Abstract

Despite broad consensus that most juvenile crimes are committed with peers, many questions regarding developmental and individual differences in criminal style (i.e., co-offending vs. solo offending) remain unanswered. Using prospective 3-year longitudinal data from 937 14- to 17-year-old serious male offenders, the present study investigates whether youths tend to offend alone, in groups, or a combination of the two; whether these patterns change with age; and whether youths who engage in a particular style share distinguishing characteristics. Trajectory analyses examining criminal styles over age revealed that, while most youth evinced both types of offending, two distinct groups emerged: an increasingly solo offender trajectory (83%); and a mixed style offender trajectory (17%). Alternate analyses revealed (5.5%) exclusively solo offenders (i.e., only committed solo offenses over 3 years). There were no significant differences between groups in individuals’ reported number of friends, quality of friendships, or extraversion. However, the increasingly solo and exclusively solo offenders reported more psychosocial maturity, lower rates of anxiety, fewer psychopathic traits, less gang involvement and less self reported offending than mixed style offenders. Findings suggest that increasingly and exclusively solo offenders are not loners, as they are sometimes portrayed, and that exclusively solo offending during adolescence, while rare and previously misunderstood, may not be a risk factor in and of itself.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

One of the most consistent findings in the literature on the social circumstances of juvenile versus adult offending is that adolescents are significantly more likely than adults to commit crimes in groups (Zimring 1981). However, while most adolescents’ crimes are committed in groups, a small proportion of crimes are perpetrated by adolescents acting alone (Reiss 1986; Reiss and Farrington 1991; Shaw and McKay 1969). Importantly, noting that some adolescents’ crimes are committed by individuals acting alone and others by multiple individuals acting together is not the same thing as asking whether some adolescents are characteristically solo offenders and others are characteristically group offenders. It is this latter question that is the focus of this investigation.

The goal of the present study is to determine whether particular juveniles have characteristic styles of offending or a specific “criminal style.” We define criminal style as a function of whether youth consistently commit crimes alone or whether they usually commit crimes with their peers and then examine how these styles change developmentally. In addition, we examine whether adolescents who tend to offend alone are distinguished from their co-offending peers on the basis of their criminal histories, personalities, and social characteristics. Whether criminal styles exist during adolescence and the transition young adulthood, and whether these styles are associated with distinctive characteristics remains unknown—as little research exists on the nature, structure, and process of criminal style. Moreover, our knowledge base regarding patterns of persistence/desistance among serious offenders who are making the transition from adolescence to young adulthood is limited. Within the Criminology literature, there are only a handful (i.e., less than five) studies that examine co-offending issues longitudinally—and most have been with normative/community samples that evince little co-offending and almost no serious offending/offenders.

Despite this gap in the literature, several state legislatures have passed laws differentiating between adolescent crimes committed in groups and those committed alone. Lawmakers may presume that youth who commit crimes in groups are inherently more dangerous, as they may be members of gangs. However, youth who commit crimes alone may actually be more dangerous, as group offending is more developmentally normative. Given this tension, research is needed to better understand whether the social context of an adolescent crime reveals characteristics of the offender that should affect dispositions. Furthermore, by addressing these voids, the present study provides a response to the call put forth by several researchers (McCord and Conway 2002; McGloin et al. 2008) by illuminating the role of group affiliation in crime and delinquency and improving our understanding of the causes, correlates and developmental course of offending. Specifically, the following sections will discuss developmental differences in criminal style, individual differences between solo- and co-offenders, and will conclude with a description of the present study.

Developmental Differences in Criminal Style

Co-offending has long been proposed as the predominant form of delinquent behavior during adolescence (Shaw and McKay 1942). Given the increasing importance of peers during the adolescent years, (Dishion et al. 1996; Labile et al. 2000; Sullivan 1953; Warr 2002) it is not surprising that most youth commit crimes in groups (Erickson 1971; McCord and Conway 2005; Reiss 1986; Reiss and Farrington 1991; Shaw and McKay 1942, 1969; Zimring 1981; Warr 1996). In fact, research suggests that co-offending is particularly common during adolescence whereas solo offending is relatively rare (Decker et al. 1993; Meloy et al. 2001). As youth exit adolescence and enter adulthood, however, group offending declines and solo offending increases (Piquero et al. 2007).

Although most adolescents who violate the law do so with their peers, not all juvenile offenders follow this pattern. Three types of offending styles have been observed: (1) solo offending, engaging in crimes only by oneself; (2) co-offending, always offending with others; and (3) mixed solo and co-offending, engaging in a mixture of both solo and co-offenses (Piquero et al. 2007; Reiss and Farrington 1991). However, while researchers have theorized that three specific categories of criminal style exist, research suggests that exclusively solo offending and/or exclusively co-offending is a rare phenomenon during the adolescent years. For example, Piquero et al. (2007) were able to identify only one exclusively solo offender using data from the Cambridge Study in Delinquency Development (CSDD), a longitudinal study of 411 South London males followed from ages 10–40, and other researchers have been unable to identify any adolescents who always offend alone (Emler et al. 1987). In fact, several studies suggest that youths typically characterized as solo offenders also tend to engage in co-offenses with their peers (Breckinridge and Abbott 1917; Hindelang 1971, 1976; Peoria Crime Reduction Council 1979). Further muddying the waters, is the issue arising from the extent to which self-report versus official arrest data yield different distinctions between co- and solo-offenders. To date, much research on criminal careers generally (Piquero et al. 2003) and co-offending in particular (McCord and Conway 2002; McGloin et al. 2008) has been limited to official records of offending. This is a considerable shortcoming as self-reports may provide a more accurate depiction of offenses committed (e.g., by including some crimes that went unreported/undetected by law enforcement) (Farrington 2003). In an effort to begin to address this important issue, we will examine self-report based criminal style trajectories and compare these groups’ self- and official-report of offending to determine whether criminal style is associated with persistence in offending.

The developmental transition from adolescence to adulthood provides a unique opportunity to examine the trajectory of criminal styles, because this is a transition characterized by a reorganization of peer relationships and a breakdown of the peer “crowd” structure that dominates social relationships in adolescence (Brown 2004) and that presumably contributes to a good deal of adolescent offending (Moffitt 1993). Thus, one may expect co-offending to be prevalent during mid- to late adolescence (and at the peak of the age/crime curve) and to taper off during the 20s, when solo offending should be on the upswing. In fact, a recent analysis of the CSDD data found that the age/co-offending curve mirrored the aggregate age/crime curve (Piquero et al. 2007). Specifically, these authors found that the total number of co-offenders increased between ages 10 and 16, peaked at age 17, and decreased throughout the 20s. This is consistent with Moffitt’s (1993) suggestion that there may be differences between adolescent-limited (AL) offenders and life-course-persistent (LCP) offenders in their criminal styles. According to Moffitt’s model, AL offenders may need to rely on peer support to engage in criminal offenses, whereas LCP offenders may be more willing and able to offend alone. Taken together, this body of findings suggests that during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood, criminal style should be increasingly solo.

This aforementioned developmental pattern of co-offending (i.e., a bell shaped curve peaking at age 17), has been observed in the more general criminological literature as well. For example, Hood and Sparks (1970) found that solo offending did not become the dominant form of offending until the mid-20s. In addition, Reiss and Farrington (1991) and Piquero et al. (2007) described a developmental process in which some individuals began offending with others and then moved into a solo pattern as they aged, a pattern that could not be attributed solely to the attrition of co-offenders from the study. Instead, it seemed to be the case that individuals increased their rate of solo offending as they grew older (although most continued to commit some offenses with others). Among persistent offenders (those who had committed at least 10 offenses by age 40), there was a significant negative correlation between age at conviction and average number of co-offenders (Piquero et al. 2007; Reiss and Farrington 1991). Thus, these researchers suggested that the age-related decline in co-offending reflected behavior changes within an individual’s criminal career.

Individual Differences Between Solo- and Co-Offenders

In addition to the aforementioned developmental differences in criminal style, individual differences are also salient. In particular, one’s psychosocial maturity (responsibility, temperance, and perspective) (Cauffman and Steinberg 2000) may be an important predictor of criminal style. For instance, solo offenders may exhibit more responsibility (e.g., self-reliance, resistance to peer influence) than co-offenders when it comes to the execution of their crimes. In accord with Moffitt’s (1993) suggestion that life course persistent offenders are more willing to offend alone, researchers have implied that solo offenders may not require the aid and reassurance of others in order to offend (Jeglum-Bartusch et al. 1997). While there are no studies, to our knowledge, that tests the association between responsibility and criminal style per se, studies of the relationship between peer influence and co-offending are common. Empirical support for the influence of peers on co-offending dates back to Shaw and McKay’s (1931) report that at least 80% of Chicago juvenile delinquents were arrested in the company of their co-offenders. Thus, it is clear that peer influence impacts co-offenders; yet, whether responsibility relates to solo offenders and the solitary nature of their crimes remains unknown.

The second component of psychosocial maturity, temperance (i.e., impulse control, suppression of aggression), may also be relatively more characteristic of solo offenders. According to Gottfredson and Hirschi’s (1990) General Theory of Crime, co-offending may stem from individuals with poor impulse control being drawn together and then expressing their lack of self-control collectively. In this peer group context, co-offenders may become more reactive and less strategic in their criminal behavior. One study has indicated that co-offenders were more likely to come to the attention of law enforcement or to get caught (Hindelang 1976). More recently, in their discussion of the stability of co-offending, McGloin et al. (2008) speculated that co-offenders lowest in self-control might engage in co-offending more often. These authors imply that the relatively higher frequency of offending among those who tend to co-offend may be due, in part, to their lack of planfulness, but no studies to date have examined whether solo offenders exhibit more temperance than co-offenders.

Considerations of others, coupled with future orientation, makes up the third component of psychosocial maturity, which is referred to as perspective. It is unclear whether solo offenders will exhibit more perspective than co-offenders. Individuals who tend to co-offend may be adept at taking other key players into consideration. On the other hand, weighing the pros and cons of a situation may be more representative of solo offenders. For these youths crimes are not spontaneous social affairs but instead call for careful consideration. (Additionally, individuals who exhibit more temperance should also demonstrate more perspective). That the relationship between perspective and criminal style has not been studied is a considerable oversight as youths’ ability to consider others and look toward the future may be crucial for distinguishing between solo and group offenders.

Although research has not compared solo versus co-offenders with respect to psychosocial maturity, several studies have examined personality characteristics that distinguish these groups. For instance, some have argued that one’s willingness to co-offend may be influenced by the extent to which one trusts others (McCarthy et al. 1998; Weerman 2003). From this perspective, co-offending may be viewed as a social process wherein material and psychological resources are exchanged (Weerman 2003). Conversely, because solo offending does not require social exchange or dependence on others, it may appeal to individuals who are simply less extraverted, or to highly anxious individuals who are mistrustful of others and who may worry about being convicted through the testimony of a co-offender. The combination of anxiety and mistrustfulness may be common, given the observed correlation between negative affectivity and mistrustfulness (Tellegen and Waller 1994).

The relationship between one’s criminal style and psychopathic traits is less clear. Certain characteristics of psychopathy, such as impulsive antisocial deviance, may be more associated with co-offending whereas others, such as emotional and interpersonal detachment, may be more correlated with solo offending. While the association between anxiety, extraversion, psychopathic traits, and criminal style has yet to be simultaneously examined in a sample of juvenile offenders, we would expect that individuals’ anxiety level, personality, and view of others might affect their willingness to co-offend.

Interpersonal factors may also differentiate individuals who co-offend from those who commit crimes alone. The solitary nature of the solo offense has been viewed as a reflection of individuals’ social isolation. Solo offenders have been described in the literature as loners with little or no social contact (Knight and Prentky 1990), free from association with groups or other criminal friends (Allchin 1962) and as scoring lower on measures of sociability, albeit among a sample of sex offenders (Bijleveld and Hendriks 2003).

In fact, an earlier version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed.) taxonomy for conduct disorder contained an undersocialized aggressive conduct disorder (UACD) subtype (DSM-III, American Psychiatric Association 1980; Hewitt and Jenkins 1946; Quay 1993). However, this subclassification no longer exists in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition-Text Revision. Research on UACD youth suggested that they were more likely to have emotion regulation problems (recall that negative affectivity has been linked to solo offending) and to commit antisocial acts alone in contrast to more “socialized delinquents” (Quay 1993, p. 166). Whether or not one has friends is not the same thing as whether one offends alone or with others, however. Thus, while peer-rejected youths often engage in delinquency, the reverse is not always true. Thus, it is important to distinguish between social isolation and solo offending.

Studying the social context of adolescent offending is made more complex when we consider inconsistencies in the literature on the quality of delinquent youths’ friendships. Some researchers have characterized delinquents’ friendships, in comparison to friendships among non-delinquents, as cold, brittle and unstable (Hirschi 1969; Pakiz et al. 1992), and discordant (Claes and Simard 1992; Simons et al. 1991). In contrast, Giordano et al. (1986) described delinquents’ friendships as intimate despite their experiencing more conflicts. It is unclear whether the presence of high quality (i.e., warm, supportive) friendships will vary by one’s criminal style. One might expect that co-offenders by their very nature would be more social (Empey 1982) and may be more likely to report high quality friendships than solo offenders.

Research on delinquents’ peer relationships often raises concerns about gang membership. In fact, the point at which a group of delinquents becomes a gang is still unclear (Miller 1974; Ball and Curry 1995; Short 1997). Groups of co-offenders and gangs have been defined as having unclear and shifting role assignments and definitions, unstable membership (Warr 2002), and transient leadership due to incarceration (Curry and Decker 1998). Because solo offenders may have friends—and quality friends at that—it is natural to ask whether solo offenders can conceivably also be gang members who simply choose to offend alone. We would expect that leaders of gangs, in theory, may execute crimes on their own, but would have to have a degree of interpersonal skill to occupy a leadership position. Those who are not in this leadership position but are instead lower status members may only engage in co-offending.

The Current Study

The current study examines developmental and individual differences in criminal style (i.e., co-offending versus solo offending) during the transition to adulthood. Specifically, we ask (1) Do serious adolescent offenders, in general, engage in more solo offending as they grow older? (2) Are some individuals more likely to engage in more solo offending, as they grow older, than others? and, (3) How do individuals who commit most of their crimes alone compare in terms of psychosocial maturity, personality characteristics, peer associations, and frequency of offending, with those who commit most of their crimes with others?

With regard to our first research question, based on considerable empirical evidence, we expect that adolescent offenders will increasingly engage in solo offenses as they grow older. Our second hypothesis is that there will be heterogeneity in the developmental trajectories of criminal style; some youthful offenders will increasingly engage in solo offenses whereas others will not. Despite the paucity of empirical evidence for individual differences in criminal style, related research suggests that individual differences should also vary between youth with different criminal styles.

As noted earlier, we expect that increasingly solo offenders, compared to their counterparts, will be more psychosocially mature (exhibiting greater responsibility, temperance, and perspective) and yet also more anxious (e.g., distrusting of others, less likely to collaborate in their crimes). In line with this profile, we also expect that increasingly solo offenders would be less extraverted, gang involved, and frequent in their offenses than co- or mixed style offenders. Finally, in accord with previous literature, increasingly solo offenders will report more psychopathic traits and fewer peer associations than co- or mixed style offenders.

In order to test these hypotheses, we have used a more rigorous definition of solo offenders than found in the extant literature. Rather than conflating social isolation with solo offending, as is sometimes done in other studies, our study is among the first to operationalize solo offending in terms of the proportion of offenses that an individual reports committing alone. Another distinctive aspect of the present study is the mapping of developmental trajectories of criminal style using longitudinal data from a sample of serious juvenile offenders, among whom one would expect to find a variety of criminal styles. Moreover, serious adolescent offenders are an ideal sample for studying trajectories of and characteristics associated with criminal style, especially because persistent and serious offending is rare among general population samples of youth (Piquero et al. 2003). The present study also improves upon previous research by investigating whether criminal style is associated with greater self-reported and official-record offending over a 3-year study period. Findings from the current study have the potential to provide new insight into developmental theory of delinquency/criminal trajectories. Specifically, we will be able to determine if a certain criminal style is associated with a greater persistence in offending during adolescence and young adulthood.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study were 937 male adolescents enrolled in the Pathways to Desistance study, a prospective, longitudinal study of serious juvenile offenders in two United States cities (see Mulvey et al. 2004; Schubert et al. 2004); the sample contained too few females to conduct separate analyses, and in light of a large literature on sex differences in social relationships, it did not make sense to combine males and females into a single group.

The adolescents enrolled in the study had all been adjudicated of a serious criminal offense (see below). Participants were interviewed, on average, 36.9 days (SD = 20.6) after their adjudication (for those in the juvenile system) or their decertification hearing in Philadelphia or an adult arraignment in Phoenix (if in the adult system). The mean age at time of adjudication was 15.9 (SD = 1.14), and participants had an average of 1.99 (SD = 2.2) prior petitions. The sample was primarily African American (39%), although there was also a large percentage of Latinos (35%) and Caucasians (21%). Participants were predominantly lower SES, with fewer than 3% of the participants’ parents holding a four-year college degree, and 68% with parents having less than a high-school education.

Adolescents were eligible for the study if they were between 14 and 17 years of age at the time of their offense and adjudicated of a serious crime. Eligible crimes included felony offenses against persons and property, as well as several misdemeanor weapons offenses and sexual assault. The juveniles were sentenced for a range of offenses: 46% for violent crimes against persons (e.g., murder, rape, robbery, assault), 28% for property crimes (e.g., arson, burglary, receiving stolen property), 9% for weapons, 13% for drug crimes, and 4% for other crimes (e.g., conspiracy, intimidation of a witness). As drug law violations represent an especially large proportion of the offenses committed by this age group, the proportion of juvenile males with drug offenses was capped at 15% of the sample at each site to ensure adequate heterogeneity in offense type.

Procedures

The juvenile court in each locale provided the names of eligible adolescents (based on age and adjudicated charge). Interviewers then attempted to contact each eligible juvenile and his or her parent or guardian to ascertain the juvenile’s interest in participation and to obtain parental consent. Once the appropriate consents and assents had been obtained, interviews were conducted either in a facility, if the juvenile was confined, or at the juvenile’s home or a mutually agreed-upon location in the community.

The baseline interview was administered over 2 days in two, 2-h sessions. Interviews and participants sat side-by-side facing a computer, and questions were read aloud to avoid any problems caused by reading difficulties. Respondents could answer the questions aloud or, to maximize privacy, enter their responses on a keypad (although in some facilities, this option was not available). When interviews were conducted in participants’ homes or in community settings, attempts were made to conduct them out of the earshot of other individuals. Honest reporting was encouraged, and confidentiality was ensured by informing participants of the requirement for confidentiality placed upon us by the US Department of Justice, prohibiting our disclosure of any personally identifiable information to anyone outside the research staff, except in cases of suspected child abuse or where an individual was believed to be in imminent danger. All recruitment and assessment procedures were approved by the IRBs of the participating universities. All adolescents were paid for their participation except those who were housed in facilities that would not permit this.

Of 2,008 youths eligible for the study, 1,692 were located and contacted with recruitment information. Parental consent and youth assent were obtained for 80% (N = 1,354) of the youths contacted, 1,171 of whom were males. The retention of our participants has been very high, especially for such a difficult-to-follow sample such as serious, youthful offenders. Specifically, the retention rate at each time point was over 90% with 77% of the participants having complete data (i.e., they had not missed any interviews over the 3-year period). Only 3% of participants dropped out and 3% died over the 3-year period. Participants were included in the present study if they had data on their criminal style for at least two assessments over the 3 years. These exclusion criteria provided for a more rigorous assessment of criminal style as we did not rely on only one assessment point to make this determination. Of the possible 1,171 males, 937 (80%) qualified and constituted our final sample. To ensure that this exclusion of participants did not lead to sample bias, the excluded and study samples were compared on all the variables used in this study, as well their number of previous arrests and age at the first arrest. Out of 12 comparisons, three were statistically significant: the excluded sample was on average 3.6 months older (t[1169] = 4.05, p < .001), had .43 more prior arrests (t[1168] = 2.93, p < .01), and included more black participants (48 vs. 40%, χ2[3] = 9.21, p < .05). Although these comparisons are statistically significant, they are small and do not suggest substantial differences among the two samples.

Measures

Criminal Style

To assess criminal style (solo vs. co-offending), as well as involvement in antisocial and illegal activities, we used an abbreviated version of the widely used and well-validated Self Report of Offending (Huizinga et al. 1991). The SRO consists of 22 yes/no items regarding involvement in different types of crime in the past 6 months, with higher scores indicating participation in more types of delinquent behavior, an index referred to in the criminology literature as a “variety score” (α = .88). Previous research has shown that a variety score provides a consistent and valid estimate of overall involvement in illegal activity over a given recall period (Osgood et al. 2002). A follow up question after each of the 22 items asks about the presence of a co-offender (i.e., “Thinking about the last time [you did X], was anyone with you at that time?”). Individuals who answered “yes” were coded as having committed a co-offense, whereas those who answered “no” were coded as having committed a solo offense. For each assessment time, a total criminal style score was computed to represent exclusively solo offending (coded as 0), mixed offending, i.e., solo offending at some times and co-offending at other times, (coded as 1), and exclusively co-offending (coded as 2).

Psychosocial Maturity

Psychosocial maturity was assessed with a battery of six self-report measures that tap into three components (two measures for each factor) of psychosocial maturity: responsibility, perspective, and temperance (Cauffman and Steinberg 2000).

Responsibility

Responsibility was assessed with the 30-item Psychosocial Maturity Inventory (PSMI, Greenberger and Bond 1976) (α = .89) and the 10-item Resistance to Peer Influence Inventory (RPI, Steinberg and Monahan 2007) (α = .89). The PSMI measures self-reliance (e.g., “In a group I prefer to let other people make the decisions” [reverse coded]), identity (e.g., “I can’t really say what my interests are” [reverse coded]), and work orientation (e.g., “Hard work is never fun” [reverse coded]). The RPI measures adolescent’s propensity to withstand peer influence.

Temperance

Temperance was assessed with the 8-item impulse control (α = .76) and the 7-item suppression of aggression subscales (α = .78) of the Weinberger Adjustment Inventory (Weinberger and Schwartz 1990). Scale items included “I stop and think things through before I act” and “People who get me angry better watch out” (reverse coded), for the impulse control and suppression of aggression scales, respectively.

Perspective

Perspective was assessed with the 7-item consideration of others subscale of the Weinberger Adjustment Inventory (Weinberger and Schwartz 1990) (α = .73) and the 15-item Future Outlook Inventory (Cauffman and Woolard 1999) (α = .68). Scale items included “I try very hard not to hurt other people’s feelings” and “Before making a decision, I weigh the good versus the bad” for the consideration of others and the future outlook inventory, respectively.

Confirmatory factor analysis evaluated structural validity of the psychosocial maturity construct. The model with the three-first-order factors (i.e., temperance, responsibility, and perspective) and the second-order psychosocial maturity factor had the best fit: χ2(6) = 26.47, p < .001; CFI = .978, RMSEA = .055 (.035, .077). Thus, for each of the three measures (i.e., responsibility, perspective taking, and temperance), their two respective subscales were standardized (to overcome the problem with different response categories across different scales) and combined into an average score.

Personality Characteristics

To assess general personality characteristics, three different measures were used.

Trait Anxiety

Trait anxiety was assessed using the 37-item Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (Reynolds and Richmond 1985, 2000). This self-report instrument assesses both the level and the nature of anxiety by asking the participant to respond “yes” or “no” to a series of statements (e.g., “I get nervous when things do not go the right way for me”), with higher scores indicative of more anxious feelings (Reynolds and Richmond 2000).

Extraversion

The extraversion subscale from Costa and McCrae’s (1988) NEO Personality Inventory (α = .72) was used to measure extraversion. Responses for the 12-item extraversion subscale (e.g., “I am known as warm and friendly”) are on a 5-point scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicative of more extraversion.

Psychopathy

The Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version (PCL-YV) was used (Forth et al. 2003) to assess youths’ psychopathy. This 20-item rating scale is based on two sources: (1) an interview with the youth and (2) charts and collateral information. The original semi-structured interview guide (Forth et al. 2004) was adapted for use in this study (Skeem and Cauffman 2001) and reviewed with the interview’s developer. This interview was designed to assess the youth’s interpersonal style and attitudes, obtain information on various aspects of his functioning (psychological, educational, occupational, family, and peer domains), and assess (through comparison with records or collateral reports) the credibility of his statements. Following the interview and a review of records/collateral information, the interviewer used a 3-point ordinal scale to indicate how well each of the 20 items applied to the youth. Higher scores are indicative of a greater number and/or severity of psychopathic characteristics.

Peer Association

Youth’s subjective perceptions of their peer relationships were assessed in three ways: participants provided self-report data regarding their perceived number of friends, quality of their friendships and their level of gang involvement.

Number of Close Friends

To determine the number of close friends, participants were asked “How many close friends do you have?”

Friendship Quality

The Friendship Quality Scale (α = .74), adapted from Pierce’s (1994) Quality of Relationships Inventory was used to assess the quality of youths’ friendships. The scale was originally designed to measure interpersonal support provided by a single romantic partner. However, we adapted this measure to focus on a global rating regarding of perceived social support from the youth’s five closest friends. (e.g., “How much can you count on these people for help with a problem?” “How much do you depend on these friends?”). Responses to 10-items of this type were on a 4-point Likert scale and ranged from “not at all” to “very much,” with higher scores indicating a higher quality friendship.

Gang Membership

A series of questions adapted both from Thornberry et al. (1994) and Elliott (1990) (e.g., “Were you ever a member of a gang/posse?”) were used to assess gang membership. If gang involvement was endorsed, additional items explored the youth’s subjective experience of the gang (i.e., the youth’s position in the gang, the importance of the gang to the youth) and the cohesiveness of the gang (i.e., presence of identifying colors, rules of socialization). For this study, we focused on the following item: “What was your position in your gang/posse?” Response choices were as follows: leader; not a leader, but one of the top people; a member; something else (with higher scores indicative of higher positions in one’s gang/posse). Level of gang involvement was assessed at baseline for engagement over the past 6 months.

Results

Criminal Style Trajectories

Frequencies at baseline revealed that 19% of participants reported engaging in solo offending (solo offender), 44% identified that they offended either alone or with a co-offender (mixed offender), and 37% reported offending only with a co-offender (co-offender). To examine developmental change in these criminal styles, and test our hypotheses that, (1) adolescent offenders will increasingly engage in solo offenses, as they grow older and (2) there will be heterogeneity in the developmental trajectories of criminal style, we conducted a general growth mixture model (GGMM) for ordered polytomous outcome variables (Muthén 2004). This modeling technique allows testing for the presence of distinct developmental trajectories (similar to group-based trajectory methods; Nagin 1999) based on categorical data. In addition, GGMM also allows for variance in growth parameters (e.g., intercepts and slopes). Specifically, in our model we examined criminal style (i.e., solo, mixed, or co-offender) over a 6-year age-range (ages 15–21). Thus, for each individual, there were data that represented a portion of the tested age-range. Mplus allows estimation of the model parameters with such cohort-sequential data with full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation. Likewise, missing observations for predictor variables were handled by the FIML (Enders and Bandalos 2001).

As a starting point, a latent growth curve model for categorical data tested both the linear and quadratic growth over age. There was a significant linear decline over age, blinear = −1.24, p < .01; however, the quadratic term was not significant. Nonetheless, as a subgroup of participants could have potentially followed a pattern of quadratic change, the quadratic term was retained in testing subsequent models. Subsequent GGM models specified random intercepts and slopes whereas the variance of the quadratic growth factors was set to zero. The optimal number of groups and trajectory shapes was guided by the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), the p value for the Lo-Mendel-Rubin likelihood ratio test (LRT; Lo et al. 2001), and the p-value for the Bootstrapped Lo-Mendel-Rubin likelihood ratio test (BLRT; Nylund et al. 2006). A smaller value of BIC indicates a better fit. The LRT and BLRT provide a comparison for a model with k vs. k − 1 classes; thus, significant values of these tests indicate a preference for the k class model and nonsignificant values indicate a preference of the k − 1 class model.

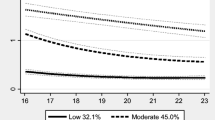

Based on the fit coefficients reported in Table 1, the model with 3 groups had the best fit. However, one of the groups produced by the model included only 4% of participants. This small group size, combined with the relatively small improvement of BIC from the 2- to 3-group model, compelled us to adapt the 2-group model, as the more useful and parsimonious solution (see Nagin 1999; Kreuter and Muthen 2008 for a discussion on substantive reasons for choosing a fewer-group solution). The 2-group model divided the sample into one larger (83% of participants) and one smaller (17% of participants) group. The average posterior probabilities were .90 for Group 1, and .76 for Group 2, indicating moderate to excellent model capabilities in identifying individuals who belong to each group.

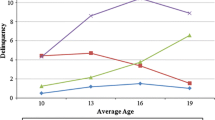

Figure 1a presents the probabilities of engaging in solo offending for the two groups. Because GGMM with categorical data estimates the probability of belonging to a given category (e.g., solo or mixed), the resulting trajectories (Fig. 1a, b) are presented in the probability scale. That is, youths belonging to group 1 had a 30% chance of solo offending at the age of 15, whereas adolescents in group 2 had an 8% chance of solo offending at the same age. For both groups, the probability of solo offending increased over time. Adolescents in group 1 (83%) were more likely to engage in solo offending than the group 2 participants (17%) and increased their relative frequency of solo offending at a faster rate. Thus, we will refer to this group as the “increasingly solo offenders” for the remainder of the paper. Figure 1b presents the probabilities of engaging in a mixed-style offending (i.e., those who offend by themselves at some points and with a co-offender at others). Group 2 participants, whom we will refer to as “mixed style offenders,” were more likely to offend with someone else than the increasingly solo youths.

Similarities and Differences in Individual Characteristics of Increasingly Solo Versus Mixed Style Offenders

Next, we examined the contribution of individual characteristics to group membership in three separate models. Specifically, we tested whether the three markers of psychosocial maturity (i.e., responsibility, temperance and perspective taking), three personality traits (i.e., anxiety, extraversion and psychopathy) and three aspects of social interactions (number of friends, friendship quality, and level of gang involvement) are linked to group membership. These three sets of individual characteristics were tested within the GGM model.

Psychosocial Maturity: Responsibility, Temperance, and Perspective Taking

Of the three measures of psychosocial maturity, temperance and perspective were significantly associated with the trajectories of criminal style. As hypothesized, those who exhibited more temperance (b = 1.16, p < .001) and more perspective (b = .53, p < .01) were more likely to belong to the increasingly solo group. The odds of belonging to the increasingly solo group increased by 3.19 times for each one-point increase in temperance (corresponding to 2.62 times increase in odds for the one standard deviation increase in temperance) and by 1.70 times for each one-point increase in perspective (corresponding to 1.54 times increase in odds for the one standard deviation increase in perspective). Figure 2 illustrates differences among the estimated mean values of temperance and perspective for the two groups. Responsibility, however, was not associated with criminal style (b = .06, n.s.).

Personality Characteristics: Anxiety, Extraversion, and Psychopathic Traits

Of the three personality characteristics tested, anxiety and psychopathic traits were significantly associated with criminal style. Contrary to our hypotheses (that compared to mixed style offenders, increasingly solo offenders would be more anxious yet comparable in their psychopathic-like traits), individuals with higher anxiety and more psychopathic-like traits were more likely to belong to the mixed style offenders group than to the increasingly solo group, b = .06, p < .05 for anxiety and b = .09, p < .001 for psychopathic traits. The odds of belonging to the mixed style offender group increased by 1.06 times for each one-point increase in anxiety (corresponding to 1.39 times increase in odds for the one standard deviation increase in anxiety) and by 1.10 times for each one-point increase in psychopathic traits (corresponding to 2.04 times increase in odds for the one standard deviation increase in psychopathic traits). Differences in estimated means of anxiety and psychopathic traits are presented in Fig. 3. Contrary to our hypothesis that increasingly solo offenders would be less extraverted than their counterparts, extraversion was not significantly linked to criminal style, b = −.31, n.s.

Social Characteristics: Number of Friends, Quality of Friendships and Level of Gang Involvement

Contrary to our hypothesis, the number of friends and the quality of friendship was not significantly linked to criminal style, b = −.02, n.s. for the number of friends and b = −.10, n.s. for the quality of friendships. Level of gang involvement (i.e., leader; not a leader, but one of the top people; a member; something else) was significantly associated with group membership. In accord with our hypothesis, individuals with higher gang involvement were more likely to belong to the mixed style group than to the increasingly solo group, b = .74, p < .001. The odds of being in the mixed style offender group increased by 2.10 times for each one-point increase in gang involvement, aligning with our expected findings. Differences in estimated means of gang involvement are presented in Fig. 4.

Self-Report and Official-Record of Offending Over the 3 Years of the Study

Youths who reported more offending over the 3 years of the study were more likely to belong to the mixed style offender group, b = 5.89, p < .001 than the increasingly solo group, as expected. For each one additional offense, the odds of belonging to the increasingly solo group decreased .003 times. Similarly, adolescents who were arrested more times (as based on official record) were more likely to belong to the mixed style offending group, b = .22, p < .001 than the increasingly solo group. For each additional arrest, the odds of belonging to the mixed style offender group increased by 1.25 times. Differences of estimated means of self-report and official-record offending are presented in Fig. 5.

Identifying Exclusively Solo Offenders

Given that the majority of youth (83%) make up the increasingly solo trajectory, there may be heterogeneity within this group that could not be detected in longitudinal trajectory analyses. The increasingly solo group comprises some youth who have co-offended as well as those who have only ever engaged in solo offenses. Thus, by combining these youth into one group it could be the case that we are not really examining exclusively solo offending. Thus, to ensure that the above findings held for exclusively solo offenders, youths who only engaged in solo offenses across all 7 time points were identified and compared to the remainder of the increasingly solo offenders and the mixed style offenders using ANOVAs. Specifically, a categorical variable was created with three mutually exclusive groups: exclusively solo offenders (individuals that never engaged in co-offending), increasingly solo offenders and mixed style offenders.

A small but substantial subgroup (n = 52, or 5.5% of the sample) of exclusively solo offenders, individuals that had no instances of co-offending across all 7 time points, were identified. ANOVAs indicated that the same pattern of findings that emerged for increasingly solo offenders also held for the exclusively solo offenders. Both increasingly solo offenders and exclusively solo offenders differed significantly from mixed style offenders on all three components of psychosocial maturity: responsibility F (2, 925) = 7.17, p = .001, temperance F (2, 930) = 19.34, p < .001, and perspective F (2, 930) = 7.71, p < .001. Specifically, exclusively solo offenders reported greater levels of psychosocial maturity than mixed style offenders, Scheffe test p’s ≤ .001.

Additionally, the three groups differed significantly on anxiety F (2, 933) = 4.58, p = .01, psychopathic traits F (2, 891) = 6.83, p = .001, and level of gang involvement F (2, 930) = 6.80, p = .001. Compared to mixed style offenders, exclusively solo offenders reported less anxiety, Scheffe test p < .05, fewer psychopathic traits, Scheffe test p = .01 and less gang involvement, Scheffe test p = .01.

The three groups differed significantly on self-reported offending, but not on official number of arrests, F (2, 934) = 182.76, p < .001 for self-reported offending and F (2, 934) = .17, n.s. for the official number of arrests. Exclusively solo youths reported significantly fewer offenses than did mixed style offenders, Scheffe test p < .001. Exclusively solo offenders did not significantly differ from the increasingly solo offenders or mixed style offenders on extraversion F (2, 824) = 2.38, n.s., or with respect to number of friends F (2, 933) = .55, n.s. or quality of friendship F (2, 902) = .60, n.s.

Discussion

The primary purpose of the current study was to examine developmental and individual differences in criminal style (i.e., co-offending vs. solo offending) during the transition to adulthood among a sample of serious juvenile offenders. We focused on whether youths in general engage in more solo offending as they grow older, whether some individuals are more likely to show this pattern than others, and, if so, what psychosocial, personality and interpersonal characteristics distinguish these individuals from their counterparts. Additionally, criminal style groups were compared on both self-reported offending and official arrest records in order to assess frequency and persistence of offending. This study reports the first empirical test to undertake these tasks collectively. Therefore, our line of inquiry benefits from the development of a dynamic measure of criminal style during adolescence and young adulthood, thereby improving our limited knowledge base regarding the nature of youthful offending. Additionally, this research may help inform discussions about whether group offending should be punished more harshly than solo offending. Our data suggests that group offending may say more about adolescence, as a period, than about the adolescents who participate in the activity.

Our analyses indicated that a majority of youths followed an increasingly solo offender trajectory (83%) and the remainder followed a mixed style offending trajectory (engaging in both co- and solo-offenses) (17%). The finding that most youth engage in solo offending (as assessed via self-report) as they get older replicates the findings from the Cambridge Study in Delinquency Development that employed official conviction records (Reiss and Farrington 1991; Piquero et al. 2007). Contrary to this pattern of findings, research by Stolzenberg and D’Alessio (2008), based on official-record data from National Incident-Based Reporting System data for 2002, suggest that solo offending represents the bulk of criminal activity across all age groups. This finding however, is the exception in the literature, as most studies find co-offending to be the dominant criminal style in adolescence. Thus, when contrasted to extant literature, our results are not as extreme as Stolzenberg and D’Alessio’s nor do they suggest that co-offending is the dominant criminal style in adolescence. Instead, our results suggest that an increasingly solo offender trajectory is the predominant criminal style during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood.

It is important to note that our data describe a sample of youthful offenders during the peak of their criminal career. While these data do not follow these youth into late adulthood, they do provide an accurate snapshot of their criminal style during adolescence and, more importantly, as they make their transition into adulthood. It is by focusing on this developmental period that we were able to (1) determine that increasingly and exclusively solo offenders do exist during adolescence and (2) debunk media stereotypes of solo offenders as highly dangerous, psychopathic loners.

Furthermore, the findings of the present study are strengthened by the use of multiple statistical approaches to analyzing the data. Based on the trajectory analyses, we learn that moving away from co-offending is a normative pattern for a majority of adolescents, and that those who do so are more mature than mixed style offenders. From the descriptive analyses, we learn that exclusively solo offenders do indeed exist in adolescence. Although previous research holds that engaging in solo offending is a rare phenomenon, especially during the adolescent years (Emler et al. 1987; Piquero et al. 2007), the present study documented a subgroup of adolescents who engaged in exclusively solo offenses (5.5%) over a 3 year period. Had we not employed both statistical approaches, the exclusively solo offenders in our sample would have gone undetected. In addition, the individual characteristics of the larger, increasingly solo offender group were also representative of exclusively solo offenders (e.g., greater psychosocial maturity, less anxiety, fewer psychopathic traits). Thus, we hold that it is important to conduct empirically based trajectory analyses in conjunction with a more theory driven, descriptive approach.

Findings from this study suggest that increasingly and exclusively solo offenders are not misanthropic loners, as they are sometimes portrayed. Whether we look at the trajectory group of the increasingly solo youth or the smaller group of exclusively solo offenders, solo offending is not due to level of extraversion, number of friends, or the quality of one’s friendships. These findings caution against characterizing the solo offender as a social isolate or loner, or using operational definitions of solo offending that are based on this assumption. A more comprehensive definition of solo offenders should distinguish between the social context of their day-to-day life and the social context of their criminal behavior.

Whereas solo offenders exhibited social similarities with those whose pattern was one of mixed offending, the solo offenders differed in some important ways. First, solo offenders demonstrated significant differences in psychosocial maturity from mixed style offenders. Youths in the increasingly solo trajectory group exhibited greater temperance and perspective than youths in the mixed style trajectory group. (Exclusively solo offenders reported greater levels of psychosocial maturity across all three factors [responsibility, temperance, and perspective] as compared to mixed offenders.) Second, solo offenders engaged in fewer offenses than mixed style offenders over the 3-year study period. According to both self-report and official-record of offending, youth in the increasingly solo trajectory group engaged in fewer offenses than youth in the mixed style trajectory group. (Exclusively solo offenders reported less offending than mixed style offenders.) Taken together, these findings suggest that increasingly solo and exclusively solo offenders’ greater self control, consideration of others and future orientation may, in part, explain why they tend to offend less frequently. Thus, it may be the case that, for increasingly solo and exclusively solo offenders, crimes are not spontaneous social affairs but instead require careful planning. Alternately, increasingly and exclusively solo offenders may be more opportunistic, choosing only crimes that have a low probability of detection. Whether or not this relates to solo offenders being more culpable for their actions than mixed style offenders requires further investigation.

That solo offenders compared to mixed style offenders exhibited less anxiety and fewer psychopathic traits are important distinctions. These findings are in contrast with our notion that one’s anxiety level and psychopathic traits may affect one’s willingness to co-offend. In light of these findings, the profile of increasingly solo offenders appears to be more normative than expected. While solo offending in adulthood has been linked to a host of negative correlates (e.g., divorce, drug dependency, mortality) (Blokland et al. 2005), being an increasingly or exclusively solo offender in adolescence may not be as problematic—at least in the short term. That is, most delinquent youth follow an increasingly solo offending trajectory, thus solo offending during adolescence, while rare and previously misunderstood, may not be a risk factor in and of itself. Further support for this notion comes from our exclusively solo profile. That these youth exist and actually look more like the majority of serious adolescent offenders in terms of psychosocial, personality, and interpersonal characteristics is particularly revealing and may provoke modification to the portrait of solo offending painted by Moffitt’s characterization of life course persistent offenders.

The present study has limitations that should be noted. First, as peer reports of friendships were not assessed, we cannot be certain that the friendships that solo offenders believed were intact were indeed reciprocated. Similarly, friendship quality was based solely on youths’ self report. Thus, additional data are needed to assess whether solo offenders tend to overestimate or erroneously characterize the nature of their peer relationships. Specifically, future research should include linked, peer nominations of friendship as well as peer reports of friendship quality. While we were unable to validate whether these friendships were characterized as high quality, using peer report, research suggests that this may not matter—what matters is one’s perception of these friendships (Mayeux and Cillessen 2008). Second, the present findings are limited to males only. Given the paramount importance of interpersonal relationships to females (Moretti and Higgins 1999), future research should focus on understanding criminal style as a means of unraveling patterns of female delinquency. As the present study focuses solely on serious adolescent offenders, additional research should also examine the criminal style patterns of misdemeanor level offenders as well as community samples of delinquent youths. Finally, as our study was limited to a 3-year window during adolescence (ranging from 15 years of age to 21 years of age), it will be important for future research to examine how co- and solo offending patterns change over the life course and whether the factors related to these changes are similarly related at different stages of the life course.

As, McCord and Conway (2002) noted, a better understanding of the role of group affiliation in crime and delinquency is critical to understanding the causes, correlates, and developmental course of offending. McCord and Conway likely had group offenders in mind when they wrote this, but we hold that the same could be said for research on solo offenders. The findings of the present study, indicating the ways in which adolescents who commit crimes alone do, and do not, differ from those who typically engage in both co- and solo-offenses, should inform further research on this phenomenon.

References

Allchin, W. H. (1962). Some positive aspects of delinquent behaviour. British Journal of Criminology, 3, 38–46.

American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Ball, R. A., & Curry, G. D. (1995). The logic of definition in criminology: Purposes and methods for defining ‘gangs’. Criminology, 33, 225–245.

Bijleveld, C., & Hendriks, J. (2003). Juvenile sex offenders: Differences between group and solo offenders. Psychology, Crime, and Law, 9, 237–245.

Blokland, A. A. J., Nagin, D., & Nieuwbeerta, P. (2005). Lifespan offending trajectories of a Dutch conviction cohort. Criminology, 43, 919–954.

Breckinridge, S. P., & Abbott, E. (1917). The delinquent child and the home. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Brown, B. B. (2004). Adolescents’ relationships with peers. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (2nd ed., pp. 363–394). New York: Wiley.

Cauffman, E., & Steinberg, L. (2000). (Im)maturity of judgment in adolescence: Why adolescents may be less culpable than adults. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 18, 741–760.

Cauffman, E., & Woolard, J. (1999). Future outlook inventory. Unpublished test.

Claes, M., & Simard, R. (1992). Friendship characteristics of delinquent adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 3, 287–301.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1988). Personality in adulthood: A six-year longitudinal study of self-report and spouse ratings on the NEO Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 853–863.

Curry, G. D., & Decker, S. H. (1998). Confronting gangs: Crime and community. Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury.

Decker, S., Wright, R., & Logie, R. (1993). Perceptual deterrence among active residential burglars: A research note. Criminology, 31, 135–147.

Dishion, T., Spracklen, K., Andrews, D., & Patterson, G. (1996). Deviancy training in male adolescent friendships. Behavior Therapy, 27, 373–390.

Elliott, D. S. (1990). National youth survey. Institute of Behavioral Science. University of Colorado.

Emler, N., Reicher, S., & Ross, A. (1987). The social context of delinquent conduct. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 28, 99–109.

Empey, L. T. (1982). American delinquency. Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press. (rev. ed).

Enders, C. K., & Bandalos, D. L. (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling, 8, 430–457.

Erickson, M. L. (1971). The group context of delinquent behavior. Social Problems, 19, 114–129.

Farrington, D. P. (2003). What has been learned from self-reports about criminal careers and the causes of offending? Report for the Home Office. London: Home Office.

Forth, A., Kosson, D., & Hare, R. (2003). The hare psychopathy checklist: Youth version, technical manual. New York: Multi-Health Systems Inc.

Forth, A., Kosson, D., & Hare, R. (2004). The hare psychopathy checklist: Youth version (PCL-YV)—rating guide. Toronto, ON: Multi Health Systems.

Giordano, P. C., Cernkovich, S. A., & Pugh, M. D. (1986). Friendship and delinquency. American Journal of Sociology, 91, 1170–1201.

Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Greenberger, E., & Bond, L. (1976). Technical Manual for the psychosocial Maturity Inventory. Program in Social Ecology, University of California, Irvine.

Hewitt, L. E., & Jenkins, R. L. (1946). Fundamental patterns of maladjustment: The dynamics of their origins. Springfield: State of Illinois.

Hindelang, M. J. (1971). Age, sex, and the versatility of delinquent involvements. Social Problems, 18, 522–535.

Hindelang, M. J. (1976). With a little help from their friends: Group participation in reported delinquent behavior. British Journal of Criminology, 16, 109–125.

Hirschi, T. (1969). The causes of delinquency. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Hood, R., & Sparks, R. (1970). Key issues in criminology. London: World University Library.

Huizinga, D., Esbensen, F.-A., & Weihar, A. (1991). Are there multiple paths to delinquency? Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 82, 83–118.

Jeglum-Bartusch, D. R., Lynam, D. R., Moffitt, T. E., & Silva, P. A. (1997). Is age important? Testing general versus developmental theories of antisocial behavior. Criminology, 35, 13–48.

Knight, R. A., & Prentky, R. A. (1990). Classifying sexual offenders: The development and corroboration of taxonomic models. In W. L. Marshall, D. R. Laws, & H. E. Barbaree (Eds.), Handbook of sexual assault: Issues, theories, and treatment of the offender (pp. 23–52). New York: Plenum Press.

Kreuter, F., & Muthen, B. (2008). Analyzing criminal trajectory profiles: Bridging multilevel and group-based approaches using growth mixture modeling. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 24, 1–31.

Labile, D. J., Carlo, G., & Raffaelli, M. (2000). The differential impact of parent and peer attachment on adolescent adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29, 45–59.

Lo, Y., Mendell, N. R., & Rubin, D. B. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88, 767–778.

Mayeux, L., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2008). It’s not just being popular, it’s knowing it, too: The role of self-perceptions of status in the associations between peer status and aggression. Social Development, 17, 871–888.

McCarthy, B., Hagan, J., & Cohen, L. E. (1998). Uncertainty, cooperation, and crime: Understanding the decision to co-offend. Social Forces, 77, 155–176.

McCord, J., & Conway, K. P. (2002). Patterns of juvenile delinquency and co-offending. In E. Waring, D. Weisburd, L. Sherman, & F. Earls (Eds.), Advances in criminological theory (Vol. 10). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

McCord, J., & Conway, K. P. (2005). Co-offending and patterns of juvenile crime. National Institute of Justice Research Brief.

McGloin, J. M., Sullivan, C. J., Piquero, A. R., & Bacon, S. (2008). Investigating the stability of co-offending and co-offenders among a sample of youthful offenders. Criminology, 46, 155–188.

Meloy, J. R., Hempel, A. G., Mohandie, K., Shiva, A., & Gray, B. T. (2001). Offender and offense characteristics of a nonrandom sample of adolescent mass murderers. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 719–728.

Miller, W. B. (1974). American youth gangs: Past and present. In A. Blumberg (Ed.), Current perspectives on criminal behavior. New York, NY: Knopf.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701.

Moretti, M. M., & Higgins, E. T. (1999). Own versus other standpoints in self-regulation: Developmental antecedents and functional consequences. Review of General Psychology, 3, 188–223.

Mulvey, E. P., Steinberg, L., Fagan, J., Cauffman, E., Piquero, A. R., Chassin, L., et al. (2004). Theory and research on desistance from antisocial activity among serious adolescent offenders. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 2, 213–236.

Muthén, B. (2004). Latent variable analysis. Growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In D. Kaplan (Ed.), The Sage handbook of quantitative methodology for the social sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Nagin, D. S. (1999). Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods, 1, 139–157.

Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2006). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study.

Osgood, D. W., McMorris, B. J., & Potenza, M. T. (2002). Analyzing multiple-item measures of crime and deviance I: Item response theory scaling. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 18, 267–296.

Pakiz, B., Reinherz, H., & Frost, A. K. (1992). Antisocial behavior in adolescence: A community study. Journal of Early Adolescence, 12, 300–313.

Peoria Crime Reduction Council. (1979). Criminal activity of juvenile residential burglars, Peoria, IL: City of Peoria.

Pierce, G. R. (1994). The quality of relationships inventory: Assessing the interpersonal context of social support. In B. R. Burleson, T. L. Albrecht, & I. G. Sarason (Eds.), Communication of social support: Message, interactions, relationship and community. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Piquero, A. R., Farrington, D. P., & Blumstein, A. (2003). The criminal career paradigm: Background and recent developments. In M. Tonry (Ed.), Crime and justice: A review of research (Vol. 30). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Piquero, A. R., Farrington, D. P., & Blumstein, A. (2007). Key issues in criminal career research: New analyses of the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Quay, H. C. (1993). The psychobiology of undersocialized aggressive conduct disorder: A theoretical perspective. Development and Psychopathology, 5, 165–180.

Reiss, A. J. (1986). Why are communities important in understanding crime? In A. J. Reiss & M. Tonry (Eds.), Communities and crime. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Reiss, A. J., & Farrington, D. P. (1991). Advancing knowledge about co-offending: Results from a prospective longitudinal survey of London males. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 82, 360–395.

Reynolds, C. R., & Richmond, B. O. (1985). Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale. RCMAS Manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Reynolds, C. R., & Richmond, B. O. (2000). Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale. RCMAS Manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Schubert, C. A., Mulvey, E. P., Steinberg, L., Cauffman, E., Losoya, S. H., Hecker, T., et al. (2004). Operational lessons from the Pathways to Desistance Project. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 2, 237–255.

Shaw, C., & McKay, H. D. (1931). Report on the causes of crime, 11. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Shaw, C., & McKay, H. D. (1942). Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Shaw, C. R., & McKay, H. D. (1969). Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. (rev. ed.).

Short, J. F. (1997). Poverty, ethnicity, and violent crime. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Simons, R. L., Whitbeck, L. B., Conger, R. D., & Conger, K. J. (1991). Parenting factors, social skills, and value commitments as precursors to school failure, involvement with deviant peers and delinquent behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 20, 645–664.

Skeem, J. L., & Cauffman, E. (2001). Psychopathy checklist, youth version: Interview guide. Unpublished interview.

Steinberg, L., & Monahan, K. C. (2007). Age differences in resistance to peer influence. Developmental Psychology, 43, 1531–1543.

Stolzenberg, L., & D’Alessio, S. J. (2008). Co-offending and the age-crime curve. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 45, 65–86.

Sullivan, H. S. (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. New York: Norton.

Tellegen, A., & Waller, N. G. (1994). Exploring personality through test construction: Development of the multidimensional personality question. In S. R. Briggs & J. M. Cheek (Eds.), Personality measures: Development and evaluation. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Thornberry, T. P., Lizotte, A. J., Krohn, M. D., Farnworth, M., & Jang, S. J. (1994). Delinquent peers, beliefs, and delinquent behavior: A longitudinal test of interactional theory. Criminology, 32, 47–83.

Warr, M. (1996). Organization and instigation in delinquent groups. Criminology, 34, 11–37.

Warr, M. (2002). Companions in crime: The social aspects of criminal conduct. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Weerman, F. M. (2003). Co-Offending as social exchange: Explaining characteristics of co-offending. The British Journal of Criminology, 43, 398–416.

Weinberger, D. A., & Schwartz, G. E. (1990). Distress and restraint as superordinate dimensions of self-reported adjustment: A typological perspective. Journal of Personality, 58, 381–417.

Zimring, F. E. (1981). Kids, groups, and crime: Some implications of a well-known secret. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 72, 867–885.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by funds from the following: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, National Institute of Justice, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, William T. Grant Foundation, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, William Penn Foundation, Center for Disease Control, National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA019697), Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency, and the Arizona Governor’s Justice Commission. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of these agencies.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Goldweber, A., Dmitrieva, J., Cauffman, E. et al. The Development of Criminal Style in Adolescence and Young Adulthood: Separating the Lemmings from the Loners. J Youth Adolescence 40, 332–346 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9534-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9534-5