Abstract

This chapter tracks the awareness and consumption of, engagement with, and attitudes surrounding new, digital, “configurable” cultural forms and practices, using data from surveys conducted across a diverse range of nations. Respondents included English-speaking, online adults in the USA, Canada, Australia, the Philippines, South Africa and the UK. These data are analyzed to examine the correspondences and differences between media consumers living within different cultural, technological and legal regimes. The analysis pays special attention to demographic factors such as age, and geographic divides such as the delta between “advanced economies” and “emerging markets and developing economies.” The data show that these factors have significant, measurable consequences for access to knowledge and cultural participation, in ways that threaten to compound these social inequities in the future. In fact, the data show that user age and national wealth are far greater factors in personal use of digital culture than the size of individual markets, the prevailing copyright law, or the overall level of engagement with digital media among the population at large.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The precipitous growth of Internet adoption around the globe over the past two decades has contributed to profound changes in our cultures and cultural markets, as well as the complex web of relationships among creators, industries and audiences. Yet, these changes take different forms from nation to nation and generation to generation; as science fiction author William Gibson famously observed, “The future is already here—it is just unevenly distributed” (Standage 2001).

One of the most important cultural developments spurred by digital networked technologies has been the emergence of a range of new expressive forms and creative practices. These new forms and practices take advantage of the unique affordances of both production and distribution platforms, specifically: (a) the “cut-and-paste” capabilities for audio, video and photographic media available on the billions of computers, tablets and smartphones in current use; (b) the prospect of a simultaneously massified and customized media experience provided by social media services such as Facebook and YouTube; (c) the “context collapse” (Marwick and boyd 2011) and blurring of the lines between interpersonal and public communication resulting from the convergence of previously discrete social networks onto a common communication infrastructure; and (d) the massive acceleration of the feedback cycle between production, reception and redistribution enabled by these media platforms.

While the cultural and industrial consequences of these changes to the communications infrastructure are diverse and far-ranging, several theorists have proposed analytical frameworks that focus on the shared dimensions of these new expressive forms and practices, as well as the collective social impact of their adoption on a broad, global scale. These include Jenkins’ (2006) theory of “convergence culture,” which emphasizes the new points of common interest and collaboration between artists, industries and audiences; Bruns’ (2008) “produsage” and Ritzer and Jurgenson’s (2010) “prosumption,” both portmanteaus suggesting the blurring of the lines between traditional conceptions of production and consumption; and Lessig’s (2008) term “remix culture,” which critiques a copyright system rooted in the premise of “original” cultural expression and the resulting proprietary corporatism of the global culture industries.

In my own work (Sinnreich 2010), I have used the term “configurable culture,” in order to emphasize the ways in which the logic of networked digital communications has quickly become the dominant organizational regime for cultural, social and industrial institutions around the industrialized world in the twenty-first century. A central aspect of this project has been the collection and analysis of empirical data regarding the awareness, consumption, engagement and opinions of everyday Internet users regarding new cultural forms and practices such as mashups, remixes and video game mods, as well as the role of demographics and other sociocultural factors in shaping these trends. My colleagues and I have found that attributes of respondents, such as age, income, education level, ethnicity and nationality, play a measurable role in shaping how individuals adopt configurable cultures, interact with online distribution platforms and evaluate the ethics of those behaviors and interactions (Sinnreich et al. 2009; Latonero and Sinnreich 2014).

In this chapter, I will examine the results of a recent international survey to evaluate the differences in configurable culture awareness, behavior and attitudes of Internet users across a range of different national media markets and to highlight the ways in which the divergent cultural, legal and economic factors at play in those markets influence engagement with audiovisual media. While all of the nations surveyed were English-speaking and relatively high-population (25 million or more), four of them (the USA, the UK, Canada and Australia) are designated as “advanced economies” and two (South Africa and the Philippines) are designated as “emerging markets and developing economies” by the International Monetary Fund (2018). Along similar lines, the first four countries are typically grouped as belonging to the “Global North” (despite Australia’s location in the southern hemisphere), while South Africa and the Philippines are understood to be members of the “Global South” (despite the Philippines’ location in the northern hemisphere) (Miraftab 2009; Misalucha 2015). These six nations are also geographically diverse, representing populations in four different global regions (North America, Europe, sub-Saharan Africa and Asia/Pacific).

Thus, while this chapter diverges from others in this volume by focusing on larger, rather than smaller media markets, it sheds light on an analogous divide—that between wealthier markets that tend to produce global media, and “developing” ones, which tend to be relegated to the consumption end of the spectrum. Even among English-speaking, high-population nations, there is a center and a periphery, and the differences between these markets in terms of behavior and opinions are stark and instructive.

2 Methods

The survey was fielded in July and August 2017, to online, English-speaking adults in six countries. After using two separate screening questionsFootnote 1 to eliminate false or meaningless data, respondent numbers in each surveyed nation were as follows: the USA (n = 510), Australia (n = 132), Canada (n = 121), the Philippines (n = 139), South Africa (n = 134) and the UK (n = 193). These respondent pools were demographically diverse, in terms of gender (35.5% male, 64.5% female), income (40.7% below $40,000 annual income, 12.6% above $100,000) and education (20.6% with only secondary education, 65.8% with some university-level education and 12.8% with a postgraduate degree).

Initial analyses of these data demonstrated that practices and attitudes surrounding configurable culture vary considerably by age, reaffirming recent findings by Yates et al. (2015) that there is a statistically significant difference, with a large effects size, between digital media usage patterns of those under and over the age of 35. Consequently, for the purposes of this chapter, I have treated the below-35 (45.8% of respondents) and 35-and-above (54.2%) populations of each surveyed nation as analytically distinct.

3 Analysis

3.1 Awareness of Configurable Culture

There were significant divergences in awareness levels of various configurable cultural forms, across both nationalities and age groups. The vast majority of respondents said they are aware of cut-and-paste musical forms like mashups and mixtapes, though young South Africans are disproportionately unaware of mashups, and Filipinos of all ages are far less likely to have heard of mixtapes—a product that depends as much on physical as on digital distribution networks. However, Filipinos of all ages are disproportionately more likely than other respondents to have heard of anime music videos—most likely because, although this is a globally produced and consumed art form, it originated in Asia. Although there are consistent gaps in awareness between older and younger respondents across all categories, the gaps are the greatest for video mashups (with the exception of the Philippines) and video game “mods”—most likely due to the disproportionate time spent on PC gaming among younger adults (Fig. 12.1).

3.2 Consumption of Configurable Culture

While the majority of respondents (especially those under 35) demonstrated awareness of most configurable cultural forms, actual levels of consumption (captured by the question “which of the following have you used or consumed in the last year?”) are far lower, and the gaps between young and old tend to be much greater, especially in categories that may be understood as emblematic of online youth culture, such as anime music videos (consumed by only 2.4% of older UK adults) and video game mods (consumed by only 1.4% of older Australian adults). The Philippines presents an interesting exception, however; although older respondents are consistently less aware of these cultural forms than older ones, those who are aware are much more likely to consume them. In nearly every category, Filipino adults’ consumption levels dwarf those of their contemporaries from other nations. In the case of mixtapes, older Filipinos are nearly twice as likely to have listened to them (25.7%) than younger Filipinos (13.7%) (Fig. 12.2).

3.3 Engagement with Configurable Culture

This study distinguishes between consumption (discussed above) and engagement, which involves a mode of cultural activity that falls somewhere between the traditional modalities of production and consumption. In earlier work (e.g., Sinnreich and Latonero 2014), we distinguished between “consumption-adjacent” practices, such as creating a playlist or a custom radio station, which require relatively little expertise and effort by the user, and “production-adjacent” practices, such as producing a mashup or a remix, which have a much higher bar to entry. Of course, many other configurable cultural activities, such as making a meme or live streaming a concert, fall deeply into the gray area between these polarities and have little similarity to either traditional production or consumption modalities.

This survey queried respondents about a range of different forms of engagement with audiovisual work, from consumption-adjacent to production-adjacent. For musical works, different forms of engagement were adopted at very different rates among respondents from different countries. Americans were by far the most likely to use custom radio programming, such as the services offered by Pandora, iHeartRadio and Apple Music. While this may be due at least in part to availability (Pandora has operated only in the USA since 2017), there must be other factors as well, given that iHeartRadio also operates in Canada and Australia, and Apple Music operates in every nation surveyed.

Although Americans are most involved in the consumption-adjacent musical practices, younger Australians, South Africans and Britons, as well as older Filipinos, are much more likely to say that they engaged in production-adjacent activities, such as creating sample-based music. Many of the gray area practices I surveyed are viewed from an industrial and legal standpoint as copyright infringement—in large part, no doubt, because of the mismatch between a legal system crafted in the era of mass media and the much broader and more flexible affordances of digital communications platforms (Patry 2011). These gray area practices are most common among Filipinos and South Africans of all ages, who ranked first and second for sharing files online, “stream ripping” (saving a streaming audio file as an MP3) and live streaming a concert from a mobile phone (Fig. 12.3).

Similar patterns emerged from the question regarding engagement with video-based media. Older American adults were by far the most heavily engaged in the consumption-adjacent practice of using a digital video recorder (DVR) to save and retrieve televised content (although South Africans led among younger adults). As in the case of musical practices, Filipinos and South Africans in both age categories led the gray area (and potentially copyright-infringing) categories of file sharing, stream-ripping and video uploading, by exceedingly wide margins. When it came to the production-adjacent practice of remixing video, engagement levels among younger adults hovered around 8–10% in most nations (except for Canada, where the rate was only 1.9%), while most older adults had little or no experience, except for the Philippines, where nearly a quarter of older adults said they’ve remixed video—a staggering figure double the rate of those who said they’ve used a DVR.

In short, nations with higher levels of income, and stronger copyright enforcement regimes, appear to have a greater overall engagement level with audiovisual media at the consumption end of the spectrum, and nations where fewer people have access to legal sources of online content distribution tend to have a higher degree of involvement in gray area practices that skirt the lines of legality. In every nation, the production-adjacent end of the spectrum, which is characterized by making sample-based media, tends to be disproportionately a youth practice, with the notable exception of the Philippines, where older adult engagement in remixing dwarfs that of their younger compatriots (Fig. 12.4).

3.4 Civic Engagement via Digital Media

Engagement with audiovisual forms of configurable culture seems to dovetail with civic and political engagement via digital media. In most of the categories of online civic engagement we measured in the survey, levels of use were far higher among Filipinos and South Africans than among those from other nations. For all nations surveyed, the age gap for digital civic engagement was much smaller at the consumption end of the spectrum; the number of older adults who shared news stories via social media, or signed up for alerts from news Web sites and applications, was close to the number of younger adults in every country except the UK (where older adults demonstrated a much lower level of engagement with audiovisual media than their younger compatriots). The Philippines, where older adults were more likely than the young to engage in activities like stream ripping and uploading, was the one nation in which older adults were also more likely to engage in digital civic activities such as signing up for news alerts, signing online petitions and participating in real-world political action organized via the Internet. In nearly every category, Canadians were either the least or among the least civically engaged, echoing their relatively low engagement levels with audiovisual configurable culture (Fig. 12.5).

3.5 Opinions on Ethics and Legality

In addition to surveying respondents regarding their awareness, consumption and engagement with configurable culture, I asked them to share their opinions about the ethics and legality of configurable cultural practices such as mashups and remixes. As Raz (2009) argues, a legal system must necessarily be rooted in the ethical values embraced by the culture that gives rise to it; in his words, “legal theory attempts to capture the essential features of law, as encapsulated in the self-understanding of a culture” (p. 98). However, as I have demonstrated in previous publications (Sinnreich et al. 2018), there is an enduring gap between what people think is ethical and what people believe should be legal in the case of configurable culture; in other words, the novelty and social stigma attached to these emerging forms of expression undermine people’s support for a legal system that would enable them to flourish.

This gap between ethical and legal imaginaries can be measured empirically using survey data. Specifically, one question asks, “To what extent do you consider mash-ups and remixes ‘original’?” Respondents had a choice between saying that: (a) all remixes and mashups are unoriginal; (b) some are original and others are unoriginal; (c) all are original; and (d) prefer not to answer. As I have demonstrated in earlier work (Sinnreich et al. 2009), while most media consumers don’t think explicitly in ethical terms, their ethical thinking is encoded in the form of aesthetic judgments regarding the “originality” of a work; hence, a mashup deemed sufficiently “original” may be seen as ethical, while one deemed “unoriginal” may be deemed unethical. This syllogism is recognized explicitly in copyright law, as well; in the USA, for instance, case law holds that “original, as the term is used in copyright, means only that the work was independently created by the author (as opposed to copied from other works), and that it possesses at least some minimal degree of creativity.”Footnote 2

Along similar lines, the survey captured respondents’ legal opinions by asking, “In your opinion, how should copyright apply to mash-ups and remixes?” For this question, possible responses included: (a) all mashups and remixes made without permission of the “original” author should be illegal; (b) some uses should require permission and others should not; (c) all remixes and mashups should be made without the need for permission; and (d) prefer not to answer. In order to demonstrate the gap between ethical and legal opinion, we may compare the percentage of respondents who said, on the one hand, that configurable culture is always or sometimes original with the percentage who said that it should always or sometimes be legal.

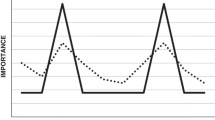

The data show that, in keeping with my previous research, there is a consistent gap across all nations and age groups between the perception that configurable culture may sometimes or always be original, and the expectation that it may sometimes or always be legal. In other words, respondents’ support for the ethical validity of configurable culture was not matched by their expectations of support from the legal system for these practices. Furthermore, younger respondents were far more likely than older ones to believe that configurable culture could be both ethical and legal. The only exception to this trend was older Filipino adults, who were more likely than their younger compatriots to say that configurable culture could be original (and therefore ethical). This makes sense in light of the data discussed above, showing that engagement with some production-adjacent configurable cultural forms—such as stream ripping, remixing and uploading—are more common among older than younger Filipinos.

Overall, the gaps between ethical and legal opinions, and the level of support for configurable culture across and between national populations, were fairly consistent and seem to have little to do with the differences between national legal systems, or levels of awareness, consumption and engagement among the populations in question. For instance, both the USA and the Philippines have broad “fair use” rules in their copyright laws, which cover many “transformative” uses of cut-and-pasted content, but the other four nations have more restrictive “fair dealing” rules, which tend to be much more restrictive, in a configurable cultural context (Aufderheide and Jaszi 2018). Yet, attitudes about the legality of these practices were more similar between the USA and UK, and between the Philippines and South Africa (in the case of older adults) than between nations that share the same style laws. This suggests that perhaps other factors—such as cultural values—play at least as causative a role in shaping legal expectations as the actual letter of the law (Fig. 12.6).

4 Conclusion

In this chapter, I have analyzed survey data regarding levels of awareness, consumption, engagement and attitudes with respect to configurable cultural forms and practices, such as remixes, mashups and video game mods, as well as peer-to-peer redistributive practices, such as live streaming and file sharing. The data illuminate some differences between age groups and nations, yet also raise many questions. Patterns of ethical and legal opinions seem to have little to do with the size of individual markets, the prevailing copyright law, or the overall level of engagement with digital media among the adult population. Instead, it seems that one of the principal differentiators is between so-called advanced and developing economies. Users in wealthier nations like the USA tend to be more likely to participate on the consumption-adjacent end of the spectrum (engaging in practices such as listening to custom radio and time-shifting via DVR), while users in poorer nations like the Philippines and South Africa are far more likely to engage in production-adjacent practices like remixing, as well as gray area practices like file sharing and stream ripping. This suggests that media consumers in these markets, by virtue of their institutional relegation to being consumers of commercial content from the Global North, use digital platforms as a way to reestablish some ownership stake and participatory role in global cultural flows. Collectively, these data suggest that we must understand economics as a principal driver of adoption patterns for new media platforms and practices, with an equal or greater causative role relative to legal and cultural factors.

Notes

- 1.

“What shape is planet Earth?” and “Have you responded accurately to the questions above?”

- 2.

Feist Publications v. Rural Telephone Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340 (1991).

References

Aufderheide, P., & Jaszi, P. (2018). Reclaiming fair use: How to put balance back in copyright. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bruns, A. (2008). Blogs, Wikipedia, second life, and beyond: From production to produsage. New York: Peter Lang.

International Monetary Fund. (2018). World economic outlook: Challenges to steady growth. https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/WEO/2018/October/English/main-report/Text.ashx. Accessed June 22, 2019.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York: NYU Press.

Latonero, M., & Sinnreich, A. (2014). The hidden demography of new media ethics. Information, Communication & Society,17(5), 572–593.

Lessig, L. (2008). Remix: Making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy. London: Bloomsbury.

Marwick, A. E., & boyd, d. (2011). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society,13(1), 114–133.

Miraftab, F. (2009). Insurgent planning: Situating radical planning in the global south. Planning Theory,8(1), 32–50.

Misalucha, C. G. (2015). The challenges facing the global south: Perspectives from the Philippines. Bandung: Journal of the Global South,2(1).

Patry, W. (2011). How to fix copyright. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Raz, J. (2009). Between authority and interpretation: On the theory of law and practical reason. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ritzer, G., & Jurgenson, N. (2010). Production, consumption, prosumption: The nature of capitalism in the age of the digital ‘Prosumer.’ Journal of Consumer Culture,10(1), 13–36.

Sinnreich, A., Latonero, M., & Gluck, M. (2009). Ethics reconfigured: How today’s media consumers evaluate the role of creative reappropriation. Information, Communication & Society,12(8), 1242–1260.

Sinnreich, A. (2010). Mashed up: Music, technology, and the rise of configurable culture. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

Sinnreich, A., & Latonero, M. (2014). Tracking configurable culture from the margins to the mainstream. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication,19(4), 798–823.

Sinnreich, A., Forelle, M. C., & Aufderheide, P. (2018). Copyright givers and takers: Mutuality, altruism and instrumentalism in open licensing. Communication Law and Policy,23(3), 197–220.

Standage, T. (2001, October 13). Peering round the corner. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/special-report/2001/10/13/peering-round-the-corner. Accessed June 22, 2019.

Yates, S., Kirby, J., & Lockley, E. (2015). Digital media use: Differences and inequalities in relation to class and age. Sociological Research Online,20(4), 1–21.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sinnreich, A. (2020). Configurable Culture in Wealthy and Developing Markets: A Comparative Cross-National Perspective. In: Szczepanik, P., Zahrádka, P., Macek, J., Stepan, P. (eds) Digital Peripheries. Springer Series in Media Industries. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44850-9_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44850-9_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-44849-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-44850-9

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)