Abstract

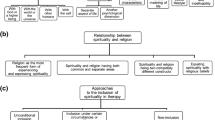

Part II of this book illustrates the importance of cultural values in enriching the philosophical theory underpinning values-based mental health care. Building on the origins of values-based practice in ordinary language philosophy (see Chap. 1), the contributions of a culturally enriched theory to practice are illustrated by the roles, respectively, of aesthetics (Chap. 7), phenomenology (Chaps. 8 and 9), African philosophy (Chaps. 10 and 11) and feminist philosophy (Chap. 12). Chapters 13 and 14 in contrast illustrate how practice may also inform theory. They explore through a series of narrative examples, the boundary of the concept of mental disorder as represented by the contested relationship between spiritual/religious experiences and psychopathology. The selection of topics presented in this Part is representative, though far from exhaustive, of the scope for two-way engagement between culturally enriched philosophical theory and mental health practice.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Why theory? Or as a contributor to one of our writing workshops put it, why did we put not just theory but philosophical theory first in the book? This is a good question to which we have no unassailable answer. Certainly, it was not in hopes of the popular vote—in an age of “18-character ‘tweets’” a book approaching 180,000 words could hardly be accused of courting popularity. Neither was it out of any assumed priority of theory over practice. We were not buying into the traditional idea that philosophy is, as it has sometimes been said to be, ‘the queen of the sciences’, a necessary ground-clearing preliminary for the heavy lifting of empirical science.

1 Widening the Theory Base

True, the practice of values-based practice (including its principle elements and their enactment through training in clinical care) was derived originally as we described in Chap. 1,Footnote 1 from work in ordinary language philosophy. True, also, our book was motivated, in part, though importantly, by recognition that the further development of values-based practice required a widening of its philosophical base to encompass philosophies that are less individual focused than was ordinary language philosophy. That is why our book is about cultural values. It is also why the philosophies included in this first part of the book are predominantly from the traditions of Continental Europe and Africa. Elsewhere in the book, we extend these sources still further to include, for example, those of South East Asia and Brazil. All these philosophies, as their respective chapters illustrate, reflect the relational more than individual character of human values.

1.1 Building on Two-Way Partnerships

But all that being said, perhaps the real reason that we put theory first was to emphasise the fact that values-based practice, and the wider movement in philosophy and mental health from which it is derived,Footnote 2 were from the very start conceived as building on partnerships between theory and practice. The partnerships in question, moreover, were conceived, again from the very start, essentially as two-way partnerships . That is to say, whilst in such partnerships theory does indeed inform practice, so practice also informs theory. That is why the interdisciplinary field from which values-based practice was derived is a ‘Philosophy and … discipline’ not a ‘Philosophy of … discipline’.

The conjunction ‘and’ says it all. There are, nowadays, in today’s pragmatically justified academic world, many philosophies of this or of that practical area (of psychology, of physics, of politics and so forth). The idea perhaps is that philosophy is somehow justified by its contributions to the practical disciplines in question. However, the field from which values-based practice was derived is and has been from the start very definitely a ‘philosophy and … discipline’, a discipline based on a two-way partnership between philosophy in all its richness and the no less-rich disciplines of mental health practice.Footnote 3

2 Theory as a Resource for Practice

As indicated in the Table 6.1, the two-way partnership between theory and practice is explored in this Part mainly from the side of theory, drawing in particular on sources in the philosophy of values.

Thus, in Chap. 7, Oliver Scheibenbogen and Michael Musalek draw on cultural history and aesthetics in their description of a novel application of the ‘will to beauty’ (experienced by most human beings) as a therapeutic agent in the treatment of addictive disorders . The next two chapters together illustrate the power of phenomenology to draw out and make explicit the otherwise taken for granted (and hence largely invisible) cultural values that are important in shaping psychopathology , respectively, in eating disorders (Giovanni Stanghellini and Melena Mancini, Chap. 8), and in psychosis secondary to trauma (Michèle Gennart, Chap. 9).

Other philosophies may be illuminating in quite different ways. African philosophy is represented here first (in chap. 10 by Camillia Kong’s exploration of Critical Sankofaism for working with conflicting values. Temitope Ademosu and her colleagues (chap. 11) then explore the importance of story telling within the African tradition. There are further examples of the role of African philosophy later in the book.

Finally in this section, Janelle Kwee and Hilary McBride (Chap. 12), drawing on a (disguised) narrative of anorexia from their own practice, show how feminist theory not only illuminates the cultural values driving psychopathology but may directly guide forms of therapy motivated by the aim of restoring the agency of the person concerned.

3 Practice as a Resource for Theory

With the remaining two chapters in this Part (Chaps. 13 and 14) we turn from the role of theory in illuminating practice to the other side of the two-way partnership, the role of practice in illuminating theory. Both chapters explore the boundary between mental disorder and spiritual or religious experience . The richly nuanced and complex nature of the boundary as illuminated by their respective narrative materials illustrates the importance of embedding philosophical analysis (in this case of the concept of mental disorder) in the details of the stories of real people rather than relying (as philosophers still all too often rely) on generalisations based on a restricted range of ‘canonical’ cases.

The conceptual issues arising in mental health—including radically different views on how the very concept of mental disorder should be understood—are of course wide ranging and matters of on-going debate. We do not have space to explore these issues in detail.

One such issue, however, to which the grounding of these two chapters in the experiences of real people, makes a distinctive contribution, is the role of values in defining mental health issues . There is much to be said even on this restricted aspect of the debate about mental disorder: it is a case in point after all of the is-ought debate of general ethical theory [2]. As to the boundary problem, furthermore, one view might be that, to the extent that the boundary involves values, it is really rather well defined: pathology, this view might suggest, is characteristically a negative and disempowering experience, whilst spiritual and religious experiences are characteristically positive and empowering. Yet as the stories in these two chapters, respectively, about suicidal behaviour (Chap. 13) and psychotic experiences (Chap. 14), make clear, the boundary of pathology can prove surprisingly difficult to draw along these lines, with both positive and negative aspects sitting side-by-side in the complexity of particular cases.

Again, the conceptual issues raised by these two chapters are deep indeed. Their bottom line, though, consistently with the bottom line of the three exemplar chapters in Part I, is that in whatever way the wider conceptual boundary is drawn, cultural and other values play an irreducible role in shaping the presentation and management of mental health issues.

4 Other Areas of Philosophy

Although we have focussed in this Part on philosophy of values , there are similarly rich two-way connections to be found in many other areas of philosophy—philosophy of mind, for example, and of science, are self-evidently cases in point. With our aim of extending values-based practice to cultural values, it was natural that philosophies of value would be our first port of call. But even with this limited aim in mind, we could have included a number of other sources. Within analytic philosophy , for example, the philosopher Anna Bergqvist, who leads the Theory Network in the Collaborating Centre for Values-based Practice in Oxford, is working on evaluative perception [3]; and the lead for the Centre in North America, Nancy Potter, has an on-going research programme on the nature of ‘uptake’ and its links with such key areas of mental health practice as co-production and recovery [4].

Again, there are other philosophies not standardly part of moral theory with potential for two-way exchange with mental health practice: political philosophy, for example, and hermeneutics. We return to the potential role of political philosophy in the introduction to our concluding Part VI (see Chap. 43). Hermeneutics has a proven track record in application to mental health [5], with, as Camillia Kong notes (Chap. 10 conclusions), intriguing links to the Critical Sankofaism of African philosophy . Other examples are provided by the philosophy of mind . The nature of personal identity, for example, is a key topic in this area of philosophy directly relevant to understanding the relationship between individual and cultural values [6].

Therefore, the scope is wide indeed. But for now, and for this book, we hope our selection is sufficient to indicate the potential for two-way exchange that exists between philosophical theory and mental health practice.

5 An Endorsement from Practice

In the early days of the Oxford Collaborating Centre for Values-based Practice , we received endorsement for this partnership model of the relationship between theory and practice from an unexpected but at the same time very welcome source. Over this period, the Centre was generously supported by an Advisory Board made up of senior members of many of the key organisations responsible for practical implementation of health care in the UK through the NHS (National Health Service). One might be forgiven for expecting that such a practically focused group would resist the Centre’s proposed inclusion of a strong commitment to theory. But quite to the contrary, the Advisory Board welcomed it. Theory, they said, was our one defence against the everyday pressures of ‘dumbing down’ to which so many initiatives in the NHS had fallen prey. Evidence-based medicine (to which we return in Part IV) was a case in point.Footnote 4 Theory is in itself no guarantee that values-based practice will not suffer a similar fate. But absent theory, the Advisory Board said, and a similar fate is more or less guaranteed.

6 Conclusions

The contributions to this Part illustrated some of the many ways in which a culturally enriched form of values-based practice may draw to good effect on an enlarged theoretical base. Building on its origins in the ordinary language tradition of analytic philosophy, contributions to the Part explore the roles in values-based practice, respectively, of aesthetics, of phenomenology, of African philosophy, and of feminist philosophy. Elsewhere in the book as we have indicated, these resources are extended still further, to those of Buddhism and of Brazilian philosophy. We have noted that our selection is far from exhaustive even of the resources of analytic philosophy. We have emphasised the two-way nature of the partnership between theory and practice, with practice informing theory just as theory informs practice. The role of practice in informing theory is illustrated in the last two chapters in this Part by an exploration of the conceptual boundary between psychopathology and religious experience.

We concluded with an endorsement of the role of theory from the very practical perspective of the Advisory Board for the Collaborating Centre for Values-based Practice in Oxford. The richness of the contributions to this Part of the book, we believe, amply justify our Advisory Board’s endorsement of the importance of theory as a partner to practice in the delivery of mental health care. The richness of the contributions to the book as a whole amply justifies our claim that the relationship between theory and practice is one of two-way partnership. Theory first, then, we conclude, but certainly not last.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

See Guide to Further Information below for examples and sources.

- 4.

Evidence-based medicine is nowadays widely regarded as being just about best evidence. Yet over 20 years ago, one of the founders of evidence-based medicine, David Sackett, defined it as being about combining best research evidence with clinical experience and patients’ values [7, p. 1].

References

Fulford KWM, Morris KJ, Sadler JZ, Stanghellini G, editors. Nature and narrative: an introduction to the new philosophy of psychiatry. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003.

Fulford KWM. Moral theory and medical practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1989, reprinted 1995 and 1999.

Bergqvist A, Cowan R. Evaluative perception. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2018.

Potter NN. In the spirit of giving uptake. Philos Psychiatr Psychol. 2003;10(1):33–5.

Widdershoven G, Widdershoven-Heerding I. Understanding dementia: a hermeneutic perspective. Chapter 6. In: Fulford KWM, Morris KJ, Sadler JZ, Stanghellini G, editors. Nature and narrative: an introduction to the new philosophy of psychiatry. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. p. 103–12.

Wilkes KV. Real people: personal identity without thought experiments. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1988.

Sackett DL, Straus SE, Scott Richardson W, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

Fulford KWM, Davies M, Gipps R, Graham G, Sadler J, Stanghellini G, Thornton T. The Oxford handbook of philosophy and psychiatry. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013.

Fulford KWM, Thornton T, Graham G. The Oxford textbook of philosophy and psychiatry. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Additional information

Authors

The editors with input from the contributors to Part II.

Guide to Further Information

Guide to Further Information

The Oxford book series, International Perspectives in Philosophy and Psychiatry (IPPP) includes many volumes illustrating both the contributions of theory to practice and the contributions of practice to theory (for comprehensive selections of materials, see for example, [8, 9]).

These and many other resources are indicated in the website of The Collaborating Centre for Values-based Practice in Oxford (valuesbasedpractice.org—see especially the section ‘More about VBP’) and that of The International Network for Philosophy and Psychiatry (INPPonline.com—this includes free-to-download materials from The Oxford Textbook of Philosophy and Psychiatry, [9]).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Fulford, B. (2021). Theory First: An Introduction to Part II, Theory. In: Stoyanov, D., Fulford, B., Stanghellini, G., Van Staden, W., Wong, M.T. (eds) International Perspectives in Values-Based Mental Health Practice. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47852-0_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47852-0_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-47851-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-47852-0

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)