Abstract

In critical illness the regulation of inflammation and oxidative stress can improve patient outcomes, and thus omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) have been used as part of parenteral nutrition (PN) owing to their potential anti-inflammatory effects. The international lipids in PN Summit, encompassed discussions and the production of consensus guidelines concerning PN intravenous lipid emulsion (ILE) use in critical care. The Lipid Summit participants agreed that the inclusion of fish oil in ILEs is associated with meaningful clinical benefits without signals of harm, based on a strong biological rationale and current clinical evidence. Decisions concerning ILE choice should be made based on current evidence, thus addressing clinical requirements for guidance, particularly as further definitive evidence seems unlikely to occur. In addition, a future of individualized ICU care is envisioned, yielding better clinical outcomes. This approach will require the greater use of intelligent study designs incorporating the use of biomarkers of omega-3 derivatives, inflammatory-resolving processes, and/or muscle protein breakdown.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Clinical outcomes during critical illness are influenced by the balance between inflammation/oxidative stress and the anti-inflammatory immune response [1]. Normally, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory defense systems regulate inflammation and oxidative stress, but this ability can be compromised during critical illness, exacerbated by advanced age, comorbidities, and illness severity [2]. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) used in parenteral nutrition (PN) have been investigated in research and clinical practice, owing to their potential anti-inflammatory attributes [3].

The purpose of this commentary is to: (1) provide a short overview of the biological role of omega-3-PUFAs in critical illness; (2) summarize related clinical evidence; (3) discuss potential controversies in this area; and (4) outline guidance and future directions. The impetus for this commentary is derived from the international Lipids in Parenteral Nutrition Summit, held on November 3 and 4, 2022, in New Orleans, USA, involving a panel of international experts with clinical and scientific experience of PN to discuss biological and clinical aspects of lipids used in PN [4]. Consensus statements were produced to provide practical guidance regarding the use of lipid emulsions in PN that complement societal critical care nutrition guidelines [5,6,7], a full set of which will be published elsewhere [4]. Table 1 shows a subset of the consensus statements which are relevant to the critical care setting.

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: biologic aspects

Excessive and uncontrolled inflammation is a hallmark of critical illness, and the ability of the host response to resolve inflammation and return to homeostasis has implications on clinical outcomes [1]. Resolution of inflammation is now understood to be a highly coordinated and biosynthetically active programmed response in which specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs) take on important coordinating tasks [8]. Arachidonic acid and long-chain omega-3 PUFAs (i.e. eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA] and docosahexaenoic acid [DHA]) are precursors for SPMs. SPM ‘families’ include lipoxins (from arachidonic acid) and resolvins, protectins, and maresins (from long-chain omega-3 PUFAs). Each SPM family has distinct roles in inflammation resolution—actively disrupting inflammatory pathways and shifting the immune response towards resolution and homeostasis (Fig. 1) [1, 2, 8,9,10]. Contrary to many common anti-inflammatory drugs, immune modulation and tissue repair involving SPMs occurs without compromising host defences [8, 9].

The acute inflammatory response to critical illness and its resolution or progression to chronic inflammation. Pro-resolution lipid mediators (i.e. resolvins, protectins, and maresins) typically derive from omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). Pro-inflammatory lipid mediators (i.e. prostaglandins or leukotrienes) typically derive from omega-6 PUFAs. In critical illness, prolonged inflammation triggers effects on different organs that can result in organ damage. However, the timely resolution of inflammation is associated with more favorable clinical outcomes [1, 2, 8,9,10]

In addition to their inflammation-resolving effects [3], omega-3 PUFAs potentially counteract loss of muscle mass [11]. Preclinical investigations suggest that increased incorporation of EPA and DHA into membrane phospholipids leads to enhanced muscle protein synthesis and/or decreases the expression of factors regulating muscle protein breakdown [11]. The extent of these effects, however, may further depend on factors such as protein intake and age. Current clinical evidence is predominantly from oral supplementation in ageing populations and/or chronic diseases [9], rather than critically ill patients.

Lipids are an integral part of PN in all settings where PN is required, and soybean oil has traditionally been used as the intravenous lipid emulsion (ILE) of choice for PN. The 7:1 omega-6 to omega-3 PUFA ratio of soybean oil is important, since most lipid mediators derived from omega-6 PUFAs are pro-inflammatory [3]. In recent years, mixed-oil ILEs have been formulated to reduce their omega-6 PUFA content, partially replacing soybean oil with medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs), olive oil, and/or fish oil (which is rich in EPA and DHA) [3,4,5, 12].

Evidence for benefits of PN containing omega-3 PUFAs in critically ill patients

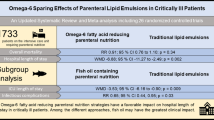

Numerous clinical studies have evaluated mixed-oil ILEs (with or without fish oil) in different critically ill patient populations, with meta-analyses providing supplementary information [7, 12,13,14]. Results of most systemic reviews/meta-analyses indicate that ILEs containing fish oil have beneficial effects on the inflammatory response and clinical outcomes [12,13,14], with a notable exception [7]. One meta-analysis screened 1054 studies, including 26 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 1733 patients, finding that PN formulations containing less omega-6 PUFAs (any mixed-oil ILE) were associated with a significant decrease in hospital length of stay (LOS), and a trend towards reduction in 28-day mortality, ICU LOS, and shorter duration of mechanical ventilation [12]. Among the different mixed-oil ILEs, PN containing fish oil reduced the duration of ICU care and the rate nosocomial infection, and a trend towards shorter hospital LOS was observed [12]. These results aligned with a previous large meta-analysis, including 24 RCTs and1421 patients, that reported fewer infections, fewer cases of sepsis, and shorter durations of both hospital and ICU LOS [13]. A subsequent network-meta-analysis by the same group compared PN with and without fish oil (any mixed-oil ILE without fish oil), confirming these findings [14]. Notz et al. also reported benefits for fish oil on mortality rates compared with placebo when fish oil was used as a stand-alone ILE [12]—though the use of pure fish-oil ILEs for adults is experimental and should not (yet) be applied outside a formal clinical study setting.

The recent international Lipid Summit (Table 1) [4], the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) [5], and the Canadian Critical Care Nutrition Organization [6], have all acknowledged the advantages of PN containing fish oil (compared with PN without fish oil) for critically ill patients. In contrast, the 2022 American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) critical care nutrition guideline update provided a weak recommendation for short-term use of either mixed-oil or pure soybean-oil ILEs in critically ill patients [7]. The meta-analyses informing this recommendation included only seven studies of mixed ICU patients [7] compared with 26 and 24 studies included in other recent meta-analyses [12, 13]. These ASPEN guidelines resulted in scientific discussions in which some co-authors of this commentary were involved [15,16,17]. For future related assessments and subsequent recommendations, we consider it important to put applied approaches and findings into a broader context by, for example, discussing results in comparison with the literature, or by formulating more specific recommendations regarding clinicians’ choice of lipid emulsion.

Challenges of data generation related to omega-3 PUFA studies in critical illness

Studies evaluating the relationship between health outcomes and lipids used in PN are often inconclusive, but this also applies for any potential link between health and nutrition [18]. There are multiple explanations for such observations. RCTs evaluating omega-3 PUFAs in critically ill patients tend to have methodological shortcomings (as do many studies involving critically ill patients), resulting in an overall lower-grade of evidence compared with other studies such as those testing therapeutic safety and efficacy [4, 18]. Comparison of complex PN formulations, variable length of PN administration, and comparatively low patient numbers can contribute to difficulties in interpreting RCT data in this field. Furthermore, critical illness is a heterogeneous state, and thus patients may respond differently to the same interventions [19]. In addition, critical care nutrition trials per se are subject to biases, which are difficult or impossible to reconcile [18]. Such effects include (beside sample heterogeneity) a suboptimal understanding of the biological mechanisms and unknown modifiers of treatment effects by nutrition. For example, the complex metabolic response to a stress situation may induce uncontrolled catabolism and the development of resistance to anabolic signals [20]. Likewise, the extensive interplay between macronutrient dose, timing, and route of administration in critical care nutrition is poorly understood [21]. In forthcoming investigations some of these challenges can be overcome by optimization of trial designs and/or the enhanced use of biomarkers to help define nutritional risk, metabolic heterogeneity, and/or when an individual may respond to a nutrition intervention [21]. Until such data are available perhaps the existing body of evidence should be considered sufficient to provide guidance for clinical care.

Guidance and future directions for the use of omega-3 PUFAs in critically ill patients: await definitive evidence, or take decisions based on available information?

The Lipid Summit participants advocate a balanced approach: providing clinicians with guidance based on preclinical and clinical evidence to help choose nutritional interventions in critically ill patients—but simultaneously acknowledging the desirability of additional, definitive evidence regarding complex subjects in clinical nutrition (Table 1, Statement 39, 100% agreement). Regarding choice of ILE for critically ill patients requiring PN, the Lipid Summit participants agreed, based on a strong biological rationale and current existing clinical evidence (as outlined above), that the inclusion of fish oil in ILEs is associated with meaningful clinical benefits without signals of harm (Table 1, statement 8; 94% agreement).

However, should we continue to work towards definitive evidence for the efficacy of ILE formulations in critically ill patients (e.g. by conducting further larger/higher-quality studies on ILEs in PN for ICU patients), or should we allocate resources towards a better understanding of patient identification, metabolic heterogeneity, and guided responses to nutrition intervention(s)? The former is a scenario that most of us consider somewhat unrealistic. We recommend the latter approach, leading towards more individualized treatment guided by biomarkers and based on multidimensional assessments. As critically ill patients are a heterogenous group, concepts have been recently proposed that promote individualizing patient care (known as a ‘treatable treat’) [19]. Translating this promising approach from theory into practice by following evidence-based medicine principles will require intelligent study designs with biomarkers at the core. Indicators of inflammatory-resolving processes and/or muscle protein breakdown will be essential, including markers derived from omega-3 PUFAs.

Conclusion

The Lipid Summit participants envision a future of individualized ICU care and are confident that designing studies rooted in precision medicine will promote such care, yielding better clinical outcomes. Furthermore, we should be able to apply our knowledge concerning ILEs containing DHA and EPA, and their SPM derivatives, to produce more informative randomized controlled trial protocols and collection of appropriate data to produce more definitive clinical recommendations.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- ASPEN:

-

American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

- DHA:

-

Docosahexaenoic acid

- ECMO:

-

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- EFA:

-

Essential fatty acid

- EFAD:

-

Essential fatty acid deficiency

- EN:

-

Enteral nutrition

- EPA:

-

Eicosapentaenoic acid

- ESPEN:

-

European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- ILE:

-

Intravenous lipid emulsion

- LOS:

-

Length of stay

- MCT:

-

Medium-chain triglyceride

- PN:

-

Parenteral nutrition

- PUFA:

-

Polyunsaturated fatty acid

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- SPMs:

-

Specialized pro-resolving mediators

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

References

Dresen E, Pimiento JM, Patel JJ, Heyland DK, Rice TW, Stoppe C. Overview of oxidative stress and the role of micronutrients in critical illness. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2023;47(Suppl 1):S38-49.

Herridge MS, Azoulay É. Outcomes after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(10):913–24.

Calder PC, Waitzberg DL, Klek S, Martindale RG. Lipids in parenteral nutrition: biological aspects. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2020;44(Suppl 1):S21–7.

Martindale RG, Calder PC, Cogle SV, Evans DC, Gramlich L, McClave SA, et al. Lipids in parenteral nutrition: translating guidelines into clinical practice. JPEN. 2024 (submitted)

Singer P, Blaser AR, Berger MM, Calder PC, Casaer M, Hiesmayr M, et al. ESPEN practical and partially revised guideline: clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin Nutr. 2023;42(9):1671–89.

Heyland DK, Lee Z-Y, Lew CCH, Ortiz LA, Patel J, Stoppe C. Composition of parenteral nutrition: type of lipids. Crit Care Nutr Syst Rev. Critical Care Nutrition.com. Accessed 13 Feb 2024.

Compher C, Bingham AL, McCall M, Patel J, Rice TW, Braunschweig C, et al. Guidelines for the provision of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2022;46(1):12–41 (Erratum in: JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2022;46(6):1458–9).

Serhan CN, Levy BD. Resolvins in inflammation: emergence of the pro-resolving superfamily of mediators. J Clin Investig. 2018;128(7):2657–69.

Serhan CN, Bäck M, Chiurchiù V, Hersberger M, Mittendorfer B, Calder PC, et al. Expert consensus report on lipid mediators: role in resolution of inflammation and muscle preservation. FASEB J. 2024;38(10):e23699.

Hill A, Nesterova E, Lomivorotov V, Efremov S, Goetzenich A, Benstoem C, et al. Current evidence about nutrition support in cardiac surgery patients—what do we know? Nutrients. 2018;10(5):597.

Blaauw R, Calder PC, Martindale RG, Berger MM. Combining proteins with n-3 PUFAs (EPA + DHA) and their inflammation pro-resolution mediators for preservation of skeletal muscle mass. Crit Care. 2024;28(1):38.

Notz Q, Lee ZY, Menger J, Elke G, Hill A, Kranke P, et al. Omega-6 sparing effects of parenteral lipid emulsions-an updated systematic review and meta-analysis on clinical outcomes in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2022;26(1):23.

Pradelli L, Klek S, Mayer K, Omar Alsaleh AJ, Rosenthal MD, Heller AR, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid-containing parenteral nutrition in ICU patients: systematic review with meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):634.

Pradelli L, Mayer K, Klek S, Rosenthal MD, Povero M, Heller AR, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids in parenteral nutrition—a systematic review with network meta-analysis on clinical outcomes. Clin Nutr. 2023;42(4):590–9.

Martindale RG, Klek S, Puthucheary Z, Rosenthal MD, Stoppe C, van Zanten ARH, et al. Commentary on “Guidelines for the provision of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.” JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2022;46(6):1223–5.

Pradelli L, Adolph M, Calder PC, Deutz NE, Carmona TG, Michael-Titus AT, et al. Commentary on “Guidelines for the provision of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.” JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2022;46(6):1226–7.

Rice TW, Bingham AL, Braunschweig C, Compher C, McCall M, Patel J, et al. Response to “Commentary on ‘Guidelines for the provision of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition’”: clarity, scientific rigor, and a call to action. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2022;46(6):1228–31.

Zeilstra D, Younes JA, Brummer RJ, Kleerebezem M. Perspective: fundamental limitations of the randomized controlled trial method in nutritional research: the example of probiotics. Adv Nutr. 2018;9(5):561–71.

Maslove DM, Tang B, Shankar-Hari M, Lawler PR, Angus DC, Baillie JK, et al. Redefining critical illness. Nat Med. 2022;28(6):1141–8.

Preiser JC, Ichai C, Orban JC, Groeneveld AB. Metabolic response to the stress of critical illness. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113(6):945–54.

Stoppe C, Wendt S, Mehta NM, Compher C, Preiser JC, Heyland DK, et al. Biomarkers in critical care nutrition. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):499.

Acknowledgements

Fresenius Kabi GmbH provided financial support for the Lipids in Parenteral Nutrition Summit and to develop this paper. Fresenius Kabi had no involvement in the study design; collection, analysis, interpretation of data; or writing of the manuscript. Dr. Martina Sintzel (mcs medical communication services, Erlenbach, Switzerland) coordinated the summit and the consensus process, and drafted this manuscript in close collaboration with Dr. Christian Stoppe and Dr. Richard Clark (freelance medical writer, Dunchurch, Warwickshire, UK), who also provided editorial and consultancy services. These services complied with international guidelines for Good Publication Practice (GPP2022).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Fresenius Kabi GmbH supported an associated advisory board meeting to discuss current evidence and future perspectives about the use and significance of Omega 3 in critically ill patients, and also provided financial support for the production of this manuscript. These services complied with international guidelines for Good Publication Practice (GPP2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors participated in the summit and conceived the research. CS and Dr. MS drafted the initial manuscript. All authors read and revised the manuscript, and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

CS has received consultancy honoraria from Abiomed, Baxter, B. Braun, and DMS, and speaker honoraria from Baxter, B. Braun, and Fresenius Kabi. RM has served as an educational consultant for Fresenius Kabi and Nestlé. SK has received speaker’s honoraria from Baxter, B. Braun, Fresenius Kabi, Nestle, Nutricia, Shire, and Vipharm and acted as an advisory board member for Fresenius Kabi, Shire, and Tracheron. PC has received consultancy honoraria from BASF, Cargill, DSM, Danone Nutricia Research, and Fresenius Kabi. PW has received investigator-initiated grant funding from the National Institutes of Health, Department of Defense, Abbott, Baxter, and Fresenius Kabi. He has served as a consultant to Abbott, Fresenius Kabi, Baxter, Mend Inc, and Nutricia, received unrestricted gift donations for nutrition research from Musclesound and DSM, and honoraria or travel expenses for CME lectures on improving nutrition care from Abbott, Baxter, Fresenius Kabi, Danone-Nutricia, DSM, and Nestlé. JP has received consulting honoraria from Fresenius Kabi and Baxter.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Stoppe, C., Martindale, R.G., Klek, S. et al. The role of lipid emulsions containing omega-3 fatty acids for medical and surgical critical care patients. Crit Care 28, 271 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-024-05053-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-024-05053-4