost technique (SIB), by which the overall treatment time can be shortened and a biologically effective dose to the smaller high-risk boost volume can be escalated by hypofractionation. At the same time, the larger low-risk target volume can receive a conventional dose of 2 Gy/fx or even lower. In case of photon therapy using intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), volumetric arc therapy (VMAT), and tomotherapy, some treatment planning studies [17,18,19,20] and phase I/II clinical trials [21,22,23] have been conducted to determine the safety and potential benefit of dose delivery using SIB fractionation. The hypofractionated/dose escalated radiation therapy with SIB technique has not yet been evaluated using proton beam therapy. The aim of this study is to demonstrate the dosimetric feasibility of SIB-IMPT technique and to analyse the dosimetric/NTCP advantages of prostate-rectum spacers in patients with prostate cancer treated with this technique.

Study design/patients and methods

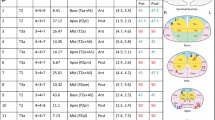

Since August 2015 a prospective single-centre register study (ProRegPros) evaluating proton therapy for patients with localised prostate cancer has been carried out at the West German Proton Therapy Centreer and since March 2016 we have begun to offer hypofractionated/dose escalated SIB-IMPT as an option to patients with intermediate- and high-risk prostate cancer. Pretreatment staging included prostate-specific antigen (PSA), histologic diagnosis, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), CT, bone scan, surgical lymphadenectomy for lymph node assessment, or radiologic assessment with MRI, and if applicable PSMA-PET/CT. SIB-IMPT with or without androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) was implemented in 23 patients with cT2b-4 histologically proven prostate adenocarcinoma treated consecutively between March 2016 and June 2018. In 15 patients, a transperineal injection of hydrogel spacer was carried out successfully one week before acquisition of the planning CT to increase distance between prostate and rectum (spacer group). Seven patients refused spacer injection, and one patient had improper implantation of the spacer (non-spacer group). Characteristics are listed in Table 1.

All patients underwent non-contrasted planning computed tomography (CT) scans with 1 mm axial slice thickness in the supine position and were immobilised with an individualised vacuum cushion and an individualised body thermoplastic cast fixed to the couch. Because of the steep drop in dose beyond the spread-out Bragg peak (SOBP) with subsequent high sensitivity of the dose distribution to the intra-fraction motion of the prostate, we aimed at minimising the prostate motion. A fixed bladder filling protocol (to drink 350 ml on empty bladder 30 min prior to treatment) applied to all patients. For further fixation of the prostate, to increase the distance between prostate and the dorsal rectal wall, and in order to gain a fixed reproducible rectal volume, the planning and treatment were implemented with a 120 ml fluid-filled endorectal balloon customised daily for each patient. For daily pretreatment prostate localisation, three fiducial markers (Visicoil™ 0.5 m × 0.5 cm) were implanted for each patient at the same setting of hydrogel spacer injection using a transperineal approach with transrectal ultrasound guidance. For better target volumes/OARs delineation, each patient underwent a planning-MRI, T1-weighted/T2-weighted images, with and without contrast media. Target volumes were defined on co-registered CT and MRI scans as follow; the gross tumor volume (GTV) was the prostate, and the clinical target volume for low risk volume (CTV1) was defined as the GTV + 5 mm peri-prostatic tissue + 2 cm of the seminal vesicles. In case of extracapsular extension or a cT4 situation, the CTV1 was laterally extended to the pelvic sidewall. The CTV for high risk volume (CTV2) was defined as the GTV + 1 cm of the seminal vesicles. Two planning volumes, PTV1 and PTV2 were generated by adding 5-mm margins in all directions (except for 7 mm expansions at the seminal vesicle region) around CTV1 and CTV2, respectively. PTV1 and PTV2 were treated simultaneously in 30 fractions with 2 dose levels; a dose of 60 Gy (2 Gy/fraction) and 72 Gy (2.4 Gy/fraction) was delivered to the PTV1, and PTV2, respectively. The dose to PTV2 is biologically equivalent to 80.2 Gy in 2 Gy/fx, assuming an α/β ratio of 1.5 for prostate cancer. The rectum was contoured as a solid organ extending from just above the anal verge up to the sigmoid flexure.

IMPT planning and optimisation were performed using the RaySearch’s treatment planning system version 5 (RaySearch Laboratories, Stockholm, Sweden) with pencil beam algorithm [24]. Two lateral-opposed IMPT beams were implemented taking into consideration the range uncertainty, by applying additional distal margin of 3.5% in the proton beam range + 2-mm to the PTV, with subsequent generation of corresponding PTV1RU and PTV2RU. Given the opposing beam arrangement, a non-robust optimization strategy was implemented based on a beam-specific PTV, considering the setup and range uncertainties. For each patient, the calculation of perturbed scenarios for the final plan showed sufficient coverage for setup- and range-uncertainty combinations.

Optimization for each plan was done until fulfilment of the dose distribution requirements and OARs constraints; Dpres(GTV,CTV) = 100%, D95%,(PTV) ≥ 95%, D2%,(PTV2) ≤ 107%; RV73Gy < 2%, RV68.4 Gy < 12%, RV66Gy < 20%, RV62Gy < 25%, RV60Gy < 35%, RV50Gy < 50%, RV40Gy < 70%, BV73Gy < 12%, BV68Gy < 20%, BV66Gy < 30%, BV64Gy < 45%, BV50Gy < 60%; femoral head Dmax < 40 Gy, penile bulb Dmean < 50 Gy.

The automatic setting of RayStation was applied for planning in this study, by which the layer separation between two adjacent energy layers equals the energy loss over the 80% level and spot spacing is 1.06 times the average projected, energy dependent sigma.

The following dosimetric parameters were analysed for PTV2 and PTV2RU; Dmax, D2%, Dmean, Dmedian, D98%, D5%, D95%, and PTV95%IDL (volume of PTV covered by 95% of the prescribed dose = 68.4 Gy).

For further plan evaluation, the conformality index (CI) and the dose homogeneity index (HI) were collected for PTV2 and PTV2RU;

-

The conformality index (CI) was defined as a ratio between reference isodose volume (VRI = volume received 95% of the prescribed dose = 68.4 Gy) and target volume = VRI/Volume of PTV

-

The HI was defined as a ratio between the dose reached in 5% of the PTV volume and the dose reached in 95% of the PTV volume = D5%/D95%

For OARs the following parameters were analysed; for rectum; Dmax, Dmean, Dmedian, RV73Gy (percent of rectal volume received 73 Gy), RV72Gy,RV70Gy, RV68.2Gy (percent of rectal volume received 95% of the prescribed dose), RV766Gy, RV65Gy, RV62G, RV60Gy, RV55Gy, RV50Gy, RV40Gy, RV30Gy, RV20Gy, and RV10Gy; For bladder; Dmax, Dmean, Dmedian, BV73Gy (percent of bladder volume received 73 Gy), BV72Gy, BV70Gy, BV68.2Gy (percent of bladder volume received 95% of the prescribed dose), BV65Gy, BV60Gy, BV55Gy, BV50Gy, BV40Gy, BV30Gy, BV20Gy and BV10Gy; for right and left femoral heads; Dmax, and Dmean; and for penile bulb; Dmean.

Further analysis was performed for the rectum as a solid organ, distinguishing between the spacer group (15 patients) and the non-spacer group (8 patients).

For the NTCP calculation, different biological models were used for the rectum; the Poisson-LQ model for necrosis/stenosis with D50 = 80 Gy, γ = 2.2, S = 1, and α/β = 3 [25]; the Layman Kutcher Burman (LKB) model for late rectal bleeding ≥ 2 with D50 = 81.8 Gy, γ = 3, m = 0.22, n = 0.29, and α/β = 3 [26]; and LKB model for late effects grade ≥ 3 with D50 = 80 Gy, m = 0.15, n = 0.06, and α/β = 3.9 [27].

The separation distance between posterior surface of the prostate and anterior rectal wall (DP-R) was measured for all patients at midline in T2-weighted planning MRI sequence at apex, mid-zone, and base and then correlated with rectal dose distribution and NTCP values.

All results were described as range and mean ± standard deviation (± SD). The Wilcoxon-Mann–Whitney-Test was used to compare continuous data between the spacer group and the non-spacer group non-parametrically. The associations between two continuous variables were quantified using Pearson correlation. Statistical analysis was done using the IBM SPSS Statistics programme V22.

Results

Plan quality

For all patients, planning with the SIB-IMPT technique resulted in good dose distribution quality (Table 1). All plans fulfilled the prescribed doses to the targets; D95%,(PTV) ≥ 95%, and D2%,(PTV) ≤ 107%). For PTV2, the V107% = 0%. The Dmax did not exceed 76.5 Gy (106.2% of the prescribed dose). The target dose coverages were generally good for all plans. The mean PTV95%IDL was 99.62% for PTV2 and 98.84% for PTV2RU. The CI for PTV2 showed a mean value of 1.27 (ranging from 1.27 to 1.63). For PTV2RU we recorded lower CI with a mean of 1.12 (range 1.02–1.21). Regarding dose homogeneity, SIB-IMPT generated homogenous dose distribution with HI mean of 1.02 for PTV2 and 1 for PTV2RU (Table2).

Regarding PTV2RU coverage, a statistically significant negative correlation was found between the volume of PTV in cc and the percentage of PTV95%IDL (R = − 0.461, R2 = 0.21 P = 0.027), which means that for smaller PTV volumes higher coverage of PTV2 could be reached. No significant correlation between the CI and corresponding volume of PTV could be observed (R = − 0.169, P = 0.441). Similarly, no significant correlation between the HI and corresponding volume of PTV could be reported (R = 0.298, P = 0.167). The linear correlation between Volume of PTV2RU in cc and PTV2RU coverage, CI, and HI are shown in Fig. 1a, b.

Organs at risk

Table 3 summarizes the DVH results for all OARs. The dose distribution satisfied all physical constraints. The mean of maximal dose delivered to the bladder was 73.5 Gy, and the BV72Gy ranged from 0.03 to 11.37%. For all patients, rectum Dmax ranged between 71.02 and 76 Gy. The RV72Gy ranged between 0 and 6.66%, the mean rectal volumes received 70 Gy, 68.4 Gy, 65 Gy, 60 Gy, 50 Gy, and 40 Gy were 4.6%, 6.02%, 8.56%, 12.14%, 19.16%, and 24.86%, respectively.

Dosimetric comparison between non-spacer group and spacer group

There was no statistically significant difference between the spacer group and the non-spacer group regarding the volume of the prostate (P = 0.333). The average of the maximum doses received by rectum was lower for spacer group in comparison to non-spacer group. Also the mean values of RV73Gy RV72Gy, RV70Gy, RV68.2Gy, RV66Gy, RV65Gy, RV62G, RV60Gy, RV55Gy, and RV50Gy were significantly reduced in spacer group compared to non-spacer group. By analysis of mean values of rectal volumes which received 40 Gy, 30 Gy, 20 Gy, and 10 Gy, we found that spacer group had lower values than non-spacer group, but these differences did not reach statistical significance (Table 4). By median comparison, the Boxplot analysis visualizes a statistical significant reduction in median of RV70Gy for spacer group vs. non-spacer group, P = 0.039. By further analysis of median values of RV60Gy, RV50G, RV40Gy, RV30Gy, and RV20Gy, we did not find any statistical significant differences between the 2 groups (Fig. 2).

For all patients, the mean DP-R at apex, mid-zone, and base were 10.67 ± SD 2.91 (range 6.6–16.4 mm), 12.93 ± SD1.97 (range 9.4–15.9 mm), and 12.07 ± SD 3.09 (range 6–16 mm), respectively. The maximal DP-R at all sections was 10.32 ± SD 5.38 (2.5–16.4 mm). The maximal DP-R correlated negatively with Rectum Dmax (R2 = 0.22, P = 0.024), Rectum Dmean (R2 = 0.21, P = 0.029), Rectum Dmedian (R2 = 0.18, P = 0.044), RV73Gy (R2 = 0.36, P = 0.002), RV72Gym (R2 = 0.316, P = 0.005), RV70Gy (R2 = 0.38, P = 0.002), RV68.4Gy (R2 = 0.39, P = 0.001), RV66Gy 4Gy (R2 = 0.38, P = 0.002), RV65Gy 4Gy (R2 = 0.39, P = 0.001), RV60Gy 4Gy (R2 = 0.345, P = 0.003), RV55Gy 4Gy (R2 = 0.31, P = 0.006), RV50Gy 4Gy (R2 = 0.27, P = 0.011), RV40Gy 4Gy (R2 = 0.23, P = 0.021), RV30Gy 4Gy (R2 = 0.192, P = 0.037). No correlation was observed between DP-R and RV20Gy or RV10Gy.

For the non-spacer group, the mean DP-R at apex, mid-zone, and base were 1.45 ± SD 0.27 (range 1.2–2 mm), 2.4 ± 1.3 (range 91.1–4.2 mm), and 2.9 ± SD 0.68 (range 2–4.1 mm), respectively. The maximal DP-R at all sections was 3.4 ± SD 0.69 mm (range 2.5–4.2 mm). For the spacer group, the mean DP-R at apex, mid-zone, and base were 10.67 ± SD 2.91 (range 6.60–16.40 mm), 12.93 ± 1.97 (range 9.40–15.90 mm), and 12.07 ± 3.09 (range 6.00–16.00 mm), respectively. The maximal DP-R at all sections was 14.01 ± SD 1.76 (10.1–16.4 mm). By analysis of each group separately, we could not observe any correlation between the maximal DP-R achieved and rectal doses except for spacer group a negative correlation between the Rectum Dmedian and the maximal DP-R (R2 = 0.28, P = 0.044) could be reported.

NTCP calculation

For all patients the SIB-IMPT plan resulted in acceptable NTCP rates of late rectal toxicities. The application of spacer provided significantly lower NTCPs. Significant decreases in mean (P = 0.005) of late rectal necrosis/Stenosis, in mean (P = 0.016) and median (P = 0.039) of late rectal bleeding, and in mean (P = 0.002) and median (P = 0.039) of late rectal toxicities ≥ 3 were predicted for spacer group vs. non-spacer group (Table 5, Fig. 3). The maximal DP-R strongly negatively correlated with NTCP values of late rectal necrosis/Stenosis (R2 = 0.347, P = 0.003), of late rectal bleeding (R2 = 0.3, P = 0.007), and of late rectal toxicities ≥ 3 (R2 = 0.32, P = 0.005).

Discussion

Moderate hypofractionation as a tool for dose escalation has gained widespread acceptance for patients with localised prostate cancer. Therefore it has become important in the West German Proton Therapy Centre to prospectively evaluate proton therapy in this context. In our feasibility study we analysed the dosimetric parameters of an optimised SIB-IMPT plan for dose escalation to 72 Gy in a hypofractionated pattern with 2.4 Gy dose/fx to the boost volume. The demonstrated results show that treatment planning with SIB-IMPT is possible and could reach the preset dose prescriptions for the PTV with good CI for all plans, while sparing the OARs. One of the drawbacks during the planning of proton therapy is the addition of RU margins to the PTV, which means that a higher volume of healthy tissue is encompassed in the radiation field. For all plans, we applied a simple beam configuration with 2 lateral opposed beams and applied the RU margins at the distal end of the beams (lateral to the prostate, and not ventral or dorsal) with avoidance of any beam direction which can stop at the rectum or at the bladder. By analysis of the PTV2RU, we reported excellent CI results with a mean of 1.12 ± 0.057 (range 1.02–1.21). Also, we could report good PTV coverage and homogeneity results.

For all patients SIB-IMPT planning could reduce the bladder and rectal volume exposed to high radiation doses. Regarding bladder dosimetry, it has been proven in multiple clinical trials that the maximum dose to the bladder and the bladder volume receiving 70 Gy are predictors for grade 2 genitourinary toxicities [28, 29]. More recently it has been proven that not only high-dose volumes can contribute to late toxicities but also mid-dose volumes (60–40 Gy) [30]. Macias et al. [31] in their study tested a 2.6 Gy/fraction to a total dose of 67.6 for low-risk (biologically equivalent to 79 Gy in 2 Gy/fx) and 70.2 Gy for intermediate–high-risk (biologically equivalent to 82 Gy in 2 Gy/fx) over 5.2–5.4 weeks, and found that BV65Gy is associated with an increased risk of genitourinary complications (P = 0.017). Beckendorf et al. published the late toxicity results of the French GETUG 06 randomised trial comparing conventional fractionation to 70 Gy and 80 Gy for localised prostate cancer. The authors found that bladder Dmax > 75 Gy (P = 0.0064) and 50% bladder volume receiving more than 44.7 Gy (P = 0.04) are associated with grade ≥ 2 late urinary toxicity [29]. In our study, the average of the bladder Dmax was 73.51 ± SD 0.70 Gy and assuming that the bladder has an α/β-level of 5 Gy, the 73.51 Gy Dmax mean in 30 fractions would be biologically equivalent to 78.2 Gy in 2 Gy/fx. Furthermore, the mean BV70Gy in our study was 7.85 ± SD 5.51% and the mean BV65Gy was 11.87 ± SD 7.38%.

The rectal dose-volume relationship with late rectal toxicity has been the scope of numerous trials. Ballare et al. [32] applied conventional fractionation with 74 Gy in 2 Gy/fx and reported that RV70Gy influenced the occurrence of late rectal grade 2 toxicity. Storey et al. [33] also tested conventional fractionation to 70 Gy or 78 Gy in 2 Gy/fx. For the 78 Gy arm, the authors found that patients with RV70Gy more than 25% had a 5-year risk of grade 2 or higher complications of 37% compared to 13% for patients with 25% or less (P = 0.05). Someya et al. [34] in their study applied 70 Gy in 35 fractions using 3-D conformal radiation therapy, or 76 Gy in 38 fractions using IMRT, and demonstrated in the multivariate analysis that patients with RV65Gy ≥ 17% had a significantly increased risk of grade 2/3 rectal bleeding (P = 0.032). Moving to the hypofractionation era, Pervez et al. used a hypofractionated dose prescription of 68 Gy in 25 fractions (2.72 Gy/fx) to the prostate and to the proximal seminal vesicle and found that RV60Gy correlated with the rectal toxicity [35]. At our centre, an endorectal balloon is regularly used for each prostate patient to daily obtain a reproducible and fixed volume of rectum and in an attempt to increase the distance between the dorsal rectal wall and the prostate. For all patients, the rectum Dmax was 73.49 ± 0.99 Gy and assuming that the rectum has an α/β-level of 5 Gy, the 73.49 Gy Dmax mean in 30 fractions would be biologically equivalent to 77.8 Gy in 2 Gy/fx. We could keep the range of RV70Gy between 0.05 and 10.72% (mean 4.64 ± SD 3.28%), and the RV65Gy ranged between 0.51 and 17.69% (8.56 ± 5.0%). In this study, we reported acceptable NTCP results with mean of 3.9% for necrosis/stenosis, 1.56% for late rectal bleeding, and 9.43% for late toxicity ≥ 3.

Strom et al. proved that hydrogel rectum spacers could move the rectum away from the prostate by an average of 12 mm, leading to a significant reduction in rectal radiation doses for patients treated with high dose rate Brachytherapy and IMRT [36]. Mariados et al. conducted a multicenter randomized controlled trial on 222 prostate cancer patients treated with IMRT to 79.2 Gy in 1.8-Gy/fx to test the dosimetric and clinical effects of spacer application. The authors found the postspacer plans had a significant reduction in mean RV70Gy compared to prespacer plans (12.4–3.3%, P < 0.0001) [37]. In the German IPI trial, 92 patients with localised prostate cancer were randomised to receive either proton therapy or carbon ion therapy to a total dose of 66 Gy in 20 fractions. Preliminary acute toxicity and quality of life results with median follow-up of 22.3 months showed that hypofractionation is feasible with 2 patients treated with protons developed grade 3 rectal fistulas. The authors reported grade 1 radiation proctitis in 12.1% and grade 2 in 5.5% of patients. In this trial, it was planned to inject hydrogel spacers for all patients, but because of rectal wall hydrogel spacer infiltration with consecutive occurrence of 2 rectal fistulas, the investigators stopped insertion of spacer gel [38]. In this study, in 15 patients we attempted to further distance the anterior rectal wall from the prostate by implantation of absorbable hydrogel rectum spacers. In concurrence to the IPI study, we did not observe any leakage of hydrogel into the rectal wall or into the rectal lumen.

The comparative analysis has proven that the hydrogel spacers could successfully reduce the rectal volumes exposed to high/medium radiation doses. As demonstrated, we found that the implantation of rectum spacers has significantly reduced the rectal Dmax by 1 Gy (P = 0.013), and also reduced the mean RV72Gy from 3.34 to 1.19%, (P = 0.005), and mean RV70Gy from 7.56 to 3.1% (P = 0.001). Further reduction in rectal volumes received 68.4 Gy, 66 Gy, 65 Gy, 62 Gy, 60 Gy, 55 Gy, and 50 Gy could be also reported. Furthermore, a negative correlation could be observed between the maximal DP-R and Rectum Dmax, Rectum Dmean, Rectum Dmedian, and rectal volumes received doses between 73 and 30 Gy.

Recently, Vanneste et al. [39] reported a statistically significant gain in NTCP, especially grade 2 late rectal bleeding and subjective sphincter control when using hydrogel rectum spacers in prostate cancer patients receiving IMRT. In this study, we reported a significant benefit of space application in reducing the mean and median of rectal NTCPs. Application of spacer reduced the mean NTCP value for late rectal toxicities from 5.87 to 2.87% for necrosis/stenosis, from 2.5 to 1.07% for late rectal bleeding ≥ 3, and from 12.75 to 7.67% for late toxicity ≥ 3. Moreover a strong negative correlation could be observed between the maximal DP-R and NTCP values of late rectal necrosis/Stenosis, late rectal bleeding, and late rectal toxicities ≥ 3.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the SIB-IMPT technique is dosimetrically feasible and resulted in high-quality proton beam plans. For healthy tissue sparing we applied two lateral opposed beams, but in the context of hypofractionated/dose escalated radiation, we still need a narrower PTV margin to reach stricter dose constraints for the bladder Dmax and the rectum Dmax. Most dose escalation trials for prostate cancer patients used a PTV margin of 5 mm in all dimensions and only 3 mm posteriorly. Our local guidelines for PTV generation by adding as 5-mm margins in all directions except of 7 mm expansions at the seminal vesicle region has been based on a retrospective study which was carried out in our centre to estimate the effect of intra‐ and interfractional organ motion on the resulting dose distribution by prostate cancer treatment using PBS [40] and based on the fact that the prostate position can be verified and corrected by using the markers, while no markers are available to correct the position of the seminal vesicle. A smaller PTV margin should be tested in the future. Application of prostate-rectum spacer is effective in sparing the rectum and leads to better NTCP results for late rectal toxicities. Currently, a clinical prospective phase II study of moderate hypofractionation (HypoPros; DRKS00011912) is under way at our center. A long follow-up will generate greater clinical evidence for SIB-IMPT technique, also taking into account the late toxicities to be matched with the NTCP models.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials can be accessed via DAK, in compliance with data protection guidelines.

Abbreviations

- SIB-IMPT:

-

Intensity-modulated proton beam therapy using simultaneous integrated boost

- PTV:

-

Planning target volume

- RU:

-

Range uncertainty

- DVH:

-

Dose volume histograms

- NTCP:

-

Normal tissue complication probabilities

- OAR:

-

Organs at risk

- CI:

-

Conformality index

- PBS:

-

Pencil beam scanning

- IMPT:

-

Intensity-modulated technique

- SIB:

-

Simultaneous integrated boost technique

- IMRT:

-

Intensity modulated radiation therapy

- VMAT:

-

Volumetric arc therapy

- PSA:

-

Prostate-specific antigen

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ADT:

-

Androgen deprivation therapy

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- SOBP:

-

Spread-out Bragg peak

- GTV:

-

Gross tumor volume

- CTV:

-

Clinical target volume

- LKB:

-

Layman Kutcher Burman

References

Kuban DA, Tucker SL, Dong L, Starkschall G, Huang EH, Cheung MR, et al. Long-term results of the M. D. Anderson randomized dose-escalation trial for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70(1):67–74.

Peeters ST, Heemsbergen WD, Koper PC, van Putten WL, Slot A, Dielwart MF, et al. Dose-response in radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: results of the Dutch multicenter randomized phase III trial comparing 68 Gy of radiotherapy with 78 Gy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(13):1990–6.

Zelefsky MJ, Pei X, Chou JF, Schechter M, Kollmeier M, Cox B, et al. Dose escalation for prostate cancer radiotherapy: predictors of long-term biochemical tumor control and distant metastases-free survival outcomes. Eur Urol. 2011;60(6):1133–9.

Dearnaley D, Syndikus I, Mossop H, Khoo V, Birtle A, Bloomfield D, et al. Conventional versus hypofractionated high-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: 5-year outcomes of the randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):1047–60.

Aluwini S, Pos F, Schimmel E, Krol S, van der Toorn PP, de Jager H, et al. Hypofractionated versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for patients with prostate cancer (HYPRO): late toxicity results from a randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(4):464–74.

Wortel RC, Oomen-de Hoop E, Heemsbergen WD, Pos FJ, Incrocci L. Moderate hypofractionation in intermediate and high risk, localized prostate cancer: Health-related quality of life from the randomized, phase 3 HYPRO trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;103:823–33.

Vargas CE, Schmidt MQ, Niska JR, Hartsell WF, Keole SR, Doh L, et al. Initial toxicity, quality-of-life outcomes, and dosimetric impact in a randomized phase 3 trial of hypofractionated versus standard fractionated proton therapy for low-risk prostate cancer. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2018;3(3):322–30.

Hoffman KE, Voong KR, Levy LB, Allen PK, Choi S, Schlembach PJ, et al. Randomized trial of hypofractionated, dose-escalated, intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) versus conventionally fractionated IMRT for localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(29):2943–9.

Karklelyte A, Valuckas KP, Griskevicius R, Janulionis E, Aleknavicius E. Acute toxicity and quality of life in high risk prostate cancer patients: updated results of randomized hypofractionation trial. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2018;23(4):284–9.

Catton CN, Lukka H, Gu CS, Martin JM, Supiot S, Chung PWM, et al. Randomized trial of a hypofractionated radiation regimen for the treatment of localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(17):1884–90.

Lee WR, Dignam JJ, Amin MB, Bruner DW, Low D, Swanson GP, et al. Randomized phase III noninferiority study comparing two radiotherapy fractionation schedules in patients with low-risk prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(20):2325–32.

Arcangeli G, Saracino B, Gomellini S, Petrongari MG, Arcangeli S, Sentinelli S, et al. A prospective phase III randomized trial of hypofractionation versus conventional fractionation in patients with high-risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78(1):11–8.

Morgan SC, Hoffman K, Loblaw DA, Buyyounouski MK, Patton C, Barocas D, et al. Hypofractionated radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer: executive summary of an ASTRO, ASCO, and AUA evidence-based guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2018;8(6):354–60.

Slater JD, Rossi CJ Jr, Yonemoto LT, Bush DA, Jabola BR, Levy RP, et al. Proton therapy for prostate cancer: the initial Loma Linda University experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59(2):348–52.

Zietman AL, Bae K, Slater JD, Shipley WU, Efstathiou JA, Coen JJ, et al. Randomized trial comparing conventional-dose with high-dose conformal radiation therapy in early-stage adenocarcinoma of the prostate: long-term results from proton radiation oncology group/american college of radiology 95-09. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1106–11.

Liu W, Li Y, Li X, Cao W, Zhang X. Influence of robust optimization in intensity-modulated proton therapy with different dose delivery techniques. Med Phys. 2012;39(6):3089–101.

Li MH, Huang SF, Chang CC, Lin JC, Tsai JT. Variations in dosimetric distribution and plan complexity with collimator angles in hypofractionated volumetric arc radiotherapy for treating prostate cancer. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2018;19(2):93–102.

Li XA, Wang JZ, Jursinic PA, Lawton CA, Wang D. Dosimetric advantages of IMRT simultaneous integrated boost for high-risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61(4):1251–7.

Onal C, Sonmez S, Erbay G, Guler OC, Arslan G. Simultaneous integrated boost to intraprostatic lesions using different energy levels of intensity-modulated radiotherapy and volumetric-arc therapy. Br J Radiol. 2014;87(1034):20130617.

Geier M, Astner ST, Duma MN, Jacob V, Nieder C, Putzhammer J, et al. Dose-escalated simultaneous integrated-boost treatment of prostate cancer patients via helical tomotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol. 2012;188(5):410–6.

Saracino B, Petrongari MG, Marzi S, Bruzzaniti V, Sara G, Arcangeli S, et al. Intensity-modulated pelvic radiation therapy and simultaneous integrated boost to the prostate area in patients with high-risk prostate cancer: a preliminary report of disease control. Cancer Med. 2014;3(5):1313–21.

Chang MG, Mukhopadhyay N, Holdford D, Skinner V, Saraiya S, Moghanaki D, et al. Phase 1/2 study of hypofractionated intensity-modulated radiation therapy for prostate cancer including simultaneously integrated boost. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2018;8(3):e149–57.

Franzese C, Fogliata A, D’Agostino GR, Di Brina L, Comito T, Navarria P, et al. Moderate hypofractionated radiotherapy with volumetric modulated arc therapy and simultaneous integrated boost for pelvic irradiation in prostate cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143(7):1301–9.

Baumer C, Geismar D, Koska B, Kramer PH, Lambert J, Lemke M, et al. Comprehensive clinical commissioning and validation of the RayStation treatment planning system for proton therapy with active scanning and passive treatment techniques. Phys Med. 2017;43:15–24.

Agren Cronqvist AK, Kallman P, Turesson I, Brahme A. Volume and heterogeneity dependence of the dose-response relationship for head and neck tumours. Acta Oncol. 1995;34(6):851–60.

Rancati T, Fiorino C, Gagliardi G, Cattaneo GM, Sanguineti G, Borca VC, et al. Fitting late rectal bleeding data using different NTCP models: results from an Italian multi-centric study (AIROPROS0101). Radiother Oncol. 2004;73(1):21–32.

Dale E, Hellebust TP, Skjonsberg A, Hogberg T, Olsen DR. Modeling normal tissue complication probability from repetitive computed tomography scans during fractionated high-dose-rate brachytherapy and external beam radiotherapy of the uterine cervix. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47(4):963–71.

Someya M, Hori M, Gocho T, Nakata K, Tsuchiya T, Kitagawa M, et al. Prediction of acute gastrointestinal and genitourinary radiation toxicity in prostate cancer patients using lymphocyte microRNA. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48(2):167–74.

Beckendorf V, Guerif S, Le Prise E, Cossett JM, Le Floch O, Chauvet B, Salem N, Chapet O, Bourdin S, Bey P. Late toxicity in the GETUG 06 randomized trial comparing 70 Gy and 80 Gy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69(3):S319.

Gulliford SL, Foo K, Morgan RC, Aird EG, Bidmead AM, Critchley H, et al. Dose-volume constraints to reduce rectal side effects from prostate radiotherapy: evidence from MRC RT01 Trial ISRCTN 47772397. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(3):747–54.

Macias V, Gonzalez Celador R, Marti-Macia C, Cigarral C, Perez-Romasanta LA. Prognostic factors for acute toxicity in prostate cancer patients treated with high-dose hypofractionated radiotherapy. Clin Transl Oncol. 2013;15(8):643–51.

Ballare A, Di Salvo M, Loi G, Ferrari G, Beldi D, Krengli M. Conformal radiotherapy of clinically localized prostate cancer: analysis of rectal and urinary toxicity and correlation with dose-volume parameters. Tumori. 2009;95(2):160–8.

Storey MR, Pollack A, Zagars G, Smith L, Antolak J, Rosen I. Complications from radiotherapy dose escalation in prostate cancer: preliminary results of a randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48(3):635–42.

Someya M, Hori M, Tateoka K, Nakata K, Takagi M, Saito M, et al. Results and DVH analysis of late rectal bleeding in patients treated with 3D-CRT or IMRT for localized prostate cancer. J Radiat Res. 2015;56(1):122–7.

Pervez N, Small C, MacKenzie M, Yee D, Parliament M, Ghosh S, et al. Acute toxicity in high-risk prostate cancer patients treated with androgen suppression and hypofractionated intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(1):57–64.

Strom TJ, Wilder RB, Fernandez DC, Mellon EA, Saini AS, Hunt DC, et al. A dosimetric study of polyethylene glycol hydrogel in 200 prostate cancer patients treated with high-dose rate brachytherapy+/−intensity modulated radiation therapy. Radiother Oncol. 2014;111(1):126–31.

Mariados N, Sylvester J, Shah D, Karsh L, Hudes R, Beyer D, et al. Hydrogel spacer prospective multicenter randomized controlled pivotal trial: dosimetric and clinical effects of perirectal spacer application in men undergoing prostate image guided intensity modulated radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;92(5):971–7.

Habl G, Uhl M, Katayama S, Kessel KA, Hatiboglu G, Hadaschik B, et al. Acute toxicity and quality of life in patients with prostate cancer treated with protons or carbon ions in a prospective randomized phase II study—the IPI trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;95(1):435–43.

Vanneste BGL, Buettner F, Pinkawa M, Lambin P, Hoffmann AL. Ano-rectal wall dose-surface maps localize the dosimetric benefit of hydrogel rectum spacers in prostate cancer radiotherapy. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2019;14:17–24.

Qamhiyeh S, Geismar D, Pottgen C, Stuschke M, Farr J. The effects of motion on the dose distribution of proton radiotherapy for prostate cancer. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2012;13(3):3639.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DAK, DG, CB, PHK and BT contributed to the design and implementation of the research. DAK, JW, DJ, CB, SSS, SP, MB, BH, TS and BT contributed to the analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This retrospective study was approved by the local ethical commission. All participants gave written informed consent.

Consent for publication

All authors gave consent for the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmad Khalil, D., Jazmati, D., Geismar, D. et al. Dosimetric feasibility of moderately hypofractionated/dose escalated radiation therapy for localised prostate cancer with intensity-modulated proton beam therapy using simultaneous integrated boost (SIB-IMPT) and impact of hydrogel prostate-rectum spacer. Radiat Oncol 17, 64 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-022-02025-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-022-02025-2