Abstract

This paper investigates the role of 3D modelling in enhancing our understanding of the spatial arrangement and representational character of a room in a 17th century Dutch home. The case study presented here is the entrance hall (“voorhuis” in Dutch) of the house of Pieter de Graeff and Jacoba Bicker located at Herengracht 573 in Amsterdam. This research draws upon a heterogenous dataset which includes the surviving architecture, the probate inventory of De Graeff’s properties that was drawn up after his death, and the almanacs in which he recorded some of the construction works in the house. This paper shows how the “materialization” of the inventoried objects in a 3D model suggests otherwise unnoticeable intentions and visual cues underlying their disposition within the room. In addition, this approach offers a non-intrusive and non-destructive way of visualizing past building phases and a room’s forgotten function which prompts a more dialogical engagement with architectural heritage in comparison to permanent physical reconstructions.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

In the last decades, considerations and reflections from architects, sociologists, and philosophers have expanded our perception of the deeply layered meaning of the house across different times and cultures. A house is not just a construction that responds to the practical necessities of providing shelter and protection, but also a symbolic space designed to reflect, express and reinforce socio-cultural norms and values (Rapoport 1969; Bourdieu 1977, 1979; De Mare 1993, 2003; Heldon 2004). The house has therefore been seen as a proxy to understand the workings of a society at large (Kent 1990). As such, the analysis of the degrees of its architectural complexity has been used to decode the underlying rules of social behaviour which overwrite the purely functional and strictly hierarchical principles of construction (Hanson and Hillier 1982; Hillier and Hanson 1984; Hanson 2003). Numerous studies have investigated the symbolic function of the house as a carrier of meanings and messages, such as the display of the owner’s wealth and status (see e.g. Hanson and Hillier 1982; Jameson 1990a, 1990b; Fock 1999, 2001; Hales 2003; Purves 2010). According to Goffman’s interpretation of social interaction as a dramatic performance, the house is one of the settings in which human action is played out (Goffman 1956). In his view, its layout, furniture and other items in the rooms constitute the “stage props” which shape the scenic aspect of this performance (Goffman 1956, 13–4). Thus, the house can be read as a combination of “front stage” and “backstage” areas which create the prerequisites for what Goffman defines as “impression management”: in front stage areas the performers disseminate information to guide and influence the impression they want the viewer to hold about them, while in backstage areas, which are hidden from the intended audience, the performers “behave out of character” and have time to prepare the performance (Goffman 1956, 70).

Loughman and Montias applied Goffman’s dramaturgical model to 17th century Dutch interiors and showed a non-casual disposition of works of art in the houses of that period. From their analysis of a selection of six probate inventoriesFootnote 1 from upper middle class houses in Amsterdam and Dordrecht, they recognized an increasing distinction as the century progressesFootnote 2 between spaces to receive guests (the “front stage”), where the most expensive items were placed, and rooms with a more private character (the “backstage”), where paintings with moralizing subjects were preferred due to their pedagogical value for the younger generations (Loughman and Montias 2000, 71–104).Footnote 3 This change is also observable in the placement of furniture. For example, beds (a typical feature of backstage areas, as noted by Goffman 1956, 73–4) are present in some of the reception rooms until the last quarter of the century. After that they were often replaced by a couch with mattress and pillows following the French fashion (Fock 1999, 41–2).

As “one of the principal venues for front stage activities” (Loughman and Montias 2000, 72), the entrance hall had a marked representational character (Sluijter 2001; Fock 2007a). For this reason, this research focuses on this room to investigate the role of 3D modelling in exploring the choices made by the owner of the house regarding the disposition of furniture and objects. Specifically, this case study is the entrance hall (called “voorhuis” or “voorhuys” in Dutch) of the Amsterdam canal house on the Herengracht 573 at the time when it belonged to Pieter de Graeff (1638–1707), who lived there with his wife Jacoba Bicker (1640–1695) (Fig. 1) and their five children Agneta (1663–1725), Joannes (1664–1666), Cornelia (1669–1688), Cornelis (1671–1719) and Jan (1673–1714). The aim of this work is to investigate to what extent the positioning of the objects in this room was purposely chosen and, if this is the case, which messages they meant to convey to the visitors entering the house.

One of the main sources for this research is the probate inventory that was drawn up after De Graeff’s death in 1707. As Beaudry pointed out, archaeologists and historians analysing this type of documents almost instinctively “materialize” them when they “read out of the text the physicality of objects—words become things—and immediately begin to furnish in their minds a home (…)” (Beaudry 2015, 7). However, this process remains usually confined in the researcher’s mind and lacks the possibility to visualize and test the formulated hypotheses in a real-world measurement environment. This paper aims to demonstrate how by “materializing” the household furnishings and objects with the help of a 3D model it is possible not only to make this mental picture explicit, but also to gain new insight in the use of space and disposition of objects in the room. In this way, the 3D environment is used as an interpretative and exploratory tool which helps in exploring agency in domestic interiors, simulating alternative hypotheses and actively contributing to generating new knowledge (Piccoli 2018, 67–83).

2 At Home at Herengracht 573

The De Graeff’s household was part of the Amsterdam elite, as both husband and wife stemmed from powerful and wealthy families who dominated the political scene at that time. Pieter de Graeff was the son of Cornelis de Graeff (Amsterdam Burgomaster several times) and Catharina Hooft (also descendant from an important family). Jacoba Bicker was the daughter of Jan Bicker (a wealthy merchant and political figure) and Agneta de Graeff of Polsbroek (Pieter’s aunt). One of Jacoba’s sisters, Wendela, married the statesman Johan de Witt, who was a close friend of Pieter de Graeff. De Graeff became a member of the Amsterdam city council (“Vroedschap”) in 1662, one of the chief administrators (“bewindhebber”) of the Amsterdam chamber of the Dutch East India Company in 1664, and alderman (“schepen”) in 1668.Footnote 4 As a supporter of Johan de Witt, he was then dismissed by the stadtholder William III of Orange during the eventful year 1672 together with others of his family members with Republican sympathies. Over the years, he inherited numerous possessions from his parents and relatives including the estates of Zuid-Polsbroek (south-east of Utrecht) and Purmerland and Ilpendam (north of Amsterdam), as well as expensive paintings such as a portrait of his uncle Andries made by Rembrandt. Much of his profits came from his possessions of stocks in his lands (Zaandvliet 2006, 94) and from renting out his numerous properties.Footnote 5

The first stone of their house at Herengracht 573 was laid out on the 17th April 1665 and the family moved in one year later.Footnote 6 This house was chosen as the case study for this research due to the availability of a heterogeneous dataset which allows us to combine information from different sources. Beside a detailed probate inventory that was drawn after De Graeff’s death in 1707 which lists most of the household objects room by room,Footnote 7 we can extract additional information about the house interior from the almanacs (“Dagelijkse notities”) preserved at the Amsterdam City Archives that he kept for about forty years (Fig. 2).Footnote 8 In these accounts, De Graeff recorded the works in the house, including the names of artists and craftsmen from whom he commissioned them.Footnote 9 In addition to this archival documentation, we can also rely on plans and drawings kept at the Monuments and Archaeology office of the City of Amsterdam and on the spatial information provided by the building itself, which still survives and hosted the Museum of Bags and Purses until 2020. Over the course of the generations, the building underwent numerous changes both in the interior and on the façade, of which the earliest and most substantial were made by Pieter de Graeff’s grandchild, Gerrit, in the first half of the 18th century.

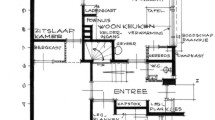

An 18th century drawing by Caspar Philips and some historical photos show that the entrance was originally located in the central bay on the bel-etage and was reached by a flight of steps with a landing. These steps were dismantled in 1868 when a window was created in place of the main entrance. This modification therefore turned the voorhuis into a sort of anteroom giving access to two larger side rooms (Fig. 3). The fact that this space’s original function is completely unrecognizable nowadays made it an interesting case study to evaluate the role of 3D modelling in investigating its past appearance. In the next section I will present the sources that are available to reach this goal and then I will discuss the insight provided by the creation of the 3D reconstruction in more detail.

3 The Entrance Hall: Sources for a Reconstruction Hypothesis

3.1 Almanacs, Inventory, and Physical Remains

Pieter de Graeff’s almanacs, his probate inventory and the physical remains of the building allow us to integrate the fragmentary information that each of these sources provide to obtain a more complete image of the entrance hall at the time in which the De Graeff family lived in the house. From the almanacs, we know that the construction works on the voorhuis started in October 1666 when the floor was laid out. De Graeff recorded in his notes that he used 20.5 “Swedish red stones” of 2 voetenFootnote 10 (56.6 cm) as bands in the floor and that he bought 6 white marble thresholds, 5 of which measured 3 voeten by 10 duim (84.9 by 25.7 cm) and a larger one of 4.5 voeten by 14 duim (ca. 127.3 by 36 cm) for the portal.Footnote 11 The Swedish red tiles that De Graeff mentions are to be identified as made of the red Öland stone which was imported from the island of Öland just off the southeast coast of Sweden.Footnote 12 From another passage of the almanacs, we know that the remaining tiles were made of white Italian (Carrara) marble.Footnote 13 Together with the red Öland tiles, the white marble offered an aesthetically pleasing combination which had been already used in the recently constructed Amsterdam Town Hall. In fact, this imposing building served as the reference point for architectural experimentation in the elite houses constructed in the same period or shortly after.Footnote 14

For several years there are no further mentions of works in the voorhuis until 1682 when De Graeff records that he commissioned Paulus de Fouchier to paint its coffered ceiling together with the ceiling of the adjacent room (“Zydelkamer”) and staircase.Footnote 15 The two latter ceilings are still preserved in their original locations and depict the personification of Amsterdam surrounded by the four continents,Footnote 16 and cupids respectively. Unfortunately the almanac’s entry does not contain information about the subjects depicted on the ceiling of the voorhuis, which nowadays still maintains the coffered construction but has been painted over in white and dark red. Other entries from the almanacs indicate that it had some gilded decorations. In fact, the painter Jacob Smit, who applied gold to the ceiling of the zydelkamer a few months earlier,Footnote 17 was called again to work in the voorhuis in November 1683.Footnote 18 Finally, the voorhuis is mentioned in 1691 when De Graeff notes that he commissioned the sketches for four oval-topped and six upper grisailles from the painter and draughtsman Romeyn de Hooghe.Footnote 19 The four larger ones had allegorical subjects related to edifying properties, namely the Education (“Educatie”), the Dedication (“Applicatie”), the Probity (“Probiteijt”) and the Piety (“Pieteijt”), while the themes of the upper ones are not mentioned. This type of wall decorations, for which Gerard de Lairesse is particularly known, was in fashion in palaces, city halls and upper-class private houses in the second half of the 17th century (van Eikema Hommes and Bakker 2008, 223). In this case, neither the original grisailles nor the preparatory sketches have survived, similarly to most of de Hooghe’s painting production. The few still preserved include the grisailles that he painted for the city hall of Enkhuizen and for the portal of the new city hall in Alkmaar, which give us an idea of his drawing style.Footnote 20

While the almanacs record the diachronic development of the works on the voorhuis, the probate inventory captures the content of this room after De Graeff’s death in 1707 (Fig. 2, left). The first items in the list are two paper candleholders (“Twee papiere blakers”), the appearance of which is still uncertain due to the lack of evidence of similar objects. In a passage of his almanacs, De Graeff mentions four gilded candle holders that his wife made with paper as a gift for an acquaintance.Footnote 21 This note gives us the closest reference to the items in the inventory, but still leaves some open questions as to how to model them correctly. The following items are two maps, which were common in the voorhuis (Loughman and Montias 2000, 59) and were usually chosen according to the specific interests or occupations of the owner.Footnote 22 De Graeff had one map of Zuid-Polsbroek (“Een kaart van Zuijd Polsbroek”), the family’s estate, and one of the City of Amsterdam (“Een d[it]o van Amsterdam”). The list continues with an oak table with a marble top (“Een eeken taaffel met een marmerblad”), a lint curtain “from Smyrna” (“Een Smirnase pluys gordijn”), a carved wooden bench (“Een gesneden bank”) and a marble table with a walnut foot (“Een marmore taaffel met een notebome voet”), and finally closes with two plaster portraits (“Twee pourtraicten van Pleysterwerk”). It must be noted that silver and golden objects are all grouped together towards the end of the inventory instead of being listed room by room. We therefore cannot exclude that some additional objects, for example silver lighting devices, were originally placed in the voorhuis. Moreover, the testament that De Graeff and his wife deposited in 1695 mentions paintings (“schilderijen”) (unspecified in subject and amount) in the voorhuis bequeathed to their eldest son Cornelis.Footnote 23 Although it cannot be confirmed with certainty at this moment, the fact that in their previous testament (dated 1688) there is no mention of paintings in the voorhuis may indicate that they refer to the above-mentioned grisailles and not to the presence of additional paintings that were not recorded in the inventory.Footnote 24 As far as the pieces of furniture mentioned in the inventory, there is no surviving example that can be identified as specifically belonging to this household. For this reason, the visual references for the creation of 3D models of the tables and the bench have been drawn from the types that were in fashion in the second half of the 17th century.Footnote 25 Figure 4 displays a part of the workflow to obtain the 3D models of the tables. The description of the curtain can possibly refer to Ottoman velvet, a textile that was much sought after at that time (Lessi 2000). Interestingly, the almanacs contain a reference to the ordering of a large cloth from Izmir: in December 1685, Jacoba Bicker sent a note to the wife of Captain Anthony Colomby asking her to bring them a large Turkish cloth of ca. 6 × 4 m.Footnote 26 Due to its dimensions, this cloth might have served as the curtain that we find back in the inventory, perhaps covering both the window and the entrance door.

For two items of the list, specifically the map of Zuid-Polsbroek and the two plaster portraits, the integration of the information derived from the almanacs allows us to provide some more specific visual comparisons. A large manuscript map of Zuid-Polsbroek, which was made in 1668 by the surveyor and draughtsman Johannes Leupenius by request of Pieter de Graeff, is kept at the Amsterdam City Archives (Fig. 5).Footnote 27 Two entries in the almanacs more than a decade later record the agreements between De Graeff and Leupenius to make copies of the map of Zuid-Polsbroek.Footnote 28 According to the information we can gather from the almanacs, it was indeed around the same time when new interventions were made on the voorhuis, namely the painting of the ceiling (see above). It is possible that a renewal of this room took place in this period, and that the item in the inventory therefore refers to one of these copies of the original map made in 1668 which was hung on the wall. Although it is not certain that this map corresponds to the one that is recorded in the inventory as hanging in De Graeff’s voorhuis, it certainly provides us with the closest comparison to the item listed there.

In the case of the two portraits, the identity of their subjects has not been recorded in the inventory. A hypothesis for their identification is here suggested based on information collected from other documents. The only mention of plaster portraits in the almanacs relates to the commission to an otherwise unknown Master Anthony of plaster casts from two bas-reliefs depicting De Graeff’s parents made by the famous sculptor Artus Quellinus (Fig. 6).Footnote 29 Although there is no mention of the purpose of this commission nor of the destination of these portraits, the inventory of Catharina Hooft, Pieter’s mother, gives us precise indications as to where they were hung. In fact, Quellinus’ bas-reliefs depicting her husband and herself were listed in the salon (“zaal”) of their house at the Herengracht 216,Footnote 30 while two plaster portraits of the couple were listed as being in their front room (“voorkamer”).Footnote 31 The latter are likely those that De Graeff mentions in his almanacs.Footnote 32 In this reconstruction I propose to identify the two plaster portraits mentioned in the inventory as being in fact the copies of those made by Quellinus. This suggestion is based on the hypothesis that De Graeff could have brought the two plaster portraits from his parents’ house after his mother died in September 1691 and hung them in this prominent location in his own. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that his inventory contains other paintings which were previously listed in his mother’s inventory.Footnote 33

3.2 Visual References for 17th Century Dutch Interiors

Despite the numerous and, at times, very precise pieces of information that the sources provide, some unknown elements remain. For example, we know the exact dimensions of the doors’ thresholds but nothing regarding the appearance of their frames, which were changed in the 18th century.Footnote 34 Moreover, as already noted, additional challenges arise from the fact that the short-written descriptions of the household properties are often difficult to translate into the corresponding object. Therefore, it is necessary to rely on comparisons to fill in these gaps. The 17th century Dutch house has become familiar to us because of our exposure to domestic scenes in contemporary genre paintings. However, a close comparison between paintings depicting interiors, the household possessions listed in probate inventories, and the domestic architecture of the period shows that such images should not be considered completely faithful renditions of contemporary interiors. As Fock demonstrated, luxury items that are often found in paintings, such as elaborate brass chandeliers, are in fact seldom found in inventories, while other objects that are recurrent in inventories (for example simple floor matting) are in turn systematically overlooked in paintings (Fock 1998). Moreover, the omnipresent black and white floor tiles were less common in reality than what paintings induce us to believe. In addition, some architectural features, such as the “enfilade” of rooms in Emanuel de Witte’s “interior with a woman at the virginal”, were not typical of the Dutch house of the period but represent a later introduction influenced by the French fashion (Fock 1998). In fact, painters aimed not for realistic representations, but for scenographic effects in their compositions and spatial settings and for the expression of their artistic skills when painting challenging subjects, such as light reflections and expensive fabrics (see Wijsenbeek-Olthuis 1996; Fock 1982, 1998; Muurling 2002). This type of source has been therefore considered with caution during the 3D reconstruction process.

In searching for more reliable sources for the appearance of upper-class interiors, we can turn to contemporary doll houses. These very detailed three-dimensional miniature houses were pastimes for upper class wives who assembled their collection of furniture and other household objects with great effort and expenditure over the years. As numerous studies have shown, these doll houses provide us with a reliable representation of contemporary upper-class interiors, albeit with a marked female domestic topography.Footnote 35 They present, in fact, a selective view focusing on the female presence and her ideal role in the domestic sphere in which the head of the house is almost completely absent. One example of this is the existence of a dedicated lying-in room for new mothers (“kraamkamer”) which was usually set up ad hoc for the occasion in one of the reception rooms and was not a permanent feature in houses of that period. One of the most famous doll houses is the one of Petronella Oortman (dated between ca. 1686 and 1710), now at the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum,Footnote 36 for which the painting by Jacob Apple provides contemporary evidence of its state around 1710.Footnote 37 Interestingly, the walls of its voorhuis are decorated with grisailles (see Fig. 7): an oval-topped one on each side of the longer walls and one smaller one on top of each door. This wall decoration is the closest visual comparison to the appearance of the voorhuis of Herengracht 573, as De Graeff describes it in his almanacs. For this reason, pictures of these grisailles have been used as texture images for the grisailles in the 3D reconstruction discussed here. Also, the wooden benches placed on each side of the doll house’s entrance hall provided the visual reference for the bench in the De Graeff’s voorhuis.

Petronella Oortman’s doll house (ca. 1686–1710), currently at the Rijksmuseum (BK-NM-1010), with the voorhuis occupying the central space. This room is decorated by grisailles on the walls and has a wooden bench on each side (see detail in the picture to the right) and it offers a contemporary visual reference for De Graeff’s voorhuis

Lastly, surviving examples of 17th century architecture provide evidence of the style and the materials in use at the time. The architectural style in fashion during the period when the house at the Herengracht was constructed is Dutch classicism, with architects Jacob van Campen, Pieter Post and Philips Vingboons as main exponents. Van Campen was one of the architects who introduced this style to the Netherlands, his inspiration coming from the ideal Vitruvian rules of proportions and orders in architecture interpreted by Renaissance architects such as Andrea Palladio and Vincenzo Scamozzi. Scamozzi’s treatise Idea dell’Architettura universale (Venice 1615) had an especially great impact on the development of Dutch classicism and was used as an actual construction manual.Footnote 38 Among the surviving evidence of this style, the most prominent is the already mentioned Town Hall in Dam Square which was designed by Van Campen in mid-17th century using Scamozzi’s Roman and Corinthian orders on the façade (Ottenheym 2007). As for domestic architecture, numerous double-width canal houses in Amsterdam were designed around the same period of De Graeff’s house according to Scamozzi’s principles. They include: the residence of Carel Gerards at Herengracht 386 (built in 1664–5) and the residence of Guillaume Belin la Garde at Herengracht 412 (1664), both designed by Philips Vingboons, as well as the Trippenhuis at Kloveniersburgwal 29, built by Philips’ younger brother Justus in 1660–2 under the commission of the two brothers Louis and Hendrick Trip.

Interestingly, there are elements that directly tie Scamozzi’s works with the De Graeff’s family: the Dutch translation of Scamozzi’s Book III on villas and palaces that was published by Dancker Danckerts in 1658 was dedicated to Pieter de Graeff’s father, who, Burgomaster of Amsterdam at the time, was one of the initiators of the construction of the new City Hall (Ottenheym 2007, 191). Moreover, as we can gather from his book auction catalogue,Footnote 39 Pieter himself owned a copy of the abbreviated version of Scamozzi’s Book VI, compiled by the master-mason Joost Vermaarsch (Fig. 8).Footnote 40 This edition in a compact quarto format was intended as a proper construction manual and was published in Leiden in 1664, incidentally the same year in which Pieter and his father bought the parcel on the Herengracht where the house was soon to be built. Notably, Vitruvius’ De Architectura also appears among the books in De Graeff’s catalogue.Footnote 41 Although the name of the architect who designed the house at Herengracht 573 is not known,Footnote 42 it is likely that it was built and decorated according to this style and relying on a workforce and artisans who were already involved in the construction of other buildings. For example, Artus Quellinus, the sculptor from whom De Graeff commissioned the plaster casts, also made the sculptures for the City Hall. In fact, it was Pieter’s father, who, together with the architect Jacob van Campen, was responsible for the choice of Quellinus for this important new project (Scholten 2010, 15). The appearance of the reconstructed interior is therefore in line with this architectural style and some of the elements are directly taken from surviving architecture of the period. For example, the door frames here are constructed of wood and painted over to look like marble. This was a common technique used most notably in the Amsterdam City Hall. This choice is also supported by the fact that De Graeff himself showed an interest in this faux marble effect: in August 1666, in the midst of his house’s construction works, he noted down the name of Alexander de Ruel (known also as Ruwel) as the painter who used this technique at somebody else’s house.Footnote 43

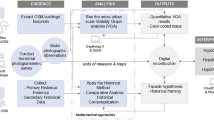

4 “Materializing” Household Objects in a 3D Digital Model

The following paragraphs describe the steps taken for the creation of a 3D visualization of the voorhuis and the insights that this process has generated. The preparatory stage for the 3D reconstruction of the voorhuis includes the broader analysis of the whole house, to retrace the original circulation routes within, and to identify from which door the notary and his clerk(s) would have entered. Building plans made in 1974 (see Fig. 3) were a useful starting point for better understanding its structure since they record some of the changes that the house underwent, especially doorways that have been walled up at a certain point in time. Several on-site inspections were carried out to double-check the plans and to start to correlate the rooms listed in the inventory with the corresponding rooms in the current spatial arrangement.Footnote 44 The plans made in 1974 were then digitized in AutoCAD, which made it easier to compare the changes made on different floors, and imported into the 3D modelling Open Source software Blender to re-assemble them into the building’s 3D frame (Fig. 9). Beside the doorways, part of the main staircase and the dismantled service stairs also needed to be reconstructed in their original location and dimensions. The 3D model allows the exploration of alternative possible reconstructions of both stairs to see how they would interact spatially and visually with the rest of the house.

This approach led to the reconstruction of the route that the notary and his clerks took when entering the voorhuis, namely from the door on the most narrow wall of this room.Footnote 45 This location offers the first anchor point to start placing the objects listed in the inventory. The other anchor point is the curtain, which is halfway down the list and undoubtedly covered the window on top of the main entrance door (and, as previously mentioned, possibly the door as well).Footnote 46 Several alternatives have been explored to find the most plausible disposition in order to fit the maps, the furniture pieces and the plaster portraits in the spaces left by the doorways, the window opening and the grisailles which occupied the walls. The results of this process are displayed in Fig. 10. By maintaining the order of the objects as mentioned in the inventory (thus assuming that it reflects their location within the room), we find out that the two tables that are listed a couple of objects apart (respectively the fourth and the seventh items in the inventory list, see Fig. 2) would have been positioned facing each other along the two longer sides of the room. This disposition gives a sense of symmetry to the ensemble, as was indeed in fashion at the time (Fock 2007a, 65). An empty space to the left of the main entrance would have provided enough room for the door shutter to open towards that direction, while on the other side the wooden bench would have accommodated visitors waiting to be received. Given their uncertain identification, the placing of the two candle holders remains ambiguous.

In addition, the scale model made it possible to experiment with various arrangements of the floor tiles to test which one would allow the laying out of 20.5 red tiles, the number that De Graeff recorded in his almanacs as being used in his voorhuis’ floor. The most likely pattern matching this number mirrors the structure of the coffered ceiling, as it is was in fashion in that period, and allows the most efficient laying down of tiles with minimum need of cutting both red stone and white marble tiles.Footnote 47

By placing the objects listed in the inventory back in their original location, this 3D model provides a qualitative method of assessing which objects visitors would have seen when entering the house. As seen in Fig. 10, after crossing the main entrance door they would have had in front of them the map of the family’s estate in Zuid-Polsbroek, the map of the beloved city of Amsterdam and the two portraits. Therefore, the visitor entering the house would have been immediately made aware of the household’s status and lineage, even more so if we take the identification of the plaster portraits with De Graeff’s parents as plausible. Moreover, the two tables opposite each other would have given a sense of symmetry to the room. This work has demonstrated that the “translation” of the textual information into a visual representation enables the detection of spatial correlations, prominence and strategic placements of objects, which were not evident from the textual sources alone.

5 Discussion

This paper explored the contribution of a 3D reconstruction to gain insight into the representational character of the entrance hall of De Graeff’s grand canal house. The making of this 3D model allowed re-introducing the spatial dimension into the list of objects recorded in De Graeff’s probate inventory. This process of “virtually materializing” the room and its furnishing has made it possible to suggest an otherwise unnoticeable visual hierarchy and symmetry within it. At the same time, by transferring the mental image of what this room would have looked like into a digital scale model, the creation process and the results are made explicit and verifiable. In this way, the 3D reconstruction has become both an interpretative and an expressive means of visualizationFootnote 48 which enables knowledge creation and sharing.Footnote 49 There is no doubt that this type of approach to visualizing past housing phases and lost room functions in historical buildings will be increasingly used in place of on-site physical reconstructions, which usually result in a more intrusive, permanent and often problematic intervention on a heritage site.Footnote 50

The research that was here discussed, driven by the creation of the 3D reconstruction, has shown the importance of collecting and integrating evidence from various sources. In fact, a great deal of information on the appearance of this room (most notably the presence of grisailles on the walls) would have been missed by looking at the inventory alone. The cross-referencing of this multidisciplinary dataset has created new links and relations among previously unconnected pieces of information. The creation process has therefore turned the 3D model into a virtual hub where these data are integrated and spatially visualized. However, the complex relation between the certain, the inferred and the hypothetical is inevitably simplified in the resulting visualization and hidden to the viewer if the latter is exposed only to the end result of this process. As such, challenges arise related to providing an effective knowledge management which guarantees an adequate and long-term access to the underlying data sources and a transparent assessment of the varying degrees of certainty in their identification.

Over the years, photo-realistic 3D visualizations of archaeological and historical sites have been increasingly seen as powerful non-transparent visualization modes which need to be accompanied by sufficient information to enable their evaluation. In fact, 3D reconstructions have been compared to the philological restoration of a fragmentary text (Frischer et al. 2002) and to the creation of an academic paper (Denard 2012) with a common underlying concept: instead of being presented only with the conclusions, the viewer should be able to access the sources and follow the entire reasoning and decision-making process behind the reconstruction. The London Charter for the computer-based visualization of cultural heritageFootnote 51 and the Seville Principles,Footnote 52 more specifically targeted at virtual archaeology, aimed to raise awareness on the need of quality standards in this field and proposed a set of principles that this kind of visualizations need to comply to. The degree to which the principles have been adopted in the past and current projects still vary greatly, and the development of more applied workflows is needed in order to demonstrate and evaluate possible ways to tackle the above-mentioned issues in practice.Footnote 53 A thorough documentation of the underlying data and reconstruction process is also key to enhance the chances of their long-term availability in the presently still uncertain future of 3D assets’ storage and preservation.

This research aims to approach the 3D modelling of the interiors in a documented and consistent way. To this end, the decision-making process and the sources for the reconstruction hypotheses are recorded in a system of related spread sheets and written reports which also keep track of possible alternative reconstructions and record the uncertainty value of the reconstruction hypotheses that are chosen to be represented. For example, two columns in the spreadsheet store a “confidence index”: namely a numerical value from 1 (closer to original) to 4 (uncertain) that expresses the degree of certainty for the identification of each object and their location. In this way, it is possible to differentiate between objects for which the location is certain, but their appearance is not (e.g. the curtain) and vice versa. Moreover, a column lists the object taken as comparison for each 3D model in the scene and another contains the explanation of the reasoning behind the choice.

These underlying pieces of information are being integrated into a prototype web-viewer designed as part of the NWO-funded project “Virtual Interiors as Interfaces for Big Historical Data Research Spatially enhanced publications of the creative industries of the Dutch Golden Age”, which the research presented here is part of.Footnote 54 As the web-viewer directly queries the information in the spreadsheet, this system makes it easy to update the visual references that have been used for representing the items in the room in case new evidence is available. The numerical values describing the uncertainty translate into a color-coded scheme (for the moment from green to red) which visualizes the various degrees of certainty and overlay them onto the reconstruction. As such, the web-viewer acts as a trustworthy interface and research environment for exploring these historical virtual reconstructions, their uncertainty values, alternative hypotheses, underlying data sources and related Linked Data in an interactive and customizable way. In doing so, it enables a more dialogical form of engagement with the proposed 3D reconstruction (Fig. 11).Footnote 55

A screenshot of the prototype web-viewer designed as part of the Virtual Interiors project (available at https://www.virtualinteriorsproject.nl/output/). The viewer allows the real-time exploration of the 3D reconstruction, of the decision-making process and of the complex web of underlying data sources (see Huurdeman and Piccoli 2021).

Notes

- 1.

Probate inventories recorded personal possessions upon the time of the owner’s death. Inventories could also be drawn up by a notary or his clerk(s) in other circumstances, such as when a marriage was stipulated or in case of bankruptcy. As highlighted in Schuurman (1980), they represent an important source to gain insight into personal possessions, wealth patterns and consumer culture although they are affected by biases and limitations (e.g. only middle and upper classes had their goods inventoried, while the lowest social classes are underrepresented, see Faber 1980).

- 2.

It must be noted that other studies have identified the distinction between front and back stage areas already in 16th century houses (Van Tussenbroek 2016a).

- 3.

- 4.

See Alphabetisch Register van de Naamen der Magistraatspersoonen van Amsterdam 1578–1768, III boek, VII deel, p. 207.

- 5.

Amsterdam City Archives, from now on: SAA (“Stadsarchief Amsterdam”), Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nrs. 186–226, passim. De Graeff ranked at nr. 44 in Zandvliet’s book on the 250 richest men in the Dutch Golden Age, with a capital of at least 600.000 guilders (Zaandvliet 2006, 93–7).

- 6.

On 29 April 1666, as recorded in De Graeff’s almanacs (SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 188 (1666)).

- 7.

SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Notarissen ter Standplaats Amsterdam (nr. 5075), inv. nr. 5001, fols. 425-493, notary Michiel Servaas (nr. 199), 8 March 1709 (the notary signed this inventory as “Michiel Servaas”, while his surname is spelled “Servaes” in the list of Amsterdam notaries in the archive nr. 5075). Silver and golden objects are not listed per room but are grouped under a heading of their own and accompanied by their weight (fols. 464–474); the same goes for materials such as tin, copper, iron (fol. 463).

- 8.

SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nrs. 186–226: From 1664 to 1707 (1700 is currently missing).

- 9.

Willemijn Fock provided the first overview of some passages from De Graeff’s almanacs, highlighting the importance of this unique source for investigating the owner’s personal choices in the house construction and decoration during the early modern period (Fock 2007b). Furthermore, the almanacs contain invaluable information to shed light on the commission of paintings: For example, on 22 July 1673, De Graeff’s records the payment to Gerard ter Borch of a copy of his brother Jacob’s portrait (SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 193 (1673)). One of the two identical portraits on oval-topped wooden panels is now at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (SK-A-3963), the other one at the Saint Louis Art Museum (see Korevaar and Tauber 2014).

- 10.

One “voet” (feet) corresponds to 28.3 cm and one “duim” (thumb) to 2.57 cm.

- 11.

SAA , Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 188 (1666), 11 October and 13 November. It is not clear whether all these thresholds were meant only for the voorhuis or also for the other rooms on this floor. If the former case were true, this would mean that the voorhuis had originally two doors on each side, which were then walled up to make space for the grisailles.

- 12.

Examples of this stone used in floors of 17th century houses are given in Koldeweij (2008) and Groeneveld (2010–2011).

- 13.

SAA Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 188 (1666), 6 July. For the international building materials trade in Amsterdam in that period, see Van Tussenbroek (2016b).

- 14.

See below, section “Visual references for 17th century Dutch interiors”. The first stone of the new City Hall was laid in 1648 and the construction lasted for several years. For the history of the city hall’s construction works, see Vlaardingerbroek (2011) (esp. pp. 123–9 for the materials) and Vlaardingerbroek (2019).

- 15.

SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 202 (1682), 10 and 12 August and 7 November; inv. nr. 204 (1684), 17 June.

- 16.

See https://rkd.nl/explore/images/70979 (last accessed August 2021).

- 17.

SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 203 (1683), 15 February. Cf. Fock (2007b, 9).

- 18.

SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 203 (1683), 4, 11 and 24 November. Smit will also work on the gilding of the stairs one year later (SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 204 (1684), 25 September and 25 October).

- 19.

SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 211 (1691), 21 August, 19 and 24 November. See also De Graeff’s travel journals where he mentions visiting de Hooghe in Haarlem on 30 July, 12 and 17 November and 21 December 1691 to talk about the making of these canvases (SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 184A, passim).

- 20.

- 21.

SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 210 (1690), 24 January.

- 22.

For example, two maps of the West India possessions were hung in the entrance hall of the “Bartolotti house” at Herengracht 170–172, a clear connection with the owner’s role as West India company director and Levant trader (Schama 1997 [1987], 313).

- 23.

SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 609 Portefeuille 2, nr. 7, fol. 15 v. (notary Gerrit Steeman, 31 January 1695).

- 24.

SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 609 Portefeuille 2, nr. 6’, unpaginated (notary Michiel Servaas, 28 May 1688).

- 25.

- 26.

SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 205 (1685), 6 December (“(…) van Smirna voor ons noch wil mede brenge een groot Turx kleet langh 9 ellen en breedt 6 ellen (…)”). One Amsterdam el corresponds to 68,8 cm.

- 27.

SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 454.

- 28.

SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 201 (1681), 31 October and inv. nr. 202 (1682), 15 June. The commission of this and of De Graeff’s other maps is discussed in Otten (1995).

- 29.

SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 190 (1670), 4 August and inv. nr. 191 (1671), 8 April; the original marble bas-reliefs made by Quellinus are kept at the Rijksmuseum (BK-KOG-1458-A and BK-KOG-1458-B).

- 30.

SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 605, Serie A 1-34, nr. 34, fol. 45 (notary Dirk van der Groe, 18 August 1692). The two bas-reliefs had gilt frames and were valued at 25 guilders. See also Scholten and Hoyle 2006, 115.

- 31.

SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 605, Serie A 1-34, nr. 34, fol. 105 (see also Scholten and Hoyle 2006, 115). These plaster portraits were valued at 4 guilders.

- 32.

Scholten and Hoyle 2006, 115.

- 33.

See e.g. Bredius 1912.

- 34.

The almanacs do not contain any information about the doors in the voorhuis, but they inform us that some other doors in the house were painted: in November 1666, De Graeff agreed with Willem Jacobsz van der Valck that he would paint two doors with a technique that was used to reproduce the effect of walnut tree wood (“noteboomen”) (SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 188 (1666), 18 November); at the end of 1685 he asked Paulus Fouchier to paint a Mercurius on the door of his house office (SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 205 (1985), 11 December), and six ‘room doors’ (“Camerdeuren”) and two small doors (one of which in the attic) with unspecified subjects in January 1686 (SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 206 (1986), 10 January).

- 35.

- 36.

Rijksmuseum, BK-NM-1010.

- 37.

Jacob Appel, Poppenhuis van Petronella Oortman, ca. 1710 (Rijksmuseum, SK-A-4245).

- 38.

4For a more detailed account on the development of the Dutch classicism, see Hopkins and Witte (1996, Ottenheym (2007, 2010). Scamozzi’s work was already available in the Netherlands shortly after 1620 (Ottenheym 2007, 188). A number of local editions, starting with the translation of Book VI on the Five Orders of architecture published by Cornelis Danckerts in 1640, made this work more accessible and contributed to its fortune in this country. In fact, it must be noted that this work became available in the Netherlands before Palladio’s treatise, whose publication took place in 1646 (Hopkins and Witte 1996, 277). For the catalogue of the various editions of Scamozzi’s work published in the Netherlands, see Hopkins and Witte (1996, 295–302).

- 39.

Catalogus Librorum Viri Amplissimi Petri De Graaff (dum viveret) Toparchae In Zuydt-Polsbroeck, Purmerland, Ilpendam, &c. &c. Urbis Amstelodamensis Scabini &c. Quorum auctio habebitur in Aedibus Viduae T. Boom, & haeredum H. Boom. Op de Cingel by de Jan-Roonpoorts Tooren. Die Martis 9. Julii MDCCIX. Amstelodami, In Officina Bomiana Ubi Catalogi distribuuntur. This catalogue is kept at the National Library of Russia in St. Petersburg (Shelf number NL: 16.133.9.36). Its analysis by the author is currently underway and will appear in C. Piccoli, Pieter de Graeff (1638-1707) and his treffelyke bibliotheek: Exploring and reconstructing an early modern private library, Leiden: Brill (accepted for publication).

- 40.

Eerste deel der Bouw-Kunst (…), Leiden, 1664 (Catalogus Librorum (…) Petri De Graaff (…): p. 35, nr. 294).

- 41.

Lyon, 1586 (Catalogus Librorum (…) Petri De Graaff (…): p. 35, nr. 285).

- 42.

From the almanacs we know the names of De Graeff’s master mason (Thomas Munster) and of his master carpenter (Cornelis Adriaensz Verduyn), see e.g. SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 187 (1665), 17 April; inv. nr. 188 (1666), 20 or 24 March; inv. nr. 191 (1671), 17 January.

- 43.

SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 188 (1666), August (a specific day is missing; the entry is written between the entries dated 25 and 30 August).

- 44.

The surveys of the building were carried out by the author together with Gabri van Tussenbroek and Bart Reuvekamp.

- 45.

A question remains open in relation to the exact position of this door, since a later larger portal has substituted the original doorway. The reconstructed location of the door is therefore inferred by taking into account the symmetry of the room and the volume of the service stairs which were originally behind the right part of the wall.

- 46.

The presence of a window over the main entrance corresponds to the common design of the time and is confirmed by an entry in the almanacs where De Graeff recorded that he received 90 screws for the windows of the attics, the voorhuis and the zydelkamer (SAA, Inventaris van het Archief van de Familie De Graeff (nr. 76), inv. nr. 188 (1666), 13 November).

- 47.

Two alternative reconstruction hypotheses of the floor tile pattern are discussed in more detail in Huurdeman and Piccoli (2021), and can be explored in the prototype Virtual Interiors webviewer at https://www.virtualinteriorsproject.nl/output/ (last accessed August 2021)

- 48.

See Gordin et al. (1996).

- 49.

Further on this, see Huurdeman and Piccoli (2021)

- 50.

See e.g. the physical reconstruction of Rembrandt’s house, completed in 1999, which has triggered a debate about the ethics of this type of interventions and the authenticity of the results (e.g. Laan and Vroom 1997; Koelemeijer 1998; van den Boogert 1999). For other case studies and a reflection on this subject, see Nakaris and Avgerinou-Kolonia (2016). In our case, the plan of making the results of this work available on location has been halted by the permanent closure of the museum in 2020.

- 51.

http://www.londoncharter.org/ (last accessed August 2021).

- 52.

http://sevilleprinciples.com/ (last accessed August 2021).

- 53.

For various project-based ways of visualizing uncertainty see, e.g. the Villa of Livia project for one of the earliest examples in the archaeological domain (Forte 2007), and Noordegraaf et al. (2016) in the history of cinema going. See also Huurdeman and Piccoli (2021) for a more detailed discussion of this topic.

- 54.

See https://virtualinteriorsproject.nl/ (last accessed August 2021) and Huurdeman (2020).

- 55.

These aspects related to the case study of the De Graeff’s voorhuis are further discussed in Huurdeman and Piccoli (2021) and Huurdeman 2021. The proposed 3D reconstruction of De Graeff’s entrance hall can be explored at https://www.virtualinteriorsproject.nl/output/ (last accessed August 2021). A screencast showcasing the functionalities that are currently implemented in the prototype web-viewer is available at https://doi.org/10.21942/uva.14424218 (last accessed August 2021). See also Huurdeman et al. 2021 for the Linked Data integration.

References

Aalst, Loek van and Annigje Hofstede. 2011. Noord-Nederlandse meubelen van renaissance tot vroege barok 1550–1670. Utrecht: Hes & de Graaf.

Baarsen, Reinier. 2007. Wonen in de Gouden Eeuw 17de-eeuwse Nederlandse meubelen. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam: Nieuw Amsterdam Uitgevers.

Beaudry, Mary C. 2015. Households beyond the house. On the Archaeology of Materiality of historical households. In Beyond the Walls: New Perspectives on the Archaeology of Historical Households, ed. K. R. Fogle, J. A. Nyman, and M. C. Beaudry, 1–22. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Boogert, Bob van den. 1999. Bouwkundige reconstructie van het Rembrandthuis voltooid. Binnenstad 179. https://www.amsterdamsebinnenstad.nl/binnenstad/179/rembrandt.html. Accessed August 2021.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1979. La distinction: Critique sociale du jugement. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit.

Bredius, Abraham. 1912. Iets over de copie van Gerrit Lundens naar Rembrandt’s “Nachtwacht”. Oud Holland 30 (4), 197–200.

Denard, Hugh. 2012. A New Introduction to the London Charter. In Paradata and Transparency in Virtual Heritage, ed. A. Bentkowska-Kafel, H. Denard and D. Baker, 57–71. Farnham: Ashgate.

Eikema Hommes, Margriet van and Piet Bakker. 2008. Hoogachtbaarheid en ontzaglijke grootheid: De burgermeesterskamer van het stadthuis van Enkhuizen. In Romeyn de Hooghe: de verbeelding van de late Gouden Eeuw, ed. H. van Nierop, 222–43. Zwolle: Waanders.

Faber, Johannes. 1980. Inhabitants of Amsterdam and their possessions, 1701–1710. In Probate Inventories. A New Source for the Historical Study of Wealth, Material Culture and Agricultural Development. Papers Presented at the Leeuwenborch Conference (Wageningen, 5–7 May 1980), ed. A. van der Woude and A. Schuurman, 149–76. Utrecht: Brill | Hes & DeGraaf.

Fock, C. Willemijn. 1982. Review of Thornton 1978. Oud Holland 96: 198–200.

Fock, C. Willemijn. 1998. Werkelijkheid of schijn. Het beeld van het Hollandse intérieur in de zeventiende-eeuwse genreschilderkunst. Oud Holland 112: 187–246.

Fock, C. Willemijn. 1999. Het decor van huiselijk vermaak ten tijde van de republiek. In Vermaak van de elite in de vroegmoderne tijd, ed. J. de Jongste, J. Roding and B. Thijs, 40–72. Hilversum: Verloren.

Fock, C. Willemijn. 2001. Het Nederlandse interieur in beeld, 1600–1900. Zwolle: Waanders.

Fock, C. Willemijn. 2007a. Het interieur in de Republiek 1670–1750: (g)een plaats voor schilderkunst? In De kroon op het werk. Hollandse schilderkunst 1670–1750, ed. E. Mai, S. Paarlberg, G. J. M. Weber, 65–84. Dordrecht: Dordrechts Museum.

Fock, C. Willemijn. 2007b. Het stempel van de bewoner. Leiden: Leiden University.

Forte, Maurizio. 2007. La villa di Livia: un percorso di ricerca di archeologia virtuale. Roma: L'Erma di Bretschneider.

Frischer, Bernard, Franco Niccolucci, Nick Ryan and Juan Antonio Barceló. 2002. From CVR to CVRO: The Past, Present and Future of Cultural Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of VAST 2000, ed. F. Niccolucci, 7–18. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Goffman, Erving. 1956. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Social Sciences Research Centre.

Gordin, Douglas N., Daniel C. Edison and Louis M. Gomez. 1996. ‘Scientific Visualization as an Interpretive and Expressive Medium’. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Learning Sciences, July 1996, Evanston, IL, Charlottesville, ed. C. Edelson and E. A. Domeshek, 409–14. VA: AACE.

Groeneveld, Inger. 2010–2011. In goede orde veranderlijk geordineerd. Schriftelijke bronnen over (marmer)stenen vloeren in het Nederlandse interieur van de 17de en 18de eeuw. Tijdschrift voor Interieurgeschiedenis en Design 37: 21–51. https://doi.org/10.2143/GBI.37.0.3017262.

Hales, Shelley. 2003. The Roman House and Social Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hanson, Julienne. 2003. Decoding homes and houses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hanson, Julienne and Bill Hillier. 1982. Domestic space organization. Two contemporary space-codes compared. Architecture and Behaviour 2: 5–25.

Havard, Henry. 1887. Dictionnaire de l'ameublement et de la décoration depuis le XIIIe siècle jusqu'à nos jours, vol. 1, Paris: Ancienne maison Quantin, Librairies-imprimeries réunies.

Hendon, Julia A. 2004. Living and Working at Home: The Social Archaeology of Household Production and Social Relations. In A Companion to Social Archaeology, ed. R. W. Preucel and L. Meskell, 272–86. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hillier, Bill and Julienne Hanson 1984. The Social Logic of Space. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hopkins, Andrew and Arnold Witte. 1996. From deluxe architectural book to builder's manual: the Dutch editions of Scamozzi’s L'Idea della Architettura Universale. Quaerendo 26 (4): 274–302.

Huurdeman, Hugo. 2020. Visualizing a radio of the past using technology of the future. https://www.beeldengeluid.nl/en/knowledge/blog/visualizing-radio-past-using-technology-future. Accessed August 2021.

Huurdeman, Hugo, and Chiara Piccoli. 2021. 3D reconstructions as research hubs: Geospatial interfaces for real-time data exploration of 17th cent Amsterdam domestic interiors. Open Archaeology 7: 314–336.

Huurdeman, Hugo. 2021. ‘Analyze & Experience: Towards a Research Environment for 3D Reconstructions’ https://www.virtualinteriorsproject.nl/2021/08/04/towards-a-3d-research-environment. Accessed August 2021.

Huurdeman, Hugo, Chiara Piccoli and Leon van Wissen. 2021. Linked Data in a 3D Context: Experiential Interfaces for Exploring the Interconnections of 17th-Century Historical Data. Paper presented at the DH Benelux conference (Leiden, 2–4 June 2021) available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4889856. Accessed August 2021.

Jameson, Michael. 1990a. Private Space in the Greek City. In The Greek City from Homer to Alexander, ed. O. Murray and S. Price. 171–98. Oxford: Clarendon Press / New York: Oxford University Press.

Jameson, Michael. 1990b. Domestic space in the Greek city-state. In Domestic Architecture and the Use of Space, ed. S. Kent, 92–113. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kent, Susan. 1990. New Directions in Archaeology: Domestic Architecture and the Use of Space: An Interdisciplinary Cross-Cultural Study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Koelemeijer, Judith. 1998. Een kijkhuis vol valse meubels Het Rembrandthuis wordt net echt zeventiende-eeuws. De Volkskrant 20 februari 1998. https://www.volkskrant.nl/cultuur-media/een-kijkhuis-vol-valse-meubels-het-rembrandthuis-wordt-net-echt-zeventiende-eeuws~be74a666/. Accessed August 2021.

Koldeweij, Eloy. 2008. ‘Wat er op de vloer omme-gaet’: poppenhuisvloeren en de realiteit. In Over de vloer. Met voeten getreden erfgoed, ed. E. Koldeweij, 132–53. Zwolle: Waanders.

Korevaar, Gerbrand and Gwen Tauber. 2014. Gerard ter Borch repeats: on autograph portrait copies in the work of ter Borch (1617–1681). Bulletin of the Rijksmuseum 4: 348–81.

Laan, Barbara and Wim Vroom. 1997. Sloop interieur De Bazel van Rembrandthuis te Amsterdam? Cuypersbulletin 3: 14–6.

Lessi, Federica. 2000. Velluti Ottomani dei secoli XVI e XVII del Museo Nazionale del Bargello di Firenze, Emblemata 6: 113–37.

Loughman, John and John Michael Montias. 2000. Public and Private Spaces: Works of Art in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Houses (Studies in Netherlandish Art and Cultural History). Zwolle: Waanders.

Mare, Heidi de. 1993. The Domestic Boundary as Ritual Area in Seventeenth-Century. In Urban Rituals in Italy and the Netherlands: Historical Contrasts in the Use of Public Space and the Urban Environment, ed. H. de Mare and A. Vos, 108–31. Assen: Van Gorcum.

Mare, Heidi de. 2003. Het huis en de regels van het denken. Een cultuurhistorisch onderzoek naar het werk van Simon Stevin, Jacob Cats en Pieter de Hooch, (4 vols), Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, PhD thesis (28 January 2003).

Meischke, Rudolph and Henk J. Zantkuijl. 1969. Het Nederlandse Woonhuis van 1300–1800 (Vijftig jaar Vereniging ‘Hendrick de Keyser’). Haarlem: Tjeenk Willink.

Moseley-Christian, Michelle. 2010. Seventeenth century ‘pronk poppenhuisen’: Domestic space and the ritual function of Dutch dollhouses for women. Home cultures 7 (3): 341–64.

Muurling, Sanne. 2002. Huiselijkheid tussen ideaal en materiële werkelijkheid. Een materiële microgeschiedenis van veertien Amsterdamse huishoudens. Holland 44 (3): 119–30.

Nakasis, Athanasios and Sofia Avgerinou-Kolonia (ed.). 2016. Reconstructions: European perspective, Booklet of the ICOMOS Europe Group Meeting, 6–7 June 2016, Athens, Greece. Athens: Propobos Publications.

Nierop, Henk van (ed.) 2008. Romeyn de Hooghe: de verbeelding van de late Gouden Eeuw. Zwolle: Waanders.

Noordegraaf, Julia, Opgenhaffen, Loes and Norbert Bakker. 2016. Cinema Parisien 3D: 3D visualisation as a tool for the History of Cinemagoing. Alphaville 11 (3): 45–61.

Otten, Jeanine. 1995. Kaarttekenaars en kaartafzetters in de dagboeken van Pieter de Graeff (1638–1707). Caert Thresoor 14 (3): 53–8.

Ottenheym, Konrad. 2007. A Bird’s-Eye View of the Dissemination of Scamozzi’s Treatise in Northern Europe. Annali di architettura 18–19: 187–98.

Ottenheym, Konrad. 2010. Schoonheid op maat. Vincenzo Scamozzi en de architectuur van de Gouden Eeuw. Amsterdam: Architectura & Natura Pers.

Piccoli, Chiara. 2018. Visualizing cityscapes of Classical antiquity: From early modern reconstruction drawings to digital 3D models. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Pijzel-Dommisse, Jet. 2000. Hollandse Pronkpoppenhuis interieur en huishouden in de 17de en 18de eeuw. Zwolle: Waanders.

Purves, Alex C. 2010. Space and Time in Ancient Greek Narrative. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rapoport, Amos. 1969. House Form and Culture. Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

Scholten, Frits. 2010. Artus Quellinus. Beeldhouwer van Amsterdam. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum.

Scholten Frits and Michael Hoyle. 2006. Quellinus's Burgomasters: A Portrait Gallery of Amsterdam Republicanism. Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 32 (2/3): 87–125.

Schuurman, Anton. 1980. Probate inventories: research issues, problems and results. In Probate Inventories. A New Source for the Historical Study of Wealth, Material Culture and Agricultural Development. Papers Presented at the Leeuwenborch Conference (Wageningen, 5–7 May 1980), ed. A. van der Woude and A. Schuurman, 19–31. Utrecht: Brill / Hes & DeGraaf.

Schama, Simon. 1997 [1987]. The Embarrassment of Riches: an interpretation of Dutch culture in the Golden Age. New York: Vintage Books.

Sluijter, Eric Jan. 2001. “All striving to adorne their houses with costly peeces” Two Case Studies of Paintings in Wealthy Interiors. In Art and Home: Dutch Interiors in the Age of Rembrandt, ed. M. Westermann, 103–27. Zwolle: Waanders.

Tussenbroek, Gabri van. 2016a. Functie en indeling van het Amsterdamse woonhuis aan de hand van een aantal zestiende-eeuwse boedelinventarissen. KNOB 3: 113–31.

Tussenbroek, Gabri van. 2016b. Assembling the World. The International Building Materials Trade in Amsterdam (1613–1795). In The Amsterdam Canals: World Heritage, ed. P. Vlaardingerbroek, 108–47. Amsterdam: Bas Lubberhuizen.

Vlaardingerbroek, Pieter. 2011. Het paleis van de Republiek. Geschiedenis van het stadhuis van Amsterdam. Zwolle: Wbooks.

Vlaardingerbroek, Pieter. 2019. An appropriated history: The case of the Amsterdam Town Hall (1648–1667). In The Quest for an Appropriate Past in Literature, Art and Architecture, ed. K. A. E. Enenkel and K. A. Ottenheym, 455–81. Leiden: Brill.

Westermann, Mariët. 2001. “Costly and Curious, full off pleasure and home contentment” Making Home in the Dutch Republic. In Art and Home: Dutch Interiors in the Age of Rembrandt, ed. M. Westermann, 15–81. Zwolle: Waanders.

Wijsenbeek-Olthuis, Thera Francine. 1996. Het Hollandse interieur in beeld en geschrift. Theoretische Geschiedenis 23 (2): 145–163.

Zaandvliet, Kees. 2006, De 250 rijksten van de Gouden Eeuw, Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum / Nieuw Amsterdam.

Acknowledgements

This work was part of “Virtual Interiors as Interfaces for Big Historical Data Research: Spatially Enhanced Publications of the Creative industries of the Dutch Golden Age” project financed by the NWO Smart Culture—Big Data/Digital Humanities program (2018–2022). The author would like to thank Gabri van Tussenbroek for his advice during this research, Bart Reuvekamp for his help in exploring the De Graeff family archive and for his transcriptions, Judith Brouwer for checking the transcriptions, and Hugo Huurdeman for his feedback on the data spreadsheets’ structure. Also, thanks to Gabri van Tussenbroek, Charles van den Heuvel and Julia Noordegraaf for their comments on an earlier version of this text.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Piccoli, C. (2023). Home-Making in 17th Century Amsterdam: A 3D Reconstruction to Investigate Visual Cues in the Entrance Hall of Pieter de Graeff (1638–1707). In: Landeschi, G., Betts, E. (eds) Capturing the Senses. Quantitative Methods in the Humanities and Social Sciences. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23133-9_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23133-9_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-23132-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-23133-9

eBook Packages: Mathematics and StatisticsMathematics and Statistics (R0)