Abstract

Background

The spread of cervical squamous cell carcinoma to the inner surface of the uterus with replacement of the endometrium is rare. Continuity of the lesion must be demonstrated to confirm superficial spread and rule out concomitant endometrial cancer.

Case presentation

We present the case of a 66-year-old white woman with superficial spreading squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix that involved the endometrium. Her relevant past history included conization of the cervix to treat cervical intraepithelial neoplasia III with positive margins. She subsequently had three negative cervical vaginal cytology results, each with a positive high-risk human papillomavirus test. Transvaginal ultrasound showed occupation of the entire uterine cavity by dense material consistent with pyometra in addition to myometrial thinning due to tension and cervical dilation. The patient presented with greenish vaginal discharge of 3 months’ duration. The cervix was not visible during speculum examination. Access for endometrial sampling was not possible, raising suspicion of post-conization cervical stenosis. The patient was treated with laparoscopic hysterectomy with double adnexectomy. Histologic examination showed superficial squamous cell carcinoma invading the cervix to a depth of 2.8 mm; superficial spreading squamous cell carcinoma in situ was also observed in the lower uterine segment and endometrium. The patient was free of symptoms 12 months after surgery.

Conclusions

Squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix with superficial spread to the endometrium is not included in the 2020 (fifth edition) World Health Organization Classification of Female Genital Tract Tumors or the 2018 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics cervical cancer staging system. More clinical cases are needed to identify other prognostic factors and inform clinical practice guidelines on the management of this disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) accounts for approximately 80% of all cervical cancers and is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide [1]. Superficial spreading SCC is a form of cervical SCC that extends superficially to the inner surface of the uterus, replacing the endometrium. There are insufficient data to compare superficial spreading SCC of the cervix with other types of cervical cancer. More clinical cases are needed to identify additional prognostic factors and inform clinical practice guidelines on the management of this disease.

Case presentation

The patient was a 66-year-old white woman who had had six pregnancies (four live births via Cesarean delivery and two miscarriages) and reached menopause at age 51 years. She did not smoke tobacco or drink alcohol. She had a history of hypertension and dyslipidemia and is currently taking enalapril and atorvastatin. She has no remarkable family history. In her country of origin, she had undergone conization of the cervix to treat cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) III with positive margins in 2011. She did not attend any follow-up appointments. In 2014, she presented for clinical evaluation and had a normal cytology result, but tested positive for high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV); colposcopic examination showed no apparent lesions. The patient visited our clinic for the first time in 2015 and underwent cervical and vaginal cytology. She was asymptomatic at the time. The sample was satisfactory for analysis and tested negative for atypical cells and positive for HR-HPV 16. Co-testing was scheduled for a year later, but the patient did not attend the appointment and was lost to follow-up. She returned in 2020, presenting with greenish vaginal discharge of 3 months’ duration. The cervix was not visible during speculum examination; a point-like orifice consistent with the cervical canal was observed towards the right of the vaginal fornix. It was not possible to gain access for endometrial sampling, and post-conization cervical stenosis was suspected. Transvaginal ultrasound showed occupation of the entire uterine cavity by dense material consistent with pyometra, in addition to myometrial thinning due to tension and cervical dilation. Cervical and vaginal cytology was negative for atypical cells and positive for HPV 16. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis (Fig. 1A) confirmed the presence of pyometra (139 mm × 70 mm × 61 mm). The staging study was negative. The patient was treated with laparoscopic hysterectomy with double adnexectomy. Examination of the abdominal cavity showed no abnormal findings. The physical and neurological examination on admission was normal. Upon arrival, her vital signs were blood pressure 130/80 mmHg, pulse rate 80 beats per minute, respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute, and body temperature 36.8 °C. The results of routine blood tests showed a normal blood cell count; hemoglobin (Hgb) 12.1 g/dl, leukocytes (10 × 103/μl), neutrophils: 7 × 109/L, platelets 250 × 109/L, negative C-reactive protein (CRP; < 0.5 mg/L). Screening for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serologies were done and found to be negative. Furthermore, liver enzymes, coagulogram, urea and creatinine, and acid–base status of the blood were normal. During admission, intravenous analgesia was prescribed with 1 g of paracetamol every 8 hours. The patient was discharged on clinical day 1 and hemodynamically stable. Oral antiinflammatories were prescribed as needed, and she did not require readmission. Follow-up visits were every 4 months. The patient was symptom free 12 months after surgery.

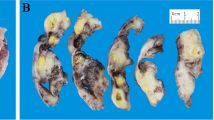

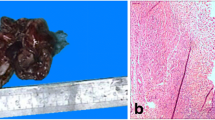

A Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan. Marked distension of the uterine cavity (yellow arrow) and cervical canal (red arrow). Presence of dense material consistent with pyometra. B Squamous cell carcinoma with superficial invasion (2.8 mm). Staining for p16 ×250. C Note the large number of endometrial glands in the tumor. Hematoxylin–eosin ×100

Histologic examination showed superficial SCC invading the cervix to a depth of 2.8 mm and occupying all quadrants; p16 staining was positive. The diagnosis was HPV-associated SCC. Superficial spreading SCC in situ was also observed in the lower uterine segment and endometrium (Fig. 1B, C). There were no signs of lymphovascular invasion or infiltration of the fallopian tubes or ovaries. SCC of the cervix with superficial spread to the endometrium is rare. It is not included in the 2020 (fifth edition) World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Female Genital Tract Tumors or the 2018 FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) cervical cancer staging system. Nonetheless, we consider that the patient had stage IA1 (FIGO 2018) pT1a1 (American Joint Committee on Cancer 2018) disease, and as such the treatment was sufficient.

Discussion and conclusions

We present the case of a woman with superficial spreading SCC of the cervix that involved the endometrium. We include ultrasound and microscopy images to perfectly illustrate the clinical case. We review the literature based on 54 cases retrieved by a keyword search in PubMed and Medline in Table 1. This review is the largest to date on this topic. Superficial spreading SCC of the cervix occurs mainly in menopausal women with history of cervical conization. The most common clinical presentation is vaginal bleeding and pyometra.

Carcinoma in situ (preinvasive or CIN III) or invasive carcinoma that is strictly confined to the cervix or extends into the uterine corpus (stage I, FIGO 2018) is by definition a histologic diagnosis. Nevertheless, cervical SCC with superficial spread to the endometrium or upper genital tract is not recognized in the latest FIGO or WHO classification systems. The main site affected by superficially spreading cervical SCC in the cases reported to date has been the endometrium, generally in isolation and without signs of invasive growth (carcinoma in situ). There have, however, been a few reports of unilateral or bilateral involvement of the fallopian tubes and/or ovaries in addition to endometrial extension. There has just been one report of distant metastasis, involving the greater omentum [2].

A genetic study of five patients with superficial spreading cervical SCC showed a single clonal process and frequent loss of heterozygosity at 6p, 6q, 11p, and 11q [3], all loci that are typically lost in cervical SCC. Consistent with our case, superficial spreading cervical SCC stains positively for p16, a surrogate immunohistochemical marker of HPV. HR-HPV infection is known to have a key pathogenic role in cervical SCC [4]. In one of the studies reviewed, all the samples analyzed were HPV 16 positive [4], suggesting that persistent HR-HPV infection is a key factor in the development of superficial spreading cervical SCC. In another study, CD138 was strongly expressed in superficial carcinoma cells in both the cervix and endometrium [5], suggesting that it may also be involved through the regulation of cell–cell interactions.

Conization followed by regular cytology and HPV detection (co-testing) is the standard procedure for CIN III management and follow-up. Cervical stenosis is a late complication of conization [6] and can result in unsatisfactory cytological and colposcopy follow-up and consequently higher false-negative rates and fewer early detections of recurrence [2]. Apart from cervical and vaginal cytology, patients with post-conization cervical stenosis should undergo additional procedures such as endocervical cytology, endometrial biopsy, and/or transvaginal pelvic ultrasound, especially if they have persistent HR-HPV infection.

As superficial spreading SCC of the cervix is so rare, there is limited information on its prognosis or clinical management [7,8,9]. It is more common in postmenopausal women, and the main presenting signs are vaginal bleeding and discharge (Table 1). HPV genotyping in combination with cervical and vaginal cytology is useful. An important role for local immune intolerance has been postulated. HPV vaccination is probably the only primary prevention measure possible. There have been reports that superficially spreading cervical SCC with endometrial involvement has worse prognosis than standard endometrial SCC [10,11,12,13]. Tumor volume and lymphovascular invasion are known risk factors for recurrence in cervical cancer and are also predictive of lymph node metastasis. Cervical stenosis with pyometra [14] and previous radiotherapy [15] can favor superficial spread. It is currently difficult to draw any conclusions regarding optimal treatment. Based on FIGO 2018 recommendations, a simple hysterectomy would be sufficient for SCC in situ or stage IA1 SCC without nodal involvement and an isolated focus of carcinoma in situ in the endometrium.

SCC of cervix is the most common tumor of the female genital tract, accounting for approximately 80% of all cervical cancers. Carcinoma of the cervix generally spreads upwards to the parametrium and through lymphatic invasion to the uterine wall. Although superficial spreading SCC of the cervix is rare, it should be considered in postmenopausal women with past history of cervical conization and persistent HR-HPV infection, as early diagnosis is important. There are insufficient data to compare superficial spreading SCC of the cervix with other types of cervical cancer. More clinical cases are needed to identify additional prognostic factors and inform clinical practice guidelines on the management of this disease.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CIN:

-

Carcinoma in situ

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- FIGO:

-

International federation of gynecology and obstetrics

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HR-HPV:

-

Human high-risk papillomavirus

- SCC:

-

Squamous cell carcinoma

- WHO:

-

World health organization

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7–34.

Nakajima T, Hatta H, Nishida T, Minamisaka T, Miwa S, Terahata S, Imura J. Superficial spread of cervical squamous cell carcinoma to the upper genital tract and dissemination to the omentum. Pathol Int. 2019;69(2):119–21.

Kushima M, Fujii H, Murakami K, et al. Simultaneous squamous cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix and upper genital tract: Loss of heterozygosity analysis demonstrates clonal neoplasms of cervical origin. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2001;20:353–8.

Chao A, Wang AM, Wang TH, Wu TI, Chao AS. An atypical and fatal case of pyometra accompanied by the superficial spread of squamous cell carcinoma of the endometrium and the fallopian tubes. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;52(3):440–2.

Ishida M, Okabe H. Superficial spreading squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix involving the endometrium: report of two cases with emphasis on the likely molecular mechanism. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:31–4.

Tanaka Y, Ueda Y, Kakuda M, Kubota S, Matsuzaki S, Iwamiya T, Okazawa A, Matsuzaki S, Hashimoto K, Kobayashi E, Mabuchi S, Sawada K, Tomimatsu T, Yoshino K, Kimura T. Predictors for recurrent/persistent high-grade intraepithelial lesions and cervical stenosis after therapeutic conization: a retrospective analysis of 522 cases. Int J Clin Oncol. 2017;22(5):921–6.

Gungor T, Altinkaya SO, Ozat M, Akbay S, Mollamahmutoglu L. Unusual form of superficial spreading squamous cell carcinoma of cervix involving the endometrium, bilateral tubes and ovaries: a case report with literature review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283:323–7.

Tan GC, Isa MR, Ng SP, Jamil YM. Unusual form of superficial spreading microinvasive squamous cell carcinoma of uterine cervix involving the endometrium of uterus. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004;30:363–7.

Muthusamy RK, Mehta SS. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the cervix with superficial intraepithelial extension to the endometrium of lower uterine segment: a rare presentation. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2017;38:88–9.

Kanbour AI, Stock RJ. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the endometrium and fallopian tube as superficial extension of invasive cervical carcinoma. Cancer. 1978;42:570e80.

Zidi YS, Bouraoui S, Atallah K, Kchir N, Haouet S. Primary in situ squamous cell carcinoma of the endometrium, with extensive squamous metaplasia and dysplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;88:444e6.

Goodman A, Zukerberg LR, Rice LW, Fuller AF, Young RH, Scully RE. Squamous cell carcinoma of the endometrium: a report of eight cases and a review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;61:54e60.

Takeuchi K, Tsujino T, Yabuta M, Kitazawa S. A case of primary squamous cell carcinoma of the endometrium associated with extensive “ichthyosis uteri.” Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2012;33:522e4.

Marwah N, Garg M, Singh S, Sethi D, Sen R. Unusual form of squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix extending in situ into the endometrium: three case reports and review of literature. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2012;2:139–41.

Gupta S, Gupta IM, Tiwari PV. In-situ carcinoma of the uterine cérvix showing superficial endometrial spread. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1979;58:507–8.

Langley F. Squamous cell carcinoma of multicentric origin, involving cervix, uterus and Fallopian tubes. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1954;61(6):821–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.1954.tb07734.x.

Friedell Gh. Endometrial surface involvement by carcinoma of the uterine cervix; report of two cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1958;12(2):179–84.

Brocheriou C. Apropos of a case of “uterine ichthyosis”: intraepithelial propagation of an “invasive” carcinoma of cervico-isthmic origin. Arch Anat Pathol (Paris). 1963;11:259–61.

Kairys LR. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the endometrial cavity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1964;88:548–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(64)90516-2.

Delattre A. Cancerous stenosis of the uterine isthmus with pyometra and “uterine ichthyosis.” J Sci Med Lille. 1965;83(11):625–30 (French).

Salm R. Superficial intrauterine spread of intraepithelial cervical carcinoma. J Pathol. 1969;97(4):719–23.

Weill S. Intra-epithelial pavement cell epithelioma extending through the whole surface of the uterine cavity and the surface of one of the fallopian tubes. Report of a case. Rev Fr Gynecol Obstet. 1968;63(4):211–4 (French).

Hallgrímsson JT. Carcinoma in situ of the endocervix, corpus uteri and both oviducts. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1967;46(2):268–72.

Ferenczy A, Richart RM, Okagaki T. Endometrial involvement by cervical carcinoma in situ. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110(4):590–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(71)90706-x.

Quizilbash AH, DePetrillo AD. Endometrial and tubal involvement by squamous carcinoma of the cervix. Am J Clin Pathol. 1975;64(5):668–71.

Kamalian N, Ghafoorzadeh D. Squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix, with extension in an in situ fashion into the endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1977;15(3):267–9.

Schmitt K. Intraepithelial spread of the squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix into the endometrium. A contribution to the question of a surface spread of the cervical carcinoma. Z Krebsforsch Klin Onkol Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1977;89(1):45–51.

Punnonen R, Gronroos M, Vaajalahti P. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ from the uterine cervix to the distal end of the fallopian tube. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1979;58(1):101–4.

Sandhyamani S, Seth HN, Verma K. Intraepithelial involvement of endometrium, fallopian tube and vagina by cervical carcinoma. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1983;26(4):299–303.

Daniele E, Perino A, Catinella E. Superficial endometrial involvement by cervical intraepithelial neoplasia detected by intrauterine cytology. A case report. Acta Cytol. 1985;29(3):411–3.

Motoyama T, Watanabe H. Squamous cell carcinoma of the cérvix with extensive superficial spreading to almost whole genital tract and associated with endometrial stromal sarcoma. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1988;38:1445–52.

Teixeira M, de Magalhaes FT, Pardal-de-Oliveira F. Squamous-cell carcinoma of the endometrium and cervix. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1991;35(2):169–73.

Razquin S, Mayayo E, Antón E, Alvira R. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the endometrium as superficial extension of cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1993;35(3):190–2. https://doi.org/10.1159/000292698.

Pins MR, Young RH, Crum CP, Leach IH, Scully RE. Cervical squamous cell carcinoma in situ with intraepithelial extensions to the upper genital tract and invasion of tubes and ovaries: report of a case with human papilloma virus analysis. Int J Gynacol Pathol. 1997;16:272–8.

Agashe SR, Kulkarni MP, Momin YA, Sulhyan KR. Superficial extension of squamous cell carcinoma in situ of cervix involving endometrium, bilateral fallopian tubes and ovaries: a case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2007;50(2):375–7.

Adler F, Rabban JT, Yeh BM, Qayyum A, Chen L-M, Coakley FV. Superficial endometrial spread of squamous cell cervical carcinoma: a diagnostic challenge at magnetic resonance imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2007;31:247–50.

Yang SW, Kim WY, Cho SH, Yoon SH, Lim JY, Leet SJ. Multifocal microinvasive squamous cell carcinoma with extensive spread of squamous cell carcinoma in situ (CIS) into the uterine corpus, vagina, and left salpinx diagnosed five years after conization of cervical CIS. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2014;35(5):600–3.

Anthuenis J, Baekelandt J, Bourgain C, De Rop C. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ lining the uterine cavity. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2016;37:135–8.

Neelam S, Kumar S. Superficial spreading squamous cell carcinoma endometrium and icthyosis uteri with CINIII with p16 expression: report of 2 unusual cases. JKIMSU. 2017;6:126–31.

Muthusamy RK, Mehta SS. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the cervix with superficial intraepithelial extension to the endometrium of lower uterine segment: a rare presentation. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2017;38(1):88–9. https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-5851.203509.

Du J, Liao X. Superficial spreading squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the cervix involving the endometrium: a rare case presentation and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12(11):4162–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No source of funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JMV and JBL managed the case and compiled, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. PMB and PCP critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the fundamental principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

None of the authors have any potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Martín-Vallejo, J., Laforga, J.B., Molina-Bellido, P. et al. Superficial spreading cervical squamous cell carcinoma in situ involving the endometrium: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 16, 196 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-022-03433-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-022-03433-4