Abstract

The management of people who inject drugs (PWID) is compounded by the presence of psychiatric comorbidities leading to frequent relapses and poor treatment outcomes. Early identification and treatment of psychiatric comorbidities should be included in the management to enhance treatment outcomes. The objective of this study was to estimate the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities and concurrent substance use among opioid injectors. This hospital-based, cross-sectional study was conducted from March 2021 to August 2022. This study included opioid injectors of all ages and both sexes. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview-7 (MINI-7) and WHO-ASSIST were used to determine psychiatric comorbidities and concurrent substance use, respectively. Both crude and adjusted odds ratios were calculated to assess associations among demographic variables, concurrent substance use and psychiatric comorbidities. Among the 328 opioid injectors, the overall prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities was 88.1%, with the majority (68.6%) having more than one comorbidity. The most common psychiatric comorbidities were panic disorder (41.2%), social anxiety disorder (40.5%), and antisocial personality disorder (39.3%). Concurrent use of alcoholic beverages doubled the risk of ASPD (odds ratio 2.14 (1.24–3.72)). Cocaine (odds ratio 2.36 (1.10–5.03)) and amphetamines (odds ratio 7.68 (2.21–26.65)) increased the risk of OCD. Daily heroin injections were negatively associated (odds ratio 0.18 (0.03–0.94)) with psychotic disorders. Younger age (adjusted odds ratio 0.20 (0.79–0.53)) and never married status (adjusted odds ratio 2.62 (1.06–6.47)) were the only significant variables in the regression analysis. In conclusion, opioid injectors had a higher prevalence of numerous psychiatric comorbidities. The most common comorbidity was anxiety disorders. Concurrent use of tobacco, cannabis, cocaine, inhalants, etc., greatly increased the risk of psychiatric comorbidities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Worldwide, 11 million individuals use injection drugs1. Approximately 8.5 million people in India alone inject drugs. Except for the Union Territories of Andaman and Nicobar and Lakshadweep, injection drug use (IDU) has been documented in all states across the nation. In Jammu and Kashmir, there are an estimated 25,000 people who inject drugs (PWID)2. Injection drug use is the most dangerous method of drug abuse. Following an injection, a large bolus of the drug is instantly carried into the bloodstream and rapidly delivered to the brain. As a consequence, PWID are more likely to experience dependence and overdose than people who abuse drugs by other routes. Maladaptive thoughts in PWID with negative affect undermine the desire to care for themselves. This attitude poses a risk for the transmission of blood-borne diseases3. Worldwide, previous research has shown that heroin is the most abused substance (53%), followed by methamphetamine (43%) and cocaine (40%)4. In Asia, heroin is the most commonly injected substance, and approximately 70–80% of PWID have a background of polydrug use5. In India, PWID opt to inject one or more opioid drugs2.

Comorbid psychiatric illnesses complicate the treatment of such patients, adding to the burden experienced by PWID. The term ‘comorbidity’ was introduced in medicine to refer to cases with a distinct clinical course in addition to the index illness. The term ‘dual diagnosis’ (DD) refers to the coexistence of a specific substance use disorder (SUD) and other psychiatric illnesses (non-SUD)6. Psychiatric comorbidities can be independent of either drug use or substance use. These illnesses can contribute to substance use disorders via a combination of biological and environmental pathways7. According to previous studies, opioid users have the highest prevalence of dual diagnoses8. Approximately 40% of PWID have psychiatric comorbidities, and 51% of psychiatric patients have substance use disorders5,9. Polydrug abuse, which is prevalent among PWID, is ascribed to the presence of comorbid psychiatric disorders10. Patients with substance abuse and psychiatric comorbidities are difficult to manage due to a variety of factors. Multiple clinical presentations, the severity of symptoms, a greater number of relapses, a poor prognosis, increased hospitalization length of stay, and higher suicide rates result in lower chances of recovery7,11. The similarities in the presentation of psychiatric comorbidities with substance intoxication and withdrawal effects make proper and timely diagnosis challenging12. According to previous studies, clinicians frequently underdiagnose psychiatric comorbidities among drug users, which has an impact on treatment plans for such patients13. As a result, greater vigilance towards comorbidities is needed when managing patients with substance use disorders for holistic patient management6.

For decades, the Kashmir region has been in turmoil14. Several studies have found an increase in the prevalence of psychiatric illnesses such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression15. Due to political turmoil, the state has experienced extended lockdown periods in recent years, during which residents have been confined to their homes. Conflict, traumatic experiences, economic development constraints, and the breakdown of conventional social support mechanisms have all contributed to psychological distress in this population16,17,18. Young people represent the most susceptible section of society for a variety of reasons, including uncertainty about the future, a lack of employment, an internet ban, overwhelming fear, and a lack of self-esteem14. This has paved the way for a rise in psychiatric disorders and poor coping strategies such as drug abuse among young people. Substance abuse has largely gone undetected19. Various sociocultural and geographical factors play an essential role in the onset, maintenance, and treatment of substance use disorders20. According to recent research on substance use in Jammu and Kashmir, the prevalence of substance use is 1.95%21, with a total number of 25,000 PWID in the entire state2,21. While the relationship between various drugs and psychiatric comorbidities has been studied in various parts of the world, few studies on injection drug abuse and comorbid psychiatric disorders in Kashmir have been conducted5,7,22,23,24.

In the above context, this study was carried out to estimate the prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders among opioid-injecting drug users. Furthermore, this study also assessed the prevalence of concurrent substance use and its association with psychiatric disorders.

Results

Of the 328 opioid injectors enrolled in this study, 324 (98.8%) and 4 (1.2%) were males and females, respectively. The age of the participants ranged from 17 to 42 years, with a mean of 25.31 ± 5.32 years. The majority, 188 (57.3%), of the study participants were in the 15–24 age group. A total of 121 (36.9%) participants had an intermediate level of education, and 74 (22.6%) had a high school certificate. Only 97 (29.6%) of the participants were currently married.

The study participants had initiated opioid injections at a mean age of 21.77 ± 5.65 years. Peer pressure (47.9%) was the most common reason for the initiation of injections, whereas 14.6% and 11.3% reported initiation due to curiosity and pleasure, respectively. Most (64.3%) of the participants were referred for treatment by friends, followed by family (20.7%) and physicians (9.8%). Of the opioid users, only 36.3% reported a family history of substance use. Psychiatric comorbidities were present in 88.1%, of which the majority (68.6%) had more than one psychiatric comorbidity (Table 1).

The most common psychiatric comorbidity was panic disorder (41.2%), followed by social anxiety disorder (40.5%) and antisocial personality disorder (39.3%). Major depressive disorder (17.7%), alcohol use disorder (14.6%), bipolar affective disorder (8.23%), obsessive–compulsive disorder (11%), and psychotic disorders (3%) were the other frequent disorders found in the study. Most of the study participants (70.4%) had low intent for suicidality. Medium and high intent was found in 20.4% and 9.1%, respectively (Table 2).

Codeine, oral tramadol, tapentadol, and the use of multiple drugs over time by opioid injectors showed a significant (P < 0.05) relationship with the development of psychiatric comorbidities. Using a combination of drugs was negatively associated with psychiatric comorbidities in people who inject drugs (Table 3).

Further analysis showed an association of concurrent drug use with some major psychiatric disorders. Alcoholic beverage intake doubled the risk (odds ratio 2.14 (1.24–3.72) of ASPD, while cannabis abuse nearly tripled (odds ratio 2.95 (1.28–6.80) the risk of MDD. Cannabis also increased (odds ratio 1.93 (1.13–3.30)) the risk of ASPD. Cocaine (odds ratio 2.36 (1.10–5.03) and amphetamine (odds ratio 7.68 (2.21–26.65) increased the risk of OCD in opioid injectors. Inhalants increased the risk of ASPD by 2.5 (2.59 (1.55–4.33)) and OCD by 2.4 (odds ratio 2.44 (1.19–5.01)) (Table 4).

The risk of developing anxiety as a psychiatric comorbidity was increased by the use of tobacco (odds ratio 7.33 (1.49–35.95), alcoholic beverages (odds ratio 2.02 (1.21–3.38), cannabis (odds ratio 2.02 (1.21–3.38), cocaine (odds ratio 2.81 (1.40–5.65), inhalants (odds ratio 2.07 (1.15–3.72), sedatives (odds ratio 2.30 (1.43–3.69), and hallucinogens (odds ratio 4.13 (1.70–10.06). Daily heroin intake was negatively associated with psychotic disorders (odds ratio 0.18 (0.03–0.94)) (Table 5).

In the binary logistic regression, younger age and never married status were significantly associated with the development of psychiatric comorbidities. Younger age (adjusted odds ratio 0.20 (0.79–0.53)) was a protective factor, while never married status ((adjusted odds ratio 2.62 (1.06–6.47)) increased the odds of psychiatric comorbidities (Table 6).

Discussion

Comorbid psychiatric illnesses with injection drug use complicate management and put both caregivers and affected individuals in difficult situations. Understanding the issue of psychiatric comorbidities and concurrent substance use among opioid people who inject drugs is important in the context of pharmacotherapy and improved treatment outcomes.

The majority of our participants were male. Most of the participants were in the 15–24 age group, with a mean age of 25 ± 5.32 years. More than half of our participants had never been married, and the majority lived with nuclear family. The sociodemographic profiles of our participants were similar to those of participants in previous studies conducted by Yasir et al.21, Andreecia et al.25, and Trouiller P et al.7. Similar findings were reported by Nizam Ud Din et al. in their study on substance users26. However, in the study conducted by Andreecia et al.25, the majority of the participants were married and older. Our study also included participants < 18 years of age, which could partly explain the lower age distribution and never married status of most participants. Equal representation of subjects from nuclear and joint families was reported by Yasir et al.21, while in our study, 79.9% had nuclear families. This can be explained by the difference in the settings (community vs. hospital-based) in which the studies were conducted.

In this study, all the participants were injecting heroin. Yasir Hassan et al.21 and Trouiller P et al.7 also reported 91.12% and 100% heroin users among PWID, respectively. However, Armstrong et al.27 found buprenorphine to be the major injectable in 77% and heroin in 18% of the participants. This might be related to the availability of heroin in the study area. Nearly all of the participants had used tobacco products in the last three months. Alcoholic beverages, cannabis, and sedatives were used by 74.7%, 74.1%, and 50.9% of participants, respectively. However, these findings differed from those of the study conducted by Andreecia M et al.25, in which the most commonly abused substance (barring tobacco products) with opioids was cannabis followed by alcohol. The results from the study by Yasir et al.21 reported lifetime use of cannabis, alcohol, and sedatives-hypnotics in 50.33%, 21.33%, and 18.33% of participants, respectively. This difference in the prevalence of use of these substances between our study and the study by Yasir et al. could be because the current study was based exclusively on opioid injectors.

The average age of initiation of injection drug use among our study participants was 21.77 ± 5.65 years. In a Delhi-based study by Gregory Armstrong et al. in 201327, the average age of initiation was lower (15.8 years). This age variation can be explained by the difference in the study population that was targeted by the researchers. Their study was community-based and targeted the hidden group with high injecting behaviour as opposed to our study. Peer pressure was the main reason for injecting behaviour among the majority of our participants, followed by curiosity and fun. This is in agreement with the findings of the study conducted by Samina Farhat et al. in 201520. The pressure to conform (to do what others are doing) can be powerful and hard to resist. A person might feel pressure to do something just because others are doing it. Peer pressure can influence a person to do something relatively harmless or something that has more serious consequences. The negative influence of the peer group is more connected to involvement in risk behaviours28. Daily heroin use in the last 3 months was reported by 94.2% of the participants. In the study by Silvia Tortajada et al. in 20126, the majority of the study participants used injection drugs one or two days a week, and only 16.2% used them every day. Nearly one-third of the participants had a family history of substance use. Another important finding of the current study was friends as the major path of referral. Treating one injection drug user can be the motivation for seeking treatment among other PWID, creating a positive cycle.

In our study, psychiatric comorbidities were found in 88.1% of the participants. This is similar to findings in other studies conducted in other parts of India, such as those by Farooqui et al. and Mohanty et al.29,30, in which 98.6% and 77.5% of participants had psychiatric comorbidities, respectively. This difference in the prevalence can be explained by the difference in the measurement tools used in these studies. Studies from the West have reported a lower prevalence of psychiatric morbidities, 52.7% by Angelo Giovanni M. et al. in 201110 and 43% by Silvia Tortajada et al. in 20126. Approximately two-thirds of our study participants had more than one psychiatric comorbidity. However, this is slightly higher than the number in the study conducted by Farooqui et al. in 202229. This high burden of psychiatric comorbidities requires rigorous assessment of PWID for multiple disorders other than substance use disorders.

Anxiety disorders comprising panic disorder, agoraphobia, social anxiety disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder were found in most of the participants (66.5%). A slightly higher prevalence (71%) of anxiety disorders was also found in a study by Gregory Armstrong et al.22. Other studies had a significantly low prevalence of anxiety disorders6,25. The higher prevalence of anxiety disorders can be explained by the unrest in Kashmir and the COVID-19 pandemic during the study period.

Nearly one-third (39.3%) of the participants had an antisocial personality disorder. This finding was consistent (44%) with those of the study by Robert K. Brooner et al. in 199331. In a study by S. Darke et al.32, community-based methadone patients, prison inmates enrolled in prison methadone programs and prison inmates with no history of heroin use were interviewed to obtain a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) and psychopathy. They reported that 44% of community-based methadone patients had ASPD, which is similar to the findings of our study32. Furthermore, any history of injecting drugs increases the odds of being diagnosed with an antisocial personality disorder by a factor of 21.0133. ASPD poses a major challenge to health care providers, as the outcome remains poor.

Major depressive disorder was found in 17.7% of our study population. A similar prevalence of depressive disorder was found in the studies by Trouiller P et al.7 (21.3%), Margoob MA et al.34, and Mary E. Mackesy-Amiti et al. (25%)7,23. Only 3% of the participants in our study had psychotic disorders. PTSD was found in 8.5% of our study participants, which was in line with the findings by Margoob MA et al.34. These findings could be attributed to local political unrest that causes trauma and discontent.

In our study, suicidality (excluding low intent) was experienced by 29.5% of participants. The study by Iskandar et al.5 showed a prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts ranging from 50 to 93% and 43–87%, respectively. There have been substantial variations in the prevalence of suicidality between studies. Suicidality has been difficult to compare owing to different risk assessment methods employed by different researchers5 and the inclusion of low intent in calculating the prevalence.

In the bivariate analysis, co-occurring substance use of codeine, oral tramadol, and tapentadol and the use of multiple drugs over time by PWID showed a significant relationship with the development of psychiatric comorbidities. Surprisingly, using a combination of opioids at a single point in time protected against psychiatric conditions in people who inject drugs. This finding of polysubstance use and an increase in psychiatric comorbidities in PWID is in line with those in the studies by Fischer et al.35 and Mackesy-Amiti et al.23, in which polysubstance use was associated with psychiatric comorbidities.

Cannabis use was significantly associated with major depressive disorder. This is in agreement with the studies by Daniel Feingold et al. and John Horwood et al.36,37. There is a potential genetic correlation contributing to the comorbidity of cannabis dependence and major depression. Serotonin (5-HT) may mediate such an association, and there is also evidence for specific risk alleles for cannabis addiction36. In our study, cocaine, amphetamine, and inhalant use were positively associated with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Daily heroin intake was negatively associated with psychotic disorders. These findings are similar to those of the study by Trouiller P et al. (2020), in which daily heroin use was negatively associated with major depressive disorder and psychotic disorders in PWID7. The hypothesis of an antipsychotic or modulatory effect of opioids on dopamine or on the neurotransmitter system that controls mood has been suggested38,39,40,41. All substances except amphetamine and daily heroin intake were found to be significantly associated with anxiety disorders.

In the binary logistic regression, younger age was protective against psychiatric comorbidities. This can be explained by the cumulative effect of substances over time on the development of psychiatric comorbidities. This also calls for the need for early intervention among people who inject drugs to prevent the development of psychiatric disorders. Having never been married was also associated with more psychiatric comorbidities. The hypothesis for this finding can be ascribed to a lack of social support. In 1999, Rebecca S. Brienza et al. found that opioid users without a current partner were more likely to be depressed than those with a partner42.

Strengths and limitations

This is one of the first studies from the Kashmir Valley to focus on identifying psychiatric comorbidities in the special group of people who inject drugs. This study used nationally and internationally approved tools for data collection. This study also identified various demographic characteristics and the use of concurrent substances in the development of psychiatric comorbidities among opioid injectors and included patients younger than 18 not previously included in any study. In addition, the prevalence of single and multiple comorbidities not routinely reported in earlier studies was calculated in this study.

This study also has some limitations. This was a single-centre study with a cross-sectional design. This study did not analyse dependence on substances other than opioids. Furthermore, this study included PWID seeking medical help; hence, the results can be extrapolated to this group only.

Conclusions

This study concluded that in addition to injecting opioids, a substantial number of PWID used multiple substances over time. A higher percentage of multiple psychiatric comorbidities was prevalent among PWID who used opioids. Anxiety disorders (panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, agoraphobia and generalized anxiety disorder) were the most frequent psychiatric comorbidities, followed by antisocial personality disorder. The use of other opioids, such as codeine, tramadol, tapentadol and multiple opioids, over time was associated with a higher frequency of psychiatric comorbidities. Furthermore, the concurrent use of other substances, such as tobacco, cannabis, cocaine, inhalants, sedatives and alcoholic beverages, significantly increased the odds of psychiatric comorbidities. Younger age and the use of a combination of opioids were negatively associated with psychiatric comorbidities. Future research should cover all PWID and should also focus on medical comorbidities and the quality of life of PWID with psychiatric comorbidities. The results of this study suggest that physicians treating PWID should be mindful of psychiatric comorbidities and risk factors associated with such conditions during patient care.

Recommendations

This study recommends routine screening of opioid injectors for psychiatric comorbidities. In general, physicians who treat PWID in deaddiction centres should refer PWID for the identification of psychiatric comorbidities to relevant specialists. The treating physician should especially focus on patients with a history of prolonged injection drug use, older patients, those using multiple drugs, and patients who have never been married for referral. Policy-makers should include the mandatory screening of PWID for psychiatric comorbidities in deaddiction programs.

Methods

This study was conducted at the Deaddiction Centre and Addiction Treatment Facility of one of the medical colleges in the summer capital of Jammu and Kashmir, India. This was a single-centre, hospital-based, cross-sectional study that was carried out from March 2021 to August 2022. PWID with a history of injection substance use at least once in the last 3 months25 and who were seeking treatment were recruited in this study. People of all age groups and both sexes were included in this study. PWID were identified by urine drug screening by card tests and injection marks. Terminally ill patients, those suffering from life-threatening illnesses and pregnant females were excluded from this study.

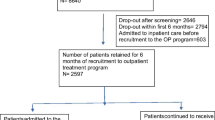

Sample size and sampling procedure

Online Raosoft sample size calculation software was used to determine the sample size43. The sample size for this research was based on the prevalence from a previous study that reported that 67% of PWID have psychiatric comorbidities29. At a 95% confidence interval and a 5% allowable error, the required sample size was 277.

The study participants were recruited using the consecutive sampling method. The researcher began by inviting a single participant, obtaining informed consent, collecting data, and then moving on to the next participant. If the next participant declined to participate, the researcher extended an invitation to a different participant who arrived to seek treatment.

Data collection

The sociodemographic profiles of the participants were recorded on the data collection sheet of the approved national survey on patterns and extent of substance use2. A semi-structured proforma covered questions on paths of referral, age of initiation of opioid injecting behaviour, reasons for injecting opioids and family history of substance use of the participants. In addition, WHO-ASSIST was used to assess the frequency of opioid injections, previous attempts to reduce opioid use, and the presence of co-occurring substance use44. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview-7 (MINI-7)45 was used to ensure uniformity in the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders. The MINI-7 is a short, structured diagnostic interview developed for evaluating the most common psychiatric disorders in clinical and research settings. The various disorders included are depressive disorders, bipolar affective disorders, suicidality, anxiety disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorders, psychotic disorders, eating disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and antisocial personality disorder. It takes approximately 15 min to administer. The MINI-7 is an updated version of the MINI corresponding to the DSM-5. It is the most widely used tool by mental health professionals and health organizations in more than 100 countries. To assess comorbid psychiatric disorders, the MINI- 7.02 was administered to the participants. It should be noted that we excluded suicidality while calculating the total prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities. Participants diagnosed with a mental health disorder were offered psychiatric follow-up in the psychiatric outpatient department (OPD).

The researcher received necessary training on face-to-face interviews from the Department of Psychiatry. All potential participants were approached to participate. The purpose of this study, procedures involved and the voluntary nature of participation were explained to the patients. The confidentiality of the data was assured.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 21, SPSS, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.) was used for data analysis. The data were coded and double checked at entry. The results are presented as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means with standard deviations for continuous variables. Bivariate analysis was carried out using Fisher’s exact test, the chi square test with or without Yates correction and odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals to assess the relationship between sociodemographic characteristics and concurrent use of other substances and major psychiatric comorbidities. Logistic regression was carried out using the ENTER method to identify the variables predicting psychiatric comorbidities. The adjusted odds ratio with 95% CI was calculated and is presented in the relevant tables. A P value of < 0.05 was considered significant for this study.

Ethics statement

The institutional Ethical Committee of SKIMS Medical College Srinagar (IEC SKIMS Medical College) approved the research protocol (protocol no: IEC/43/2021 dated 26th March 2021).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their parents/guardians before the interviews. Research was performed in accordance with local guidelines/regulations and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Participation was voluntary, and the data collected were anonymous.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Desa, U. World population prospects 2019: Highlights. U.N. Dep. Econ. Soc. Affairs 11, 125 (2019).

Ambekar, A. et al. Magnitude of substance use in India. New Delhi: Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India (2019).

Gu, J. et al. Mental health and interpersonal factors associated with HIV-related risk behaviors among non-institutionalized female people who inject drugs who are also sex workers in China. Women Health 50, 20–36 (2010).

Novak, S. P. & Kral, A. H. Comparing injection and non-injection routes of administration for heroin, methamphetamine, and cocaine users in the United States. J. Addict. Dis. 30, 248–257 (2011).

Iskandar, S., Kamal, R. & De Jong, C. A. Psychiatric comorbidity in injecting drug users in Asia and Africa. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 25, 213–218 (2012).

Tortajada, S. et al. Psychiatric morbidity among cocaine and heroin users in the community. Adicciones 24, 201–210 (2012).

Trouiller, P. et al. Daily heroin injection and psychiatric disorders: A cross-sectional survey among people who inject drugs (PWID) in Haiphong, Vietnam. Drug Alcohol Depend. 216, 108334 (2020).

Armstrong, T. D. & Costello, E. J. Community studies on adolescent substance use, abuse, or dependence and psychiatric comorbidity. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 70, 1224 (2002).

Conner, K. R., Pinquart, M. & Duberstein, P. R. Meta-analysis of depression and substance use and impairment among intravenous drug users (IDUs). Addiction 103, 524–534 (2008).

Maremmani, A. G. I. et al. Dual diagnosis and chronology of illness in treatment-seeking Italian patients dependent on heroin. J. Addict. Dis. 30, 123–135 (2011).

Marquez-Arrico, J. E., López-Vera, S., Prat, G. & Adan, A. Temperament and character dimensions in male patients with substance use disorders: Differences relating to psychiatric comorbidity. Psychiatry Res. 237, 1–8 (2016).

Carpentier, P. J. et al. Psychiatric comorbidity reduces quality of life in chronic methadone maintained patients. Am. J. Addict. 18, 470–480 (2009).

Rush, A. J. et al. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in depressed outpatients: Demographic and clinical features. J. Affect. Disord. 87, 43–55 (2005).

Shekhawat, S. Conflict induced displacement: The Pandits of Kashmir. Confl. Trends 2009, 31–37 (2009).

Margoob, A. & Ahmad, S. A. Community prevalence of adult post traumatic stress disorder in South Asia: Experience from Kashmir. Jammu Kashmir Pract. 13, S18-25 (2006).

Miller, K. E. & Rasmussen, A. War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: Bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Soc. Sci. Med. 70, 7–16 (2010).

Silove, D. et al. Effects of recurrent violence on post-traumatic stress disorder and severe distress in conflict-affected Timor-Leste: A 6-year longitudinal study. Lancet Glob. Health 2, e293–e300 (2014).

Steel, Z. et al. Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 302, 537–549 (2009).

Lai, L. Treating substance abuse as a consequence of conflict and displacement: A call for a more inclusive global mental health. Med. Confl. Surviv. 30, 182–189 (2014).

Farhat, S., Hussain, S. S., Rather, Y. H. & Hussain, S. K. Sociodemographic profile and pattern of opioid abuse among patients presenting to a de-addiction centre in tertiary care Hospital of Kashmir. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 6, 94 (2015).

Rather, Y. H. et al. Pattern and prevalence of substance use and dependence in two districts of Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir: Special focus on opioids. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 10, 414 (2021).

Armstrong, G. et al. Association of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation with high-risk behaviors among men who inject drugs in Delhi, India. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 64, 502–510 (2013).

Mackesy-Amiti, M. E., Donenberg, G. R. & Ouellet, L. J. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among young people who inject drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 124, 70–78 (2012).

Chahua, M. et al. Quality of life in a community sample of young cocaine and/or heroin users: The role of mental disorders. Qual. Life Res. 24, 2129–2137 (2015).

Mawiong, A. M., Senjam, G. S., Haobam, M., Singh, N. H. & Khongji, P. A study of psychiatric comorbidities among treatment seeking opioid injectors attending tertiary care teaching hospital, Imphal for a period of 2 years. J. Med. Soc. 32, 174 (2018).

Din, N. U. et al. Socio-demographic & clinical profile of patients with substance use disorders seeking treatment: A hospital based study. Res. Med. Eng. Sci. 7, 808–814 (2019).

Armstrong, G. et al. Quality of life, depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation among men who inject drugs in Delhi, India. BMC Psychiatry 13, 1–11 (2013).

Tomé, G., de Matos, M. G., Simões, C., Camacho, I. & AlvesDiniz, J. How can peer group influence the behavior of adolescents: Explanatory model. Glob. J. Health Sci. 4, 26 (2012).

Farooqui, A. M., Arya, A., Singh, A. & Dalal, P. K. Psychiatric comorbidity, psychosocial problems, and functioning of people who inject opioids: An observational study. Addiction 14, 218–223 (2022).

Mohanty, R., Senjam, G. & Singh, N. H. Psychiatric comorbidities among opioid-dependent patients attending department of psychiatry, regional institute of medical sciences hospital, Manipur. Indian J. Soc. Psychiatry 34, 132 (2018).

Brooner, R. K., Greenfield, L., Schmidt, C. W. & Bigelow, G. E. Antisocial personality disorder and HIV infection among intravenous drug abusers. Am. J. Psychiatry 150, 53–58 (1993).

Darke, S., Kaye, S. & Finlay-Jones, R. Antisocial personality disorder, psychopathy and injecting heroin use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 52, 63–69 (1998).

Dinwiddie, S. H., Reich, T. & Cloninger, C. R. Psychiatric comorbidity and suicidality among intravenous drug users. J. Clin. Psychiatry 53, 364–369 (1992).

Margoob, M. A. et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with substance use disorder: A hospital-based study. Indian J. Soc. Psychiatry 33, 63–66 (2017).

Fischer, B. et al. Illicit opioid use in Canada: Comparing social, health, and drug use characteristics of untreated users in five cities (OPICAN study). J. Urban Health 82, 250–266 (2005).

Feingold, D. & Weinstein, A. Cannabis and depression. In Cannabinoids and Neuropsychiatric Disorders (eds Murillo-Rodriguez, E. et al.) 67–80 (Springer International Publishing, 2021).

Horwood, L. J. et al. Cannabis and depression: An integrative data analysis of four Australasian cohorts. Drug Alcohol Depend. 126, 369–378 (2012).

Déglon, J.-J. & Wark, E. Methadone: A fast and powerful anti-anxiety, anti-depressant and anti-psychotic treatment. Heroin Addict. Relat. Clin. Probl. 10, 47 (2008).

Maremmani, A. G. I. et al. Substance abuse and psychosis. The strange case of opioids. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci 18, 287–302 (2014).

Tenore, P. L. Psychotherapeutic benefits of opioid agonist therapy. J. Addict. Dis. 27, 49–65 (2008).

Schmauss, C. & Emrich, H. M. Dopamine and the action of opiates: A reevaluation of the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia with special consideration of the role of endogenous opioids in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 20, 1211–1231 (1985).

Brienza, R. S. et al. Depression among needle exchange program and methadone maintenance clients. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 18, 331–337 (2000).

Raosoft, I. Sample size calculator. Retrieved from Raosoft.com. http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (2019).

Humeniuk, R., Ali, R., Organization, W. H. & Group, A. P. I. S. Validation of the Alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST) and pilot brief intervention [electronic resource]: A technical report of phase II findings of the WHO ASSIST Project (2006).

Sheehan, D. V. et al. The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry 59, 22–33 (1998).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the dean of research at SKIMS University for supporting this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception, design, supervision and final editing, A.M.G.; Data collection, analysis, writing of the first draft, H.K.; Statistics and final draft, A.B.; Validation, resources, N.D.; Data curation; F.R.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kar, H., Gania, A.M., Bandy, A. et al. Psychiatric comorbidities and concurrent substance use among people who inject drugs: a single-centre hospital-based study. Sci Rep 13, 19053 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45633-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45633-y

- Springer Nature Limited