Abstract

High-Growth Enterprises (HGEs) have received growing interest from entrepreneurship scholars, the business press, and of course policymakers. HGEs can potentially make large contributions to economic growth, which has led to various policy initiatives. This chapter discusses the main topics surrounding policy interventions for HGEs, including a discussion of the various rationales for policy interventions. We next discuss the many areas that relate to possible HGE policy instruments. We then evaluate some previous HGE policy instruments, discuss some that have been successful, and possible areas for improvement. Our main policy suggestions are critical listening to stakeholders by policymakers, identifying the decision points (e.g., growth trigger points) to leverage the impact of growth stimuli, designing incentives in the spirit of up or out dynamics, and enhancing the coordination of HGE policies.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

National governments and international organizations are showing increasing interest in High-Growth Enterprises (HGEs) as a source of economic dynamism and growth (Grover Goswami et al., 2019; Flachenecker et al., 2020; Benedetti Fasil et al., 2021) as well as innovation (Veugelers et al., 2018) and the creation of high-skill jobs (Reypens et al., 2020). Scholars have suggested that the state could take an “entrepreneurial” role with regard to investing in emerging HGEs in order to stimulate innovation and entrepreneurship (Link & Scott, 2010; Mazzucato, 2011). This chapter contributes to this area by discussing which policy instruments are appropriate for HGE policy. As we will see, a large number of policy areas should be taken into account when considering HGE policy. As a consequence, a challenge for HGE policy is to coordinate the many existing initiatives from small- and medium-sized enterprise (SME) policy and entrepreneurship policy such that they can be evaluated accurately and implemented more effectively.

This chapter begins by setting out some stylized facts on HGEs and discussing the key issues and rationales surrounding HGE policy (Sect. 2). We then discuss the various areas relating to HGE policy instruments, ranging from areas such as finance, innovation, skills to labor market regulation. HGE policies have had varying levels of success, and in Sect. 3 we try to identify some success stories as well as areas for improvement, and suggest some explanations for what works well and what does not. Our main policy suggestions (Sect. 4) are that policymakers should engage in critical listening to stakeholders, that HGE policy should identify the decision points (e.g., growth trigger points) to leverage the impact of growth stimuli, that HGE policies require incentives that are set up consistent with up or out dynamics, and that HGE policies should be coordinated across government departments to reach a common goal.

2 HGE Policy Instruments

2.1 Stylized Facts on HGEs

Policy discussions about providing support for HGEs need to take into account a number of stylized facts and basic considerations about the nature of HGEs, which are presented here.

-

A small number of HGEs create a large share of new jobs. This is a classic finding from research into firm growth, with for example 4% of firms being observed to create 50% of the jobs (Storey, 1994; Bravo-Biosca et al., 2013; Bravo-Biosca, 2016; Hallak & Harasztosi, 2019).

-

HGEs tend to be young but are not necessarily small. The first 5 years of a firm’s life correspond to a period of unusually rapid growth (Haltiwanger et al., 2013; Coad et al., 2018). For this reason, HGE policies in various E.U. member states have focused specifically on young firms (Flachenecker et al., 2020, p. 43). HGEs are particularly uncommon among old micro firms (Coad & Karlsson, 2022).

-

HGEs are found in all industries (Henrekson & Johansson, 2010) and are, if anything, less common in research and development (R&D)-intensive manufacturing industries (Daunfeldt et al., 2016), although they are over-represented in knowledge-intensive service industries (i.e., service industries with a high share of human capital, Daunfeldt et al., 2016). HGE policy should therefore avoid focusing too much on high-tech sectors (Mason & Brown, 2013), and instead focus on innovative activity more broadly defined, which extends beyond high-tech manufacturing sectors to include knowledge-intensive industries.

-

Rapid growth is not persistent for individual firms. Therefore observing which firms grew fast in the past will not give useful insights about their future HGE status. In this sense, it is better to think of high-growth episodes rather than high-growth firms (Grover Goswami et al., 2019). The low persistence of high-growth status is a difficult challenge for policymakers seeking to target HGEs (Grover Goswami et al., 2019).

-

Rapid growth may be persistent at the regional level, in the sense that regions with above-average HGE shares in one period may be expected to have above-average proportions of HGEs in the next period (Friesenbichler & Hölzl, 2020). This persistence of HGEs at the regional level contrasts with the lack of persistence at the firm level, and suggests there could be a role for locally embedded culture and entrepreneurial institutions in facilitating HGEs.

-

HGEs are heterogeneous. A plethora of different HGE definitions can be found in the literature.Footnote 1 Findings from one sample cannot easily be generalized to others. For example, findings of entrepreneurial learning among a sample of venture capital recipients (Gompers et al., 2010) may not be very relevant for discussions of entrepreneurial learning among entrepreneurs escaping unemployment.

-

HGEs are difficult to predict, both for government policymakers and also for venture capitalists. The approach taken by venture capitalists is to inspect a large number of detailed applications, from which they select a broad portfolio, in the hope that one or two firms receiving investments will become blockbuster hits that can cross-subsidize the losses of the other portfolio firms. Therefore, we argue that the responsibility should not be on policymakers to identify HGEs (in the context of a targeted HGE policy), but instead potential HGEs should be able to self-select into the fast track (if they believe that is where they should be), where the fast track is an up-or-out type of policy environment that can give a valuable boost to ambitious growth-oriented firms although it is not a comfortable place to linger for less ambitious firms.

2.2 Rationales for Policy Intervention

Rationales for policy intervention include the improvement of existing institutions and infrastructure to support businesses (including HGEs), as well as interventions that are targeted more toward removing barriers and providing assistance to certain subgroups of HGEs (e.g., young HGEs or HGEs from certain technological sectors), and another category of policies that seeks to awaken in potential HGEs ambitions for rapid growth.

Improving the infrastructure and institutions for business can improve the conditions for HGEs (and for business more generally). This could include upgrading existing infrastructure and the labor force’s skill base (e.g., transport, broadband in rural areas, education), removing barriers to growth, such as streamlining and simplifying bureaucratic procedures, and facilitating growth such as through export assistance or the removal of export barriers (e.g., in the case of the E.U. single market and the E.U. single digital market). We can also mention here attempts to alleviate information asymmetries that affect the financial sector and may disproportionately affect new small firms.

Deregulation is often heralded as a way of improving the business environment, although we should remember that regulations were often set up with good reasons in mind (a better world would perhaps have fewer rules, but better rules).

Beyond the provision of universal infrastructure are policy interventions that target specific categories of firms. An example is the case of young firms: Many policy measures to support HGEs give privileged treatment to young firms (Flachenecker et al., 2020, see their Table 5 on p. 42). HGEs may also be targeted to promote emerging technologies (Flachenecker et al., 2020, p. 43), although targeting HGEs here would be less effective if targeted at specific sectors than if focused instead on firm-level innovation capabilities (because many HGEs are not in high-tech sectors, Mason & Brown, 2013; Daunfeldt et al., 2016).

A final, and more controversial, category of policy interventions consists of providing highly targeted relationship-based support to potential HGEs (“relational” support in Brown & Mawson, 2016), which could require large investments of policymakers’ attention, and also be ineffective if HGEs cannot be predicted in advance. Similarly, we can mention efforts to awaken in potential entrepreneurs’ growth ambitions that they did not previously have, for example through entrepreneurship education programs that seek to teach entrepreneurial skills to a broad audience. While it has been observed that some firms are sleeping gazelles (i.e., potential HGEs) in the sense that they have high profits but are not engaging in employment growth (Bornhäll et al., 2015), nevertheless it is not clear whether a policy intervention could be set up to turn these sleeping gazelles towards rapid growth.

2.3 Key Issues Regarding HGE Policy Instruments

Four main issues are discussed in this subsection regarding HGE policy instruments.

First, HGEs have urgent needs. Rapid growth is accompanied by higher costs. For example, HGEs are more likely to have their loan applications refused, and face higher interest rates for loans than slower-growing firms (Rostamkalaei & Freel, 2016). Rapid-growth firms may also have lower survival rates (Zhou & van der Zwan, 2019; Coad et al., 2020). Therefore, policy interventions need to act fast. Policy instruments such as tax credits may be more suitable for mature established firms, which can afford to wait until the end of the tax year to receive the benefits (Brown et al., 2017). Instead, grants or targeted support schemes through loans guarantees may be more effective for HGEs.Footnote 2 Furthermore, faster payment for SMEs (e.g., the “quickpay reform” that is evaluated in Barrot & Nanda, 2020) could be especially valuable for HGEs. Also, policy efforts to create a venture ecosystem via capital market, venture capital but also diverse debt financing sources such as venture debt are crucial for the fast growing scale-ups. Venture debt in particular helps scale-ups to meet financing needs and reduce equity dilution concerns.

Second, creating a culture of dependency should be avoided. Large amounts of public investment in supporting potential HGEs could result in a culture of dependency, whereby low-quality firms could strategically invest in building networks and connections, and honing their skills in making applications. Brown and Mawson (2016, p. 827) discuss the case of business incubators for science-based firms that generate a “dependency culture” but do not help these firms to prepare for the challenges of facing the market. A culture of dependency would distort incentives, such that low-quality firms overinvest in perfecting their grant applications, while high-quality firms are (temporarily) overtaken.

Third, regulatory change may breed HGEs, even if it is just a change for change’s sake: any regulatory change opens up new opportunities that fast-movers can exploit. When the U.S. government passed the Public Utility Regulatory Policy Act of 1978, for example, independent energy firms became able to sell electricity to the grid, which generated considerable growth opportunities that were snatched up by entrepreneurs (Sine & David, 2003).

Fourth, decisions regarding the selection of which firms actually receive the policy support involve a mix of (1) picking winners; (2) self-selection; (3) milestones; and perhaps (4) randomization.

-

1.

Picking winners refers to the selection of applications and business plans by government officials and/or external experts, often using quantitative performance assessment or subjective assessments of growth ambitions (Roper & Hart, 2013). Possible drawbacks of a picking-winners approach could be that applications take time for applicants to prepare, capabilities in writing an engaging proposal may be different from capabilities required for entrepreneurial success,Footnote 3 and also the individuals making the selection may make imperfect decisions amid uncertainty. Picking winners can be a useful preselection tool to winnow down the pool of applicants, separating out the lower-quality applicants, while not attempting the finer distinctions between higher-quality applicants (McKenzie, 2017).

-

2.

Self-selection can potentially avoid problems of asymmetric information regarding business quality, by letting promising entrepreneurs use their background knowledge of the firm to select into support programs that are of little interest to less-promising entrepreneurs. Important here is clarity and transparency regarding the costs, commitments, and benefits of policy support schemes, to facilitate the cost-benefit analysis for potential applicants (Roper & Hart, 2013). Self-selection schemes should involve a hurdle that is only worth overcoming for high-potential entrepreneurs. This hurdle can refer to the time costs of preparing an application and dealing with bureaucracy,Footnote 4 participation fees, or perhaps options or convertible fees that have negligible cost in the case of full compliance, but that entail costs in the case of incomplete compliance. An example of the latter type of option would be fines for non-participation.Footnote 5

-

3.

Milestones can be useful devices in situations of investments under uncertainty, according to Real Options theory (Klingebiel & Adner, 2015). Milestones make the availability of successive rounds of support conditional on satisfying certain requirements, and shift the problem from picking winners to retaining winners. Milestones can be effective ways of reducing uncertainty as well as motivating participants to keep making progress, and may even help to provide timely support across growth stages (Autio & Rannikko, 2016).

-

4.

Random allocation of support can help when a limited number of places must be allocated to a large number of applicants of almost-equal quality. Another advantage of randomization is that it facilitates the ex-post evaluation of the overall causal effect of the policy (McKenzie, 2017).

2.4 An Overview of Areas Relating to HGE Policy Instruments

Table 1 provides an overview of the previous literature on public policy to support HGEs, which is the literature to which we seek to contribute. It shows that the number of areas relating to possible HGE policy instruments is large, and includes a number of policy areas with potentially conflicting priorities (Bradley et al., 2021) and whose links to HGEs may not be immediately obvious (Acs et al., 2016). We begin with the more obvious policy areas, before discussing some that may be, at first glance, less obviously related to HGE policy.

Finance

Access to finance for SMEs, young firms, and HGEs is a classic area for HGE policy. A fundamental problem for HGE finance arises from asymmetric information: Investors may deem HGEs to be poor investments using traditional indicators, and HGEs may not be able to convince investors of the merit of their business idea. Relevant to our discussion of reducing information asymmetries for (innovative) HGEs, Brown et al. (2017) observed that more R&D investment in high-tech industries is observed in countries that have stronger accounting standards and better contract enforcement. Information asymmetries presumably are a heavier burden for younger firms, which could be why HGE policies in various E.U. member states have focused specifically on supporting young firms (Flachenecker et al., 2020, p. 43).

Bank financing for HGEs is not ideal, because banks would not share in the HGEs’ upside gains in cases of success (banks would receive a fixed interest rate), although banks would bear the brunt of an HGE’s failure (in terms of not recovering the loan). Hence, finance via equity rather than bank loans is more appropriate for risky high-potential ventures. The financial sector now includes a variety of actors that can play a role in supporting the financing needs of HGEs: incubators, accelerators, grants from research councils for basic research, business angels, venture capital (VC) and corporate venture capital, and the relatively recent emergence of crowdfunding. In addition, there are many government initiatives to provide funding to SMEs, young firms, and potential HGEs (such as grants, guaranteed loans, government VC funds, government co-funding, and government certification).

The multiplicity of available options for HGE financing has a number of advantages. HGEs have financing needs that exceed the available bank loans, and therefore they are more likely to apply for equity financing (Ferrando et al., 2019). After reaching a certain leverage ratio, equity type financing helps to improve the balance sheet structure and this way opening up also for new rounds of debt financing. Also, there is evidence that firms that use several financing instruments are more likely to invest in R&D and software activities, and more likely to develop new products (Ferrando & Lekpek, 2018). Crowdfunding and venture capital complement each other (Sorenson et al., 2016), and bank loans and capital markets complement each other (Ferrando & Lekpek, 2018). Private finance is more developed in the United States than in Europe, as highlighted by recent evidence that European startups (compared to U.S. startups) attract 54% less private funding 9 years after foundation (Reypens et al., 2020). Therefore, there is scope in Europe to improve the variety and also the intensity of activity of the various actors in the ecosystem for financing HGEs, perhaps seeking to strengthen in particular the larger later-stage “scale-up” funding rounds as opposed to the smaller early-stage “start-up” funding rounds (Duruflé et al., 2017).

Innovation

According to the Schumpeterian storyline, HGEs are revolutionary movements that begin with a moment resembling spiritual enlightenment, as an entrepreneur suddenly perceives an opportunity to improve the existing economic order, and then brings this innovative idea forward, through a charismatic social movement that gains momentum and eventually replaces the existing socioeconomic order (Nightingale, 2015). In reality, however, most opportunities beheld by entrepreneurs turn out to be mistakes, and many HGEs are not very innovative. Many HGEs are found outside of high-tech sectors, and in fact HGEs are overall less common in R & D-intensive sectors, which are often dominated by large capital-intensive firms (Daunfeldt et al., 2016) although HGEs seem to be more common in knowledge-intensive service industries in which human capital features prominently (Daunfeldt et al., 2016; Ferrando et al., 2019). However, HGEs in sectors that are traditionally considered to be low-tech or medium-tech could thrive through innovative activities such as developing new products and applying high-tech routines and logistics in their sectors (e.g., Walmart in retail, Ikea in furniture, Starbucks in coffee). Therefore, authors such as Mason and Brown (2013) suggest that HGE policies should avoid focusing too much on high-tech sectors.

That said, there is a special interest in HGEs that are innovative, because HGEs play a unique role in bringing forward innovations that could benefit the economy and lead to widespread productivity growth. HGEs represent one of the ways for countries to quickly develop large-scale capabilities and production capacity in an emerging technological area of strategic importance, such as IT, Artificial Intelligence (AI), biotechnology, and autonomous cars. Reypens et al. (2020) find that many European high-growth startups are new-to-the-world innovators, with many adopting innovative technologies (e.g., big data, artificial intelligence) into their businesses. They also find that a large share of high-growth startups expect to increase their demand for high-skilled workers and are expected to prioritize growth over short-term profits. Several HGE support initiatives focus specifically on high-tech HGEs (e.g., Germany’s High-Tech Startup Fund, and Sweden’s National Incubator Program for supporting university spinouts; OECD, 2013).

Innovation policy has a number of instruments that, while not targeted exclusively at HGEs, could provide assistance to HGEs. R & D tax credits are considered to be effective tools for innovation policy (Bloom et al., 2019), although R & D tax credits are more appropriate for mature incumbents than HGEs, because of the delays in receiving the funds (Brown et al., 2017). In the case of HGEs, R & D grants (rather than tax credits) could be more appropriate, whereby the funds are received by firms in advance rather than afterwards. R & D grants could be especially effective if their disbursement is conditional on passing certain project milestones (Flachenecker et al., 2020, p. 48).

Another group of policy instruments relates to the protection of intellectual property rights (IPR), such as the strength of IPR protection, regulations for patents (including expedited patenting, Kuhn & Teodorescu, 2021), technology licensing, technology standards, and so on. Brown et al. (2017) observe that countries with stronger Intellectual Property (IP) protections have higher R & D levels in high-tech industries (whereas the effects of R & D tax credits are mainly confined to mature rather than high-tech industries). There is empirical evidence that higher taxes reduce the quantity and quality of innovations through reduction of R & D investments and patenting (Mukherjee et al., 2017; Akcigit et al., 2022).

Another area for policy intervention relates to science policy and universities. One potential source of high-tech or knowledge-intensive potential HGEs could be academic entrepreneurship (university spinoffs), although the incentives for faculty to leave their stable university jobs depend on whether they possess the IPR over their inventions. Hvide and Jones (2018) show that the abolition of the “professor’s privilege” in Norway (such that university researchers no longer have full rights over their IP) led to a 50% decline in both entrepreneurship and patenting rates by university researchers after the reform. In contrast, the lifting of a ban on businesses run by professors at national universities in Japan is considered to be a success story in terms of high-tech entrepreneurship (OECD, 2019, p. 67).

Business incubators may play a role in HGE policy, although the number of HGEs emerging from business incubators and science parks is generally rather modest, perhaps because many high-tech science-based ventures find their growth constrained by factors such as severe technical and commercial difficulties, lack of educated consumers, and a shortage of high-skilled employees. Lukeš et al. (2019) observed that incubator tenancy had a negligible effect on startup job creation, which casts doubt on the effectiveness of public spending on business incubators. Arauzo-Carod et al. (2018) found that being located in a science and technology park is risky in the sense that it is associated with higher growth for HGEs, but that it is associated with accelerated decline for firms in the lowest growth quantiles. Pena (2004) observes that while some firms in business incubators manage to grow, nevertheless the existence of new firms being supported in business incubation centers may cause the exit of more efficient incumbent firms not receiving such policy support, hence leading to negative externalities for non-recipients.

Skills and Capabilities

Education and skills may also be areas worth considering for HGE policy. At a basic level, a better-educated workforce can be expected to have better skills and capabilities for founding firms that become global leaders. In particular, investments in the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Medicine) sector could be especially worthy of interest from the perspective of HGE policy (Acs et al., 2016). HGEs often report that a constraint on their growth is the availability of a skilled labor force (Ferrando et al., 2019; Reypens et al., 2020).

Besides investment in a country’s education sector, the skills and capabilities of entrepreneurs and the workforce could be enhanced in many areas through mentoring. Mentoring relates to various domains: entrepreneurial skills, management skills, financial skills (e.g., regarding how to access external financing), sales/marketing capabilities, technical assistance regarding planning and implementing investment projects, and so on. González-Uribe and Reyes (2021) present evidence from a causal framework to show that mentors with high business and industry experience can boost the sales growth of mentored startups. Another strategy for boosting entrepreneurial skills could be peer learning that takes place at organized networking events. Cai and Szeidl (2018) present causal evidence that such peer learning boosts firm performance. A problem for HGE policy, however, is that there are no direct policy levers that can boost skills: “no one is in charge of the ecosystem’s skill structure, which limits what can be achieved through top-down reform” (Elert et al., 2017, p. ix). Furthermore, local and national governments should not try to provide training and mentoring if there are already such solutions being provided by the private sector or by the existing entrepreneurial ecosystem.

A “soft instrument” (Borrás & Edquist, 2013) of HGE policy could be to try to influence the informal institutions and public attitudes (Elert et al., 2017; Bradley et al., 2021) in a way that encourages entrepreneurship, in the hope that public attitudes consider self-employment to be an attractive lifestyle, which may potentially lead to the emergence of HGEs. This policy is rather indirect and difficult to evaluate, therefore it should probably not receive large dedicated budgets, although appropriate support and lessons, as well as giving successful entrepreneurs awards and visibility on platforms, could help to gently reorient popular views in a favorable direction.

Labor Market Regulation

Labor market regulation can influence HGEs in a variety of ways, many of which are discussed in Elert et al. (2017). First, Employment Protection Legislation (EPL, i.e., the rules concerning hiring and firing) can reduce the dynamism of labor markets if employers are reluctant to hire new employees (because of the liabilities that this entails), and if employees become accustomed to staying with their existing employers. Second, labor market regulations that start to apply after certain size thresholds (e.g., 50+ employees in the case of France, see Garicano et al., 2016) could cause firms to remain at a small size just beneath the threshold and thus deter HGEs. Third, no-compete agreements could reduce the mobility of employees (especially in high-tech/knowledge-intensive sectors), which could lead to short-term gains from lower leakages of proprietary knowledge on the part of employers, although it also leads to less dynamic labor markets, a possible misallocation of labor (if employees cannot move to exploit new opportunities), and also perhaps a smaller number of corporate spinoffs. It has been claimed that Silicon Valley’s emergence was greatly facilitated by the fact that no-compete agreements are not enforced in California, leading to a vibrant and dynamic labor market (Fallick et al., 2006). Fourth, active labor market policies sometimes provide considerable support to individuals seeking to escape unemployment by becoming an entrepreneur (e.g., Caliendo et al., 2020). However, such entrepreneurs rarely set up HGEs, and it is possible that over-entry of low-quality entrepreneurs crowds out other more promising ventures and causes negative externalities for other entrepreneurs, for example by lowering the average quality of firms in credit markets (De Meza, 2002). Indeed, across countries, there seems to be a “quantity versus quality” type of negative relationship overall between the self-employment rate and various indicators of entrepreneurial performance (Henrekson & Sanandaji, 2014).

Various Other Areas Relating to HGE Policy

Immigration policy is related to the emergence of HGEs (Audretsch et al., 2020), in line with conjectures that individuals who leave their homeland to pursue new opportunities abroad may be more entrepreneurial. Acs et al. (2016) highlight that immigration policy is one of the most important areas for boosting high-quality entrepreneurship.

Tax policy can be relevant for HGE policy because taxes affect the incentives for entrepreneurial and economic choices (Elert et al., 2017). Tax incentives to support HGEs can be broad-based or targeted. An example of the latter is a Romanian initiative that introduced a targeted tax policy initiative to develop capabilities in the IT industry. Employees involved in software programming in Romania were exempt from salary tax. This helped grow a dynamic cluster that included dynamic entrepreneurial firms. Since 2017, the exemption from salary tax was also introduced for R & D employees in Romanian entities (Sincu, 2017).

International trade policy can play a role in supporting HGEs as they plan to grow in new export markets. Indeed, most countries allocate public funds to export promotion (Munch & Schaur, 2018), resulting in many policies to provide export assistance to potential HGEs (Srhoj et al., 2020). HGEs that grow through internationalization may be more competitive (higher productivity, world-class capabilities) and also they do not threaten to displace the economic activity of local firms. There is evidence that HGEs are more internationalized, regardless of whether they export or invest directly in foreign markets, as firms growing rapidly will have more incentives to go abroad (Teruel et al., 2021). Moreover, internationalized companies with new digital technologies may have more capacity to become HGEs. This can be explained by the fact that new digital technologies can generate not only entry opportunities (such as online sales) but also internal capabilities that strengthen firms’ international positioning in competitive international markets (Teruel et al., 2021). Besides growth through exports, HGEs may arise through integrating imports into their production processes (Cruz et al., 2021).

Bankruptcy law could also play a role for HGE policy, according to various scholars (e.g., Elert et al., 2017). There is a danger that capable entrepreneurs may be harshly punished for engaging in what may initially seem like high-risk, high-return entrepreneurial opportunities that are worthwhile bets, but what eventually turn out to be (unlucky) failures. However, there is also a danger that an excessively lenient bankruptcy law could lead to negligence and fraud by entrepreneurs who have little incentive to avoid bankruptcy (Elert et al., 2017). Discussions of bankruptcy law relate to the issue of whether entrepreneurs can learn from failure to become high achievers after a previous bankruptcy. The evidence on this matter, however, often suggests that previously failed entrepreneurs do not learn from their experience in terms of having superior performance with their subsequent venture (Rocha et al., 2015; Nielsen & Sarasvathy, 2016; Gottschalk et al., 2017).

Antitrust policy can support HGEs, by ruling against anticompetitive takeovers and enhancing overall competition, thus lowering the barriers to entry and growth of HGEs.

Government administrative offices could also support HGEs by helping to reduce, wherever possible, the burden of submitting official paperwork. This does not necessarily mean that SMEs and HGEs should give less information on their operations, but that they can do so in a more efficient way (e.g., by secure internet or email or by post rather than appearing in person).

Finally, it is worth mentioning that HGE policy is not only the domain of national policy, but is also influenced by local and regional economic policy (Stam & Bosma, 2015). Within countries, there are considerable disparities across regions in terms of HGE shares, which can be explained in terms of regional concentrations of specific industries often referred to as clusters and competence blocs. Given that some regions have higher shares of HGEs than others, therefore, HGE policy implemented at a local or regional level could be more effective than HGE policy at the national level (Stam & Bosma, 2015).

Reflections on the Many Areas Relating to HGE Policy

Our overview of HGE policy instruments has connected to a variety of areas (education policy, innovation policy, immigration policy, labor market policy, etc.), such that “the interventions required are likely not to sound like entrepreneurship policy” (Acs et al., 2016, p. 49). Another consideration is that many of the policy instruments in the preceding subsections vary from micro-level (e.g., training and mentoring individual entrepreneurs) to macro-level (e.g., reforming national institutions such as tax rates and labor market regulations) (Bradley et al., 2021). Furthermore, the various policy instruments relate to different areas of the economy and society, and are implemented by different government departments and actors (Lundström et al., 2014), with potentially differing considerations, priorities, and trade-offs in mind (Bradley et al., 2021). Effective HGE policy will recognize this complexity.

In sum, there are many areas relevant for HGE policy. As such, various authors have recommended a systemic approach to HGE policy, such that problems affecting HGEs (e.g., access to finance, availability of skilled labor, access to international markets) should not be tackled in isolation, but embedded in a systemic policy framework (Veugelers et al., 2018).

Some good news regarding the effectiveness of HGE policy is that European high-growth startups are more likely than their low-growth counterparts to make use of several forms of public support, and in particular seem to benefit from startup grants/investments (Reypens et al., 2020). This is good news because it suggests that policy support to HGEs might be taken up effectively by HGEs.

3 Best Practices and Areas for Improvement

This section presents some cases of successful HGE policies and contrasts them with less successful HGE policies.

3.1 HGE Policy Instruments that Have Been Successful

Policymakers around the world dream of being able to recreate a Silicon Valley in their countries. An important factor behind the rise of Silicon Valley is the fact that no-compete agreements are not enforced in the state of California,Footnote 6 although they are enforced all over the rest of the United States (Gilson, 1999, 2003; Fallick et al., 2006). As a consequence, disgruntled workers (perhaps high-ability workers who disagreed with their superiors) who left their employers elsewhere in the United States were unable to continue their careers in their home states, but could move to California instead, where no-compete agreements were not enforced.Footnote 7 California therefore benefitted from a large inflow of highly skilled human capital, and furthermore firms in California were able to benefit from a dynamic labor market whereby promising employees were reallocated to top firms. The emergence of Silicon Valley was not due to deliberate government planning (Gilson, 2003), but was largely due to institutional rules (nullifying no-compete agreements) that essentially prevented firms from acting in their short-term interests (Fallick et al., 2006). This also underscores the broad web of institutions and rules that may support the emergence of high-growth entrepreneurship, because the link between no-compete agreements and high-growth entrepreneurship is not especially obvious or direct.

On the European level, several products are offered by the European Investment Fund (EIF) and the European Investment Bank (EIB). The EIF provides risk capital for innovative SMEs in their early stages and expansion phase. It mainly provides financing by partnering with national institutions, through advising, sponsoring, or managing a number of equity Funds-of-Funds and guarantee/debt funds.Footnote 8 Third-party investors include national and regional governments as well as private strategic investors. The objective is to provide a wide choice of financial solutions tailored to complement existing national schemes.Footnote 9 The EIB provides also venture debt as a next step for firms that have already raised venture capital and need additional financing to accelerate growth. Typical use cases include scale-up from pilot to mass manufacturing, further development of products or services through research and development, and international expansion. Also, the European Scale-Up Action for Risk Capital (ESCALAR) pilot program was launched in 2020 by the EIF, specifically for scale-up companies. Developing the venture debt market is a key element of closing the gap of E.U. scale-up funding relative to the United States.Footnote 10 All these instruments are very much in line with those needed by HGEs and several European unicorns (startups that have reached a market valuation of over $1 billion) have emerged from EIF financing programs.Footnote 11

Another modern success story is the development of the venture capital industry in Israel (Avnimelech & Teubal, 2006). Israel’s VC industry is now the global leader on a share-of-GDP basis, and was developed by a government-targeted program. The government set up the industry, overcoming market failures (such as critical mass and asymmetric information), and then withdrew once the VC industry had developed momentum of its own.Footnote 12 An important feature of this success story is that the government got the incentives right for investors: strong upside incentives (with a five-year option to buy the government’s share at cost), although there were no guarantees against downside losses.

Regarding grants for high-growth firms, McKenzie (2017) describes the YouWIN! scheme in Nigeria, according to which grants for high-growth entrepreneurs were randomly allocated to entrepreneurs who had passed some initial preselection stages. Randomization of grants is a simple and powerful tool for distributing grants, that recognizes that the differences between preselected candidates may be small compared to the decision costs (and fees for committees), and also that grant awards may be subject to favoritism or corrupt decision-making. Instead of government bureaucrats picking winners, randomization could provide a fast and transparent method for allocating grants. An added bonus is that randomization makes it easier to identify the causal effects of treatment in the subsequent stage of program evaluation.

3.2 HGE Policy Instruments: Areas for Improvement

Various authors have suggested that boosting the overall rates of entry will lead to more high-growth enterprises, as if increasing the pipeline of entrants will mechanistically lead to a higher number of HGEs (assuming that the conversion rate of entrants to HGEs remains constant). This has resulted in policies seeking to enable entrepreneurs to start their business in a cheap and fast way (Branstetter et al., 2014). However, lowering the barriers to entry will probably only lead to a higher number of lower-quality firms entering (Branstetter et al., 2014; Conti & Roche, 2021). Relevant here is the observation that the better-performing startups tend to choose the legal form of being “incorporated,” which is more expensive than other legal forms such as “sole trader” (Åstebro & Tåg, 2017)—hence making entry cheaper could simply lead to more low-quality sole-trader-type entrants. In general, there is a trade-off between quantity and quality. Countries with higher self-employment rates have lower GDP per capita (Henrekson & Sanandaji, 2014).

In the area of high-growth entrepreneurship, it is crucially important to get the incentives right. Government venture capital funds therefore need to avoid over-protecting investors from the risks of VC investment, even if these investors ask for protection. If losses are heavily guaranteed, while upside incentives are capped at a moderate level, then venture capital schemes can be expected to perform poorly (Gilson, 2003). Also, examples of negative outcomes have been documented in which the VC portfolio firms were managed in a passive rather than active way, with fund managers engaging in minority investments without important control rights, and without provision of mentoring or technological or managerial assistance (Gilson, 2003; Avnimelech & Teubal, 2006; Avnimelech et al., 2010).

While entrepreneurs may request lower tax rates, nevertheless lowering tax rates will not necessarily lead to more HGEs. Tax cuts for capital gains, for example, are unlikely to stimulate additional entrepreneurial activity in a cost-effective way when they are mainly claimed by retiring entrepreneurs who were largely unaware of the scheme when they originally invested (Corlett, 2018). In addition, favorable tax treatment (e.g., inheritance tax relief) for family firms has been identified as a way of allowing low-productivity family firms to continue operations as “zombie firms” even if they earn below-market returns (Bloom & Van Reenen, 2010; also Bloom et al., 2012).

Some other areas for improvement can also be mentioned (OECD, 2013). First, if a program changes its objectives too frequently (e.g., regarding the technological focus of portfolio companies), this can be an obstacle for stakeholders’ development of skills and capabilities. Second, support programs that are perceived as being excessively bureaucratic and slow, with long waiting times for startups from first contact to actually receiving support, could deter high-quality startups. Another bureaucratic hurdle could be that, as a business evolves and pivots and redefines its activities, administrative tracking of these businesses should give them space to maneuver flexibly without requiring excessive official authorization and bureaucratic red tape.

4 Conclusion

We conclude with a discussion of broad themes that cut across various policy instruments and policy areas.

4.1 Critical Listening

Public policy is not as easy as giving stakeholders what they want. Instead, stakeholders should be given what they need to contribute more effectively to the economy and society. Hence, policymakers should be wary of focus groups, communications from industry associations and lobby groups, and survey responses. For example, entrepreneurs and investors may want guarantees against downside losses, or tax cuts, but these have not always been effective ways to encourage investments in high-ambition entrepreneurship. Lowering tax rates for entrepreneurs has not always led to an increase in entrepreneurial performance in the past, and continuing a policy of further tax cuts in our current low-tax era will probably (due to the law of diminishing marginal returns) be even less effective. When Bill Gates started Microsoft in 1975, the top tax rate on income was 70%, and tax rates on capital gains and corporate income were much higher than they are now (The New York Times, 2019). No doubt his calculus for starting Microsoft was not beholden to speculation about the evolution of tax rates. We might even suggest that, in the life cycle of entrepreneurs, initial investments and decisions are made early, and lobbying and grumbling about tax rates are done late in the day (e.g., at the time of retirement and trade-sale), at a stage when changes in tax rates have a weaker effect on incentives or entrepreneurial commitment.

Firms may be keen to see the enforcement of no-compete agreements, but this kind of rational (at the firm-level) yet short-sighted and self-interested (at the ecosystem level) stance may well have stifled the emergence of Silicon Valley (Gilson, 2003; Fallick et al., 2006). Investors may ask the government for downside protection and guarantees against losses, but this risk gives the wrong signals to investors—the danger of losing money if they fail to monitor their investments keeps them sharp and hence adds value (Gilson, 2003). A number of studies of the barriers perceived by firms have shown that barriers include factors such as high levels of competition—but clearly this is not a mandate for policymakers to seek to remove competition. Entrepreneurs often ask for less regulation (e.g., Ferrando et al., 2019), but regulations are often there for good reason. Entrepreneurs want lower taxes, but this is not effective in stimulating HGEs.

Instead, soliciting an audience with certain actors could provide valuable insights. This could involve interviewing not only the success stories, but also the near misses or the dissatisfied. For example, seeking out interviews with firms that left the European Union for later-stage funding in the United States could provide unique insights into the gaps and problems in the E.U. funding landscape.

Therefore, the policymaker needs to have a deeper understanding of the motivations and causal relationships underlying entrepreneurial ecosystems than is visible at a superficial level from self-reported preferences from entrepreneurs.

4.2 Identify the Decision Points

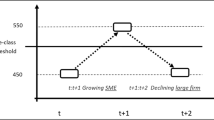

Growth is not a smooth linear expansion but takes place in leaps and jumps, in line with theoretical intuitions that firms are composed of lumpy discrete resources that cannot be combined in perfectly matching multiples (Penrose, 1959). As a result, firms occasionally reach critical trigger points (Brown & Mawson, 2013) at which they may face a decision to either invest in broad-based expansion, or to shrink back to stay within existing capacity limits (Coad et al., 2021). These trigger points include discontinuities in the growth path such as the hiring of the first employee (which corresponds to a doubling of size), crossing critical size thresholds (e.g., regarding Employment Protection Legislation obligations), setting up a second production plant, launching a second product, taking first steps into export markets, and so on. Identifying the trigger points in firms’ growth paths could lead to policy initiatives that effectively nudge firms onto a high-growth trajectory. In this spirit, BPI France launched a scheme to co-finance the investment of firms specifically in the area of game-changing next-generation capital investments (e.g., nanotechnology, 3D-printing, industrial robots, digitalization, and virtual reality applications).Footnote 13

4.3 Up or Out: Get the Incentives Right

Stimulating high-growth entrepreneurship and its supporting institutions (e.g., venture capital firms) requires careful thinking about incentives for the various actors. Getting the incentives right for HGEs requires more than just tax cuts and deregulation. It requires adjusting the balance between upside gains and downside losses. In the case of university spinoffs, for example, restrictions on the commercialization of intellectual property that was developed by faculty in their universities had a dramatic effect of a 50% reduction in university startups and also in patenting rates (Hvide & Jones, 2018). Getting the incentives right also involves broader thinking about incentives and trade-offs surrounding the decision to become an entrepreneur, such as the portability of health insurance (Acs et al., 2016) and pension plans (Elert et al., 2017). No-compete agreements are another area where incentives for corporate spinoffs can be either stifled or unleashed, depending on the incentives facing the would-be entrepreneur.

The logic of ambitious entrepreneurship is not slow accumulation, but rather an up or out dynamic by which entrepreneurs are uncomfortably positioned between the promise of upside gains and the threat of downside losses. HGE policy should not seek to make applicants comfortable with their current performance, but to give them a temporary springboard into growth. HGE initiatives such as science parks, incubators, and accelerators should not allow ventures to persist for long periods of time if they are not showing any signs of progress—instead the logic is up or out. Autio and Rannikko (2016) highlight the importance to HGE policy that ventures are able to meet ambitious milestones before being able to receive further HGE support. Biancalani et al. (2021, p. 18) suggest that startup support programs should be designed to reduce the extent of loan guarantees and to expand the income tax breaks, in order to adjust the incentives facing investors away from protecting downside losses and toward enhancing upside gains. In contrast, Brown and Mawson (2016) discuss the “dependency culture” that may arise in environments set up to support potential HGEs and that end up “killing them with kindness” (Brown & Mawson, 2016, p. 828).

In line with the logic of up or out, young firms should be privileged, because firms in their first five–seven years are much more likely to grow fast (Haltiwanger et al., 2013; Coad et al., 2018). Old SMEs, and particularly old micro firms, are especially unlikely to grow (Coad & Karlsson, 2022).

Relevant here is the commendable design of the Dutch “Growth Accelerator Programme” (OECD, 2013, Chap. 7), a sophisticated program for training and supporting firms which was heavily subsidized by public funds, although joining the program was not entirely costless. Participants were required to commit to paying a matching contribution (€75,000 over a five-year period), which would only be a rational choice for entrepreneurs who have genuine growth aspirations. If the program had been free, then it might have been taken up by curious firms with no serious growth ambitions.

HGE policy could potentially be set up to allow firms to self-select to buy a growth option or a derivative such that they would only benefit if they grew, and if they do not grow they will have the costs but not the benefits. This way, firms can manipulate their incentive structure (in terms of the balance between upside gains and downside losses) to find themselves in a fast-track environment. For example, firms could be able to self-select into a program whereby they pay reduced employment tax on their next five hires, but there is a fixed cost involved (payable mainly at the end of the period), such that firms that select into this program but do not grow will pay a fixed cost but have no benefits.Footnote 14 Another idea could be a loan to potential HGEs that no longer needs to be repaid if the firm actually demonstrates genuine job creation. Therefore, firms will use their private information to self-select into a regime of enhanced incentives, which would only make sense for firms that are convinced of their growth potential.

4.4 The Need for Coordinated Policy

There has been a dramatic growth of SME policy and entrepreneurship policy in the United Kingdom, European Union, and elsewhere since the onset of the Thatcher-Reagan neoliberal turn.Footnote 15 The sudden appearance of thousands of entrepreneurship support programs has taken place in the context of an uncoordinated proliferation that has largely escaped evaluation. Nevertheless, Storey (2006), Shane (2009), and Lundström et al. (2014) document the uncoordinated nature of the expenditure from many different government departments, and the lack of awareness (by the public, and even among experts) of the sheer scale of government support for SMEs and entrepreneurs.

There is therefore a need for synergies and sometimes fewer HGE support programs, which should be coordinated across government departments and across the various levels of aggregation (local, regional, national), with these programs having explicit goals (job creation, creation of tax revenue, innovation, unemployment reduction, rural development, etc.), and also rigorous evaluations to see if the initiatives meet their stated goals.

Notes

- 1.

For example, firm growth can be defined in terms of absolute growth (total amount) vs relative growth (proportional rate of growth), employment growth vs sales growth, top 1% or top 5% or a time-varying proportion of firms with growth above a certain threshold (e.g., 20% growth threshold), growth measured over different timescales (e.g., 1- or 3- or 5-year growth periods), whether or not to include micro firms in the relevant sample, or whether to define high-growth entrepreneurs in terms of billionaires only.

- 2.

Dvouletý et al. (2021) review the evidence on grants for E.U. SMEs, and observe that grants are generally accompanied by improvements in survival, employment, tangible or fixed asset stocks, and sales, while the evidence regarding productivity is mixed.

- 3.

For example, older firms with previous application experience and better political connections might be able to prepare better grant applications.

- 4.

Regarding the self-selection hurdle, financial costs are probably preferable to time costs of bureaucracy, because high-potential entrepreneurs can be expected to have higher opportunity costs of time than low-potential entrepreneurs.

- 5.

An example would be the LEAD program: “individuals had to commit themselves to 2 days a month for 10 months. Following a series of interviews, 65 SMEs were selected to take part in the program on the understanding that nonparticipation would result in a £15,000 forfeit” (Roper & Hart, 2013, p. 20).

- 6.

No-compete agreements, also known as covenants not to compete, refer here to clauses in employment contracts that firms use to prevent individuals from working for a competitor, with the purpose of protecting their trade secrets, and guarding against knowledge spillovers to rivals.

- 7.

California is even known to invalidate no-compete agreements in employment contracts that explicitly designate the law of another state (Gilson, 1999, p. 608).

- 8.

Evidence on the success of EIF’s venture capital operations is presented by Pavlova and Signore (2021): Startups supported by the EIF experience higher IPO and M&A rates compared to similar, non-VC-backed firms. Moreover, they experienced a doubling of their patenting rate, compared to counterfactuals, likely due to the mitigation of financial obstacles to invest in R&D. Pavlova and Signore (2019) also document that startups supported by the EIF experience faster growth (in terms of assets) compared to non-VC-backed firms. This leads to higher capitalization levels, higher revenues, and higher job creation in the first 5 years following the VC investment.

- 9.

For the list of EIF’s partnership with leading national institutions see Country and sector-specific initiatives (Funds-of Funds and Guarantee Debt funds) at eif.org.

- 10.

- 11.

Europe now counts 52 venture-backed high-tech unicorns and 28 of them are supported by the EIF. This year, 17 were born and 34 raised more than €6 billion in total (EIF, 2021)

- 12.

This touches upon another important point: “policy liberalization as a long-term goal” (Elert et al., 2017, p. 5). The goal is not for policy to stay forever, but to pull out once the market failures are overcome and the activities are set up and sustained by market forces.

- 13.

The initiative was known as Prêt Industrie du Futur – Technologies et usages du futur. See for example, OECD (2018, p. 244).

- 14.

Perhaps the fixed cost could take the form of compulsory training using an online asynchronous education program set up to develop some relevant entrepreneurial skills. Another possibility could be that training or mentoring is billed 12 months later, but the bill is waived if the firm has actually hired or started exporting. In a similar spirit, perhaps personalized business advice is available but not free; instead it is only available after completion of a relevant online learning module.

- 15.

“The last four decades have seen a considerable increase in the scale and diversity of such policies across developed countries. An early developer, by EU standards, was the UK although, even here, SMEP [SME policy] during the 1970s comprised a mere handful of programs, and EP [Entrepreneurship policy] was nonexistent. Yet within three decades, the UK had more than a thousand such programs” (Lundström et al., 2014, p. 942).

References

Acs, Z., Åstebro, T., Audretsch, D., & Robinson, D. T. (2016). Public policy to promote entrepreneurship: A call to arms. Small Business Economics, 47(1), 35–51.

Akcigit, U., Grigsby J., Nicholas T., & Stantcheva S. (2022). Taxation and innovation in the 20th century. Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Arauzo-Carod, J. M., Segarra-Blasco, A., & Teruel, M. (2018). The role of science and technology parks as firm growth boosters: An empirical analysis in Catalonia. Regional Studies, 52(5), 645–658.

Åstebro, T., & Tåg, J. (2017). Gross, net, and new job creation by entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 8, 64–70.

Audretsch, D., Colombelli, A., Grilli, L., Minola, T., & Rasmussen, E. (2020). Innovative start-ups and policy initiatives. Research Policy, 49(10), 104027.

Autio, E., & Rannikko, H. (2016). Retaining winners: Can policy boost high-growth entrepreneurship? Research Policy, 45, 42–55.

Avnimelech, G., & Teubal, M. (2006). Creating venture capital industries that co-evolve with high tech: Insights from an extended industry life cycle perspective of the Israeli experience. Research Policy, 35, 1477–1498.

Avnimelech, G., Rosiello, A., & Teubal, M. (2010). Evolutionary interpretation of venture capital policy in Israel, Germany, UK and Scotland. Science and Public Policy, 37(2), 101–112.

Barrot, J. N., & Nanda, R. (2020). The employment effects of faster payment: Evidence from the federal quickpay reform. Journal of Finance, 75(6), 3139–3173.

Benedetti Fasil, C., Domnick, C., del Rio, J.-C., Fákó, P., Flachenecker, F., Gavigan, J. P., Janiri, M. L., Stamenov, B., & Testa, G. (2021). High growth enterprises in the COVID-19 crisis context demographics, environmental innovations, digitalization, finance and policy measures. EUR 30686 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2021, ISBN 978-92-76-37269-1. https://doi.org/10.2760/63402, JRC124469. Retrieved from https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/a2be487d-b202-11eb-8aca-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

Biancalani, F., Czarnitzki, D., & Riccaboni, M. (2021). The Italian start up act: A microeconometric program evaluation. Small Business Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00468-7

Bloom, N., & Van Reenen, J. (2010). Why do management practices differ across firms and countries? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(1), 203–224.

Bloom, N., Genakos, C., Sadun, R., & Van Reenen, J. (2012). Management practices across firms and countries. Academy of Management Perspectives, 26(1), 12–33.

Bloom, N., Van Reenen, J., & Williams, H. (2019). A toolkit of policies to promote innovation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(3), 163–184.

Bornhäll, A., Daunfeldt, S. O., & Rudholm, N. (2015). Sleeping gazelles: The unseen job creators? In A. C. Corbett, J. Katz, & A. McKelvie (Eds.), Entrepreneurial growth: Individual, firm, and region. Advances in entrepreneurship, firm emergence, and growth (Vol. 17, pp. 161–185). Emerald Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1074-754020150000017013

Borrás, S., & Edquist, C. (2013). The choice of innovation policy instruments. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 80(8), 1513–1522.

Bradley, S. W., Kim, P. H., Klein, P. G., McMullen, J. S., & Wennberg, K. (2021). Policy for innovative entrepreneurship: Institutions, interventions, and societal challenges. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 15, 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1395

Branstetter, L., Lima, F., Taylor, L. J., & Venâncio, A. (2014). Do entry regulations deter entrepreneurship and job creation? Evidence from recent reforms in Portugal. Economic Journal, 124(577), 805–832.

Bravo-Biosca, A. (2016). Firm growth dynamics across countries: Evidence from a new database. NESTA Working Paper 16/03, NESTA.

Bravo-Biosca, A., Menon, C., & Criscuolo, C. (2013). What drives the dynamics of business growth? OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers 1.

Brown, R., & Mawson, S. (2013). Trigger points and high-growth firms. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 20(2), 279–295.

Brown, R., & Mawson, S. (2016). Targeted support for high growth firms: Theoretical constraints, unintended consequences and future policy challenges. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 34(5), 816–836.

Brown, J. R., Martinsson, G., & Petersen, B. C. (2017). What promotes R&D? Comparative evidence from around the world. Research Policy, 46(2), 447–462.

Cai, J., & Szeidl, A. (2018). Interfirm relationships and business performance. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(3), 1229–1282.

Caliendo, M., Künn, S., & Weissenberger, M. (2020). Catching up or lagging behind? The long-term business and innovation potential of subsidized start-ups out of unemployment. Research Policy, 49(10), 104053.

Coad, A., Daunfeldt, S. O., & Halvarsson, D. (2018). Bursting into life: Firm growth and growth persistence by age. Small Business Economics, 50(1), 55–75.

Coad, A., Domnick, C., Flachenecker, F., Harasztosi, P., Janiri, M. L., Pal, R., & Teruel, M. (2021). Capacity constraints as a trigger for high growth. Small Business Economics.

Coad, A., Frankish, J. S., & Storey, D. J. (2020). Too fast to live? Effects of growth on survival across the growth distribution. Journal of Small Business Management, 58(3), 544–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2019.1662265

Coad, A., & Karlsson, J. (2022). A field guide for gazelle hunters: Small, old firms are unlikely to become high-growth firms. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 17, e00286.

Conti, A., & Roche, M. P. (2021). Lowering the bar? External conditions, opportunity costs, and high-tech start-up outcomes. Organization Science. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2020.1411

Corlett, A. (2018). Entrepreneurs’ relief has cost £22 billion over the past 10 years. Was it worth it?’. Resolution Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/comment/entrepreneurs-relief-has-cost-22-billion-over-the-past-10-years-was-it-worth-it/

Cruz, M., Baghdadi, L., & Arouri, H. (2021). High growth firms and trade linkages: Imports do matter. Small Business Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00538-w

Daunfeldt, S. O., Elert, N., & Johansson, D. (2016). Are high-growth firms overrepresented in high-tech industries? Industrial and Corporate Change, 25(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtv035

De Meza, D. (2002). Overlending? Economic Journal, 112(477), F17–F31.

Duruflé, G., Hellmann, T. F., & Wilson, K. E. (2017). From start-up to scale-up: Examining public policies for the financing of high-growth ventures. Bruegel Working Paper, No. 2017/04. Bruegel.

Dvouletý, O., Srhoj, S., & Pantea, S. (2021). Public SME Grants and firm performance in European Union: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Small Business Economics, 57(1), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00306-x

EIB. (2019). EIB Venture Debt as Growth Capital. Retrieved from https://www.eib.org/attachments/general/events/eib-venture-debt-oct-19.pdf

EIB. (2021). European Investment Bank Activity Report 2020. Retrieved from https://www.eib.org/en/publications/activity-report-2020

EIF. (2021). EIF Annual Report 2020. Retrieved from https://www.eif.org/news_centre/publications/eif-annual-report-2020.htm

Elert, N., Henrekson, M., & Stenkula, M. (2017). Institutional reform for innovation and entrepreneurship: An agenda for Europe. Springer Nature.

Fallick, B., Fleischman, C. A., & Rebitzer, J. B. (2006). Job-hopping in Silicon Valley: Some evidence concerning the microfoundations of a high-technology cluster. Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(3), 472–481.

Ferrando, A., & Lekpek, S. (2018). Access to finance and innovative activity of EU firms: A cluster analysis (no. 2018/02). EIB Working Papers.

Ferrando, A., Pal, R., and Durante, E. (2019). Financing and obstacles for high growth enterprises: The European case (no. 2019/03). EIB Working Papers.

Flachenecker, F., Gavigan, J. P., Goenaga, X., Pasi, G., Preziosi, N., Stamenov, B., & Testa, G. (2020). High growth enterprises: Demographics, financing & policy measures. JRC technical report. Joint Research Centre. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/publication/high-growth-enterprises-demographics-finance-policy-measures

Friesenbichler, K., & Hölzl, W. (2020). High-growth firm shares in Austrian regions: The role of economic structures. Regional Studies, 54(11), 1585–1595.

Garicano, L., Lelarge, C., & Van Reenen, J. (2016). Firm size distortions and the productivity distribution: Evidence from France. American Economic Review, 106(11), 3439–3479.

Gilson, R. (1999). The legal infrastructure of high technology industrial districts: Silicon Valley, route 128, and covenants not to compete. New York University Law Review, 74(3), 575–629.

Gilson, R. J. (2003). Engineering a venture capital market: Lessons from the American experience. Stanford Law Review, 55(4), 1067–1103.

Gompers, P., Kovner, A., Lerner, J., & Scharfstein, D. (2010). Performance persistence in entrepreneurship. Journal of Financial Economics, 96(1), 18–32.

González-Uribe, J., & Reyes, S. (2021). Identifying and boosting “Gazelles”: Evidence from business accelerators. Journal of Financial Economics, 139(1), 260–287.

Gottschalk, S., Greene, F. J., & Müller, B. (2017). The impact of habitual entrepreneurial experience on new firm closure outcomes. Small Business Economics, 48(2), 303–321.

Grover Goswami, A., Medvedev, D., & Olafsen, E. (2019). High-growth firms: Facts, fiction, and policy options for emerging economies. World Bank.

Hallak, I., & Harasztosi, P. (2019). Job creation in Europe: A firm-level analysis. European Commission. JRC Science for Policy Report.

Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R. S., & Miranda, J. (2013). Who creates jobs? Small versus large versus young. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(2), 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00288

Henrekson, M., & Johansson, D. (2010). Gazelles as job creators: A survey and interpretation of the evidence. Small Business Economics, 35, 227–244.

Henrekson, M., & Sanandaji, T. (2014). Small business activity does not measure entrepreneurship. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(5), 1760–1765.

Hvide, H. K., & Jones, B. F. (2018). University innovation and the professor’s privilege. American Economic Review, 108(7), 1860–1898.

Klingebiel, R., & Adner, R. (2015). Real options logic revisited: The performance effects of alternative resource allocation regimes. Academy of Management Journal, 58(1), 221–241.

Kuhn, J. M., & Teodorescu, M. H. (2021). The track one pilot program: Who benefits from prioritized patent examination? Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 15(2), 185–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1387

Link, A. N., & Scott, J. T. (2010). Government as entrepreneur: Evaluating the commercialization success of SBIR projects. Research Policy, 39(5), 589–601.

Lukeš, M., Longo, M. C., & Zouhar, J. (2019). Do business incubators really enhance entrepreneurial growth? Evidence from a large sample of innovative Italian start-ups. Technovation, 82, 25–34.

Lundström, A., Vikström, P., Fink, M., Meuleman, M., Glodek, P., Storey, D. J., & Kroksgard, A. (2014). Measuring the costs and coverage of SME and entrepreneurship policy: A pioneering study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(4), 941–957.

Mason, C., & Brown, R. (2013). Creating good public policy to support high-growth firms. Small Business Economics, 40(2), 211–225.

Mazzucato, M. (2011). The entrepreneurial state. DEMOS.

McKenzie, D. (2017). Identifying and spurring high-growth entrepreneurship: Experimental evidence from a business plan competition. American Economic Review, 107(8), 2278–2307.

Mitchell, J., Testa, G., Sanchez Martinez, M., Cunningham, P. N., & Szkuta, K. (2020). Tax incentives for R&D: Supporting innovative scale-ups? Research Evaluation, 29(2), 121–134.

Mukherjee, A., Singh, M., & Zaldokas, A. (2017). Do corporate taxes hinder innovation? Journal of Financial Economics, 124(1), 195–221.

Munch, J., & Schaur, G. (2018). The effect of export promotion on firm-level performance. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 10(1), 357–387.

Nielsen, K., & Sarasvathy, S. D. (2016). A market for lemons in serial entrepreneurship? Exploring type I and type II errors in the restart decision. Academy of Management Discoveries, 2(3), 247–271.

Nightingale, P. (2015). Schumpeter’s theological roots? Harnack and the origins of creative destruction. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 25(1), 69–75.

OECD. (2013, March). An international benchmarking analysis of public Programmes for high-growth firms. Final report prepared by the OECD Local Economic and Employment Development Programme in collaboration with the Danish Business Authority.

OECD. (2018). OECD economic surveys: Ireland 2018. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-irl-2018-en

OECD. (2019). OECD economic surveys: Japan 2019. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/fd63f374-en

Pavlova, E., & Signore, S. (2019). The European venture capital landscape: An EIF perspective. Volume V: The economic impact of VC investments supported by the EIF. EIF working paper 2019/55.

Pavlova, E., & Signore, S. (2021). The European venture capital landscape: An EIF perspective. Volume VI: The impact of VC on the exit and innovation outcomes of EIF-backed start-ups. EIF Working Paper 2021/70.

Pena, I. (2004). Business incubation centers and new firm growth in the Basque Country. Small Business Economics, 22, 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SBEJ.0000022221.03667.82

Penrose, E. T. (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm. Basil Blackwell.

Reypens, C., Delanote, J., & Ruckert, D. (2020). From starting to scaling: How to foster startup growth in Europe. European Investment Bank.https://doi.org/10.2867/42527

Rocha, V., Carneiro, A., & Varum, C. A. (2015). Serial entrepreneurship, learning by doing and self-selection. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 40, 91–106.

Roper, S., & Hart, M. (2013). Supporting sustained growth among SMEs–policy models and guidelines. ERC White Paper, 7, 1–68.

Rostamkalaei, A., & Freel, M. (2016). The cost of growth: Small firms and the pricing of bank loans. Small Business Economics, 46(2), 255–272.

Shane, S. (2009). Why encouraging more people to become entrepreneurs is bad public policy. Small Business Economics, 33, 141–149.

Sincu, G. (2017, May 30). Romania: Tax incentives for companies performing research and development activities. International Tax Review. Retrieved from https://www.internationaltaxreview.com/article/b1f7n76m3z099b/romania-tax-incentives-for-companies-performing-research-and-development-activities

Sine, W. D., & David, R. (2003). Environmental jolts, institutional change, and the creation of entrepreneurial opportunity in the U.S. electric power industry. Research Policy, 32(2), 185–207.

Smallbone, D., Baldock, R., & Burgess, S. (2002). Targeted support for high-growth start-ups: Some policy issues. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 20(2), 195–209.

Sorenson, O., Assenova, V., Li, G. C., Boada, J., & Fleming, L. (2016). Expand innovation finance via crowdfunding. Science, 354(6319), 1526–1528.

Srhoj, S., Vitezic, V., & Wagner, J. (2020). Export boosting policies and firm behaviour: Review of empirical evidence around the world. In MPRA paper 104330. University Library of Munich.

Stam, E., & Bosma, N. (2015). Local policies for high-growth firms. In D. B. Audretsch, A. N. Link, & M. L. Walshok (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of local competitiveness (pp. 286–305). Oxford University Press.

Storey, D. J. (1994). Understanding the small business sector. Routledge.

Storey, D. J. (2006). Evaluating SME policies and programmes: Technical and political dimensions. In M. Casson, B. Yeung, A. Basu, & N. Wadeson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of entrepreneurship (pp. 248–278). Oxford University Press.

Teruel, M., Coad, A., Domnick, C., Flachenecker, F., Harasztozi, P., Janiria, M.L., & Pal, R. (2021). The birth of new HGEs: Internationalization through new digital technologies. Journal of Technological Transfer.

Testa, G., Szkuta, K., & Cunningham, P. N. (2019). Improving access to finance for young innovative enterprises with growth potential: Evidence of the impact of R&D grant schemes on firms’ outputs. Research Evaluation. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvz016

The New York Times. (2019, November 8). The billionaires are getting nervous. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/08/opinion/sunday/bill-gates-warren-tax.html

Veugelers, R., Ferrando, A., Lekpek, S., & Weiss, C. T. (2018). Young SMEs: Driving innovation in Europe? (No. 2018/07). EIB Working Papers.

Zhou, H., & van der Zwan, P. (2019). Is there a risk of growing fast? The relationship between organic employment growth and firm exit. Industrial and Corporate Change, 28(5), 1297–1320.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Sofia Amaral-Garcia, Peter Bauer, Andrea Crisanti, Clemens Domnick, Helmut Kraemer-Eis, Pavlova Elitsa, Debora Revoltella, Sebastian Schich, and Wouter van der Wielen for many helpful discussions and comments. We are also grateful to Karl Wennberg and Christian Sandström (the editors) and an anonymous reviewer for helpful feedback. Any remaining errors are ours alone. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Investment Bank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Coad, A., Harasztosi, P., Pál, R., Teruel, M. (2022). Policy Instruments for High-Growth Enterprises. In: Wennberg, K., Sandström, C. (eds) Questioning the Entrepreneurial State. International Studies in Entrepreneurship, vol 53. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94273-1_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94273-1_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-94272-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-94273-1

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)