Abstract

Bacteria play vital roles in soil biological fertility; however, it remains poorly understood about their response to long-term fertilization in Chinese Mollisols, especially when organic manure is substituted for inorganic nitrogen (N) fertilizer. To broaden our knowledge, high-throughput pyrosequencing and quantitative PCR were used to explore the impacts of inorganic fertilizer and manure on bacterial community composition in a 35-year field experiment of Chinese Mollisols. Soils were collected from four treatments: no fertilizer (CK), inorganic phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) fertilizer (PK), inorganic P, K, and N fertilizer (NPK), and inorganic P and K fertilizer plus manure (MPK). All fertilization differently changed soil properties. Compared with CK, the PK and NPK treatments acidified soil by significantly decreasing soil pH from 6.48 to 5.53 and 6.16, respectively, while MPK application showed no significant differences of soil pH, indicating alleviation of soil acidification. Moreover, all fertilization significantly increased soil organic matter (OM) and soybean yields, with the highest observed under MPK regime. In addition, the community composition at each taxonomic level varied considerably among the fertilization strategies. Bacterial taxa, associated with plant growth promotion, OM accumulation, disease suppression, and increased soil enzyme activity, were overrepresented in the MPK regime, while they were present at low abundant levels under NPK treatment, i.e. phyla Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes, class Alphaproteobacteria, and genera Variovorax, Chthoniobacter, Massilia, Lysobacter, Catelliglobosispora and Steroidobacter. The application of MPK shifted soil bacterial community composition towards a better status, and such shifts were primarily derived from changes in soil pH and OM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mollisols (black soils) are widely distributed in the northeast of China and are considered to be highly fecund and productive (Wei et al. 2008). However, these soil have degenerated over time due to intensive fertilizer application (Liu et al. 2015). The widespread use of inorganic fertilizers has also reduced black soil quality and overall environmental health since large scale reclamation was initiated around the middle of the last century (Yin et al. 2015). Take soil OM for example, the original level of soil OM content on the top layer (0–20 cm) is about 10% or more, as soil OM accumulates faster than it is decomposed during the relative cold seasons (Wen and Liang 2001). After farming started, soil OM content drastically dropped to half of its original level in 20–30 years, and now stabilized at 2–4%. In addition, overuse of N fertilizer has caused soil acidification, as well as a reduction in soil microbial biomass and bacterial diversity (Guo et al. 2010). Our previous studies found that long-term N application changed the microbial community composition in black soils by reducing bacterial and fungal diversity and the bacteria to fungi ratio, which led to soil degradation (Zhou et al. 2015, 2016; Ding et al. 2016). Constant N input can also lead to changes in plant species composition and a loss of plant diversity (Clark et al. 2007). In response to soil degradation associated with excessive inorganic N fertilizer, reductions in inorganic N input have been advocated.

In contrast to inorganic N fertilizers, the benefits of organic fertilizer for agricultural production and soil fertility cannot be overemphasized. Organic fertilizer can increase soil organic carbon and total N (TN) (He et al. 2015), improve soil aggregate stability (Xie et al. 2015) and have residual N effects in subsequent years (Schröder et al. 2007). Manure, an important source of organic matter, can improve disordered bacterial community structures in soil that result from the overuse of inorganic fertilizer (Ai et al. 2015), thereby improving soil quality (Davidson 2009). Several studies have explored the influence of fertilization on plant communities, soil properties, microbial community structure, and microbial activity (Hallin et al. 2009; Ramirez et al. 2010; Wertz et al. 2012; Hartmann et al. 2013; Zhong et al. 2015). However, little is known about the overall impacts of different fertilization strategies on bacterial community composition, especially when manure is substituted for inorganic N fertilizer. In this study, soils were collected from a 35-year field experiment of Chinese Mollisols, which was ideal for investigating the effects of fertilization strategies on soil microorganisms (Geisseler and Scow 2014). We used high-throughput pyrosequencing and qPCR technology to describe soil bacterial community composition under organic manure and inorganic fertilizer regimes. Here, we hypothesize that (1) bacterial community composition and abundance differ among fertilization strategies due to altered soil properties, especially soil pH and OM; and (2) manure shifts soil bacterial communities towards a better status, whereas inorganic fertilizer has the opposite effect. In summary, understanding the responses of bacterial community composition to different fertilization strategies is an effective way to reveal the relationship between intensive fertilization and black soil degradation. The results highlight the potential use of manure for sustainable development in Chinese Mollisols.

Materials and methods

Field experiments and soil sampling

The field experiment, established in 1980, was located at the Heilongjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Heilongjiang Province, China (45°40′N, 126°35′E, altitude 151 m). The experiment was set up as a block design and each block was treated with different fertilizer strategies in triplicate: no fertilizer (CK), inorganic phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) fertilizer (PK), inorganic N, P and K fertilizer (NPK), and inorganic P and K fertilizer plus manure (MPK). Blocks were randomized into plots of 9 × 4 m. Doses of inorganic fertilizers were 75 kg ha−1 N (urea), 150 kg ha−1 P2O5, 75 kg ha−1 K2O and 18,600 kg ha−1 horse manure. Soils were collected from plant rows after soybean harvest in September 2014.

For each replicate plot, six cores were collected from the topsoil (5–20 cm) using a 3-cm diameter soil corer. Plant residue and gravel were removed and samples were mixed uniformly to form one composite sample. Each composite sample was divided into three parts. One part was stored at − 80 °C and the other two were used as two independent samples. Thus, a total of 24 soil samples were obtained for analyses.

Soil properties and soybean yield

Prior to chemical characterization, soil samples were air dried at room temperature and passed through a 2.0 mm sieve. Soil samples were diluted 1:1 in water and pH was measured using a pH meter. Soil OM was measured using the K2Cr2O7-capacitance method (Strickland and Sollins 1987). The Kjeldahl method was used to measure TN (Huang et al. 2007). NH4+–N and NO3−–N were tested according to Hart et al. (1994). Atomic absorption spectrometer and flame photometry were used to measure total K (TK) and available K (AK) (Helmke and Sparks 1996). The total P (TP) and available P (AP) were determined by colorimetric methods (Garg and Kaushik 2005) and resin extraction with modification (Hedley and Stewart 1982), respectively. Soybean yields were recorded after harvest.

High-throughput pyrosequencing and qPCR analysis

Total DNA was extracted using a MOBIO PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with modifications to the incubation step as previously described (Fierer et al. 2012b). For each of the 24 soil samples, six replicate extractions were combined together to obtain sufficient quantities of homogeneous DNA (Ding et al. 2016). DNA was purified, and then, DNA concentration and quality (A260/A280) of the extracts were estimated visually using a NanoDrop ND-1000 UVevis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Rockwood, TN, USA). The V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using primers 515F and 806R (Peiffer et al. 2013), which were designed to be universal for bacterial and archaeal taxa (Ramirez et al. 2012). Given the rare abundance of archaea (normally less than 1% of sequences), only the results for bacterial communities are presented. Illumina MiSeq Sequencing was carried out at the Personal Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China), according to the methods of Caporaso et al. (2012). The 16S rRNA gene sequences were submitted to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive with the Accession Number SRP 045472.

In spite of some inherent limitations, qPCR can be still used to estimate microbial abundance (Liu et al. 2015). The 515F/806R primer set was used for qPCR using an Applied Biosystems 7500 detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The reaction mixture (25 μL) and amplification conditions were performed according to the methods of Lauber et al. (2013) and Zhou et al. (2015). The qPCR was carried out in triplicate for each extracted DNA sample.

Bioinformatics and statistical analyses

Mothur software (v1.32, http://www.mothur.org/) was used to assemble pyrosequencing reads as described by Schloss et al. (2011). Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were identified using a cut-off of 97% similarity and were invalid in the case that less than four replicates were detected in one sample. Singletons, non-bacterial OTUs were removed, and the OTU abundance levels were normalized based on the sample with the least number of sequences. To perform a fair comparison between samples, all subsequent analyses were performed according to the normalized data (Zhou et al. 2016). The Ribosomal Database Project Naïve Bayesian rRNA classifier was used with a minimum percent identity threshold of 60% for taxonomic assignment (Li et al. 2014). Bacterial α-diversity (CHAO1, ACE and Shannon and Simpson indices) was calculated with ten times subsampling using Mothur software (v1.32). Weighted UniFrac distances were calculated and principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) was carried out to identify variations in bacterial community composition. Linear discriminant analysis coupled with effect size (LEfSe) was performed to identify significant differences in abundance of bacterial genera between MPK and NPK treatments (Segata et al. 2011). The linear discriminant analysis (LDA) score threshold was set to greater than 3.0. Relationships between bacterial community composition and soil properties were revealed by redundancy analysis (RDA) using CANOCO 5.0 software. Variance analysis of all experimental data was performed using SPSS (v.19). In all tests, P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Soil properties and soybean yields

The three fertilization strategies significantly increased concentrations of AP, AK, TP and TK (Table 1). Compared with CK, both NPK and MPK treatments increased the concentrations of NO3− and TN. NPK and PK significantly decreased soil pH from 6.48 to 5.53 and 6.16, respectively, while the MPK application alleviated soil acidification. Moreover, MPK treatment also had an accumulative effect on soil OM. In addition, soybean yields were significantly higher under the fertilization regimes, with the MPK application being the most effective strategy (2702 kg ha−1).

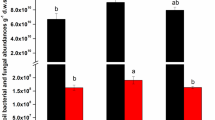

16S rRNA gene abundances

The effect of different fertilization strategies on 16S rRNA gene abundances was assessed. The number of gene abundances ranged from 8.69 × 109 to 1.59 × 1010 g−1 soil (Fig. 1). PK and MPK treatments significantly increased, whereas NPK treatment decreased the number of 16S rRNA gene abundances compared with CK.

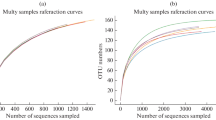

Bacterial α-diversity

A total of 538,485 high-quality sequences (70% of total sequences) were detected with an average read length of 270 bp. Based on a similarity cut-off of 97%, the minimum Good’s coverage value was 0.95, meaning that a sufficient number of reads were obtained to evaluate bacterial diversity. With regards to bacterial α-diversity (Table 2), NPK treatment significantly decreased CHAO1 and the Shannon indices in comparison with the other three treatments.

Bacterial community composition

Relative abundances at the phylum level (> 1%) are shown in Table 3. All samples were dominated by the phyla Proteobacteria, which accounted for 29.59–35.73% of the total sequences, followed by Acidobacteria (13.23–16.39%), Actinobacteria (9.26–10.83%), Verrucomicrobia (8.62–9.92%), and Planctomycetes (7.03–8.04%). MPK treatment resulted in the highest abundance of Proteobacteria. Moreover, the abundance of Bacteroidetes and Nitrospirae were also higher in MPK regime than those of NPK.

A total of 14 abundant classes (relative abundance > 1%) were identified (Table 4). Alphaproteobacteria, which represented 12.66–20.61% of the total sequences, was most abundant followed by Betaproteobacteria (6.74–10.48%), Actinobacteria (7.76–8.61%), Spartobacteria (6.75–8.36%) and Gemmatimonadetes (6.03–8.40%). NPK and MPK treatments significantly increased the relative abundance of Alphaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria. Betaproteobacteria abundance was lower in the three fertilization strategies compared with CK, with the lowest abundance observed in NPK. NPK application also caused a significant reduction in the abundance of Deltaproteobacteria. Compared with CK, NPK application increased abundance of Solibacteres, Thermoleophilia, Phycisphaerae, Acidobacteriia, and Gemmatimonadetes, whereas these classes were present at low levels in MPK treated samples. NPK treatment resulted in the lowest abundance of Nitrospira, whereas abundance was significantly increased in the MPK regime. Cluster analysis demonstrated that bacterial community composition of PK, MPK and CK treatments clustered into one group with a similarity of 98.85% that was separated from the NPK treatment (Fig. 2).

At the genus level, significantly different taxa (average relative abundance > 0.01%) were identified between NPK and MPK regimes (Fig. 3). Many bacterial genera were significantly more abundant in the NPK regime (e.g. Sphingomonas, Gemmatimonas, Bryobacter, Rhodanobacter, Xanthomonas, Nitrosospira, Mucilaginibacter, etc.), whereas other taxa were overrepresented in the MPK regime (e.g. Nitrospira, Blastocatella, Flexibacter, Chthoniobacter, Catelliglobosispora, Massilia, Variovorax, Steroidobacter, Lysobacter, etc.).

Bacterial taxa with significantly different abundances between NPK and MPK treatments. a Histogram of LDA scores for features with significantly different abundance between NPK and MPK treatments. b Taxonomic representation of statistically and biologically consistent differences between NPK and MPK treatments

Bacterial β-diversity

The results of PCoA analysis based on the weighted UniFrac distance matrix showed a clear separation between different fertilization strategies (Fig. 4). PC1, PC2 and PC3 explained 54, 12 and 5% of the variation, respectively. CK, PK and MPK plots were clustered together in the upper part, whereas the NPK plot was located separately in the bottom.

Principal components analysis of pyrosequencing reads obtained from soils treated with different fertilization strategies based on the weighted Fast UniFrac metric. The first three axes are drawn and the percent of variance explained by each axis is given. Treatment: (circle) CK, no fertilizer; (square) PK, inorganic phosphorus and potassium fertilizer; (triangle) NPK, inorganic P, K and N fertilizer; (star) MPK, inorganic P and K fertilizer plus manure

Relationship between bacterial community structure and soil properties

Based on RDA analysis, selected soil properties (soil pH, AP, AK, NH4+, NO3−, TK, TP, TN and OM) accounted for 54.2% of the variance of the model (Fig. 5). The first and second axes explained 28.54 and 7.5% of the total variation, respectively. Compared with NPK, CK, PK, and MPK treatments clustered together in the first and fourth quadrants, confirming the results of the cluster analysis. The selected soil properties affected the bacterial community composition in the following order: pH > OM > TN > AP > AK > TP > NO3− > TK.

Redundancy analysis (RDA) of soil bacterial composition and soil properties. Soil factors indicated in arrows include Avail P (available phosphorus), Avail K (available potassium), pH, NO3– (nitrate nitrogen), TN (total nitrogen), TK (total potassium), TP (total phosphorus) and OM (organic matter). Treatment: (star) CK, no fertilizer; (circle) PK, inorganic phosphorus and potassium fertilizer; (square) NPK, inorganic P, K and nitrogen fertilizer; (triangle) MPK, inorganic P and K fertilizer plus manure

Discussion

Inorganic PK plus manure application increased soybean yield and improved soil quality

Although all tested fertilization treatments increased soybean yield, MPK treatment was considered to be the optimal fertilization strategy, which were attributed to the slow release of manure nutrients into the soil (Zhao et al. 2014). PK treatment also resulted in higher soybean yield than NPK treatment, indicating a negative effect of inorganic N fertilizer. Indeed, high available N prevents plants from providing carbon for nutrient-absorbing systems (Wei et al. 2013). Inorganic N has also been shown to inhibit biological N fixation, which provides N needed for soybean growth (Gelfand and Robertson 2015).

In agreement with previous findings that the application of inorganic fertilizer alone can acidify soil (van Diepeningen et al. 2006), we found that both NPK and PK treatments significantly decreased soil pH. In particular, a decline of almost one pH unit was detected in response to NPK treatment in our study. In analysis and comparison of 10 long-term experimental fields, Guo et al. (2010) also found that significant soil acidification occurs in NPK-treated plots (P < 0.001). In contrast, MPK application had positive effects on the alleviation of soil acidification due to the buffering function of carbonates, bicarbonates, carboxyl and phenolic hydroxyl groups (Whalen et al. 2000; Garcia-Gil et al. 2004). Soil OM also accumulated in response to MPK treatment, which might be attributed to the macronutrient status of manure (Xie et al. 2014). Consequently, manure might stimulate the microbial biomass and increase soybean yield. With increased productivity, the amount of soybean residues returned to the soil after harvest also increases, leading to increased OM as residues decompose over time (Geisseler and Scow 2014). Overall, manure may be a potential substitute for inorganic N fertilizers for improvement of soybean growth and soil quality.

Inorganic PK plus manure application increased bacterial diversity

The number of 16S rRNA gene abundances was significantly different between the fertilization strategies. Compared with CK, MPK treatment significantly increased, whereas NPK treatment decreased the number of 16S rRNA gene abundances. Soil pH has been identified as a crucial factor in determining bacterial population dynamics (Zhou et al. 2015), since the optimal pH range for bacterial growth is limited (Rousk et al. 2010a). Ahn et al. (2012) also reported that bacterial abundance was correlated with soil pH.

There were no significant differences in CHAO1 and Shannon indices between CK, PK, and MPK regimes. However, similar to previous reports (Geisseler and Scow 2014; Zeng et al. 2016), NPK treatment significantly decreased these indices, indicating that inorganic N fertilizer has a greater influence than P or K on ecosystem instability (Chaer et al. 2009). Organic manure has been shown to have profound effects on bacterial population diversity (Naeem and Li 1997) and nutrient cycling rates (Philippot et al. 2013), which play an important role in microbial functions and processes (Chaer et al. 2009).

Inorganic PK plus manure application improved bacterial community composition

In the current study, Proteobacteria was the dominant phylum in all samples, which may be explained by the fact that members of this phylum can utilize a wide range of complex organic molecules and survive in various habitats (Bouskill et al. 2010). MPK treatment had the highest abundance of Proteobacteria, which were attributed to the greatest amount of soil nutrients available for copiotrophic bacterial growth (Fierer et al. 2012a). High abundance of Proteobacteria is particularly important for soybean growth, as members of this phylum have been shown to promote plant growth and facilitate horizontal transfer of genes related to photosynthesis (Makhalanyane et al. 2015). Additionally, many taxa within Proteobacteria had disease-suppression activity improving soil health (Mendes et al. 2011). Acidobacteria formed the second largest group in our dataset and was significantly lower in NPK and MPK regimes, which supported previous findings that oligotrophic bacteria such as Acidobacteria were negatively correlated with soil nutrients (Fierer et al. 2012a). Furthermore, MPK treatment significantly increased Bacteroidetes and Nitrospirae compared with NPK, indicating a positive effect on OM accumulation (Eilers et al. 2012) and nitrite oxidation (Cebron and Garnier 2005).

At the class level, bacterial community composition differed significantly among the fertilization treatments. Both NPK and MPK treatments significantly increased the abundance of Alphaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria, probably due to the highly nutritious soil (Ahn et al. 2012). Increased abundance of these classes may be beneficial for soil quality, as Alphaproteobacteria can use recalcitrant forms of carbon and supply carbon intermediates to other microorganisms (Campbell et al. 2010). Additionally, members of the class Gammaproteobacteria have been shown to defend plants from fungal disease by a putative chlorinated lipopeptide (Mendes et al. 2011). NPK application led to a higher abundance of Phycisphaerae than CK and MPK treatments, probably increasing the performance of nitrate removal (Xiao et al. 2015). In addition, higher abundances of Solibacteres and Thermoleophilia were detected in response to NPK treatment, which confirmed previous findings that these two classes are positively correlated with N addition (Zhou et al. 2017). Finally, with the decline of soil pH, Acidobacteriia abundance increased in the NPK regime, suggesting that soil environment was favorable to acidophilic, chemoorganotrophic bacteria (Wu et al. 2017b).

LEfSe analysis was performed to identify significantly different genera between NPK and MPK treatments. Genera with negative impacts on soil quality were overrepresented in the NPK regime, i.e. Sphingomonas, Xanthomonas, Rhodanobacter and Nitrosospira, while they were present at low levels in the MPK treatment group. Multiple species of Sphingomonas and Xanthomonas are considered animal and plant pathogens (White et al. 1996; Barak et al. 2016). Rhodanobacter is likely involved in the denitrifying process leading to N losses in low pH soil (Green et al. 2012). Furthermore, besides ammonia oxidation, members in Nitrosospira can perform nitrified denitrification, resulting in reduced conversion of nitrite to N2O and emission of greenhouse gas (Shaw et al. 2006). In addition, MPK treatment increased the abundance of beneficial genera, such as Variovorax, Chthoniobacter, Massilia, Lysobacter, Catelliglobosispora and Steroidobacter. Variovorax is considered to be a plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium (Jiang et al. 2012) and Chthoniobacter plays important roles in carbohydrate metabolism (Brewer et al. 2016). Species in Massilia and Lysobacter produce violacein (Myeong et al. 2016) and lytic enzymes (Li et al. 2008) that allow them to colonize plant roots and protect against infection by soil-borne plant pathogens (Ko et al. 2009; Ofek et al. 2012). Similarly, higher abundances of Catelliglobosispora and Steroidobacter in the MPK treatment group may indicate improved soil saccharase (Sun et al. 2014) and catalase activity (Sakai et al. 2014), respectively. However, Blastocatella and Nitrospira were also increased, suggesting an increase in ammonia oxidation (Alma et al. 2016) and nitrite oxidation through the nitrification process (Wu et al. 2016). Wu et al. (2017a) explored the effects of fertilizer application over a 20-year period on soil N transformation and found that inorganic fertilizer plus manure increased N mineralization rate and available soil N. However, in practical applications it should be considered that higher N nitrification is also induced by manure application, which may lead to increased N losses (Wu et al. 2017a).

Primary soil properties shape bacterial community composition

Soil microorganisms rapidly respond to changes in soil properties and these shifts can affect soil quality and plant growth (Marschner et al. 2003). In agreement with previous findings (Rousk et al. 2010b; Williams et al. 2013; Zhou et al. 2015), bacterial community composition was affected by soil pH and OM changes induced by long-term fertilization. Based on cluster and RDA analysis, the bacterial community composition of CK, PK and MPK treatment groups clustered together and were separated from NPK. Thus, inorganic N fertilizer input altered bacterial β-diversity. As Zhou et al. (2017) previously reported, long-term N application decreased soil pH and soil pH was highly correlated with UniFrac distance between bacterial communities. Soil pH plays a key role in shaping bacterial composition due the narrow pH range tolerated by most bacteria (Rousk et al. 2010a). Additionally, soil pH may indirectly affect bacterial community structure by responding to other variables and may provide an integrated index of soil conditions (Lauber et al. 2009). Hydrogen ion concentration varies by many orders of magnitude across various soils and, as numerous soil properties are related to soil pH, these factors may have driven the observed shifts in community composition (Xiong et al. 2012; Shen et al. 2013).

Abbreviations

- N:

-

nitrogen

- P:

-

phosphorus

- K:

-

potassium

- CK:

-

no fertilizer

- PK:

-

inorganic phosphorus and potassium fertilizer

- NPK:

-

inorganic phosphorus, potassium and nitrogen fertilizer

- MPK:

-

inorganic phosphorus and potassium fertilizer plus manure

- OM:

-

organic matter

- TN:

-

total nitrogen

- TK:

-

total potassium

- AK:

-

available potassium

- TP:

-

total phosphorus

- AP:

-

available phosphorus

- OTUs:

-

operational taxonomic units

- PCoA:

-

principal coordinates analysis

- LEfSe:

-

linear discriminant analysis coupled with effect size

- LDA:

-

the linear discriminant analysis

- RDA:

-

redundancy analysis

References

Ahn J, Song J, Kim B, Kim M, Joa J, Weon H (2012) Characterization of the bacterial and archaeal communities in rice field soils subjected to long-term fertilization practices. J Microbiol 50:754–765

Ai C, Liang G, Sun J, Wang X, He P, Zhou W, He X (2015) Reduced dependence of rhizosphere microbiome on plant-derived carbon in 32-year long-term inorganic and organic fertilized soils. Soil Biol Biochem 80:70–78

Alma TC, Serejo ML, Blanco S, Pérez R, Lebrero R, Muñoz R (2016) Photosynthetic biogas upgrading to bio-methane: boosting nutrient recovery via biomass productivity control. Algal Res 17:46–52

Barak JD, Vancheva T, Lefeuvre P, Jones JB, Timilsina S, Minsavage GV, Vallad GE, Koebnik R (2016) Whole-genome sequences of Xanthomonas euvesicatoria strains clarify taxonomy and reveal a stepwise erosion of type 3 effectors. Front Plant Sci 7:1805. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01805

Bouskill NJ, Barker-Finkel J, Galloway TS, Handy RD, Ford TE (2010) Temporal bacterial diversity associated with metal-contaminated river sediments. Ecotoxicology 19:317–328

Brewer TE, Handley KM, Carini P, Gilbert JA, Fierer N (2016) Genome reduction in an abundant and ubiquitous soil bacterium Candidatus Udaeobacter copiosus. Nat Microbiol 2:16198

Campbell BJ, Polson SW, Hanson TE, Mack MC, Schuur EAG (2010) The effect of nutrient deposition on bacterial communities in Arctic tundra soil. Environ Microbiol 12:1842–1854

Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Huntley J, Fierer N, Owens SM, Betley J, Fraser L, Bauer M, Gormley N, Gilbert JA, Smith G, Knight R (2012) Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J 6:1621–1624

Cebron A, Garnier J (2005) Nitrobacter and Nitrospira genera as representatives of nitrite-oxidizing bacteria: detection, quantification and growth along the lower Seine River (France). Water Res 39:4979–4992

Chaer G, Fernandes M, Myrold D, Bottomley P (2009) Comparative resistance and resilience of soil microbial communities and enzyme activities in adjacent native forest and agricultural soils. Microb Ecol 58:414–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-009-9508-x

Clark CM, Cleland EE, Collins SL, Fargione JE, Gough L, Gross KL, Pennings SC, Suding KN, Grace JB (2007) Environmental and plant community determinants of species loss following nitrogen enrichment. Ecol Lett 10:596–607. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01053.x

Davidson EA (2009) The contribution of manure and fertilizer nitrogen to atmospheric nitrous oxide since 1860. Nat Geosci 2:659–662. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo608

Ding J, Jiang X, Ma M, Zhou B, Guan D, Zhao B, Zhou J, Cao F, Li L, Li J (2016) Effect of 35 years inorganic fertilizer and manure amendment on structure of bacterial and archaeal communities in black soil of northeast China. Appl Soil Ecol 105:187–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2016.04.010

Eilers KG, Debenport S, Anderson S, Fierer N (2012) Digging deeper to find unique microbial communities: the strong effect of depth on the structure of bacterial and archaeal communities in soil. Soil Biol Biochem 50:58–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.03.011

Fierer N, Lauber CL, Ramirez KS, Zaneveld J, Bradford MA, Knight R (2012a) Comparative metagenomic, phylogenetic and physiological analyses of soil microbial communities across nitrogen gradients. ISME J 6:1007–1017. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.159

Fierer N, Leff JW, Adams BJ, Nielsen UN, Bates ST, Lauber CL, Owens S, Gilbert JA, Wall DH, Caporaso JG (2012b) Cross-biome metagenomic analyses of soil microbial communities and their functional attributes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109:21390–21395

Garcia-Gil JC, Ceppi SB, Velasco MI, Polo A, Senesi N (2004) Long-term effects of amendment with municipal solid waste compost on the elemental and acidic functional group composition and pH-buffer capacity of soil humic acids. Geoderma 121:135–142

Garg VK, Kaushik P (2005) Vermistabilization of textile mill sludge spiked with poultry droppings by an epigeic earthworm Eisenia foetida. Bioresour Technol 96:1063–1071

Geisseler D, Scow KM (2014) Long-term effects of mineral fertilizers on soil microorganisms-A review. Soil Biol Biochem 75:54–63

Gelfand I, Robertson GP (2015) A reassessment of the contribution of soybean biological nitrogen fixation to reactive N in the environment. Biogeochemistry 123:175–184

Green SJ, Prakash O, Jasrotia P, Overholt WA, Cardenas E, Hubbard D, Tiedje JM, Watson DB, Schadt CW, Brooks SC, Kostka JE (2012) Denitrifying bacteria from the genus Rhodanobacter dominate bacterial communities in the highly contaminated subsurface of a nuclear legacy waste site. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:1039–1047. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.06435-11

Guo JH, Liu XJ, Zhang Y, Shen JL, Han WX, Zhang WF, Christie P, Goulding KWT, Vitousek PM, Zhang FS (2010) Significant acidification in major Chinese croplands. Science 327:1008–1010. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1182570

Hallin S, Jones CM, Schloter M, Philippot L (2009) Relationship between N-cycling communities and ecosystem functioning in a 50-year-old fertilization experiment. ISME J 3:597

Hart SC, Stark JM, Davidson EA, Firestone MK (1994) Nitrogen mineralization, immobilization and nitrification. Methods Soil Anal Part 2 Microbiol Biochem Prop 2:985–1018

Hartmann AA, Barnard RL, Marhan S, Niklaus PA (2013) Effects of drought and N-fertilization on N cycling in two grassland soils. Oecologia 171:705–717

He YT, Zhang WJ, Xu MG, Tong XG, Sun FX, Wang JZ, Huang SM, Zhu P, He XH (2015) Long-term combined chemical and manure fertilizations increase soil organic carbon and total nitrogen in aggregate fractions at three typical cropland soils in China. Sci Total Environ 532:635–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.06.011

Hedley MJ, Stewart JWB (1982) Method to measure microbial phosphate in soils. Soil Biol Biochem 14:377–385

Helmke PA, Sparks DL (1996) Lithium, sodium, potassium, rubidium and cesium. Methods Soil Anal Part 3 Chem Methods 19:551–574

Huang B, Sun W, Zhao Y, Zhu J, Yang R, Zou Z, Ding F, Su J (2007) Temporal and spatial variability of soil organic matter and total nitrogen in an agricultural ecosystem as affected by farming practices. Geoderma 139:336–345

Jiang F, Chen L, Belimov AA, Shaposhnikov AI, Gong F, Meng X, Hartung W, Jeschke DW, Davies WJ, Dodd IC (2012) Multiple impacts of the plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium Variovorax paradoxus 5C-2 on nutrient and ABA relations of Pisum sativum. J Exp Bot 63:6421–6430. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ers301

Ko HS, De Jin R, Krishnan HB, Lee SB, Kim KY (2009) Biocontrol ability of Lysobacter antibioticus HS124 against Phytophthora blight is mediated by the production of 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid and several lytic enzymes. Curr Microbiol 59:608–615

Lauber CL, Hamady M, Knight R, Fierer N (2009) Pyrosequencing-based assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:5111–5120

Lauber CL, Ramirez KS, Aanderud Z, Lennon J, Fierer N (2013) Temporal variability in soil microbial communities across land-use types. ISME J 7:1641–1650

Li S, Jochum CC, Yu F, Zaleta-Rivera K, Du L, Harris SD, Yuen GY (2008) An antibiotic complex from Lysobacter enzymogenes strain C3: antimicrobial activity and role in plant disease control. Phytopathology 98:695–701

Li Y, Wen H, Chen L, Yin T (2014) Succession of bacterial community structure and diversity in soil along a chronosequence of reclamation and re-vegetation on coal mine spoils in China. PLoS ONE 9:e115024

Liu J, Sui Y, Yu Z, Shi Y, Chu H, Jin J, Liu X, Wang G (2015) Soil carbon content drives the biogeographical distribution of fungal communities in the black soil zone of northeast China. Soil Biol Biochem 83:29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.01.009

Makhalanyane TP, Valverde A, Gunnigle E, Frossard A, Ramond J-B, Cowan DA (2015) Microbial ecology of hot desert edaphic systems. FEMS Microbiol Rev 39:203–221

Marschner P, Kandeler E, Marschner B (2003) Structure and function of the soil microbial community in a long-term fertilizer experiment. Soil Biol Biochem 35:453–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-0717(02)00297-3

Mendes R, Kruijt M, de Bruijn I, Dekkers E, van der Voort M, Schneider JHM, Piceno YM, DeSantis TZ, Andersen GL, Bakker PAHM, Raaijmakers JM (2011) Deciphering the rhizosphere microbiome for disease-suppressive bacteria. Science 332:1097–1100. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1203980

Myeong NR, Seong HJ, Kim H-J, Sul WJ (2016) Complete genome sequence of antibiotic and anticancer agent violacein producing Massilia sp. strain NR 4-1. J Biotechnol 223:36–37

Naeem S, Li S (1997) Biodiversity enhances ecosystem reliability. Nature 390:507–509. https://doi.org/10.1038/37348

Ofek M, Hadar Y, Minz D (2012) Ecology of root colonizing Massilia (Oxalobacteraceae). PLoS ONE 7:e40117

Peiffer JA, Spor A, Koren O, Jin Z, Tringe SG, Dangl JL, Buckler ES, Ley RE (2013) Diversity and heritability of the maize rhizosphere microbiome under field conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110:6548–6553

Philippot L, Spor A, Hénault C, Bru D, Bizouard F, Jones CM, Sarr A, Maron P-A (2013) Loss in microbial diversity affects nitrogen cycling in soil. ISME J 7:1609–1619

Ramirez KS, Lauber CL, Knight R, Bradford MA, Fierer N (2010) Consistent effects of nitrogen fertilization on soil bacterial communities in contrasting systems. Ecology 91:3463–3470

Ramirez KS, Craine JM, Fierer N (2012) Consistent effects of nitrogen amendments on soil microbial communities and processes across biomes. Glob Chang Biol 18:1918–1927. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02639.x

Rousk J, Bååth E, Brookes PC, Lauber CL, Lozupone C, Caporaso JG, Knight R, Fierer N (2010a) Soil bacterial and fungal communities across a pH gradient in an arable soil. ISME J 4:1340–1351. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2010.58

Rousk J, Brookes PC, Bååth E (2010b) The microbial PLFA composition as affected by pH in an arable soil. Soil Biol Biochem 42:516–520

Sakai M, Hosoda A, Ogura K, Ikenaga M (2014) The growth of Steroidobacter agariperforans sp. nov., a novel agar-degrading bacterium isolated from soil, is enhanced by the diffusible metabolites produced by bacteria belonging to Rhizobiales. Microbes Environ 29:89–95

Schloss PD, Gevers D, Westcott SL (2011) Reducing the effects of PCR amplification and sequencing artifacts on 16S rRNA-based studies. PLoS ONE 6:e27310

Schröder JJ, Uenk D, Hilhorst GJ (2007) Long-term nitrogen fertilizer replacement value of cattle manures applied to cut grassland. Plant Soil 299:83–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-007-9365-7

Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS, Huttenhower C (2011) Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol 12:R60

Shaw LJ, Nicol GW, Smith Z, Fear J, Prosser JI, Baggs EM (2006) Nitrosospira spp. can produce nitrous oxide via a nitrifier denitrification pathway. Environ Microbiol 8:214–222

Shen C, Xiong J, Zhang H, Feng Y, Lin X, Li X, Liang W, Chu H (2013) Soil pH drives the spatial distribution of bacterial communities along elevation on Changbai Mountain. Soil Biol Biochem 57:204–211

Strickland TC, Sollins P (1987) Improved method for separating light-and heavy-fraction organic material from soil. Soil Sci Soc Am J 51:1390–1393

Sun J, Zhang Q, Zhou J, Wei Q (2014) Pyrosequencing technology reveals the impact of different manure doses on the bacterial community in apple rhizosphere soil. Appl Soil Ecol 78:28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2014.02.004

van Diepeningen AD, de Vos OJ, Korthals GW, van Bruggen AHC (2006) Effects of organic versus conventional management on chemical and biological parameters in agricultural soils. Appl Soil Ecol 31:120–135

Wei D, Yang Q, Zhang J, Wang S, Chen X, Zhang X, Li W (2008) Bacterial community structure and diversity in a black soil as affected by long-term fertilization. Pedosphere 18:582–592

Wei C, Yu Q, Bai E, Lü X, Li Q, Xia J, Kardol P, Liang W, Wang Z, Han X (2013) Nitrogen deposition weakens plant–microbe interactions in grassland ecosystems. Glob Chang Biol 19:3688–3697

Wen D, Liang W (2001) Soil fertility quality and agricultural sustainable development in the black soil region of northeast China. Environ Dev Sustain 3:31–43

Wertz S, Leigh AKK, Grayston SJ (2012) Effects of long-term fertilization of forest soils on potential nitrification and on the abundance and community structure of ammonia oxidizers and nitrite oxidizers. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 79:142–154

Whalen JK, Chang C, Clayton GW, Carefoot JP (2000) Cattle manure amendments can increase the pH of acid soils. Soil Sci Soc Am J 64:962–966

White DC, Sutton SD, Ringelberg DB (1996) The genus Sphingomonas: physiology and ecology. Curr Opin Biotechnol 7:301–306

Williams A, Börjesson G, Hedlund K (2013) The effects of 55 years of different inorganic fertiliser regimes on soil properties and microbial community composition. Soil Biol Biochem 67:41–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.08.008

Wu L, Nie Y, Yang Z, Zhang J (2016) Responses of soil inhabiting nitrogen-cycling microbial communities to wetland degradation on the Zoige Plateau, China. J Mt Sci 13:2192–2204

Wu Y, Shaaban M, Deng C, Peng Q, Hu R (2017a) Changes in the soil N potential mineralization and nitrification in a rice paddy after 20 years application of chemical fertilizers and organic matter. Can J Soil Sci 97:290–299

Wu Y, Zeng J, Zhu Q, Zhang Z, Lin X (2017b) pH is the primary determinant of the bacterial community structure in agricultural soils impacted by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon pollution. Sci Rep 7:40093

Xiao Y, Zheng Y, Wu S, Yang ZH, Zhao F (2015) Bacterial community structure of autotrophic denitrification biocathode by 454 pyrosequencing of the 16S rRNA gene. Microb Ecol 69:492–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-014-0492-4

Xie H, Li J, Zhu P, Peng C, Wang J, He H, Zhang X (2014) Long-term manure amendments enhance neutral sugar accumulation in bulk soil and particulate organic matter in a Mollisol. Soil Biol Biochem 78:45–53

Xie H, Li J, Zhang B, Wang L, Wang J, He H, Zhang X (2015) Long-term manure amendments reduced soil aggregate stability via redistribution of the glomalin-related soil protein in macroaggregates. Sci Rep 5:14687. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14687

Xiong J, Liu Y, Lin X, Zhang H, Zeng J, Hou J, Yang Y, Yao T, Knight R, Chu H (2012) Geographic distance and pH drive bacterial distribution in alkaline lake sediments across Tibetan Plateau. Environ Microbiol 14:2457–2466

Yin C, Fan F, Song A, Cui P, Li T, Liang Y (2015) Denitrification potential under different fertilization regimes is closely coupled with changes in the denitrifying community in a black soil. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:5719–5729. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-015-6461-0

Zeng J, Liu X, Song L, Lin X, Zhang H, Shen C, Chu H (2016) Nitrogen fertilization directly affects soil bacterial diversity and indirectly affects bacterial community composition. Soil Biol Biochem 92:41–49

Zhao J, Ni T, Li Y, Xiong W, Ran W, Shen B, Shen Q, Zhang R (2014) Responses of bacterial communities in arable soils in a rice-wheat cropping system to different fertilizer regimes and sampling times. PLoS ONE 9:e85301. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085301

Zhong Y, Yan W, Shangguan Z (2015) Impact of long-term N additions upon coupling between soil microbial community structure and activity, and nutrient-use efficiencies. Soil Biol Biochem 91:151–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.08.030

Zhou J, Guan D, Zhou B, Zhao B, Ma M, Qin J, Jiang X, Chen S, Cao F, Shen D, Li J (2015) Influence of 34-years of fertilization on bacterial communities in an intensively cultivated black soil in northeast China. Soil Biol Biochem 90:42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.07.005

Zhou J, Jiang X, Zhou B, Zhao B, Ma M, Guan D, Li J, Chen S, Cao F, Shen D, Qin J (2016) Thirty four years of nitrogen fertilization decreases fungal diversity and alters fungal community composition in black soil in northeast China. Soil Biol Biochem 95:135–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.12.012

Zhou J, Jiang X, Wei D, Zhao B, Ma M, Chen S (2017) Consistent effects of nitrogen fertilization on soil bacterial communities in black soils for two crop seasons in China. Sci Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-03539-6

Authors’ contributions

MO, JL and XJ conceived the experiments. MM, JZ and DW conducted the experiments and analyzed the results. MM, BZ and DG interpreted data. MO and WL edited the manuscript. And MM wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Wei-Qun Li of the Heilongjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences for fieldwork assistance. We also thank the University of Liège-Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech and more specifically the research platform AgricultureIsLife for the funding of the scientific stay in Belgium that made this paper possible.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Data will not be shared now and will be shared in future after completing full research on it.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 41573066 and 31200388), the National Key Basic Research Program of China (973 Program: 2015CB150506), the Fundamental Research Funds for Central Non-profit Scientific Institution (No. 1610132017010), and Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2015CL015).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, M., Zhou, J., Ongena, M. et al. Effect of long-term fertilization strategies on bacterial community composition in a 35-year field experiment of Chinese Mollisols. AMB Expr 8, 20 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-018-0549-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-018-0549-8