Abstract

This chapter intends to present a practical approach to strategically facilitating sustainable, low-carbon transformation. The recommendations that can be made are presented while using a Weberian understanding (Verstehen) of various variables and dynamics that has been crystalized through this book’s theoretical foundation (chapters 2 to 6), methodological tools (chapters 7 and 8), case studies (chapters 9 to 12), simulation game (part of chapter 12), and the theoretical claims through the conceptual framework (chapter 13). A major contribution of this book is a set of recommendations that aim to support an inquiry-based, reflective, collaborative, and integrative facilitation of the transformation process.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

This chapter intends to present a practical approach to strategically facilitating sustainable, low-carbon transformation. The recommendations that can be made are presented while using a Weberian understanding (Verstehen) of various variables and dynamics that has been crystalized through this book’s theoretical foundation (chapters 2 to 6), methodological tools (chapters 7 and 8), case studies (chapters 9 to 12), simulation game (part of chapter 12), and the theoretical claims through the conceptual framework (chapter 13). A major contribution of this book is a set of recommendations that aim to support an inquiry-based, reflective, collaborative, and integrative facilitation of the transformation process. Reflexivity is itself a form of intervention that allows systems to adapt while preventing ruptures. An analysis of reflexivity can help better structure institutional, functional, and bargaining interactions from the negotiative perspective on context, agencies, and audiences of transformation towards sustainability. Reflexivity analysis is a matrix or collection of concrete questions that resonate at the (meta-level) theoretical/conceptual, methodological, and practical challenges relevant for each analytical level (actors, issues, structures, processes, and outcomes).

Serving as a roadmap, the stakeholder engagement plan is furthermore introduced in this chapter. As a practical example of application the engagement plan, this chapter looks at the transformation of the transport sector towards sustainability in Germany. The matrix is a decision tool that equates the typical ‘hypothetical’ analysis in legal studies. Hypothetical analysis pertains to the use of fictional but still realistic and feasible accounts when analyzing the potential actions of protagonists. The matrix demonstrates, for example, how narratives are tailored to make points without being burdened by doubts about the incompleteness of information. Hypothetical accounts can answer some questions that are unanswered by real-life case studies, because these accounts, including motivations and interactions, are described in an imaginary fashion (Green 2000 p. 991). Fictional vignettes may be useful to help identify situations where particular rules may apply and explore the ambiguity of rules (Green 2000 p. 995). Finally, unlike real-life case studies, hypothetical accounts can recognize the sensitivity of decision-making towards moral nuances and complexity.

14.1 Reflexivity Analysis—Developing Perspectives for Stakeholders’ Engagement

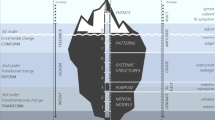

The reflexivity analysis of the multi-level and polycentric sustainable, low-carbon transformation towards sustainability can be conducted using the five different analytical levels (actors, issues, structures, processes, and outcomes). The use of these levels highlights the systems analytical approach. For this purpose, concrete questions and elaborating questions are formulated to help identify the conceptual (theoretical), methodological, and practical issues that need to be addressed when facilitating the transformation process. The questions summarize the insights and impulses gained from the previous chapters. The theoretical assumptions, knowledge tools such as theoretical models (ideal types), case studies, simulation, as well as the conceptual framework have not only contributed to the meta-level conceptual understanding of sustainable, low-carbon transformation and to explaining complex issues and dynamics, they have also identified methodological and practical issues that should be concretized and elaborated when facilitating sustainable, low-carbon transformation. These questions constitute the strategic approach that needs to be pursued by each stakeholder when preparing their strategies and when participating in various functional, institutional, and bargaining interactions (Table 14.1).

14.2 The Stakeholder Matrix and Engagement Plan

The insights and lessons gained from the theoretical, methodological, and empirical chapters of this book are used to come up with a stakeholder matrix and engagement plan that can help decision-makers structure their strategies and adapt to the various dilemmas and self-driving dynamics when making important decisions. The previous section empowers stakeholders to understand the questions that need to be asked to “master” the transformation process towards sustainability. The identification of meta-level theoretical, methodological, and practical issues allows integrated and systems analytical thinking that promotes the expansion of values. This expansion of values promotes collective decision-making by highlighting the ‘positive sum’ character of the transformation process.

The following figure illustrates an empty template of a matrix that summarizes and applies the outputs of all the chapters of this book. The stakeholders are first categorized according to their role in the policy-making process. Tier 1 are the direct agents that directly come up with policy instruments that could promote or inhibit transformation towards sustainability. Tier 2 refers to context-related policy entrepreneurs that include both enablers and spoilers which are not directly involved in policy-making but can enable or hinder (delay or obstruct) decision-making. Tier 3 (audience) pertains to entities that bestow different types of legitimacy on the transformation process through their direct or indirect approval or disapproval not only of the whole transformation process, but also of different (sub)processes (Table 14.2).

The different aspects of the matrix include the system and process-related role of these stakeholders, conflict analysis (how these stakeholders define conflict and how they see this conflict being resolved), and the type of engagement that can be utilized to produce specific outputs from this engagement. In addition, the matrix highlights the entry points to transformation towards sustainability, the caveats to support this transformation process, as well as the possible positions of stakeholders for further actions (which type of actions are most likely to be pursued).

To demonstrate the use of the matrix, a preliminary draft of the stakeholder analysis and engagement plan for the transformation process towards sustainability of the German transport sector (Verkehrswende) will be introduced. Some impulses were taken from current discussions among relevant stakeholders participating in various public discourses on sustainable transport in Germany. The draft suggests, for instance, how asking appropriate reflexive questions can explain why some stakeholders are ambivalent to sustainable transport. This highlights why one stakeholder or even a policy-making agent produces a series of actions that are contradictory. This is not necessarily an argument for the unpredictability or irrationality of this actor, but rather suggests existing entry points and caveats or barriers.

The Tier 1 agents refer to the different relevant government bodies as stipulated by the federal system, as well as Germany’s membership in the European Union. While the federal ministries tend to be the major agenda-setting actors in the negotiation process, the state governments (Bundesländer) employ other venues of participation. The city governments and local councils (Gemeinde) are also involved through various means and are considered the policy-makers nearest to the citizens. The Tier 2 agents are the policy entrepreneurs who have varying degrees of influence over Tier 1 agents. They also contribute different types of inputs that allow Tier 1 agents to efficiently address certain issues while maintaining legitimacy. They include the different “advisory councils” (Beiräte) such as the Deutsches Ethikrat (German Ethic Council), the Rat für nachhaltige Entwicklung (Advisory Council for Sustainable Development), the Sachverständigenrat zur Begutachtung der gesamtwirtschaftlichen Entwicklung (Advisory Council of Evaluators for the Evaluation of Total Economic Development) and the Wissenschaftlicher Beirat für globale Umweltveränderung (the Scientific Advisory Council for Global Environmental Change). These councils have become important pillars of policy-making in Germany. Other Tier 2 agents include research institutions, businesses and industry agents (either individually or as proponents of Verbände (associations)), the public transportation sector (represented by either individual entities or by associations) and labor unions. Foundations are considered Tier 2 agents, because they influence power relations between Tier 2 agents through their capacity-building activities. The media is considered here as a policy entrepreneur, because it often pursues its own interests, such as the accountability of policy-makers and the capacity-building of other policy entrepreneurs, and even of the audience by providing information. Political parties have been categorized as Tier 2 agents. Although they set the pace and direction of government policies and are often even political parties building the government or its coalition, as the German political party culture demonstrates, they can pursue other interests. In addition, government ministries can pursue policies that are the results of compromises with coalition partners, which can be unacceptable to the political base of the party. Furthermore, groups within a political party that control different levels (federal, state and local) may pursue contradictory views. Moreover, referring back to the “the efficient” and “the dignified”-dichotomy presented in the previous chapters, in this context, Tier 1 represents the “efficient” while Tier 2 the “dignified.” Finally, Tier 3 refers to the different audiences that assess the interplay between the efficient and the dignified. It includes the German audience, the EU audience, the global audience, as well as the distinct constituents of Tier 2 agents.

The matrix also demonstrates the system and process roles of Tier 1 and Tier 2 agents in the transformation process towards sustainable transport. While some agents can either push for change (change agents), others are more interested in ensuring stability by minimizing change (status quo agents). For example, the transportation ministry can be regarded as a change agent. Responding to structural changes in the transport sector, which may include new technological innovation that favors the sustainable development of the sector, it sets the agenda for different negotiations with other Tier 1 agents. Other Tier 1 agents, such as the Finance Ministry, may be keen on ensuring that the propositions of the change agents will not undermine the fiscal health of the country, thus initially acting as a brake to changes, at least until uncertainties about the future costs of transformation can be calculated and managed. In addition, some agents can be both a change and a status quo agent due to the complexity of the issues involved, where in some issues they seek change and in some they resist. For example, the Ministry of Economy and Energy can both push and pull the process depending on the issues involved. This might be initially seen as contradictory or even irrational behavior on behalf of the agent. In this situation, this ministry is dependent on how issues can be decoupled. For example, the Ministry of Economy and Energy on the one hand limit the pace of fuel switch from diesel to electric cars to protect the German car industry (pull), but on the other hand implement policy instruments to unlock carbon lock-ins in the car industry (push).

Moreover, the process roles of the agents refer to how each agent from every tier can contribute or inhibit the transformation process. For example, scientific communities as Tier 2 agents can provide inputs for evidence-based decision-making that ensure the effectiveness of transport policies and thus the legitimacy of relevant procedures. Other agents, such as the car industry, can be learners in the process, which, once persuaded through interactions with other agents, will be important game changers in the process. Scientific communities and think tanks can accelerate this learning process through partnerships and networks. Agents such as foundations and think tanks are relevant to the process, as providers of resources and proponents of capacity-building. They can, for example, increase funding to universities and research institutions that focus on public acceptance of public transportation systems.

The power base identifies the different sources of leverage for each agent. Some agents, through their access to expert knowledge, depend on procedural power to pursue their interests when interacting with the others. For example, the credibility of the Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development vis-à-vis foreign partners is defined by the know-how it can provide to other countries. Few agents can employ leverage through negative power, which can successful increase the costs and efforts needed to implement certain policies. For example, individual federal states (Bundesländer) can decide to block bills proposed by the federal government irrespective of their political party affiliations. Citizen groups that believe that building new train stations in their communities could attract criminals, drug addicts, and “cheap” tourism have different ways of blocking decisions or increasing the costs of implementing projects.

The negotiation analysis refers to the interests and anticipated negotiation style of agents when engaging in various levels of bargaining. The interests reflect the social mandate of these agents. Understanding these interests promotes flexibility and creativity in forging agreements. For example, in understanding that consumer protection will most likely be in the interests of the Ministry on Justice and Consumer Protection when it comes to sustainable transport, other agents wishing to achieve its support will need to include proposed stipulations ensuring consumer protection. Other interests of this ministry may include ensuring security and safety in transit infrastructures. Moreover, agents are anticipated to employ specific negotiation styles, which often depends on the agents’ role in the transformation process. For example, the European Commission might be highly competitive in the process to compensate for its position of merely responding or reacting to decisions made in Berlin (or Bonn). Other agents, such as federal state governments and local governments that employ negative power, will very likely be competitive in negotiating with the federal government, because veto power has the initial logic of preventing something. Agents such as the Ministry of Economy and Energy may tend to employ an avoidant negotiation style, because of its ambivalence to sustainable transport. With uncertainty, these actors will very likely be trapped in an indecisiveness dilemma. Thus, they will very likely avoid agreeing to much-needed, immediate commitments.

The conflict analysis pertains to the definition of conflict cleavages or the threshold where confrontation becomes more acceptable or desirable than inhibition. The conflict can refer to issues, processes, and procedures. In addition, conflict analysis summarizes each agent’s understanding of viable methods to achieve resolution of conflicts. For example, labor groups may see the conflict as resulting from inequitable procedures due to hierarchical relationships in the context of mutual dependence. For these labor groups, resolving procedural inequities will very likely employ context-sensitive approaches and will specifically target compensatory mechanisms for specific imbalances. The Federal Ministry of Employment and Social Affairs may see the conflict arising because of unclear jurisdictions, which can be resolved through deductive approaches through which acceptable principles are initially achieved, and then applying these principles to concrete issues. For example, this Ministry will very likely focus first on reconciling workers’ rights for employees of both the public transport sector and the car industry to the principles of sustainable transport.

‘Engagement’ refers to the ways in which agents can be mobilized in a process from the perspective of Tier 1 agents. Engagement is highly differentiated, depending on their role and their potential inputs into the transformation process. Tier 1 agents can empower, collaborate, consult, involve, or inform Tier 2 agents. For example, Tier 1 agents may choose to collaborate with selected Tier 2 agents such as scientific communities and think tanks. These selected agents can provide policy briefs and policy recommendations during consultations, or even appoint Tier 2 representatives to various expert committees. Others Tier 2 agents can be empowered through capacity-building measures (e.g., funding, access to information), because the fulfilment of their interests is to the benefit of Tier 1 agents. This empowerment can vindicate the social mandate of Tier 2 agents and help reinforce their identities as policy entrepreneurs are eventually able to reciprocate, which further legitimizes the process.

Tier 1 agents might also decide to limit or prevent the participation of certain Tier 2 agents due to a number of political and logistical reasons. These Tier 2 agents are merely informed. Nevertheless, those policy entrepreneurs who are merely informed will very likely still seek other means of influencing Tier 1 agents, depending on the capacity and autonomy of state institutions—from producing position papers to mobilizing street protests and boycotts through the media. Some will seek to influence public opinion and deliver sociolinguistic narratives to the audience which might be successful in gaining the attention of Tier 1 agents. For example, the Stuttgart 21 movement in Germany targeted the German railway corporation (Deutsche Bahn), leading not only to a loss for the Christian Democratic Union (CDU)-led conservative state government in Baden-Württemberg, but also to the massive increase in the costs of re-building the central station in the city of Stuttgart. The costs increased from 4 billion euros to 9 billion euros due to delays and additional provisions stipulated by later court orders that were successfully demanded by citizen groups. The Stuttgart 21 case proves that public acceptance can be a huge barrier in pursuing the Verkehrswende.

Entry points to transformation towards sustainable transport reflect the opportunities for each agent during and after the transformation process. These entry points may result from positive externalities, co-benefits and synergies. Some entry points are purposive, and others are emergent. Purposive entry points refer to benefits for each agent from additional measures to support sustainable transport that are in anyway planned to achieve other developmental goals. For example, the German Environmental Ministry (BMU) seeks to mitigate climate change through emission reduction. Because Verkehrswende seeks to decouple transport emissions from GDP growth, the BMU will most likely be motivated to support the Verkehrswende. Another example is the Ministry of Finance (BMF), which will most likely support the introduction of new taxes, such as fuel taxation and carbon pricing, needed to implement the Verkehrswende, because these new taxes could help the BMF maintain the fiscal health of the government. Emergent entry points are the direct, positive effects of sustainable transport that could motivate the support of agents. For example, the expectation that the Verkehrswende will very likely lead to the reduction of massive public investment in road infrastructure construction and maintenance will persuade the BMF to support the Verkehrswende.

Caveats to support transformation are the reasons behind the agent’s reluctance or opposition to sustainable transport. Most caveats refer to perceived future disadvantages as direct results of redistribution, double contingencies, political risks or even redundancy. For example, because of the redistribution for the EU Community (as an audience), the German Verkehrswende might further constrain EU wide electricity transmission lines, as well as put vehicles from other EU countries transiting in Germany in a disadvantageous position should fees for road use be introduced on German highways to motivate the use of public transportation (redistribution). As an example of double contingencies, the Media as a Tier 2 agent might be confronted with additional uncertainties and credibility problems due to its lack of technical expertise in issues relevant to Verkehrswende. Political parties might estimate the political risks of the Verkehrswende and refrain from pursuing unpopular measures such as the introduction of road use fees or the increase of a car tax and of a speed limit on all parts of the German Autobahn. In addition, private households might be indifferent to the sentiments of other private households in other areas directly affected by the construction of necessary infrastructure, the limitation of parking spaces, or the closure of city centers to car use. They are, in this case, essentially redundant and will most likely be supportive when they have direct benefits or be adversarial when personally confronted by negative effects (the ‘not-in-my-backyard, but yes if in the backyard of the others’ mentality).

Positions for further actions are demanded of agents to materialize their purpose as the transformation process unfolds. These positions have direct implications for the various levels of functional, institutional, and bargaining interactions. Some positions will call for more generic outcomes, which might enable different understandings of guiding principles and formulas. For example, some agents will look at the impact of the Verkehrswende on the egalitarian public space. Will the Verkehrswende promote interactions between citizens from different backgrounds or will it further reinforce segregation? Policy-makers will need to revisit and, if necessary, modify the compatibility of the principles of the Verkehrswende to those existing local narratives that frame principles. Will the construction of new rail networks be compatible with local identities (and traditions), particularly when gentrification through suburbanization arises? Will the increased property value and accessibility of real estate eventually drive out vulnerable, poor households?

Other positions may call for more time and flexibility to find technical solutions within the problem frame. For example, creating more opportunities for interdisciplinarity and systems thinking might allow the improvement of the intermittency problems of renewable energies that are significant for electric and hybrid cars. In addition, improving access to modern forms of transportation depends on income levels and income distribution. However, levels of income are also dependent on access to affordable and reliable transportation technologies. This ‘vicious cycle’ reiterates the limitations of technical solutions. Therefore, technology-driven policies need to work in concert with other development policies such as employment, income, institutional structures, social objectives, environmental integrity, and regional or local development.

Some positions might demand the targeting of the development of relations and communication channels, while others may focus on policy and bargaining games. Dialogue processes have wide applicability in Verkehrswende. Not only can they support the maturity of relevant technologies through provider-user support systems, they can also enhance input and output legitimacy. Through mechanisms for feedback and flexibility in programs and projects, dialogue becomes an investment and not a cost. The establishment of networks and cooperation bodies can help create and maintain various centers of excellence as spaces for knowledge-sharing on different issues that cut across policy priorities.

As a disclaimer, the example of the matrix and stakeholder engagement plan for the German Verkehrswende is, to date, merely conceptual, but still useful in many ways. While assumptions of the profiles of the stakeholders were made based on interpretations of the existing literature and on anecdotal analysis, there are still open issues that require further research. Nevertheless, it demonstrates how emerging coordination and collaboration problems, as well as planning issues can be anticipated. In addition, it identifies the areas of the German Verkehrswende that may not yet be fully understood (Table 14.3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hernandez, A.M. (2021). Lessons for Practice: Reflexivity and Stakeholder Engagement for Transformations Towards Sustainability. In: Taming the Big Green Elephant. Globale Gesellschaft und internationale Beziehungen. Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-31821-5_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-31821-5_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer VS, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN: 978-3-658-31820-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-658-31821-5

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)