Abstract

Understanding the crop management practices of millet agriculture is pivotal for comprehending the development of Chinese civilization. Recent studies have indicated that organic manuring plays a crucial role in ensuring sustainable millet cultivation on the Loess Plateau. However, uncertainties still exist regarding how manuring practices impact the δ15N values of C4 millets compared to C3 cereals. Furthermore, inadequate information on crop δ15N at archaeological sites has led to controversial interpretations of animal and human diets. In this study, we present new findings from an experimental archaeological research conducted in actual loess farmland in China to explore the potential range of variability in grain δ15N values of millets. Our results demonstrate that animal manure significantly increases Setaria and Panicum grain δ15N values, ranging from 2.7 to 9.3‰. Considering trophic enrichment effects on nitrogen isotopes, humans consuming manured millets may yield values ranging from 5.7 to 12.3‰, suggesting alternative explanations for high δ15N values other than animal protein consumption. Opposite to the general hypothesis, the grain δ15N values are systematically lower than those of leaves. The difference between the values of Setaria and Panicum and the process of manure influencing the grain δ15N values are also discussed. Our study provides novel insights into the nitrogen stable isotopic indicator of millet manuring and will serve to set reconstructions of past manuring and diet practices in northern China on a firmer foundation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Foxtail millet (Setaria italica) and broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum) are domesticated crops native to prehistoric northern China [1,2,3,4]. Millet agriculture has been practiced for over 8000 years, gradually replacing hunting and gathering activities as the dominant economic activity in northern China around 6000 years ago [5, 6]. Archaeobotanical finds have revealed that millets were also cultivated in southern China, Southeast and Northeast Asia, and were common in Europe from the 2nd millennium BC along with the trans-Eurasian exchanges [7]. The spread of millet brought new species resources and even facilitated the agriculturalization of the introduced areas [8]. Therefore, studying millet agriculture provides an important approach for understanding the development of early cultures and the formation of ancient Chinese civilization [9,10,11], as well as prehistoric cultural interactions across Eurasia.

The rapid loss of organic matter and low nitrogen content in loess soils in northern China have remained significant constraints on the growth of millets [12,13,14]. The application of animal manure enhances nutrient availability for plants, and it has been viewed as an important driving factor for the expansion of millet agriculture and early cultures on the Loess Plateau of China [15, 16].

Previous field experiments conducted in western Eurasia reveal that nitrogen stable isotopes in plants serve as an essential indicator of manuring practice on C3 crops (e.g., wheat, barley), with manuring resulting in higher δ15N values in these crops [17,18,19,20,21,22,22]. However, the impact on millets of East Asia remains obscure. Although recent studies on millets have shown that manuring increases millet δ15N values (Table 1), none of them was conducted within the loess region of China [16, 23,24,25], and the differences in growing conditions (e.g., soil type, precipitation, temperature) limit their applicability to assess archaeological remains.

Due to the diverse subsistence economy on the Loess Plateau of China [26,27,28], ancient humans had access to variable types of animal manure, which has received little attention, despite their significant differences in the impact on crop yields [29, 30]. For people whose livelihood primarily relies on millet agriculture, pig dung is an easily accessible organic manure due to the close association between domestic pigs and millet farming [15, 24]. The higher δ15N values observed in charred millet grains have often been attributed to fertilization with pig manure [15, 16]. However, there is still a lack of experimental data to verify the impact of pig manure on millets. Pastoralism is characterized by cattle and sheep rearing [26, 28], resulting in the availability of their dung as animal manure for ancient people in pastoral areas when they carried out millet cultivation. Chicken is one of the “six livestock”, and chicken manure is also a high-quality fertilizer in modern agriculture [31]. Therefore, it holds great significance to explore how different animal manure influence the millet δ15N values and whether there is any difference among them, which will contribute to deeper insights into past crop management practices, utilization of animal resources, and subsistence patterns of ancient people across diverse regions.

Furthermore, there has been limited discussion on Panicum compared to Setaria, along with an incomplete understanding regarding the entire process through which manuring influences millet grain δ15N values, including the fermentation of animal manure and the δ15N offset between different growing stages. These gaps hinder our comprehension of the mechanisms underlying manuring effects and impede the establishment of isotopic criteria for assessing manuring practices.

Regarding palaeodiet, stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis has played a pivotal role in reconstructing past diets and revealing social complexity in northern China (e.g., [15, 35,36,37,38]). On the one hand, stable carbon isotopes can provide an overview on the consumption of C3 versus C4 food in terrestrial foodwebs. Foxtail and broomcorn millets are both typical C4 plants with higher δ13C values than C3 plants. The isotopic characteristics would be transferred through the foodwebs with isotopic fractionation. Prehistoric humans and domesticated animals exclusively consuming C3 or C4 plants are conventionally thought to exhibit δ13C values around − 20.0‰ or − 6.0‰ respectively [26]. On the other hand, nitrogen isotopes often provide an estimate on the trophic levels for organisms. While the δ15N values of plants are transferred up the food chain and recorded in the isotopic signatures of herbivores and human diets [19, 39, 40], plant δ15N values are critical for reliable interpretation of animal and human remains. However, the lack of available information on plant δ15N from archaeological sites results in assumptions based on generalized plant values, despite the considerable variation observed in plant δ15N values [41,42,43,44]. This challenges conventional interpretation of δ15N values of ancient animals and humans and highlights the urgent need for data on the δ15N variation of millets.

This paper aims to explore the potential range of variability in grain δ15N values, specifically focusing on manured millets, in order to set reconstructions of past manuring and diet practices in northern China on a firmer foundation. In this study, we employed an experimental archaeological approach by cultivating millets in actual loess farmland in the Guanzhong Basin, the core area of prehistoric millet agriculture in China. Various treatments were applied, including different types and levels of manure. Additionally, we considered the fermentation of animal manure, the δ15N offset between the heading and mature period of soil and different parts of foxtail and broomcorn millet. The heading period serves as an intermediate phase during crop growth. The purpose of sampling at this stage was to systematically study the changes of stable nitrogen isotopes within the farmland ecosystem during the growth of crops after fertilization. We expect the exploration of the complete process of manuring affecting crop stable nitrogen isotopes can provide a theoretical basis and reference for follow-up studies. Overall, these data can be used to assess past manuring and its impact on human bone collagen values, enhancing the accuracy of manuring and dietary reconstructions.

Materials and methods

Experimental materials

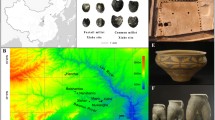

In this study, foxtail and broomcorn millet were cultivated separately in two large experimental areas located in the Jufeng Agricultural Specialized Cooperative in Lintong (临潼) District, Xi'an City, Shaanxi Province. A standard treatment was implemented in each experiment area to ensure similar soil fertility. The seeds used for planting were marketed as breeding grains to guarantee proper germination.

As stated in the introduction, manure from four common types of domestic animals (pig, cattle, sheep, chicken) was selected for this study. In accordance with the standard application rate of organic fertilizer in modern agriculture (15 t/ha) [45], two application rates of 9 t/ha and 21 t/ha were also set to form three manuring levels of low, medium and high. Due to the prevalent use of chemical fertilizers in modern agriculture, two common types of chemical fertilizers—urea and compound fertilizers, and an unmanured treatment were selected as controls. The compound fertilizers used here had N, P2O5, and K20 contents exceeding 45% and belonged to the potassium sulfate-type category. Urea was applied at a rate of 0.3 t/ha while compound fertilizer was 0.675 t/ha according to the recommended dosage on the package. Three replications were set for each treatment to minimize experimental errors.

Experimental design

The four types of animal manure were stacked in close proximity to each other adjacent to the experimental area. They underwent natural fermentation from May 16 to July 13, 2022, aiming to achieve complete maturity as much as possible. No strains of bacteria or other substances were added artificially to minimize disturbance.

Foxtail and broomcorn millet were separately cultivated within a large experimental area on July 14, 2022. Panicum was harvested on September 29, while Setaria was on October 13. The layout of a single experimental area is outlined in Fig. 1. Figure 2 shows the millets grown on actual farmland in Xi'an, Shaanxi Province, China, in 2022. The grains were mechanically sown while the fertilizers were manually spread after careful weighing.

The millet grown in actual farmland in Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, China, in 2022 (see Fig. 1 for details of plots involved in this study). The photos show fermentation of animal manure (upper left), the experimental area (Setaria, upper middle; Panicum, upper right), foxtail millet (lower left), and broomcorn millet (lower middle) close to harvest time. The lower right shows the harvest of broomcorn millet

Pig manure (Z), cattle manure (N), sheep manure (Y), and chicken manure (J) were applied at low (L, 9 t/ha), medium (M, 15 t/ha), and high (H, 21 t/ha) levels, with unmanured (CK), urea (U), and compound fertilizer (CF) serving as control treatments.

In total, there were fifteen treatments applied for Setaria and Panicum separately, with each plot of treatment equally divided into three subplots on behalf of three replications. Each subplot is approximately 14 m2. The total experimental area is about 1332 m2, with isolation zones set up. Other planting conditions, such as irrigation regime, temperature, and soil type, were identical except for the aforementioned manuring strategies. Fertilizers were applied once as bottom fertilizers, without subsequent follow-up applications.

Sampling strategies

Three sampling sessions were conducted during the experiment, as shown in Table 2.

Before spreading the manure, soil (n = 2), seeds for sowing (n = 2), animal manure before and after fermentation (n = 8), and chemical fertilizers (n = 2) were sampled.

The second sampling was performed when crops were basically in the heading stage, while Setaria was still in the booting period due to its inconsistent growth progress with Panicum, which means there was no access to Setaria grains at this stage. Considering that the sampling during the heading stage is aimed at understanding the entire process of grain nitrogen isotope variation influenced by fertilization, we collected soil and plant samples at different stages, with a focus on soil and leaf data, which we believe are sufficient for achieving our objectives. The formation of testable grains occurs later in the growth cycle and varies among different crops. Therefore, grain data in the heading period is not essential. Instead, mature grain data constitutes the main and crucial part of our experiment. As a result, no additional sampling was conducted during the heading stage of Setaria. Plants and soil were sampled from each subplot.

The harvested material was left to dry indoors before being separated into grains and leaves. Subsequently, the grains were dehusked and cleaned. A total of 508 samples were collected for testing, including nine fertilizer samples (the urea sample could not be collected due to improper storage), 182 soil samples, 180 leaf samples, and 137 grain samples.

Elemental content and isotope analyses

Plant samples were pretreated according to the method described by Styring et al. [46]. The procedure involved the following steps: (1) Approximately 1 g of healthy leaves and grains were carefully selected from each sample and thoroughly rinsed with deionized water until all impurities adhering to the grains and leaf surfaces were removed. The cleaned leaves and grains were then transferred into small beakers. (2) The beakers containing Setaria and Panicum leaves and grains were placed in an oven at 60 °C for approximately 48 h to ensure complete drying until a constant weight was achieved. (3) The dried leaf and grain samples were finely ground into a homogeneous powder using an agate mortar/pestle and then packed into small sample vials using weighing paper. (4) Tin containers were used to weigh 3 to 5 mg of each sample, which was prepared for subsequent analysis.

Soil samples were pretreated using the method of Liu et al. [47], which included the following steps. (1) 5 g of soil from each sample was extracted, fully dried in an oven at 60 °C, and subsequently milled until it could pass through a sieve with a mesh size of 200 mesh. (2) The milled soil samples were soaked in a dilute hydrochloric acid solution (0.5 mol/L) for at least 24 h, followed by washing with deionized water until neutral pH was reached. After drying again, they underwent further milling to obtain powdered form. (3) Approximately 20 mg of soil powder was weighed out and placed into tin capsules for measurement.

Animal manure pretreatment referred to the method described by Codron et al. [48]. Firstly, 5 g of fecal samples were carefully selected and mechanically cleaned before being placed into small beakers. Subsequently, the beakers were transferred to a 50 °C oven for drying. Afterward, the dried samples were ground into powder and approximately 3–5 mg of sample powder was packed into a tin capsule for analysis using high-temperature dry combustion to measure total N and 15N levels. Chemical fertilizers were directly ground and packed as well.

Sample testing was performed at the Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, using an IsoPrime 100 IRMS (Elementar, UK) coupled with an ElementarVario (Elementar, UK) with nitrogen stable isotope ratios expressed as δ per mil (‰) relative to the internationally defined standards for nitrogen (Ambient Inhalable Reservoir, AIR). The standards of the tests were IAEA-600 and IAEA-N-2 calibrated nitrogen cylinder gas with Te measurement errors less than ± 0.2‰.

Results

All the data of 508 samples, including fertilizers, soils, leaves and grains covering the three pre-sowing, heading, and maturity periods, are shown in Fig. 3 and Table 3. Each fertilizer sample was tested twice to obtain its δ15N values to minimize errors.

The nitrogen isotope values of 508 samples in this experiment. (B and A under the fertilizer box refer to the samples before and after fermentation. L, M, and H correspond to low, medium, and high manuring levels, respectively, while CK, U, and CF correspond to unmanured, urea, and compound fertilizer treatments, respectively. The horizontal dashed line in the soil box indicates the original soil δ15N value before being manured (5.2 ‰ for Setaria and 7.0‰ for Panicum), and the horizontal dashed line in the grain box indicates the δ15N value of the seeds used for sowing (0.4‰ for Setaria and 2.3‰ for Panicum.). Each of the horizontal dashed lines and points in the figure corresponds to the data of one sample.)

Variation in grain δ 15N values

Compared with soil and leaves, millet grains are a key plant part identifiable to species and widely preserved in charred form. As a result, grain δ15N values receive more attention from us.

The results for grains are shown in Fig. 3 and Table 3. The δ15N values of original seeds for sowing were 0.4‰ for Setaria and 2.3‰ for Panicum.

When treated with animal manure, the mature grain δ15N values for Setaria ranged from 2.7 to 4.4‰ (mean 3.4 ± 0.3‰, n = 36). For Panicum, the grain δ15N values in the heading period ranged from 0.9 to 5.9‰ (n = 36), while in the mature period, they ranged from 4.4 to 9.3‰ (mean 6.1 ± 1.2‰, n = 36).

Variations in δ15N values of mature grains after fertilization with different animal manure and manuring levels must also be expected. Specifically, the δ15N values of Panicum grains treated with cattle manure ranged from 5.2 to 9.3‰ (mean 7.2 ± 1.1‰, n = 9), while Setaria grains treated with sheep manure exhibited a range of 2.7‰ to 3.3‰ (mean 3.1 ± 0.2‰, n = 9). Among the four types of animal manure, the NL treated Panicum grains had the highest value, whereas Setaria grains on YM plots yielded the lowest one. Regarding different levels of animal manure application, grains from the low level of pig and cattle manure(ZL and NL) were associated with the highest δ15N values than the medium and high level, whereas the high level of sheep and chicken manure (YH and JH) showed the highest values than the low and medium level. However, it is worth noting that there are no clear distinctions among the four types of animal manure due to their largely overlapping ranges. The results also showed no lower or higher δ15N values with higher manuring levels.

For grains on the control plots, the δ15N values of mature grain ranged from 1.7 to 3.9‰ for Setaria and 2.9 to 5.8‰ for Panicum. And the grain values under urea treatment were the lowest regardless of Setaria or Panicum.

Data on fertilizers

Table 4 summarizes the results for four kinds of animal manure before and after fermentation.

The δ15N values of animal manure ranged from 2.9 to 9.3‰ (n = 4) before fermentation and 7.2 to 9.5‰ (n = 4) after fermentation, while the TN (total nitrogen content) values of animal manure ranged from 1.66 to 3.08% before fermentation and 1.56% to 2.27% after fermentation. Additionally, compound fertilizer exhibited the lowest δ15N values (mean − 2.0 ± 0.1‰, n = 2) and the highest TN values (18.4%).

Variation in soil δ 15N values

As shown in Fig. 3 and Table 3, the original soil δ15N values before manuring were 5.2 ‰ for Setaria and 7.0‰ for Panicum.

In the Setaria area, the soil δ15N values ranged from 4.4 to 7.0‰ (n = 45) in the heading period and from 4.7 to 7.1‰ (n = 45) in the mature period. Similarly, in the Panicum area, the values ranged from 4.2 to 7.0‰ (n = 45) in the heading period and from 3.8 to 8.1‰ (n = 45) in the mature period.

Variations in soil δ15N values after fertilization with different types of animal manure and manuring levels are also presented in Fig. 3 and Table 3. It should be noted that differences in soil δ15N values among different treatments generally do not align with those observed in grain values. For instance, the highest manured soil δ15N values occur on YM plots whereas the lowest values are on ZH plots in the mature period of Setaria. Furthermore, the interval widths of soil δ15N variation under cattle manure treatment were 0.9‰ (for Setaria) and 2.1‰ (for Panicum), which were relatively low compared with other manure types. The widths of soil δ15N variation under pig manure treatment were 2.1‰ (for Setaria) and 3.4‰ (for Panicum), both reaching higher levels.

Variation in leaf δ 15N values

The leaf data are shown in Fig. 3 and Table 3. In the heading period of Setaria, the leaf δ15N values ranged from 0.6 to 8.2‰ (n = 45) while in the mature period, a wider range of values was observed, from − 0.2 to 8.2‰ (n = 45). Similarly, for Panicum, the leaf δ15N values were − 0.1 to 7.2‰ (n = 45) in the heading period and 1.3 to 8.3‰ (n = 45) in the mature period.

For leaves treated with different types of animal manure and manuring levels, the values of mature leaves range from 3.7 to 8.2‰ for Setaria and from 1.3 to 8.3‰ for Panicum, respectively, both of which are wider than those of grains. It might be noteworthy that the leaf under sheep manure treatment exhibited the minimum δ15N values of 4.6‰ (for Setaria) and 5.4‰ (for Panicum), both lower than the minimum values observed with other types of manure. Moreover, these values above also displayed a narrower range of variation, specifically 3.3‰ (for Setaria) and 1.8‰ (for Panicum), which were also the lowest among the four types. Mature leaves on JH and NM plots were associated with highest δ15N values on average than those at the other two manuring levels, showing an overall irregular variation pattern.

Discussion

Grain δ 15N values and implications for past manuring and diets

Previous modern experiments conducted in western Eurasia have demonstrated that nitrogen stable isotope constitutes an effective indicator of past manuring for C3 crops [17,18,19]. While for C4 millets, the data from the farmland experiment in China reported here suggest that animal manure application also significantly influenced the Setaria and Panicum grain values. Compared to the seeds for sowing, manuring resulted in an increase of 2.3–4.0‰ and 2.1–7.0‰ in grain δ15N values of Setaria and Panicum respectively. From the data in Fig. 4 and Table 3, the variation ranges of grain δ15N values are largely overlapping and cannot be clearly distinguished when they are treated with different types of animal manure or manuring levels. Furthermore, it is always unlikely to ascertain precise information regarding both the amount and type of animal manure used by prehistoric farmers due to the diversity of animal husbandry on the Loess Plateau. Thus, the overall scope of grain δ15N values grown on manured plots ranging from 2.7 to 9.3‰ may serve as a more practical reference for evaluating past manuring practices. It should be noted that a recent manuring experiment on millet in the greenhouse at the University of Oxford found manured millets with high δ15N values (8.2–18.2‰, mean 13.1 ± 2.3‰, n = 43), surpassing those typically observed among modern millets [24]. The disparity could potentially be attributed to differences arising from contrasting growth environments compared to Chinese millets cultivated on actual farmland.

The impact of manure on grain δ15N values comes with implications for reconstructing past dietary practices. The trophic enrichment of nitrogen isotope ratio is conventionally estimated to be 3–5‰ [44], based on what they eat [49]. For herbivores, including humans with plant-based diets, the δ15N values deriving from the analysis of bone collagen would range from 3 to 7‰, while for diets primarily consisting of animal products, the values would be higher than 9‰. Values for a mixed diet would lie between 7 and 9‰ [50, 51].

To achieve more precise identification of C4 consumption in humans and animals, it is necessary to combine carbon and nitrogen. Table 5 presents the δ15N and the δ13C data collected from several archaeological sites in northern China. The δ13C values of human bone collagen were predominantly around − 6.0‰, indicating a diet dominated by millet-related resources when combined with archaeobotanical results. Values of associated domestic animals are critical for the accurate interpretation of human values. As shown in Table 5, pig δ13C values are basically equal to human values, suggesting their similar millet-based diets and pigs are also possible resource of C4 food for humans. Although the δ15N values of humans are slightly higher than those of pigs, the difference is far from the trophic enrichment of 3‰. The results suggest that plant-based C4 foods were staple foods for people, instead of animal protein from pigs.

Human δ15N values have traditionally been interpreted as indicative of a diet primarily based on animal protein when exceeding 9‰ (Table 5). However, our study reveals that manured millet grain δ15N values can range from 2.7 to 9.3‰. If we assume that humans were the primary consumers of millet grains and with trophic enrichment of 3‰, the values of humans primarily consuming grains would be expected to reach 5.7–12.3‰. Thus, fairly high values of ancient humans could result from millet consumption, rather than the attribution of animal protein. Since the middle and late Yangshao period, the prosperity of Yangshao culture was accompanied by the intensification and expansion of millet agriculture [15], whereas the unbalanced development of agriculture across different temporal and spatial contexts offers diverse interpretations for the δ15N values of ancient people. For instance, current evidence suggests that animal husbandry gradually became the predominant livelihood in central and southern Inner Mongolia around 3000 BP [52]. For subsequent sites such as the Nalintaohai [53], Fuluta [54], Xindianzi [55] cemetery, the high human δ15N values may be attributed to the consumption of animal protein derived from meat or dairy products from domesticated animals. However, the Guanzhong region underwent a transition towards agricultural production dominance around 6000BP, characterized by the flourishing development of dryland agriculture represented by millets [56, 57]. Consequently, the high δ15N values observed in human remains from sites since then, such as the Jianyu [58], Guangming, Jichang and Guandao cemeteries [59], are more plausibly explained by the consumption of manured millets rather than animal protein. Similar considerations are also applicable to regions like Henan and Shanxi which transitioned into agricultural societies since the middle and late Neolithic period [60, 61], exemplified by sites like Neiyangyuan [62] and Baligang site [60].

Certain trends inferred from comparisons of isotope data also warrant reevaluation. Taking the Qingliangsi site in Shanxi as an example, the human δ15N values increased from 8.1 ± 1.1‰ (n = 13) during the Yangshao period to 8.8 ± 0.9‰ (n = 14) during the Longshan period. The elevation likely reflects continues development of agriculture since the Yangshao period, with manuring practices contributing to higher crop δ15N values and subsequently affecting human δ15N values. The previous interpretation that attributed this general rise solely to increased meat consumption compared to the Yangshao period may be problematic, particularly during the Longshan preiod characterized by evident social differentiation and stratification.

According to zooarchaeological evidence, animal husbandry was widespread and intensified since the middle and late Neolithic in northern China [63, 64], suggesting it was not implausible to collect more than 0.9 kg/m2 (9 t/ha) of animal manure each year. The discussion above also indicates that it is crucial to establish an isotope foodweb including plants and animals when scientifically interpreting isotopic data from humans [65]. Moreover, if we assume that pigs primarily consumed millet by-products, the difference in δ15N values between domestic pigs and humans may be result from the discrepancy in δ15N values between millet grains and by-products, though their relationship remains unclear compared to C3 cereals and requires more modern experiments to provide evidence.

Furthermore, Setaria and Panicum are both C4 plants, but they follow two different biochemical photosynthetic types [71]. The δ15N comparison between Setaria and Panicum has been rarely addressed. Our results show higher δ15N values of Panicum (4.4–9.3‰, mean 6.1 ± 1.2‰, n = 36) than Setaria (2.7–4.4‰, mean 3.4 ± 0.3‰, n = 36) and the response of Panicum grain δ15N variation is more pronounced than that of Setaria, which probably suggests the potential of stable nitrogen isotope analysis of millets for distinguishing Setaria and Panicum at the species level. Moreover, the discrepancy may also influence the accuracy of dietary reconstruction, as human consumers of Panicum grains may tend to exhibit higher δ15N values, implying the importance to combine with archaeobotanical results.

The relationship in δ 15N values between grain and leaf

In accordance with previous studies on modern C3 crops, the grain δ15N values are higher than those of other parts (e.g., leave, straw, rachis) [17,18,19]. For C4 millets, leaf δ15N values are generally thought to be lower than those observed in grain. This relative relationship has led to the interpretation that pigs were fed millet leaves or other byproducts and grains were mostly consumed by humans at prehistoric sites, which explains the slightly higher human δ15N values than those of pigs [15, 16, 27]. However, the results from this experiment suggest that the δ15N values in grain tend to be lower than those in leaf, with an average difference of approximately 0.9‰ (Fig. 5). This finding holds significant implications for palaeodietary work, where the values of grains consumed by humans are often assumed to be higher. Previous interpretations for the mean δ15N offset between archaeological grains, domestic animals and humans based on this hypothesis [72, 73] may require reconsideration.

The response of grain δ 15N values to different fertilizers and manuring levels

Previous studies have primarily focused on investigating the impact of a single type of animal manure on δ15N values in modern crops (Table 1). In this study, we further discussed the implications of manuring with different types of animal manure on millet grain values. Figures 4 and 6 show that manure type significantly influenced millet grain δ15N values. For example, mature grain δ15N values are the highest on average after fertilization with cattle manure. Conversely, grains fertilized with pig and chicken manure exhibited lower but comparable levels to each other, showing no significant difference. Notably, the minimum values of grains under cattle manure treatment were 3.5‰ (for Setaria) and 5.2‰ (for Panicum), while the maximum values were 4.0‰ (for Setaria) and 9.3‰ (for Panicum). Compared to other types of manure, these values are all relatively high, suggesting that grains treated with cattle manure may have a greater potential for achieving higher δ15N values. On the contrary, both minimum and maximum grain δ15N values under chicken manure treatment were comparatively lower than those associated with other types of manures used in this study, potentially indicating a weaker ability of chicken manure to increase grain δ15N levels.

The variation probably results from factors such as the isotopic composition and the mineralization rate of the fertilizers [74,75,76,77], implying the potential to differentiate the manuring effect of various types of manure. However, as shown in Figs. 4 and 6, the differences in grain δ15N values are inconsistent within different species and periods, and whether the physiological characteristics of crops or other factors contributed to this still need to be further explored.

Different crops have been cultivated with continuous fertilizers applied in the experimental area for many years. The grain δ15N values on CK, CF and manured plots did not differ significantly (Fig. 3), probably due to the farmland history of cultivation and fertilization. The grains grown on urea plots displayed lower values, consistent with the depletion of 15N associated with urea [78].

Furthermore, although three manuring levels were set for each type of animal manure, no distinct relationship between grain δ15N values and manuring levels was observed. For instance, grains fertilized with pig and cattle manure exhibited the highest δ15N values at low manuring level, while sheep and chicken manure resulted in highest values at high manuring level (Fig. 4). As for the upper and lower limits of grain δ15N values after fertilization, it can be observed that the minimum and maximum values of grain on ZL plots are higher than those on ZM and ZH plots. Similar trends were observed under cattle manure treatment, whereas both the upper and lower limits of grain values under sheep and chicken manure treatments at high manuring levels were higher than those at low or medium levels. Nevertheless, the grain values after fertilization with animal manure show no discernible correlation trend and the ranges largely overlap as the amount of fertilizer applied increases. This may be ascribed to the fact that one year of cultivation is too short to show a significant relationship, highlighting the need for further studies.

The process of manure influencing the grain δ 15N values

We present a preliminary depiction of the impact of manuring on grain δ15N values and human diets, encompassing the process from animal manure fermentation to human consumption of grains (Fig. 7). Our aim is to provide a reference for further investigations into the mechanism behind nitrogen stable isotope response to fertilization in millet, as well as establish isotopic criteria.

In accordance with previous studies, animal manure exhibits marked enrichment in 15N, which results in the rise of the grain δ15N values by manuring [19, 79,80,81]. We found that fermentation increased the δ15N values of animal manure by 0.2–5.0‰ while reducing its N content by 0.23–1.31% (Table 4 and Fig. 8), probably due to biochemical reactions such as denitrification and ammonia volatilization during fermentation [82]. These factors contribute to the high δ15N values of animal manure.

After applying animal manure to the soil, the offset in soil δ15N between the heading and mature period was 0.3‰. In contrast, Kanstrup et al. [20] reported significant soil δ15N offset (1.9‰) in Askov long-term arable soils. This implies that one year of animal manure addition may be inadequate to significantly influence the huge soil N pools, and the distinct N isotopic imprint on soil is potential for indicating past long-term manuring. Compared to soil, both grains and leaves displayed lower values, conforming to the preferential uptake of 14N from soil by plants [83]. As manured crops grew, the offset in grain δ15N between the heading and mature period was 3.1‰ (for Panicum), probably resulting from the gradual nitrogen accumulation [84]. Finally, this process contributes to the high δ15N values in humans consuming manured grains.

Conclusions

Our field experiment conducted in the core area of prehistoric millet agriculture in China has confirmed the significant impact of manuring on grain δ15N values of foxtail and broomcorn millets, with manured grains exhibiting a range of δ15N values from 2.7 to 9.3‰. The variation provides an alternative interpretation for the high δ15N values of humans in specific archaeological sites in northern China when reliable measurements of plant δ15N values are unavailable. The grain δ15N values are systematically lower than those observed in millet leaves, indicating that reconsideration is required for the δ15N offset between archaeological grains, domestic animals and humans. These findings underscore that determining the δ15N values of archaeobotanical remains is critical for accurately evaluating past manuring and dietary practices.

Availability of data and materials

All data supporting this study’s findings are presented in the manuscript.

References

Lu H, Zhang J, Liu K-B, Wu N, Li Y, Zhou K, et al. Earliest domestication of common millet (Panicum miliaceum) in East Asia extended to 10,000 years ago. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106(18):7367–72.

Liu X, Hunt HV, Jones MK. River valleys and foothills: changing archaeological perceptions of North China’s earliest farms. Antiquity. 2009;83(319):82–95.

Zhao Z. New archaeobotanic data for the study of the origins of agriculture in China. Curr Anthropol. 2011;52(S4):S295–306.

Yang X, Wan Z, Perry L, Lu H, Wang Q, Zhao C, et al. Early millet use in northern China. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109(10):3726–30.

Liu B, Wang N, Chen M, Wu X, Mo D, Liu J, et al. Earliest hydraulic enterprise in China, 5,100 years ago. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114(52):13637–42.

Zhao ZJ. Introduction of the origin of agriculture in China. Res Herit Preserv. 2019;4(1):1–7.

Filipović D, Meadows J, Corso MD, Kirleis W, Alsleben A, Akeret Ö, et al. New AMS 14C dates track the arrival and spread of broomcorn millet cultivation and agricultural change in prehistoric Europe. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):13698.

Deng ZH. The origin and early dispersal of foxtail and broomcorn millet. Collect Stud Archaeol. 2022;01:172–214.

Han JY. Several problems of Yangshao culture research in Miaodigou period. J Chin Antiq. 2021;02:51–4.

Han JY. Brief introduction of the origin, occurrence and development of early China in the cultural meaning. Jianghan Archaeol. 2015;3:67–74.

Wang JH. A preliminary study on the population scale and related issues in the Yangshao Period of Shaanxi Province. Archaeol Cult Relics. 2009;6:26–35.

Catt JA. The agricultural importance of loess. Earth Sci Rev. 2001;54(1–3):213–29.

Yao ZQ. Phytolith analysis of Taosi site in Xiangfen City and other sites. University of Science and Technology of China. 2006.

Qiao LM, Han H, He GH, et al. Changes of C, N, P contents in soil aggregates and their environmental risk across eroded landforms. J Soil Water Conserv. 2022;36(3):267–73.

Wang X, Fuller BT, Zhang P, Hu S, Hu Y, Shang X. Millet manuring as a driving force for the Late Neolithic agricultural expansion of north China. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):5552.

Yang J, Zhang D, Yang X, Wang W, Perry L, Fuller DQ, et al. Sustainable intensification of millet–pig agriculture in Neolithic North China. Nat Sustain. 2022;5(9):780–6.

Bogaard A, Heaton TH, Poulton P, Merbach I. The impact of manuring on nitrogen isotope ratios in cereals: archaeological implications for reconstruction of diet and crop management practices. J Archaeol Sci. 2007;34(3):335–43.

Bogaard A, Fraser R, Heaton TH, Wallace M, Vaiglova P, Charles M, et al. Crop manuring and intensive land management by Europe’s first farmers. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110(31):12589–94.

Fraser RA, Bogaard A, Heaton T, Charles M, Jones G, Christensen BT, et al. Manuring and stable nitrogen isotope ratios in cereals and pulses: towards a new archaeobotanical approach to the inference of land use and dietary practices. J Archaeol Sci. 2011;38(10):2790–804.

Kanstrup M, Thomsen IK, Andersen AJ, Bogaard A, Christensen BT. Abundance of 13C and 15N in emmer, spelt and naked barley grown on differently manured soils: towards a method for identifying past manuring practice. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2011;25(19):2879–87.

Styring AK, Ater M, Hmimsa Y, Fraser R, Miller H, Neef R, et al. Disentangling the effect of farming practice from aridity on crop stable isotope values: a present-day model from Morocco and its application to early farming sites in the eastern Mediterranean. Anthr Rev. 2016;3(1):2–22.

Styring AK, Charles M, Fantone F, Hald MM, McMahon A, Meadow RH, et al. Isotope evidence for agricultural extensification reveals how the world’s first cities were fed. Nat Plants. 2017;3(6):1–11.

Christensen BT, Jensen JL, Dong Y, Bogaard A. Manure for millet: grain δ15N values as indicators of prehistoric cropping intensity of Panicum miliaceum and Setaria italica. J Archaeol Sci. 2022;139:105554.

Dong Y, Bi X, Wu R, Belfield EJ, Harberd NP, Christensen BT, et al. The potential of stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis of foxtail and broomcorn millets for investigating ancient farming systems. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:1018312.

Wang X, Shang X, Hu YW. Evaluating the influence of manuring on stable isotope values of foxtail millet: an experimental planting study. Quat Sci. 2022;42(6):1806–14.

Chen X, Guo X, Wang W, Hu S, Yang M, Wu Y, et al. The subsistence patterns of the Shengedaliang site (~ 4,000 yr BP) revealed by stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes in northern Shaanxi, China. Sci China Earth Sci. 2017;60:268–76.

Mengjie C, Xue S, Yaowu H, Yan D, Yanfeng L, Songmei H. Farmers or nomads: isotopic evidence of human-animal interactions (770BCE to 221BCE) in Northern Shaanxi, China. Front Earth Sci. 2022;9:791323.

Hu SM, Yang T, Yang MM, et al. Research on faunal remains from the Miaoliang site in Jingbian County, northern Shaanxi on the formation of animal husbandry in China. Quat Sci. 2022;42(01):17–31.

Oi HY. Study on the effects of organic fertilization millet growing characters and yield. Jilin Agriculture University. 2004.

Yang JX, et al. Effects of different organic fertilizers on millet yield and quality. Shaanxi J Agric Sci. 2016;62(01):1–3.

Li JJ. Study on mechanism of high temperature composting of livestock manure and its application. China Agricultural University. 2004.

Research R. Guide to the classical and other long‐term experiments, datasets and sample archive. Lawes Agricultural Trust Harpenden; 2006.

Christensen BT, Thomsen IK, Petersen J. Long-term experiments at Askov experimental station. Long-term field experiments-a unique research platform. 2006:7.

Körschens M, Pfefferkorn A. The static fertilization experiment and other long-term field experiments. UFZ–Umweltforschungszentrum Leipzig-Halle GmbH. 1998.

Pechenkina EA, Ambrose SH, Xiaolin M, Benfer RA Jr. Reconstructing northern Chinese Neolithic subsistence practices by isotopic analysis. J Archaeol Sci. 2005;32(8):1176–89.

Barton L, Newsome SD, Chen F-H, Wang H, Guilderson TP, Bettinger RL. Agricultural origins and the isotopic identity of domestication in northern China. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106(14):5523–8.

Chen XL, Hu SM, Hu YW, Wang WL, Ma YY, Lü P, et al. Raising practices of Neolithic livestock evidenced by stable isotope analysis in the Wei River valley, North China. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 2016;26(1):42–52.

Dong Y, Chen S, Ambrose SH, Underhill A, Ling X, Gao M, et al. Social and environmental factors influencing dietary choices among Dawenkou culture sites, Late Neolithic China. Holocene. 2021;31(2):271–84.

Schoeninger MJ, DeNiro MJ. Nitrogen and carbon isotopic composition of bone collagen from marine and terrestrial animals. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1984;48(4):625–39.

Ambrose SH. Controlled diet and climate experiments on nitrogen isotope ratios of rats. In: Ambrose SH, Katzenberg MA, editors. Biogeochemical approaches to paleodietary analysis. Berlin: Springer; 2000. p. 243–59.

Katzenberg MA, Waters-Rist AL. Stable isotope analysis: a tool for studying past diet, demography, and life history. In: Katzenberg MA, Grauer AL, editors. Biological anthropology of the human skeleton. Hoboken: Wiley; 2018. p. 467–504.

Van Klinken GJ, Richards MP, Hedges BE. An overview of causes for stable isotopic variations in past European human populations: environmental, ecophysiological, and cultural effects. In: Ambrose SH, Katzenberg MA, editors. Biogeochemical approaches to paleodietary analysis. Berlin: Springer; 2000. p. 39–63.

Dürrwächter C, Craig OE, Collins MJ, Burger J, Alt KW. Beyond the grave: variability in Neolithic diets in Southern Germany? J Archaeol Sci. 2006;33(1):39–48.

Hedges RE, Reynard LM. Nitrogen isotopes and the trophic level of humans in archaeology. J Archaeol Sci. 2007;34(8):1240–51.

Kong GY, He SR, Chen XH. Current situation and analysis of Guanling hybrid wolfsbane planting. Today Anim Husb Vet Med. 2020;36(09):45.

Styring AK, Diop AM, Bogaard A, Champion L, Fuller DQ, Gestrich N, et al. Nitrogen isotope values of Pennisetum glaucum (pearl millet) grains: towards a reconstruction of past cultivation conditions in the Sahel, West Africa. Veget Hist Archaeobot. 2019;28:663–78.

Liu W, Wang Z. Nitrogen isotopic composition of plant-soil in the Loess Plateau and its responding to environmental change. Chin Sci Bull. 2009;54(2):272–9.

Codron D, Codron J, Lee-Thorp J, Sponheimer M, de Ruiter D, Brink J. Dietary variation in impala Aepyceros melampus recorded by carbon isotope composition of feces. Acta Zool Sin. 2006;52(6):1015–25.

Kohn MJ. You are what you eat. Science. 1999;283(5400):335–6.

Ambrose SH. Preparation and characterization of bone and tooth collagen for isotopic analysis. J Archaeol Sci. 1990;17(4):431–51.

Hu YW, Ambrose SH, Wang CS. Stable isotope analysis of human bones from Jiahu site. Sci China Earth Sci. 2007;2007(01):94–101.

Wei J, Feng B. Thoughts on the development process of the integration of agriculture and herding and the origin of animal husbandry in Northern China. West Reg Stud. 2020;04:79–93+168.

Zhang QC, Hu YC, Wei J, and Zhu H. Stable lsotope analysis of human bones unearthed from the Han Tomb of Nalintaohai in Bayannaoer City, Inner Mongolia. Acta Anthropol Sin, 2012:31407–414.

Zhao YN. C, N stable isotope analysis of animal bones from the Fuluta cemetery, Inner Mongolia. Shanxi University. 2020.

Zhang QC, Zhu H, Hu YW, Li YZ, Cao JN. Diet analysis of ancient residents in Xindianzi Cemetery, Helinger County. Inner Mongolia Cult Relics. 2006;01:87–91.

Zhao ZJ. The development of agriculture in the time of Yangshao Culture and the establishment of agricultural society: an analysis on the flotation result of Yuhuazhai site. Jianghan Archaeol. 2017;6:98–108.

Zhijun Z. Changes and development of ancient agriculture on Weihe Plain—an analysis of plant remnants excavated from Dongyang site in Huaxian District. Huaxia Archaeol. 2019;5:70–84.

Lin X, Wang YS, Yue Q, et al. Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis of human bones from burials of the Qin State in the Warring-States Period excavated at Guangzhong Prison in Shaanxi. Relics Museol. 2019;210(3):69–73.

Zhang GW, Hu YW, et al. Stable isotope analysis of subsistence mode of the Han Period people in the Guanzhong region and its difference from that of the northern nomadic people. Huaxia Archaeol. 2013;3:131–41.

Chen XL. The subsistence economic basis of social changes in the Xia and Shang dynasties in the Central Plains. Cult Relics South China. 2022;06:203–13+2.

Chen XL. The development of subsistence economy and social change in the Central Plains during the Neolithic Age: based on the research results of carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes in Henan Province. Cult Relics South China. 2021;1:179–90.

Pei DM, Hu YW, Yang YM, et al. Paleodietary analysis of humans from the Neiyangyuan Site of Xiangning, Shanxi Province. Acta Anthropol Sin. 2008;27(4):379–84.

Wang H, Wang WL, Hu SM, et al. The domestication and husbandry strategies of the pigs in the Wei River valley during the Neolithic Age. Archaeology. 2013;9:87–98+2.

Yuan J. Zooarchaeology of China. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press; 2014.

Hu YW. Research regulations, cognitive mistakes and analytical models in stable isotope bioarchaeology. Quat Sci. 2023;43(5):1503–12.

Quan-chao Z, Eng JT, Jian W, Hong Z. Paleodietary studies using stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes from human bone: an example from the Miaozigou Site, Qahar Youyi Qianqi, Inner Mongolia. Acta Anthropol Sin. 2010;29(03):270.

Ling X, Chen L, Xue XM, Zhao CC. Stable isotopic analysis of human bones from the Qingliang temple graveyard|Ruicheng county|Shanxi province. Quater Sci. 2010;30(2):415–21.

Sun YZ. Carbon and nitrogen stable lsotope of the human and animal bones from the Hengshui Cemetery. Shanxi University. 2019.

Sun YZ. Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope study of human bones from Dahekou Western Zhou Cemetery in Yicheng, Shanxi. Jilin University. 2023.

Tang M, Wang X, Hou K, Hou L. Carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analysis of the human bones from the Xiaonanzhuang site, Jinzhong, Shanxi: a preliminary study on the expansion of wheat in ancient Shanxi. China. 2018;37(2):318–30.

Hattersley P. δ13 values of C4 types in grasses. Funct Plant Biol. 1982;9(2):139–54.

Dong WM. Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses on modern foxtail millet and broomcorn millet of the Loess Plateau and the isotope fractions during carbonization. Lanzhou: The Master’s Thesis of Lanzhou University, 2012. pp. 1–67.

An C-B, Dong W, Chen Y, Li H, Shi C, Wang W, et al. Stable isotopic investigations of modern and charred foxtail millet and the implications for environmental archaeological reconstruction in the western Chinese Loess Plateau. Quat Res. 2015;84(1):144–9.

Choi W-J, Lee S-M, Ro H-M, Kim K-C, Yoo S-H. Natural 15 N abundances of maize and soil amended with urea and composted pig manure. Plant Soil. 2002;245:223–32.

Eghball B, Wienhold BJ, Gilley JE, Eigenberg RA. Mineralization of manure nutrients. J Soil Water Conserv. 2002;57(6):470–3.

Szpak P. Complexities of nitrogen isotope biogeochemistry in plant-soil systems: implications for the study of ancient agricultural and animal management practices. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:288.

Wang X. Stable isotopic study of manuring management in the Middle Yellow River Valley China during the late Neolithic. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences. 2018.

Choi W-J, Kwak J-H, Lim S-S, Park H-J, Chang SX, Lee S-M, et al. Synthetic fertilizer and livestock manure differently affect δ15N in the agricultural landscape: a review. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2017;237:1–15.

Kreitler CW, Jones DC. Natural soil nitrate: the cause of the nitrate contamination of ground water in Runnels county, Texasa. Groundwater. 1975;13(1):53–62.

Heaton TH. Isotopic studies of nitrogen pollution in the hydrosphere and atmosphere: a review. Chem Geol. 1986;59:87–102.

Kendall C. Tracing nitrogen sources and cycling in catchments. In: Kendall C, Mcdonnell JJ, editors. Isotope tracers in catchment hydrology. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1998. p. 519–76.

Choi W-J, Chang SX, Kwak J-H, Jung J-W, Lim S-S, Yoon K-S, et al. Nitrogen transformations and ammonia volatilization losses from 15N-urea as affected by the co-application of composted pig manure. Can J Soil Sci. 2007;87(5):485–93.

Bateman AS, Kelly SD, Jickells TD. Nitrogen isotope relationships between crops and fertilizer: implications for using nitrogen isotope analysis as an indicator of agricultural regime. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53(14):5760–5.

Huang JL, Zou YB, Peng SB. Nitrogen uptake, distribution by rice and its losses from plant tissues. Plant Nutr Fertil Sc. 2004;06:579–83.

Acknowledgements

Lu Yuxin of the Bio-Agriculture Institute of Shaanxi, Cui Mengjie, Jin Dan and Li Ruixue of University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, provided assistance with crop planting and sampling.

Funding

This study received financial support from the Projects of the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant agreement number 42277441), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant agreement number 21BKG040) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant agreement number E2ET0910X2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XS designed the research. ZZF performed the experiments. HYOY sampled and analyzed the samples. HYOY and JCL made contributions to the acquisition of data. HYOY and XS analyzed the data, and were both the major contributors in writing the manuscript. YWH, XQL and JCL made substantial contributions to the revision. All authors read the final manuscript. HYOY and XS approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ouyang, H., Shang, X., Hu, Y. et al. Experimental archaeological study in China: implications for reconstruction of past manuring and dietary practices indicated by δ15N values of Setaria italica and Panicum miliaceum. Herit Sci 12, 55 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01168-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01168-7