Abstract

Over the past decade or so, the quality of the evaluation note written by a spiritual care provider has been a major issue in debates about accountability and the quality of interdisciplinary collaboration. This article advocates the adoption of our two models of notes: ‘the note following a meeting with a user’, generally used in acute care, and ‘the note following a meeting with a relative’, generally used in long-term care, in cases where a patient can no longer express himself or herself. These two charting models were developed on the basis of the RESS (‘Markers for Spiritual Care Assessment’) assessment tool recently developed at the Centre Spiritualitésanté de la Capitale-Nationale (CSsanté), and their usefulness and applicability were assessed in a research study. The note models presented in this article are inspired by the vision of spirituality that underlies our work accompanying patients and informed the development of the RESS. We found that the clinical benefits of streamlining an evaluation and note-writing model are a major step forward in a profession that has been rapidly evolving in Quebec in recent years.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Background

In the health system, the user’s social and health-care record is, so to speak, the container in which all relevant information about the professional services the user has required and received is kept. It is an essential tool, and one of its key functions is to promote communication between all those involved in the patient’s treatment. In accordance with the Organization and Management of Institutions Regulation/Règlement sur l’organisation et l’administration des établissements in Quebec, a note is written each time some form of professional action is taken;Footnote 1 it is the ‘preferred instrument for demonstrating prudent and diligent professional conduct that meets ethical and civil obligations’.Footnote 2 The health-care record gives the various persons involved a better understanding of the user’s situation whilst ensuring continuity and completeness of care and services.

In Quebec, spiritual care services receive their funding following the compilation of ‘units of measurement’. The types of spiritual care intervention that qualify as units are listed in a document produced by the Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux (MSSS) in 2002. For each unit of measurement reported, there must be a note on file.Footnote 3 From 2003 onwards, CSsantéFootnote 4 introduced the practice of ʻnote to file’ into its institutions. At the time, this was a major step in the development of the profession and an indication of the importance that providing accountability in spiritual care activities would assume in the years to come.

In 2008 we wrote a guide to support spiritual care providers with this new task.Footnote 5 Over several years of using this guide, we have identified two weaknesses in our overall assessment process and in our methods of writing the note to file: (1) there was considerable variation in the way things were done in our own institutions; (2) the language used was sometimes too imprecise for other professionals. Moreover, more generally, the context in which our practice evolved had changed profoundly. As elsewhere in the world, the position of spiritual care professionals has changed over the course of recent decades. We have witnessed a major development: a pastoral paradigm, in which interventions took place in connection with a church or religious tradition, has moved towards a biomedical paradigm (Rumbold 2013).

In Quebec, this new situation can be seen in particular in the changes made in job titles by the Ministry of Health and Social Services: until the 1960s spiritual care professionals were known as chaplains (aumôniers), and then they became pastoral facilitators (animateurs de pastorale) and then, in 2011, spiritual care providers (SCPs) – intervenants en soins spirituels (ISS) . Whilst integrating the richness and diversity of spiritual and religious traditions, the profession has had to state the purpose and objectives of intervention autonomously, i.e. without any reference to a particular church.Footnote 6 Under this new model, intervention practices tend to be carried out and assessed in a context of interdisciplinary collaboration, hence the need to develop language that is intelligible and meaningful to other members of the health-care team.

Particularly following the change of the profession’s name in 2011, work has been undertaken to further improve the practices associated with writing notes. We therefore worked on improving the practices involved in writing notes to file, initially developing an assessment tool, which was agreed upon by all SCPs at CSsanté. This gave rise to a further tool, Repères pour l’évaluation en soins spirituels (RESS) (Markers for Spiritual Care Assessment), on the basis of which a guide for writing notes to file was created.

This document presents the key elements in the practice of writing notes to file commonly applied at CSsanté. There are two main parts: the first, conceptual in nature, presents the RESS tool and the spiritual vision on which it is based; the second, practical in nature, presents the two guides used to write notes, both the assessment/intervention noteFootnote 7 generally used in the short term and the assessment/intervention note employed when users can no longer express themselves.Footnote 8

2 Concepts

As mentioned above, the first part presents the RESS assessment tool and the spiritual vision which underlies it. This conceptual section also sets out how notes to file are written.

2.1 Markers for Spiritual Care Assessment (RESS)

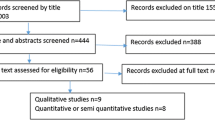

The RESS tool was developed in a three-stage approach: (1) a literature review (2013–2014), which allowed us to identify the main elements which would form the basis of the first working draft; (2) a pilot of this first draft, carried out by CSsanté in the light of the SCPs’ clinical experience Footnote 9 (2014–2015); and (3) validation of the draft tool, by conducting research designed to assess its applicability,Footnote 10 carried out with about 40 SCPs working outside of CSsanté (2016–2017). Figure 1 presents the tool in its current form.

When designing the tool, we used the notion of ʻmarkers’ (repères), which allow us to identify the main themes that can be raised with patients during an assessment meeting. The Larousse dictionary defines ʻrepère’ as that which makes it possible to identify something in a whole, to locate something in time and space. Thus, when recalling and analysing a meeting, the SCPs can use the markers to help them identify the key elements of the encounter. The markers provided in our tool are four topics which may be addressed at the outset by the patients: beliefs and practices, hopes, relationships and values/commitments.Footnote 11 We were already familiar with the STIV tools ,Footnote 12 developed and used in Switzerland in particular, and ST-VIAR,Footnote 13 developed as well as used in Quebec and taught as part of the initial training recognized by the l’Association des intervenants et intervenantes en soins spirituels du Québec (AIISSQ ). As Fig. 1 shows, this tool distinguishes itself from STIV and ST-VIAR in envisaging meaning as a transversal element. In fact, our clinical experience has led us to consider meaning as a series of questions and reflections which generally emerge in close connection with the four key markers. We have also placed a circle at the centre of our diagram bearing the words ʻtranscendent experience ’. This expression, borrowed from Louis Roy (2014), relates to a patient’s capacity or potential to evoke indications of a transcendent experience.Footnote 14 In our diagram, the circle also represents what the spiritual care interventions aim to achieve.

We pursued three objectives in developing the tool: (1) to provide the SCPs with a practical and flexible tool involving markers which would aid them in their assessment work; (2) to present in attractive and concise visual form our understanding of spirituality in the context of illness; and (3) to facilitate and harmonize the writing of notes to file.

2.2 Spiritual Vision Underlying RESS

The assessment tool derives from our spiritual vision and our understanding of different expressions of spirituality during illness. We present this vision in the different points below.

We adhere to the tripartite or ternary anthropological vision which sees human beings as comprising three dimensions: the physical, mental and spiritual. This position is inspired in particular by the writings of anthropologist Michel Fromaget (2007, 2008a, b, 2009) but can also be found amongst other writers: Ugeux (2001), Rosselet (2002), Zundel (2005), Kellen (2015), De Lubac (1990), de Hennezel (1997, cited in Fromaget, 2007), Bryson (2015), etc. Tripartite anthropology is closely related to the holistic vision (bio-psycho-socio and spiritual) of human beings proposed in the Quebec health network, in particular in the field of palliative care. In subscribing to the fact that a human being comprises three dimensions, we assume that a person suffering physically is also affected mentally and spiritually. In the same way, if a person is suffering spiritually, the other dimensions of their life are most likely affected as well.

2.2.1 Spiritual Dimension: Access to the World of the Essence

The spiritual dimension makes direct reference to the word ʻspirit’. With reference to Maître Eckhart, Fromaget (2007) indicates in his work Naître et mourir (Birth and Death) that we cannot comprehend what the spirit is if we have not yet experienced it ourselves. Despite the difficulties involved in objectivizing the spirit, we decided to present this dimension as an ʻopenness’ to the world of essences (Fromaget 2007)Footnote 15 which can be accessed via contemplation. Several authors (Fromaget 2007, 2008a, b, 2009), Kellen (2015), Zundel (2005) and Roy (2014) write about the possibility for all human beings, regardless of their beliefs, to have one or several spiritual or transcendent experiences.Footnote 16 Spiritual life is thus seen as a potential for experience or as a potential for transformation, which appeals to the freedom of each individual.Footnote 17 Pargament (2007) proposes the term ʻsearch for the sacred’ to talk about this spiritual dimension. The word ʻsacred’ is associated with concepts of God, the Divine, transcendent reality, etc. Spiritual life can thus be considered as potential and as a search or quest .

2.2.2 The Transcendent Experience

As mentioned above, the idea of the transcendent experience is key to our RESS model. This expression is borrowed directly from Louis Roy (2014), the title of one of his works being Transcendent Experiences: Phenomenology and Critique. We found that this approach was compatible with the literature which had inspired us up to that time. Roy describes a transcendent experience as:

Il s’agit d’une appréhension – c’est-à-dire d’une sorte de conscience (awareness), de connaissance intuitive qui capte l’attention d’une personne ou d’un groupe parce qu’elle est véhiculée par une sorte de sentiment spécial. Le sentiment colore notre réponse à quelque chose qui apparaît immense. Lorsque nous prenons contact avec une quantité ou une qualité infinie, nous pouvons avoir l’impression que cette dimension déborde notre vie ʻnormale’, qu’elle ne saurait être contenue artificiellement dans les limites familières et qu’elle commande donc un respect profond. (Roy 2014, 15).

This idea of an experience which goes beyond normal life is referred to by other authors but characterized in a different way. Roy (2014) gives several examples: spiritual experience, peak experience, cosmic consciousness, religious experience, sign of transcendence, etc. The central circle of our diagram therefore designates both the possibility of discerning, in the patient’s discourse, signs of a possible experience of transcendence and the intention of the intervention itself. The four basic markers can be ‘heard’ by other professionals (social worker, psychologist, nurse in particular), because they are like vestibules through which one must move in order to enter the person’s inner universe. The ability to recognize and accompany the person by listening to the richest experiences of his or her life (what we call ‘experience of transcendence’) and the questions of meaning that are related to it is a skill that essentially falls within our field of intervention and our formation .

2.2.3 An Experience Recognized by Its Fruits

For many authors, the spiritual or transcendent experience can be seen in the fruits that it bears. Fromaget (2008a) highlights this: ‘Just one solution remains, therefore: to appreciate the depth of the experience by its impact, by the fruits that it bears. And the idea of fruit is an excellent one here, provided that the source of the fruit is unambiguous’ (Fromaget 2008a, 5). What are these fruits? Fromaget is basically talking about the fruit of the spirit as described in Paul’s Letter to the Galatians 5, ‘love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control’. Roy (2014), meanwhile, refers to other fruits: the disappearance of fear and the establishment of profound peace; the acceptance of death and the absence of distress; serenity, peace which lasts for hours and days; and power and creativity. Even if, during a spiritual experience, the outward world changes in appearance, this does not mean that the world itself changes but that it is perceived at a different level (Fromaget 2008b, 6). Didier Caenepeel (2017) in his study of the work by Éric-Emmanuel Schmitt, Oscar et la Dame Rose, gave a good example of this reality in a conference at CSsanté in Quebec in 2017. He referred to the possible fruits arising from the support given to a young boy in palliative care. The reality of approaching death remains, but the child’s perception of the absurdity of this reality changes, allowing him to experience a certain degree of peace and to live his final days better. We had these fruits or signs in mind when we placed at the centre of our RESS model ‘the transcendent experience/signs in which it is manifest’, examples of things which outwardly reveal a possible experience of this type.

2.2.4 Crisis as a Path to a Transcendent Experience

We recognize three main paths which can lead to a transcendent experience : the emotion of love, wonder in the face of beauty and a third, which is crucial in the field of health, the crisis or approach of death (Zundel 2005; Kellen 2015; Fromaget 2008a,b). In the hospital environment, people often experience a difficult moment, and this is a moment in which those providing support can ideally listen out for the possibility of such an experience and be aware of it. In fact, ‘[…] major transitions and life crises […] reveal the deepest dimension of life. Similarly, loss, accident, injury, trauma and disaster can push people to confront the finitude and precariousness of their lives and direct them to look beyond their immediate worlds’ (Pargament 2007, 66). Indeed, considering the crisis patients might experience, spiritual support in the health network is particularly appropriate. The crisis often creates a nodal point which can affect the inner life of the sick person. Marin (2013, 15), talking about the ordeal of illness, describes the crisis well: ‘for some, it is the experience of radical change, the terrible discovery that there is a strangeness at the very heart of intimacy. It requires nothing less than a redefinition of the self’. RESS was developed with this in mind. Our vision of spirituality is closely linked to the ordeal of illness and the suffering it can engender .

2.2.5 A Process…

When talking about the spiritual dimension of human beings, many works focus on the meaning and ultimate aim of human existence. The spiritual life is therefore considered not only as all the elements which can be objectified but also as a process or dynamic experience (Rumbold 2013; Waaijman 2006a). Bryson remarks on this issue: ‘The other point about spirituality is that it evolves as a person’s life experiences accrue. Spirituality is a process rather than an event’ (Bryson 2015, 92). Indeed, a person can experience intense moments of suffering or even of spiritual distress, which then disappear and make way for moments of peace and hope (transcendent experience), or their illness may destroy their sense of peace and tranquillity, leading them to see the ordeal they are experiencing as something absurd… The crisis often gives rise to change in a person’s inner life (Waaijman 2006b). In providing support at this time, SCPs are witnesses to this process. The assessment model reflects this dynamic process, signaling that the intended aim is always to achieve peace and hope (circle at the centre of the illustration); however, during the development of the illness, the patient may in fact oscillate between feelings of well-being and spiritual suffering. We considered this aspect by focusing on the displacement – the movement, represented by the gradation of colours – between the four basic landmarks and the experience of transcendence through meaning. Spiritual life is presented as a process of transformation (sometimes slow, sometimes fast, sometimes surprising), of change and searching (Pargament 2007), in particular in the way of seeing or perceiving what occurs, of experiencing the crisis.Footnote 18

2.2.6 ʻTracking the Theological’

Underlying our model is the conviction that the highest spiritual realities are expressed in the ordinary words a person usesFootnote 19 and that the SCP essentially ʻhears’ the way in which each patient makes sense of the crisis they are experiencing in their everyday speech (each person makes sense of their experience on the basis of a number of sources) (Rumbold 2013). The expression ʻtracking the theological’ (Dumas 2010, 200) corresponds well to this situation. It refers ‘to the subtle presence of God at the heart of the world, a presence-absence that is impossible to define or categorize. The theological is elusive, but can nonetheless be found in the nooks and crannies of everyday life’. It is precisely this idea which underlies our vision of spirituality and our assessment tool. The four key markers on which the tool is based merge visually with meaning and the transcendent experience to show that spiritual life can generally be seen in the questions and reflections (the experience) that emerge from the patient’s daily life and that these can attain profoundly spiritual depths.

3 Note-writing Guides

This part gives a practical description of the two guides,Footnote 20 each containing a model plus explanations for writing notes: both the assessment/intervention note generally used in the short term and the assessment/intervention note employed when users can no longer express themselves.

3.1 Assessment/Intervention Note

The assessment/intervention note is structured directly on the RESS assessment tool shown in Fig. 1. We call this an assessment/intervention note because an assessment meeting often includes an intervention. Figure 2 shows a general model for writing this kind of note, i.e. the way in which it is set out.

Each of the points in the diagram in Fig. 2 is presented below as they appear on the patient evaluation form with an SCP.

3.1.1 Context of Assessment/Intervention

3.1.1.1 Reason for Request

In this section, the SCP indicates whether it is a presentation/evaluation visit or a visit following a reference. If it is a reference, the SCP indicates the reason. The SCP also records the receipt of consent from the user or family member (Fig. 3).

3.1.1.2 Patient’s Condition

The SCP indicates here what he or she perceives of the patient’s conditionFootnote 21 and notes whether a relative or relatives are present (Fig. 4).

3.1.1.3 We also document the sociodemographic data (Fig. 5)

3.1.2 Exploring Markers

In this section, the SCP briefly describes how they understand the situation on the basis of the four key markers.Footnote 22 This can be done in one or two sentences, summarizing what seemed significant and relevant to them during the meeting. In this section, the SCP may report facts, topics or themes addressed by the user, where appropriate recording some of their words directly, so the SCP can clearly demonstrate what they have understood of the patient’s experience on the basis of the key markers. It is preferable not to record anything next to a marker if little was said regarding this subject. Besides the four key markers, in this section we have included the option of noting elements linked to what is referred to in the RESS as the transcendent experience (Roy 2014).Footnote 23 The ability to listen and then converse with a patient around such an experience is a fundamental part of his spiritual life. As indicated in the section Spiritual Vision Underlying RESS (cf. Sect. 2.2), the transcendent experience can be expressed especially when the patient recalls rich experiences in their life that have generated feelings of peace and tranquillity. We believe that referring to these experiences on the basis of the support marker is very important in professional analysis and writing.

3.1.2.1 Beliefs/Practices

-

Adherence to multiform currents or ideas, often from particular cultures, situated in a continuum that can go as far as a transcendent faith that engages a whole life

-

Practices and behaviours generated by beliefs

-

Individual or collective manifestations

3.1.2.2 Hopes

-

Ability/incapacity to project into the future (in the present life)

-

What one can see ahead (possibilities/deadlines)

3.1.2.3 Relationships

-

Relationships between people and their links and influences

-

Impact of the disease on past and present relationships

-

Major relational and emotional issues (love, conflicts, forgiveness, etc.)

3.1.2.4 Values/Commitments

-

What mattered, what had weight in life, the ethics of the person

-

The implementation of values in a particular field of commitment

-

Values and commitments that persist or change

3.1.2.5 Transcendent Experience Shared by the User

-

Emergence of a new being

-

Feeling of strength and courage, peace and communion, elevation, presence and liberation

-

Sensitivity to beauty and love

-

Disappearance of fear and distress

-

The feeling of being loved by God, the power to hope

-

-

The experience of transcendence may manifest itself gradually in the person’s history or suddenly and unexpectedly .

3.1.3 Professional Analysis/Opinion

In this section, the SCP can go through a series of steps which make it easier to identify the information in what they have heard and noted down. This important analytical stage helps the SCP to form a professional opinion about the patient’s state and subsequently to draw up an intervention plan.

There are two parts to this section. Firstly, the SCP identifies a support marker and an obstacle markerFootnote 24 along the user’s personal path. The SCP then offers a synthesis of his opinion using the concepts of spiritual well-being, discomfort and suffering.Footnote 25

3.1.3.1 Identifying a Support Marker and an Obstacle Marker Along the User’s Personal Path

The SCP , recalling the key aspects of the meeting, identifies one or more support marker and one or more obstacle maker. The support marker is that which seems to give the patient strength and reassurance during their illness. The obstacle marker is that which seems to cause the patient the most suffering and difficulty during the ordeal they are undergoing (Fig. 6).

3.1.3.2 Summary and Professional Opinion Based on Analysis Model

The SCPs offer here a synthesis of their professional opinion using the three concepts of spiritual well-being, discomfort and suffering. In order to refine the note and enlighten the care team about their opinion, they may check off some meaningful elements within the selected field. For this step, the SCP can refer to Appendix B, which gives the opportunity to refine its analysis (Fig. 7).

3.1.4 Intervention Conducted (Where Appropriate)

Where appropriate, the SCPs will check one of the interventions. They also note any effects observed on the patient or family members (Fig. 8).

3.1.5 Follow-Up and Support Plan

In this section, the SCP records whether a follow-up meeting is necessary, depending on the focus of the intervention (Fig. 9

).

3.1.5.1 Support Plan

If there is a follow-up, the SCP indicates the objective(s) of this possible intervention by checking or labelling its own objective(s) in the ‘Other’ sections (Fig. 10).

3.1.6 Consent to care

For ethical and legal reasons, the SCP confirms in this section that the user has consented to the meeting and to any possible follow-up work (Fig. 11).

3.2 Note to File When Patients Can No Longer Express Themselves

The diagram in Fig. 2 can be used when the SCP is able to communicate directly with the patient. In some circumstances this is not possible because many patients can no longer express themselves as a result of dementia or some other disability (e.g. aphasia). In Quebec, such clients are often resident in a long-term care establishment (centre d’hébergement de soins de longue durée [CHSLD]) and pose a particular challenge for spiritual care provision. The support of a community of helpers and carers is necessary to recognize their communication difficulties. Indeed, sound knowledge of the patients’ background will ensure that patients in long-term care establishments can live in accordance with their values, beliefs and the meaning they have given to their lives. Making an assessment and recording it in a note to file is essential, but this can only be done with the help of a relative or close friend who provides the information necessary in the support process.Footnote 26

Figure 12 shows a model for drawing up the note to file for patients who can no longer express themselves. This model is similar to that in Fig. 2, but the fact that the patient is known via an intermediary is taken into account throughout, and the note reflects this (Fig. 12).

Below we explain in detail each of the points in Fig. 12.

3.2.1 Context of the Evaluation

Figure 13 presents the elements that are considered in the context of evaluation for patients who can no longer express themselves.

3.2.2 Exploring Markers

In this section, the SCP describes what they hear during the meeting with the patient’s close family member or friend (see Sect. 3.1.2).

3.2.3 Professional Analysis and Opinion

In this section, the SCP picks out one support marker and one obstacle marker (Fig. 14

). This analysis is important as it forms the basis for determining which interventions should take place with the patient.Footnote 27 The SCP takes into account the support marker in order to maintain the resident in the continuity of his history (which made sense) by promoting moments of comfort, peace and joy. The obstacle marker is taken into account by the SCP in order to promote, despite this suffering (which did not make sense), trust, forgiveness, hope, etc.

3.2.4 Orientations/Follow-up/Plan

In this section the SCP indicates what he or she considers appropriate as future directions for this patient. If follow-up is required, he or she indicates what he or she plans to do as an intervention plan with this patient (Fig. 15

).

3.3 In Addition… Sensation and the Transcendent Experience

Sometimes patients, their relatives or close friends might say something about their sensations (relating to the five senses). In some cases, it is difficult for the SCP to establish a link with one of the four key markers. However, it is very important, in our opinion, to be alert to these statements, which provide important information regarding sensation, which is one of the main dimensions of our transversal reference marker, meaning. Here are some examples of how this can be expressed in a patient’s speech. These elements of sensation can be indicated in the ‘values/commitments’ or in ‘experience of transcendence’ markers. They are privileged forms of spiritual support.

Examples:

-

Yesterday I watched a magnificent sunset from my room.

-

I smelt the roses that my son-in-law brought me: they were wonderful.

-

I still enjoy the taste of good food.

-

This music soothes me.

-

On my travels, the warm sand gave me a sense of freedom.

3.4 Impact on the SCP and Care Team

The RESS tool has allowed us to formalize the assessment process and serves as a basis for drawing up note-writing guides setting out clear steps in the process. The new Quebec model of recording spiritual care has several benefits for our profession; in particular, it helps to refine the clinical assessment process. Indeed, the inclusion of markers encourages the SCP to review the assessment meetings by asking a number of fairly open questions which provide relevant guidelines for making an assessment. We have observed that the SCP develops a better understanding of the patient’s experience through this process and thus improves their reporting activities as a whole. Finally, our clinical workshops, which aim at reviewing our support methods, have benefited both from the RESS assessment tool and from this new way of writing the note to file.

The tool also fosters interprofessional dialogue. In fact, the well-defined structure and sequencing of the notes facilitates comprehension, speed of reading and the retention of information in the medium term. At the same time, the medical and nursing staff are better able to understand the service we provide, and information can be more easily passed on. Finally, we are convinced that a well-conceived process for assessing and writing notes to file promotes a more complete understanding of the patients, which can only serve their well-being and the quality of their stay in hospital .

4 Conclusion

In the sixteenth century, Ignace de Loyola recalled that one who determines little understands little and helps even less (De Loyola 1991, 647).

It is in this spirit that we have sought to improve, in recent years, our processes for preparing the note on file. In particular, we focused on the evaluation note, which is crucial in the development of the care plan. A lot of effort has been put into making it as accurate as possible so that it can fulfil its purpose: to help!

The systematic writing of the spiritual care note is still a very new practice in Quebec – it’s barely 15 years old! Even today, it still presents many challenges, the most important of which is inherent to our profession. Indeed, spirituality remains a complex and extensive notion for which there is no definition shared by the entire scientific community. Hence the difficulty of developing a writing framework that is flexible enough to allow us to record our assessment in relation to our vision of spirituality and that is structured enough to be read by the interdisciplinary team in a user-friendly and supportive manner.

In the work of the spiritual care provider, the note on file constitutes a structuring practice that reflects the content of the interventions carried out but also the meaning of spiritual accompaniment that has emerged over the years. We believe that the practice of writing notes will continue to challenge our profession by regularly forcing us to rethink our ‘theology’ and what we convey as a vision of spirituality in a secular and demanding context in terms of the quality of accountability.

Notes

- 1.

These are articles 17 to 28 of the ʻAct Respecting Health Services and Social Services, the Organization and Management of Institutions Regulation’ (see no 53); the ʻRèglements sur la tenue des dossiers de certains ordres professionnels’ and, in a supplementary capacity, the ʻAct on access governed by the content, use and access to files held by health institutions’. For example, Article 50 of the ʻOrganization and Management of Institutions Regulation’ stipulates that ‘every institution shall keep an individual record for each beneficiary who obtains services from it’. http://legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/ ShowDoc/cs/S-4.2; http://legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/ShowDoc/cr/S-5,%20r.%205/

- 2.

La tenue de dossier, guide explicatif. Ordre des psychologues du Québec, January 2006, p. 3.

- 3.

The evaluation note always corresponds to a unit of measurement, but not the intervention notes that follow.

- 4.

The mission of the ʻCentre Spiritualitésanté de la Capitale-Nationale’ (CSsanté) is to ensure planning, coordination, provision and assessment of quality clinical activities, in order to respond to the spiritual and religious needs of people who are hospitalized, in residential homes or receiving care at home. It thus brings under one umbrella all the spiritual care provided by health institutions and the social services of the city of Quebec and the surrounding districts of the Capitale-Nationale. We have a team of over 40 spiritual care coordinators working at 35 sites belonging to three institutions in the health and social services network.

- 5.

Centre de pastorale de la santé et des services sociaux. Guide de rédaction de notes au dossier en pastorale de la santé, 2008.

- 6.

In Quebec, the profession was closely linked to the Catholic Church; up until 2011, most professionals received their pastoral mandate from the church.

- 7.

Following the evaluation meeting, the SCP (ISS) will record the patient’s score on a progress note sheet, if necessary.

- 8.

In our territory, this scheme is mainly used in our long-term centres, but it could be appropriate in the short-term work, particularly in geriatrics.

- 9.

At CSsanté we hold regular workshops on clinical work. A group of six or seven SCPs led by a clinical coordinator gets together to exchange experiences and know-how, with the aim of improving practices.

- 10.

Research entitled ʻDéveloppement d’un outil pour l’évaluation en soins spirituels’ (Developing a spiritual care assessment tool) by Bruno Bélanger, Mario Bélanger, Chantal Bergeron, Line Beauregard and Guy Jobin, 2016–2017. In all, 43 SCPs from nine institutions in the Quebec health network participated in the project.

- 11.

These four markers may be expressed by the patient in terms of spiritual suffering or of spiritual well-being.

- 12.

STIV: Sens, Transcendance, Identité et Valeurs

- 13.

ST-VIAR: Sens, Transcendance, Valeurs, Identité, Appartenance, Rituels

- 14.

We explain in more detail what we mean by ʻtranscendent experience’ in the Spiritual Vision Underlying RESS section.

- 15.

See also Rosselet and Collaud, writers who inspired CSsanté’s approach.

- 16.

The etymology of the word ʻtranscendence’ has two roots: ʻtrans’ and ʻascendere’, ʻascendere’ means ʻto rise’ and ʻtrans’ means ʻacross’ or ʻbeyond’. According to Roy (2014, 222), the words ʻtranscendence’ and ʻself-transcendence’ characterize this phenomenon as movement across and beyond human actions. [...] Transcendence is expressed through human actions and puts us in direct contact with the beyond. Roy (2014, 223) understands self-transcendence to be a situation in which human being begins to move outside of themselves when they pose questions regarding the what, why and how of what they perceive. Such questions force us to search for relationships between things and their meaning. [...] Human beings do not only ask questions about meaning but also about truth and value.

- 17.

Zundel (2005, 65) explains: ‘Heidegger asserts, with remarkable profundity, that a person’s being resides in their ability to exist. This essentially amounts to saying that man given to himself by his physical birth remains open, incomplete, unfinished. Whilst other beings, animal, vegetable and mineral are “in-sistent” – that is to say, opaque to themselves and closed to themselves – human beings are “ek-sistent”, destined to turn outwards, to choose at each moment between potential ways of being, i.e. to choose oneself, as Sartre puts it’.

- 18.

‘Spirituality involves more than a substantive content area. It is not a static, frozen set of beliefs or practices. It is instead a process of searching, a search for the sacred’ (Pargament 2007, 52).

- 19.

Rosselet (2002, 6) says in this regard: ‘It seems from experience that the “loftiest” questions are very deeply rooted in the simplest everyday life’.

- 20.

A good assessment/intervention note must respect certain quality criteria; these are set out in Appendix A.

- 21.

In some of our institutions, information of this type is already recorded in the patient’s electronic record and can be transferred directly to the SCP’s notes.

- 22.

- 23.

The transcendent experience is not easy to define objectively. It is considered in the section in which we discuss our vision of spirituality. Several works in the bibliography may provide greater explanation. See in particular Fromaget, Roy, Zundel.

- 24.

In some cases, there is no support marker: the patient’s suffering is overwhelming. Alternatively, there is no obstacle marker: the patient seems to be bathing in a state of spiritual well-being.

- 25.

Document developed by the Spiritual Care Team of the CSSS Pierre-Boucher: Julie Bolduc, ISS, coordonnatrice professionnelle, Bruno Godbout, ISS, Ivan Marcil, ISS et Johanne Philipps, ISS (nov. 2014). Note that to maximize consistency with the type of vocabulary used in our text, we have replaced the word ‘indicateur’ with ‘repère’.

- 26.

We have drawn up this guide for patients who can no longer express themselves, considering that for many of these patients, a relative or friend may be able to provide enough information to the SCP for them to be able to intervene appropriately. In other cases, the SCP can obtain the information from the patient record.

- 27.

This approach differs from the one presented before, in that the patient is no longer in a stage of developing meaning but in a stage where, in the interventions, we reflect the main axes of meaning in his or her life.

References

Brassard, Yvon. 2000. Apprendre à rédiger des notes d’observation, 3e édition, volume 1–2, Longueuil: Loze-Dion.

Bryson, Ken. 2015. Guidelines for conducting a spiritual assessment. Palliative and Supportive Care 13: 91–98.

Caenepeel, Didier. 2017. Conférence prononcée au CSsanté à Québec (Février 2017).

CPSSS. 2008. Guide de rédaction de la note au dossier, Centre de pastorale de la santé et des services sociaux, document inédit.

De Loyola, Ignace. 1991. Écrits (Collection Christus no 76). Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, Montréal: Bellarmin.

De Lubac, Henri. 1990. La lumière du Christ. Tome 1: Théologie de l’Histoire, 115–121. Paris: Desclée De Brouwer.

Dumas, Marc. 2010. La spiritualité aujourd’hui: Entre un intensif de l’humain et un intensif de la foi. Théologiques 18/2: 199–211.

Fromaget, Michel. 2007. Naître et mourir, anthropologie spirituelle et accompagnement des mourants, François-Xavier de Guibert, Paris. Document inédit.

———. 2008a. De l’esprit comme objet d’expérience/introduction à la phénoménologie de l’esprit, conférence prononcée à Québec. Document inédit.

———. 2008b. Conception spirituelle de l’homme et accompagnement des mourants, conférence prononcée à Québec. Document inédit.

———. 2009. Anthropologie et soins de santé, les trois dimensions de la personne humaine. Spiritualitésanté 2009: 12–22.

Kellen, Jacqueline. 2015. Le bréviaire du Colimaçon. Paris: Desclée et de Brouwer.

Marin, Claire. 2013. La maladie/entre crise et critique. Spiritualitésanté 6 (3): 14–16.

Pargament, Kenneth I. 2007. Spiritually integrated psychotherapy/understanding and addressing the sacred. New York/London: The Guilford Press.

Rosselet, François. 2002. Prise en charge spirituelle des patients: la neutralité n’existe pas. Revue Médicale de la Suisse Romande 122: 175–178.

Roy, Louis. 2014. L’expérience de transcendance. Phénoménologie et analyse critique. Mediaspaul: Montréal.

Rumbold, Bruce. 2013. Spiritual assessment and health care chaplaincy. Christian Bioethics 19 (3): 251–269.

Ugeux, Bernard. 2001. Retrouver la source intérieure. Ivry-sur-Seine: De l’Atelier.

Waaijman, Kees. 2006a. What is spirituality? Acta Theologica Supplementum 8: 1–18.

———. 2006b. Conformity in christ. Acta Theologoica Supplementum 8: 41–53.

Zundel, Maurice. 2005. Je est un autre. Paris: Éditions Le Sarment. (publication originale 1971).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendices

1.1 Appendix A: Features of a Note to File

Both an assessment/intervention note and a development note must have certain features in order to perform the functions that are intended (Brassard 2000; CPSSS 2008).

1.1.1 Clarity

Clarity in a note can be achieved in a number of ways: it must be precise, concise, chronological and readable. In other words, the note to file tells the key elements of a spiritual care intervention in just a few words and can be quickly grasped and understood by other professionals and by the users themselves. ‘A note is precise when it contains no superfluous elements and does not allow room for interpretation. It is understood in the same way by all those who read it and does not contain any uncertainty’ (Brassard 2000, 13).

1.1.2 Readability

A note must be easily readable and free of spelling and syntax errors. These last two elements may seem unnecessary, but in fact they promote clear communication and reflect the professional quality of the services provided. In addition, they reduce the risk of a note being misinterpreted. In other words, a note which is clear is one that constitutes a coherent and easily understandable whole.

1.1.3 Reliability

It is assumed that what is written in the note to file is true and reliable, so that any user consulting their file would recognize themselves in what was written and would not be hurt by it. Anything recorded is truthful, that is, it reflects what has been said and done in reality.

1.1.4 Relevance

A relevant note is one which reports on the content of the interview and what was observed, heard and seen with the user. It describes what they said, their behaviour and their reactions in a specific context or situation. If, occasionally, the note refers to facts about the surroundings or reactions from other people, it should only do so if these shed light on the user’s own experience and reactions.

As we will see later on, the assessment note may mention actions taken by the SCP. The note also describes the effect of the intervention on the user: how do they react to it, and what effect does it have on them?

1.1.5 Objectivity

An objective note allows us to understand unequivocally the SCP’s professional opinion on what the patient expresses and their analysis and objectives.

1.1.6 Writing Time

Finally, the note to file should be written as quickly as possible; the information should be recorded when it is fresh in the mind and the memory is still reliable. If, exceptionally, a note to file cannot be written on the same day as the meeting with the user, the SCP must write the note later on. In this case, the SCP records the date and time at which the note is written and writes in the past tense, specifying in the note the date and time of the meeting with the user .

Source: Centre Spiritualitésanté de la Capitale-Nationale’ (CSsanté). Reproduced with permission. Copyright © 2019 CSsanté. All rights reserved

1.2 Appendix B: Identification of a Support Marker/Obstacle Marker

Identification of a support marker/obstacle marker (beliefs/practices, hopes, relationships, values/commitments) | ||

|---|---|---|

Support marker | ||

Significance (ability to understand) Does the identified marker help the patient understand what is happening to him/her? | Direction (ability to project oneself) Does the identified marker help the patient to envisage the future? | Sensations (felt positive) Does the identified marker bring the patient good sensations or help him/her to feel something good? |

Obstacle marker | ||

Significance (inability to understand) Does the identified marker generate questions or misunderstandings? | Direction (inability to project oneself) Does the identified marker generate fears or questions about what is coming? | Sensations (felt negative) Does the identified marker generate negative sensations or negative feelings? |

Commentary

In Germany and Switzerland, pastoral care in hospitals is mostly a matter for the church. The Quebec model of recording spiritual care has a different cultural and organizational background and can therefore seem strange to Swiss and German chaplains. First of all, whenever a professional intervention takes place, it has to be recorded In Quebec, admissible interventions are assigned a value in “units of measurement” and care providers are required to compile a record of all such interventions. This means: For each unit of measurement reported, there must be a note on file. Bruno Bélanger’s report strikingly illustrates contextual embeddedness of the model, which has been in development since 2002. It is important to know the whole story, which Bélanger and others tell. There is a debate in Switzerland about the lessons to be learned from the Quebec model. Maybe the Canadian experience will help assuage some fears; maybe it will fuel new fears.

What Bélanger et al. call a paradigm change shows up in the nomenclature among other places. The professionals formerly known as chaplains have, since 2011, been called “spiritual care providers,” and they are no longer mandated by their church. The shift from the pastoral role of an emissary of the church to a clinical embeddedness within the organization weakens the religious profile of the profession, but strengthens the position of the profession. The essential question is now how a note should be made. It is no longer questioned whether spiritual care should be charted. The question of how to make a note becomes essential. There is mention of comprehensible language as well as a rationale for the intervention taken, which has to appear reasonable to members of the other professions involved in the treatment. The debate is all about implementing and evaluating a suitable tool that serves others, but also takes into account the needs of one’s own profession.

In this context two characteristics of the Quebec-model are exciting. What are called “Markers for Spiritual Care Assessment” (RESS) in Quebec are given in order to structure and format the charting. The common goal of the “treatment” provides the structure, while special attention to the spiritual realm demands a corresponding terminology Bélanger et al. make it clear that they think of this as essential. A degree of uniformity increases intelligibility and facilitates the provision of spiritual care. The diagram in the first conceptual part of the manual provides information about the anthropology which guides the work of spiritual care providers. In my opinion, the core of the anthropology is most inspiring and theologically coherent. Bélanger et al. call the center a “transcendent experience.” In the chapter, the origin of this term is only briefly discussed. However, there are indications enough of the originality of the diagram. Thus, the mention of Meister Eckhart suggests traces of the “divine spark” and the “fruit of the spirit” marks an interest in biblico-theological reflection upon the spiritual moment in a biblico-theological fashion. This is remarkable and rather unusual. When talking about spirituality in the context of spiritual care, we usually move in a theology-free zone. What “sense” and “well-being” mean is left open from an ideological point of view. They can be specified in different ways. Of course, these dimensions also occur in the present diagram. But meaning is, characteristically, a “shell” around the spiritual core. The center is therefore an experience “which goes beyond normal life.” To call it “transcendent” is to assert its unavailability.

Bélanger et al. consider this transcendent innermost core as a potential: it can be intuited, but it can’t be manipulated; it eludes treatment and calls for expert guidance. What is the charm of this model? It allows the proprium of the work of the spiritual care provider to be communicated in an adequate way. Through the courageous centering of transcendent experience, it can also be made plausible that the spiritual process triggered by the crisis of a disease can lead to personal transformation. What spiritual care providers can do differs from what a doctor, a nurse, or a therapist can do. Spiritual care providers accompany patients through change, while testifying to that change and searching for a language to be found “in the nook and crannies of everyday life.” The Note-Writing-Guide is geared to this central task! This is very impressive!

Nevertheless, I think the question can be raised whether there are theological pathways to determining the transcendence Christologically. It is certainly no coincidence that spiritual-theological terminology is based on pneumatology. But this does not mean that Christological explication would be superfluous. I think that theological self-reflection on the part of the Christian spiritual care provider could deepen and differentiate the transcendent experience.

To summarize, for me the Quebec Model is highly persuasive. Despite its different background to Swiss context, it is an attractive and, in many ways, stimulating example of a charting culture in a clinical setting. The spiritual care provider participates in a joint recording project. I like the idea of a container which contains all the relevant information necessary to give the patient the best treatment possible. However, the European reader will be struck by the fact that there is not even a rudimentary debate about the potential risks posed by the contribution of documentation by spiritual care providers. Among other things, this has to do with professional self-image. Spiritual care providers conceive themselves as part of a team that has a common goal for which the user’s social and health care record is an essential tool: “One of its key functions is to promote communication between all those involved in the patient’s treatment.” Bélanger et al. make it very clear that they support a disciplined charting culture and that they take the involvement of the spiritual care providers for granted. In my view, it is interesting that in Quebec the change of system, which was started in 2002 with a directive from the ministry, has been implemented in such a highly constructive way. What was more or less a forced change has been taken as an opportunity to reposition the spiritual care provider within the health system.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bélanger, B., Beauregard, L., Bélanger, M., Bergeron, C. (2020). The Quebec Model of Recording Spiritual Care: Concepts and Guidelines. In: Peng-Keller, S., Neuhold, D. (eds) Charting Spiritual Care. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47070-8_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47070-8_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-47069-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-47070-8

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)