Abstract

Background

Nearly 55 percent of patients are said to be affected by the neurological effects of COVID-19. COVID-19 was shown to be related with stroke in 0.9 to 5% of people. It's critical to assess the impact of COVID-19 on the outcomes of acute ischemic stroke. The goal of this study was to look at the outcomes and characteristics of patients who had an acute ischemic stroke due to covid-19 infection.

Results

The participants in this study were 399 people who had had a stroke. COVID-19 positivity was confirmed in 77 cases, while COVID-19 negativity was confirmed in 322. In the COVID-19 and control groups, the average age of the patients was 65.4 ± 10.2 and 65.3 ± 11.8, respectively. The Covid-19 and control groups had a mean stroke onset of 5.2 ± 2.1 and 5.7 ± 3.8 h, respectively (P = 0.12). There was a high in-hospital mortality rate among patients with COVID-19 with a rate of 11.7% compared to 4.04% among the control group (P = 0.02). At discharge, the number of patients with mRS > 2 was higher (P = 0.001) among the COVID-19. There was a correlation between the mean levels of D-Dimer (r = 0.668, P < 0.001), the severity of COVID-19 (r = 0.802, P < 0.001), and mRS > 2.

Conclusion

Despite receiving equal acute care as non-COVID-19 patients, COVID-19 patients had more severe strokes and had worse outcomes. This includes a high chance of death while in the hospital as well as a significant level of disability. Neurologists should use timely and effective therapies, particularly for patients who are at a higher risk of having a stroke. This includes elderly patients, patients with severe COVID-19, patients with high levels of D-Dimer, and those with high NIHSS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

COVID-19 is a novel strain of the -coronavirus family that is enclosed, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus. COVID-19 has become a prominent source of illness and mortality worldwide since its emergence in December 2019. The WHO labelled the disease a pandemic in March 2020 [1]. More than 175 million people have been infected with COVID-19 in the year since this date. More than four million people died as a result of the contagiousness, making it the most serious health disaster since the influenza pandemic [2, 3]. According to preliminary estimates, the Middle East accounted for more than 3% of all COVID-19-related death cases worldwide [4,5,6]. By December 2021, Egypt had confirmed over 380,000 COVID-19 cases, contributing to an estimated $1 billion in revenue, contributing to approximately 21,000 deaths [7].

The respiratory system is most affected by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). Extrapulmonary symptoms like cardiac failure, renal insufficiency, and neurological problems affect a considerable proportion of SARS-CoV-2 patients. Nearly 55 percent of patients are said to be affected by the neurological effects of COVID-19. COVID-19 was shown to be related with stroke in 0.9 to 5% of people [8,9,10]. This could be related to systemic inflammation and cytokine storm, postinfectious immune-mediated reactions, and direct viral-induced endotheliopathy. With virus particles recovered from numerous tissues, including brain tissue, these diseases may lead to angiopathic thrombosis [11]. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors (ACE-2) are abundantly presented within different organs' endothelial and epithelial cells. COVID-19 infection downregulates the expression of these receptors, resulting in a marked increase in blood pressure, volume overload, and progressive hypoxemia [12, 13].

Stroke is linked to a higher rate of mortality in the hospital. Furthermore, it has a significant negative impact on the patient's life and is linked to disability, psychological distress, and a lack of social interactions [14, 15]. It is critical to assess the impact of COVID-19 on the outcomes of acute ischemic stroke. Recognizing such evidence may aid neurologists in better understanding how COVID-19 may affect stroke patients and, as a result, more effectively utilize the most effective therapies for stroke patients. However, there is a scarcity of evidence in the literature. This is due to a dearth of well-structured clinical research, as well as differences in populations, sample bias, heterogeneity, study objectives, and follow-up periods.

These limitations result in controversial results, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions from the available evidence. Therefore, the current study aimed to assess the outcome and characteristics of patients with acute ischemic stroke associated with covid-19 infection.

Methods

This prospective cohort multicentric study involved 399 patients presented with acute stroke patients diagnosed according to WHO criteria [16]. Patients with or without a diagnosis of COVID-19 infection admitted to our hospitals, during the period from March 2020 to September 2021 were included. Patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage or patients with transient ischemic attack were excluded.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

After obtaining approval from the local ethics committee, patients who agreed to participate gave their signed informed consent after explanation of the trial benefits and hazards. All procedures were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

The patients were then divided into two groups. Within four days of admission, the COVID-19 group had a positive nasal SARS-CoV-2 PCR test. Patients who had clinical characteristics indicative of COVID-19 at the time of admission and were determined to be SARS-CoV-2 positive at any point during the first ten days of hospitalization were also included in the study. Patients who were consistently SARS-CoV-2 negative or who were never tested because they did not develop symptoms or evidence of COVID-19 made up the other group. The study excluded patients with traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, subdural hematoma, and extradural hematoma.

Demographic data, risk factors, stroke characteristics, management, and stroke severity (assessed using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] score) were recorded. For ischaemic strokes. The TOAST (Trial of ORG 10172 in acute stroke treatment) classification was either taken from the discharge summary or was inferred from the clinical team’s documented assessment of likely stroke aetiology [17]. Stroke territory and revascularization procedures were gathered. The time elapsed between stroke and SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis, treatment received, chest computed tomography (CT), and laboratory data were recorded. The in-hospital complications and disability on discharge were determined using the modified Rankin Scale (mRS), which varies from 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (death) [18].

Statistical analysis

The student's T-test was used to compare continuous normally distributed data in the form of mean and standard deviation (SD). The median and range were used to describe non-normally distributed data, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare between the case and control groups. Categorical variables were reported as a number or a percentage, and groups were compared using Pearson's chi-square test and Fisher's exact test. For non-parametric variables, Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was used to do correlation analysis. The binary logistic regression model was used to determine factors linked to stroke outcomes in COVID-19 patients. The significance is established when two-sides P-value < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 25 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, New York, USA), [19].

Results

A total of 417 stroke patients were admitted to the emergency department during the study period. Out of them, 77 patients were confirmed SARS-CoV-2 positive (COVID-19 group), and 322 patients were SARS-CoV-2 negative (control group), while 18 patients were excluded from the study. The mean age of the included patients was 65.4 ± 10.2 and 65.3 ± 11.8 in the COVID-19 and control groups, respectively. There were 45 (58.4%) males in the COVID-19 group and 195 (60.6%) males in the control group. Patients with COVID-19 had higher mean levels of total leucocytic count (TLC) (P < 0.001), platelet count (P < 0.001), and C-reactive protein (CRP) ((P < 0.001), in comparison to the control group. There was a statistically significant low mean of total lymphocytic count among COVID-19 group, in comparison to the control group with a mean of 0.86 ± 0.12 and 1.33 ± 0.28, respectively (P < 0.0001). There was no difference between age, gender, and comorbidities between both groups (Table 1).

Regarding Stroke characteristics and treatment, the mean stroke onset was 5.7 ± 3.8 and 5.2 ± 2.1 h among the Covid-19 and control groups (P = 0.12). On admission, 42 (54.5%) patients were treated with antiplatelets among the Covid-19 group, relative to 174 (54%) patients within the control group (P = 0.94). Furthermore, 12(15.6%) and 59(18.3%) patients received Alteplase among the Covid-19 and control groups (P = 0.62), respectively. The most frequently affected territory was the anterior circulation, affecting 46 (59.74%) and 218 (67.7%) patients within the Covid-19 and the control groups (P = 0.52). The cause of the stroke was large vessel occlusion in 21(27.3%) patients within the Covid-19 group and 68(21.1%) patients within the control group (P = 0.69). although percentage of patients with fits in Covid-19 cases was higher than control group yet P value was non-significant (0.07) (Table 2).

Concerning the impact of COVID-19 on the stroke outcomes, there was no significant difference in disease severity between the COVID-19 and control groups at admission (P = 0.906). Within the COVID-19 and control groups, the median NIHSS was 7 (0–42) and 12 (1–42), respectively. Patients with COVID-19 had a higher in-hospital death rate of 11.7 percent compared to 4.04 percent in the control group (P = 0.02). The most common cause of death in the Covid-19 group was respiratory failure and pulmonary embolism, accounting for 4 (5.19%) and 3 (3.89%) patients, respectively. At discharge, the number of patients with mRS > 2 was statistically substantially greater (P = 0.001) in the COVID-19 group, with 50 (64.93%) patients compared to 133 (41.3%) patients in the control group (Table 3).

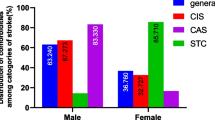

As for Predictors of stroke outcomes in COVID-19 Patients, the age of the patients and mRS > 2 had a positive connection (r = 0.227, P = 0.047). There was an association between mean D-Dimer levels (r = 0.668, P = 0.001), COVID-19 severity (r = 0.802, P = 0.001), NIHSS (r = 0.826, P = 0.001), and mRS > 2 in this regard. Neither the NIHSS (P = 0.966) nor the severity of COVID-19 (P = 0.978) were significant predictors of mRS > 2 at discharge in the binary logistic regression model (Tables 4, 5 and Fig. 1).

Discussion

The present COVID-19 situation has highlighted the importance of determining the pandemic's impact on healthcare [20]. While several research have looked at the relation between COVID-19 and neurological symptoms, the influence of the present pandemic on stroke outcomes has to be looked into more. This is because variances in the investigated population, healthcare services, and study technique make it difficult to draw a final conclusion from the existing literature [21, 22]. As a result, the current prospective study was carried out to evaluate the short-term outcomes of stroke in Egyptian patients diagnosed with COVID-19 and to identify potential determinants of stroke outcomes in the short-term.

COVID-19 patients experienced poor stroke outcomes, according to the current study. In patients with COVID-19, the in-hospital death rate was around three times that of the control group. At patients discharge, most COVID-19 patients had poor stroke outcomes, with a risk of roughly 1.5 times that of COVID-19 patients. Furthermore, patients who were elderly, had severe COVID-19, had high levels of D-Dimer, or had a high NIHSS had a higher chance of bad stroke outcomes at discharge. In the binary regression model, however, neither of these characteristics was significantly linked with mRS > 2. COVID-19 has been linked to the onset of ischemic stroke via thrombotic and inflammatory processes [23, 24].

The development of a cytokine storm and activation of the innate immune system, embolic events propagated by pre-existing or new-onset arrhythmias, and hypoxia-induced ischemia secondary to severe pulmonary illness are among the primary hypothesized processes. These conditions exacerbate the effects of stroke, resulting in additional neurological impairments and, as a result, poor outcomes. These findings matched those of Mart-Fàbregas and colleagues, published in 2021. They discovered that patients who had an ischemic stroke linked to COVID-19 had a more severe stroke. In comparison to patients without COVID-19, they reported a 3.1-fold increase in mortality risk within 72 h of admission [25]. The significant in-hospital death rate linked with COVID-19 is due to the concomitant respiratory distress and multiorgan failure, in addition to the already weakened general state due to the stroke.

This finding can help epidemiologists and doctors treating stroke on the front lines, especially in places where COVID-19 prevalence is high [24]. COVID-19 plays a varied role in stroke risk depending on the severity of the illness. Patients with more serious conditions are more likely to have a stroke and have poorer results. The fact that stroke occurred in 5.7 percent of patients with critical illness compared to 0.8 percent of individuals with milder COVID-19 condition backs up this claim [25]. In hospitalized patients with severe disease during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China, a retrospective analysis found an incidence of acute ischemic stroke of about 5% [26]. Our main concern since the introduction of COVID-19 in Egypt has been to maintain the same level of efficiency in the acute stroke service.

According to the findings of the current study, some stroke victims avoided obtaining emergency care in hospitals for fear of infection. This explains why there are fewer hospitalized stroke patients and a higher NIHSS score, which indicates a severe stroke. Patients having mild strokes during the COVID phase may be less likely to seek medical care [27, 28]. Roushdy and colleagues in 2020 studied 93 Egyptian patients with acute ischemic stroke. They found that concern of contracting COVID-19 and a lack of healthcare resources prevented 11 percent of patients from receiving prompt stroke treatment [29]. In this regard, Aref and colleagues in 2021 reported that in the COVID-19 era, fear of infection and lockdown issues were the most common causes of delayed arrival in ischemic stroke [30].

When compared to earlier findings on stroke in COVID-19 patients, the new study had several advantages. It was based on a multicenter hospital registry to begin with. COVID-19 patients' outcomes were compared to non-COVID-19 patients who had an acute stroke and were treated with the same management procedures. These protocols should be tailored to the new in-hospital pathways created to prevent pandemic viral spread. Other investigations, like as chest CT, had an impact on stroke care time metrics in all patients admitted during the pandemic. The current study, on the other hand, has some drawbacks. To begin with, a variety of circumstances could have influenced whether patients sought emergency medical attention, were admitted to a hospital, and received extensive treatment. Some COVID-19 and ischemic stroke patients may have died before reaching the hospital, while others with lesser symptoms or treatment limits may have remained at home. This could have resulted in an underestimation of the total rate of ischemic stroke in COVID-19 patients. In addition, data from a registry set up to detect cardiac and thromboembolic problems in COVID-19 patients was used in part of our retrospective investigation.

Conclusion

Despite receiving equal acute care as non-COVID-19 patients, COVID-19 patients had more severe strokes and had worse outcomes. This includes a high chance of death while in the hospital as well as a significant level of disability. Neurologists should use timely and effective therapies, particularly for patients who are at a higher risk of having a stroke. This includes elderly patients, patients with severe COVID-19, patients with high levels of D-Dimer, and those with high NIHSS. Further studies with adequate sample size and a more extended follow-up period are required to tackle the current study's limitations.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are not publicly available as the participants requested that, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACE-2:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors

- mRS:

-

Modified Rankin Scale

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- TLC:

-

Total leucocytic count

- CRP:

-

C-Reactive protein

- NIHSS:

-

The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

References

World Health Organization. Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations 2005 Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

Ritchie H, Mathieu E, Rodés-Guirao L, Appel C, Giattino C, Ortiz-Ospina E, et al. Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus [Online Resource]; 2020.

Cascella M, Rajnik M, Aleem A, Dulebohn SC, Di Napoli R. Features, Evaluation, and Treatment of Coronavirus (COVID-19) [Updated 2022 May 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J of autoimm. 2020;109: 102433.

Younis NK, Rahm M, Bitar F, Arabi M. COVID-19 in the MENA region: facts and findings. J of Infec in Develop Count. 2021;15(3):342–9.

Gebhard C, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Neuhauser HK, Morgan R, Klein SL. Impact of sex and gender on COVID-19 outcomes in Europe. Biol of sex differ. 2020;11(1):1–13.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard Global Situation. 2021.

Romero-Sánchez CM, Díaz-Maroto I, Fernández-Díaz E, Sánchez-Larsen Á, Layos-Romero A, García-García J, et al. Neurologic manifestations in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: the ALBACOVID registry. Neurol. 2020;95(8):e1060–70.

Yaghi S, Ishida K, Torres J, Mac Grory B, Raz E, Humbert K, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and stroke in a New York healthcare system. Stroke. 2020;51(7):2002–11.

Spence JD, De Freitas GR, Pettigrew LC, Ay H, Liebeskind DS, Kase CS, et al. Mechanisms of stroke in COVID-19. Cerebrovas Disea. 2020;49(4):451–8.

Hoyer C, Ebert A, Huttner HB, Puetz V, Kallmünzer B, Barlinn K, et al. Acute stroke in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: a multicenter study. Stroke. 2020;51(7):2224–7.

Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Liu H, Wu Y, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. The Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):475–81.

Roushdy T, Hamid E. A review on SARS-CoV-2 and stroke pathogenesis and outcome. The Egypt J of Neurol, Psychiatry and Neurosurg. 2021;57(1):1–6.

Aho K, Harmsen P, Hatano S, Marquardsen J, Smirnov VE, Strasser T. Cerebrovascular disease in the community: results of a WHO collaborative study. Bull World Health Organ. 1980;58(1):113.

Hess DC, Eldahshan W, Rutkowski E. COVID-19-related stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2020;11(3):322–5.

Adams HP Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, Biller J, Love BB, Gordon DL, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in acute stroke treatment. Stroke. 1993;24(1):35–41.

Van Swieten J, Koudstaal P, Visser M, Schouten H, Van Gijn J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke. 1988;19(5):604–7.

Burn J. Reliability of the modified Rankin Scale. Stroke. 1992;23(3):438–9.

Stehlik-Barry K, Babinec AJ. Data analysis with IBM SPSS statistics. Birmingham: Packt Publishing Ltd; 2017.

Yıldırım S, Yildirim DC, Calıskan H. The influence of health on economic growth from the perspective of sustainable development: a case of OECD countries. World J Entrep Manag Sustain Dev. 2020;16(3):181–94.

Siow I, Lee KS, Zhang JJ, Saffari SE, Ng A, Young B. Stroke as a neurological complication of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of incidence, outcomes and predictors. J Stroke Cerebrov Dis. 2021;30(3): 105549.

Nannoni S, de Groot R, Bell S, Markus HS. Stroke in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J of Stroke. 2021;16(2):137–49.

Mohamud AY, Griffith B, Rehman M, Miller D, Chebl A, Patel SC, et al. Intraluminal carotid artery thrombus in COVID-19: another danger of cytokine storm? Am J of Neuroradiol. 2020;41(9):1677–82.

Martí-Fàbregas J, Guisado-Alonso D, Delgado-Mederos R, Martínez-Domeño A, Prats-Sánchez L, Guasch-Jiménez M, et al. Impact of COVID-19 infection on the outcome of patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2021;52(12):3908–17.

Fridman S, Bullrich MB, Jimenez-Ruiz A, Costantini P, Shah P, Just C, et al. Stroke risk, phenotypes, and death in COVID-19: systematic review and newly reported cases. Neurol. 2020;95(24):e3373–85.

Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan. China JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(6):683–90.

Li Y, Li M, Wang M, Zhou Y, Chang J, Xian Y, et al. Acute cerebrovascular disease following COVID-19: a single center, retrospective, observational study. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2020;5(3):279–84.

Aguiar Sousa D de, van der Worp H, Caso V, Cordonnier C, Strbian D, Ntaios G, et al. European Stroke Organisation. Maintaining stroke care in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from an international survey of stroke professionals and practice recommendations from the European Stroke Organisation. Eur Stroke J. 2020;5:230–6.

Roushdy TM, El Nahas NM, Aref HM, Georgy SS, Zaki AS, Bedros RY, et al. Stroke in the time of COVID-19 experience in two university stroke centers in Egypt. Available at SSRN 3588565. 2020.

Aref HM, Shokri H, Roushdy TM, Fathalla F, El Nahas NM. Pre-hospital causes for delayed arrival in acute ischemic stroke before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study at two stroke centers in Egypt. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(7): e0254228.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was self-funded by the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AHE participated in hypothesis generating, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript writing. HAE proposed the idea, tested the hypothesis, and revised the extracted data, data analysis and manuscript. MAS participated in hypothesis generating, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript writing. `All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in concordance with declaration of Helsinki and each participant signed a written informed consent before being enrolled in the study. The institutional review board (IRB)approval was obtained from the ethical committee of Faculty of Medicine for boys, Al-Azhar University, Cairo on 14th April, 2021. There was no reference number provided by our IRB.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elsheshiny, A.H., El Gharieb, H.A. & Sabrh, M.A. Outcome and characteristics of COVID-19 patients associated with stroke: a multicenter hospital-based study in Egypt. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg 58, 81 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-022-00517-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-022-00517-2