Abstract

Background

The association between bedside ventilatory parameters—specifically arterial carbon dioxide pressure (PaCO2) and ventilatory ratio (VR)—and mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) remains a topic of debate. Additionally, the persistence of this association over time is unclear. This study aims to investigate the relationship between 28-day mortality in ARDS patients and their longitudinal exposure to ventilatory inefficiency, as reflected by serial measurements of PaCO2 and VR.

Methods

We conducted a secondary analysis of four randomized controlled trials (FACTT, ALTA, EDEN, and SAILS) from the ARDS Network. All included patients were intubated and received mechanical ventilation. Patients were excluded if they underwent extracorporeal life support or were on mechanical ventilation for less than one day. The primary outcome was 28-day mortality. Bayesian joint models were employed to estimate the strength of associations over time.

Results

A total of 2,851 patients were included in our analysis. The overall 28-day mortality rate was 21.3%, with a median duration of invasive mechanical ventilation of 9 days (IQR: 4–28 days). After adjustment, each daily increment in PaCO2 (HR 1.008, 95% CI 0.997–1.018) was not associated with mortality, while a daily increment in VR (HR 1.548, 95% CI 1.309–1.835) was associated with increased mortality. This association persisted during the prolonged stages (Days 0–23) of mechanical ventilation. Furthermore, a significant increase in the risk of death was related to daily exposure to VR > 2 (HR 1.088 per day, 95% CI 1.034–1.147) and its cumulative effect (HR 1.085 per area, 95% CI 1.050–1.122), whereas PaCO2 was found to be insignificant.

Conclusion

VR, which reflects ventilatory inefficiency, should be closely monitored during invasive mechanical ventilation. Cumulative exposure to high intensities of VR may be associated with increased mortality in patients with ARDS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a life-threatening respiratory failure characterized by hypoxemia, and impaired clearance of carbon dioxide (CO2), with most patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation for support [1, 2]. The primary goals of mechanical ventilation in ARDS management are to maintain adequate oxygenation and ventilation [3, 4]. Clinically, oxygenation is typically assessed by the ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure to inspired fraction of oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) [1], while ventilation is primarily reflected by arterial carbon dioxide pressure (PaCO2), which depends on both CO2 production and alveolar ventilation. Despite its significance, the relationship between prolonged hypercarbia and prognosis in ARDS patients remains unresolved, with no consensus currently established [5, 6].

Ventilatory inefficiency, however, can manifest in clinical practice through increased PaCO2, elevated minute ventilation, or a combination of both. Therefore, a composite index, the ventilatory ratio (VR), which compares actual measurements of minute ventilation and PaCO2 to predicted values, has been proposed to better reflect ventilatory inefficiency [7]. Despite the potential of VR as a marker, previous studies investigating its association with ARDS prognosis have reported inconsistent results, likely due to limitations in sample sizes and the variability in controlling for confounding factors [8, 9]. Furthermore, findings from studies focusing on COVID-related ARDS may not be generalizable to the broader population of patients with classical ARDS due to differences in lung volume, respiratory mechanics, and ventilatory requirements [10,11,12]. Additionally, earlier researches on PaCO2 and VR often focused on single measurements upon admission or was restricted to the early phases of ARDS [5, 6, 12,13,14]. As a result, it remains unclear whether the relationship between ventilatory inefficiency and mortality in ARDS patients persists over time.

In this study, our primary objective was to evaluate the impact of time-varying exposure to ventilatory inefficiency—measured by PaCO2 and VR—on 28-day mortality in patients with ARDS. We also sought to determine whether the strength of these associations persisted over time and to quantify the cumulative impact of these exposures over the study period.

Methods

Study design and patients

We performed a secondary analysis of data from four published randomized controlled trials: FACTT (Fluid and Catheter Treatment Trial) [15, 16], ALTA (Albuterol for the Treatment of Acute Lung Injury) [17], EDEN (Early vs Delayed Enteral Nutrition in ARDS) [18], and SAILS (Statins for Acutely Injured Lungs) [19]. These trials focused on patients with classical ARDS and adhered to the low tidal volume ventilation protocol, reflecting current clinical practice standards. The details of these trials are summarized in Additional file 1: Table S1.

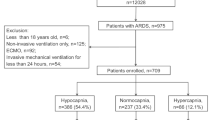

Included patients were adult subjects who were intubated and received mechanical ventilation. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Patients under the age of 18, (2) Patients lacking measurements of predicted body weight (PBW) or height needed to calculate VR, (3) Patients treated with extracorporeal life support, (4) Patients receiving invasive ventilation for less than one day, and (5) Patients lacking on-study ventilatory parameter measurements.

All studies obtained informed consent from patients and were approved by the respective institutional review boards. This study protocol, titled “The Association Between Time-Varying Intensity of Ventilatory Indices and Mortality in Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome,” was approved by the Research Ethics Commission of Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University (Approval ID: 2023ZDSYLL158-P01, 20,230,511). The commission determined that the activities involved in this research did not constitute human subjects research, thus waiving the requirement for informed consent. Data were obtained from the Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center (BioLINCC, https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov). This article complies with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for observational studies.

Data collection

In the ARDS Network trials, Day 0 was defined as the day of randomization following patient enrollment. Per trial protocol, patients were required to begin low tidal volume ventilation within one hour of meeting the inclusion criteria. Demographic data collected included age, gender, primary risk factors for ARDS, chronic comorbidities, and severity of illness as measured by the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) III score at admission.

Longitudinal data were collected for preselected variables, which were categorized under “on-study ventilator parameters.” These included arterial blood gases and ventilator parameters, which were recorded as close as possible to 08:00 AM on Days 0–4, 7, 12/14, 21, and 28 of mechanical ventilation. Ventilatory ratio is defined as [minute ventilation(mL/min) × PaCO2(mmHg)]/[PBW(kg) × 100(mL/min) × 37.5(mmHg)]. Data collection spanned from Day 0 until the earliest of the following events: death, discharge from the intensive care unit (ICU), liberation from mechanical ventilation for more than 48 h, or 28 days of ICU stay. The primary outcome of interest was 28-day mortality.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were summarized as proportions, while continuous variables were presented as means (standard deviations) or medians [interquartile ranges (IQRs)], depending on their distribution. Comparisons between groups were conducted using the Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables, and the Chi-squared (Χ2) test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate.

We first employed cause-specific Cox proportional hazard models to evaluate the relationship between baseline ventilatory parameters (PaCO2 and VR) and 28-day mortality. Restricted cubic splines were used within these models to express hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding two-sided 95% credible intervals (CIs). Based on the model outputs, we identified approximate thresholds for PaCO2 and VR.

Potential confounders were identified and assessed based on directed acyclic graphs (DAG) and change-in-estimate methods, while addressing collinearity and handling missing data to ensure robust and unbiased variable selection. (Additional file 1: Fig. S1-S2 & Table S2). The following covariates were selected for inclusion in the models:

-

Baseline confounders: Age, gender, body mass index (BMI), APACHE III score, comorbidities (Hypertension, Diabetes Mellitus, Chronic Pulmonary Disease), tidal volume per predicted body weight (PBW), positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), use of sedatives or neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs) (Yes/No), and use of vasopressors or inotropes(Yes/No).

-

Time-varying confounder: PaO2/FiO2.

To assess the association between longitudinal ventilatory parameters (PaCO2 and VR) and mortality, we utilized Bayesian joint models incorporating shared random effects. These models allow for the analysis of correlations between individual longitudinal profiles and 28-day mortality by accounting for non-random dropouts during follow-up. Shared parameter joint models combine mixed-effects models with Cox regression, linking patient-specific longitudinal trajectories to their prognosis. This approach assumes that latent random effects fully account for correlations between longitudinal exposures and outcomes after adjusting for covariates [20, 21].

Natural cubic splines were applied within both fixed-effects and random-effects models to accommodate any nonlinearity in the longitudinal exposure profiles. Estimations were performed using the JMbayes2 package, with additional details provided in Additional file 1 [22]. Standard Markov Chain Monte Carlo diagnostics were employed to assess model convergence [23], and the results were derived from the posterior distribution to predict the hazard of death within 28 days.

Given that the initial joint model assumed a constant strength of association over time, we incorporated an interaction term with a natural cubic spline of time to assess whether the association between ventilatory inefficiency and mortality persisted across time. We also explored the time-varying impact of daily high exposure to ventilatory inefficiency, defined as PaCO2 > 50 mmHg or VR > 2, on 28-day mortality. Additionally, we quantified the effect of cumulative exposure to elevated PaCO2 or VR by calculating the area beneath each subject’s longitudinal profile and above the specified thresholds, across the corresponding time period.

To mitigate bias resulting from missing data, we employed Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE), generating five imputed datasets to address the missing values. To verify the robustness of our findings, we repeated the joint model analyses using complete cases without imputation. We also performed subgroup analyses based on several factors, including age, gender, APACHE score, PaO2/FiO2 ratio, primary ARDS risk factors, and the use of sedatives or neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs), vasopressors or inotropes. For continuous variables, cut-off points were derived from existing knowledge or the interquartile ranges (IQRs). A P value < 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.1.2 (R Core Team 2021, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patients in the study

After reviewing data from 3027 patients, we included 2851 patients in the final analysis (Additional file 1: Fig. S3). The median age of the patients was 52 years (IQR 40–63), and 51.6% were male. The primary etiologies of ARDS were pneumonia (58.1%), sepsis (19.9%), and aspiration (11.4%). The median duration of invasive mechanical ventilation was 9 days (IQR 4–28 days), and the overall 28-day mortality rate was 21.3%.

Compared with survivors, non-survivors were older, had lower BMI, higher APACHE III scores, and were less likely to have received sedatives or NMBAs. In the cohort, tidal volumes were ≤ 8 mL/kg PBW in 1886 patients (79.0%), accounting for missing values (Additional file 1: Table S2). On Day 0 of mechanical ventilation, plateau pressures ≤ 30 cmH2O and driving pressures ≤ 15 cmH2O were observed in 1,542 patients (80.2%) and 952 patients (49.6%), respectively. Importantly, there were no significant differences in peak inspiratory pressure or driving pressure between survivors and non-survivors (Table 1).

Association of mortality with ventilatory parameters at baseline

A U-shaped relationship was identified between PaCO2 or VR and the risk of 28-day mortality. Inefficient ventilation, indicated by hypercapnia (PaCO2 > 50 mmHg) or high VR (VR > 2), was associated with an increased hazard of death within 28 days after adjustment (Fig. 1A and Fig. 1B). After adjusting for multiple covariates, including age, gender, BMI, APACHE III score, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, chronic pulmonary disease), tidal volume per PBW, PEEP, use of sedatives or NMBAs, use of vasopressors or inotropes, and PaO2/FiO2, only the ventilatory ratio (VR) at baseline remained significantly associated with mortality (HR 1.101, 95% CI 1.009–1.201). PaCO2, on the other hand, was not significantly associated with mortality after adjustment (HR 1.003, 95% CI 0.995–1.011) (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Outcomes in relation to ventilatory parameters at baseline. A Adjusted hazard ratio for 28-day mortality predicted by baseline PaCO2 using a cause-specific Cox proportional hazard model. B Adjusted hazard ratio for 28-day mortality predicted by baseline ventilatory ratio using a cause-specific Cox proportional hazard model. PaCO2 arterial carbon dioxide pressure

Of the total cohort, 2769 patients (97.1%) had complete PaCO2 data on Day 0, with 12.4% of patients experiencing impaired carbon dioxide clearance (PaCO2 > 50 mmHg). Additionally, 2673 patients (93.8%) had complete VR data on Day 0, and 38.4% of patients had a VR > 2. Significant variations in patient characteristics and interventions were noted based on PaCO2 and VR levels at baseline (Additional file 1: Tables S4-S5).

Effect of time-varying intensities of ventilatory parameters

In the joint model analysis, time-varying ventilatory ratio (VR) (HR 1.548, 95% CI 1.309–1.835) was significantly associated with an increased risk of death after adjusting for covariates. In contrast, time-varying PaCO2 (HR 1.008, 95% CI 0.997–1.018) showed no significant association with mortality, consistent with the results from the baseline cause-specific Cox proportional hazard model (Table 2).

The lack of a significant correlation between PaCO2 intensity and mortality persisted throughout the entire ventilation period, as illustrated in Fig. 2A. By contrast, VR was consistently associated with 28-day mortality over the course of mechanical ventilation, as shown in Fig. 2B. Traceplots and density plots confirmed good convergence of the joint models (Additional file 1: Fig. S4-S5).

Cumulative effect of exposure to high intensities of ventilatory inefficiency

The risk of mortality increased consistently with daily exposure to PaCO2 > 50 mmHg and VR > 2. Each additional day of exposure to elevated VR (> 2) was associated with a heightened risk of death after adjustment (HR 1.088 per day, 95% CI 1.034–1.147). However, prolonged exposure to high PaCO2 levels (> 50 mmHg) did not show a significant effect on mortality (HR 1.040 per day, 95% CI 0.979–1.104) (Table 3).

Additionally, a cumulative impact of higher intensities of ventilatory inefficiency was observed. An increased risk of mortality was linked to a larger cumulative area of VR > 2 (HR 1.085 per area, 95% CI 1.050–1.122) after adjustments. Conversely, cumulative exposure to PaCO2 > 50 mmHg did not significantly influence 28-day mortality (HR 1.002 per area, 95% CI 0.999–1.004) (Additional file 1: Table S6).

Subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses

Subgroup analyses explored the relationship between time-varying hypercapnia and high VR with 28-day mortality (Fig. 3). The association between high VR and mortality appeared to be more pronounced in patients with lower severity of illness, as indicated by an APACHE III score ≤ 91 (HR 1.112 per day, 95% CI 1.012–1.218) or PaO2/FiO2 > 150 (HR 1.088 per day, 95% CI 1.011–1.169). Regarding hypercapnia, the hazard of death was elevated in patients receiving sedatives or neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs) (HR 1.073 per day, 95% CI 1.016–1.134) and in those receiving vasopressors or inotropes (HR 1.127 per day, 95% CI 1.030–1.232).

Subgroup analyses of the association between any exposure to hypercapnia or high VR. The hazard ratios were the adjusted hazard ratios comparing higher versus lower levels of the variable. PaCO2 arterial carbon dioxide pressure, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, APACHE Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, PaO2/FiO2 ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure to inspired fraction of oxygen, NMBAs neuromuscular blocking agents

To test the robustness of our initial findings, we repeated the joint model analyses after excluding patients with missing longitudinal data on PaCO2 and VR during follow-up. The results from the complete datasets were consistent with those derived from imputed datasets (PaCO2: HR 1.073, 95% CI 0.998–1.158 vs. VR: HR 1.088, 95% CI 1.021–1.164), confirming the reliability of our findings (Additional file 1: Table S7).

Discussion

In clinical practice, ventilation assessment has often been overshadowed by the emphasis on oxygenation during mechanical ventilation in patients with ARDS. Indices such as PaCO2 and the ventilatory ratio (VR), which are readily available and indicative of ventilatory inefficiency, have not been fully appreciated and require more attention in clinical studies [24]. Our study highlights the longitudinal relationship between PaCO2, VR, and 28-day mortality, suggesting that clinicians should attach importance to VR throughout the period of mechanical ventilation. We also found that time- and dose-dependent exposure to high levels of ventilatory inefficiency, as measured by VR > 2, rather than PaCO2 > 50 mmHg, was associated with increased mortality in ARDS.

PaCO2, a frequently monitored parameter linked to alveolar ventilation, can rise due to ventilatory inefficiency or hypoventilation. Ventilatory inefficiency indicated by hypercapnia showed no significant association with ARDS prognosis when compared to VR. A possible explanation for this discrepancy is the beneficial effects of permissive hypercapnia in patients undergoing lung-protective ventilation [25]. By tolerating elevated PaCO2 levels, permissive hypercapnia mitigates acute lung injury through reduced mechanical stretch and anti-inflammatory effects [26, 27]. Moreover, hypercapnia improves ventilation-perfusion matching by enhancing bronchodilation and hypoxic vasoconstriction, contributing to better pulmonary and systemic oxygenation [28].

The dimensionless VR is widely recognized as a marker for assessing pulmonary dead space [29]. Increased pulmonary dead space reflects the lungs' inefficiency in eliminating CO2, which can lead to hypercapnia. Given that the anatomical portion of dead space is generally constant, increasing tidal volumes (VT) with a stable respiratory rate would increase alveolar ventilation, effectively lowering PaCO2. This tradeoff is captured by VR [30]. Ventilatory inefficiency, reflected by high VR(VR > 2) is independently associated with increased case fatality in patients with ARDS [31]. The utility of VR for quantifying physiological dead space, however, may be limited by factors such as venous admixture and the CO2 production [9]. As such, VR serves as a measure of global gas exchange efficiency and allows the quantification of ventilation-perfusion mismatch [29]. VR shows promise as a simple method to stratify ARDS patients that is not captured by conventional oxygenation indices.

We further attempted to address ARDS heterogeneity through subgroup analyses. The stronger association between higher VR and mortality in less severe cases, as indicated by APACHE III and PaO2/FiO2 scores, appears exploratory in nature, consistent with previous study [32]. A higher VR in these cases may reflect an early maladaptive response to underlying pathophysiological processes, such as subtle respiratory muscle fatigue or early ventilation-perfusion mismatch. In contrast, in patients with more severe disease, elevated VR may simply be a marker of overall critical illness, where multiple organ systems are already compromised [33]. This could dilute the specific impact of VR on mortality. Future prospective and interventional studies, guided by focused hypotheses and mechanistic insights, are needed to better understand the clinical significance of VR across varying severities of ARDS.

Our study has important implications for interpreting previous research. First, we extended the assessment period between VR and its association with mortality, capturing its dynamic evolution over the course of the ventilation. Second, Bayesian joint models were employed in our study to account for both baseline and time-varying confounders, offering a more precise estimation of temporal associations. Third, we identified clinically meaningful thresholds for VR > 2—aligning with evidence from previous studies [8, 31]. Finally, the larger sample size in our study enhances the statistical power, improving the robustness and external validity of the observed relationships. Overall, our results emphasize the role of VR in prognostication and highlight the importance of adequately powered studies in this area.

Several limitations of our study should be acknowledged. First, the study is a retrospective observational analysis based on datasets from four randomized controlled trials. This design introduces inevitable challenges, such as missing values and the inability to infer causality. Second, our dataset consists of arterial blood gas and ventilator data collected at a standardized time each morning. It is possible that these measurements were not taken simultaneously or did not fully capture the ventilatory parameters throughout the day. To address these limitations, a prospective study is warranted to confirm these findings and explore their potential implications for clinical interventions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, ventilatory inefficiency, as reflected by VR, is associated with increased mortality in patients with ARDS undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation. Long-term exposure to high VR levels correlates with higher mortality, underscoring the importance of vigilant monitoring. However, given the retrospective design, these findings suggest an association rather than causation and warrant further validation through well-designed prospective studies.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available from the Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and can be accessed at https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/home/.

Abbreviations

- ALTA:

-

Albuterol for the Treatment of Acute Lung Injury

- APACHE:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Credible intervals

- CO2 :

-

Carbon dioxide

- COVID:

-

Coronavirus disease

- DAG:

-

Directed acyclic graph

- EDEN:

-

Early vs Delayed Enteral Nutrition in ARDS

- FACTT:

-

Fluid and Catheter Treatment Trial

- HR:

-

Hazard ratios

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

Interquartile ranges

- MICE:

-

Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations

- NMBAs:

-

Neuromuscular blocking agents

- PaCO2 :

-

Arterial carbon dioxide pressure

- PaO2/FiO2 :

-

Arterial oxygen partial pressure to inspired fraction of oxygen

- PBW:

-

Predicted body weight

- PEEP:

-

Positive end-expiratory pressure

- SAILS:

-

Statins for Acutely Injured Lungs

- VR:

-

Ventilatory ratio

References

Definition Task Force ARDS, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526–33.

Fan E, Del Sorbo L, Goligher EC, Hodgson CL, Munshi L, Walkey AJ, et al. An official American thoracic society/European society of intensive care medicine/society of critical care medicine clinical practice guideline: mechanical ventilation in adult patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(9):1253–63.

Radermacher P, Maggiore SM, Mercat A. Fifty years of research in ARDS. Gas exchange in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(8):964–84.

Pelosi P, Ball L, Barbas CSV, Bellomo R, Burns KEA, Einav S, et al. Personalized mechanical ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):250.

Madotto F, Rezoagli E, McNicholas BA, Pham T, Slutsky AS, Bellani G, SAFE Investigators and the ESICM Trials Group, et al. LUNG Patterns and impact of arterial CO(2) management in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: insights from the LUNG SAFE study. Chest. 2020;158(5):1967–82.

Nin N, Muriel A, Peñuelas O, Brochard L, Lorente JA, Ferguson ND, VENTILA Group, et al. Severe hypercapnia and outcome of mechanically ventilated patients with moderate or severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(2):200–8.

Sinha P, Fauvel NJ, Singh S, Soni N. Ventilatory ratio: a simple bedside measure of ventilation. Br J Anaesth. 2009;102(5):692–7.

Sinha P, Calfee CS, Beitler JR, Soni N, Ho K, Matthay MA, et al. Physiologic analysis and clinical performance of the ventilatory ratio in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(3):333–41.

Maj R, Palermo P, Gattarello S, Brusatori S, D’Albo R, Zinnato C, et al. Ventilatory ratio, dead space, and venous admixture in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Br J Anaesth. 2023;130(3):360–7.

Pozzi T, Collino F, Brusatori S, Romitti F, Busana M, Moerer O, et al. Specific respiratory system compliance in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;208(3):328–30.

Liu X, Liu X, Xu Y, Xu Z, Huang Y, Chen S, et al. Ventilatory ratio in hypercapnic mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(10):1297–9.

Beloncle F, Studer A, Seegers V, Richard JC, Desprez C, Fage N, et al. Longitudinal changes in compliance, oxygenation and ventilatory ratio in COVID-19 versus non-COVID-19 pulmonary acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):248.

Morales-Quinteros L, Neto AS, Artigas A, Blanch L, Botta M, Kaufman DA, PRoVENT-COVID Study Group, et al. Dead space estimates may not be independently associated with 28-day mortality in COVID-19 ARDS. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):171.

Torres A, Motos A, Riera J, Fernández-Barat L, Ceccato A, Pérez-Arnal R, CIBERESUCICOVID Project (COV20/00110, ISCIII), et al. The evolution of the ventilatory ratio is a prognostic factor in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 ARDS patients. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):331.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Thompson BT, Schoenfeld D, Wiedemann HP, de Boisblanc B, et al. Pulmonary-artery versus central venous catheter to guide treatment of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(21):2213–24.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Thompson BT, Hayden D, de Boisblanc B, et al. Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2564–75.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Matthay MA, Brower RG, Carson S, Douglas IS, Eisner M, Hite D, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of an aerosolized β₂-agonist for treatment of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(5):561–8.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, Steingrub J, Hite RD, Moss M, et al. Initial trophic vs full enteral feeding in patients with acute lung injury: the EDEN randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307(8):795–803.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute ARDS Clinical Trials Network, Truwit JD, Bernard GR, Steingrub J, Matthay MA, Liu KD, Albertson TE, et al. Rosuvastatin for sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2191–200.

Rizopoulos D. Joint models for longitudinal and time-to-event data: with applications in R. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2012.

Rizopoulos D, Ghosh P. A Bayesian semiparametric multivariate joint model for multiple longitudinal outcomes and a time-to-event. Stat Med. 2011;30:1366–80.

Rizopoulos D, Papageorgiou G, Afonso PM. JMbayes2: Extended joint models for longitudinal and time‐to‐event data. 2023. https://drizopoulos.github.io/JMbayes2/

Rizopoulos D. The R package JMbayes for fitting joint models for longitudinal and time-to- event data using MCMC. J Stat Softw. 2016;72:46.

Siddiki H, Kojicic M, Li G, Yilmaz M, Thompson TB, Hubmayr RD, et al. Bedside quantification of dead-space fraction using routine clinical data in patients with acute lung injury: secondary analysis of two prospective trials. Crit Care. 2010;14(4):R141.

Laffey JG, O’Croinin D, McLoughlin P, Kavanagh BP. Permissive hypercapnia–role in protective lung ventilatory strategies. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):347–56.

Laffey JG, Tanaka M, Engelberts D, Luo X, Yuan S, Tanswell AK, et al. Therapeutic hypercapnia reduces pulmonary and systemic injury following in vivo lung reperfusion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(6):2287–94.

Ijland MM, Heunks LM, van der Hoeven JG. Bench-to-bedside review: hypercapnic acidosis in lung injury–from ‘permissive’ to ‘therapeutic.’ Crit Care. 2010;14(6):237.

Marhong J, Fan E. Carbon dioxide in the critically ill: too much or too little of a good thing? Respir Care. 2014;59(10):1597–605.

Verscheure S, Massion PB, Verschuren F, Damas P, Magder S. Volumetric capnography: lessons from the past and current clinical applications. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):184.

Ferluga M, Lucangelo U, Blanch L. Dead space in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6(19):388.

Kaku N, Nakagama Y, Shirano M, Shinomiya S, Shimazu K, Yamazaki K, et al. Longitudinal ventilatory ratio monitoring for COVID-19: its potential in predicting severity and assessing treatment response. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):366.

Monteiro ACC, Vangala S, Wick KD, Delucchi KL, Siegel ER, Thompson BT, NHLBI PETAL Network, et al. The prognostic value of early measures of the ventilatory ratio in the ARDS ROSE trial. Crit Care. 2022;26(1):297.

Morales-Quinteros L, Schultz MJ, Bringué J, Calfee CS, Camprubí M, Cremer OL, MARS Consortium, et al. Estimated dead space fraction and the ventilatory ratio are associated with mortality in early ARDS. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9(1):128.

Acknowledgements

This secondary analysis was prepared using data from the FACTT, ALTA, EDEN, and SAILS research materials, conducted by the ARDS Network and obtained from the Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). The article does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the researchers who conducted these trials or those of the NHLBI. We acknowledge the exceptional work by the ARDS Network researchers, without whom this study would not have been possible.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Plan (2022YFC2504400 & 2021YFC2500804), and the Jiangsu Provincial Key Research and Development Program (BE2022854).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LLJ and YY conceived the study and conceptualized the research aims. LLJ, HC, and JFX designed the study and contributed to ensuring the accuracy of the data analysis. HC, ZSW, and YY contributed to the acquisition of the data. LLJ, WC, QS, and XYY took responsibility for the integrity of the data. LLJ conducted the formal analysis and drafted the manuscript. LL and YY supervised the manuscript review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is a secondary analysis of four randomized controlled trials, each of which received approval from the institutional review board (IRB) at the respective study centers. All data used in this analysis were de-identified in the datasets provided. Therefore, the requirement for ethical approval and informed consent was waived for this manuscript.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

13613_2025_1427_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1:A. Additional Methods: 1. Data collection. 2. Approach to missing data. 3. Bayesian joint model. B. Additional Results: Table S1 Characteristics of enrolled clinical trials. Table S2 Percentage of missing data in the baseline and dynamic cohort. Table S3 Adjusted hazard ratios of cause-specific Cox proportional model at baseline. Table S4 Baseline characteristics of patients stratified by PaCO2. Table S5 Baseline characteristics of patients stratified by ventilatory ratio. Table S6 The effect of cumulative exposure to hypercapnia or high VR on mortality. Table S7 The effect of time-varying exposure to hypercapnia or high VR after excluding missing data. Fig. S1 Directed acyclic graph illustrating the potential confounders on the association of ventilatory parameters and mortality. Fig. S2 Correlation matrix for baseline (A) and dynamic (B) covariates. Fig. S3 Study flow diagram in the present study. Fig. S4 Diagnostic plot of the joint model based on PaCO2. Fig. S5 Diagnostic plot of the joint model based on ventilatory ratio

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, L., Chen, H., Chang, W. et al. Time-varying intensity of ventilatory inefficiency and mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann. Intensive Care 15, 6 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-025-01427-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-025-01427-1