Abstract

Throughout the industrialised world, societies are ageing. These demographic changes have created a political and societal focus on an extended working life. Unfortunately, there is a lack of systematic knowledge about how such changes can be successfully implemented within organisations. In this chapter, we discuss this lacuna and specifically focus on organisational capability. We highlight workplace conditions and practices that may inhibit or promote the retention of workers beyond the previous norm for retirement.

The novelty of an organisational capability approach is that it highlights workplace conditions that enable older people to use their abilities to perform acts of value and to achieve a better quality of life and greater participation in society. Workplace resources, capabilities and functions form a dynamic pattern. Factors that influence the work abilities of older workers are related in complex interactions and not merely in the format of simple cause and effect.

When looking at retirement from the perspective of older workers, we have focused on aspects such as the individual’s ability to control the retirement process. Central to Sen’s idea is that individuals have different conversion factors, which means that, even though two individuals may have access to the same resources, they do not necessarily have the capability to enjoy the same functions. For example, the probability that an older person will remain employed will partially depend on his or her health, human capital and type of job. But two seemingly similar individuals can nevertheless have very different chances of remaining employed because their employer has implemented very different age management policies, or simply because they have different attitudes towards older workers. Since organisational capability makes it possible to focus on the interaction between the individual’s resources and preferences and the opportunity structure existing at the workplace (meso level) and embodied in the retirement system (macro level), much of the discussion and many of the policies and practices concerning older people can be related to the concept of capabilities.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

16.1 Introduction

This chapter highlights the meso level in the capability approach by focusing on how organisations address problems and opportunities associated with an ageing workforce by applying various age-management measures. In order to characterise the ability of organisations to promote the delayed retirement of older workers, we turn to the concept of organisational capability.

The increasing proportion of older people in Sweden has created the need for an extended working life and delayed retirement. Three reasons are often cited for the need to delay retirement: (a) to ensure a sustainable pension system, (b) to ensure the availability of sufficient labour and the effective use of the human capital possessed by older workers and (c) to contribute to the welfare of older people. Therefore, in 2013, the Swedish Pension Age Commission of Inquiry (SOU, 2013:25) proposed a set of changes to the pension system framework aimed at increasing the incentives for older people to work longer. However, to meet and participate in these changes at the policy and individual levels, changes in organisational practices are also required. Unfortunately, there is a lack of systematic knowledge about how such changes can be successfully implemented within organisations. In this chapter, we discuss this lacuna and specifically focus on organisational capability. We highlight workplace conditions and practices that may inhibit or promote the retention of workers beyond the previous norm for retirement.

The novelty of an organisational capability approach is that it highlights workplace conditions that enable older people to use their abilities to perform acts of value and to achieve a better quality of life and greater participation in society. The specific goal of this chapter is to contribute to knowledge about organisational capability and our understanding of the meso level in the capability approach.

The workplace and the actions taken by employers have received much less attention than research on demographics, pension system financing or individual circumstances (SOU, 2013:25). Workplace resources, capabilities and functions form a dynamic pattern. Factors that influence the work abilities of older workers are related in complex interactions and not merely in the format of simple cause and effect (Ilmarinen & Ilmarinen, 2015; McDermott et al., 2010; Henkens et al., 2009; Hasselhorn & Freude, 2007; Brooke & Taylor, 2005; Henkens, 2005; Ilmarinen, 2006a, b). As several research teams have discovered, the organisation of workplaces is of central importance in addressing physical strains, psychosocial work environment, work-group norms, the division of labour, leadership and management support for older people’s abilities and their preference to continue working (Furunes et al., 2011; McDermott et al., 2010; Brooke & Taylor, 2005).

16.2 Organisational Research

Organisational research addresses a wide variety of societal challenges facing today’s organisations, including sustainability issues, questions pertaining to demographic challenges, the integration of a diverse workforce, diversity, equality, business case approaches, work environment and the ongoing institutional efforts to negotiate the relationship between old regimes and new beliefs. Ageing represents a global societal challenge and, in order to achieve health equality and maintain good health in the workplace and during later life, we need to focus on the potential to increase capabilities within organisations, at the societal level and at the individual level. Coordinated scientific efforts are needed to facilitate sustainable ageing within organisations and across societies. The ultimate goal is to ensure that people can experience continued overall functioning and participation in the workplace and in societal life continuing into later life.

In order to promote the organisational conditions for older workers to remain in the workforce, investments in age management practices are starting to be made (Midtsundstad, 2011). The complexity and collective practices of age management within organisations is immense; they involve the physical work environment, accommodating changes in regulations, organisational and technical changes, securing competences, creating a productive work environment for workers who are devoted to their work and, also importantly, maintaining an economically efficient organisation (Furunes et al., 2011; McDermott et al., 2010; Brooke & Taylor, 2005). At the same time, actions at the organisational level have to accommodate both macro conditions, for example changes in the retirement system, and the actual composition of the workforce; that is, individual circumstance among workers, and collective perceptions of retirement prevailing among workers. With increasing life expectancy, it has become more and more important to understand the processes which are being implemented to postpone retirement age. It is against this background that the proposed study aims to develop knowledge about what organisations already do and what more they could do in relation to older workers regarding conditions that promote and/or inhibit delayed retirement.

16.3 Applying a Capability Approach Within Organisation Studies

According to Sen (e.g., 2009), capability is the ability to perform actions in order to reach goals that the individual has reason to value. Central to Sen’s idea is the notion that individuals have different conversion factors, which means that even where two individuals have access to the same resources, they do not necessarily have equal capabilities to enjoy the same functions. Because the focus of the capability approach is on the interaction between the individual’s resources and preferences (micro) and the opportunity structure that exists in the workplace (meso), and is embodied in the retirement system (macro), we propose that the policies, practices and discussions concerning older people can preferably be related to the concept of organisational capability.

What employers do and communicate in relation to older workers is, of course, one significant aspect, but so are the prevailing norms in the workforce at large: the status of older workers and prevailing discourses and expectations about retirement (LaLiberte & Molke, 2009; Trethewey, 2001; Sargent et al., 2013). Organisations may hesitate to extend the tenure of older workers because measures that benefit and promote one age group over others in organisations are likely to have both positive and negative implications. Promoting later retirement may also limit jobs for new and younger workers to a certain extent, or delay their promotions. There may also be negative effects on team dynamics, if delayed retirement leads to a greater spread of age and experience; the so-called ‘interrelationships between age groups’ in workplaces are not always easy (Brooke & Taylor, 2005). Furthermore, if efficiency is the main driver for the implementation of organisational changes, investments are only likely to be made if they are calculated to provide the organisation with economic benefits.

In terms of economic benefits, in the human resource management literature labour economists have advocated that older workers should not be the recipients of human capital investment. This view, based on neoclassical human capital theory, has been challenged. For example, Simpson, Greller and Stroh’s (2002) review distinguishes between (a) the labour economics model, and (b) the life-span career development model for human capital investment. In the labour economics model, the cost-benefit considerations are based on a comparison of the discounted net returns from education and training over the remaining years of employment before pension age. There are at least two rationales for not investing in the human capital of older workers: They are too valuable in their present job to participate in training activities, and they have too few years of work remaining to benefit the organisation.

According to advocates of the life-span development model, the payback period of training activities is generally short for any age group – perhaps of the order of 3–5 years – which tends to level out age-group differences. Moreover, older people are becoming more interested in investing in their own human capital, because they often plan to continue working up to and even beyond the official pension age (Simpson et al., 2002). So, although there is some debate on the matter, investments by organisations to keep their older workers trained and to support their continued career development can be seen as rational from a business perspective.

Irrespective of these debates, some organisations have made efforts to keep older workers longer. The term ‘age management’ has been used to describe organisational activities aimed at promoting a longer working life and/or balancing the interests and needs of varying age groups within an organisation (see e.g. Ilmarinen & Ilmarinen, 2015; Furunes et al., 2011; Midtsundstad, 2011; McDermott et al., 2010; Brooke & Taylor, 2005). Ilmarinen (2006a: 120) defines age management as ‘taking the employee’s age, and age-related factors, into account in daily work management, work planning and work organization; thus everyone – regardless of age – can achieve personal and organizational targets healthily and safely’. This way of conceiving age management places demands on both the organisation’s management and workplace practices. Brooke and Taylor (2005: 418) relate age-management practices to human resource management and the interrelationships between age groups within organisations.

We propose that the management of an ageing workforce requires awareness of the realities of the interrelationships between workers of different ages, including both the intended and unintended consequences. Yet the specific content of what, in practice, should be termed ‘age management’ is likely to vary across contexts and organisations. As an example, in this chapter we will describe the process of creating, implementing and developing age-management practices and support through a study using the action-research approach aiming to explore organisational capability by focusing on the characteristics of age management and organisational capability, as well as the mechanisms facilitating or hindering the work ability of an ageing workforce delaying the age of retirement.

16.4 Studying Organisational Capability

This intervention and case study began with the implementation of a research consortium – a group of practitioners from eight large organisations (three private companies and five public organisations) who met and continue to meet to oversee collaborations between companies and organisations that are working with issues of postponed retirement. The aim of involving a research consortium in the study design was to enable knowledge creation by including both the practitioners and the researchers’ perspectives. Accordingly, the idea of the consortium was to create a basis for sharing experiences of age management among organisations and between organisations and researchers. The consortium also had the purpose of comparing and mirroring the experiences of age management with invited researchers and practitioners from other countries.

The research consortium also formed the basis for the data collection, which has been conducted through case studies in organisational-capability research. The aim of the case-study approach has been to document and analyse age management practices as they develop. One public-sector and one private-sector organisation were selected as the primary cases for this study. The organisations both had human-resource (HR)-initiated policies and programmes that included older workers, such as mentoring and competence laboratories for knowledge sharing. The data collection involved all the relevant actors at both workplaces, including top managers, line managers, HR specialists and trade union representatives, all of whom, in different capacities, had formal responsibilities for age management. Other older and younger workers were also interviewed.

16.5 Observations of Workplace Practices: Results and Reflections

The focus on organisational capability has enabled us to observe, for example, that there are internal driving forces at the workplace level to find solutions to prolonged working life – solutions connected to labour shortages or high staff turnover and increased work-related ill health. The employers translate this situation as a need to maintain skill and knowledge retention. The employers want to keep their human capital, but also to be an attractive employer for recruiting purposes. Keeping older workers is seen as an alternative to recruiting only young people. Furthermore, in accordance with previous research (McMullin & Marshall, 2001; Snape & Redman, 2003), we found that the retaining and recruiting of older workers may be hindered by age discriminatory practices that may be based on an ageist ideology of negative stereotypes, beliefs or attitudes.

An overall observation is that age management in workplaces is often related to questions about the need for skills and a lack of labour and human capital (Wikström et al., 2018). Employers translate this situation as a need to retain competence, which is often referred to as knowledge retention or retention of know-how. However, the retention of human capital and knowledge is prevented when the focus is solely on the skills of older workers and on a view of knowledge as a ‘package’ (the commodification and technical packaging of knowledge which, like software, can be downloaded from a human into a computer or traded between people). Common knowledge retention methods are often unrelated to strategies based on a consideration of the silent dimension of knowledge or knowing in practice and its impact on knowledge management within an organisation. Retaining competence and know-how seems to be a constantly ongoing iterative process between older and younger workers in working life. Maintaining competence requires continuous interaction in the joint resolution of tasks between actors, where silent knowledge and know-how are important and central to the survival of the organisation and as part of its ‘business case’.

Accordingly, our results highlight that the managerial response to delayed retirement and extended working life is often interpreted from a business-case perspective. The societal level meta-narrative, regarding the need to delay retirement due to demographic changes, is translated and comes into conflict with organisational narratives of efficiency, where age is seen as a predictor of declining efficiency. A business-case approach to age management addresses the employer’s perspective and relates to the employer’s complex calculations in trying to enable an extended working life for workers. Such managers engage in strategic HR planning with available human capital, as they try to retain organisational competence, or even a unique competence, in the form of productive workers. Our observations also reveal more multifaceted managerial responses, in which the business case is expanded. There seems to be a growing trend towards manoeuvring the mainstream discourse and practice on a business-case rationale towards a more value-driven logic, i.e. ethical values of equal opportunities for older workers as well as the societal values of sharing responsibilities for the welfare system by extending working life. By focusing on prolonged working life and delayed retirement from a capability approach, we were able to identify and problematise different attitudes and reactions to the societal norm on delayed retirement.

Another observation is that HR routines tend to prevent a prolonged working life, despite political efforts to increase the retirement age (Liff & Wikström, forthcoming). Our results show that three HR routines are central to the prevention of prolonged working life: performance reviews, salary discussions and internal recruitment. These routines seem rational and appropriate for an organisation’s managers, since the requirements from a work and efficiency perspective must have priority over workers’ needs. In addition, it may be considered economically rational to prioritise salary requirements for younger workers compared to older workers, as well as to stop further training for older workers. In general, it thus seems reasonable for managers to make decisions based on objective criteria such as age. Nevertheless, our results indicate that these HR routines need to be adapted if they are to support an extended working life.

Accordingly, internal organisational institutions (e.g. taken-for-granted norms and ways of thinking), which are embedded in HR routines, seem to either facilitate or hinder extended working life, creating a need for change in these institutions. HR routines take time to change, but the capability approach enables us to highlight networks of endogenous institutions and mechanisms embedded in the routines that either promote or inhibit prolonged working life. This complex interaction between different routines is considered ‘institutional’ because it serves to maintain existing routines or establish new routines, policies and observable material effects (e.g., prolonged working life or retirement age changes) within a specific field (the workplace). Our observations demonstrate that path-dependence can unearth the existence of strong retirement-age norms within an organisation. Managers’ negative attitudes towards older workers can reinforce an early exit culture that is difficult to change. This hampers the organisational capability to delay retirement. The acknowledgement of existing age norms is a crucial first step in changing them.

Furthermore, from a life-course perspective, ageing occurs in a context that results in unique experiences. These experiences, in turn, affect people’s attitudes, values and accumulated resources over time, which can be seen as positive (accumulated advantages) or negative (accumulated disadvantages). In order to change the path-dependence structure, the workplace could work with a procedural life-course perspective, i.e. ageing is seen as a process that differs between individuals. Organisations and managers thus need to be able to adapt routines and relationships in relation to this transformation – which requires a combination of a life-course perspective and an organisational analysis, such as an ongoing process.

Two different logics also appear to be of great importance for workers’ retirement decisions: the logic of consequences and the logic of appropriateness. The logic of consequences, for example, describes the financial or social consequences of retirement and it has been the logic of consequences that has been given the greatest scope in research to explain individuals’ retirement decisions. The results reveal that the logic of appropriateness – the logic that describes at what age it is considered appropriate to retire – has at least as much importance as the logic of consequences for the retirement decision. This may mean that employers need to work more with values and norms in relation to what is considered to be appropriate age to retire if they intend to influence workers’ retirement decisions with the ambition to delay retirement.

16.6 Discussion

In order to determine why older workers choose to retire or to continue working beyond the general retirement age, we need to understand both the constraints and the possibilities, i.e., the opportunity structure, to which the individual is exposed before decisions about retirement are made. The opportunity structure is related to three different levels: macro, meso and micro. In this context, the macro level refers to laws and regulations that impact upon pensions, social security and the labour market, factors that at any given time will influence both what an individual can do and what they prefer to do. Macro-level changes are often guided by the explicit goal of changing incentives, i.e., making it more profitable to work longer, or constraining available exit options, e.g., changes to early retirement and disability benefit programmes.

The focus on organisational capability contributes to our understanding of the dynamic interactions that occur at the meso level, and we conclude that the configurations in which daily life is embedded, for example, family situation, social networks and the workplace. The way in which workplaces are organised when it comes to physical and psychosocial work environment, the organisation of work tasks and, not least, the employers’ motives and interests are of central importance for older people’s ability and desire to continue working. At the individual level, retirement decisions are dependent on, among other things, individual health, job satisfaction, skills and human capital, as well as retirement preferences.

When looking at retirement from the older worker’s perspective, we have for example focused on the individual’s capability to control the retirement process. For example, the probability that an older person will remain employed will depend partly on his or her health and human capital, and the type of job. But two seemingly similar individuals can nevertheless have very different opportunities to remain employed because their employer has implemented very different age management policies, or simply because they have different attitudes towards older workers. Since organisational capability makes it possible to focus on the interaction between the individual’s resources and preferences, and the opportunity structure existing at the workplace (meso) and embodied in the retirement system (macro), much of the discussion and many of the policies and practices concerning older people can be related to the concept of capabilities.

Furthermore, the societal narratives explaining the need to address early work-life exits from the labour market have little impact on the ways in which organisations articulate their internal policies with respect to retirement issues. The managerial response to delayed retirement is related primarily to a business-case perspective, to strategic HR planning in relation to available human capital, and to the desire to retain unique competences. The absence of an ageing perspective related to operative goals when implementing HR-initiated policies and programmes, such as focusing on unique competence or mentoring, may result in a marginal or negative effect on the retirement culture and delayed retirement. Furthermore, knowledge retention is hindered by focusing solely on an explicit and commodified view of knowledge. Knowledge retention is a matter of continual interaction between actors, in which tacit knowledge and knowing are important.

Moreover, the societal policy change towards the extension of working life includes how HR strategists translate and use stories about older workers in strategic staff discussions and in their policy work (Arman et al., 2021). Employers and people with managerial responsibility see questions about age management, delayed retirement and extended working life primarily from a business-case perspective. This results in narratives at a societal level about the need to delay retirement due to demographic changes coming into conflict with organisational stories about efficiency and business case, since ageing is seen as part of a process of ‘decline’, during which workers’ efficiency and productivity steadily reduce. In a business-case strategy for age management, employers focus on complex calculations in order to answer the question of whether delayed retirement will pay off.

Age management and delayed retirement are less often discussed on the basis of a value-driven logic, which emphasises ethical values about equal opportunities for older workers and the importance of sharing responsibility for the welfare system. By focusing on narratives of age management and retirement, this study has identified and problematised the institutional work of organisational representatives that maintains the perspectives of older workers. One conclusion is that the societal narratives explaining the need to address early retirement from the labour market have little impact on how organisations formulate their internal policies on retirement issues.

In sum, both the views on knowledge and competence, and assumptions about how older people can carry out their work, are of great importance in determining the length of their working life (Kadefors et al., 2020; Wikström et al., 2018; Wikström & Liff, 2019). These notions and assumptions, in turn, are embedded in the HR routines used by operational managers in their interactions with workers. The interaction between the chief operating officer and the employee, which occurs during the application of routines, can lead to retirement decisions being almost predetermined or predestined. Therefore, the perspective of age management needs to be broadened to include the interactions between managers and workers. The importance of examining underlying factors and assumptions has been described, and such transparency can have a major impact on how long a career will last.

16.7 Conclusion

Altogether, three types of conditions seem central to organisational capability for extended working life:

-

1.

How older people’s knowledge and skills can be seen as worth preserving within an organisation, and what organisational measures are required in order to succeed (Wikström et al., 2018). Employers and managers may need to review and redefine the view of knowledge and know-how in order for both younger and older people’s knowledge and know-how to be valued within the framework of what is perceived as profitable and effective.

-

2.

The operational managers’ use of HR routines for workers’ career curves and what inherent norms are embedded in these routines that need to be influenced in order for the routines to contribute to an extended working life (Liff & Wikström, 2020a, b; Wikström & Liff, 2019). One question raised by this research review concerns the obstacles that are created for older people in working life when HR routines – such as performance reviews and educational efforts – are standardised. There may be a need for operational managers to adapt such HR routines in relation to workers’ life-course (Liff & Wikström, 2020a; Wikström & Liff, 2019; Kadefors, 2019).

-

3.

The HR function for the exercise of age management (Wikström & Liff, 2019). The HR function can play a central role in strategic management as well as enabling operational line managers to integrate age management into their organisation. This is about the HR function being able to demonstrate the way in which age management can be seen as part of a value-creating process (i.e. as part of a business case); for example, by illustrating statistics about the demographics of the organisation.

A key conclusion is that there is a need to broaden the perspective and meaning of age management. Such a broader perspective focuses on how employers and managers interact with their workers through the use of different personnel management routines. Organisational conditions for an extended working life not only include changes in the workers’ work organisation as well as their physical and mental work environment, but it is at least as important to consider how employers and managers interact with all workers, regardless of age.

We have highlighted the importance of how knowledge is defined within organisations and how one values the knowledge and know-how of both older and younger people within an organisation. It is also important to consider how operational managers interact with workers through their use of HR routines in recruitment, promotion and salary setting, which will affect older people’s opportunities for a long, sustainable and successful career (as long as they have the capacity and willingness to remain at work). How older people can contribute with their knowledge in a workplace also plays a central role for an extended working life. An interactive perspective on age management can contribute to an in-depth knowledge and understanding of organisational capacity for delayed retirement and of the dynamic interaction patterns within the workplace, as well as the importance of an extended working life. The norm for an appropriate retirement age is also an important factor in the interaction between operational managers and workers.

The definition of an upper retirement age and a fixed retirement age appears to play a central role in the norm of an appropriate retirement age. This research highlights the need to relax such norm formations within organisations in order to enable an extended working life. However, this will probably require that societal norms and institutional frameworks are changed to modify the conditions for organisational actors – such as managers and HR – and thereby create pressure to change the norms, actions and routines of these actors. This could be achieved through a variety of measures. In the same way that changes in societal norms and institutional frameworks relating to the upper retirement age could affect the norm regarding an appropriate retirement age, tax reforms relating to the elderly could have a similar effect.

The concept of organisational capability for a longer working life thus highlights a number of complex interactions. Firstly, each individual’s decision about retirement depends upon a number of composite factors, such as health, social networks, preferences and economic conditions. It has to do with the socio-economic aspects of age, and our work has highlighted the complex interplay between different factors and older workers’ approach to extended working life within four categories: ‘can and want to’, ‘can but do not want to’, ‘cannot but want to’, and ‘cannot and do not want to’ (Kadefors et al., 2020). However, in this text, we have mainly focused on the interactions between different organisational conditions and prospects that affect the possibility of an extended working life. The conditions are assumed to influence both the individual’s ‘can’ and their ‘want to’.

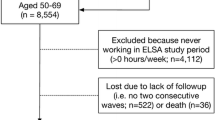

Central societal norms and institutional frameworks include norms on appropriate retirement age, laws and regulations, as well as taxes. Significant organisational conditions are views of knowledge and skills, HR routines, notions of appropriate retirement age, HR function, flexible working conditions and organisational work environment. Individual factors include health, preference, finances and flexible conditions in the workplace. This complex interaction, which is manifested in the practice of age management, can lead either to a change in patterns of action and an extended working life or to a stabilisation of patterns of action and retirement. The interaction can be illustrated with the following image (Fig. 16.1).

References

Arman, R., Kadefors, R., & Wikström, E. (2021). We do not discuss age here. A study of organizational narratives of retirement timing. (In press). Ageing & Society.

Brooke, L., & Taylor, P. (2005). Older workers and employment: Managing age relations. Ageing and Society, 25(3), 415–429.

Furunes, T., Mykletun, R. J., & Solem, P. E. (2011). Age management in the public sector in Norway: Exploring managers’ decision latitude. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(06), 1232–1247.

Hasselhorn, H., & Freude, G. (2007). Der Work Ability Index: Ein Leitfaden. Wirtschaftsverlag NW.

Henkens, K. (2005). Stereotyping older workers and retirement: The managers’ point of view. Canadian Journal on Aging, 24(4), 353–366.

Henkens, K., Van Solinge, H., & Cozijnsen, R. (2009). Let go or retain? A comparative study of the attitudes of students and managers about retirement of older workers. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39(7), 1562–1588.

Ilmarinen, J. (2006a). The ageing workforce: Challenges for occupational health. Journal of Occupational Medicine, 56(6), 362–364.

Ilmarinen, J. (2006b). Towards a longer worklife: Ageing and the quality of worklife in the European Union. The Finnish Institute of Occupational Health.

Ilmarinen, J., & Ilmarinen, V. (2015). Work ability and aging. In L. Finkelstein, D. M. Truxillo, F. Fraccaroli, & R. Frankel (Eds.), Facing the challenges of a multi-age workforce: A use-inspired approach. Routledge.

Kadefors, R. (2019). Att vilja och kunna arbeta längre. Underlagsrapport till Delegationen för senior arbetskraft rapport, 9(S 2018), 10.

Kadefors, R., Wikström, E., & Arman, R. (2020). The capability of organizations to manage delayed retirement. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 7(1), 38–51. https://doi-org.ezproxy.ub.gu.se/10.1108/JOEPP-06-2019-0047

LaLiberte Rudman, D. L., & Molke, D. (2009). Forever productive: The discursive shaping of later life workers in contemporary Canadian newspapers. Work, 32(4), 377–389.

Liff, R. & Wikström, E. (2020a). Prolonged or preserved working life? Intraorganisational institutions embedded in human resource routines, Ageing and Society, 1–19.

Liff, R., & Wikström, E. (2020b). An interactional perspective on age management for prolonged working life. Nordic Journal of Welfare Research, 5(2), 137–139.

McDermott, H. J., Kazi, A., Munir, F., & Haslam, C. (2010). Developing occupational health services for active age management. Occupational Medicine, 60(3), 193–204.

McMullin, J. A., & Marshall, V. W. (2001). Ageism, age relations, and garment industry work in Montreal. The Gerontologist, 41(1), 111–122.

Midtsundstad, T. I. (2011). Inclusive workplaces and older employees: An analysis of companies’ investment in retaining senior workers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(6), 1277–1293.

Sargent, L. D., Lee, M. D., Martin, B., & Zikic, J. (2013). Reinventing retirement: New pathways, new arrangements, new meanings. Human Relations, 66(1), 3–21.

Sen, A. (2009). The idea of justice. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Simpson, P., Greller, M., & Stroh, L. (2002). Variations in human capital investment activity by age. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61, 109–113.

Snape, E., & Redman, T. (2003). Too old or too young? The impact of perceived age discrimination. Human Resource Management Journal, 13(1), 78–89.

SOU. (2013:25). Slutbetänkande av pensionsåldersutredningen- Åtgärder för ett längre arbetsliv [Measures for longer working life]. Report SOU 2013:25. Government Offices of Sweden.

Trethewey, A. (2001). Reproducing and resisting the master narrative of decline: Midlife professional women’s experiences of aging. Management Communication Quarterly, 15(2), 183–226.

Wikström, E., & Liff, R. (2019). Chefens betydelse för ett längre arbetsliv [The importance of the manager for a longer working life]. Underlagsrapport till Delegationen för senior arbetskraft rapport, 10(S 2018), 10.

Wikström, E., Eriksson, E., Karamehmedovic, L., & Liff, R. (2018). Knowledge retention and age management: Senior employees’ experiences in a Swedish multinational company. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(7), 1510–1526.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wikström, E., Allard, K., Arman, R., Liff, R., Seldén, D., Kadefors, R. (2022). Organisational Capability for Delayed Retirement. In: Falk Erhag, H., Lagerlöf Nilsson, U., Rydberg Sterner, T., Skoog, I. (eds) A Multidisciplinary Approach to Capability in Age and Ageing. International Perspectives on Aging, vol 31. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78063-0_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78063-0_16

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-78062-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-78063-0

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)