Abstract

Our society faces constant challenges as a result of how we continually shape our present and future. We do it by designing technologies, policies, laws, and whatever else makes up our lives. Unfortunately, the dialogue between people, disciplines, and cultures that could address these challenges is broken. Consequently, other means are used for resolving conflicts; they are seldom constructive, and they are occasionally devastating, war-like situations. By better understanding what design and its critical importance are, through a new comprehensive framework, we may be in a good position to design new transdisciplinary education programs that will improve people design and dialogue capabilities, making everybody equal partners in shaping our better future.

Design, if it is to be ecologically responsible and socially responsive, must be revolutionary and radical (going back to the roots) in the truest sense.

Victor Papanek, Design for the Real World (1971, p. 343).

The title has two meanings. The first meaning is as it is read: a call for us to design our future as we want it to be. The second meaning claims that the situation of designing is the future we want. Further, this title embeds the title of J. Fresco’s book, Designing the Future, The Venus Project, 2007, where he outlines his technological solutions to challenges and inviting others to participate in the design of their future.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

6.1 The Dialogues Are Broken

Are we happy about the situation around us? U.S. elections and their aftermath, Brexit, and elections coverage elsewhere in the world tell us that many people are looking for a change, and it is unclear that they or most others understand exactly the consequences of these changes. There is fear of terrorism and security problems; there are cultural clashes, old and new; and the old problems of hunger and inequality, and controversies on global warming still persist. Yet, some technology advocates tell us, and they are more insistent today, that technology has the solutions to all human challenges, that with technology, the future is better.Footnote 1 Abundance is better, much as economic growth has been a goal in itself for decades.

Some problems indeed are addressed by technology but others emerge. This cannot be a surprise as we already know from the behavior of complex systems that sometimes, even a seemingly trivial combination could lead to results that no one could forecast.Footnote 2 Consequently, such emergent behavior should be expected. When it has harmful effect, sometimes, it may be contained, but only if we detect it soon enough. Fast pace changes may be difficult or impossible to control and unfortunately, technology advocates tell us that progress is exponential.

The problem may also be in the concept of abundance we seem to strive for. WuFootnote 3 makes a compelling case against it from several perspectives. First, it leads to problems such as obesity and information overload, where the latter may counter the positive effects of the wealth of information and networks.Footnote 4 Second, this wealth leads people to lose their ability to exercise sensible judgment.Footnote 5 While scarcity makes people agile, fit, and even creative,Footnote 6 abundance may make them unfit. It becomes easy to use artifacts for serving political purposes or minority benefits rather than dealing with general humans’ betterment and the care of the environment.Footnote 7 Metaphorically, abundance seeks to get us back to the Garden of Eden but with it, perhaps undo the consequences of eating the apple: have whatever is offered to us and be dumb. Is this what we want?

It would have been great if we had clear knowledge about the consequence of our actions or what wrong could be done with the technology we develop. But as presented above, for each book that provides a compelling view with evidence about a situation, there may be another with a contradicting view. These views present models of the world, approximations that may reflect everything from reality to illusions.Footnote 8 They are well-argued opinions, but not truth. Shouldn’t these opinions engage in a dialogue to sort their differences?

We saw that technology solutions may not lead to benefiting all stakeholders and are not even considering all stakeholders desires initially. They also do not necessarily lead to democratizing decisions. This has been noticed years ago, and similarly, the case for broken dialogues and their consequences have been made before. There have been proposals to address this problem toward a more humanistic approach to social change through the design of our environment, our lives, and the way we govern ourselves.Footnote 9 These clarion calls while celebrated at times have fallen on deaf ears as they have not had their effect on our daily lives. When dialogues are broken, other means are been used to resolve conflicts. These means have become more vitriolic, rhetorical, and violent resulting in civil conflicts and wars.

The question for all interested in fixing the dialogue is whether such a fix is a lost cause or should we develop new models for the creation of healthy and productive dialogues. To understand the task ahead of us we need to understand why earlier ways of addressing this problem have failed? Why is it that we cannot mobilize the people to support such ideas? Was it because they challenge the political order? Is the public given “bread and circuses”Footnote 10 to divert its attention? Are we doomed to wait for a catastrophic dysfunction of the world with no hope for a change? Do we really have no free will?Footnote 11 How do we approach our goal of change given that there are revolutionary efforts that do come about and flourish in some corners of the world?

6.2 The Design Hypothesis

Everything around us other than nature has been designed, contemporary human problems alike. One may claim, following the complex system argument (see Footnote 3), that humanity’s challenges are accidents, emergent behavior out of past, and present unmanageable context. But given that they are not addressed seriously today, and that some people benefit from them, we can postulate that those who benefit exercise design to maintain the status quo. The design hypothesis contends that if there is a problem that persists, we should look for those who benefit from it and we will find out who designed the problem or is presently engaged in preventing its solution by further design. We exercise significant intention in our designing; otherwise, it would be quite difficult to explain huge coordinated efforts such as the Apollo Mission, the development of the F35 stealth fighter or the Large Hadron Collider at CERN. Until refuted, the pervasiveness of design as an activity that underlies the human condition is my working hypothesis.

With this hypothesis suggesting that humanity’s problems or their maintenance are driven by design, it becomes imperative to better understand the nature of this critical human skill—designing. As a first observation, if we argue that there are critical challenges facing humanity, it means that the act of design has not been conceptualized and exercised well by most of us. If we see around us inequality, it means that some people exercise their ability to design their future very well to their advantage compared to others. This behavior is not imaginary as has been noted in recent study that shows how the American upper middle class has managed to create space that more and more ensures their social and economic mobility at the cost of those who are in the lower economic classes.Footnote 12

It is not surprising that we would find diversity in designing skills; there will always be a distribution regarding any skill. However, the point is different; designing is a particular skill that is ignored in our educational systems, leading to destroying whatever design skills we are born with or acquire until kindergarten.Footnote 13 This deficiency creates a situation that most people lack design skills, creating an opportunity for others who maintain them or acquire them to be far ahead of others.

The first step is, therefore, educational, at all fronts, starting with young children; continuing to adults, and even professionals and researchers; and ending with the elderly. All these people face challenges or issues on a daily basis that require designing; they will all benefit from owning better design skills. To enlist them in an educational program, we need to improve their awareness of this critical human skill and the significant consequences of exercising it to our lives. Designing this educational project is outside the scope of this essay; its scope is explored elsewhere.Footnote 14 Here, I only describe briefly the status of the broken dialogue between disciplines and some attempts to fix it. I end with a framework about design called the PSI matrixFootnote 15 that helps put different disciplines and their interactions in perspective so that we can better understand what designing is, when it succeeds or fail, and subsequently, be able to design a better future.

6.3 Broken Multidisciplinary Dialogues

Let us go deeper to understand some causes of the broken dialogue and its extent. This could help us understand how to approach fixing it. Disciplines as we recognize them today have their roots in their formal study at higher education institutions. Take, for example, engineering that started as military engineering. In the nineteenth century, civil engineering and mining branched out as separate disciplines and toward the end of the nineteenth century, new disciplines emerged rapidly, chemical engineering, mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, material, agricultural, industrial, and others.Footnote 16 Each discipline started to concentrate on its own products, developed concepts, and models to deal with them, effectively specializing a language to converse among its members. It became difficult for professionals from different disciplines to effectively communicate.

As long as we stay within engineering disciplines, a fraction of these communication difficulties could be bridged by new theoretical developments,Footnote 17 simple visual languages that could form a common ground,Footnote 18 or lead to some advances in engineering education.Footnote 19 But the problem is much more profound. Throughout the twentieth century, engineering education in the different disciplines turned from stressing the practice or skills of the professions though forms of apprenticeship, to focus on theory and became engineering sciences. Engineering schools started to create people who knew the science in one niche area but little about the consequences, practical, technical, environmental, social or otherwise, of practicing their knowledge in the real world. From the master builders of the past, professionals became masters of siloed knowledge. This created professional engineers knowledgeable about some of the technical aspects needed for addressing challenges but often not even the ability to integrate knowledge within their own discipline and definitely ignorant of actual human needs and context. In a discipline such as economics, such educational practices led to people that are experts in the science of economics but do not know whether it is related to practice or real economics and may be uninterested in its consequences to issues such as sustainability. This situation, where there is no training in the synthesis of knowledge from different spheres, allows those in power to manage the present situation and even increase existing gaps such as between rich and poor.

Consider, for example, the development of technologies such as smart clothing or augmented reality. While they could be useful in many cases, they would constantly collect information about us in an unprecedented way. For example, there would be a timed record of where we look and how our heart beats in response. We could then be presented with filtered, summarized, and even manipulated informationFootnote 20 that would change how we feel,Footnote 21 inform us about what we see, who we should be weary of, and what we must buy on our way. While we are so occupied with this stream of information, catastrophic accidents may occur.Footnote 22 Since most of our information today comes from the Internet, influencing what we know and our opinions, it is clear that we could be easily manipulated by technology to the advantage of those controlling the information we consume. Yet, if we look around us, technology continues to be developed without thinking about its risks. Without serious dialogue between different disciplines, and given that different stakeholders have conflicting interests, power structures will determine our future trajectories as they have currently.

Broken dialogues have even a deeper impact because different stakeholders try to advance their own interests. Sometimes these interests get embedded in ideas that are attractive and have become common knowledge while they are in fact often misleading. For example, consider the following statements: (1) Science uncovers the truth about the world—this gives scientists distinguished status and scientific knowledge becomes superior to other forms of knowledge—a position that has been at least contested.Footnote 23 Further, if science uncovers the truth about the world, it does not change it and this relieves scientists from thinking about the consequences of their discoveries. (2) Democracy means equal rights for all citizens—but most times decisions are made based on the interests of powerful minorities.Footnote 24 (3) Law serves justice—this gives lawmakers and those who control them supreme power. A law designed to serve a powerful minority becomes inherently unjust, creating unbelievable anomalies such as the differences in the punishment for different crimes.Footnote 25 (4) Innovation leads to happiness—so why is there so much stress in society today?Footnote 26 In addition, why is innovation used to addict people to products they do not need or even harm them?Footnote 27 Finally, (5) globalization benefits everybody—but it turns out not to be this way for many workers in many countries.Footnote 28 We see how language creates powerful idioms, rather than truths, that serve the interests of those who advance them while precluding dialogue about their meaning. We see how controlling the language means power.

6.4 The PSI Matrix for Understanding Design

Broken dialogues lead to different interest groups maximizing their benefits, at best while ignoring others, but as indicated before, many times through exploiting others by design. Local maximizations by different groups will almost never lead to global optimum. This local–global (part-whole or self-community) distinction is a central concept in design. It permeates all aspects related to design including: (1) the spending on components vs. spending on their integration, (2) the needs of individuals vs. those of the community, (3) the personal skills vs. teamwork, or (4) focusing on a tool or a process vs. on organizational culture. Balancing this part-whole relation is key to designing. In order to design a better future, we need to understand better what is this designing skill that is at the heart of our problems and their solutions.

The PSI matrix is a framework that allows understanding designing and managing it toward success, where even what is considered as success is a product of the design process. The framework is borne out of understanding that even when we speak about designing; it is not a homogeneous endeavor. We need a transdisciplinary framework to understand it. Clearly, any framework about design should deal with at least the following questions:

-

1.

What is the problem or issue we are addressing by design?

-

2.

Who is involved in defining the problem and addressing it?

-

3.

How is the problem being addressed?

These seemingly simple questions embed some major complexities. For example, who is the “we” in the “what” question? How does this act bring together the people to form this “we”? How is the second question answered before knowing what is the “problem”? There are interdependencies between these questions and their answers, and it is unclear who has the responsibility, skills, methods and culture, and authority to address them. It is a situation where parts become wholes elsewhere and vice versa—it is a circular recursive situation.

The complexity goes even further as in order to answer the “what” question, knowledge from diverse disciplines is necessary including: engineering dealing with technology, sociology dealing with human needs or culture, and history dealing with the historical context embedding the problem. But there is hardly any dialogue between these disciplines.

To answer the “who” question, knowledge from at least psychology, sociology, and education is necessary to understand how people behave and work together even if they come from diverse backgrounds and cultures, what motivates them and how their capabilities and skills could be assessed and improved? To answer the “how” question, knowledge of management, economics, and even law must be exercised to create the working infrastructure that will enable all the activities required starting from problem identification, collection of participants, and infrastructure setup. Clearly, these disciplines hardly speak with each other and the recursive nature of design surfaces again.

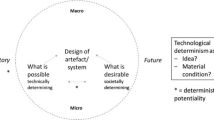

Figure 6.1 describes the PSI matrix (see Footnote 15). The bottom level is the level that describes the daily activities we have concentrated on thus far, consisting of three spaces: problem (P) space that characterizes what is the problem; social (S) space that characterizes who addresses it; and institutional (I) space that characterizes how it is addressed. When dialogues break (for example, due to conflicting interests), or do not exist (due to lack of common language), the lower level malfunctions. This may lead to one group maximizing its benefits at the expense of others because not everybody is included in the “who,” and the “how” creates an asymmetry of information flow. Malfunctioning of the lower level may also lead to wasting resources and creating solutions that are worse than the original problems.

In the case of such malfunctions, knowledge of design would tell us that a second level PSI is needed and constituted. Systems, companies, or even societies may have aspects of this level in the form of control systems, audit committees, or regulatory agencies, but again, we are forced to ask, what are the issues they address? who is involved, and how do they operate? We have at this level the same complexity we had at the first level PSI. The third and top level PSI needs to determine the vision, ethos, or “DNA” of the social system we are discussing, again with similar complexities of issues as the first two levels.

For a system, organization, or society to function well, all these levels, and the P’s, S’s, and I’s in them have to be aligned and balanced while interacting with each other between and across levels. Metaphorically, this resembles a tensegrity structure (Fig. 6.2) where the rods are the PSI matrix elements and the strings connect them into a system and balance them. If one rod is extended beyond proportion, representing a local maximization, the structure may fall apart. If all rods grow together, there is also a point where the strings break, suggesting that growth need to be accompanied by a structural change. Furthermore, some configurations with specific rod sizes may be singular. It is interesting to note that controlling the movements of such structure and checking its singular positions is complexFootnote 29; consequently, projecting such issues onto complex systems, organizations, or societies may be overwhelming.

At this point, it is clear that even a parsimonious framework for understanding design, like the PSI matrix is very complex and even could be fragile. We can use the framework to understand how design situations could break or be used wrongly by some. We could use the framework to guide us from a particular state in these spaces to a desired state.

6.5 Epilog

Our reality is the result of design activities. We can only understand how we arrived at the present situation and move forward if we understand that the answer starts by improving the design capabilities of people or of society. We can only achieve this if we stir the course of education from disciplinary specialization at the least with some minimal inter or multidisciplinary collaboration, to truly create new languages and culture for transdisciplinary endeavors. For education to respond to all its levels this creates a serious challenge but there seems not to be any other way.

The design hypothesis and the PSI framework provide a first glance at what we need to study, further develop, and teach. It is outside the scope of this essay to go deeper into the framework’s upper levels or attempt an explanation of why previous attempts at addressing the broken dialogue have failed. Analysis of different contexts such as organizational failures have been done (see Footnotes 14 and 15) and continue to be explored,Footnote 30 but in general, they are complex because they need a dialogue between numerous experts in diverse disciplines that are related to the PSI as were indicated before. The purpose of this essay was to raise the issue of broken dialogue again; to propose that design is at the heart of understanding past failures and present causes of difficulties; and to make the case that design offers the opportunity to design a better future. This requires that we educate people about it, become more aware of who tries to exploit it, understand how we can fail and be cautious and proactive about it, and engage in a collective dialogue about the role design plays in our daily individual and social lives.

Notes

- 1.

Diamandis and Kotler (2012).

- 2.

- 3.

Wu (2013).

- 4.

Benkler (2006).

- 5.

Tierney and Baumeister (2011).

- 6.

A great example of creativity and skills turning barrels into stoves https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JBOF0OTPUrs.

- 7.

- 8.

Such models can be created intentionally, by design, to serve the opinion proposed. It would be justified as following the scientific method where, for example, physical phenomena are removed from their context to be studied in the lab. However, in our case, the issues we discuss cannot be isolated from their context.

- 9.

- 10.

Satire X by Juvenal.

- 11.

Sapolsky (2017). Sapolsky makes a case that our behavior is determined by our biology and that the reason we are unable to predict or explain fully certain behaviors is our lack of knowledge of the multifactorial relation between biology and behavior. This view is in complete contradiction to the design view proposed here but its present status is just a hypothesis.

- 12.

Reeves (2017).

- 13.

Refer to Ken Robinson’ TED lecture, Do Schools Kill Creativity? for a popular articulation of this subject https://www.ted.com/talks/ken_robinson_says_schools_kill_creativity.

- 14.

E. Subrahmanian, Y. Reich, S. Krishnan, We The Designers, submitted.

- 15.

- 16.

Tadmor (2006).

- 17.

Such as the Interdisciplinary Engineering Knowledge Genome (IEKG) that attempts to create a bridge between different disciplines through a network of mathematical representations, Reich and Shai (2012).

- 18.

Such as visual languages in Quality Function Deployment that could allow project managers and systems engineers as well as production line workers to converse and exchange vital knowledge, Akao (1990).

- 19.

Crawley et al. (2007).

- 20.

Consider the recent ruling of the European Community against Google for manipulating its search engine results to gain advantage over its competitors. Google was fined for 2.42 B€. https://youtu.be/9cYeNpETjyw. The ability to do so through information accumulation and its further discussed in Zuboff (2015). Another way to distort information for negative purposes is available by social bots: Ferrara et al. (2016).

- 21.

See, for example, Kramer et al. (2014). Note the significant controversy about this study concerning its unethical status, not informing participants about their participation in the experiment, and the avoidance of Cornell University and PNAS journal editors to take responsibility for not checking it and publishing it in this way. Note also that the effect reported in this study is almost negligible but the sample size is so big that even such slim difference ends up being significant. Finally, since the first author is a Facebook employee comments on the web suggested that this paper will now allow Facebook to increase in advertisement fees given the impact that now could be associated with its information.

- 22.

Richtel (2014).

- 23.

Sarewitz (2016).

- 24.

Gilens and Page (2014).

- 25.

For example, California “three strikes” sentencing law as enacted in 1994, allowed punishing for food theft up to life sentence with documented people who got this punishment (e.g., http://www.sfgate.com/news/article/Stealing-one-slice-of-pizza-results-in-life-3150629.php or http://thegrio.com/2010/08/18/homeless-man-free-after-13-years-in-jail-for-stealing-food/); the law was amended in 2012 to make it less harsh, http://www.courts.ca.gov/20142.htm. In contrast, only one Wall Street executive was prosecuted and sent to 30 months in jail after the 2008 economic crises despite clear violations of the law. While this might not be a conspiracy to avoid procession, it may be a result of lack of knowledge or skills to deal with white-collar crimes that reflects priorities to invest resources in different aspects of the justice department, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/04/magazine/only-one-top-banker-jail-financial-crisis.html. Even the almost $190B fines and settlements paid by financial institutions following the crisis were shareholders money and not the executives themselves. The CEO of JP Morgan Chase even got a huge raise after closing the settlement of the bank. Other key bankers involved in the crisis received government positions in the Obama administration. All these reflect interests, power, but nothing resembling justice.

- 26.

Thielking (2017).

- 27.

A good example is the gambling industry that addicts gambler by design, Schüll (2014). Other examples include all “proper” designed websites or apps whose top goal is to keep people on their page as much as possible.

- 28.

Goldsmith and Mander (1997).

- 29.

- 30.

One present study uses the PSI matrix to understand why different projects of creating sustainable communities in Israel succeeded or failed.

References

Akao, Y. (1990). Quality function deployment: Integrating customer requirements into product design, (G. H Mazur, Trans.). Cambridge: Productivity Press.

Benkler, Y. (2006). Wealth of networks: How social production transforms markets and freedom. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Cahan, D., & Shai, O. (2015). Combinatorial method for checking stability in tensegrity structures. In ASME Design Engineering Technical Conferences, August 2–5, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, 2015.

Crawley, E., Malmqvist, J., Östlund, S., & Brodeur, D. (2007). Rethinking engineering education, The CDIO Approach. Berlin: Springer.

Diamandis, P. H., & Kotler, S. (2012). Abundance: The future is better than you think. New York, NY: Free Press.

Ferrara, E., Varol, O., Davis, C., Menczer, F., & Flammini, A. (2016). The rise of social bots. Communications of the ACM, 59(7), 96–104.

Fuller, B. (1960). World game. https://www.bfi.org/about-fuller/big-ideas/world-game.

Gilens, M., & Page, B. I. (2014). Testing theories of American politics: Elites, interest groups, and average citizens. Perspectives on Politics, 12(3), 564–581.

Goldsmith, E., & Mander, J. (1997). The case against the global economy and for a turn towards the local. California: Sierra Club Books.

Kramer, A. D., Guillory, J. E., & Hancock, J. T. (2014). Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(24), 8788–8790.

Orki, O., Ayali, A., Shai, O., & Ben-Hanan, U. (2012). Modeling of caterpillar crawl using novel tensegrity structures. Bioinspiration and Biomimetics, 7(4), L 046006.

Papanek, V. (1971). Design for the real world: Human ecology and social change. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Perrow, C. (1984). Normal accidents: Living with high risk technologies. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Reeves, R. V. (2017). Dream hoarders: How the American upper middle class is leaving everyone else in the dust, why that is a problem, and what to do about it. Massachusetts: Brookings Institution Press.

Reich, Y., & Shai, O. (2012). The Interdisciplinary Engineering Knowledge Genome. Research in Engineering Design, 23(3), 251–264.

Reich, Y., & Subrahmanian, E. (2015). Designing PSI: An introduction to the PSI framework. In Proceedings International Conference on Engineering Design, ICED’15, Milan, Italy, 2015.

Reich, Y., & Subrahmanian, E. (2017). The PSI Matrix—A Framework and a Theory of Design, ICED’17, Vancouver, Canada.

Richtel, M. (2014). A deadly wandering: A tale of tragedy and redemption in the age of attention. New York, NY: William Morrow.

Sapolsky, R. M. (2017). Behave: The biology of humans at our best and worst. London: Penguin Books.

Sarewitz, D. (2016). Saving science—The New Atlantis (pp. 4–40). Berlin: Spring.

Schüll, N. D. (2014). Addiction by design: Machine gambling in Las Vegas. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Slavutin, M., Sheffer, A., Shai, O., & Reich, Y. (2018). A Complete Geometric Singular Characterization of the 6/6 Stewart Platform. Journal of Mechanisms and Robotics.

Tadmor, Z. (2006). Redefining engineering disciplines for the twenty-first century. The Bridge, 36(2), 33–37.

Thielking, M. (Feb 6, 2017). A dangerous wait: Colleges can’t meet soaring student needs for mental health care, STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2017/02/06/mental-health-college-students/.

Tierney, T., & Baumeister, R. (2011). Willpower: Rediscovering the greatest human strength. London: Penguin Books.

Winner, L. (1980). Do artifacts have politics? Daedalus, 109(1), 121–136.

Wolfram, S. (2002). A new kind of science (Vol. 5). Champaign, IL: Wolfram Media.

Wu, T. (2013). The case for less: Is abundance really the solution to our problems? New Republic, April 23. 2013. Retrieved April 1, 2017, from https://newrepublic.com/article/112858/abundance-really-solution-our-problems.

Zuboff, S. (2015). Big other: Surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization. Journal of Information Technology, 30(1), 75–89.

Acknowledgements

I thank my long-term friend and colleague Eswaran Subrahmanian for inviting me to the NSF-ESI Workshop at Carnegie Mellon University, for our almost daily discussions from which the material presented in this essay emerged, and for his comments on a draft of this essay.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Reich, Y. (2018). Designing the Future We Want. In: Subrahmanian, E., Odumosu, T., Tsao, J. (eds) Engineering a Better Future. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91134-2_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91134-2_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-91133-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-91134-2

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)