Abstract

In their important work, Facing the Future (Oxford 2001), Nuel Belnap and his collaborators, Michael Perloff and Ming Xu, say the following (p. 204): “We agree with Kane (1996) that ... the question whether a kind of freedom that requires indeterminism can be made intelligible deserves ... our most serious attention, and indeed we intend that this book contribute to what Kane calls ‘the intelligibility question.”’ I believe their book does contribute significantly to what I have called “the Intelligibility Question” for free will (which as I understand it is the question of how one might make intelligible a free will requiring indeterminism without reducing such a free will to either mere chance or to mystery and how one might reconcile such a free will with a modern scientific understanding of the cosmos and human beings). The theory of agency and choice in branching time that Belnap has pioneered and which is developed in detail in Facing the Future is just what is needed in my view as a logical foundation for an intelligible account of a free will requiring indeterminism, which is usually called libertarian free will. In the first two sections of this article, I explain why I think this to be the case. But the logical framework which Belnap et al. provide, though it is necessary for an intelligible account of an indeterminist or libertarian free will, is nonetheless not sufficient for such an account. In the remaining sections of the article (3–5), I then discuss what further conditions may be needed to fully address “the Intelligibility Question” for free will and I show how I have attempted to meet these further conditions in my own theory of free will, developed over the past four decades.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 The Intelligibility Question: An Introductory Narrative

In their important work, Facing the Future (hereafter FF), Nuel Belnap and his collaborators, Michael Perloff and Ming Xu, say the following (p. 204): “We agree with Kane (1996) that ... the question whether a kind of freedom that requires indeterminism can be made intelligible deserves, instead of a superficial negative, our most serious attention, and indeed we intend that this book contribute to what Kane calls ‘the intelligibility question.”’ I believe their book does contribute significantly to what I have called “the Intelligibility Question” for free will. The theory of agency and choice in branching time that Belnap has pioneered and which is developed in the book in detail is just what is needed in my view as a logical foundation for an intelligible account of a kind of free will that requires indeterminism, which is usually called libertarian free will. The logical framework they provide, though necessary for an intelligible account of such an indeterminist or libertarian free will, is however not sufficient for such an account. And I want to discuss in this article what further conditions may be needed to adequately address “the Intelligibility Question.”

First, I need to say more about what the Intelligibility Question is. Since ancient times philosophers have doubted that one could make sense of a kind of free will that would require indeterminism. Such a free will, it was commonly argued, must reduce freedom of choice either to mere chance or to mystery. When agents face a free choice we assume that different possible pathways (or histories in the language of FF) are open to them; and which possible pathway or history becomes the actual one will depend in part at least on the agents themselves and how they choose. But if a free choice is undetermined then it would appear that which historical future becomes the actual one would be a matter of chance and so not within the control of the agent. An undetermined event, it is often argued, occurs spontaneously and is not controlled by anything, hence not controlled by the agent. If, for example, a choice occurred by virtue of a quantum jump or other undetermined events in an agent’s brain it would seem a fluke or accident rather than a responsible choice. Thus it is often argued that indeterminism would not enhance our freedom, but would rather undermine it. For reasons such as these and many others, thinkers have argued for centuries that undetermined free choices would be “arbitrary,” “capricious,” “random,” “irrational,” “uncontrolled,” “mere matters of luck or chance,” and not really free and responsible choices at all. The Epicurean philosophers of old argued that there would be no room in nature for free will if the atoms did not sometimes “swerve” in undetermined ways. But the many ancient critics of their view, including Stoics and skeptics, scoffed at such an idea, arguing that the mere chance swerve of atoms could not amount to freedom of choice.

Defenders of an indeterminist or libertarian free will have had a poor record through the centuries of answering these familiar charges. Realizing that free will could not merely be indeterminism or chance, they have appealed to various obscure or mysterious forms of agency or causation to make up the difference. Immanuel Kant argued that we cannot explain free will in scientific terms, even though we require it for belief in morality. To make sense of it we have to appeal to the agency of what he called a “noumenal self” outside space and time that could not be studied in scientific terms. Many other philosophers from Descartes onward have believed that only an appeal to a substance dualism of mind and body could make sense of free will. Science might tell us there was some indeterminacy in nature or a place for causal gaps in the brain, but a nonmaterial self would have to fill those causal gaps in the physical world by intervening in the natural order. Nobel physiologist, John Eccles, in the twentieth century, for example, argued that there might be some place for indeterminism in synaptic transmission of neural impulses in the brain (Eccles 1994). But he went on to argue that if we were to make sense of free choice we would have to appeal in dualist fashion to a “transempirical power center” that would intervene in the brain to fill the causal gaps thus left by the indeterminism. And many other philosophers have referred to yet other libertarian strategems to account for free will, such as uncaused causes, prime movers unmoved and special kinds of agent or immanent causation that cannot be explained in terms of ordinary modes of causation in terms of events familiar to the sciences.

In summary, the charge down through the centuries has been that a free will requiring indeterminism was unintelligible or incoherent or impossible. Libertarian views of free will must either reduce free will to mere chance or require some appeal to mysterious forms of agency or causation that had no place in the modern scientific picture of the world. As Nietzsche (2002, Sect. 8) summed up the matter in his inimitable prose, freedom of the will in the “superlative metaphysical sense” (as he put it), which requires that free agent somehow be a causa sui, is “the best self-contradiction that has been conceived so far” by the mind of man.

The “Intelligibility Question” as I formulated it was a response to this long history of debate and may be stated in this way: Can one make sense of, or give an intelligible account of, a free will requiring indeterminism without reducing it to either mere chance, on the one hand, or mystery, on the other?

To explain how I have attempted to answer this question in my own work, a bit of history will be helpful. When I first began thinking about the free will problem in the 1960s, the landscape of the free will debate was much simpler than today. The unstated assumption was that if you had scientific leanings, you would naturally be a compatibilist about free will, believing it to be compatible with determinism, unless you denied it all together as did skeptics and hard determinists. And if on the other hand you were a libertarian about free will, believing in a free will that was incompatible with determinism, it was assumed that you must invariably appeal to some kind of obscure forms of agency to make sense of it—to uncaused causes, immaterial minds, noumenal selves, prime movers unmoved, or other examples of what P. F. Strawson called the “panicky metaphysics” of libertarianism in his important 1962 essay, “Freedom and Resentment.”

If I may add a personal note here, I was a graduate student at Yale University when Strawson’s essay first appeared in 1962 and it was there that I first knew Nuel Belnap. He was one of my logic teachers at the time, along with Alan Anderson and Fred Fitch. (Rich Thomason, an important contributor to the branching time logic presupposed in FF, was a fellow graduate student at Yale at the time.) Belnap was not working on the logic of agency and choice in branching time at that point to my knowledge. That was to come later. As I recall, Belnap was working with Anderson at the time developing a new theory of “relevance logic,” another area in which he has made significant contributions.

My own dissertation director and philosophical mentor at this time at Yale was Wilfred Sellars, who soon after was to move to the University of Pittsburgh, along with Belnap and Anderson. Sellars was a compatibilist about free will, like the vast majority of scientists and philosophers of that era, and he did not believe that a libertarian free will requiring indeterminism could be accounted for without appealing to obscure forms of agency of the kinds Strawson had called “panicky metaphysics.” Appealing to an influential distinction that Sellars had himself introduced into contemporary philosophical discourse, he granted that free will in some sense was an integral part of what he called the manifest image of humans and their world. But he did not believe that a traditional indeterminist or libertarian free will could be reconciled with what he called the scientific image of the world; and he challenged me to show otherwise. With the naïveté characteristic of a young graduate student, I suggested that I would return in a few weeks with an answer to this challenge. It has turned out to be a project of somewhat longer duration, still ongoing.

It was a surprise therefore some 40 years later when I received in the mail a complementary copy of Facing the Future, sent to me by Nuel Belnap. It was not sent to me as a former student, but rather as someone who had in the intervening years written extensively on the free will problem, attempting to make sense of the libertarian free will, who might find the book congenial and a significant contribution to that project. (He had in fact forgotten I had ever been a student of his so many years ago and I had to remind him of the fact.) That our intellectual paths should cross this way after so many years was indeed fortuitous. For, as noted above, I do believe that FF provides a logical framework that is congenial to the project of making sense of a free will requiring indeterminism and hence to addressing the Intelligibility Question.

2 Action, Indeterminism, and Facing the Future

I will first give some reasons for thinking this is the case regarding the logical framework of FF before turning to further issues that have to be addressed in order to fully answer the Intelligibility Question. First, there are a number of issues and topics in the philosophy of action related to free will that are made more precise by the stit logic developed in FF, which philosophers who deal with action theory (usually only in informal ways) would do well to take note of. The distinction between the achievement stit and the deliberative stit (pp. 32–40) is particularly important in my view for discussing issues about free will. The achievement stit involves an earlier moment of choice or action that guarantees the later outcome A of an action. The deliberative stit, by contrast, is evaluated at the moment of choice itself, the very moment at which the agent sees to it that the outcome A will occur. The outcome A is guaranteed by the present choice at the moment of choice itself. Both achievement stits and deliberative stits would play a role I believe in an adequate account of free will. But the idea behind the achievement stit must also be expanded in a certain way to account for free will as I understand it. As I will argue, acts done “of one’s own free will,” it must be allowed, can also be achievements of multiple choices and actions performed at earlier times which causally influence, even if they do not always guarantee, later choices or actions.

Second, the notion of “settled” truth (pp. 29–32) which is basic to the framework of FF is fundamental to making sense of libertarian free will and indeed to understanding the traditional problem of free will itself. The operative intuition is that when an agent faces a free choice (in particular, a deliberative stit), which choice will be made is not settled true at any time before the choice itself is made. Doctrines of determinism have been thought to be a threat to free will to the extent that they imply that for every choice or action, whether or not it will occur is settled true at some time before it does occur or not. Determinism can be and has been defined in many different ways. But it is this implication of doctrines of determinism in terms of settled truth that has historically been thought to be a threat to free will. The logical framework of FF allows one to express this threat in a clear way.

Third, the framework of FF also helps to resolve a host of controversial issues that have long been discussed in the literature of free will regarding the truth value of future tensed sentences concerning human choices and actions. Since Aristotle, a common assumption has been that if free choices and actions are neither fated nor determined, then future tensed sentences concerning them must be neither true nor false. But this assumption has led to numerous puzzles that are perceptively described and many of which in my view are helpfully resolved in FF (pp. 144–176). To treat future tensed sentences of these kinds as open sentences lacking the assignment of a history parameter seems to me the right way to go to resolve these puzzles. To say that a future tensed sentence concerning a free choice is neither true nor false is not to say that it has some third truth value or a third special status. Given a model and a context, an open sentence about an indeterminate future of this kind will have a truth value, once a suitable value is applied for each of the parameters, including the history parameter. This solution to the assertion problem for such future tensed propositions seems to me quite congenial to libertarian accounts for free will, as is the related solution in FF to the problem of “the thin red line” (pp. 160–174). The solutions of the book to these problems can of course be questioned and its solution to the problem of the thin red line is questioned by other contributors to this volume. I am inclined to agree with its solution to the problem of the thin red line, but will not argue the matter here. I will merely register the general conviction that something like the solutions to these problems about future tensed propositions proposed in FF is what is needed for a coherent conception of free will that requires indeterminism.

Fourth, the logical framework of FF helps to clarify a number of other issues in the philosophy of action and in debates about free will and responsibility. These include its perceptive account of the distinction between “refraining” from an action and simply not performing the action, a distinction which philosophers of mind and action have often puzzled over (pp. 40–45). The interpretation of the distinction in terms of the logic of stit helps one to clearly see how refraining from an action can be a kind of action even though it also involves not performing an action. Another area where the framework of FF is helpful is in spelling out the different possible meanings of the much discussed expression “could have done otherwise” in the free will literature (pp. 255–270). Belnap at al. show how certain puzzles in the literature concerning the relation of moral responsibility to the ability to do otherwise can be illuminated by distinguishing these different meanings of the ability to do otherwise. Their framework also helps to clarify and formalize the important distinction between so-called “soft facts” and “hard facts” about the past, a distinction that plays a role in many debates about free will and determinism, but is not always carefully defined (pp. 145–174). In these ways and in others, philosophers who deal with the theory of action and free will in more informal ways have much to learn from the formal framework developed by Belnap at al. in this book.

3 From Action to Free Will

While the framework of FF makes a significant contribution to debates about free will in these and other ways, there is at least one point on which I would depart from it—or perhaps better, qualify it to some degree—in giving an account of free will. FF assumes that indeterminism and the logic of branching time presupposed by it are required to account for action in general of any kinds, whereas on my view, while indeterminism and branching time are required to explain free will (or more precisely, actions done “of one’s own free will”), they are not required to account for action in general. I would find it congenial, to be sure, if it could be shown that all action and agency did require indeterminism, for then, a fortiori, acts of free will would as well. But I am not convinced of this stronger claim and would need to be shown otherwise, for the following reasons.

There seems to be a primordial sense of action and agency that is admittedly presupposed by free will, but leaves open the question of whether determinism or indeterminism is true. According to this primordial sense, to act is to guide behavior toward a goal or purpose in accordance with a plan and it involves the capacity to readjust both goal and plan (ends and means, one might also say) in the light of feedback from the environment. Action in this primordial sense involves a certain kind of control of an agent over behavior that we might refer to as teleological guidance control, given that the behavior in question is goal-directed and involves guidance. Action in this sense of goal-directed, guided behavior is something other living things are capable of, not merely human beings, though humans have further and more sophisticated higher-order capacities to evaluate and re-evaluate both ends and means. I believe action in this primordial sense can exist in principle in determined worlds. One reason for believing so is that the ability to guide behavior toward a goal does not of itself imply that the agent also has the ability to do otherwise, i. e., to guide behavior to a different goal. Though, importantly, action in this primordial sense is also compatible with some measure of indeterminism. So acknowledging it as a significant form of action does not settle issues about determinism and indeterminism.

It is when we ask further questions about this primordial conception of action, in my view, that we raise distinctive issues about the freedom of the will. A central question for example is this: Whence comes the purposes and plans themselves that guide behavior, rendering it action in this primordial sense? Do the purposes and plans (ends and means) that guide behavior have their sources or originate in the agents themselves who act, or do these purposes and plans ultimately come entirely from sufficient causes outside the agent and over which the agent does not have control? This is a variant of the free will question; and one can see from it why determinism has been thought by many historically to be a threat to free will. If determinism were true there would be sufficient causes outside the agents and over which the agents did not have control for whatever purposes and plans, ends and means, agents might pursue—sufficient causes going back into the remote past for why they had the purposes and plans they did have rather than some others. Agents might still have the power to control behavior in accordance with their purposes and plans (i.e. to act in the primordial sense), but they would not be the ultimate sources of the purposes and plans that guide their behavior. That is, they might be able to do what they willed, but they would not be the ultimate creators of what it is that they willed, and in that sense would not be acting “of their own free will” in the sense of “a will of their own free-making.”

Yet this notion of freedom of the will as ultimate creation of purposes (“a will of one’s own free-making”) is itself highly problematic. It immediately conjures up Nietzsche’s image, mentioned earlier, of an agent who exercises free will as some kind of ultimate cause of itself, a causa sui, the “best self-contradiction conceived so far by the mind of man.” The idea of a will of one’s own free-making suggests a troubling backtracking regress, since to be the ultimate creator of one’s own present will and purposes, one would have to be so by virtue of prior choices and actions which would be motivated by still earlier purposes and plans, which earlier purposes and plans in turn could not have sufficient causes outside the agent and over which the agent did not have control, and so must be created by still earlier choices or actions of the agent, and so on indefinitely.

This regress could be stopped, to be sure, if some choices or actions in the agent’s life history did not have sufficient causes at all and so were undetermined. But, while this solution points in the right direction (showing why indeterminism is thought to be important for freedom of will), it brings us back to the dilemma that has historically given rise to the Intelligibility Question: If choices by which we (ultimately) create our purposes and plans were undetermined, it seems that they would not be in our control, since undetermined events occur by chance and are not controlled by anything, hence not by agents. The alternative, as noted, would be to appeal to mysterious forms of agency, to uncaused causes, prime movers, and the like; and in such manner the appeal to ultimate creation of purposes leads us back to the dilemma of chance or mystery once again.

To complicate matters, there is a further problem about indeterminism with regard to free will that is also important for dealing with the Intelligibility Question. Unlike the previous dilemma, it is a problem that often gets overlooked in historical and contemporary discussions about free will, though as I have argued for several decades, it is crucial for understanding the very notion of the freedom of the will (see, e.g., Kane 1985, 1996, 2002b, 2007).

This problem is that even if one grants that indeterminism is a necessary condition for genuinely free choices and actions, it turns out that it is not a sufficient condition for freedom of will. The reason is that when we wonder about whether the wills of agents are free, it is not merely whether they could have done otherwise that concerns us, even if the doing otherwise is undetermined. What interests us is whether they could have done otherwise voluntarily, intentionally, and rationally, rather than merely by accident or mistake, unintentionally, inadvertently, or irrationally. Or, putting it more generally, we are interested in whether agents could have acted voluntarily (in accordance with their wills), intentionally (on purpose rather than accidentally or inadvertently), and rationally (with good reasons) in more than one way rather than in only one way, and in other ways merely by accident or mistake, unintentionally, inadvertently, or irrationally.

I call such conditions–of more-than-one-way voluntariness, intentionality and rationality–“plurality conditions” for free will ((Kane 1996, 107–111)). And I call the ability to choose or act in more than one way voluntarily, intentionally and rationally, i.e. in accordance with these conditions, plural voluntary control (PVC). These plurality conditions seem to be deeply embedded in our intuitions about free choice and action. We naturally assume, for example, that freedom and responsibility would be deficient if it were always the case that we could only do otherwise by accident or mistake, unintentionally, involuntarily, or irrationally. It is true that libertarian free will requires that more than one branching pathway (history) into the future be “open” to agents in the manner described in FF (p. 136). But it also requires something about the way that agents select from among these open pathways: Whichever ones they select, if they are to do so “of their own free will,” they must do so voluntarily, intentionally and rationally (at will, as we say), rather than merely accidentally, unintentionally or irrationally.

4 Self-forming Actions (SFA’s)

We are now in a position to consider what further steps may be necessary to fully address the Intelligibility Question.

The first important step is to note that, as the preceding discussion suggests, indeterminism need not be involved in all acts done “of our own free wills.” Often we act from a will (character, motives and purposes) already formed. But it is “our own free will” by virtue of the fact that we formed it to some degree by other choices or actions in the past for which we could have done otherwise and which were undetermined. If this were not so there is nothing we could have ever done differently in our entire lifetimes to make ourselves and our wills different than they are—a consequence that I believe is incompatible with our being at least to some degree ultimately responsible for being the way we are, and for the wills we do have, and hence ultimately responsible for the actions that flow from our wills. Compare Aristotle’s claim that if a man is responsible for wicked acts that flow from his character and purposes (his will) he must at some time in the past have been responsible for forming the wicked character and purposes from which these acts flow.

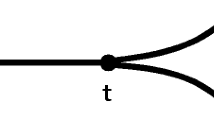

I call those choices or actions in agents’ life histories by which they formed their present wills and for which they could have done otherwise in a manner that was undetermined, “self-forming actions” or SFAs. (They would be “deliberative stits” in the language of FF.) I believe such self-forming actions occur at those difficult times in life when we are torn between competing visions of what we should do or become; and they are more frequent in everyday life than we may think. We might be torn between doing the moral thing or acting from ambition, or between powerful present desires and long term goals, or faced with difficult tasks for which we have aversions, etc. The uncertainty and inner tension we feel at such soul-searching moments of self-formation, I suggest, would be reflected in some indeterminacy in our neural processes themselves (perhaps chaotically amplified background neural noise) “stirred up,” one might say, by the conflicts in our wills. What is experienced personally as uncertainty at such moments would thus correspond physically to the opening of a window of opportunity that temporarily screens off complete determination by influences of the past. (By contrast, when we act from predominant motives and a “settled” will without such inner conflict, the indeterminacy is muted or damped and plays a less significant role.)

In such cases of self-formation, we are faced with competing motivations and whichever choice is made will require an effort of will to overcome the temptation to make the other choice. I thus postulate that, in such cases, multiple goal-directed cognitive processes would be involved in the brain, corresponding to competing efforts, each with a different goal, corresponding to the competing choices that might be made. In short, one might appeal to a form of parallel processing in the free decision-making brain. One of these neural processes has as its goal, the making of one of the competing choices (say, a moral choice), realized by reaching a certain activation threshold, while the other has as its goal the making of the other choice (e.g., a self-interested choice). Likewise, the competing processes have different inputs, moral motives (beliefs, desires, etc.), on the one hand, self-interested motives, on the other. And each of the processes is the realizer of the agent’s effort or endeavoring to bring about that particular choice (e.g. the moral choice) for those motives (e.g. moral motives), thus taking the input into the corresponding output; and the processes are so connected that if one should succeed, the other will shut down.

Because of the indeterminacy in each of these neural processes stirred up by the conflict in the will, however, for each, it is not certain that it will succeed in reaching its goal, i.e., an activation threshold that amounts to choice. Yet (and here is a further crucial step) if either process does succeed in reaching its goal (the choice aimed at), despite the indeterminacy involved, one can say that that choice was brought about by the agent’s effort or endeavoring to bring about that choice for those motives, because the process itself was the neural realizer of this effort and it succeeded in reaching its goal, despite the indeterminism involved.

Note that, in these circumstances, the choices either way would not be “inadvertent,” “accidental,” “capricious,” or “merely random,” because whichever choice is made will be brought about by the agent’s effort to make that particular choice for the reasons motivating that choice, reasons the agent will then and there endorse by making the choice itself. Indeed, the agents will have plural voluntary control (PVC) over the choices made, as defined earlier, since whichever choice is made will be made voluntarily (i.e. in accordance with the agent’s will, because the prior will is divided and the agent may consequently choose either way at will), intentionally (i.e. on purpose rather than accidentally or inadvertently, since the choice will result from the goal-directed effort to make that choice) and rationally (i.e. because the choice will be made for reasons motivating that choice which are reasons the agent has, and decides to act on then and there).

The idea in sum is to think of the indeterminism involved in free choice, not as a cause acting on its own, but as an ingredient in larger goal-directed or teleological activities of the agent, in which the indeterminism functions as a hindrance or interfering element in the attainment of the goal. The choices that result are then achievements brought about by the goal-directed activity (the effort) of the agent, which might have failed since they were undetermined, but one of which succeeds. Moreover, if there are multiple such processes aiming at different goals (as in the conflicted circumstances of an SFA), whichever choice may be made, will have been brought about by the agent’s effort to bring about that particular choice rather than some other, despite the possibility of failure due to the indeterminism.

In such circumstances, as a consequence, the indeterminism, though causally relevant to the choice, would not be the cause of the choice because it would have been an interfering element lowering the probability that that choice would be made from what it would have been if there was no interference. The causes of the choice, by contrast, would be those relevant factors that significantly raised the probability that this choice would be made rather than some other, such as the agent’s motives for making this choice rather than the other and the agent’s deliberative efforts to overcome the temptations to make the contrary choice. Were these factors not present there would be no chance this choice would be made because there would be no cognitive process of the agent aiming at it. Moreover, if the choice was caused by a deliberative cognitive process of the agent aiming at it, it would also be true to say that the agent caused the choice.

A further point is that when indeterminism thus functions as an obstacle to the success of a goal-directed activity of an agent, which succeeds in attaining its goal nonetheless, the indeterminism does not preclude responsibility. There are many examples demonstrating this fact (some first suggested by J. L. Austin and Elizabeth Anscombe). Here is one I have previously used. A husband, while arguing with his wife, in anger swings his arm down on her favorite glass-table top in an effort to break it. Imagine that there is some indeterminism in the nerves of his arm making the momentum of his swing indeterminate so that it is literally undetermined whether the table will break right up to the moment when it is struck. Whether the husband breaks the table or not is undetermined; and yet he is clearly responsible if he does break it, because the breaking was caused by his effort to break it by swinging his arm down forcefully on it. That is why it would be a poor excuse for him to say to his wife “Chance did it (broke the table), not me.” Even though chance was causally relevant, because there was chance he would fail, chance didn’t do it, he did.

But isn’t it the case, one might ask, that whether one of these neural processes succeeds (say, in choosing A) rather than the competing process (in choosing B) (i) depends on whether certain neurons involved in the processing fire or do not fire (perhaps within a certain time frame); and isn’t it the case that (ii) whether or not these neurons fire is undetermined and hence a matter of chance and hence that (iii) the agent does not have control over whether or not they fire? But if these claims are true, it seems to follow that the choice merely “happened” as a result of these chance firings and so (iv) the agent did not make the choice of A rather than B and (v) hence was not responsible for making it. As a consequence, it looks like the outcome must be merely a matter of chance or luck and not a responsible choice after all.

But those who reason this way do so too hastily. For the surprising thing is that, even if (i)–(iii) are true, (iv) and (v) do not follow when the following conditions also hold: (a) the choosing of A rather than B (or B rather than A, whichever occurs) was something the agent was endeavoring or trying to bring about, (b) the indeterminism in the neuron firings was a hindrance or obstacle to the achievement of that goal and (c) the agent nonetheless succeeded in achieving the goal despite the hindering effects of the indeterminism.

For, consider the husband swinging his arm down on the table. It is also true in his case that (i) whether or not his endeavoring or trying to break the table succeeds “depends” on whether certain neurons in his arm fire or do not fire; and it is also true in his case that (ii) whether these neurons fire or not is undetermined and hence a matter of chance and hence (iii) their firing or not, is not under his control. Yet, even though we can say all this, it does not follow that (iv) the husband did not break the table and that (v) he is not responsible for breaking the table, if his endeavoring or trying to do so succeeds. Surprising indeed! But this is the kind of significant result one gets when indeterminism or chance plays an interfering or hindering role in larger goal-directed activities of agents that may succeed or fail.

It is well to reflect on this: We tend to reason that if an action (whether an overt action of breaking a table or a mental action of making a choice) depends on whether certain neurons fire or not (in the arm or in the brain), then the agent must be able to make those neurons fire or not, if the agent is to be responsible for the action. In other words, we think we have to crawl down to the place where the indeterminism originates (in the individual neurons) and make them go one way or the other. We think we have to become originators at the micro-level and “tip the balance” that chance leaves untipped, if we (and not chance) are to be responsible for the outcome. And we realize, of course, that we can’t do that. But we don’t have to. It is the wrong place to look. We don’t have to micro-manage our individual neurons to perform purposive actions and we do not have such micro-control over our neurons even when we perform ordinary actions such as swinging an arm down on a table.

What we need when we perform purposive activities, mental or physical, is macro-control of processes involving many neurons—processes that may succeed in achieving their goals despite indeterminacies that may be involved in “the naturally noisy processes of sensory transduction.” We do not micro-manage our actions by controlling each individual neuron or muscle that might be involved. But that does not prevent us from macro-managing our purposive activities (whether they be mental activities such as practical reasoning, or physical activities, such as arm-swingings) and being responsible when those purposive activities attain their goals, despite the indeterminacies involved. And this would be true in self-forming choices or SFAs, as conceived above, whichever of the competing purposive activities succeeds.

5 Further Issues: Efforts, Introspection, Agency, Control, Rationality

Needless to say, there are many further potential objections to the preceding view that need to be addressed, as with any view, and which I have tried to address in many of my writings. In this concluding section I can only briefly respond to a few of these additional objections and refer readers to other writings for discussion of others.Footnote 1

A commonly-made further objection is that it is irrational to make efforts to do incompatible things. I concede that in most ordinary situations it is. But I contend that there are special circumstances in which it is not irrational to make competing efforts: These include circumstances in which (i) we are deliberating between competing options; (ii) we intend to choose one or the other, but cannot choose both; (iii) we have powerful motives for wanting to choose each of the options for different and competing reasons; (iv) there is a consequent resistance in our will to either choice, so that (v) if either choice is to have a chance of being made, effort will have to be made to overcome the temptation to make the other choice; and most importantly, (vi) we want to give each choice a fighting chance of being made because the motives for each choice are important to us. The motives for each choice define in part what sort of person we are; and we would taking them lightly if we did not make an effort in their behalf. And, as it turns out, these are precisely the conditions of “self-forming” actions or SFAs (see e.g., Kane 1996, 128–143, 2002b, 417–124).

It is important to note in this connection that our normal intuitions about efforts are formed in everyday situations in which our will is already “settled” on doing something, where obstacles and resistance have to be overcome if we are to succeed in doing it. We want to open a drawer, which is jammed, so we have to make an effort to pull it open. In such everyday situations, it would be irrational to make incompatible efforts because our wills are already settled on doing what we are trying or endeavoring to do. But situations of the above kinds involving SFAs are what I call will-setting rather than will-settled. They are situations in which one’s will is not yet set on doing either of the things one is trying to do, but where one has strong reasons for doing each (e.g., deciding to A and deciding to B), and neither set of reasons is as yet decisive. Because most efforts in everyday life are made in will-settled situations, we tend to assimilate all effort-making to such situations, thereby failing to consider the uniqueness of will-setting, which is of a piece, in my view, with the uniqueness of free will.

Another commonly-made objection is that we are not introspectively or consciously aware of making dual efforts and performing multiple cognitive tasks in self-forming choice situations. But I am not claiming that agents are introspectively aware of making dual efforts. What persons are introspectively aware of in SFA situations is that they are trying to decide about which of two (or more) options to choose and that either choice is a difficult one because there are resistant motives pulling them in different directions that will have to be overcome, whichever choice is made. In such introspective conditions, I am theorizing that what is going on underneath is a kind of distributed processing in the brain that involves separate attempts or endeavorings to resolve competing cognitive tasks.

There is a larger point here that I have often emphasized: Introspective evidence cannot give us the whole story about free will. Stay on the introspective surface and libertarian free will is likely to appear obscure or mysterious, as it so often has in history. What is needed is a theory about what might be going on underneath when we exercise such a free will, not merely a description of what we immediately experience. In this regard, it is my view that new scientific ideas can be a help rather than a hindrance to making sense of free will.

It is now widely believed, for example, that parallel processing takes place in the brain in such cognitive phenomena as visual perception. The theory is that the brain separately processes different features of the visual scene, such as object and background, through distributed and parallel, though interacting, neural pathways or streams.Footnote 2 Suppose someone objected that we are not introspectively aware of such distributed processing in ordinary cases of perception. That would hardly be a decisive objection against this new theory of vision. For the claim is that this is what we are doing in visual perception, not necessarily that we are introspectively aware of doing it. And I am making a similar claim about free will. If parallel distributed processing takes place on the input side of the cognitive ledger (in perception), then why not consider that it also takes place on the output side (in practical reasoning, choice and action)? That is what I am suggesting we should suppose if we are to make sense of libertarian free will.

Another set of objections involves issues about control. Doesn’t indeterminism at least diminish the control agents exercise over their self-forming choices or SFA’s? Indeterminism does diminish a certain kind of control that agents may exercise over their self-forming choices, which I have called antecedent determining control, the power to guarantee or determine in advance that some event will occur. Clearly agents cannot have such control over SFAs (which are deliberative stits) and which must be undetermined at all times before they occur. But from the fact that one does not control which of a set of outcomes is going to occur before it occurs, it does not follow that one does not control which of them occurs when it occurs (Kane 1996, 133–148, 1999a). When the conditions for SFAs are satisfied, agents exercise control over their future lives then and there by deciding. Indeed, as argued earlier, they have what I have called “plural voluntary control” over their options in the sense that they are able at the moment of choice to bring about whichever of the options they will, when they will to do so, for the reasons they will to do so, and on purpose rather than by mistake or accident.

And note that it is the diminishment of antecedent determining control over any one of the options that makes possible such plural voluntary control over each of them. Indeterminism, by being a hindrance to the realization of some of the agent’s purposes, opens up the possibility of pursuing other purposes, of doing otherwise, voluntarily and rationally. To be genuinely self-forming agents (creators of ourselves), to have a free will, there must at times in life be such obstacles and hindrances in our wills that must be overcome. Self-formation, as I like to say, is not a gift, but a struggle.

One further remark about control: For an agent to have control generally at a time t over the being or not being (existence or non-existence) of some event (e.g. a choice) is for the agent to have the ability or power at the time t to make that event be at t and the ability or power to make it not be at t. And in an SFA, one exercises just such control over the choice one makes (e.g. the choice of A rather than B) at the time one makes it. For, one not only has the ability or power at that time to make that choice be, one also has the ability or power at that time to make it not be, by making the competing choice (of B rather than A) be. One has both these powers because either of the efforts or endeavorings in which one is engaged might succeed in attaining its goal (choosing A or choosing B) at the time. And if either effort does succeed in attaining its goal, the agent can be said to have brought about the choice thereby made by making that effort to bring it about.

A final objection I will consider here is this: Is there not some truth to the oft-repeated charge that undetermined choices of the kinds required by libertarian free will must be arbitrary in a certain sense? A residual arbitrariness seems to remain in all self-forming choices or SFAs since the agents cannot in principle have sufficient or overriding (“conclusive” or “decisive”) prior reasons for making one option and one set of reasons prevail over the other.

I think there is some truth to this charge, but it is a truth that reveals something important about free will. I have argued elsewhere (Kane 1996, 145–146) that such arbitariness relative to prior reasons tells us that every undetermined self-forming choice or SFA is the creation of novel constraints upon an agent’s pathway into the future, constraints that are not fully explained or determined by the agent’s past, but are consistent with that past. In making such a choice we say, in effect, “I am opting that these purposes and plans (rather than some others) will be a part of my pathway into the future, my future life. Doing so is not required by my past reasons, but is consistent with my past and represents one branching pathway my life can now meaningfully take. Whether it is the right choice, only time will tell. Meanwhile, I am willing to take responsibility for it one way or the other.”

Of special interest here, as I have often noted, is that the term “arbitrary” comes from the Latin arbitrium, which means “judgment”—as in liberum arbitrium voluntatis, “free judgment of the will,” which is the medieval designation for free will. Imagine a writer in the middle of a novel. The novel’s heroine faces a crisis and the writer has not yet developed her character in sufficient detail to say exactly how she will act. The author makes a “judgment” about this that is not determined by the heroine’s already formed past which does not give unique direction. In this sense, the judgment (arbitrium) of how she will react is “arbitrary,” but not entirely so. It had input from the heroine’s fictional past and in turn gave input to her projected future.

In a similar way, agents who exercise free will are both authors of and characters in their own stories at once. By virtue of “self-forming” judgments of the will (arbitria voluntatis) (SFAs), they are “arbiters” of their own lives, “making themselves” out of past that, if they are truly free, does not limit their future pathways to one. If we should charge them with not having sufficient or conclusive prior reasons for choosing as they did, they might reply: “True enough. But I did have good reasons for choosing as I did, which I’m willing to endorse and take responsibility for. If they were not sufficient or conclusive reasons, that’s because, like the heroine of the novel, I was not a fully formed person before I chose (and still am not, for that matter). Like the author of the novel, I am in the process of writing an unfinished story and forming an unfinished character who, in my case, is myself.”

In the logical framework of Belnap et al. Facing the Future, these libera arbitria voluntatis or self-forming choices (SFAs) would be deliberative stits, or deliberative seeings to it that, of agents. They are represented at moments in the logic of branching time at which there are multiple possible branching future histories; and they determine a particular class of possible future histories within which the future life of the agent must lie. Such self-forming actions or SFA’s are not the only kinds of actions that agents can perform “of their own free wills,” however, on the above account. As noted earlier, often we act from a will already formed, but it is “our own free will” (a will “of our own free making”) to the degree that we formed it by earlier SFAs that were undetermined, and for which we could have done otherwise voluntarily, intentionally and rationally.

Those acts that flow determinately from a will already formed in this manner could be counted as achievement stits in the framework of Facing the Future. And they too could be acts done “of our own free wills” to the degree that the wills from which they determinately flow were formed by earlier SFAs. For example, on my way to a class this afternoon on campus, I look up at the clock on the University tower and notice that it is five minutes before the start of the class. Without deliberating about it, I immediately hasten my pace in order to make the class on time. I did not make an explicit choice or decision to hasten my pace at that moment. My doing so was rather guaranteed once I noticed the time (in the manner of an achievement stit) by a prior choice (an SFA) made the day before, when I resolved not to be late for any more classes this semester. I thus hastened my pace “of my own free will” in the sense of a will freely formed in part by a prior self-forming choice (a deliberative stit) that was undetermined and such that I could have done otherwise when I made it.

In such ways, and in many others, the logical framework pioneered by Nuel Belnap and spelled out by him and his co-authors in Facing the Future provides, in my view, just the right kind of logical framework required to give an account of a traditional (libertarian) free will requiring indeterminism and thereby to answer what I have called the Intelligibility Question.

References

Bechtel, W. (ed.). 2001. Philosophy and the neurosciences: A reader. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Belnap, N., M. Perloff., and M. Xu. 2001. Facing the future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eccles, J. 1994. How the self controls the brain. Berlin: Springer.

Kane, Robert. 1985. Free will and values. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Kane, Robert. 1989. Two kinds of incompatibilism. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 31: 219–254.

Kane, Robert. 1996. The significance of free will. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kane, Robert. 1999a. Responsibility, luck, and chance: Reflections on free will and indeterminism. Journal of Philosophy 96: 217–240.

Kane, Robert. 1999b. On free will, responsibility and indeterminism: Responses to Clarke, Haji and Mele. Philosophical Explorations 2: 105–121.

Kane, Robert. 2000. Précis of The significance of free will and Responses to Bernard Berofsky, John Martin Fischer, and Galen Strawson. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 60(129–34): 157–167.

Kane, Robert (ed.). 2002a. The Oxford handbook of free will, 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kane, Robert. 2002b. Free will: New directions for an ancient problem. In R. Kane, ed. Free Will, 222–48. Oxford: Blackwell.

Kane, Robert. 2005. A contemporary introduction to free will. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kane, Robert. 2007. Libertarianism and Responses to Fischer, Pereboom and Vargas. In Four views of free will. Fischer, Kane, Pereboom, and Vargas, 5–43 and 166–83. Oxford: Wiley.

Kane, Robert. 2008. Three freedoms, free will, and self-formation: A reply to Levy and other critics. In Essays on free will and moral responsibility, ed. N. Trakakis, and D. Cohen, 142–161. Newcastle on Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Press.

Kane, Robert. 2009. Free will and the dialectic of selfhood. Ideas y Valories 58: 25–44.

Kane, Robert. 2011. Rethinking free will: New directions for an ancient problem. In The Oxford handbook of free will, 2nd ed, ed. R. Kane. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. 2002. Beyond good and evil. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Strawson, P.F. 1962. Freedom and resentment. Proceedings of the British Academy 48: 1–25.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

This chapter is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

Copyright information

© 2014 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kane, R. (2014). The Intelligibility Question for Free Will: Agency, Choice and Branching Time. In: Müller, T. (eds) Nuel Belnap on Indeterminism and Free Action. Outstanding Contributions to Logic, vol 2. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01754-9_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01754-9_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-01753-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-01754-9

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawPhilosophy and Religion (R0)