Abstract

A 50-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus and a history of aortic arch replacement surgery for Stanford type A aortic dissection experienced a reoccurrence of an ascending aortic aneurysm and coronary artery occlusion. Computed tomography revealed that the aneurysm was compressing the superior vena cava and right atrium. The patient underwent urgent surgery to repair the aneurysm. This case highlights that aortic aneurysms can reoccur even after total arch replacement in systemic lupus erythematosus patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease that predominantly affects women, often leading to vascular complications like aneurysms and dissections [1, 2]. This report focuses on a SLE patient who developed a true aortic aneurysm 17 years after a total arch replacement for acute aortic dissection (AAD).

Case report

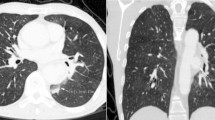

A 50-year-old woman, who has been managing systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) with a daily dose of 4 mg prednisolone since age 18, experienced exertional dyspnea 17 years after undergoing an aortic arch replacement. Computed tomography (CT) showed a 63-mm ascending aortic aneurysm pressing on the superior vena cava and right atrium (Fig. 1). Cardiac catheterization identified a chronic total occlusion in the left anterior descending (LAD) artery. The patient underwent surgery for an ascending aortic aneurysm and occluded coronary artery. Considering the complexities of a reoperation and the long-term use of steroids, we opted for the saphenous vein graft (SVG) for the coronary artery bypass. Additionally, to ensure reliable myocardial protection, the SVG was deemed the most suitable choice for grafting to the LAD.

Computed tomography 3D reconstruction and its schema (a) showing the 63-mm ascending aorta near the proximal anastomosis site. The arrows indicate the aneurysm of the ascending aorta compressing the right atrium. The 2D axial view (b) and the 2D coronal view (c) display the aneurysm located between the previous surgery’s anastomosis site and the sinotubular junction D, dimensional

After median sternotomy and establishment of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), the harvested great saphenous vein was anastomosed to the LAD during systemic cooling to a bladder temperature of 23 °C. Cardioplegia was administered via the coronary ostium and the newly anastomosed saphenous vein graft. Subsequently, the aneurysmal section of the aorta was incised, the distal portion of the artificial blood vessel was clamped, and blood circulation was restored. The ascending aorta was replaced with a 24-mm J-graft (Japan Lifeline Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), with proximal anastomosis performed at the sinotubular junction. The saphenous vein graft was then anastomosed to the J-graft, followed by aortic declamping. The durations of the surgical intervention, cardiac arrest, and circulatory arrest were 494, 113, and 3 min, respectively. No recurrence of the ascending aortic aneurysm was observed over a 2-year follow-up period.

Histology confirmed it as a true aneurysm with pronounced atherosclerotic changes and potential cystic medial necrosis, despite the absence of clear mucopolysaccharide deposits (Figs. 2, 3).

Histological findings of the aneurysm wall with severe atherosclerotic changes. a Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showing that the wall was composed of tunica intima (*), media (**), and externa (***). The tunica intima was thickened by the formation of an atheroma. b Masson–Goldner staining indicating the decrease of smooth muscle (red stained fibers) and the disordered arrangements of elastic fibers (brown to dark stained fibers). Some elastic fibers were ruptured, and fragmented fibers were observed (white arrow)

Higher-magnification image of the aneurysm wall. a Tunica intima showed advanced atheromatous changes with cholesterol clefts. b Masson–Goldner stain showed a cystic crevice between the elastic fibers of the tunica media. c Alcian blue stain did not show definite deposits of acidic mucopolysaccharide in the crevice of the tunica media

Discussion

Aortic dissections and aneurysms, while rare in the context of SLE, demonstrate a higher incidence in these patients compared to age- and sex-matched controls [1, 2]. Notably, SLE predisposes individuals to an earlier manifestation of aortic aneurysms [3]. These vascular anomalies are pathologically linked to cystic medial necrosis, characterized by the accumulation of mucopolysaccharides and Marfan-like alterations, including the deterioration of elastic fibers [4]. The histopathological findings in the present case, particularly the disruption of medial elastic fibers, suggest a potential role of such damage in the initial aortic dissection 17 years prior.

The etiology of aortic aneurysms in SLE extends beyond atherosclerosis to include mucoid degeneration, vascular trauma, hypertension, arteriosclerosis, and the impact of corticosteroid therapy [5]. Long-term corticosteroid administration is known to disrupt chondroitin sulfate synthesis and granulation tissue formation, thus compromising connective tissue integrity and heightening the risk of atherosclerosis [5]. Kurata et al. identified vasculitis and cystic medial degeneration as key factors in aortic aneurysm development in SLE patients, while atherosclerotic changes from prolonged corticosteroid use also play a significant role [6]. The present case exhibited a severe atherosclerotic TAA, with early onset and pronounced atherosclerotic lesions potentially attributable to SLE and sustained corticosteroid treatment. Although no direct evidence linked the initial aortic dissection to cystic medial necrosis, the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection reveals that individuals below 40 with aortic dissection often have underlying connective tissue disorders, suggesting a potential link in this case [7].

The comprehensive study on SLE-related aortic disease by Yuan and colleagues highlighted that aortic aneurysms comprised 67.5% of cases, dissections 27.5%, and concurrent aneurysms and dissections 5% [8]. The prevalence of such complications post-aortic surgery in SLE patients remains unclear due to SLE’s rarity. This case underscores the uniqueness of true aneurysm development in the residual proximal aortic wall long after aortic dissection surgery in an SLE patient. As evidenced by CT imaging, a significant issue in this instance was that too much of the ascending aorta was left intact during the initial operation. Had the entire ascending aorta wall been completely resected at that time, it is conceivable that the need for this reoperation might have been avoided. It is imperative for clinicians to recognize the potential for true aneurysm development in SLE patients even after arch replacement. Surgeons must be vigilant for the emergence of true aneurysms in SLE patients post-arch replacement and ensure no aortic wall segments are left at the aortic root. Given the absence of this specific pathology and its treatment strategy in current guidelines, diligent monitoring and the gathering of additional case reports are crucial for a deeper understanding of aortic dissections and aneurysms in the SLE population.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be made available on reasonable request.

References

Wang SH, Chang YS, Liu CJ, Lai CC, Chen TJ, Chen WS. Incidence and risk analysis of aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. Lupus. 2014;23:665–71.

Guy A, Tiosano S, Comaneshter D, Tekes-Manova D, Shovman O, Cohen AD, et al. Aortic aneurysm association with SLE - a case-control study. Lupus. 2016;25:959–63.

Ohara N, Miyata T, Kurata A, Oshiro H, Sato O, Shigematsu H. Ten years’ experience of aortic aneurysm associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2000;19:288–93.

Choi KH, Rim SJ, Lee SK, Jang BC, Cho SH. Dissecting aortic aneurysm with aortic-valve insufficiency in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:969–73.

Sato J, Kawakami T, Nakabayashi K, Fukuoka K, Hirano K, Terado Y, et al. Multiple aortic aneurysms complicated by a rupture in the systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report. Pathol Res Pract. 2008;204:845–50.

Kurata A, Kawakami T, Sato J, Sakamoto A, Muramatsu T, Nakabayashi K. Aortic aneurysms in systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis of 35 cases in the literature and two different pathogeneses. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2011;20:e1-7.

Evangelista A, Isselbacher EM, Bossone E, Gleason TG, Eusanio MD, Sechtem U, et al. Insights from the international registry of acute aortic dissection: a 20-year experience of collaborative clinical research. Circulation. 2018;137:1846–60.

Yuan SM. Aortic aneurysm and dissection in systemic lupus erythematosus. Z Rheumatol. 2019;78:287–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00393-018-0555-x.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept/design: HS, RK, and MM; drafting the article: HS; critical revision of the article: RK; approval of the article: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Patient consent is obtained.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

During the preparation of this work the author(s) used [Chat-GPT4] in order to [improve grammar and syntax errors and sentence formulation pointed out by the reviewer]. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sasaki, H., Kowatari, R., Imamura, Y. et al. Ascending aortic aneurysm after acute aortic dissection in a case with systemic lupus erythematosus. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Cases 3, 40 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s44215-024-00165-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s44215-024-00165-3