Abstract

Toivo’s chapter systematizes prayer as experience on three levels, as everyday encounters, as social processes and as structures. It shows the material and the corporeal nature of the early modern prayer to play an essential part in the ways the religious experience of a prayer was simultaneously constructed and personalized and shared. Praying was ‘doing’ in a much more holistic sense than merely saying words or even less thinking thoughts to God. The body and the material surroundings of the prayer form a space where the experience takes place, even ‘a tool’ to experience with.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

In 1676, Agata Pekantytär stood before the rural district court in Ulvila, west coast of Finland, at the time part of Sweden, accused of witchcraft and magic in fishing, among other things. Her maid testified to her suspicious fishing habits, telling how Agata had cut three eyelets from each of her neighbours’ nets and tied them to her own. In her defence, she asked her maid: “Do I not mention God, too, sometimes?” And indeed, the maid cited a rhyme Agata used when casting those nets: “Eyes of pike, eyes of salmon, eyes of every fish, look into my nets, in the name of the Father, Son, etc.”Footnote 1

As Agata offered her words in defence against charges of witchcraft, she also suggested they would be interpreted as a godly prayer—something clearly incompatible with witchcraft. The court, however, apparently interpreted her words and actions as a charm and, “according to her own confessions”, fined her the considerable sum of 40 marks.

Many witches seem to have offered their use of prayer as a defence. Wallborg Andersdotter from Lapua confessed to “curing toothache with salt, of helping mothers in labour with natural means and by reading the Lord’s Prayer upon them, but nothing else”.Footnote 2 She was also convicted, because she admitted to using the Catholic practices of salt and sequential prayers. Similarly, one can find court cases of superstition and witchcraft where the accused had cited the Lord’s Prayer or the Hail Mary, sometimes also the Creed: the discussion in court then revolved around whether this was prayer or superstition. Historians have used cases like these to study witchcraft and good or evil magic, Christianity and animism, Protestantism and Catholicism, and their popular and elite conceptions. These discussions have, for some time now, often included discourses of “lived experience”, which is often understood as “how things really were” in the past, in contrast to how they should have been according to the norms and ideals of the past.

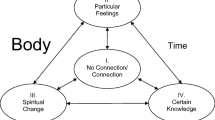

These narratives belie an array of different types of experiences of prayer, of the same events and circumstances. This chapter focuses on the systematization of some aspects of these different experiences along with the three levels of experience described in the introductory chapter of this volume—everyday experience, experience as a social process, and experience as a social structure—and analyses how these differences of religious experience were personalized and shared through the materiality of the human body and the surroundings of experience.

Prayer, Experience, and Materiality

Defining prayer was not a simple matter in the seventeenth century, nor is it now. For the pragmatic purposes of my present analysis, I will define prayer as something that fulfils two criteria: first, someone described it as a prayer and, secondly, it is presented as a communication directed to—or at least mentioning—a (Christian) sacred character. There was a lot of disagreement on the proper nature of prayer and the differences between Christian prayer and devilish magic, as well as between proper Lutheran prayer and what the Lutheran clergy called “papist lip service”.Footnote 3 For the analysis of a material experience of prayer, these discussions can be set aside for the moment, as it is not necessary to know what the actions and events described “were really meant to be”; it is more important to analyse how the experience of prayer was created—or how it failed. As will be seen, early modern prayer was understood as a holistic act including not only verbal communication; it was also a physical, bodilyaction, that was preferably communal. The materiality and corporeality that emerge in this context are indeed entangled material practices, to use Karen Barad’s phrase, that constructs the mental as well as the material simultaneously. It is important to understand that such materialities are indeed practices. They are acts, actions that are performed and done: roasting meat and baking bread, brewing ale, kneeling, touching, eating, making sounds, hearing them, and so on.Footnote 4

The experience of prayer is understood as social and cultural on three levels, as described already in the introduction to this volume. It is not a singular occurrence or event even when it is discussed on the everyday level; it is always connected to past memory and future expectation. Moreover, experience is a process of observing the world and its events, connecting these observations to previous ones, and then interpreting them in a way that connects one’s own collection of previous observations to the present one but also to the expectations of the surrounding community or culture. This simultaneous four-way process is, an important part of the structure of my analysis here. The processes of sharing and personalizing experience eventually consolidate into structures of experience.Footnote 5 Understood this way, experience will always include elements of the worldviews of all participants, even those transcultural influences that participate only remotely, like Christianity, Lutheranism, or State power. Therefore, it is not fruitful to try to separate clerical, dogmatic, and lay influences here, nor to split the elite from the popular—rather, experience is about the entanglement of these influences.Footnote 6

The source material used here illustrates this. I use examples from both prayers that are instructed in the church liturgy as well as catechisms and other didactical material, some of it more unofficial than others, and prayers that were described in secular court records in connection to religious misdemeanours or crimes.

A number of catechisms and liturgy books were used to teach people how they were supposed to fulfil their duties towards God in their daily life. These books were usually quite outside the purchasing power of ordinary people. Still, they influenced lay piety, as they were read aloud for various purposes.Footnote 7 While the official catechisms (Luther’s Catechisms and the Finnish translations by Michael Agricola, Paavali Juusten, and Johannes Gezeliuss) were approved by the church, other prayer manuals circulated in manuscript form. While the official material was written and approved by the church censors, other texts were written or copied by the local clergy and kept where they were used, in the rectories and parish church archives.Footnote 8 They tell not only about how the populace was taught to pray, but also about how they did pray. Sometimes they allow a glimpse of how the official generic material was adapted to individual needs, such as was the case with the prayers in Erich Falck’sComfort Book for Expectant Mothers.Footnote 9 While the material is verbal, it gives bodily instructions to kneel, stand up, sing, recite, and listen. The clerical manuals also give some instruction on gestures: blessing, turning to face the parish or the altar, and so on.Footnote 10 The purpose of these materials was to guide emotion and experience, both of the clergy directing the rituals and of the parishioners participating in them.Footnote 11

As religious offences were prosecuted, the court records form another source for early modern religious experiences. Both secular courts and church courts dealt with religious crimes, although one can usually see that if the church courts took up a case and recorded it, it was usually also transferred to the secular courts even before the church law of 1686, which made it mandatory to hand over all cases that could possibly be criminal to the secular courts. Descriptions of the lay prayers can be read in various court records, where the praying practices were sometimes investigated as part of superstitious practices. I have used trial records for religious offences, superstition, and witchcraft in the seventeenth century, and it is usually the second layer of the court record narratives that is useful, although the first layer does actually include prayers, too, at least at the beginning and end of every court session. Corroborating materials can be found in church account books, where the prayers’ donations were recorded, and sometimes, the prayer can be approached through material evidence—by looking at church murals, paintings, and holy or donated objects—but the court records are what I will chiefly examine, namely the records of trials for religious offences and witchcraft.

The material must be looked at against a background of normative theology and law, and it includes various degrees of instruction on how to produce the desired experience so the “authentic”, individual experiences of any participant must remain unreachable. However, in the end, it is that social process of producing experience that I am interested in, the entanglement of influence and experience as the connecting bridge between the individual and the community.

Prayer as a Material, Everyday Experience

My materials contain roughly two kinds of prayers. The first consists of prayers given in normative materials, such as prayer books and catechisms. Their character is more or less prescriptive and normative depending on who wrote and compiled the literature in question, but it was accepted, at least, since the publication of this type of literature was always subject to censorship in early modern Sweden.Footnote 12 The second type of prayers can be found in corrective and punitive rather than prescriptive material: it is most often found in the church and secular court records as a result of prosecutions of a religious offence, in most cases superstition, but sometimes blasphemy, witchcraft, or even heresy—in cases such as Agata’s fishing methods.

The source materials usually record a sequence of words or the verse that was used. The prayer books record the verbal prayers in full. Court record descriptions of prayer cite verbal prayers that were not canonized. These could be verses that were used over and over again in similar ritual situations, such as the fishing prayer used by Agata. Her prayer combined a few verses with an alliteration trochee mode that commanded various kinds of fish to swim into her nets to the standard liturgical statement of exercising power, “in the name of the Father the Son, etc.”, and they were used often enough and in a sufficiently similar form that her maid could recite them in court.Footnote 13

The court record’s description of the prayers reveal they could also be verbal sequences that were adapted ad hoc when the need arose—often a combination of something that remained the same, like an invocation of divine power, and a request for a general blessing and protection for something more situational and conditional, like naming the object that was now in need of curing or protection.Footnote 14 Often the court records also refer to a commonly used religious formula, such as the Lord’s Prayer or the credo, combined with naming the need at hand. Some other examples were less forceful, but still combined a description of a personal action by the user of the prayer with a sanctioned prayer formula. A peasant woman in Åland, who was accused of having made a pact with the devil, confessed to praying for her sick cattle by saying “‘My cow has been robbed of spirit, my cow has been robbed of blood, my cow has been robbed of flesh, but I will give you malt and salt, and you will get your strength back’, and thereafter she read the Lord’s Prayer”.Footnote 15 Nevertheless, the court records also mention quite a number of prayers used to heal or cure illness or to secure protection from beasts without giving any information of their verbal content.

Such prayers illustrate the nature of prayer as lived religion and the process of taking elements of religion and belief, dogma, and ritual, adding everyday needs, and amalgamating the mixture into contingent acts of faith. As such, they formed events or occurrences, the observation and partaking of which left an impression on someone, an experience in the “everyday” meaning of the word.Footnote 16 This is evident from the fact that the modern researcher is familiar with such prayers, because they were treated with suspicion and led to investigation and trials for superstition or worse religious crimes, as not everything in them was according to religious instruction. It seems at first sight that the gap between the normative Lutheran teaching of “how things should have been” and the practical reality of everyday religion in the rural parishes of early modern Finland was vast. However, rather than being readily separable into learned instruction and popular belief, lived prayer seems to form a web of meanings that anchored and connected the various elements that were present in the rural religious life of early modern Finland. It shows lived religion, or in this case, lived prayer, was a dynamic process instead of something stable and given.Footnote 17

Since lived religion, and indeed experience, should be understood as a web of connecting rather than a gap of dividing influences, there is a need to examine these influences more holistically also in the case of prayer. One way to do this is to look past the verbal parts of the prayers and to consider the act of praying as a whole. Indeed, this may be essential for the study of the experience of prayer. Since experience is something that connects past memories to future expectations, it is essential to look at what happened before, during, and after the prayer. What kind of situations did people pray in? Did they do so in regularly recurring rituals, such as in Sunday services or when going to bed every evening, or more or less spontaneously when the need arose? Did they pray in a church or a chapel, at an altar or a holy place, or wherever they happened to be—camping, in the cowsheds, or laying their fishnets? What exactly did they do when they prayed, and what did it lead to?

Looking at the fishing prayer used by Agata Pekantytär, the experience of the prayer started with the need to catch fish, and it went on with the processes of trying to communicate with the supernatural and tie it to the natural by cutting and tying fishnet eyelets and invoking divine power when casting the nets and commanding the fish. According to the court records, Agata’s catch of fish was substantial enough to make her neighbours suspect she might be using witchcraft, while at the same time as she herself seems to have felt blessed.

The court records abound with similar stories. They mention touching and blessing salt—or in some cases bread or dough—and feeding it to those that people prayed for as well as touching those people or things that were prayed for, both in connection to prayer and to forms of magic that did not mention a divine power.Footnote 18 Other records also report kneeling and walking or crawling around those that were prayed for, those that were prayed to, or those one wished to protect.Footnote 19 A telling example comes from the court records of the parish of Huittinen in 1646, where a group of women were indicted for having held a rosary prayer meeting or a “Rosolia”, at a home with the intention of helping a fellow woman in the village whose eyesight was failing. The women had slaughtered a calf and prepared a meal from it with beer on the table, they drank the beer and ate the calf, and they read a sequence of prayers: “The ten commandments, the credo and Our Father, each nine times on their knees and they struck iron on flint stone.”Footnote 20 The significance of the physical action, of doing things, is emphasized in the record.

In the more official instructive materials, praying is “doing” rather than merely saying words and even less thinking thoughts to God. The church liturgies instruct parishioners to stand up and bow their heads, to recite the prayer, and to sing praises afterwards.Footnote 21 Erick Falk’s prayer book for expectant mothers instructs those praying with the labouring mother to hurl themselves down before God.Footnote 22

It is obvious that for the early modern layperson in Finland—and for the clergy—prayer did not consist of words or thoughts alone, but also of actions. Descriptions of prayer include physical, bodily activities. It is safe to say that the early modern layperson’s prayer was a material and mental combination of thought, word, and action. A significant part of the materiality of the experience of prayer consisted of the bodies of both the persons praying and also those of everyone else involved—the beneficiaries, the bystanders, and, at least sometimes, the divine or the holy. Experience is never immediate nor is it ever completely internal or private; it happens in a community and a culture, in a place that is socially defined. An “authentic” experience true to an individual’s self is not only unattainable but it probably never existed, since, as we saw, already the everyday meaning of experience includes pre-existing expectations; it is preconditioned by outside influence and takes place in a web rather than a separation of influence.Footnote 23 Therefore, in order to study the prayer experience, it is important to take into account this physical action with its materiality and its bodily nature.

The process of experience was further defined by what happened later on: it depended on whether the communication with the supernatural appeared successful or not and whether, indeed, it was understood as such by other people, dismissed as nonsense, or, as in Agata’s case, interpreted as speaking God’s name criminally in vain. Experience is then a process of experimenting with and observation of the world, which always includes an attempt to explain and interpret the observations made. This makes experience the “nodal point of the intersection between public language and private subjectivity, expressible commonalities and the ineffability of the individual interior”—everything at once in an inseparable amalgam.Footnote 24 As many of the stories in the court records testify, experience needed to be approved by a community or society. The case descriptions provide evidence of a process in which the events were turned into different types of experience as presented by different parties, either in conflict to or corroborating each other, and where people at least implicitly discuss their evaluations. They determine whether the experience was one of legitimate prayer or forbidden superstition or worse. It is the process of control and approbation or disapprobation that is the focus of this chapter. The rest of this chapter will look at how these experiences were formed and how they were shared, not only through words but also through bodily action and the senses.

The Medium for the Personalization Process of Experience

The unified forms, places, rituals, and words of early modern prayer could be prescribed in catechisms or prayer books, which often gave these directions as straightforward guidelines and commands to think a certain thought, possess a given rationale, and feel a certain emotion. They are in this similar to the devotional literature of medieval Catholicism, the works of which have been interpreted as intimate or affective scripts: they are quite literally directions for the performance of feeling, and through performance the experience of a feeling. By performing certain exercises, by repeating certain words that could function as “emotives”, by gazing at images, and by picturing narratives, people were immersed in devout and Godly feeling.Footnote 25

The early modern prayer books were, however, often less intimate and more patronizing, not so much leading the devout readers’ way to correct emotions but rather giving direct orders of what the rationale of experience should be. Much of the normative material, prayer books, catechisms, and sermon collections also change the direction of the emotions in prayer: moving away from the medieval hope that divine intercession would change the fates of those praying in a better direction, the purpose of Protestant (and to an extent, reformed Catholic) religious prayer was to confirm the convictions that an omniscient and omnipotent God had already arranged everything for the best, and the only sensible thing a faithful Christian could do was to calmly submit to His will. Even the attached thoughts and goals of prayer were often prescribed, since prayer should be humble in its utter undeservingness, yet confident in the knowledge that God will help—and if the help did not always come in the ways human nature hoped for, it was nevertheless a Christian duty to think that it was for the best.Footnote 26

This is well visible in some of the materials from early modern Sweden and Finland. For example, Erich Falck’s prayer book for expectant mothers exhorts mothers to embrace pain and bodily suffering as a grace given by God—it is their chance to take part in the punishment of the sins of Adam and Eve, to console themselves with the result when the baby is born, and to trust in God’s help. If that help seemed to come slowly, it was only to let poor humans properly see His power and the futility of their own effort, and to let humans practice their patience and faith. Experiencing His fatherly discipline and rod should bring women to love Him more when the pain eventually lifted. Should the mother perish in pain, no harm was done: since she died in fulfilling her divine calling of motherhood, she was freed from her sins and her miserable life, and she would enter eternal rest in heaven.Footnote 27 Though the prayers performed by people who appeared in the court records seem to have hoped for rather more immediate relief, there is a strong attempt to guide not only the forms and verbal expressions of prayer, but also the related internal emotions and thoughts and hopes—the whole range of human response that forms experience.

While careful instruction was given on the uniform integration of religious thinking and feeling, both the same instruction and other descriptions of prayer also show that often, material and bodily cues were used to tie prayer back to the personal sphere. This was already visible in the places of prayer, as church prayers took place within the pews assigned to individual households often in an order displaying wealth and status, as well as gender, marital status, and age.Footnote 28

Court records also described prayers in cowsheds, fields, and pastures, and, like Agata’s, in fishing places and hunting grounds. While some forms of prayer took the prayer far, even to the sacrificial churches of other parishes, which demanded long pilgrimage-like journeys to enact the prayer,Footnote 29 most often people prayed where they lived or close by, amid their daily work. While these places were often owned and used commonly by the villagers, they were always connected to the named individual who performed or was the beneficiary of the prayer—or if not to the person, then to the household, meaningful relationships, or a more or less daily task. These were personal, though not private, spaces.Footnote 30 Performing a prayer in these places also connected the prayer to the personal sphere, even when the verbal part of prayer was, word by word, a commonly used Lord’s Prayer. Catechisms and prayer books also instructed prayer in the household, at the meal table and in bedrooms.Footnote 31 This brought the place of prayer into the privately owned, personal, and sometimes intimate sphere.

Bringing prayer to the intimate and personal—if not personalized—places and spaces had the power to make even otherwise common and prescribed prayer personal. Place and space, and indeed time are not to be understood as just the backdrop of action, but parts of the experience of early modern prayer itself. It was not detached from place; place and prayer intra-acted as entangled material practices. As these entanglements took place in certain individual and personal places, the common and shared in them became simultaneous pluralities.Footnote 32

Using the bodies of those who prayed as part of the prayer was an even more powerful way of re-connecting the prayer to personal experience. This did not mean only standing up, kneeling, or prostrating oneself for prayer as was instructed in the prayer books and church liturgies, nor using one’s personal bodily voice to utter the verbal parts of it—or the cries of pain, grief, or joy that may have accompanied the words—things that were done with or came out of the personal body.

Many of the prayers include some form of eating blessed salts, blessed bread (sometimes but not necessarily oblates, although the clergy was certainly worried about the possibility of misusing communion bread),Footnote 33 blessed dough, or blessed milk—or feeding them to sick people or cattle.Footnote 34 These descriptions also combine elements of ritual eating, probably deriving from communion and other celebratory meals. The description above of the women in Huittinen emphasized the organizing of a full meal for a prayer meeting, from slaughtering a calf and brewing the beer to consuming the meal during the prayer meeting.Footnote 35 The unofficial celebrative meal in honour of the saint may also have reflected the Catholic practice of distributing the Eulogiae or blessed (non-consecrated) bread at the back of the church at the end of mass. As the bread was not transubstantiated, consuming it unprepared and unworthily did not pose the same danger of desecration as the real communion bread. It allowed the laity to play a part in the social side of the communion, partaking in community activities enhanced by the common sacred event.Footnote 36 Eating or being eaten was a way of entering the body, and while eating evil or cursed things could pollute the body in witchcraft, so would eating blessed things bless the body and let the sacred powers enter it. Eating blessed bread, milk, or salt was a way of literally internalizing the prayer. This effect is not only discernible in the court records’ testimonies of people who were accused of superstitions; it corresponded to official theology as well: the real presence and the immediate touch of the material manifestations in the communion were important and discussed elements of seventeenth-century Lutheranism.Footnote 37

The use of bodilyaction in prayer also brought attention to the sensory elements of feeling and experience, such as coldness, warmth, smell, and light or darkness, as well as to physical sensations of anxiety and expectation—the pressing or lifting of the heartFootnote 38 that the early modern prayer books recount instead of the modern butterflies in the stomach, or indeed the sense of satiation and fullness or relief related to a successful experience of a helpful prayer meeting.

Attention to the material surroundings and the body emphasizes experience as a social process that is not only an immediate encounter with or an observation of the world, but rather a more or less deliberate effort to gather, produce, and make sense of these observations or encounters.Footnote 39 While experience takes place as a web of influence, this web is anchored to the personal and individual as they are reflected in the surrounding place and space, physical materiality, and the body of those doing the experiencing. While the “authenticity” or immediacy of an individual’s true experience is unattainable and possibly non-existent, some form of authenticity was actually created in the materiality of early modern prayer: there was the successful application of the expected elements of experience to oneself and one’s situation through the material place and the intimate body. Once thus applied, the praying person was able to recognize the experience of prayer as his or her own, as personal and specific, despite it being constructed under cultural and social influences. This is more than William Reddy’s “emotive success”,Footnote 40 which means matching an inward feeling to cultural expectation. Rather, authenticity in experience must mean the process of creating the web of experience in the inner and the contextual together. Like a spider’s web, the web on experience cannot be disentangled: removing almost any part will make the whole web collapse. The inner and the outer of authenticity simply do not exist without each other. Physical and material as well as bodily points of experience serve as the anchor points and joints of that web, authenticating it, but this is an authenticity that is created as the process of experience is carried on, as a result of it, rather than as a base or basic point before the start of the cognitive.

The authenticity here is related to a subjectivity that is also not given, but constantly created in connection—intra-action even—with the rest of the world.Footnote 41 In such a situation, attention shifts between the experiencing subject and the social relationships and interdependencies in which experience is produced. Above, I have looked at the personalizing and “authenticating” of experience. Next, I will look at the sharing of it.

The Medium for Sharing and Structuralizing Experience

In the example of the fishing prayer at the beginning of this chapter, Agata offered her prayer as evidence that she was a good and godly person instead of the evil witch she was accused of being. What her maid had heard when they went fishing, and what the court’s audience heard when the maid recounted it, however, was instead a spell or a charm. When the judge and jury heard it in court, they heard someone at least taking God’s name in vain with superstitious if not evil intent. Even though Agata did catch a lot of fish, the rest of the community did not perceive or experience this as a sign of divine approval or a response to her prayer, but rather as proof that she had indeed engaged in efficient witchcraft that stole the catch from the rest of the villagers. While personal and specific, involving her own body, her own boat, her own fishing nets in the place where her household had a right to fish, her experience cannot be defined as successful. Agata’s experience of what she did and what happened differed from that of her maid and the rest of the villagers. In the evaluation that followed the events, in the local gossip as well as in court, her version of the interpretation was not approved. She lost both the court case, being fined a substantial sum of 40 marks for witchcraft and superstition, and the right to define what had happened.Footnote 42

The experiences around Agata’s fishing prayer could be compared with those of the women organizing the prayer meeting for the woman who was going blind. These women were brought to court likewise on suspicion of superstition. However, what comes forth from the court records is a totally different situation from that in the investigation around Agata and her fishing. Both cases were initiated by the local pastor, but in Agata’s case, she had been first denounced by neighbours and relatives in her village, people who suspected her and were prepared to testify against her. The women in Huittinen, on the other hand, had only come to the attention of the new pastor of the parish because he was appointed to his office. The former pastor was not deceased but only deposed. This was an exceptional circumstance, the former pastor had no wish to leave, and the new one initiated an investigation into the former pastors’ demerits: he was said to drink, quarrel, neglect his office, and hold suspicious religious views. The women were brought to court as evidence against the former pastor, who had not only condoned such superstitious practices—including Catholic Rosary use—but encouraged it. Their testimonies were congruent. Despite strong ritualistic implications in the numbers of prayers and credos repeated, in the meals and in the “striking iron with flint”, no one suggested that it was not a prayer meeting; it was just a slightly erroneous one. In addition, no one contested that the prayer had apparently been heard: the woman going blind had improved as a result. Whereas the court agreed with the new pastor that this was not quite the way a proper prayer meeting should be held, the women were not punished for their action; they were merely sent home and told not to do it again.

The origins of the investigations obviously have an effect on how the investigation went and was described in the court records. The differences in the origins of the court proceedings in turn originate from the differences in the experience of what happened in the respective events of prayer—where, how, and by whom they took place. The one most obvious difference is that Agata performed her fishing prayer almost alone. Agata’s maid had witnessed the prayer often enough for her to be able to recite it word for word in court. Nevertheless, the maid’s experience was markedly different. Conversely, the women in Huittinen shared a similar, united experience. This is centrally related to the physical material and bodily context of praying.

It was Agata who performed the fishing prayer, using her own hands, her own voice, in her own boat at a fishing place to which her household held the rights. She even called the fishnets “my nets”. Her maid watched, helping as she was bound to do by her work contract, but essentially only obeying the commands of her household mistress. The women in Huittinen, on the other hand, acted together. While it is likely that for the sake of convenience, they collected in someone’s house and therefore in a private space, they had prepared a meal and brewed ale together, they ate and drank together, they stood up and knelt down together, and struck iron with flint together, moving and using their bodies at the same time for the same purpose. When they recited their verbal prayers, they did so in (relative) unison.

Experience was part of this process: a bodily sensation of touch, of cold or warmth, or of smell or sight was not necessarily the same for everyone, but there was likely such a sensation for almost everyone, or at least almost everyone had some previous experience that allowed them to imagine such sensations. While not necessarily the same to begin with, these sensations could be assigned meanings that were similar enough to allow people to negotiate a shared interpretation. The body was not only a means of an individual experience of faith and gender, but also a means of sharing and negotiating them with other individuals and whole communities.Footnote 43 The body and the material surroundings were part of what bridged individuals and communities, and transferred one-time actions into rituals and eventually social structures.

We could use Karen Barad’s New Materialist theory, which states that material bodies intra-act on a deeper-than-molecular level, and are “neither individual entities, nor mental impressions, but entangled material practices”.Footnote 44Barad’s theory essentially means that in nature, bodies—or any material objects—have no fixed essence. Rather, they are constantly changing, “coming-to-be” something that is influenced by everything else. Early modern people did not think in terms of quantum physics, but, on a much more practical level, they understood that their surroundings moulded them, and they in turn moulded their surroundings. When thought of in terms of “coming-to-be”, gender and sexed bodies could also refer to maturing and ageing. In particular, female corporeality was unstable because of the reproductive life course; the female body transgressed categories, manifested noncompliance to norms, and signified decay, but as the women in Huittinen proved, female bodies could also bridge, come together, and renew life and well-being. It was the body that was—despite its intimately personal, physically specific, and infinitely variable nature—similar enough for everyone to provide an anchoring point for a shared experience, allowing different individuals to explain their observations and encounters in the world in ways that fit not only the world views of those doing the encountering, but also those of the people around them—their communities, societies, and cultures.Footnote 45

The bridging or sharing of the power of (female) bodies was harnessed in ritual action—in action that could be and was shared often enough and for long enough by a sufficient number of participants to increase its significance. The women in Huittinen cited the Lord’s Prayer nine times. The church, too, used similar rituals during the divine services, having people recite prayer in unison, stand up, kneel, and sit down as a united congregation during the liturgy. Indeed, it was part of Lutheran theology that a shared prayer was more powerful than an individual one, and this is why Rogation day services were compulsory for the whole parish community.Footnote 46 As the ritual processes of experience were repeated often enough by a significant number of people and communities, they began to form social structures that people came to expect, count on, and despair of.Footnote 47

Conclusion

This chapter has explored the experience of prayer on the three levels of experience described in the introductory chapter of this volume—everyday experience, experience as a social process, and experience as a social structure. It has shown the material and the corporeal nature of the early modern prayer to play an essential part in the ways the religious experience of a prayer was constructed, personalized, and shared.

Praying was “doing” in a much more holistic sense than merely saying words or even less thinking thoughts to God. Early modern descriptions of prayer, both in prayer books or liturgies and in lived religion, for example in court records, show clearly that early modern prayer was, indeed, a profoundly bodily process that included touching, kneeling, walking around things, singing, and eating. These descriptions show prayer as a material, physical action that had sensory resonance in the body. The body and the material surroundings of the prayer form a space where the experience takes place, even “a tool” to experience with. The early modern Finns, who prayed, did that with their whole body, kneeling, standing up, and touching either a representative of the object they prayed for—a fishnet or a sick cow—or a representative of the sacred force they prayed to—a blessed meal, blessed salt, communion bread, or a church building. They took their prayer close to the places where the prayer needed to work—to the church but also to their fishing waters, cowsheds, and homes.

As a sense of place is preconditioned by the experiences related to it, the experience of prayer also transformed these places from merely mundane spaces to spaces that had a spiritual and religious aspect to them, just as the places brought hope for a sacred influence on mundane everyday life.

Attention to the material surroundings and the body emphasizes experience as a social process that is not only an immediate encounter with or observation of the world, but rather a more or less deliberate effort to gather, produce, and make sense of these observations or encounters.

The observation that experience is materially situated in a very specific place and often a bodily process draws attention to questions of how personal or authentic experience can be. While “authenticity” in the sense of the direct, unmediated individual’s “true” experience is unattainable—if it even exists—some form of personality and, through it, authenticity was created in the material and bodily “taking place” of the prayer, where the outside social conditions of experience were matched with the personal conditions of one’s intimate world. It is nevertheless worth noting that this type of authenticity is far from a “starting point”, a “real” feeling that could be exposed once all the layers of cultural influence are removed. This is an authenticity that is created as the process of experience is carried out, as a result of it rather than before the start of the cognitive process.

The physical body and the material place were also media of sharing experience. Despite its intimately personal, physically specific, and infinitely variable nature, the body was also similar enough for everyone to provide an anchoring point for a shared experience. The material aspects of the place were likewise something that could be observed and understood in reasonably recognizable ways by different people. Together, they allowed different individuals to explain their observations and encounters in the world in ways that were recognized as a reasonable fit, both by themselves and those around them, their communities, societies, and cultures. This, eventually, allowed for similar enough processes of experience to be shared by significant enough numbers of people to enable them to form social structures that guided and formed the experiences of whole communities and societies. When the bodilyaction of lived religion is reconnected to the cognitive process and mediated discussion of experience with one’s community, the body, too, gains more importance than just as a tool to act with or a container for one’s cognitive processes: the body and material surroundings were part of the process that bridged individuals and communities, and turned one-time actions into understood experiences, and eventually social structures.

Notes

- 1.

“‘Nembnär jagh intet Gudh ibland?’ … ‘Lohen sjlmät, Sijan sjlmät, Minun vercoin Catzocat, Nimen Isen Poian etc.’” District Court records, Ulvila 11–12 Sept 1676; Bielkesamlingen vol. 27: 53–5. SRA.

- 2.

The case was summarized in Åbo Tidningar 23 February 1795 (no. 8).

- 3.

Oja, Varken Gud, 173–177; Nenonen, Noituus, taikuus, 39–72; Ankarloo Trolldomsprocessena, 82–86; Toivo Faith and Magic, 36–40.

- 4.

Barad, Meeting the Universe, 55 f.; Laitinen, Order, Materiality, 23–24.

- 5.

Kivimäki “Reittejä kokemushistoriaan”; Toivo “Kapitalismista kokemukseen”.

- 6.

Katajala-Peltomaa & Toivo, Lived Religion and Gender, 1–24.

- 7.

Laine, “From learning the Catechism”, 138–154; Laine, Aapisen ja katekismuksen.

- 8.

Tapio Salminen, “Kokemäen käsikirjakoodeksi”.

- 9.

Falck, “Tröstebok”.

- 10.

Knuuttila, “Liturginen yhdenmukaistaminen”; Salminen, “Kokemäen käsikirjakoodeksi”; Agricola, Rucouskirja; Agricola, Käsikiria.

- 11.

Malmstedt, Bondertro.

- 12.

Laine, “From learning the Catechism”; Laine, Aapisen ja katekismuksen.

- 13.

District Court records, Ulvila 11–12 Sept 1676; Bielkesamlingen vol 27: 53–5. SRA.

- 14.

See also Eilola, Rajapinnoilla, 65 and 134–135 about naming in spells.

- 15.

“Mijn koo är modstulen, mijn koo är blodstulen, mijn koo är köttstulen, men jagh skall gifwa dig malt och salt, och du skallt få dijn mackt och kraft åther.” District court record draft Kastelholm 6 August 1666 in Hausen 1894–98, 266.

- 16.

Berger & Luckmann, The Social Construction of Reality. See also the “Introduction” for this volume.

- 17.

See for example Hall, Lived Religion in America; Orsi, The Madonna of 115th Street; McGuire, Lived Religion; Norris & Inglehart, Sacred and Secular; Ammerman, “Lived Religion”; Bell, Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice; Moore, Touchdown Jesus and, on Finland, esp. Toivo, Faith and magic.

- 18.

Åbo Tidningar 23 February 1795 (no8); District court records Vehmaa ja Ala-Satakunta II KO a5: Eura, 29 & 31. October. 1695, 524–28; Kokemäki 14–15. June 1633, 230v–232 (new page number 197v–199); 7. December 1633, 266–v, new page number 233–v.; 20.-21. March 1634, 298-v (new page number 264v-5) and 17.-20.11. 1634,336 (new page number 303); Ala-Satakunta II KOa 6: Ulvila 19.-21. October 1691, 530–31; Ala-Satakunta II KOa7: Ulvila 10.-11-October 1692; 471–3. NA.; See also Kastelholm 6. August 1666 in Hausen ‘Ransakningar’, 266–274 and Sund 12.-13. December1666 in Hausen ‘Ransakningar’, 285–293.

- 19.

Konglig Maijt:tz Placat och Påpud; Ståhle, Rannsakningar efter antikviteter. These evaluations are discussed, e.g. by Wangefelt-Ström, Heligt, Hotdullt. District Court Records Ala-Satakunta II, KO a2, Ulvila 11.-13. July 1687. 225–229. NA.

- 20.

“Tio Gods buds, troon, Fadhren wår nio gånger hwardera på knään läsit.” District court records, Ala-Satakunta I KO a6, Huittinen 16.–18. November 1646, 192v. NA.

- 21.

Knuutila, “Liturgisen yhdenmukaistamisen”, 9–40; Laasonen, Luterilaisuus, 73; Malmsted, Bondetro, 145–5.

- 22.

Falck, “Trostebook”, 340–341.

- 23.

Jay, Songs of Experience, 6–7.

- 24.

Jay, Songs of Experience, 6–7; Newton, Misery to mirth, 28–30; Millard, 2020, 194ff.; Boddice and Smith, Emotion, Sense, Experience, 30–31.

- 25.

McNamer, Affective; Reddy, Navigation; Scheer, “Are feelings”; Katajala-Peltomaa, Demonic Possession.

- 26.

Karant-Nunn, Reformation of feeling; See also Atherton, “The pursuit of power”.

- 27.

Falck, “Tröstebok”, 314–319, 324–331.

- 28.

Saalasti, Penkkisijakiistat.

- 29.

Kuha, Pyhäpäivien vietto, 91–102; Toivo, Faith and Magic, 50–60.

- 30.

Laitinen, “Materiaalinen kaupunki”.

- 31.

Agricola, Rucouskiria, Bibliasta; Getzelius, Yxi Lasten Paras Tawara.

- 32.

Barad, Meeting the Universe, 55 f.; Laitinen, Order, materiality, 23–24; Jerram, “Space: a Useless Category”, 408, 419; Barclay, “New materialism”.

- 33.

Laasonen, Johannes Gezelius, 227–8; Gezelius, Casuum conscientiae, 302, 303. Kicko-Laki 1686 XI: 10.

- 34.

District Court Records Ala-Satakunta II, KO a6: Ulvila 19.-21. October 1691, 530–31; Ulvila 10.–11. October 1692. Ala-Satakunta II, KO a7:471–73. Kastelholm 6 August 1666 in Hausen, “Ransakningar”, 266.

- 35.

“Tio Gods buds, troon, Fadhren wår nio gånger hwardera på knään läsit”, District court records. Huittinen 16.–18. November 1646. Ala-Satakunta I KO a 6, 192v. NA.

- 36.

Bossy, “Blood and baptism”; Burnett, “The Social History of Communion”, 87–8; Kuha, Pyhäpäivien vietto, 88–90.

- 37.

Getzelius, Perbreves.

- 38.

Eyice, An emotional landscape, 60–63.

- 39.

Koselleck, “Der Einfluß der beiden Weltkriege auf das soziale Bewußtsein”, in Der Krieg des kleinen Mannes: Eine Militärgeschichte von unten, ed. by Wolfram Wette (München: Piper, 1992), esp. 324–32. Backman, “Äärellisyyden kohtaaminen”, 26–27; Toikkanen, “Välineen käsite”; Toikkanen & Virtanen, “Kokemuksen käsitteen ja käytön jäljillä”, 7–24; Scott, “Evidence”. See also the “Introduction” to this volume.

- 40.

Reddy, Navigation; Boddice and Smith, Emotion, Sense Experience, 31–32.

- 41.

Mack, “Religion, Feminism”; Eustace, Passion; Boddice and Smith, Emotion, Sense Experience, 25–6.

- 42.

“‘Nembnär jagh intet Gudh ibland?’ … ‘Lohen sjlmät, Sijan sjlmät, Minun vercoin Catzocat, Nimen Isen Poian etc.’” Bielkesamlingen vol. 27: District Court records, Ulvila 11–12 Sept 1676, 53–5. SRA.

- 43.

See also Mahmood, Politics of piety and Ahmed, “Some Preliminary Remarks”.

- 44.

Barad, Meeting the Universe, 55 f.

- 45.

Koselleck, “Der Einfluß der beiden Weltkriege”, 324–32. Backman, “Äärellisyyden kohtaaminen”, 26–27; Toikkanen, “Välineen käsite”; Toikkanen & Virtanen, “Kokemuksen käsitteen ja käytön jäljillä”, 7–24; Scott, “The Evidence”.

- 46.

Schmedemann 1709, 453–454; Lempiäinen, Pyhät ajat, 217–222; Kuha, Pyhäpäivien vietto, 64–66; Malmstedt, “In defence”.

- 47.

Koselleck, Futures Past.

Bibliography

Archival Material

District court records: Ala-Satakunta I and II, National Archives of Finland. Helsinki.

Bielkesamlingen vol. 27: 53–5. Sveriges Riksarkiv. Stockholm.

Printed Primary Sources

Åbo Tidningar, 23 February 1795.

Agricola, Mikael. Käsikirja Castesta ia Muista Christikunnan Menoista. Stockholm, 1549.

Agricola, Mikael. Rucouskiria, Bibliasta: se on, molemista testamentista, messuramatusta, ia muusta monesta, jotca toysella polella luetellan, cokoonpoymettu Somen Turussa 1544. Stockholm: Amund Lauritsanpoika, 1544.

Falck, Erik. “Erik Falcks Tröstebok till hafvande kvinnor.” In Terhi Kiiskinen, Fem källor från den svenska reformationstiden in Finland. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 2010.

Getzelius, Johannes. Yxi Lasten Paras Tawara. 1666.

Gezelius, Johannes. Perbreves commonitionis eller Korta Påminnelser. Turku: Royal Academy Print, 1673.

Gezelius, Johannes. Casuum conscientiae et praecipuarum qvaestionum practicarum decisiones. Turku: Royal Academy Print, 1689.

Hausen, Renhold. “Ransakningar och domar rörande Trolldomsväsendet på Åland 1666–1678.” In Reinhold Hausen (ed.), Bidrag till Finlands historia II. Helsingfors: Finlands Statsarkiv, 1894–1898.

Kircko-laki ja ordningi (1686). In Faximile and edited print by Lahja-Irene Hellemaa, Anja Jussila and Martti Parvio, eds. Helsinki; Finnish Literature Society, 1986.

Konglig Maijt: tz Placat och Påpud, Om Gamble Monumenter och Antiquiteter. Tryckt aff Georg Hantsch, 1666.

Schmedemann, Johan. Kongliga stadgar, förordningar och resolutioner ifrån åhr 1528 in til 1701. Upsala, 1706.

Secondary Sources

Ahmed, Sara. “Some Preliminary Remarks on the Founding Gestures of the New Materialism.” European Journal of Women’s Studies 15 (2008): 23–39.

Ammerman, Nancy T. “Lived Religion.” In Emerging Trends in Social and Behavioral Sciences, edited by Robert A. Scott, Stephen M. Kosslyn, and Marlis Buchmann, no pagination. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118900772.etrds0207.

Ankarloo, Bengt. Trolldomsprocessena I Sverige. Lund: Skrifter utgivna av Institutet för rättshistorisk forskning, Serien I, 36:e bandet. Lund: Rätsshistoriska institut, 1972.

Atherton, Ruth. “The pursuit of power: Death, Dying and the quest for social control in the Palatine 1547–1610.” In Dying, Death, Burial and Commemoration in Reformation Europe, edited by Elisabeth Tingle and Jonathan Willis, 25–48. Farnham: Routledge, 2016.

Backman, Jussi. “Äärellisyyden kohtaaminen: kokemuksen filosofista käsitehistoriaa.” In Kokemuksen tutkimus VI: Kokemuksen käsite ja käyttö, edited by Jarkko Toikkanen and Ira A. Virtanen, 25–40. Rovaniemi: Lapland University Press, 2018.

Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke university Press 2007.

Barclay, Katie. “New Materialism and the New history of Emotions”. Emotions: History, Culture, Society 2017:1. 161–183.

Bell, Catherine. Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Berger, Peter, and Thomas Luckmann. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. New York: Doubleday, 1966.

Boddice, Rob, and Smith, Mark. Emotion, Sense, Experience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Bossy, John. “Blood and Baptism: kinship, community and Christianity in Western Europe from the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries.” In Sanctity and Secularity: The Church and the world, edited by Derek Baker, 129–143. Studies in Church history, Vol. X. Oxford: Ecclesiastical History Society, 1973.

Burnett, Amy Nelson. “The Social History of Communion and the Reformation of the Eucharist.” Past & Present 211, no. 1 (2011): 77–119.

Eilola, Jari. Rajapinnoilla: Sallitun ja kielletyn määritteleminen 1600-luvun jälkipuoliskon noituus- ja taikuustapauksissa. Bibliotheca historica 81. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 2003.

Einonen, Piia, and Petri Karonen, eds. Arjen Valta: Suomalaisen yhteiskunnan patriarkaalisesta järjestyksestä myöhäiskeskiajalta teollistumisen kynnykselle (v. 1450–1860). Historiallinen Arkisto 116. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 2002.

Ericsson, Peter, ed. Gud, konung och undersåtar: Politisk predikan i Sverige under tidigmodern tid. Opuscula Historica Upsaliensia 35. Uppsala: Uppsala University, 2007.

Eustace, Nicole. Passion is the Gale: Emotion, Power, and the Coming of the American Revolution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Eyice, Mari. An Emotional Landscape of Devotion: Religious Experience in Reformation-period Sweden. Turku: Iloinen tiede, 2019.

Hall, David D., ed. Lived Religion in America: Toward a History of Practice. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Heal Bridget. “Lutheran baroque: The Afterlife of a Reformation Altarpiece.” Art History 40, no. 2 (2017): 358–379.

Heal, Bridget. A magnificent faith: Art and Identity in Lutheran Germany. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Jay, Martin. Songs of Experience. Berkeley: California University Press, 2006.

Jerram, Leif. “Space: A Useless Category for Historical Analysis?” History and Theory 52, no. 3 (2013): 400–419.

Karant-Nunn, Susan. The Reformation of Feeling: Shaping the Religious Emotions in Early Modern Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Karonen, Petri. Pohjoinen suurvalta: Ruotsi ja Suomi 1521–1809. Helsinki: WSOY, 1999.

Katajala-Peltomaa, Sari, and Raisa Maria Toivo. Lived Religion and Gender in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe. London: Routledge, 2021.

Katajala-Peltomaa, Sari. Demonic Possession and Lived Religion in Later Medieval Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2020.

Kivimäki, Ville. “Reittejä kokemushistoriaan: Menneisyyden kokemus yksilön ja yhteisön vuorovaikutuksessa.” In Eletty historia: Kokemus näkökulmana menneisyyteen, edited by Johanna Annola, Ville Kivimäki, and Antti Malinen, 9–38. Tampere: Vastapaino 2019.

Knuutila, Jyrki. “Liturgisen yhdenmukaistamisen toteutuminen Suomessa reformaatiokaudella 1537–1614.” In Suomen kirkkohistoriallisen seuran vuosikirja 77, edited by Hannu Mustakallio, 9–40. Helsinki: Suomen kirkkohistoriallinen seura, 1987.

Koselleck, Reinhart. “Der Einfluß der beiden Weltkriege auf das soziale Bewußtsein.” In Der Krieg des kleinen Mannes: Eine Militärgeschichte von unten, edited by Wolfram Wette, 324–343. München: Piper, 1992.

Koselleck, Reinhart. Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time. Translated by Keith Tribe. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004 [German original 1979].

Kuha, Miia. Pyhäpäivien vietto varhaismodernin ajan Savossa (vuoteen 1710). Jyväskylä: Jyväskylän yliopisto, 2016.

Laasonen, Pentti. Johannes Getselius Vanhempi ja suomalainen täysortodoksia. Helsinki: Suomen kirkkohistoriallinen seura, 1977.

Laasonen, Pentti. Luterilaisuus Rooman ja Geneven välissä. Helsinki: Suomen kirkkohistoriallinen Seura, 1998.

Laine, Esko M. “Yksimielisyys—sota—pietismi: Tutkimuksia suomalaisesta papistosta ja yhteiskunnasta kolmikymmenvuotisesta sodasta pikkuvihaan.” Unpublished PhD Diss., University of Helsinki, 1996.

Laine, Tuija. Aapisen ja katekismuksen tavaamisesta itsenäiseen lukemiseen: Rahvaan lukukultuurin kehitys varhaismodernina aikana. Historiallisia tutkimuksia 275. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2017.

Laine, Tuija. “From learning the Catechism by heart towards independent reading.” On the Legacy of the Reformation in Finland: Societal perspectives, edited by Kaius Sinnemäki, Anneli Portman, Jouni Tilli, and Robert H. Nelson, 138–154. Studia Fennica Historica 25. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 2019.

Laitinen, Riitta. “Materiaalinen kaupunki: Kodin tilat ja kaupunkiyhteisö 1600-luvun Turussa.” Historiallinen aikakauskirja 117, no. 2 (2019): 137–145.

Laitinen, Riitta. Order, Materiality, and Urban Space in the Early Modern Kingdom of Sweden. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017.

Lappalainen, Jussi. Sadan vuoden sotatie: Suomen sotilaat 1617–1721. Helsinki: Suomen kirjallisuuden seura, 2001.

Lempiäinen, Pentti. Pyhät ajat. Helsinki: Kirjapaja, 2008.

Mack, Phyllis. “Religion, Feminism, and the Problem of Agency: Reflections on Eighteenth-Century Quakerism.” In Women, Gender and Enlightenment, edited by Sarah Knott and Barbara Taylor, 149–177. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Mahmood, Saba. Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Malmstedt, Göran. Bondetro och Kyrkoro: Religiös mentalitet i stormaktstidens Sverige. Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2002.

Malsmtedt, Göran, “In Defence of the Holy Days: The peasantry’s Opposition to the Reduction of Holy Days in Early Modern Sweden.” Cultural History 3, no. 2 (2014): 103–125.

McGuire, Meredith B. Lived Religion: Faith and Practice in Everyday Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

McNamer, Sarah. Affective Meditation and the Invention of Medieval Compassion. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press 2010.

Millard, Chris. “Using Personal Experience in the Academic Medical Humanities: A Genealogy.” Social Theory and Health 18 (2020): 184–198.

Moore, R.L. Touchdown Jesus: The Mixing of Sacred and Secular in American History. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2003.

Nenonen, Marko. “Juokse sinä humma.” In Maata, jäätä kulkijoita. Tiet, Liikenne ja yhteiskunta ennen vuotta 1860, edited by Tapani Mauranen, 143–367. Helsinki: Edita, 1999.

Nenonen, Marko. Noituus, taikuus ja noitavainot: Ala-Satakunnan, Pohjois-Pohjanmaan ja Viipurin Karjalan maaseudulla 1620–1700. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 1992.

Newton, Hannah. Misery to mirth: Recovery from Illness in Early Modern England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Oja, Linja. Varken Gud eller natur: Synen på magi i 1600- och 1700-talets Sverige. Stockholm: Academisk Bokförlag, 1999.

Orsi, Robert. The Madonna of 115th Street: Faith and Community in Italian Harlem, 1880–1950. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985.

Reddy, William. The Navigation of Feeling: A Framework for the History of Emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Saalasti, Markku. “Penkkisijakiistat Suomessa 1600–1700-luvulla.” Masters Thesis, University of Helsinki, 1984.

Salminen, Tapio “Kokemäen käsikirjakoodeksi F1 (1548–1549): Näkökulmia reformaatiokauden kirkkokäsikirjasidoksen paikalliseen käyttöhistoriaan ja ajoitusmahdollisuuksiin.” Suomen kirkkohistoriallisen seuran vuosikirja 98, edited by Mikko Ketola Tuija Laine, 21–45. Helsinki: Suomen kirkkohistoriallinen seura, 2008.

Schild, Georg, and Anton Schindling, eds., Kriegserfahrungen—Krieg und Gesellschaft in der Neuzeit: Neue Horizonte der Forschung. Paderborn: Schöningh, 2009.

Scott, Joan. “The Evidence of Experience.” Critical Inquiry 17, no. 4, 1991: 773–797.

Ståhle, Carl Ivar. Rannsakningar efter antikviteter, band I: Uppland, Västmanland, Dalarna, Norrland, Finland, Häfte I. Kungl. Visby: Vitterhetsakademien, 1960.

Toikkanen, Jarkko. “Välineen käsite ja välinemääräisyys 2010-luvulla.” Media & viestintä 40, no. 3–4, (2017): 69–76.

Toikkanen, Jarkko, and Ira A. Virtanen. “Kokemuksen käsitteen ja käytön jäljillä.” In: Kokemuksen tutkimus VI, Kokemuksen käsite ja käyttö, edited by jarkko Toikkanen and Ira A. Virtanen, 7–24. Rovaniemi: Lapland University Press, 2018.

Toivo, Raisa Maria. Faith and Magic in Early modern Finland. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

Toivo, Raisa Maria. “Kapitalismista kokemukseen eli uskon(non) merkitys yhteiskuntahistoriassa.” In Varhaismodernin yhteiskunnan historia: Lähestymistapoja yksilöihin ja rakeinteisiin, edited by Riikka Miettinen and Raisa Maria Toivo, 125–154, 248–258. Gaudeamus, 2021.

Toivo, Raisa Maria. Witchcraft and Gender in Early Modern Society: Finland and the Wider European Experience. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008.

Wangefelt-Ström, Helena. Heligt, Hotfullt Historiskt: Kulturarvifieringen av det katolska i 1600-talets Sverige. Masters thesis, Uppsala Universitet, 2011.

Wiesner Merry. Women and Gender in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Toivo, R.M. (2022). Prayer and the Body in Lay Religious Experience in Early Modern Finland. In: Katajala-Peltomaa, S., Toivo, R.M. (eds) Histories of Experience in the World of Lived Religion. Palgrave Studies in the History of Experience. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92140-8_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92140-8_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-92139-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-92140-8

eBook Packages: HistoryHistory (R0)