Abstract

Background

This study evaluates the psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the Nine-Item Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Screen (NIAS) in a population of Turkish adolescents.

Method

The NIAS, designed to screen for ARFID symptoms, including picky eating, fear-related eating behaviors, and low appetite, was administered to secondary school students between 13 and 18 ages in Muğla, Turkiye.

Results

Based on a sample of 268 adolescents, the NIAS’s reliability and validity in this demographic are supported. The research utilized confirmatory factor analysis to verify its three-factor structure and various reliability tests, including Cronbach’s alpha and test-retest reliability, confirming the scale’s internal consistency and temporal stability. The descriptive analysis highlighted significant differences in NIAS scores across BMI categories, with underweight adolescents scoring higher, suggesting a potential link between ARFID symptoms and lower body weight. Criterion validity was supported by significant correlations between NIAS subscales and measures of anxiety, depression, and eating behaviors, indicating the scale’s effectiveness in reflecting relevant psychopathological features.

Conclusion

Overall, the study establishes the Turkish NIAS as a useful tool for identifying ARFID in Turkish adolescents, aiding early detection and intervention in this at-risk age group. Further research is recommended to explore the scale’s utility across different clinical settings and refine its diagnostic accuracy, enhancing our understanding of ARFID’s impact on youth mental health and nutritional status.

Plain English summary

Cross-culturally reliable tools for assessing symptoms of Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) in young people are crucial, especially during adolescence, a critical period for the emergence of various eating and feeding disorders. The Nine Item Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Screen (NIAS) is a brief and practical instrument designed to assess and rate symptoms across three phenotypes associated with ARFID: ‘picky eating,’ ‘fear,’ and ‘appetite,’ which can lead to restricted food volume or variety. This study, focusing on a sample of Turkish adolescents, validates the reliability and accuracy of the NIAS in this particular demographic. The findings offer a foundational understanding of the ARFID profile among Turkish adolescents. The psychometric robustness of the NIAS in self-reporting among adolescents is demonstrated by significant correlations between its subscales and other measures of anxiety, depression, and eating behaviors, indicating that the scale effectively captures related psychopathological traits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is a psychiatric disorder with a heterogeneous clinical presentation that results in a volumetrically restricted diet as a result of limiting dietary variety and/or restricting dietary intake due to avoidance of certain foods or food groups [1]. In ARFID, restriction in dietary diversity and volume leads to failure to meet appropriate nutritional and/or energy needs, resulting in (1) weight loss, failure to achieve age-appropriate growth, (2) nutritional deficiencies, (3) continuous need for nutritional supplements to meet daily energy requirements, (4) significant impairment of psychosocial functioning. ARFID, which was previously included under the heading of “Feeding Disorder of Infancy or Early Childhood,” has been reformulated and taken its new place in the “Feeding and Eating Disorders” group in DSM-5 [1]. This change has provided a new framework for classifying, assessing, and treating individuals with food restriction/avoidance who do not meet previously defined criteria for eating or feeding disorders. Importantly, it underscores that symptoms of ARFID can persist across the lifespan, necessitating ongoing management and support [2, 3].

Restrictive food problems are the most common eating disorders in children and adolescents [4, 5]. DSM-5 includes three restrictive eating disorder classifications: Anorexia Nervosa-Restrictive (AN-R), Anorexia Nervosa-Atypical (AN-A), and ARFID. Although these groups are similar regarding very restricted food intake, weight loss, and slowed growth, the underlying causes and clinical features of the three disorders are quite different [1]. Patients in the ARFID group lack the preoccupation with body image, the fear of gaining weight, or the urge to be thin compared to those in the AN group. Rather, food restriction is driven by aversive reactions—or a lack of positive hedonic reactions—to food itself or the act or short-term aftermath of eating. The underlying three main behavioral drivers in the ARFID group are as follows: (a) lack of interest in eating and/or low appetite; (b) rejection and/or avoidance of trying new foods and discomfort with sensory characteristics of foods such as smell, taste, texture and appearance (selective/ neophobic eating) and (c) fear of the aversive consequences of eating (e.g., vomiting, choking or abdominal pain) [1]. These mechanisms also constitute the three prototypical subgroups of ARFID. Patients may present with only one of these subgroups or in combination [4].

Apart from the underlying mechanisms, there are also differences in clinical features between ARFID and other restrictive eating disorders [6]. In clinical samples of patients seeking specialized eating disorder treatment at tertiary centers, ARFID occurs at an earlier age [7,8,9], more frequently in males [10, 11] or with an equal frequency between males and females [12, 13], has a longer duration of illness before diagnosis [9, 14], and is more frequently accompanied by medical comorbidity [14, 15] compared to other restrictive eating disorders. It was also found that anxiety disorder [11, 15] and neurodevelopmental disorders [16] were more frequently associated with ARFID than other eating disorders, but depressive disorder [7, 14] was less frequent in young people diagnosed with ARFID. However, differential rates of depression may be driven by the age differences between patients with ARFID and other eating disorders in most clinical samples [17].

Since ARFID is a relatively new diagnosis compared to other eating disorders, epidemiologic studies in both general and clinical populations are limited [6]. The majority of studies have been conducted in specialized eating disorder services, and prevalence rates in these studies have been shown to range between 5 and 22.5% [7, 9,10,11, 18]. Although less numerous, studies in specialized nutrition clinics have reported the highest prevalence rates of 32–64% [16, 19, 20]. Studies conducted on community samples show that prevalence rates vary between 0.3% and 15.5% [12, 13, 21,22,23]. In a surveillance study conducted on children and adolescents aged 5–18 years in Canada, the incidence of ARFID was 2.02 per 100.000 patients (95% Cl, 1.76–2.31) [15]. The variability in prevalence rates across studies and insufficient incidence data demonstrate the importance of using robust and cross-culturally valid screening and assessment tools for ARFID [24].

Semi-structured tools such as the Eating Disorder Assessment-ARFID Module for DSM-5 (EDA-5) [25], Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5) [26], and Pica, ARFID, and Rumination Disorder Interview (PARDI) [27] can be used to assess the presence and severity of ARFID symptoms. However, their routine use can be costly and time-consuming, and these are not ARFID-specific tools [28]. Eating Disturbances in Youth Questionnaire (EDY-Q) [29], Nine Item Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Screen (NIAS) [30], and the recently developed Pica, ARFID and Rumination Disorder Interview ARFID Questionnaire (PARDI-AR-Q) [28] are self-report scales used in the assessment of ARFID. While EDY-Q has shown acceptable discriminant, divergent, and convergent validity in general population samples, it still needs to be validated in clinical samples. The EDY-Q’s convergent and divergent validity was confirmed by its associations with ChEDE-Q items. Additionally, the EDY-Q demonstrated discriminant validity in relation to BMI differences. Moreover, since PARDI-AR-Q is a new scale, its validation was conducted on a relatively small and heterogeneous sample [28]. This study assessed the PARDI-AR-Q for convergent validity using the NIAS subscales, the FNS, and the CIA. Divergent validity was evaluated using the EDE-Q, and concurrent validity was assessed using the PARDI interview.

The NIAS, a brief and practical tool, offers a straightforward approach to screening and rating symptoms of three phenotypes (i.e., “picky eating,” “fear,” and “appetite”) that may trigger food volume or variety restriction in ARFID [30]. A study conducted on a large sample in America demonstrated that NIAS may have strong psychometric properties and has shown convergent, divergent, and discriminant validity [30]. Zickgraf et al. [30] assessed the divergent validity of the NIAS from other eating disorder symptoms using the EAT-26 scale and its convergent validity using the AEBQ scales, which are related to appetite characteristics. The International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement recently concluded a review of patient-reported outcome measures for eating disorders and identified the NIAS as the recommended outcome tracking measure for ARFID [31]. Studies have shown that the NIAS-self report does not discriminate well between individuals with ARFID and individuals with eating disorders (especially restrictive eating disorders) caused by shape/weight concerns and that the NIAS-self report has a high score in all eating disorders. These results suggest that the NIAS-self report may have the potential to be used as a transdiagnostic restrictive ED screener [32,33,34].

Although the NIAS has been translated into many languages [35,36,37,38] and validation studies have been carried out, including Turkish, the measure has not yet been validated in Turkish youth. Given the earlier age of onset for ARFID compared to other eating disorders, having cross-culturally valid tools for the assessment of ARFID symptoms in young people is essential as it will help identify those at risk during adolescence when susceptibility to all eating and feeding disorders increases markedly [39]. Therefore, this study aimed to validate the Turkish version of the NIAS-self-report in adolescents in the community sample. We hypothesized that the Turkish version of the NIAS-self report will: (1) replicate patterns of three-factor structure validity observed in the original version in the community sample of adolescents, (2) have good psychometric properties (factor structure, reliability, and convergent and divergent validity), and (3) demonstrate similar patterns of correlations between NIAS subscales and body mass index percentile, measures of weight/shape-related disordered eating, anxiety, depression symptoms, and eating behaviors in adolescents as the adult self-report NIAS (e.g., [30]).

Methodology

Participants

The research sample consists of secondary school and high school students (between 8th grade and 12th grade) in Muğla, Turkiye, in the 2022–2023 academic year. The inclusion criteria for the study were determined as being between the ages of 13 and 18 and agreeing to participate, and no exclusion criteria were applied to the study. To prevent selection bias, the participants to be included in the study were determined by a blinding method by Muğla Guidance and Research Center. Participants were recruited from selected schools using a non-random, appropriate sampling method. The initial pool consisted of 400 students, out of which 132 did not agree to participate in the study. Consequently, the final study sample included 268 adolescents. Among them, 153 (57.09%) of the adolescents were girls, 115 (42.91%) were boys, and the average age of the adolescents was 15.7 ± 1.48 years. The participants included students from 8th grade to 12th grade: 35 (13.06%) 8th graders, 30 (11.19%) 9th graders, 40 (14.92%) 10th graders, 86 (32.09%) 11th graders, and 77 (28.73%) 12th graders. Mean weight was 60.16 kg (± 13.82), height was 166.95 cm (± 9.71), Body Mass Index (BMI) was 21.77 (± 4.84), and percentile values were 51.64 (± 30.73).

For test-retest reliability, 80 randomly selected adolescents were asked to re-answer the NIAS four weeks after the initial administration. Fifty-four adolescents (67.5%) responded to the scale again.

Procedure

First, permission was received via e-mail from the scale developers to adapt the NIAS self-report form to Turkish adolescents. Then, an ethics committee application was made to the Social Sciences University of Ankara Institutional Ethics Committee of Social Sciences and Humanities Research and Publication, and approval was received (Date / No: 03.01.2023 / 62,667). In the first adaptation stage, the scale was translated into Turkish independently by two Turkish clinical psychologists with advanced knowledge of English. A consensus was then reached after a discussion between the authors of the article and the clinical psychologists who translated it. Subsequently, a professional translator who was bilingual and independent of the study translated the Turkish version of the scale back into English. The translated version of the scale was reviewed by its developer, and some minor changes were made to avoid ambiguity. Finally, the scale was applied to ten randomly selected adolescents, misunderstandings identified by the authors of the article were corrected, and the Turkish version of the scale was given its final form. The final version of the items preserved the original scale’s arrangement, number of items, sequence, and rating scale.

Data were collected through “Survey Monkey” (an online survey platform). The first page of the created survey included the content and objectives of the study in detail. Informed consent was obtained from the adolescents and their parents. Participants were included in the study voluntarily, and no payment was made to them. In the survey, adolescents were asked to report their age, gender (pre-defined categories), height, and weight data and to fill out the NIAS, Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire-Short (EDE-QS), Adult Eating Behavior Questionnaire (AEBQ) and Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS).

Measurements

Nine-item Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Screen (NIAS)

The NIAS, a self-report scale developed by Zickgraf & Ellis (2018) [30], is structured to evaluate ARFID symptoms through three distinct subscales: Picky Eating, Appetite, and Fear. The scale is composed of nine items in the 6-point Likert type, with 1–3 items assigned to the “Picky Eating,” 4–6 items to the “Appetite,” and 7–9 items to the “Fear” subscales. Each item is scored from 0 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scores of these items are then summed, with each subscale’s score ranging from 0 to 15. A higher total score (0–45) indicates a more pronounced avoidant/restrictive eating. In the original study of the scale in adults in the United States, the NIAS demonstrated good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent/discriminant validity, suggesting its relevance in evaluating selective/neophobic eating, Appetite, Fear, and ARFID-like symptoms. In the original study, Cronbach’s α value for the NIAS total score to assess internal reliability was 0.90 [30].

Eating disorder examination-questionnaire short (EDE-QS)

The EDE-QS [40], a brief version of the EDE-Q, was developed by Gideon et al. [41] to measure the core symptoms of eating disorders. This single-factor scale, consisting of 12 items, evaluates the frequency of eating disorder symptoms (such as AN, Bulimia nervosa, and eating disorder not otherwise specified symptoms) experienced in the past week. Each item of the EDE-QS is scored on a scale from 0 (0 days/ not at all) to 3 (6–7 days/ Markedly). These scores are then added up, ranging from 0 to 36, with higher scores indicating more severe eating disorder symptoms. The EDE-QS was derived from the original 36-item EDE-Q [41], translated into Turkish, and validated in adolescents [42]. In this study, the EDEQ-S was included to assess divergent validity with a measure of disordered eating other than ARFID. While the original study reported a Cronbach’s α value of 0.91 [41], this study yielded a Cronbach’s α value of 0.89.

The revised child anxiety and depression scale-child version (RCADS)

The scale was developed by Chorpita et al. [43] to evaluate the self-reported symptoms of depressive disorder and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents and has been translated into Turkish and validated in a clinical sample of Turkish adolescents [44]. The RCADS, which consists of 47 items and is a four-point Likert type, is scored as 0 (never) and 3 (always). The survey consists of six subscales, and these subscales are respectively; separation anxiety disorder (SPAD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and major depressive disorder (MDD). The response values for each subscale are summed to calculate the subscale scores. Then, using a conversion table, this raw summary score is converted into a standardized “T-score” for the appropriate gender and grade level. This scale was included to assess the relationship between the Appetite, Picky Eating, and Fear subscales of the NIAS and symptoms of anxiety and depression. The Cronbach’s α for the 47 items ranged from 0.73 to 0.91. in the original study [43]. In the present sample, Cronbach’s α coefficients for the subscales ranged from 0.64 to 0.88.

Adult eating behaviour questionnaire (AEBQ)

The AEBQ is a self-report scale developed by Hunot et al. [45] to assess adult eating behavior related to food approach and food avoidance. AEBQ, which consists of 35 items and is a five-point Likert type, is scored as 1 (strongly disagree) and 5 (strongly agree); some items are reverse-scored. AEBQ consists of seven subscales, with 3–5 items in each scale [46]: Food Responsiveness (FR), Emotional Over-Eating (EOE), Enjoyment of Food (EF), Satiety Responsiveness (SR), Emotional Under-Eating (EUE), Food Fussiness (FF), and Slowness in Eating (SE). Subscales FR, EOE, and EF evaluate the food approach, while SR, EUE, FF, and SE assess symptoms related to food avoidance. Subscale scores were calculated using the mean of the items for each scale. The measure was translated into Turkish and validated in an adult sample [47]. Although yet to be validated in Turkish adolescents, the validity of the AEBQ for adolescent respondents has been demonstrated for the English and Polish language translations of the measure [48, 49]. In this study, subscales related to food approach were included to assess their divergent validity with Appetite, and subscales related to food avoidance were included to evaluate their convergent validity with Appetite. Additionally, FF was included to examine its convergent validity with Picky Eating. In the present sample, Cronbach’s α coefficients for the subscales ranged from 0.66 to 0.94.

Body mass index (BMI)

Participants reported their subjective weight (kg) and height (m), which were used to compute BMI. BMI was calculated using the formula kg/m2. Then, BMI percentiles were determined according to the age and gender of the participants using the World Health Organization (WHO) growth charts. Based on the recommended cut-off points of BMI percentiles for Turkish adolescents [50] (i.e., < 5 percentiles = underweight, 5–85 percentiles = normal weight,> 85 percentiles = overweight/ obese), 69 had BMI (25.7%) in the underweight range, 121 (45.1%) in the healthy weight range, and 78 (29.1%) in the overweight/ obese range. The BMI percentiles of the adolescents were used in the study because the values were related to the A.1 criterion (weight loss/ failure to achieve age-appropriate growth due to restrictive eating) of ARFID diagnosis according to DSM-5.

Data analysis

The statistical procedures for scale adaptation were performed using JASP (2020) [51] software. JASP is software based on the R (R Core Team, 2021) [52] program that utilizes R packages [53]. Differences in NIAS subscale scores and total scores in terms of gender were evaluated using Student’s t-test, and differences in BMI percentiles were evaluated using ANOVA. Post hoc analysis (Bonferroni) was performed to determine the source of the difference between the groups in cases where a significant difference was detected in terms of BMI percentiles.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to test the construct validity. CFA analysis used the “maximum likelihood with robust standard errors” estimator. For the CFA analysis at scale, the JASP program uses the “lavaan” [54], “semPlot” [55], and “psych” [53] packages based on the CFA analysis assumptions in Brown (2014) [56] and Kline’s (2015) (35) books. Fit indices were evaluated as a result of CFA, according to recommended values for an adequate model fit based on the literature: Chi-squared statistic/degrees of freedom (χ2/df) < 5, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08; Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI) > 0.90 [57], Comparative Fit Index (CFI) ≥ 0.95, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) ≤ 0.08 [58, 59], Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) ≥ 0.90 [58]. (55,56)

Pearson correlation test was used to examine the relationship between “Picky eating,” “Fear,” and “Appetite” subscale scores of NIAS, EDE-QS, AEBQ, and RCADS scores and adolescent’s BMI percentiles.

Lower-upper group reliability, item-total correlation, test-retest, and Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficient were used for the reliability analysis. The lower-upper group reliability evaluates the difference between the mean item scores of the upper 27% and lower 27% groups formed according to the total scores obtained from the measurement tool. The lower-upper group reliability was evaluated using Student’s t-test. Item-total correlation and test-retest were performed using Pearson’s correlation test. The mean values of items were expressed with standard deviation, and results with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Factor analysis of the NIAS

During the adaptation process of the self-report version of the NIAS scale in adolescents, detailed descriptive statistics were calculated for each item. These statistics include each item’s mean and standard deviation values on the scale. The averages of the items of the NIAS ranged from 1.75 to 3.82. These values are presented in detail in Table 1.

Construct validity

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

A first-order CFA was conducted to determine the structural validity as part of adapting the NIAS scale to the Turkish language. The three-factor structure of the measurement tool was confirmed through the CFA results of the NIAS self-report scale. All fit indices were consistent with good fit (χ2 = 47.31, df = 24, χ2/df = 1.97; RMSEA = 0.06 [0.034, 0.085]; CFI = 0.965; TLI = 0.948; SRMR = 0.046). The factor loadings for each item were significant, with standardized loadings ranging from 0.54 to 0.82. Moreover, the residual covariances of the items were acceptable (0.30-0.70). The results of the CFA and factor loadings relevant to the scale are provided in Table 2.

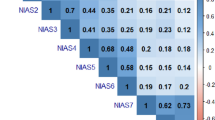

Upon examining Table 3, it can be observed that the covariances between dimensions were calculated in the CFA for the NIAS scale. The covariance between Picky eating and Appetite was 0.67, and between Appetite and Fear was 0.48, which were statistically significant. The covariance between picky eating and fear was lower at 0.09 but was statistically insignificant.

Descriptive analysis of the NIAS

Table 4 shows the defined and compared results according to the BMI percentile category and gender on the three subscales and full-scale score of NIAS. Specifically, for BMI, underweight adolescents showed significantly higher scores on the NIAS full-scale score, the Picky eating, and the Appetite subscales than those in the healthy weight and overweight/obese range (η2 = 0.03, η2 = 0.03, η2 = 0.04, respectively). There was no significant difference in genders except for the Fear subscale and total score, with girls’ higher scores associated with a small effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.37, Cohen’s d = 0.29, respectively).

Criterion validity

The criterion validity of NIAS in adolescents was evaluated according to the correlation between the Picky Eating, Appetite, and Fear subscale scores and BMI percentage values, AEBQ, EDE-QS, and RCADS scores.

While there was a small-moderate and negative correlation between NIAS-Appetite and BMI percentile, there was no significant relationship between BMI percentile and NIAS-Picky eating and NIAS-Fear. Considering the relationship between the appetite trait evaluated AEBQ and NIAS-Appetite, there were positive and significant correlations with the three food avoidance subscales (SR, SE, and EUE) and positive but small correlations with FF. Also, NIAS-Appetite had negative and significant relationships with the three food approach subscales (FR, EOE, and EF). Relative to the other subscales of the NIAS, NIAS-Picky eating had the strongest and most positive association with the AEBQ-FF subscale. While NIAS-Picky eating had a null relationship with FR, it had a relationship with other subscales of AEBQ in the same direction as NIAS-Appetite but with a smaller effect size. NIAS-Fear had a null relationship with EOE, EUE, and FR, a positive and significant relationship with SR, FF, and SE, and a negative and significant relationship with EF. While the NIAS-Fear subscale had a small-moderate and positive relationship with the EDE-S self-report, the other subscales did not show a significant relationship with non-ARFID eating disorder symptoms.

All three subscales were positively and significantly associated with total depression and anxiety symptoms in RCADS. NIAS-Picky Eating and NIAS-Appetite demonstrated a small-moderate and positive relationship with the MDD subscale, while NIAS-Fear exhibited a positive-small relationship with the same subscale. Furthermore, the study found that only NIAS-Picky eating had a significant relationship with the OCD subscale of RCADS. Conversely, NIAS-Fear was found to have a significant relationship with the GAD subscale. Additionally, the study reported a null relationship between the SAD subscale and NIAS-Appetite, while the other two subscales (NIAS-Picky Eating and NIAS-Fear) exhibited small, positive relationships with SAD subscale. All three subscales had positive and significant correlations with PD and SPAD. The NIAS criterion validity results are shown in Table 5.

Reliability analysis of the NIAS

Internal consistency

The Cronbach α coefficient was used to determine the internal consistency of this scale. The calculation resulted in Cronbach’s α coefficients of 0.75 for the NIAS overall scale, 0.75 for Picky Eating, 0.66 for Appetite, and 0.81 for Fear. Cronbach’s α values of the scale concluded that the overall scale, as well as the Picky Eating and Fear subscales, demonstrate good internal consistency. In contrast, the Appetite subscale shows acceptable internal consistency [60]. The results of the Cronbach α are given in Table 1.

Item analysis

According to the reliability analysis results of the scale, item-total correlations vary between 0.45 and 0.63 for Picky Eating, 0.37 and 0.41 for Appetite, and 0.45 and 0.63 for Fear. The item analysis of the NIAS self-report showed that the items on the relevant scale are of high quality and distinctiveness and are measured in the same dimension. The results of the analysis are given in Table 1.

Distinguishing features of ıtems (lower-upper group reliability)

Another criterion indicating the reliability of the scale is the difference between the responses of the lower and upper groups to the items. Since the lower 27% and upper 27% groups are expected to differ in terms of the measured characteristic, there is expected to be a significant difference between the mean item scores of the groups formed according to the total scores obtained from the measurement tool. This method can determine the scale’s discriminative power [61]. The t-test was performed to determine the significance of the difference between the mean item scores of the upper 27% (N:73) and lower 27% (N:73) groups taken from the total study population. The t-test results showed a significant difference (p < 0.001) between the lower and upper groups (Table 1). According to these results, NIAS items have good discrimination.

Test-retest

NIAS scale’s test-retest reliability was assessed by collecting data from 54 participants at two different time points, with an interval of four weeks between the tests. The correlation results indicate strong positive correlations between the test and retest measures for Picky Eating (r = 0.87, p < 0.001), Appetite (r = 0.78, p < 0.001), Fear (r = 0.89, p < 0.001), and total score (r = 0.85, p < 0.001).

Discussion

In this study, the psychometric properties of NIAS self-report in Turkish adolescents aged 13–18 years were examined, and the relationship between NIAS subscales and BMI percentile, weight/shape-related disordered eating, anxiety, depression symptoms, and eating behaviors was investigated. This demonstrated that the Turkish version of the NIAS-self report had good factor structure, convergent and divergent validity, internal consistency, item-total correlations, and test-retest reliability. In addition, this study provides the first insight into the ARFID profile of Turkish adolescents.

The CFA results of the NIAS-self-report scale confirmed the measurement tool’s three-factor structure and nine items (CFI = 0.965, RMSEA = 0.06). In addition, the scale’s three-factor structure, consisting of Picky eating, Fear, and Appetite, supported the ARFID subtypes in DSM-5, similar to the original scale [30].

Reliability analysis of the Turkish version of the NIAS-self report provided evidence of good internal consistency, item-total correlations, distinguishing features of items, and test-retest reliability. Cronbach’s α value for the total score of NIAS was 0.90 in the original study. Similarly, it was 0.86, 0.88, 0.84, and 0.88 in the Chinese [37], Mexican [35], Arabic [62], and Polish [36] versions, respectively. In this study, Cronbach’s α value of 0.75 for the overall scale NIAS was similar to other studies, and its internal consistency was sufficient. Additional reliability analyses conducted in this study showed that the scale items have high quality and distinctiveness, that the scale items measure the same dimension, and that the responses are consistent over time. The strong correlations between the initial assessment and retest of the NIAS subscales and total scores in the adolescent sample indicate high stability and consistency of responses over time, as in the adult sample [30, 37]. Hence, this study provides further evidence of the good psychometric properties of the NIAS in Turkish adolescents.

In our study, while there was a relationship between low BMI percentile and NIAS-Appetite, this relationship was not shown between NIAS-Picky eating and NIAS-Fear. In comparisons between weight groups, the Appetite and Picky eating subscale scores of underweight adolescents were higher than those of normal and high-weight adolescents. The results found for the Appetite subscale in adults were consistent with the original study [30] and other studies conducted in Western countries [45, 46, 63] and the Arab population [62] and were expected. Higher picky eating and total NIAS scores in underweight adolescents were seen only in China, and this difference was attributed to cultural factors and the higher prevalence of underweight, relative to US samples, eliminating a potential floor effect [37]. It can be understood that Appetite symptoms, in which there is limited motivation to eat by hunger and/or enjoyment and the resulting volume restriction, are generally associated with underweight and/or normal vs. overweight/obesity across cultures. The heterogeneous clinical appearance of selective/neophobic eaters, from severe weight loss to healthy weight and even high weight, in studies conducted in different countries supports the effect of culturally changing eating environments [64, 65]. Studies conducted in various cultures and environments will help better understand ARFID characteristics among other weight groups. However, even within the same food environment, individual differences in food preferences, accommodation and structure from the family or school, and the use of high-calorie nutritional supplements or calorie boosting (a Criterion A symptom of ARFID) can explain the heterogeneity of weight in subclinical and clinical ARFID cases.

Appetitive traits are individual differences in the tendency to increase or decrease food intake in response to internal and external stimuli, and/or the characteristics of available food, which appear at an early age relative to disordered eating symptoms, are moderate to strongly heritable [66]. Some appetitive traits may be risk factors for eating disorders. Consistent with previous literature in the adult population [30, 37], significant and negative correlations were found between NIAS-Appetite and all food approach subscales. In contrast, significant and positive correlations were found between NIAS-Appetite and all food avoidance subscales. The fact that people who get full faster, enjoy less, and eat slower tend to have lower BMI shows that these appetitive traits are risk factors for ARFID-Appetite [30, 67]. Additionally, while it was negatively related to self-reports of eating enjoyment and the NIAS-Picky eating subscale, it was positively associated with self-reports of satiety responsiveness, slowness in eating, emotional undereating, and especially food fussiness. Unlike other appetitive traits, food fussiness is related to food selection, not energy intake. This strong relationship between NIAS-Picky eating and food fussiness shows that it is consistent with the selective/neophobic (discomfort with sensory characteristics of food and food neophobia) ARFID symptoms defined in DSM-5 [1]. As in other studies in children and adolescents, the NIAS-Fear subscale was unrelated or less related to appetitive traits than the other two subscales [65, 68]. This may be because food neophobia/selectivity and appetite are trait-like and early emerging, impacting food intake that appears early and exists on a wide spectrum of clinical significance, but ARFID-Fear symptoms appear acutely and later due to the condition [69].

Except for NIAS-Fear, no other subscales were found to be significantly related to EDEQ-S. This small positive association between symptoms of fear of negative consequences of eating, such as choking, vomiting, and gastrointestinal pain, and symptoms of restrictive eating disorders due to overvaluation of weight/shape was also shown in the original study in adults [30]. As a result of NIAS validation studies conducted with samples seeking treatment for eating disorders, including adults and only children and adolescents, the following conclusions were reached: (a) NIAS can classify ARFID into three clinical presentations based on underlying triggering causes (b) NIAS-self report is a very practical and useful tool in the screening of restrictive eating disorders (c) Subscale and total NIAS scores cannot distinguish ARFID from other restrictive eating disorders (d) Using the NIAS together with another eating disorder scale, such as the EDEQ-S, may help differentiate ARFID and non-ARFID eating disorders [32, 70].

Identifying psychiatric diseases accompanying ARFID is essential in understanding transdiagnostic structures that pose risks and can be targeted in treatment [71]. Studies on psychiatric comorbidities seen with ARFID are limited, and the results vary. Studies conducted on clinical samples of children and adolescents have reported that the frequency of psychiatric comorbidity varies between 57% and 95% [11, 72], and at least 10% have more than one additional psychiatric disorder [73]. It has been shown that anxiety disorders (36–72%) [7, 11] accompany ARFID more frequently than depressive disorders (17–33%) followed by neurodevelopmental disorders (3–26%) [7, 74]. In this study, all subscales of the NIAS had a positive relationship with the RCADS total anxiety and depression score. It has been reported that individuals with the ARFID-Picky eating profile, as well as adolescents with the ARFID-Fear profile, have high comorbidities with anxiety disorders [68]. Here, it is thought that individuals with both profiles exhibit avoidance behavior to relieve anxiety, and avoidance functions as a negative reinforcer [71]. That is, avoidance behavior may be the transdiagnostic construct of ARFID and anxiety disorders, and avoidance-oriented intervention in treatment may help alleviate symptoms in both diseases [75]. Additionally, this study showed that NIAS-Picky eating had a positive and strong relationship with depression and OCD symptoms, as well as anxiety symptoms. These findings are consistent with research suggesting that picky eating is associated with adverse clinical outcomes in ARFID and may be a transdiagnostic indicator for psychiatric diseases [76, 77]. Overall, our findings underscore the commonality of comorbid psychopathology among individuals with ARFID and related presentations and also highlight the potential for shared psychopathology between specific ARFID profiles and other psychiatric disorders to represent transdiagnostic constructs that may be relevant treatment targets.

Some limitations need to be considered when interpreting this study’s findings. Data on adolescents were obtained from a web-based and non-clinical sample. Additionally, adolescents from a single region in western Turkiye were included in the study. This may limit the generalization of current findings. The fact that self-report scales were applied to adolescents in the study suggests that the results may be affected by recall and social desirability biases. Supporting the findings with a structured interview will help determine clinical cut-offs on the Turkish NIAS-self report. Another limitation is using the AEBQ, validated in Turkish adults, for criterion validity in this study. This study obtained adolescents’ height and weight based on self-reports. Overweight and obese adolescents have been shown to have more bias and variability in self-reported weight than normal/underweight adolescents [78]. However, despite these limitations, the conclusions of the study are important because this is one of the limited studies that only evaluated ARFID symptoms in a community sample of adolescents and provides findings regarding the relationship of all three ARFID phenotypes with anxiety, depression symptoms, and eating behaviors and shows that the NIAS-self report is a robust measure in the assessment of symptoms in Turkish adolescents.

Conclusion

This study makes a unique contribution to the understanding of ARFID in Turkish adolescents. It demonstrates that the NIAS-self report is a brief, practical, valid, and reliable scale to screen for ARFID in the general population of this culturally rich and unique region that forms a geographical bridge between the West and the East. The study provides a psychometrically sound and reliable Turkish version of the NIAS, and presents data on the ARFID profiles of adolescents in Turkiye and their relationship with other psychiatric disorders. This unique cultural setting offers a new perspective to evaluate the cross-cultural validity of the NIAS scale and the ARFID construct. To further enhance our understanding, future research should be expanded by including clinical samples to identify individuals at risk for ARFID, determine ARFID prevalence rates, and calculate NIAS cut-off values.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

American Psychiatric Association. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Wash DC. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.744053.

Bryant-Waugh R, Kreipe RE. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in DSM-5. Psychiatr Ann. 2012;42:402–5.

Brigham KS, Manzo LD, Eddy KT, Thomas JJ. Evaluation and treatment of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) in adolescents. Curr Pediatr Rep. 2018;6:107–13.

Norris ML, Spettigue WJ, Katzman DK. Update on eating disorders: current perspectives on avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in children and youth. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016:213–8.

Lucarelli L, Sechi C, Cimino S, Chatoor I. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: a longitudinal study of malnutrition and psychopathological risk factors from 2 to 11 years of age. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1608.

Sanchez-Cerezo J, Nagularaj L, Gledhill J, Nicholls D. What do we know about the epidemiology of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in children and adolescents? A systematic review of the literature. Eur Eat Disorders Rev. 2023;31:226–46.

Nicely TA, Lane-Loney S, Masciulli E, Hollenbeak CS, Ornstein RM. Prevalence and characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in a cohort of young patients in day treatment for eating disorders. J Eat Disord. 2014;2:1–8.

Norris ML, Robinson A, Obeid N, Harrison M, Spettigue W, Henderson K. Exploring avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in eating disordered patients: a descriptive study. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47:495–9.

Forman SF, McKenzie N, Hehn R, Monge MC, Kapphahn CJ, Mammel KA, et al. Predictors of outcome at 1 year in adolescents with DSM-5 restrictive eating disorders: report of the national eating disorders quality improvement collaborative. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:750–6.

Wong L, Goh LG, Ramachandran R. Evolution of paediatric eating disorders in Singapore: a historical cohort study. Arch Dis Child. 2022;107:1046–8.

Cooney M, Lieberman M, Guimond T, Katzman DK. Clinical and psychological features of children and adolescents diagnosed with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in a pediatric tertiary care eating disorder program: a descriptive study. J Eat Disord. 2018;6:1–8.

Dinkler L, Yasumitsu-Lovell K, Eitoku M, Fujieda M, Suganuma N, Hatakenaka Y, et al. Development of a parent-reported screening tool for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID): initial validation and prevalence in 4-7-year-old Japanese children. Appetite. 2022;168:105735.

Gonçalves S, Vieira AI, Machado BC, Costa R, Pinheiro J, Conceiçao E. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder symptoms in children: associations with child and family variables. Children’s Health Care. 2019;48:301–13.

Fisher MM, Rosen DS, Ornstein RM, Mammel KA, Katzman DK, Rome ES, et al. Characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in children and adolescents: a new disorder in DSM-5. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:49–52.

Katzman DK, Spettigue W, Agostino H, Couturier J, Dominic A, Findlay SM, et al. Incidence and age-and sex-specific differences in the clinical presentation of children and adolescents with avoidant restrictive food intake disorder. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:e213861–213861.

Farag F, Sims A, Strudwick K, Carrasco J, Waters A, Ford V, et al. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder and autism spectrum disorder: clinical implications for assessment and management. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2022;64:176–82.

Kambanis PE, Harshman SG, Kuhnle MC, Kahn DL, Dreier MJ, Hauser K, et al. Differential comorbidity profiles in avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder and anorexia nervosa: does age play a role? Int J Eat Disord. 2022;55:1397–403.

Fisher M, Gonzalez M, Malizio J. Eating disorders in adolescents: how does the DSM-5 change the diagnosis? Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2015;27:437–41.

Williams KE, Hendy HM, Field DG, Belousov Y, Riegel K, Harclerode W. Implications of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) on children with feeding problems. Children’s Health Care. 2015;44:307–21.

Krom H, van der Sluijs Veer L, van Zundert S, Otten M, Benninga M, Haverman L, et al. Health related quality of life of infants and children with avoidant restrictive food intake disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2019;52:410–8.

Chen Y-L, Chen WJ, Lin K-C, Shen L-J, Gau SS-F. Prevalence of DSM-5 mental disorders in a nationally representative sample of children in Taiwan: methodology and main findings. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e15.

Iron-Segev S, Best D, Stein D. Symptoms of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) in the orthodox and secular jewish communities in Israel. J Relig Health. 2023;62:268–86.

Schmidt R, Vogel M, Hiemisch A, Kiess W, Hilbert A. Pathological and non-pathological variants of restrictive eating behaviors in middle childhood: a latent class analysis. Appetite. 2018;127:257–65.

Bourne L, Bryant-Waugh R, Cook J, Mandy W. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: a systematic scoping review of the current literature. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112961.

Sysko R, Glasofer DR, Hildebrandt T, Klimek P, Mitchell JE, Berg KC, et al. The Eating Disorder Assessment for DSM-5 (EDA‐5): development and validation of a structured interview for feeding and eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48:452–63.

First MB, Williams JBW, Karg RS, Spitzer RL. Structured clinical interview for DSM-5 disorders–research version (SCID-5-RV). Arlington: American Psychiatric Assocation; 2014.

Bryant-Waugh R, Micali N, Cooke L, Lawson EA, Eddy KT, Thomas JJ. Development of the Pica, ARFID, and Rumination Disorder Interview, a multi‐informant, semi‐structured interview of feeding disorders across the lifespan: a pilot study for ages 10–22. Int J Eat Disord. 2019;52:378–87.

Bryant-Waugh R, Stern CM, Dreier MJ, Micali N, Cooke LJ, Kuhnle MC, et al. Preliminary validation of the pica, ARFID and rumination disorder interview ARFID questionnaire (PARDI-AR-Q). J Eat Disord. 2022;10:1–10.

Kurz S, Van Dyck Z, Dremmel D, Munsch S, Hilbert A. Early-onset restrictive eating disturbances in primary school boys and girls. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24:779–85.

Zickgraf HF, Ellis JM. Initial validation of the Nine Item Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake disorder screen (NIAS): a measure of three restrictive eating patterns. Appetite. 2018;123:32–42.

Austin A, De Silva U, Ilesanmi C, Likitabhorn T, Miller I, da Fialho M. International consensus on patient-centred outcomes in eating disorders. Lancet Psychiatry. 2023;10:966–73.

Burton Murray H, Dreier MJ, Zickgraf HF, Becker KR, Breithaupt L, Eddy KT, et al. Validation of the nine item ARFID screen (NIAS) subscales for distinguishing ARFID presentations and screening for ARFID. Int J Eat Disord. 2021;54:1782–92.

Billman Miller MG, Zickgraf HF, Murray HB, Essayli JH, Lane-Loney SE. Validation of the youth‐nine item avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder screen. Eur Eat Disorders Rev. 2024;32:20–31.

Presseller EK, Cooper GE, Thornton LM, Birgegard A, Abbaspour A, Bulik CM et al. Assessing avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder symptoms using the Nine Item ARFID screen in > 9,000 Swedish adults with and without eating disorders. MedRxiv 2024:2024–5.

Medina-Tepal KA, Vazquez‐Arevalo R, Trujillo‐ChiVacuán EM, Zickgraf HF, Mancilla‐Díaz JM. Cross‐cultural adaptation and validation of the Nine Item ARFID screen (NIAS) in Mexican youths. International Journal of Eating Disorders; 2022.

Ziółkowska B, Ocalewski J, Zickgraf H, Brytek-Matera A. The Polish Version of the Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Questionnaire—Parents Report (ARFID-Q-PR) and the nine items Avoidant/Restrictive food intake disorder screen—parents report (NIAS-PR). Maternal Perspective Nutrients. 2022;14:3175.

He J, Zickgraf HF, Ellis JM, Lin Z, Fan X. Chinese version of the nine item ARFID screen: psychometric properties and cross-cultural measurement invariance. Assessment. 2021;28:537–50.

Fekih-Romdhane F, Hallit R, Malaeb D, Sakr F, Dabbous M, Sawma T, et al. Psychometric properties of an arabic translation of the Nine Item Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Screen (NIAS) in a community sample of adults. J Eat Disord. 2023;11:1–10.

Schmidt U, Adan R, Böhm I, Campbell IC, Dingemans A, Ehrlich S, et al. Eating disorders: the big issue. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:313–5.

Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Eating disorder examination questionnaire. Cogn Behav Therapy Eat Disorders. 2008;309:313.

Gideon N, Hawkes N, Mond J, Saunders R, Tchanturia K, Serpell L. Development and psychometric validation of the EDE-QS, a 12 item short form of the eating disorder examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q). PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0152744.

Yucel B, Polat A, Ikiz T, Dusgor BP, Elif Yavuz A, Sertel Berk O. The Turkish version of the eating disorder examination questionnaire: reliability and validity in adolescents. Eur Eat Disorders Rev. 2011;19:509–11.

Chorpita BF, Yim L, Moffitt C, Umemoto LA, Francis SE. Assessment of symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety and depression in children: a revised child anxiety and depression scale. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38:835–55.

Gormez V, Kılınçaslan A, Orengul AC, Ebesutani C, Kaya I, Ceri V, et al. Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the revised child anxiety and Depression Scale–Child Version in a clinical sample. Psychiatry Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;27:84–92.

Hunot C, Fildes A, Croker H, Llewellyn CH, Wardle J, Beeken RJ. Appetitive traits and relationships with BMI in adults: development of the adult eating Behaviour Questionnaire. Appetite. 2016;105:356–63.

Mallan KM, Fildes A, de la Piedad Garcia X, Drzezdzon J, Sampson M, Llewellyn C. Appetitive traits associated with higher and lower body mass index: evaluating the validity of the adult eating behaviour questionnaire in an Australian sample. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2017;14:1–8.

Yardımcı H, Ersoy N, Çin NNA. Validity and reliability of Turkish version of the adult eating Behaviour Questionnaire for adult participants. Public Health Nutr. 2023;26:2218–25.

Hunot-Alexander C, Beeken RJ, Goodman W, Fildes A, Croker H, Llewellyn C, et al. Confirmation of the factor structure and reliability of the ‘adult eating behavior questionnaire’in an adolescent sample. Front Psychol. 2019;10:456905.

Guzek D, Skolmowska D, Głąbska D. Appetitive traits in a population-based study of Polish adolescents within the place-19 study: validation of the adult eating behavior questionnaire. Nutrients. 2020;12:3889.

Neyzi O, Furman A, Bundak R, Gunoz H, Darendeliler F, Bas F. Growth references for Turkish children aged 6 to 18 years. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:1635–41.

Team J. JASP (version 0.14. 1)[computer software]. 2020.

Team RC. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. ; 2021. (No Title).

Revelle W, Psych. Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research.[R package]. Https://Cran r-Project Org/Package = Psych [Right Angle Bracket]; 2019. Retrieved from [Left Angle Bracket].

Rosseel Y, Jorgensen TD, Oberski D, Byrnes J, Vanbrabant L, Savalei V et al. lavaan: Latent variable analysis.[R package] 2018.

Epskamp S, Epskamp MS, MplusAutomation S, Package. ‘semPlot.’ Recuperado de Https://Cran r-Project Org/Web/Packages/SemPlot/SemPlot Pdf 2017.

Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford; 2015.

Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol Res Online. 2003;8:23–74.

Keith TZ. Multiple regression and beyond: an introduction to multiple regression and structural equation modeling. Routledge; 2019.

Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford; 2015.

Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics 5th ed. 2018.

Zacks S. Introduction to reliability analysis: probability models and statistical methods. Springer Science & Business Media; 2012.

Fekih-Romdhane F, Hallit R, Malaeb D, Sakr F, Dabbous M, Sawma T, et al. Psychometric properties of an arabic translation of the Nine Item Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Screen (NIAS) in a community sample of adults. J Eat Disord. 2023;11:143.

Ellis JM, Galloway AT, Webb RM, Martz DM. Measuring adult picky eating: the development of a multidimensional self-report instrument. Psychol Assess. 2017;29:955.

Tharner A, Jansen PW, Kiefte-de Jong JC, Moll HA, van der Ende J, Jaddoe VWV, et al. Toward an operative diagnosis of fussy/picky eating: a latent profile approach in a population-based cohort. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2014;11:1–11.

Zickgraf HF, Murray HB, Kratz HE, Franklin ME. Characteristics of outpatients diagnosed with the selective/neophobic presentation of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2019;52:367–77.

He J, Sun S, Zickgraf HF, Ellis JM, Fan X. Assessing appetitive traits among Chinese young adults using the adult eating Behavior Questionnaire: factor structure, gender invariance and latent mean differences, and associations with BMI. Assessment. 2021;28:877–89.

Zickgraf HF, Franklin ME, Rozin P. Adult picky eaters with symptoms of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: comparable distress and comorbidity but different eating behaviors compared to those with disordered eating symptoms. J Eat Disord. 2016;4:1–11.

Zickgraf HF, Lane-Loney S, Essayli JH, Ornstein RM. Further support for diagnostically meaningful ARFID symptom presentations in an adolescent medicine partial hospitalization program. Int J Eat Disord. 2019;52:402–9.

Thomas JJ, Lawson EA, Micali N, Misra M, Deckersbach T, Eddy KT. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: a three-dimensional model of neurobiology with implications for etiology and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19:1–9.

Billman Miller MG, Zickgraf HF, Murray HB, Essayli JH, Lane-Loney SE. Validation of the youth‐nine item avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder screen. European Eating Disorders Review; 2023.

Kambanis PE, Kuhnle MC, Wons OB, Jo JH, Keshishian AC, Hauser K, et al. Prevalence and correlates of psychiatric comorbidities in children and adolescents with full and subthreshold avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53:256–65.

Bryson AE, Scipioni AM, Ornstein RM. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: categorization of subtypes and longitudinal outcomes after day hospitalization. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60:S45–6.

Lieberman M, Houser ME, Voyer A, Grady S, Katzman DK. Children with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder and anorexia nervosa in a tertiary care pediatric eating disorder program: a comparative study. Int J Eat Disord. 2019;52:239–45.

Duncombe Lowe K, Barnes TL, Martell C, Keery H, Eckhardt S, Peterson CB, et al. Youth with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: examining differences by age, weight status, and symptom duration. Nutrients. 2019;11:1955.

Thomas JJ, Eddy KT. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: children, adolescents, and adults. Cambridge University Press; 2018.

Zickgraf HF, Richard E, Zucker NL, Wallace GL. Rigidity and sensory sensitivity: independent contributions to selective eating in children, adolescents, and young adults. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2022;51:675–87.

Fernandez C, McCaffery H, Miller AL, Kaciroti N, Lumeng JC, Pesch MH. Trajectories of picky eating in low-income US children. Pediatrics 2020;145.

Sherry B, Jefferds ME, Grummer-Strawn LM. Accuracy of adolescent self-report of height and weight in assessing overweight status: a literature review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:1154–61.

Acknowledgements

We thank the adolescent who participated as volunteers in this study.

Funding

There are no funders to report for this submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MK: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; software; supervision; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. HÖ: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; software; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. UD: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; validation; visualization; writing – original draft. HFZ: Conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. MHT: Conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics statement

Ethics committee approval was obtained for the study from the Social Sciences University of Ankara Institutional Ethics Committee of Social Sciences and Humanities Research and Publication (Date / No: 03.01.2023 / 62667).

Consent for publication

The authors consent for this manuscript to be published. There are no other parties involved in the decision to publish.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it.The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaşak, M., Öğütlü, H., Doğan, U. et al. Psychometric properties of the nine-item avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder screen (NIAS) in Turkish adolescents. J Eat Disord 12, 105 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-024-01066-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-024-01066-0