Abstract

Background

Global change is causing an increase in the incidence of natural and anthropogenic disturbances on forests, which frequently interact synergistically and promote changes in forest structure, composition and functioning. In this study we evaluate the regeneration of Pinaceae and Fagaceae species in pure and mixed stands in Mexico to determine if current regeneration patterns are indicative of changes in the relative dominance of these two tree families, as observed in other temperate regions. We also identify the environmental factors that determine the regeneration patterns of Pinaceae and Fagaceae species in these forests.

Results

We use data from two consecutive surveys of the National Inventory of Forests and Soils of Mexico (INFyS), obtained in 2004–2009 and 2009–2014. Our results show that the spatial patterns of regeneration are affected by forest structure, by climate, by the type and intensity of disturbances and by land tenure. Importantly, the presence and abundance of Fagaceae regeneration is generally higher than that of Pinaceae, and tends to be favoured (relative to Pinaceae) under warmer climates and by the presence of wildfires.

Conclusions

The higher regeneration of Fagaceae relative to Pinaceae under warmer and fire-prone conditions could have important impacts on the composition and functioning of Mexican temperate forests under ongoing climate change, as well as affect their resilience to future disturbances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Climate change is causing an increase in the incidence of disturbances such as drought, natural fires, pests and diseases (Brecka et al. 2018; Prăvălie 2018), which can drive rapid changes in forests (Allen et al. 2015). Moreover, recent anthropogenic changes due to forest exploitation, extensive grazing and land use changes are also modifying the composition and structure of forest ecosystems (Burgi et al. 2000; Gimmi et al. 2010; Easterday et al. 2018). Examples include the increase of drought-tolerant and slow-growing species in tropical and temperate environments (Feeley et al. 2011; Allen et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2018), substitution of late-successional by early-successional conifers caused by the increase in the frequency of fires associated with climate change (Carcaillet et al. 2001; Searle and Chen 2017) or the transition from conifers to broadleaf species in temperate forests (Rigling et al. 2013; Vayreda et al. 2016; Alfaro-Reyna et al. 2018).

To understand and forecast shifts in forest composition, it is essential to characterize the regeneration patterns of tree species (cf. Martínez-Vilalta and Lloret 2016 for the specific case of drought-induced forest decline), including the conditions that allow the establishment and survival of new recruits of different species, as well as their response under different natural and anthropogenic disturbance regimes (Denslow 1980). Regeneration dynamics can be understood in terms of tolerance to limiting resources, such as the availability of water and nutrients or the exposure to light (Agyeman et al. 1999; Woodward et al. 2004). Shade-intolerant species tend to have a higher growth rate under direct light conditions and usually dominate the low canopies initially, but when canopies close they are typically replaced by species that tolerate more shaded conditions, at least in their early stages of development, which are usually classified as late-successional species (Swaine and Whitmore 1988).

Temperate forest ecosystems occupy 26% of the world’s forest cover and dominate large areas of the northern hemisphere (Keenan et al. 2015; Riitters et al. 2016). These forests are largely dominated by members of the Fagaceae and Pinaceae families. Many Pinaceae are characterized as being intolerant to shade and require open areas with little plant cover to establish (Ramírez-Marcial et al. 2001; Quintana-Ascencio et al. 2004; Coomes et al. 2005), although many exceptions exist (e.g. Stephens and Gill 2005; González-Tagle et al. 2008). Thus, in xeric environments, Pinaceae may require tree protection or nursery for the successful recruitment of seedlings (e.g. Gómez-Aparicio et al. 2004). Edaphic properties combined with water availability significantly influence the establishment of Pinus species (Barton 1993; Carnicer et al. 2014; Pompa-García et al. 2018). On the other hand, most Fagaceae are considered semi-tolerant to shade, as they can live under closed canopies during the juvenile and adult stages, although in the early stages of life light requirements are sometimes greater (Galindo-Jaimes et al. 2002; Berg et al. 2018). In general, oaks have a greater range of tolerance to drought than pines (Rigling et al. 2013; Montes-Hernández and López-Barrera 2013; Carnicer et al. 2014) and also have a high capacity of resprouting after a disturbance (Cooper et al. 2018). As a result, replacement of pine-dominated forests by oak woodlands and shrublands after large fires has been documented in recent decades in North America (Goforth and Minnich 2008; Barton and Poulos 2018) and Europe (Rodrigo et al. 2004). In addition, several studies have reported increased regeneration of oaks relative to pines in temperate forests where these two groups coexist, particularly under warm and dry conditions in Southern Europe (Vayreda et al. 2013; Carnicer et al. 2014).

Temperate forests of Mexico, due to their high diversity of pines and oaks, are considered a center of diversification of those groups (Challenger and Soberón 2008), hosting 61 species of Pinaceae (Gernandt and Pérez-de la Rosa 2014) and 125 species of Fagaceae (Valencia-A 2004; Valencia-A and Gual-Díaz 2014). The patterns of distribution of these forests reflect the historically common disturbances in the region, such as forest thinning and wood extractions, grazing and fires (Pompa-García et al. 2018). Several studies have analyzed the local regeneration patterns of pine-oak forests after different types of disturbances in Mexico (Galindo-Jaimes et al. 2002; Rodríguez-Trejo and Fulé 2003; Asbjornsen et al. 2004; López-Barrera and Newton 2005; González-Tagle et al. 2008). However, there is little information on the regeneration of both groups at a regional scale for different forest types and how it has been influenced by recent climate change.

In this study we analyze the patterns of Pinaceae and Fagaceae regeneration in Mexican forests using data from two consecutive surveys of the National Forest and Soil Inventory of Mexico (INFyS, CONAFOR 2015). Firstly, we evaluate the regeneration of Pinaceae and Fagaceae in forests with pure and mixed overstory to determine if current regeneration patterns are indicative of forest composition shifts, as observed in other temperate regions. Secondly, we identify the environmental factors that determine the regeneration patterns of pines and oaks in these forests. We hypothesize that Fagaceae will tend to regenerate better than Pinaceae in all forests where these two species groups coexist in the ovestory, and that this pattern will be exacerbated under warmer conditions and in areas subjected to intense and frequent disturbance regimes.

Materials and methods

Study area

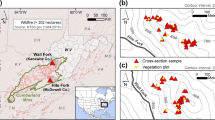

The study area covers the whole distribution of pine, oak, and pine-oak forests in Mexico (between 86° and 117° W, and between 14° and 32° N) (Fig. 1), which are mainly distributed in the Sierra Madre Occidental, in the eastern slope of the Sierra Madre Oriental and in some parts of the southern mountain systems and the humid subtropical zone (Miranda and Hernández-X 1963; INEGI 2014). These forests are largely dominated by species of Pinus, Quercus or both. They are distributed mainly in regions of temperate and cold climates, rainy or subhumid with summer rains (climate Cw, according to the Köppen classification). This climate is characterized by a well-defined dry season in winter and spring, with a mean annual temperature of 10–20 °C and annual precipitation between 800 and > 2000 mm per year. In some parts of the eastern Sierra Madre and southern mountain systems, a small proportion of pine-oak forests can be found in the humid subtropical zone (climate Cf), a very humid area where it rains all year and there is not a well-defined dry season (Miranda and Hernández-X 1963; INEGI 2014). In this area mean annual temperature is 10–22 °C and an annual rainfall ranges between 800 and 4700 mm.

Map of the study area showing the location of the 5458 conglomerates of the INFyS that were used to evaluate the regeneration of Pinaceae vs Fagaceae in Mexico. Sampling plots (dots) are overlaid on a mean annual temperature map. The colour of the dots represents the type of forest: oak-dominated overstory (red), pine-dominated overstory (green) or mixed pine-oak overstory (yellow)

National Forest and soil inventory of Mexico

The study is based on the information obtained from the National Forest and Soil Inventory of Mexico, hereinafter INFyS. This inventory contains around 26,000 sampling units (conglomerates) homogeneously distributed throughout the country, following a rectangular grid with a distance between conglomerates that varies from 5 km in temperate regions to 20 km in arid zones (CONAFOR 2015). The INFyS follows a systematic scheme of stratified sampling, using conglomerates of plots as basic sampling units. The conglomerates are circular with 56.42 m radius (1 ha). Each conglomerate contains 4 sub-plots of 400 m2 each, 1600 m2 per conglomerate in total, geometrically distributed in the form of an inverted “Y”. We used the data from the inventories carried out in 2004–2009 (CONAFOR 2012) and 2009–2014 (CONAFOR 2018). The interval between the two inventories for a given sampling unit was on average 5 years but varied between 2 and 9 years depending on the conglomerate.

From all INFyS conglomerates we selected only those for which Pinaceae and/or Fagaceae species were present in at least one of the two inventories (2004–2009, 2009–2014). In addition, we only included conglomerates that met the following criteria: (i) the same plots had been measured (resurveyed) in the two inventories; (ii) total basal area was > 2 m2·ha− 1 in the first survey so that very open forests were excluded; and (iii) did not contain human structures and roads and had not been severely affected by external impacts such as mining (according to INFyS surveys). Of all the conglomerates sampled in the INFyS, a total of 5458 met these criteria and were selected for this study. Only 517 plots (< 10%) were discarded for not meeting criteria (ii) and (iii) indicated above. Our analyses thus refer specifically to pine forests, oak forests and mixed pine-oak forests in a very broad sense, as determined based on the presence of overstory trees of the corresponding families according to INFyS surveys (see ‘Stand characteristics’ below). We note, however, that not all the natural distribution of these forest types in Mexico is included, as many of them were not sampled by INFyS or did not meet the previous selection criteria.

a) Stand characteristics

At the conglomerate level, the following variables recorded in the INFyS surveys were included in our analyses: basal area (m2·ha− 1) of all Pinaceae and Fagaceae species present (separately by family), total stand basal area (m2·ha− 1), the occurrence of several disturbances, and land tenure (private; public, state owned; and social property, including the “ejido” and the communal properties). Overstory composition was determined according to the composition of the overstory (basal area of Pinaceae and Fagaceae species), and each conglomerate was classified in one of the following categories: Oak, for conglomerates where only Fagaceae were present in the overstory; Pine, for conglomerates were only Pinaceae were present in the overstory; and Mixed, for conglomerates where the two tree families were recorded in the overstory. We note that this classification may differ locally from standard vegetation types at the landscape level (e.g. those from INEGI (2014) vegetation maps). Nevertheless, we preferred to use a classification based on local, plot-level composition in our case, as in combination with the regeneration information analysed here provides richer and more accurate information on the likely population dynamics of the studied forests. Basal area measurements were averaged between the two INFyS surveys. Disturbance occurrence, including wildfires, grazing, pests and diseases, and wood extractions, was determined according to the information recorded during INFyS surveys. In these surveys, the intensity of each disturbance was evaluated using a five-level ordinal scale. For simplicity, we reclassified these levels into two categories for each type of disturbance: low (no, barely noticeable or low impact in the two surveys) and high impact (medium or high impact as recorded in at least one of the surveys).

b) Regeneration of tree species

Regeneration was sampled at the INFyS surveys as follows. At the center of each of the four sub-plots of 400 m2 of each conglomerate, a circle of 12.56 m2 (a total of 50.24 m2 per conglomerate) was established where the regeneration was assessed. All individuals greater than 25 cm in height were considered as regeneration, up to the height they reached, provided that their diameter at breast height (DBH) was less than 7.5 cm. All individuals of each genus were counted and classified into three height classes: 25–150, 150–275 and > 275 cm. In this study, these height categories were reclassified into two classes: 25–150 cm height, which we called “saplings”, and > 150 cm, which we called “small trees”. Total Pinaceae and Fagaceae regeneration (individuals·ha− 1) were averaged between the two INFyS surveys for each conglomerate. By doing so we reduced the effect of temporal variability in regeneration on our results, which is particularly important considering that sampling years differed among conglomerates. The fact that we averaged the values from two inventories per conglomerate (instead of studying the changes between them) also implies that the effect of heterogeneous time intervals between surveys across conglomerates is likely to be negligible.

Climatic data

Bioclimatic variables were extracted from Worldclim (Hijmans et al. 2005), a free database of global climatic layers with a spatial resolution of approximately 1 km2. The geographical coordinates of all conglomerates were superimposed to climatic layers using the ArcGis software to obtain the annual precipitation (mm) and the mean annual temperature (°C) of each conglomerate location.

Data analyses

The two response variables, sapling regeneration and small tree regeneration, had a large proportion of zeros (that is, conglomerates without regeneration of either saplings or small trees) (7.2% for saplings and 27.7% for small trees), and no transformation could satisfy the normality assumption. For this reason, each of these variables was analyzed in two steps. First, we transformed each variable to a dichotomous one, indicating the presence/absence of regeneration (of saplings or small trees) in each conglomerate. We used generalized, mixed-effects linear models with a binomial distribution and a logit link function to analyze the presence of saplings and small trees (considered separately). As explanatory variables, we included the Family of the regeneration (Fagaceae, Pinaceae) and its interaction with: overstory composition (Oak, Mixed, Pine), total basal area (m2·ha− 1) of the conglomerate, mean annual temperature (°C), annual precipitation (mm), land tenure (private, public, social), forest fires (low vs. high impact), grazing (low vs. high impact), pests and diseases (low vs. high impact), and wood extractions (low vs. high impact). We included Conglomerate nested in State (N = 28) as random factors. Conglomerate was included to account for the fact that data for the two families (Fagaceae, Pinaceae) was paired at the conglomerate level. State accounted for the effect of spatial autocorrelation at relatively large spatial scales (the average size of a Mexican state is 63,481 km2), resulting for instance from differences in legislation or historical land-use between states.

In a second step, we used general, mixed-effects linear models to model regeneration abundance (of saplings or small trees) in conglomerates with at least one regenerating individual. As not all conglomerates had regeneration of the two families, we carried out four different linear models: two for saplings and small trees of Pinaceae, and two for saplings and small trees of Fagaceae. The explanatory variables were the same as in the models for regeneration presence except the family of the regeneration (and its interactions with the other variables), which could not be considered in this case. We again used mixed-effect models but in this case the only random effect was State. Regeneration abundance was log-transformed in all cases to satisfy normality assumptions. Some explanatory variables were also log- or square root-transformed, as indicated in the corresponding tables in the Results, to improve the distribution of model residuals. Stepwise model selection was applied starting from the saturated model and removing the least significant term until there was no further decrease in the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). All statistical analyses were carried out with the R software (version 3.2.2, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Regeneration of Pinaceae and Fagaceae as a function of overstory composition

The presence of Fagaceae saplings was very common in the conglomerates with oak and mixed overstory, where the percentage of conglomerates with Fagaceae saplings was > 80% (Fig. 2). Half of the conglomerates with pine overstory had Fagaceae saplings (Fig. 2). On the other hand, Pinaceae saplings appeared in 69% and 56% of forests with pine and mixed overstory, respectively, but only in 4% of those with oak overstory. These patterns were qualitatively similar, albeit with lower overall values, for small trees (Fig. 2).

Densities of Pinaceae and Fagaceae saplings and young trees (for the conglomerates showing regeneration) also varied depending on overstory composition (Fig. 3). Thus, Fagaceae saplings were more abundant than those of Pinaceae under the three overstory compositions, while those of Pinaceae had a particularly low density in forests with oak overstory (Fig. 3). On the other hand, small Fagaceae trees were more abundant than small pines in forests with mixed and particularly oak overstory, where small pines were basically absent (Fig. 3). Only in forests with pine overstory the densities of small pine trees were larger (approximately double) than those of small Fagaceae trees (Fig. 3).

Factors affecting the presence of saplings and small trees of Pinaceae and Fagaceae

Consistent with the previous results, the generalized linear mixed-effects model indicated that the presence of Fagaceae and Pinaceae saplings was higher under canopies dominated by trees of their own family. Fagaceae presence was higher in forests with oak and mixed overstory, whereas saplings of the two families were similarly present in conglomerates with pine overstory (Table 1). Mean temperature had a positive effect on the presence of Fagaceae saplings but a strong negative effect on Pinaceae saplings (Fig. 4a, Table 1). The effect of precipitation was positive and similarly small for both families. Wildfires had a positive effect on the presence of Fagaceae saplings that was not observed for Pinaceae (Fig. 5a, Table 1); whereas the opposite occurred for grazing effects, which only affected (negatively) the presence of Fagaceae saplings (Fig. 6a, Table 1).

Effect of the interaction between family and mean annual temperature on the presence (proportion) of Fagaceae vs. Pinaceae saplings (a) and small trees (b) in the forests of Mexico, according to the model presented in Table 1. Significant relationships are denoted by an asterisk (*). Grey bands indicate the confidence intervals (standard error) around the estimated effects

Effect of the interaction between family and wildfire intensity (Low vs High) on the presence (proportion) of Fagaceae vs. Pinaceae saplings (a) and small trees (b) in the forests of Mexico, according to the model presented in Table 1. Significant effects are denoted by an asterisk (*). Error bars indicate the standard error of the estimate

Effect of the interaction between family and grazing intensity (Low vs High) on the presence (proportion) of Fagaceae vs. Pinaceae saplings (a) and small trees (b) in the forests of Mexico, according to the model presented in Table 1. Significant effects are denoted by an asterisk (*). Error bars indicate the standard error of the estimate

The overall patterns were similar when considering the regeneration of small trees (Table 1). The effect of temperature was not significant for Fagaceae, whereas it was again strongly negative for Pinaceae (Fig. 4b). On the other hand, the effect of precipitation was not significant for small trees (Table 1). The social land tenure was associated with higher presence of small Pinaceae trees, whereas this effect was not observed for Fagaceae. Wildfires had a negative effect on the presence of Pinaceae small trees, whereas the effect was neutral for Fagaceae (Fig. 5b, Table 1). Grazing was associated with higher presence of small Pinaceae trees and lower presence of small Fagaceae trees (Fig. 6b, Table 1).

Factors affecting the abundance of saplings and small trees of Pinaceae and Fagaceae

Overstory composition had a significant effect on the general linear mixed-effects models carried out for the abundance of the saplings of the two families separately. Density of both Pinaceae and Fagaceae saplings was higher in forests with mixed and pine overstory than in those with oak overstory (Table 2, see also Fig. 3). Basal area contributed positively to the abundance of Pinaceae saplings but negatively to that of Fagaceae (Table 2). Concerning climatic factors, temperature negatively affected the abundance of saplings of both families, although the effect was stronger for Fagaceae, while precipitation had always a positive effect (Table 2). Wood extractions increased the abundance of Pinaceae saplings only, whereas fires had a positive effect and grazing a negative effect on the abundance of Fagaceae saplings only (Table 2). Finally, the social tenure of the land was associated to higher abundance of Pinaceae saplings.

In the general linear mixed-effects models for the abundance of small trees the effect of overstory composition was not significant for either of the two families (Table 2). As in the case of the sapling models, basal area contributed positively to the abundance of small Pinaceae trees but negatively affected that of Fagaceae (Table 2). Temperature negatively affected the abundance of both families, while precipitation had a positive effect on the abundance of small Pinaceae trees only. As far as disturbances are concerned, fires were associated with higher abundance of small Fagaceae trees and had a negative effect on Pinaceae, while grazing was associated to lower abundance of small Fagaceae trees only (Table 2). Finally, the abundance of small Fagaceae trees was higher under social tenure, but this effect was not observed for Pinaceae.

Discussion

Our results show that regeneration patterns in pine-oak Mexican forests differ substantially between Pinaceae and Fagaceae, with regeneration of Fagaceae tending to dominate over that of Pinaceae in forests with oak and mixed overstory. We acknowledge that this outcome and the other results reported here need to be interpreted with caution, as the information provided by the INFyS is relatively coarse, as in any nationwide forest inventory, and may not be accurate enough to characterize detailed ecological patterns, particularly at local scales. However, nationwide forest inventories remain an unvaluable source of information to assess regeneration patters at regional scales or broader, and hence we restrict our discussion to general patterns and associations identified at the country scale. The fact that, overall, saplings and small trees of Pinaceae and Fagaceae were generally more abundant under canopies dominated by trees of their own family and in mixed forests than in forests dominated exclusively by the other family indicates that regeneration is largely determined by overstory composition. This does not support the expected greater shade tolerance of Fagaceae relative to Pinaceae species, and likely reflects the diversity of shade tolerance attributes within families, especially among the pines (McCune 1988; Retana et al. 2002).

Climate is an important determinant of successional dynamics of pine-oak species in Mexico (Roncal-García et al. 2008; van Zonneveld et al. 2009; Figueroa-Rangel et al. 2012). Importantly, our results suggest that the effect of climate differs between families, as warm temperatures benefited the presence of saplings and, to a lesser extent, the presence of small trees of Fagaceae, but strongly reduced the presence of saplings and small trees of Pinaceae. This result can have important implications under ongoing climate warming and the corresponding increase in the frequency and intensity of hotter droughts, which has already been reported in central America (Margolis et al. 2017). As expected, precipitation generally benefited the regeneration of both families. In northern Mexico, the highest peaks of pine and oak regeneration have been associated with unusually wet and fire-free periods (Meunier et al. 2014).

Our results show that disturbances also determined regeneration patterns and had differential impacts between families. Although disturbance effects have to be interpreted with caution, because they rely on punctual information recorded exclusively during INFyS surveys, our models suggest that forest fires reduced the presence and abundance of Pinaceae regeneration relative to Fagaceae. This general result certainly masks large variability in fire impacts on regeneration depending on fire regimes (Fulé and Covington 1998) and local conditions (climate, dominant species; Rodríguez-Trejo and Fulé 2003). However, the fact that our results were highly consistent among regeneration classes (saplings vs. small trees) and for both the presence and abundance of regeneration (Tables 1 and 2) gives us confidence on the strength of this result at the country scale.

In the second half of the twentieth century fire regimes changed drastically in many Mexican temperate forests, which has caused long periods without fires, promoting a greater recruitment of coniferous species, as well as a large accumulation of igneous fuels (Minnich et al. 2000; Rodríguez-Trejo and Fulé 2003; Cortés Montaño et al. 2012). This accumulation of fuel has promoted large forest fires in some areas, which are known to promote oak woodlands and shrublands over pine forests (Barton and Poulos 2018). The predominance of oak species in post-fire stands is favoured by their sprouting capacity after disturbance (Fulé and Covington 1998; Aguilar et al. 2012; Stambaugh et al. 2017). In addition, Quercus species have deep root systems that help them prevent water stress, which may be advantageous in the dry, post-fire conditions (Davis and Mooney 1986; Anderegg et al. 2015). In contrast, relatively few Mexican pine species have specific mechanisms to cope with fires and establish themselves after a large fire, such as a thick bark, serotine cones or resprouting capacity (Rodríguez-Trejo and Fulé 2003).

Besides wildfires, livestock grazing was the disturbance recorded in this study that was associated to greater differences between Fagaceae and Pinaceae regeneration. The strong negative impact of grazing on the presence and abundance of seedlings and small trees of Fagaceae, which was not observed for Pinaceae, can be explained by the lower palatability and generally higher tolerance to browsing of pines (Wahlenberg et al. 1939; Hernández et al. 2000). Differential human management and use of these two species groups may also contribute to explain the observed regeneration patterns, as acorn consumption, trampling and browsing of the young shoots cause a strong reduction in the establishment and growth of oaks in browsed areas (Quintana-Ascencio et al. 2004; Hernández et al. 2000). The importance of management and land use is consistent with previous reports (Heyerdahl and Alvarado 2003; García-Barrios and González-Espinosa 2004; Works and Hadley 2004) and with the effect of land tenure in our results, suggesting that the abundance of Pinaeae saplings and small Fagaceae trees may be favored under a social tenure. Although wood extractions had a relatively small effect in our models, 75% of timber extractions in Mexico correspond to pine species (Segura 2000), which should have strong effects on regeneration patterns and stand dynamics. In addition, we acknowledge that other factors not included in our analyses affect regeneration success and likely contribute to the observed differences between families.

Factors related to stand structure and development also affected the regeneration of pine-oak forests in Mexico. The abundance of Pinaceae was favored in high basal area stands, while the abundance of Fagaceae saplings and small trees was negatively affected by total basal area. These results challenge the view that Pinaceae tend to be more early-successional than Fagaceae. However, they are consistent with several studies reporting that colonization of broadleaf species is low in mature, high basal area forests dominated by Pinaceae (Camacho-Cruz et al. 2000; Ramírez-Marcial et al. 2001; Galindo-Jaimes et al. 2002; Alba et al. 2003; García-Barrios and González-Espinosa 2004; Ramírez-Marcial et al. 2006). As already mentioned, within-family diversity in shade tolerance is high and oak regeneration may require the presence of open spaces upper in the tree canopy (Stambaugh et al. 2002; López-Barrera et al. 2006; Pérez et al. 2013), which are dependent on specific disturbance regimes (González-Espinosa et al. 1991; Galindo-Jaimes et al. 2002; Quintana-Ascencio et al. 2004; Meunier et al. 2014).

Conclusion

Overall, our results show that in Mexican forests the regeneration of Fagaceae tends to dominate over that of Pinaceae, although this depends on overstory composition and disturbance regime. The fact that Fagaceae regeneration seems to be favoured, relative to Pinaceae, under warmer climates and in the presence of wildfires, suggests that ongoing climate change (Sáenz-Romero et al. 2010) could favour the predominance of oaks, particularly in drier areas (Melo et al. 2010; Meunier et al. 2014). These changes are consistent with global patterns reported for global temperate forests (Alfaro-Reyna et al. 2018) and with current growth trends in Mexican forests (Alfaro-Reyna 2019). Although the final outcome will critically depend on human management and land use, the structure, composition and functioning of many Mexican pine-oak forests could be strongly modified (Gómez-Mendoza and Arriaga 2007; Gómez-Mendoza et al. 2008; Galicia et al. 2013). This would also have an important socioeconomic impact, due to the key role of Mexican pine-oak forests as providers of ecosystem services (Segura 2000) and the fact that many local communities depend directly on forest products for their subsistence (FAO 2010). Further research assessing mid-term temporal dynamics is needed to confirm the trends reported in this study, as well as to provide more detailed understanding of the corresponding spatial patterns and the implications for forest resilience under future disturbance regimes.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be made available on demand.

References

Aguilar R, Ghilardi A, Vega E, Skutsch M, Oyama K (2012) Sprouting productivity and allometric relationships of two oak species managed for traditional charcoal making in Central Mexico. Biomass Bioenergy 36:192–207

Agyeman VK, Swaine MD, Thompson J (1999) Responses of tropical forest tree seedlings to irradiance and the derivation of a light response index. J Ecol 87:815–827

Alba M, González M, Ramírez N, Castillo M (2003) Determinantes de la distribución de Pinus spp. en la Altiplanicie Central de Chiapas, México. Bol Soc Bot Méx 73:7–15

Alfaro-Reyna T (2019) Recent dynamics of Fagaceae and Pinaceae in temperate forests in Mexico and worldwide. PhD Thesis, Autonomous University of Barcelona

Alfaro-Reyna T, Martínez-Vilalta J, Retana J (2018) Is there a substitution of Pinaceae by Fagaceae in temperate forests at the global scale? Glob Planet Chang 166:41–47

Allen MS, Thapa V, Arévalo JR, Palmer MW (2012) Windstorm damage and forest recovery: accelerated succession, stand structure, and spatial pattern over 25 years in two Minnesota forests. Plant Ecol 213:1833–1842

Allen CD, Breshears DD, McDowell NG (2015) On underestimation of global vulnerability to tree mortality and forest die-off from hotter drought in the Anthropocene. Ecosphere 6:1–55

Anderegg WRL, Flint A, Huang C, Flint L, Berry JA, Davis FW, Sperry JS, Field CB (2015) Tree mortality predicted from drought-induced vascular damage. Nat Geosci 8:367–371

Asbjornsen H, Vogt KA, Ashton MS (2004) Synergistic responses of oak, pine and shrub seedlings to edge environments and drought in a fragmented tropical highland oak forest, Oaxaca, Mexico. Forest Ecol Manag 192:313–334

Barton AM (1993) Factors controlling plant distributions: drought, competition, and fire in montane pines in Arizona. Ecol Monogr 63:367–397

Barton AM, Poulos HM (2018) Pine vs. oaks revisited: conversion of Madrean pine-oak forest to oak shrubland after high-severity wildfire in the Sky Islands of Arizona. Forest Ecol Manag 414:28–40

Berg EC, Zarnoch SJ, McNab WH (2018) Twenty-year survivorship of tree seedlings in wind-created gaps in an upland hardwood forest in the eastern US. New Forest. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11056-018-9685-x

Brecka AFJ, Shahi C, Chen HYH (2018) Climate change impacts on boreal forest timber supply. Forest Policy Econ 92:11–21

Burgi M, Russell EWB, Motzkin G (2000) Effects of postsettlement human activities on forest composition in the North-Eastern United States: a comparative approach. J Biogeogr 27:1123–1138

Camacho-Cruz A, González-Espinosa M, Wolf JHD, de Jong BHJ (2000) Germination and survival of tree species in disturbed forests of the highlands of Chiapas, Mexico. Can J Bot 78:1309–1318

Carcaillet C, Bergeron Y, Richard PJH, Fréchette B, Gauthier S, Prairie YT (2001) Change of fire frequency in the eastern Canadian boreal forests during the Holocene: does vegetation composition or climate trigger the fire regime? J Ecol 89:930–946

Carnicer J, Coll M, Pons X, Ninyerola M, Vayreda J, Peñuelas J (2014) Large-scale recruitment limitation in Mediterranean pines: the role of Quercus ilex and forest successional advance as key regional drivers. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 23:371–384

Challenger A, Soberón J (2008) Los ecosistemas terrestres. Capital natural de México, vol I: Conocimiento actual de la biodiversidad. CONABIO, México, pp 87–108

CONAFOR (2012) Inventario Nacional Forestal y de Suelos. Informe 2004–2009. Zapopan, Jalisco, México

CONAFOR (2015) Inventario Nacional Forestal y de Suelos. Procedimiento de muestreo, Guadalajara

CONAFOR (2018) Inventario Nacional Forestal y de Suelos. Informe de resultados 2009–2014. Zapopan, Jalisco, México

Coomes DA, Allen RB, Bentley WA, Burrows LE, Canham CD, Fagan L, Forsyth DM, Gaxiola-Alcantar A, Parfitt RL, Ruscoe WA, Wardle DA, Wilson DJ, Wright EF (2005) The hare, the tortoise and the crocodile: the ecology of angiosperm dominance, conifer persistence and fern filtering. J Ecol 93:918–935

Cooper CE, Muir JP, Morgan CLS, Moore GW (2018) Tortoise or hare: will resprouting oaks or reseeding pines dominate following severe wildfire? Forest Ecol Manag 408:54–66

Cortés Montaño C, Fulé PZ, Falk DA, Villanueva-Díaz J, Yocom LL (2012) Linking old-growth forest composition, structure, fire history, climate and land-use in the mountains of northern México. Ecosphere. https://doi.org/10.1890/ES12-00161.1

Davis SD, Mooney HA (1986) Water use patterns of four co-occurring chaparral shrubs. Oecologia 70:172–177

Denslow JS (1980) Patterns of plant species diversity during succession under different disturbance regimes. Oecologia 46:18–21

Easterday K, McIntyre P, Kelly M (2018) Land ownership and 20th century changes to forest structure in California. Forest Ecol Manag 422:137–146

FAO (2010) Evaluación de los recursos forestales mundiales 2010 Informe Nacional México. Rome, p 98

Feeley KEJ, Davies STJ, Perez RO, Hubbell STP (2011) Directional changes in the species composition of a tropical forest. Ecology 92:871–882

Figueroa-Rangel BL, Willis KJ, Olvera-Vargas M (2012) Late-Holocene successional dynamics in a transitional forest of west-Central Mexico. Holocene 22:143–153

Fulé PZ, Covington WW (1998) Spatial patterns of Mexican pine-oak forests under different recent fire regimes. Plant Ecol 134:197–209

Galicia L, Gómez-Mendoza L, Magaña V (2013) Climate change impacts and adaptation strategies in temperate forests in Central Mexico: a participatory approach. Mitig Adapt Strat Gl 20:21–42

Galindo-Jaimes L, González-Espinosa M, Quintana-Ascencio P, García-Barrios L (2002) Tree composition and structure in disturbed stands with varying dominance by Pinus spp. in the highlands of Chiapas, México. Plant Ecol 162:259–272

García-Barrios L, González-Espinosa M (2004) Change in oak to pine dominance in secondary forests may reduce shifting agriculture yields: experimental evidence from Chiapas, Mexico. Agric Ecosyst Environ 102:389–401

Gernandt DS, Pérez-de la Rosa JA (2014) Biodiversidad de Pinophyta (coníferas) en México. Rev Mex Biodivers 85:126–133

Gimmi U, Wohlgemuth T, Rigling A, Hoffmann CW, Bürgi M (2010) Land-use and climate change effects in forest compositional trajectories in a dry Central-Alpine valley. Ann For Sci 67:701–701

Goforth BR, Minnich RA (2008) Densification, stand-replacement wildfire, and extirpation of mixed conifer forest in Cuyamaca rancho State Park, southern California. Forest Ecol Manag 256:36–45

Gómez-Aparicio L, Zamora R, Gómez JM, Hódar JA, Castro J, Baraza E (2004) Applying plant facilitation to forest restoration: a meta-analysis of the use of shrubs as nurse plants. Ecol Appl 14:1128–1138

Gómez-Mendoza L, Arriaga L (2007) Modeling the effect of climate change on the distribution of oak and pine species of Mexico. Conserv Biol 21:1545–1555

Gómez-Mendoza L, Galicia L, Aguilar-Santelises R (2008) Functional types sensitivity to climate change in sierra Norte of Oaxaca, Mexico. Investi Geog 67:76–100

González-Espinosa M, Quintana-Ascencio PF, Ramírez-Marcial N, Gaytán-Guzmán P (1991) Secondary succession in disturbed Pinus-Quercus forests in the highlands of Chiapas, Mexico. J Veg Sci 2:351–360

González-Tagle MA, Schwendenmann L, Pérez JJ, Schulz R (2008) Forest structure and woody plant species composition along a fire chronosequence in mixed pine-oak forest in the Sierra Madre oriental, Northeast Mexico. Forest Ecol Manag 256:161–167

Heyerdahl EEK, Alvarado E (2003) Influence of climate and land use on historical surface fires in pine-oak forests, Sierra Madre occidental, Mexico. In: Veblen TT, Baker WL (eds) Fire and climatic change in temperate ecosystems of the Western Americas. Springer-Verlag, New York, pp 196–217

Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, Jones PG, Jarvis A (2005) Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol 25:1965–1978

INEGI (2014) Guía para la interpretación de cartografía Uso del suelo y vegetación Escala 1:250, 000: serie VI / Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. INEGI, México, p c2017

Keenan RJ, Reams GA, Achard F, de Freitas JV, Grainger A, Lindquist E (2015) Dynamics of global forest area: results from the FAO global Forest resources assessment 2015. Forest Ecol Manag 352:9–20

López-Barrera F, Newton A (2005) Edge type effect on germination of oak tree species in the highlands of Chiapas, Mexico. Forest Ecol Manag 217:67–79

López-Barrera F, Manson RH, González-Espinosa M, Newton AC (2006) Effects of the type of montane forest edge on oak seedling establishment along forest-edge-exterior gradients. Forest Ecol Manag 225:234–244

Margolis EQ, Woodhouse CA, Swetnam TW (2017) Drought, multi-seasonal climate, and wildfire in northern New Mexico. Clim Chang 142:433–446

Martínez-Vilalta J, Lloret F (2016) Drought-induced vegetation shifts in terrestrial ecosystems: the key role of regeneration dynamics. Glob Planet Chang 144:94–108

McCune B (1988) Ecological diversity in north American pines. Am J Bot 75:353–368

Melo FPL, Martnez-Salas E, Bentez-Malvido J, Ceballos G (2010) Forest fragmentation reduces recruitment of large-seeded tree species in a semi-deciduous tropical forest of southern Mexico. J Trop Ecol 26:35–43

Meunier J, Brown PM, Romme WH (2014) Tree recruitment in relation to climate and fire in northern Mexico. Ecology 95:197–209

Minnich RA, Barbour MG, Burk JH, Sosa-Ramírez J (2000) Californian mixed-conifer forests under unmanaged fire regimes in the sierra San Pedro Martir, Baja California, Mexico. J Biogeogr 27:105–129

Miranda F, Hernández-X E (1963) Los tipos de vegetación de México y su clasificación. Bol Soc Bot Méx 28:29–179

Montes-Hernández B, López-Barrera F (2013) Seedling establishment of Quercus insignis: a critically endangered oak tree species in southern Mexico. Forest Ecol Manag 310:927–934

Pérez P, López F, García OF, Cuevas-Reyes P (2013) Procesos de regeneración natural en bosques de encinos: factores facilitadores y limitantes. Revista DES Ciencias Biológico Agropecuarias Univ Michoacana San Nicolás Hidalgo 1:18–24

Pompa-García M, Camarero JJ, Rodríguez-Trejo DA, Vega-Nieva DJ (2018) Drought and spatiotemporal variability of forest fires across Mexico. Chin Geogr Sci 28:25–37

Prăvălie R (2018) Major perturbations in the Earth’s forest ecosystems. Possible implications for global warming. Earth-Sci Rev 185:544–571

Quintana-Ascencio PF, Ramírez-Marcial N, González-Espinosa M, Martínez-Icó M (2004) Sapling survival and growth of coniferous and broad-leaved trees in successional highland habitats in Mexico. Appl Veg Sci 7:81–88

Ramírez-Marcial N, González-Espinosa M, Williams-Linera G (2001) Anthropogenic disturbance and tree diversity in montane rain forests in Chiapas, Mexico. Forest Ecol Manag 154:311–326

Ramírez-Marcial N, Camacho-Cruz A, González-Espinosa M, López-Barrera F (2006) Establishment, survival and growth of tree seedlings under successional montane oak forests in Chiapas, Mexico. In: Kappelle M (ed) Ecology and conservation of neotropical montane oak forests. Springer, Berlin, pp 177–189

Retana J, Espelta JM, Habrouk A, Ordóñez JL, Solà-Morales F (2002) Regeneration patterns of three Mediterranean pines and forest changes after a large wildfire in NE Spain. Ecoscience 9:89–97

Rigling A, Bigler C, Eilmann B, Feldmeyer-Christe E, Gimmi U, Ginzler C, Graf U, Mayer P, Vacchiano G, Weber P, Wohlgemuth T, Zweifel R, Dobbertin M (2013) Driving factors of a vegetation shift from scots pine to pubescent oak in dry Alpine forests. Glob Chang Biol 19:229–240

Riitters K, Wickham J, Costanza JK, Vogt P (2016) A global evaluation of forest interior area dynamics using tree cover data from 2000 to 2012. Landsc Ecol 31:137–148

Rodrigo A, Picó X, Retana J (2004) Direct regeneration is not the only response of Mediterranean forests to intense fires. Ecology 85:716–729

Rodríguez-Trejo DA, Fulé PZ (2003) Fire ecology of Mexican pines and a fire management proposal. Int J Wildland Fire 12:23–37

Roncal-García S, Soto-Pinto L, Castellanos-Albores J, Ramírez-Marcial N, de Jong BHJ (2008) Sistemas agroforestales y almacenamiento de carbono en comunidades indígenas de Chiapas, México. Interciencia 33:200–206

Sáenz-Romero C, Rehfeldt GE, Crookston NL, Duval P, St-Amant R, Beaulieu J, Richardson BA (2010) Spline models of contemporary, 2030, 2060 and 2090 climates for Mexico and their use in understanding climate-change impacts on the vegetation. Clim Chang 102:595–623

Searle EB, Chen HYH (2017) Persistent and pervasive compositional shifts of western boreal forest plots in Canada. Glob Chang Biol 23:857–866

Segura G (2000) Mexico’s forests sector and policies: a general perspective. Constituting the commons: crafting sustainable commons in the new millennium, the eighth biennial conference of the International Association for the Study of common property, Bloomington, Indiana

Stambaugh MC, Muzika RM, Guyette RP (2002) Disturbance characteristics and overstory composition of an old-growth shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata Mill.) forest in the Ozark Highlands, Missouri, USA. Nat Areas J 22:108–119

Stambaugh MC, Creacy G, Sparks J, Rooney M (2017) Three centuries of fire and forest vegetation transitions preceding Texas’ most destructive wildfire: lost pines or lost oaks? Forest Ecol Manag 396:91–101

Stephens SL, Gill SJ (2005) Forest structure and mortality in an old-growth Jeffrey pine-mixed conifer forest in North-Western Mexico. Forest Ecol Manag 205:15–28

Swaine MD, Whitmore TC (1988) On the definition of ecological species groups in tropical rain forests. Vegetatio 75:81–86

Valencia-A S (2004) Diversidad del género Quercus (Fagaceae) en México. Bol Soc Bot Méx 75:33–53

Valencia-A S, Gual-Díaz M (2014) La familia Fagaceae en el bosque mesófilo de montaña de México. Bot Sci 92:193–204

van Zonneveld M, Jarvis A, Dvorak W, Lema G, Leibing C (2009) Climate change impact predictions on Pinus patula and Pinus tecunumanii populations in Mexico and Central America. Forest Ecol Manag 257:1566–1576

Vayreda J, Gracia M, Martinez-Vilalta J, Retana J (2013) Patterns and drivers of regeneration of tree species in forests of peninsular Spain. J Biogeogr 40:1252–1265

Vayreda J, Martinez-Vilalta J, Gracia M, Canadell JG, Retana J (2016) Anthropogenic-driven rapid shifts in tree distribution lead to increased dominance of broadleaf species. Glob Chang Biol 22:3984–3995

Wahlenberg WG, Greene SW, Reed HR (1939) Effects of fire and cattle grazing of longleaf pine lands as studied at McNeill Mississippi. Technical Bulletin 683, US Department of Agriculture, Washington D.C., p 52

Woodward FI, Lomas MR, Kelly CK (2004) Global climate and the distribution of plant biomes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci 359:1465–1476

Works MA, Hadley KS (2004) The cultural context of forest degradation in adjacent Purepechan communities, Michoacan, Mexico. Geogr J 170:22–38

Zhang T, Niinemets Ü, Sheffield J, Lichstein JW (2018) Shifts in tree functional composition amplify the response of forest biomass to climate. Nature 556:99–102

Acknowledgements

We thank Ricard Arasa-Gisbert and Jordi Vayreda for help in restructuring and querying the original INFyS database.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by “‘Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología - CONACYT’“ by a national research grant/scholarship (CVU 225254) to TAR and by the Spanish government through grant CGL2013–46808-R. JMV benefits from an ICREA Academia award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TA, JR and JMV conceived the study and planned the work. TA prepared the dataset and lead data analysis and manuscript writing with active participation from JR and JMV. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Alfaro Reyna, T., Martínez-Vilalta, J. & Retana, J. Regeneration patterns in Mexican pine-oak forests. For. Ecosyst. 6, 50 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-019-0209-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-019-0209-8