Abstract

Background

While teleost fishes represent two thirds of marine vertebrates, the role of their external microbiota in relationship with their environment remains poorly studied, especially in wild populations. Hence, the interaction of their microbiota with ectoparasites is largely unknown. Microbiota can act as a protective barrier against pathogens, and/or be involved in host recognition by parasites. Thus, host-parasite associations should now be considered as a tripartite interplay where the microbiota shapes the host phenotype and its relation to parasites. Monogeneans (Platyhelminthes) are direct life cycle ectoparasites commonly found on teleost skin and gills. The role of bacterial communities within skin and gill mucus which either pre-exist monogeneans infestation or follow it remain unclear. This is investigated in this study using the association between Sparidae (Teleostei) and their specific monogenean ectoparasites of the Lamellodiscus genus. We are exploring specificity mechanisms through the characterization of the external mucus microbiota of two wild sparid species using 16s rRNA amplicon sequencing. We investigated how these bacterial communities are related to constrated Lamellodiscus monogeneans parasitic load.

Results

Our results revealed that the increase in Lamellodiscus load is linked to an increase in bacterial diversity in the skin mucus of D. annularis specimens. The date of capture of D. annularis individuals appears to influence the Lamellodiscus load. Correlations between the abundance of bacterial taxa and Lamellodiscus load were found in gill mucus of both species. Abundance of Flavobacteriaceae family was strongly correlated with the Lamellodiscus load in gill mucus of both species, as well as the potentially pathogenic bacterial genus Tenacibaculum in D. annularis gill mucus. Negative correlations were observed between Lamellodiscus load and the abundance in Vibrionaceae in gill mucus of D. annularis, and the abundance in Fusobacteria in gill mucus of P. acarne specimens, suggesting potential applications of these bacteria in mitigating parasitic infections in fish.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight the dynamic nature of fish microbiota, in particular in relation with monogeneans infestations in two wild sparid species. More generally, this study emphasizes the links between hosts, bacterial communities and parasites, spanning from the dynamics of co-infection to the potential protective role of the host’s microbiota.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Any organism is likely to host one or more parasitic species during its lifetime [1]. However, this does not mean that all hosts are equal face to parasitism: variability can be observed in the probability of infection (prevalence) and in the number of parasites within each host (parasitic load). Recently, among the avenues explored to explain these variations in host specificity, an increasing number of studies [2,3,4] suggest a role of the microbiota in host-parasite interactions. Indeed, several studies have shown that parasitized hosts possess a specific microbiota that differs from non-parasitized hosts, emphasizing the putative involvement of the microbiota in host-parasite interactions [5,6,7,8,9]. However, it remains unclear whether some of these differences in host bacterial communities are a cause or a consequence of parasitic infections.

Certain bacteria have been shown to protect the host against parasitic infections. This is the case, for example, in bumblebees, where several studies have shown a protective effect of the gut microbiota against a trypanosomatid parasite [10, 11]. Conversely, bacteria pre-existing the infection could favor the establishment and survival of parasite by creating favorable conditions. In 2010, Hayes et al. [12] showed that reducing the number of bacteria in the large intestine of mice significantly reduced the number of hatched nematode eggs. Other authors have shown that the microbiota can be involved in the attraction of parasites toward their host via chemical cues. This has for example been shown for mosquitos that are attracted by the skin microbiota of certain human hosts [13]. Another recent study has shown that cane toad skin secretions (i.e., substances produced by amphibians and their microbiota) attract lungworm larvae and enhance their infection success [14]. Interestingly, these authors showed that, depending on the geographical area, these same skin secretions could also reduce the longevity and infection success of the parasite larvae.

Differences in bacterial communities also seems to be the result of parasite infestation. In the case of helminth infestation, it has been shown that parasites induce a change in the composition of the microbiota [15], reducing airway inflammation in mice to prevent their expulsion, and that this mechanism is suppressed in hosts that have received antibiotics [16, 17]. A recent study suggest that infection by a crustacean ectoparasite (Tracheliastes polycolpus) induced a shift of the fin microbiota in a freshwater fish (Leuciscus burdigalensis), and this shift was restricted to the fin where the parasite anchored [18]. Thus, microbiota has been shown to reflect the infection status of the host [3].

Deciphering the role of the microbiota in parasitic infection can be pertinent in fields such as aquaculture, where parasites are responsible for considerable annual economic losses [19]. This is the case for monogeneans [20], ectoparasites abundant on teleost skin and gills. Teleost skin and gills are covered with a mucus colonized by stable communities of microorganisms that form the external microbiota. Several studies have shown that monogeneans detect their hosts via cues emitted by fish mucus [21,22,23,24] such as mucosal macromolecules (IgM) [25] and glycoproteins [26, 27]. Recent work suggests that the molecules involved in the monogeneans’ host recognition system are produced by the host microbiota [28]. Among the many roles assumed by the microbiota for its host fish [29,30,31], its link with pathogens and parasites is not well understood. One of the difficulties is to disentangle causes from consequences, particularly in wild populations where the microbiota is under the influence of numerous biotic and abiotic factors [32,33,34,35].

In the Mediterranean Sea, the association between the Sparidae (Perciformes) fish family and their specific monogeneans belonging to the Lamellodiscus genus is a relevant model to study fish-monogenean association. Lamellodiscus monogeneans are ectoparasites with a direct life cycle often abundant on the skin and gills of sparids. The establishment of monogeneans on their host is regulated at multiple levels, involving two critical stages: when the swimming larvae (oncomiracidia) seek out, reach and attach on fish skin, and when the larvae move, attach and establish in the gills. Previous studies have shown that certain highly specific monogenean larvae are able to parasitize fish species not recorded as their host species [24, 36]. Ohhashi and coll. [24] have proposed that these monogenean larvae could only survive for a few days and finally detach from their non-specific host, being unable to mature to the adult stage in the gills.

The aim of this study was to characterize the differences in bacterial communities patterns in the external mucus (skin and gill) of two Mediterranean sparid species (Diplodus annularis and Pagellus acarne) with contrasting Lamellodiscus monogeneans parasitic loads. Lamellodiscus abundance and diversity were assessed to investigate their effect on the structure and diversity of bacterial communities in each individual’s external microbiota (i.e., the skin and gill mucus). The effect of sampling conditions (i.e., location and date of capture) on these two microbiota was also investigated. We focused our analysis on gill microbiota, where the parasites settle definitively as adults, to look for correlations between the abundance of a given bacterial taxa and Lamellodiscus abundance in both sparid species.

Materials and methods

Fish sampling, DNA extraction, 16s RNA sequencing and processing

Details of the protocols for fish sampling, DNA extraction, 16S rRNA sequencing and sequence processing protocols can be found in [35]. Briefly, fish sampling of D. annularis individuals was conducted in June and July 2021 in the bay of Banyuls-sur-Mer and fish sampling of P. acarne individuals was conducted in June, July 2021 and March 2022 in both bays of Banyuls-sur-Mer and Argelès-sur-Mer (northwestern Mediterranean Sea, France) (Supplementary table S1). All fish were collected from a net with gloves and immediately taken to the laboratory for dissection; skin mucus and gill mucus were collected with sterile spatula and immediately placed in sterile tubes and either frozen at -80 °C until DNA extraction. For convenience, we will refer to gills and skin in this study as “tissues”. A total of 28 fish individuals were sampled for their skin and gill mucus, all belonging to two sparid species: 12 individuals identified as Diplodus annularis and 16 individuals as Pagellus acarne (Table 1). For each fish sampling done in Banyuls-sur-Mer (4 sampling dates), two liters of seawater were collected in a sterile container and filtered through a 0.2 μm nitrocellulose filter which was stored at -80 °C prior to DNA extraction.

DNA was extracted by using the Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe MiniPrep Kit (Zymo Research, Orange, California). PCR amplification was carried out in triplicate and performed using primers targeting the hypervariable V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene: 341 F (5’CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′) and 805R (5′-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′) [37, 38]. A second PCR was performed to add barcodes to each amplified sample and the Illumina adapters. The concentration of all PCR products was normalized with a 96 well SequalPrep Normalization Plate (Thermofisher, France). Amplicons were sequenced using Illumina 2 × 300 bp MiSeq sequencing (FASTERIS SA, Switzerland).

The analysis of the raw sequences was done using the QIIME2 software and the standard pipeline of DADA2 [39,40,41]. Raw reads were demultiplexed, quality checked and trimmed to remove primer regions, paired ends were assembled, chimeric sequences were discarded, and reads were denoised. DADA2 generate a list of Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). Sequences were aligned against the SILVA 138 reference database distributed by the Silva project [42, 43]. The MAFFT program was used to align the sequences and FastTree to build a phylogenetic tree. Based on the classification, ASVs matching “Archaea”, “Eukaryota” and “Unassigned” or represented by a single sequence in all samples were removed.

Characterization of gill parasites

To characterize Lamellodiscus species diversity and abundance, Lamellodiscus individuals were recovered from three outermost gill arches for each fish individual and counted under a dissecting microscope. In this study, we will consider the total Lamellodiscus load without considering their species affiliation. Based on our previous results [35, 44] we determined that the mean intensity of Lamellodiscus in D. annularis specimens caught during the same season as ours was 13 Lamellodiscus per 3 gill arches. In P. acarne specimens caught during same seasons than ours, the mean intensity of Lamellodiscus was 21 per 3 gill arches. Consequently, for downstream analyses, individuals of each fish species were grouped into two categories: those with Lamellodiscus spp. intensity below the previously reported mean in the three dissected gill arches were classified as ‘lightly parasitized’ (LP); those with higher Lamellodiscus spp. mean intensity were classified as ‘heavily parasitized’ (HP). For simplicity, we will use the terms “heavily” or “lightly” parasitized to refer specifically to the parasite loads in Lamellodiscus spp.

Data analyses

The influence of location and date of capture on Lamellodiscus abundance in the fish was assessed using a Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon rank sum test in R, supported by permutation tests for robustness. α-diversity measures were estimated with Faith’s phylogenetic and Shannon indexes using the dataset normalized to the total number of sequences per samples and the function transform_sample_count in the phyloseq R package [45]. We performed one-way ANOVA (or non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests when data were not normally distributed) to compare alpha diversity between tissues (i.e., skin mucus, gill mucus and water) and species. When the ANOVA (or Kruskal-Wallis test) rejected the null hypothesis, we computed pairwise comparisons between group levels using Tukey post hoc tests (or post hoc Conover-Iman (CI) test) with Benjamini-Hochberg correction to detect significant differences between groups. Linear models (LM) or generalized linear model (GLM) (depending on the normal distribution of the data) were performed for each species to identify which fish-related factors (i.e. tissue, parasitism) or environment-related factors (collection date and capture location for P. acarne samples) influence fish bacterial diversity (lme4 package : lm/glm/glm.nb(Diversity ~ Tissue * Parasitism * Collection date * Capture location). For modeling Faith’s phylogenetic diversity obtained from D. annularis samples, a negative binomial regression was used (as the variance is larger than the mean). A GLM with Gamma distribution was used for Shannon diversity in P. acarne samples. Correlations between Lamellodiscus parasitic load (i.e., total abundance) and gill mucus microbiota diversity (Faith’s and Shannon index) were computed and their significance assessed using Pearson’s correlation tests. Finally, the number of shared ASVs among gill mucus microbiota of LP and HP individuals from both fish species and surrounding water was calculated and represented using a Venn diagram [46] using a rarefied dataset (rarefaction performed to the minimum library size of D. annularis samples, 5691 reads).

Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) using both Bray-Curtis, based on ASVs’ abundance, and weighted Unifrac distance, which takes into account both the ASVs’ abundance and their phylogenetic relationships, was used to assess the differences between the microbiota of the different fish species. Firstly, permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA (function adonis, vegan R package) and pairwise comparisons for Bray-Curtis and Weighted Unifrac indices (10,000 permutations) were used to to test for differences of PCoA groups between tissues (i.e., gill mucus, skin mucus and water) and species. For each tissue and species, we have performed additional multifactorial PERMANOVAs and used the r2 value from PERMANOVA to estimate the relative effect size (% of variation explained) of factors tested (date of capture, capture location, level of parasitism, and the interactions date of capture × capture location, date of capture × parasitism level, and capture location × parasitism level) on skin and gill microbiota of both species. Given that bacteria from the surrounding water could appear as transient bacteria on gill and skin mucus of fish, these analyses were also performed without considering sequences retrieved from water samples in D. annularis samples, for which surrounding water were available at each sampling date.

To assess how each bacterial taxon contributed to the dissimilarity between HP and LP gill or skin mucus bacterial communities, we performed a Linear discriminant analysis Effect Size (LEfSe) [47]. LEfSe provides Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) scores for the bacteria taxa contributing the most to the differences between bacterial communities. We calculated relative abundances (i.e., total sum scaling) of bacterial taxa (i.e., phyla, class, order, family and genus) showing a significant contribution to the dissimilarity between HP and LP bacterial communities.

Spearman’s rank correlation was used to investigate the putative link between the abundance of Lamellodiscus spp. and the composition of gill and skin bacterial communities at family and genus taxonomic level. A correlation between the abundance of a Lamellodiscus spp. and the abundance of a bacterial taxa was considered to be significant when p-value < 0.05. Only taxa with abundance > 5% and present in at least 2 samples were considered.

Results

For this study, 12 individuals belonging to Diplodus annularis species were sampled between June and July 2021. Between 0 and 90 Lamellodiscus spp. were found in the 3 dissected gill arches depending on the fish individual; 6 were classified as “lightly parasitized” (LP) and the other 6 were classified as “heavily parasitized” (HP). We also collected 16 Pagellus acarne individuals between June 2021 and March 2022. We found between 0 and 189 Lamellodiscus individuals in the 3 dissected gill arches, 8 fish individuals were classified as LP and the 8 remaining as HP (Supplementary Table S1). In total, 511 721 sequences assigned to bacteria binned into 4299 ASVs were retrieved from 56 fish samples and 4 water samples.

General patterns of bacterial composition

For the two fish species, the predominant bacterial phylum in gill and skin microbiota was Proteobacteria (67.74 ± 14.48% in relative abundance (i.e., total sum scaling method) in gill of D. annularis, 51.93 ± 22.39% for skin of D. annularis, 69.05 ± 20.74% for gills of P. acarne and 51.07 ± 16.92% for skin of P. acarne) (Fig. 1; Table 2). In D. annularis, the second most abundant phylum for gills was Verrumicrobiota (12.23 ± 15.70%) and Actinobacteria (12.53 ± 10.23%) for skin (Fig. 1; Table 2). Bacteroidota was the third most abundant phylum for both tissue in this species (9.15 ± 12.26% for gills and 12.14 ± 9.58% for skin) (Fig. 1; Table 2). In P. acarne, Bacteroidota was the second most abundant phylum found on the gills (8.30 ± 8.93%) and the skin (16.76 ± 9.39%) and Firmicutes the third most abundant in both tissues (6.85 ± 15.02% in gill and 9.28 ± 7.48% in skin) (Fig. 1; Table 2).

Figure 1: Relative abundance of bacterial phyla within lightly parasitized (LP) and heavily parasitized (HP) gill mucus or skin mucus of Diplodus annularis and Pagellus acarne.

Bacterial diversity of gill mucus and skin mucus

Two alpha diversity metrics were used to measure diversity within communities: the Faith’s phylogenetic index (phylogenetic richness) and the Shannon diversity index (taxonomic richness and evenness). When comparing diversity metrics, we found significant differences between the bacterial community of the P. acarne skin mucus, gill mucus and the surrounding water with both statistical tests (ANOVA; KW test, p < 0.05). This results from a highest bacterial diversity in skin mucus (Supplementary figure S1) but for both alpha diversity metrics, there was no significant differences in diversity between water and gill mucus (ANOVA; KW test, p < 0.05; CI tests, p > alpha/2 = 0.025, Post hoc Tukey p < 0.05) (Supplementary figure S1). In D. annularis, significant differences between bacterial communities in skin mucus, gill mucus and water were found only when considering the Faith index (KW test, p < 0.05) also explained by higher bacterial diversity in skin mucus (Supplementary figure S1).

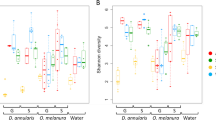

When considering only fish samples, the LM and GLM results showed that, for both species, tissue (i.e., gill mucus and skin mucus) significantly influences Shannon diversity (Supplementary Table S2). HP and LP P. acarne bacterial communities were significantly different from each other when considering Faith’s index (LM, p < 0.05) with a higher bacterial diversity in HP individuals (Fig. 2). For D. annularis, collection date significantly influenced diversity when considering the Faith index (GLM, p < 0.05), with fish caught in July 2021 displaying a greater bacterial diversity (Fig. 2). In both species, no significant interaction between tissues and parasitism (i.e., HP vs LP) or collection date was found, regardless the diversity index considered (LM or GLM, p > 0.05). For P. acarne, collection site significantly influenced Shannon diversity (GLM, p < 0.05) and a significant interaction between tissue and collection site was also observed (GLM, p < 0.05), meaning that the collection site impacts differently each external fish tissue. In addition, the date of collection seems to have an influence on the parasitic load in D. annularis individuals (Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon rank sum test, p < 0.01). On the contrary, place and date of capture did not significantly influence Lamellodiscus abundance (Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon rank sum test, p = 0.11, p = 0.83 respectively) in P. acarne individuals.

Factors explaining the dissimilarity of bacterial communities

To determine the factors explaining the variability between and within skin mucus, gill mucus and water microbiota, we used the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index (BC), and the weighted Unifrac distance (WU). Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was used to plot both BC and WU distances.

First, significant differences between bacterial communities from gill mucus, skin mucus and surrounding water were obtained when considering all samples together (PERMANOVA on BC and WU distances, p < 0.05, R2 = 0.10 and R2 = 0.15 respectively). An effect of host species within gill and skin mucus on bacterial communities based on BC dissimilarities can be observed (PERMANOVA on BC distances, p < 0.01, 0.07 < R²<0.09) (Table 3).

For each species and each tissue, additional PERMANOVAs were performed to identify factors that influence the composition of the external microbiota. Due to the relatively close sampling of Diplodus annularis individuals over time, no significant effect of collection date on the variability of gill mucus bacterial communities was found based on BC and WU dissimilarities (PERMANOVA, p > 0.05). However, a significant effect of collection date was found on skin mucus based on BC dissimilarities (PERMANOVA, p < 0.05, R2 = 0.16) (Table 3). Significant differences between bacterial communities from LP and HP D. annularis gill and skin mucus were found (PERMANOVA on BC and WU distances, p < 0.05; for BC distances R²=0.16, R²=0.24 respectively; for WU distances R²=0.41, R²=0.68) (Table 3, Supplementary figure S2). The same significant results were obtained without considering sequences from water samples in D. annularis samples, with a small decrease in influence of the level of parasitism on gill and skin mucus microbiota dissimilarities (PERMANOVA on BC and WU distances, p < 0.05, R2 = 0.15 and R2 = 0.34 respectively for HP and LP gill and R2 = 0.21 et R2 = 0.56 for skin mucus).

In P. acarne, sampling conditions had a significant effect on variability of bacterial communities in gill and skin mucus when considering BC dissimilarities. If we consider the differences of diversity between July 2021 and March 2022 (as a single individual was captured in June 2021), sampling date seems to have a stronger effect (PERMANOVA, p < 0.001, R²=0.19, R²=0.26 respectively) compared to the sampling location (PERMANOVA, p < 0.001, R²=0.11, R²=0.2) on gill and skin mucus bacterial communities (Table 3). A significant effect of the interaction between collection date and sampling location was found for gill and skin microbiota of P. acarne individuals (PERMANOVA, p < 0.05, R2 = 0.09 and R2 = 0.11 respectively) and a small effect of the interaction between sampling location and parasitism (i.e., LP or HP) for gill microbiota considering BC dissimilarities (PERMANOVA, p < 0.05, R2 = 0.07) (Table 3). When phylogenetic relationships between ASVs were taken into account (WU dissimilarities), no significant differences were found in the skin microbiota of P. acarne fish over time (p > 0.05) in contrast to the gills where sampling date seemed to have a strong significant effect on microbiota (p < 0.05, R²=0.71).

Moreover, P. acarne individuals captured at both sites harbor a closely related gill microbiota (PERMANOVA, WU dissimilarities p > 0.05) but a significative effect of the location was found on skin microbiota (p < 0.05, R²=0.37) (Table 3). In P. acarne, parasitism (i.e., LP or HP) does not seem to explain the dissimilarity of bacterial communities from skin mucus (PERMANOVA on BC and WU distances, p > 0.05). However, a significant difference was observed in gill microbiota only when WU distances were considered (PERMANOVA, p < 0.05, R²=0.12) (Table 3).

Gills of HP or LP D. annularis and HP or LP P. acarne harbor specific bacterial taxa (14.9%, 7.9%, 8.3%, 20.5% of ASVs respectively) (Fig. 3). These four compartments shared 2.5% of ASVs, mainly composed of Proteobacteria (Alpha and Gammaproteobacteria), followed by Bacteroidota as many Firmicutes as Cyanobacteria. The greatest compositional similarity was observed between LP and HP D. annularis (14.9%). It can be noted that LP individuals of both species share 118 ASVs (12.4%), of which 23 are shared solely between them, while HP individuals of both species share 91 ASVs (8.8%), of which 17 are shared solely between them (Fig. 3). 12.2% of ASVs are found only in water samples (corresponding to 55% of total ASVs retrieved from water samples) and are mainly composed by Proteobacteria (Alpha and Gammaproteobacteria) and Bacteroidota (Fig. 3).

Venn diagram representing representing percentage of shared ASVs between lightly parasitized (LP) P. acarne gill mucus (green), heavily parasitized (HP) P. acarne gill mucus (purple), LP D. annularis gill mucus (green), HP D. annularis gill mucus (yellow) and water (blue). PA = P. acarne, DA = D. annularis. Based on 0.005% abundance cutoff

Correlations between bacterial communities and parasitic load in gills

The microbiota diversity assessed using Faith phylogenetic index in the skin mucus of D. annularis was positively correlated with Lamellodiscus load (Pearson correlation test, p < 0.05, R = 0.885) (Supplementary figure S3). However, at gill level, no correlation was found between changes in parasite load and microbiota diversity for D. annularis or P. acarne (p > 0.05).

Then, we quantified how the relative abundance of bacterial taxa in gill mucus microbiota was related to parasite abundance. The abundance of all ASVs was aggregated to family or genus rank and then tested using Spearman’s rank correlation with the proportion of Lamellodiscus sp. found in the gills (parasitic load). The abundances of parasitic load of Lamellodiscus spp. displayed significant positive or negative correlations with the relative abundance of given bacterial taxa (Fig. 4). Significant differences in relative abundances of bacterial ASV among LP and HP fish were found (in both species and both tissues (linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe), Fig. 5).

Firstly, we observed that HP D. annularis gill microbiota was significantly more enriched in Bacteroidota (15.99% mean relative abundance (i.e., total sum scaling method) vs average of 2.32% in other LP fish) (LEfSe analysis, Fig. 5) and this proportion increased with parasite load in gill microbiota of both species (positive Spearman rank correlation, p = 0.001, ρ = 0.844 for D. annularis and p = 0.0132, ρ = 0.604 for P. acarne) (Fig. 4, Supplementary table S3). A medium positive correlation was found between the bacterial order Flavobacteriales, the bacterial family Flavobacteriaceae and the parasitic load of Lamellodiscus sp. in gills of P. acarne hosts (p = 0.021, ρ = 0.571 for both taxonomic rank) and a strong positive correlation in gills of D. annularis host (p = 0.001, ρ = 0.826; p = 0.003, ρ = 0.779) (Fig. 4, Supplementary table S3). In addition, this family was found in higher proportion in HP D. annularis gill microbiota (14.11% vs 1.28%) and HP P. acarne gill microbiota (9.99% vs 2.23%) (LEfSe analysis, Fig. 5).

The bacterial families Rhodobactereaceae and Puniceicoccaceae were positively correlated with the abundance of Lamellodiscus sp. in the gills of D. annularis (p = 0.001, ρ = 0.829 and p = 0.002, ρ = 0.803 respectively) as well as one unidentified Rhodobactereaceae genus in gill microbiota (p = 0.003, ρ = 0.769 respectively) of D. annularis (Fig. 4, Supplementary table S3).

In both tissues of D. annularis, a strong positive correlation was observed between parasitic load and the family Pseudoalteromonadaceae and more specifically with the genus Pseudoalteromonas (p = 0.001, ρ = 0.802 for both taxonomic rank in gill and p = 0.001, ρ = 0.811 for both taxonomic rank in skin) (Fig. 4, Supplementary table S3). Indeed, this bacterial family and genus were totally absent in gill microbiota of LP individuals (3.72% vs. 0% for both taxonomic rank) (LEfSe analysis, Fig. 5).

In contrast, the gill mucus microbiota of LP D. annularis contained significantly higher abundances of Vibrionaceae (32.9%), whereas this family was much less represented in other HP fish (9.95%) (LEfSe analysis, Fig. 5). These results were supported by strong negatives correlations between the abundance of Lamellodiscus sp. and the bacterial family Vibrionaceae or with the genus Photobacterium (p = 0.001, ρ=-0.890 and p = 0.028, ρ=-0.631 respectively) (Fig. 4, Supplementary table S3). Negative correlations were found with the genus Enterovibrio in gills (p = 0.016, ρ=-0.674) and skin (p = 0.038, ρ=-0.603) microbiota of D. annularis (Fig. 4, Supplementary table S3).

Another negative correlation was found between Lamellodiscus abundance and the Micrococcales order (p = 0.025, ρ =-0.638) and more specifically with the Microbacteriacea family (p = 0.011, ρ = -0.699) in D. annularis gills (Fig. 4, Supplementary table S3). In this family, the abundance of a non-identified genus is correlated with the parasitic load in both tissue of D. annularis (p = 0.007, ρ = -0.727 in gill and p = 0.05, ρ = -0.581 in skin) (Fig. 4, Supplementary table S3). This genus appears to be significantly more abundant in the gill microbiota of LP fish (LEfSe analysis, Fig. 5). The abundance of the genus Blastopirellula also decreased with parasitic load in D. annularis gill microbiota (p = 0.035, ρ = -0.609) (Fig. 4, Supplementary table S3).

In P. acarne individuals with low parasite load, gill microbiota appeared enriched with Fusobacteria (0.69% vs 0.05%), Fusobacteriaceae family (0.69% vs 0.05%) and Propionigenium genus, which is absent in HP gill microbiota (0.32% vs 0%) (LEfSe analysis, Fig. 5). A negative correlation was in particular observed for the family Fusobacteriaceae (Spearman’ rank order correlation, p = 0.048, ρ = -0.501) in P. acarne gill microbiota (Fig. 4, Supplementary table S3). A medium correlation between the parasitic load and the abundance of the family Saprospiraceae was found in the gills of P. acarne (p = 0.03, ρ = 0.54 and p = 0.002, ρ = 0.716 respectively) (Fig. 4, Supplementary table S3).

Discussion

In this study, we examined the associations between gill and skin mucus bacterial communities of two wild sparid species, D. annularis and P. acarne, with contrasting parasitic loads of Lamellodiscus monogeneans.

Regarding general trends, Proteobacteria largely dominates the external microbiota of all individuals, which is consistent with previous studies [33,34,35]. If some bacteria could appear only transiently in the external mucus microbiota, our analysis with D. annularis samples without considering sequences retrieved from water samples indicated that the majority of bacterial communities are not reflections of the microbial assemblage of the surrounding water but result from selective mechanisms, such as suggested by previous studies [33, 34, 44, 48]. In consequence, even though these comparisons could not be done with P. acarne samples in the present study, it is likely that external mucus of these individuals harbor their own bacterial communities that differ from surrounding water. For one of the species we detected a significant effect of sampling date and location on the external microbiota, suggesting that the microbiota is variable and dynamic, shaped by environmental conditions. Gill and skin mucus also contain tissue-specific and species-specific assemblages. These results are consistent with previous studies that shown that both environmental [49, 50] and host-associated factors shape fish microbiota [29, 34, 48, 51].

We identified differences in the diversity of the microbiota between LP and HP of P. acarne, with the HP mucus appearing to be richer and more diverse than the LP mucus. In D. annularis, we did not identified any differences in the diversity of the microbiota between HP and LP gill or skin mucus. However, we identified a positive correlation between parasitic load and microbiota diversity in skin mucus. This is not in line with the results of [35] who found that an increase of parasite diversity is linked to a decrease of gill microbiota diversity. Nevertheless, other studies highlighted that an increase in alpha diversity indices follows parasitic infestation. Llewellyn and coll. [52] showed that the experimental infection of Atlantic salmon with salmon lice resulted in an increased diversity of the skin microbiota in infected fish. Zhang and coll. [53] showed that a group of rainbow trout experimentally parasitized by Ichthyophthirius multifiliis presented higher values for alpha diversity in skin microbiota than a control group. Overall, these results suggest that the relation between parasites and diversity of the external microbiota greatly varies depending on the host and parasite species.

The effect of the sampling date on parasitic load is not the same depending on the host species considered. In the case of D. annularis, sampling date had a significant effect on the parasite load in Lamellodiscus, even though the sampling period was limited in time (2 summer months). In the case of P. acarne, sampling was carried out over two months in different seasons, but without any effect on the parasite load in Lamellodiscus. These results suggest that several factors are involved in the occurrence and abundance of monogeneans in fish, such as environmental factors like salinity [54] or water temperature [55, 56]. However, the effect of water temperature does not seem to be the same for all monogenean species. Some authors have shown that some Dactylogyrus species seem to prefer warm temperatures (D. vastator, D. ctenopharyngodonis) while others seem to prefer colder temperatures (D. lamellatus, D. extensus) [57, 58].

Using the analysis of bacterial communities, we identified bacterial families and genera that correlated positively or negatively with the parasite load in Lamellodiscus. We found a strong correlation between the abundance of Flavobacteriaceae and the parasite load in the gill mucus of both species. Similar results have already been reported: this family of bacteria is often found after a parasitic infection. For example, Zhang and coll. [53] showed that experimental infection with Ichthyophthirius multifiliis (ciliate) reduced the abundance of skin commensals and increased the intensity of Flavobacteriaceae in rainbow trout skin. Similarly, an in vivo study showed that Atlantic salmon infected with sea lice, the ectoparasitic copepod Lepeophtheirus salmonis, were susceptible to skin colonization by known pathogenic bacteria genera, belonging in particular to the Flavobacteriaceae family [52]. Among these bacterial genera was Tenacibaculum sp., a genus that we found correlated with the parasitic load in the gills of D. annularis. Unfortunately, we could not identify the nature of all the bacteria belonging to the Flavobacteriaceae family from our dataset as most remain unidentified at the species or even the genus level. As a result, it remains difficult to speculate on the pathogenicity of these bacteria associated with fish with high parasitic loads. However, numerous studies have shown that fish infected with ectoparasites [59, 60] and especially with monogeneans are more susceptible to numerous pathogenic bacteria [61, 62]. It is therefore likely that the increase in Flavobacteriaceae abundance with the parasitic load observed in our samples involves potentially pathogenic bacteria belonging in particular to this family. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the increased susceptibility of parasitized fish to bacterial infections. Firstly, the artificial abrasion created by the attachment and feeding mode of parasite can induce histopathological changes in host tissues, which are likely to create a gateway for secondary infections [22, 53, 63, 64]. Thus, skin and gill injuries caused by monogeneans would increase the adhesion of pathogenic bacteria. It is also possible that primary infection by a pathogen induces immune stress in the host, reducing its resistance to opportunistic bacterial infections [65]. This could also be the result of the modulation of the immune system by the parasite. Several studies have shown that a variety of strategies can be implemented to circumvent and/or reduce the host immune response, leading to reduced resistance to secondary bacterial infections [66,67,68,69,70]. It has been shown for the monogenean Eudiplozoon nipponicum’s excretory-secretory products (cysteine peptidase inhibitors) lead to a down-regulation of two cytokines produced by macrophages which may prevent inflammation at the invasion site and increased susceptibility to concomitant bacterial infections [71]. Another example of immunomodulation was identified during an infestation of the gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) by the monogenean Sparicotyle chrysophrii. The parasite was found to inhibit the humoral immune system, slowing down the assembly process of its host’s complement complex [72] and a splenic down-regulation of genes implicated in inflammation or apoptosis [73], which may result in a delayed response to secondary infections. Finally, an experimental study showed that a primary infection of Carassius auratus by Dactylogyrus intermedius induced the down-regulation of two immune-related factors (TGF beta and C3). The same study also found that parasitized fish exhibited significantly higher loads of Flavobacterium columnare, suggesting that parasitic infection can enhance bacterial invasion [64]. Taken together, these studies suggest that the effects of Lamellodiscus monogeneans on the epithelium and host immunity can be responsible for the observed changes in bacterial communities and the increase in potentially pathogenic bacterial taxa. However, other bacterial families and genera that were positively correlated with the parasite load in Lamellodiscus monogeneans could not be attributed to any known pathogen and their association with parasitism remains difficult to determine. One hypothesis is that these bacteria could attract parasites in particular through their metabolites. For example, an in vitro experiment with Strongyloides nematodes showed that several isolated bacteria act as key chemosensory cues to guide parasite movement but further studies are needed to characterize the metabolites involved [74].

The origin of the bacteria linked to parasitic infection remains unclear; they could be opportunistic bacteria naturally present in the marine environment or belong to the parasite’s microbiota. Parasite could act as a vector for bacteria, carrying them directly to the host. A recent study showed that the microbiota of infected Leuciscus burdigalensis fins was highly similar to that of the adult and larval crustacean ectoparasite Tracheliastes polycolpus [18]. The authors suggested that the bacteria shared between the infected fin and the crustacean ectoparasite result from a co-infection dynamic between the parasite and its associated microbiota. It has also been shown that the parasite Ichthyophthirius multifiliis can transmit the bacterial pathogen Edwardsiella ictaluri to channel catfish [75]. To our knowledge, microbiota associated with monogeneans is not yet known, although the presence of bacteria on their surfaces has long been observed [76]. Several studies on ectoparasitic copepods have reported the presence of Flavobacteriaceae in their microbiota. For example, a study in 2020 showed that the microbiota of the Atlantic salmon ectoparasite Lepeophtheirus salmonis was dominated by the order Flavobacteriales [77]. Similar results were found in the microbiota of the copepod Caligus rogercresseyi, which is also known to parasitise the Atlantic Salmon [78]. Interestingly, these authors identified several taxa with the ability to secrete bioactive compounds, such as the genus Pseudoaltermonas, on the copepod microbiota. In the present study, we found that this bacterial genus was positively correlated with parasite load in the skin and gills of D. annularis. These microorganisms are known to secrete bioactive compounds with antialgae and antimicrobial properties [79]. A possible role of this bacterial genus could be to increase their resistance and persistence in the fish host. However, it is difficult to determine their exact role in the infestation process as all the bacterial species present in our samples could not be identified. Whether the change in microbiota between parasitized and non-parasitized hosts is due to opportunistic bacteria in the environment or to the contribution of the parasite’s microbiota, it is crucial to understand the dynamics of co-infection between bacterial pathogens and monogeneans. Indeed, these co-infections are often associated with greater damage than that resulting from the isolated presence of just one of either pathogen alone [61, 64, 80, 81].

Interestingly, we found that Vibrionaceae were significantly enriched and negatively correlated to the parasitic load in gills of LP D. annularis fish and the same results were obtained with Fusobacteria in gills of LP P. acarne. Similar result was already reported in 2020, who found higher abundance of Fusobacteria and Vibrionaceae in gill mucus of unparasitized butterflyfish Chaetodon lunalatus compared to other Chaetodon species parasitized by Haliotrema monogeneans [28]. The authors proposed that Fusobacteria increase the mucus production in fish, possibly leading to a thicker layer of mucus on their gills. This thickening could lead to lower oxygen levels, potentially promoting higher hemoglobin levels. Furthermore, a positive correlation was identified between Fusobacteria and three hemoglobin-derived peptides, which may act as antimicrobial and antiparasitic agents and could be produced by extracellular protease microbes that specifically cleave hemoglobin. Similarly, it has been shown that the bogue (Boops boops), a sparid species never parasitized by Lamellodiscus monogeneans, had a higher abundance of Fusobacteria and Vibrionaceae in their gill mucus microbiota than parasitized sparids [35]. Similarly, a study of three tropical fish species - Epinephelus fuscoguttatus, Epinephelus sexfasciatus and Atule mate - have reported negative correlations between intestinal endoparasites (such as digeneans, nematode or cestodes) and the abundance of Vibrio and Photobacterium [82]. We also found a strong negative correlation between the Photobacterium genus and the parasitic load in D. annularis gill microbiota. Interestingly, particularly high relative abundances of Photobacterium spp. were found in the only four individuals without Lamellodiscus in their gills.

To date, Vibrionaceae have primarily been investigated due to their pathogenic potential to humans and aquatic animals but some members of this family are known to display antibacterial effects via secondary metabolites [83, 84]. Little is known on their effect on eukaryotic organisms such as monogeneans. In a 2014 study, a lethal effect of two Vibrionaceae species, Photobacterium halotolerans and Vibrio coralliilyticus, have been observed on two eukaryotic species (Artemia sp. and Caernorhabitis elegans) [85]. However, the secondary metabolites or specific mechanisms involved in this toxicity could not be determined. Finally, Vibrionaceae have already been described as being able to inhibit the settlement and attachment of cyprids in macroalgae, but the mechanisms involved have not yet been deciphered [86]. These studies suggest that members of the Vibrionaceae family are capable of secreting potentially host-protective bioactive compounds. Future studies are needed to test the effect of these bioactive compounds on the host specificity of monogeneans.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings highlight the dynamic nature of fish microbiota in response to parasitic infestations, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive understanding of co-infections dynamics. The observed correlations between specific bacterial families or genera and parasitic load highlight the complex interplay between host, parasite and bacterial communities. Future investigations should explore the specific mechanisms underlying these interactions and the potential applications of bacteria in mitigating parasitic infections in fish.

Data availability

Sequence data will be available upon publication in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) database under the BioProject PRJNA1050994 (https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1050994?reviewer=1au0f72tav24kfm8qkk40jktbq).

Abbreviations

- ASV:

-

Amplicon Sequence Variant

- LP:

-

Lightly Parasitized

- HP:

-

Heavily Parasitized

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis Of Variance

- KW:

-

Kruskal-Wallis

- CI:

-

Conover-Iman

- PCoA:

-

Principal Coordinates Analysis

- LEfSe:

-

Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size

- LDA:

-

Linear Discriminant Analysis

- PERMANOVA:

-

Permutational Multivariate Analysis Of Variance

- BC:

-

Bray-Curtis Dissimilarity Index

- WU:

-

Weighted Unifrac Distance

References

Combes C. The art of being a parasite. University of Chicago Press; 2005.

Hahn MA, Dheilly NM. Experimental models to study the role of microbes in host-parasite interactions. Front Microbiol. 2016;7.

Speer KA. Microbiomes mediate host-parasite interactions. Mol Ecol. 2022;31:1925–7.

Stevens EJ, Bates KA, King KC. Host microbiota can facilitate pathogen infection. PLOS Pathog. 2021;17:e1009514.

Federici E, Rossi R, Fidati L, Paracucchi R, Scargetta S, Montalbani E, et al. Characterization of the skin microbiota in Italian Stream frogs (Rana italica) infected and uninfected by a cutaneous parasitic disease. Microbes Environ. 2015;30:262–9.

Afrin T, Murase K, Kounosu A, Hunt VL, Bligh M, Maeda Y, et al. Sequential changes in the host gut microbiota during infection with the intestinal parasitic nematode Strongyloides Venezuelensis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2019;9:217.

Kashinskaya EN, Simonov EP, Andree KB, Vlasenko PG, Polenogova OV, Kiriukhin BA, et al. Microbial community structure in a host–parasite system: the case of prussian carp and its parasitic crustaceans. J Appl Microbiol. 2021;131:1722–41.

Lutz HL, Gilbert JA, Dick CW. Associations between Afrotropical bats, eukaryotic parasites, and microbial symbionts. Mol Ecol. 2022;31:1939–50.

Rajarajan A, Wolinska J, Walser J-C, Mäder M, Spaak P. Infection by a eukaryotic gut parasite in wild Daphnia sp. associates with a distinct bacterial community. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2022;98:fiac097.

Koch H, Schmid-Hempel P. Socially transmitted gut microbiota protect bumble bees against an intestinal parasite. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:19288–92.

Mockler BK, Kwong WK, Moran NA, Koch H. Microbiome structure influences infection by the Parasite Crithidia bombi in Bumble bees. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2018;84:e02335–17.

Hayes KS, Bancroft AJ, Goldrick M, Portsmouth C, Roberts IS, Grencis RK. Exploitation of the intestinal microflora by the parasitic nematode Trichuris Muris. Science. 2010;328:1391–4.

Verhulst NO, Takken W, Dicke M, Schraa G, Smallegange RC. Chemical ecology of interactions between human skin microbiota and mosquitoes: human skin microbiota and mosquito interactions. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2010;74:1–9.

Mayer M, Schlippe Justicia L, Shine R, Brown GP. Host defense or parasite cue: skin secretions mediate interactions between amphibians and their parasites. Ecol Lett. 2021;24:1955–65.

Reynolds LA, Finlay BB, Maizels RM. Cohabitation in the intestine: interactions among Helminth parasites, bacterial microbiota, and host immunity. J Immunol. 2015;195:4059–66.

Reynolds LA, Finlay BB. Worming their way into the picture: microbiota help Helminths modulate host immunity. Immunity. 2015;43:840–2.

Zaiss MM, Rapin A, Lebon L, Dubey LK, Mosconi I, Sarter K, et al. The intestinal microbiota contributes to the ability of Helminths to modulate allergic inflammation. Immunity. 2015;43:998–1010.

Mathieu-Bégné E, Blanchet S, Rey O, Toulza E, Veyssière C, Manzi S, et al. A longitudinal survey in the wild reveals major shifts in fish host microbiota after parasite infection. Mol Ecol. 2023;32:3014–24.

Shinn A, Pratoomyot J, Bron J, Paladini G, Brooker E, Brooker A. Economic impacts of aquatic parasites on global finfish production. Glob Aquac Advocate. 2015;:58–61.

Doan HV, Soltani E, Ingelbrecht J, Soltani M. Medicinal herbs and plants: potential treatment of Monogenean infections in Fish. Rev Fish Sci Aquac. 2020;28:260–82.

Kearn GC. Experiments on host-finding and host-specificity in the monogenean skin parasite Entobdella soleae. Parasitology. 1967;57:585–605.

Buchmann K. Interactions between monogenean parasites and their fish hosts. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:309–19.

Yoshinaga T. Attachment-inducing capacities of fish skin epithelial extracts on oncomiracidia of Benedenia seriolae (Monogenea: Capsalidae). Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:381–4.

Ohhashi Y, Yoshinaga T, Ogawa K. Involvement of host recognition by oncomiracidia and post-larval survivability in the host specificity of Heterobothrium Okamotoi (Monogenea: Diclidophoridae). Int J Parasitol. 2007;37:53–60.

Igarashi K, Matsunaga R, Hirakawa S, Hosoya S, Suetake H, Kikuchi K, et al. Mucosal IgM antibody with D -Mannose Affinity in Fugu Takifugu Rubripes is utilized by a Monogenean Parasite Heterobothrium okamotoi for Host Recognition. J Immunol. 2017;198:4107–14.

Buchmann K. Lectins in fish skin: do they play a role in host–monogenean interactions? J Helminthol. 2001;75:227–31.

Ohashi H, Umeda N, Hirazawa N, Ozaki Y, Miura C, Miura T. Purification and identification of a glycoprotein that induces the attachment of oncomiracidia of Neobenedenia girellae (Monogenea, Capsalidae). Int J Parasitol. 2007;37:1483–90.

Reverter M, Sasal P, Suzuki MT, Raviglione D, Inguimbert N, Pare A, et al. Insights into the natural defenses of a Coral Reef Fish against Gill Ectoparasites: Integrated Metabolome and Microbiome Approach. Metabolites. 2020;10:227.

Lowrey L, Woodhams DC, Tacchi L, Salinas I. Topographical mapping of the Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Microbiome reveals a diverse Bacterial Community with Antifungal properties in the skin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:6915–25.

Sepahi A, Cordero H, Goldfine H, Esteban MÁ, Salinas I. Symbiont-derived sphingolipids modulate mucosal homeostasis and B cells in teleost fish. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39054.

Kelly C, Salinas I. Under pressure: interactions between commensal microbiota and the Teleost immune system. Front Immunol. 2017;8:559.

Archie EA, Theis KR. Animal behaviour meets microbial ecology. Anim Behav. 2011;82:425–36.

Larsen A, Tao Z, Bullard SA, Arias CR. Diversity of the skin microbiota of fishes: evidence for host species specificity. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2013;85:483–94.

Ruiz-Rodríguez M, Scheifler M, Sanchez-Brosseau S, Magnanou E, West N, Suzuki M, et al. Host species and body site explain the variation in the microbiota associated to wild sympatric Mediterranean Teleost fishes. Microb Ecol. 2020;80:212–22.

Scheifler M, Sanchez-Brosseau S, Magnanou E, Desdevises Y. Diversity and structure of sparids external microbiota (Teleostei) and its link with monogenean ectoparasites. Anim Microbiome. 2022;4:27.

Scheifler M, Magnanou E, Sanchez-Brosseau S, Desdevises Y. Host specificity of monogenean ectoparasites on fish skin and gills assessed by a metabarcoding approach. Int J Parasitol. 2022;52:559–67.

Klindworth A, Pruesse E, Schweer T, Peplies J, Quast C, Horn M, et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e1–1.

Sinclair L, Osman OA, Bertilsson S, Eiler A. Microbial Community Composition and Diversity via 16S rRNA gene amplicons: evaluating the Illumina platform. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0116955.

Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–6.

Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Holmes SP. Exact sequence variants should replace operational taxonomic units in marker-gene data analysis. ISME J. 2017;11:2639–43.

Hall M, Beiko RG. 16S rRNA gene analysis with QIIME2. In: Beiko RG, Hsiao W, Parkinson J, editors. Microbiome Analysis. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2018. pp. 113–29.

Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;41:D590–6.

Yilmaz P, Parfrey LW, Yarza P, Gerken J, Pruesse E, Quast C, et al. The SILVA and all-species living Tree Project (LTP) taxonomic frameworks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D643–8.

Scheifler M, Magnanou E, Sanchez-Brosseau S, Desdevises Y. Host-microbiota-parasite interactions in two wild sparid fish species, Diplodus annularis and Oblada melanura (Teleostei, Sparidae) over a year: a pilot study. BMC Microbiol. 2023;23:340.

McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. Phyloseq: an R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61217.

Heberle H, Meirelles GV, Da Silva FR, Telles GP, Minghim R. InteractiVenn: a web-based tool for the analysis of sets through Venn diagrams. BMC Bioinformatics. 2015;16:169.

Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS, et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R60.

Chiarello M, Villéger S, Bouvier C, Bettarel Y, Bouvier T. High diversity of skin-associated bacterial communities of marine fishes is promoted by their high variability among body parts, individuals and species. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2015;91:fiv061.

Larsen AM, Bullard SA, Womble M, Arias CR. Community structure of skin microbiome of gulf killifish, Fundulus grandis, is driven by seasonality and not exposure to oiled sediments in a Louisiana Salt Marsh. Microb Ecol. 2015;70:534–44.

Schmidt VT, Smith KF, Melvin DW, Amaral-Zettler LA. Community assembly of a euryhaline fish microbiome during salinity acclimation. Mol Ecol. 2015;24:2537–50.

Navarrete P, Magne F, Araneda C, Fuentes P, Barros L, Opazo R, et al. PCR-TTGE analysis of 16S rRNA from Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Gut Microbiota reveals host-specific communities of active Bacteria. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31335.

Llewellyn MS, Leadbeater S, Garcia C, Sylvain F-E, Custodio M, Ang KP, et al. Parasitism perturbs the mucosal microbiome of Atlantic Salmon. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43465.

Zhang X, Ding L, Yu Y, Kong W, Yin Y, Huang Z, et al. The change of Teleost skin commensal microbiota is associated with skin mucosal transcriptomic responses during parasitic infection by Ichthyophthirius multifillis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2972.

Paperna I. Parasites, infections et maladies du poisson en Afrique. Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture; 1982.

Cecchini S, Berni C-V. Influence of temperature on the life cycle of Diplectanum aequans (Monogenea, Diplectanidae), parasitic on sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax (L). J Fish Dis. 1998;21(1):73–5.

Šimková A, Sasal P, Kadlec D, Gelnar M. Water temperature influencing dactylogyrid species communities in roach, Rutilus rutilus, in the Czech Republic. J Helminthol. 2001;75:373–83.

Zhang X-P, Shang B-D, Wang G-T, Li W-X, Yang X, Li Z-Y. The effects of temperature on egg laying, egg hatching and larval development of Dactylogyrus vastator. Acta Hydrobiol Sin. 2015;39:1177–83.

Yang BJ, Zou H, Zhou S, Wu SG, Wang GT, Li WX. Seasonal Dynamics and spatial distribution of the Dactylogyrus species on the gills of Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon Idellus) from a Fish Pond in Wuhan, China. J Parasitol. 2016;102:507–13.

Bandilla M, Valtonen E, Suomalainen L, Aphalo P, Hakalahti T. A link between ectoparasite infection and susceptibility to bacterial disease in rainbow trout. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36:987–91.

Evans JJ, Klesius PH, Pasnik DJ, Shoemaker CA. Influence of natural trichodina sp. parasitism on experimental Streptococcus iniae or Streptococcus agalactiae infection and survival of young channel catfish Ictalurus punctatus (Rafinesque). Aquac Res. 2007;38:664–7.

Shoemaker C, Xu D-H, Klesius PH, Evans J. Concurrent infections (parasitism and bacterial disease) in Tilapia. Proc 8th Int Symp Tilapia Aquac Cairo Egypt. 2008;:1365–75.

Attia MM, Abdelsalam M, Elgendy MY, Sherif AH. Dactylogyrus Extensus and Pseudomonas fluorescens dual infection in farmed common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Microb Pathog. 2022;173:105867.

Rahman T, Suga K, Kanai K, Sugihara Y. Infection kinetics of Tenacibaculum maritimum on the abraded skin of Japanese Flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. Fish Pathol. 2015;50:44–52.

Zhang C, Li D, Chi C, Ling F, Wang G. Dactylogyrus intermedius parasitism enhances Flavobacterium columnare invasion and alters immune-related gene expression in Carassius auratus. Dis Aquat Organ. 2015;116:11–21.

Ilgová J, Salát J, Kašný M. Molecular communication between the monogenea and fish immune system. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2021;112:179–90.

Fast MD, Johnson SC, Eddy TD, Pinto D, Ross NW. Lepeophtheirus salmonis secretory/excretory products and their effects on Atlantic salmon immune gene regulation. Parasite Immunol. 2007;29:179–89.

Cotton S, Donnelly S, Robinson MW, Dalton JP, Thivierge K. Defense peptides secreted by helminth pathogens: antimicrobial and/or immunomodulator molecules? Front Immunol. 2012;3.

Cooper D, Eleftherianos I. Parasitic nematode immunomodulatory strategies: recent advances and perspectives. Pathogens. 2016;5:58.

Hamilton S, McLean K, Monaghan SJ, McNair C, Inglis NF, McDonald H, et al. Characterisation of proteins in excretory/secretory products collected from salmon lice, Lepeophtheirus salmonis. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:294.

Rausch S, Midha A, Kuhring M, Affinass N, Radonic A, Kühl AA, et al. Parasitic nematodes exert Antimicrobial Activity and Benefit from Microbiota-Driven support for host Immune Regulation. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2282.

Ilgová J, Kavanová L, Matiašková K, Salát J, Kašný M. Effect of cysteine peptidase inhibitor of Eudiplozoon Nipponicum (Monogenea) on cytokine expression of macrophages in vitro. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2020;235:111248.

Henry MA, Nikoloudaki C, Tsigenopoulos C, Rigos G. Strong effect of long-term Sparicotyle chrysophrii infection on the cellular and innate immune responses of gilthead sea bream, Sparus aurata. Dev Comp Immunol. 2015;51:185–93.

Piazzon MC, Mladineo I, Naya-Català F, Dirks RP, Jong-Raadsen S, Vrbatović A, et al. Acting locally - affecting globally: RNA sequencing of gilthead sea bream with a mild Sparicotyle chrysophrii infection reveals effects on apoptosis, immune and hypoxia related genes. BMC Genomics. 2019;20:200.

Chavez IN, Brown TM, Assié A, Bryant AS, Samuel BS, Hallem EA. Skin-penetrating nematodes exhibit life-stage-specific interactions with host-associated and environmental bacteria. BMC Biol. 2021;19:221.

Xu D-H, Shoemaker CA, Klesius PH. Ichthyophthirius multifiliis as a potential vector of Edwardsiella ictaluri in channel catfish. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2012;329:160–7.

Cusack R, Cone DK. A report of bacterial microcolonies on the surface of Gyrodactylus (Monogenea). J Fish Dis. 1985;8:125–7.

Dalvin S, Skaftnesmo KO, Malde K, Glover KA, Leong JS, Koop BF, et al. Microbial communities associated with the parasitic copepod Lepeophtheirus salmonis. Mar Genomics. 2020;49:100688.

Gonçalves AT, Collipal-Matamal R, Valenzuela-Muñoz V, Nuñez-Acuña G, Valenzuela-Miranda D, Gallardo-Escárate C. Nanopore sequencing of microbial communities reveals the potential role of sea lice as a reservoir for fish pathogens. Sci Rep. 2020;10:2895.

Holmström C, Kjelleberg S. Marine Pseudoalteromonas species are associated with higher organisms and produce biologically active extracellular agents. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1999;30:285–93.

Xu D, Shoemaker CA, Klesius PH. Evaluation of the link between gyrodactylosis and streptococcosis of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (L). J Fish Dis. 2007;30:233–8.

Assane IM, Prada-Mejia KD, Gallani SU, Weiser NF, Valladão GMR, Pilarski F. Enterogyrus spp. (Monogenea: Ancyrocephalinae) and Aeromonas jandaei co‐infection associated with high mortality following transport stress in cultured Nile tilapia. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2022;69.

Hennersdorf P, Kleinertz S, Theisen S, Abdul-Aziz MA, Mrotzek G, Palm HW, et al. Microbial Diversity and parasitic load in tropical fish of different environmental conditions. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0151594.

Castro D, Pujalte MJ, Lopez-Cortes L, Garay E, Borrego JJ. Vibrios isolated from the cultured manila clam (Ruditapes Philippinarum): numerical taxonomy and antibacterial activities. J Appl Microbiol. 2002;93:438–47.

Wietz M, Mansson M, Gotfredsen CH, Larsen TO, Gram L. Antibacterial compounds from Marine Vibrionaceae isolated on a global expedition. Mar Drugs. 2010;8:2946–60.

Neu AK, Månsson M, Gram L, Prol-García MJ. Toxicity of bioactive and Probiotic Marine Bacteria and their secondary metabolites in Artemia sp. and Caenorhabditis elegans as eukaryotic model organisms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:146–53.

Nasrolahi A, Stratil SB, Jacob KJ, Wahl M. A protective coat of microorganisms on macroalgae: inhibitory effects of bacterial biofilms and epibiotic microbial assemblages on barnacle attachment. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2012;81:583–95.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mathilde Scheifler and the Bio2Mar platform (http://bio2mar.obs-banyuls.fr) for the access to the instrumentation and the advices provided to carry out this project, as well as the “Service des Moyens à la Mer (FR3724) de l’Observatoire Océanologique de Banyuls-sur-Mer” for fish sampling.

Funding

CNRS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YD and EM contributed to the methodology. JR, YD and EM helped in the investigation. JR conducted the formal analysis, data curation, and writing of the original manuscript. YD, EM supervised the study and helped with data interpretation. JR, YD and EM contributed to reviewing and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The Oceanological Observatory of Banyuls-sur-Mer (FR3724) holds the authorization for fishing and housing wild Mediterranean teleosts (Decision n°100/2019, Inter-regional direction of Mediterranean Sea). Wild fish were caught by a competent person and in accordance with the European Union Regulations concerning the protection and welfare of experimental animals (European directive 91/492/CCE).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Revault, J., Desdevises, Y. & Magnanou, É. Link between bacterial communities and contrasted loads in ectoparasitic monogeneans from the external mucus of two wild sparid species (Teleostei). anim microbiome 6, 42 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42523-024-00329-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42523-024-00329-0