Abstract

Offering a critical synthesis of extant insights into technological developments in AI and their potential ramifications for international relations and deterrence postures, this chapter argues that AI risks influencing military deterrence and coercion in unique ways: it may alter cost-benefit calculations by removing the fog of war, by superficially imposing rationality on political decisions, and by diminishing the human cost of military engagement. It may recalibrate the balance between offensive and defensive measures, tipping the scales in favour of pre-emption, and undermine existing assumptions imbedded in both conventional and nuclear deterrence. AI might altogether remove human emotions and eliminate other biological limitations from the practice of coercion. It may provide users the ability to collect, synthesize, and act upon real-time intelligence from several disparate sources, augmenting the certainty and severity of punishment strategies, both in theatre and online, compressing the distance between intelligence, political decisions, and coercive action. As a result, AI may quicken the overall pace of action across all domains of coercion, in conflict, crisis, and war, and within the related subfields of national security, counterterrorism, counter-crime, and counter-espionage.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is influencing national defence in several important ways. It alters the way states plan and conduct military engagements, collect and use intelligence, and protect their domestic national security. Traditional notions of state power are also increasingly intertwined with national expertise and investment in AI; an arms race is thought to be developing between the United States and China as a result. And in some states, private sector AI research is increasingly pitted against the defence sector’s interest in integrating AI into national security; ethical considerations abound. Despite these developments, researchers have yet to fully explore the way AI intersects with deterrence. The academic literature on the subject is particularly slim; very few studies have yet to unpack the various ways in which the technology might intersect with deterrence logic, theory, and practice writ large.Footnote 1 The dearth of knowledge is surprising given the expectation that the future of defence will likely be autonomous.Footnote 2 As this chapter will show, AI risks influencing military deterrence and coercion in unique ways: it may alter cost-benefit calculations by removing the fog of war, by superficially imposing rationality on political decisions, and by diminishing the human cost of military engagement. It may recalibrate the balance between offensive and defensive measures, tipping the scales in favour of pre-emption, and undermine existing assumptions imbedded in both conventional and nuclear deterrence. AI might altogether remove human emotions and eliminate other biological limitations from the practice of coercion. It may provide users the ability to collect, synthesize, and act upon real-time intelligence from several disparate sources, augmenting the certainty and severity of punishment strategies, both in theatre and online, compressing the distance between intelligence, political decisions, and coercive action. As a result, AI may quicken the overall pace of action across all domains of coercion, in conflict, crisis, and war, and within the related subfields of national security, cybersecurity, counterterrorism, counter-crime, and counter-espionage.

This chapter is an exercise in structured speculation: given what we know about the current state of the technology underpinning artificial intelligence and machine learning, and related innovations, what does the future of deterrence in the 21st century look like?Footnote 3 How will the use of AI in military and strategic affairs, counterterrorism, intelligence, and national security alter the way states practice deterrence? The chapter builds on Professor Wilner’s previous research on updating deterrence theory for non-traditional threats,Footnote 4 but is also largely derived from the authors’ ongoing research program on AI Deterrence.Footnote 5 The larger goal of the AI Deterrence project is to provide a systematic theoretical and empirical overview of how AI influences the practice of coercion, deterrence, compellence, denial, and influence across various domains, both in physical and cyber space, and across the disciplines (e.g. Criminology, IR, Terrorism and Intelligence Studies). The purpose of this chapter is more narrowly focused on exploring the way AI might intersect with interstate military deterrence and coercion more specifically. The chapter unfolds in six sections. Sections one to five explore several different ways in which AI and deterrence intersect, with specific discussions on hyper-war and hyper-coercion, scientific development and commercialization, autonomous weapons systems and tactical innovation, ethical constraints and asymmetries, and coercive credibility. The concluding section suggests avenues for further research on developing and empirically testing AI deterrence theory.

2 The Promises and Pitfalls of Hyper-Coercion

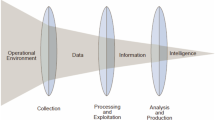

AI will shorten the distance from intelligence gathering and assessment to decision-making and coercive action. It will do so by making better sense of huge amounts of data, detecting minute anomalies in adversarial behaviour, automating physical and cyber tasks, and providing super-human speed, precision, reliability, patience, and vigilance.Footnote 6 On the question of intelligence assessment, Boaz Ganor explains that rather than making the intelligence officer’s role redundant, AI makes their “work significantly more efficient”. He illustrates how AI will help human analysts make better sense of data, highlighting important (but obscure) relationships between singular points of information.Footnote 7 It will help turn disparate pieces of information into intelligence quickly, useful to decision-makers and soldiers on the frontline alike. For similar reasons, AI might likewise improve a state’s capacity in military planning, logistics, communications, recruitment, training, deployment, and so on. The back-office AI that better coordinates the machinery of warfare may make some especially complex coercive threats—like largescale international military operations—more robust, persuasive, and feasible. The automation of live-data analysis will provide states and militaries with an exploitable advantage over adversaries. Together, these factors may lead to “hyperwar”, in which data will be “sifted in near real time—if not eventually in real time”, providing decision-makers with greater awareness and more options far more quickly.Footnote 8

The factors encouraging hyperwar may lend themselves to the development of hyper-coercion: the ability to foresee and forestall an adversary’s next move. In the near term, by providing decision-makers with alternative tactical and strategic options based on a wide-ranging assessment of an unimaginably large trove of data and intelligence, AI may convince decision-makers to delegate some tasks (including targeting) to machines under specific time-sensitive conditions and constraints, ultimately forcing some states to re-evaluate current military assumptions, narratives, and plans regarding automation in warfare. In the long term, by providing unique advice to decision-makers that supersedes human innovation, AI may prove its value in providing situational awareness that dips into predictive analytics.Footnote 9 By melding an improved analysis of what adversaries have done in the past to what they are currently doing today (indeed, this very minute), AI may provide users with the ability to anticipate an adversary’s next move; defenders can pre-emptively respond accordingly and influence and deter adversarial behaviour to their liking.Footnote 10 Over time, once a challenger comes to believe that a defender can rely on sophisticated AI to properly anticipate its behaviour, it may be altogether dissuaded from pursuing certain actions. Something akin to AI-enhanced general deterrence might result.

Conversely, hyperwar and hyper-coercion may lead to deterrence failure and strategic instability instead. At least five dilemmas present themselves. First, on this theme, the RAND Corporation held several workshops in 2017 exploring future U.S. security challenges, circa 2040, illustrating the way AI might interfere with strategic (i.e. nuclear) deterrence.Footnote 11 They argue that if AI creates the perception among nuclear states that one country has the ability to detect, locate, and target all of another state’s nuclear weapon launchers—an infeasibility today but a possibility tomorrow given technological developments—then vulnerable states may be especially inclined to use these weapons more quickly at the risk of losing them altogether.Footnote 12 Other states may calculate that many more such weapons may be needed to offset an adversary’s ability to locate and target stockpiles, leading to an increase in both horizontal and vertical nuclear proliferation.

Second, as Keith Payne argues, AI will “change power balances” between rivals and should, all told, favour offence over defence, given the technology’s “speed, precision, and acquisition and analysis of unbiased … knowledge”.Footnote 13 These conditions may bolster deterrence by punishment strategies over deterrence by denial, in a repeat of Cold War dynamics.Footnote 14

Third, letting machines dictate the speed of warfare may inadvertently augment the effect of minor algorithmic glitches, inviting the development of accidental, and entirely AI-generated, deterrence failures.Footnote 15 Within an environment in which both challengers and defenders come to rely on AI to help guide behaviour, the systems themselves will interact with each other in unique (and uncertain) ways. Autonomous but unintended chain reactions may result; think of the market’s “flash crash” in 2010. The equivalent might be an unwanted “flash war” in either physical or digital space, an unintended conflict that results from the cascading effects of automated processes and responses between two opposing AIs. This is precisely the future scenario Matthew Price and colleagues contemplate, fictionalizing a two-hour long, AI-triggered war between the U.S. and China (circa 2024).Footnote 16 As the RAND study cautions, the conflagration ends in unintended and avoidable nuclear exchange. Price et al. use the narrative to explore how human decision-makers, who they suggest are “poor judges of risk under complexity”, might come to inherently rely on AI advice in order to ameliorate the “time pressures” endemic to periods of crisis. They note that deterrence, when put into practice, takes “the mind of the adversary”, and their “motivation” into consideration, such that failures of deterrence are failures “to understand an adversary”. By replacing human rationality with opaque computations of what human rationality looks look, AI risks obfuscating and undermining the traditional deterrence process.

Fourth, fighting at “machine speed” may change the calculus of taking action. If AI-based decision-making provides one side of a conflict an advantage in responding quickly and decisively, then others, where and when feasible, will eventually mimic and come to rely on these processes, too. But as both sides of a contest come to rely on machines for insights, the very rationale of these AI-generated insights may degrade more quickly over time, as one side’s AI responds and reacts to another’s, at a speed beyond human capacity (or control). Put another way, an AI-generated insight may have a short shelf life, and windows of opportunity may prove fleeting. If so, the logic and value of striking first, and fast, may prevail, upending long-standing coercive and escalatory calculations.

Finally, correctly gauging a country’s prowess in AI is open to misinterpretation, inviting coercive miscalculation along the way. A challenger, looking in, may be unable to properly gauge an adversary’s power when that power is itself derived from AI. Compared to traditional notions of power—like economic output, military leadership, or type and number of armaments—AI power is less measurable. If a challenger does not know what a defender is capable of, it may have less reason to restrain its behaviour. The conundrum, however, is that from a signalling perspective, even if a defender wanted to, it would be hard-pressed to accurately and clearly communicate its AI capability. How do you communicate a capability when that capability is a computer program?Footnote 17 Sharing the contents of an especially potent algorithm with an adversary to prove a point is a non-starter. If AI is to have a coercive effect, defenders will have to find creative ways to demonstrate or signal their capability, otherwise they invite adversarial miscalculation and, in certain cases, avoidable deterrence failures.

3 Commercial Dual-Use AI as Coercive Offset

AI is not a weapon; it is a technology with myriad and diverse uses. Michael Horowitz categorizes AI as the “ultimate enabler”, an all-purpose “technology with a multitude of applications”.Footnote 18 While it will certainly prove useful to states and militaries engaged in conflict and warfare, AI’s development is largely driven by other, often commercial, functions. And unlike other technological innovations that have weighed upon deterrence theory and practice over the century (i.e. nuclear weapons, submarines, ballistic missiles, missile defence), AI is a general-use technology largely driven by software developments and data collection. Competition for AI excellence will be broad as a result, uniquely combining the efforts of countries and corporations alike.Footnote 19 Horowitz argues further that the way AI develops in the coming years will help dictate the utility and advantage it might lend to its early military adopters. If AI advancements are led by the private sector, for instance, AI might more quickly “diffuse” to militaries around the world, who purchase it for their own use. That would reduce the original developer’s “first-mover advantage”, and could narrow the balance of power between innovators, purchasers, and adopters. But, conversely, if AI—or certain types of AI useful to defence—is developed primarily by states, government laboratories, and their militaries, the technology will be slower to spread between countries because of market restrictions, and innovators may retain a technological edge that translates into a longer-lasting coercive advantage. And yet, to date, there is no public evidence suggesting that any military in the world controls cutting-edge AI more sophisticated than that which is being developed or employed by leading technology firms, like Google or SenseTime.Footnote 20 Private tech appears to be leading the way.

These assertions are explored further by M. L. Cummings, who suggests that private sector innovation in AI currently has the advantage because top engineering talent find more lucrative careers in the commercial applications of AI than they do in the more narrowly-focused aerospace and defence industry. This is especially true in the U.S., Canada, and Europe. “The global defence industry”, she warns, “is falling behind its commercial counterparts in terms of technology innovation”.Footnote 21 Bridging the gap may be difficult. This sentiment is shared by Lieutenant General John Shanahan, Director of the U.S. Joint Artificial Intelligence Centre (JAIC), who explained in 2019 that unlike other forms of dual-use technology, “the barriers to entry” for AI are low. Shanahan explains:

Unlike most big weapon systems … that were dominated by the Defence Industrial Base, many if not almost all AI-enabled capabilities start in commercial industry. We are seeing a true democratization of technologies that, like so many other emerging technologies in history, are as capable of being used for bad as they are for good. It is going to be increasingly difficult to prevent the use of AI-enabled capabilities by those who are intent in causing harm.Footnote 22

The commercialization of AI presents traditionally weak states with a strategic (and coercive) opportunity. The dual-use nature of AI along with private-sector developments in the technology, suggests that smaller states and non-state actors, too, may eventually be able to purchase the technology for their own use. While weak actors may face other limitations, like acquiring access to appropriate training data, AI might nonetheless help level the playing field with more powerful actors. If so, diffusion of the technology may diminish how the strong deter or compel the weak, and might otherwise provide the weak with new avenues for coercing the strong. The weak can leverage the widespread availability of AI tools and techniques to develop new and imaginative ways to coerce, counter-coerce, or altogether defeat traditionally stronger military adversaries. Imagination and a willingness to experiment with AI at both the tactical and strategic level will prove useful here.

For illustration, Alina Polyakova’s introduces “AI-driven asymmetric warfare”. With Russia in mind, she shows how weaker adversaries might “co-opt existing commercially available” AI technology to challenge stronger states with AI-enhanced cyberattacks and AI-generated disinformation campaigns. She suggests that “deep fake” technology—which allows a user to swap one person’s face for another in synthetic video contentFootnote 23—can produce highly realistic and customized content useful for strategically shifting narratives and perceptions in target societies and (when done right) changing individual and government behaviour. By manipulating public information through deep fakes and other related processes, AI might provide users with new forms of deterrence by delegitimization.Footnote 24 The threat, in this case, is the ability to create, release, and disseminate fake video or audio material threatening or embarrassing to a target. Think of Russia surreptitiously threatening a U.S. congressional or presidential nominee with engineered content that could influence the candidate’s standing among the electorate. Because determining the veracity of AI-manipulated content and attributing its source is difficult to do, countering these types of coercive misinformation campaigns may prove difficult.Footnote 25 Or consider other as-of-yet developed but no less unique applications for AI in physical space. Autonomous CBRN weapons—aerial or underwater “doomsday” drones—could be deployed by a weaker state to dissuade a stronger challenger from launching a debilitating first strike, augmenting the credibility of new-age second strike weapons.Footnote 26 Fanciful, perhaps, but worth imagining in both theory and practice when contemplating the future of deterrence.

4 Autonomous Weapons and the Advent of Saturation Tactics

If AI is narrowly defined as “machine learning”, then it might be argued that some militaries have been using AI techniques and statistical learning models for years in order to improve weapons and signal processing systems. The difference today, however, is the dramatic improvement in the quantity of data and quality of processing power available for use. Countries or militaries that can combine these two elements will broaden the boundaries of what they can currently accomplish with AI technology, likely acquiring a noticeable (and potentially significant) edge over adversaries and allies alike.Footnote 27 Of all the debates surrounding AI and warfare, greatest popular and media concern is reserved for Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (LAWS). For the latest popular iteration of this movement, simply Google “Slaughterbots”. By broadest definition, critics present LAWS as any weapon platform that has the ability to select, target, and engage an adversary autonomously.Footnote 28 While important ethical, practical, and legal concerns have been levied against fully autonomous offensive weapons,Footnote 29 the purpose of this chapter is centred on exploring the coercive effect, rather than the moral consequence, of AI, including those married to robotic systems.

For clarity, weapon systems can be provided different levels of autonomy. As Scharre describes in Army of None, if a human remains “in the [Observe, Orient, Decide, Act (OODA)] loop deciding which target(s) to engage”, the system in question should be considered a semiautonomous weapon. In this case, the search and detection of a target may be autonomous, but a human decides to engage and destroy a target. Contemporary drone warfare follows this pattern of behaviour. Conversely, with autonomous weapon systems, the entire process of identifying, detecting, and engaging a target is done autonomously. That is the battlefield of the near future. Yet even here, autonomous weapons can be further sub-subdivided. On one hand, supervised autonomous weapons, like those widely used to defend naval ships, bases, and other potential targets from missile or rocket attack, engage autonomously with a target (usually an incoming projectile), though humans remain in the loop and supervise the weapon’s use. A human can intervene if and where needed. Fully autonomous systems, on the other hand, perform the entire decision process autonomous and human intervention is not possible. Using the loop analogy, Daniel Hoadley and Nathan Lucas (and others) suggest that humans can be in the loop (semi-autonomous), on the loop (human supervised autonomous systems), and out of the loop (fully autonomous systems).Footnote 30

While Scharre argues that very few contemporary weapon systems have crossed into the fully autonomous category, some have, and more are expected to.Footnote 31 Contemporary examples include the Israeli Aerospace Industries’ Harpy—a drone-like weapon that can loiter above a prescribed location for hours until it engages with a specific target. As Scharre explains, while a human decides to launch the Harpy in order to “destroy any enemy radars” within a proscribed geographic area and timeframe, the Harpy itself “chooses the specific radar it destroys”.Footnote 32 In this case, the human does not know in advance, even when launching the weapon, which specific target the weapons will choose to destroy; the weapon determines who to kill. There is a distinction, then, between a machine ordered by a human to target something or kill someone, and a machine deciding on its own to target something or kill someone. At issue, for both opponents and proponents of these systems, is that fully autonomous and offensive weapons systems are being developed and are likely to be more widely used in future conflicts and wars.

In this case, autonomous weapons will lead to the potentially rapid development of new military tactics, shifting the traditional divide between offense and defence and punishment and denial, altering coercive calculations along the way. In this vein, saturation tactics have been given the most attention, in which thousands of miniature, cheaply made, and disposable autonomous systems are used to swarm and overwhelm a target.Footnote 33 The tactic usually references unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV; i.e. drones), but could just as well eventually involve unmanned ground vehicles (UGV; i.e. self-driving or—walking machines) and unmanned underwater vehicles (UUV; i.e. underwater drones). On its own, a single unmanned and autonomous unit is no match for a fighter jet or destroyer, but algorithmically lassoed together, a fleet of thousands might well overwhelm these larger and more cumbersome platforms. The tactic lends itself to both offensive and defensive processes. Horowitz suggests that low-cost, autonomous drones, coordinating their actions at machine speed, might undermine high-cost, high-quality legacy weapon systems.Footnote 34 Michael O’Hanlon adds further that these tactics might end “the kind of impunity that U.S. forces have enjoyed for decades”.Footnote 35 Here again, innovation in imagination—rather than simply access to these sorts of autonomous platforms—may provide a nimble adversary with a coercive advantage.

5 Leveraging Moral Asymmetries for Coercive Gain

Ethical, political, and legal limitations on how AI is used in warfare may dictate how some countries behave and others respond. Some countries, notably the United States and several European allies, are (currently) openly against providing AI with the right or the means to kill individuals without human intervention—while promoting his country’s AI innovation strategy, French President Emanuel Macron retorted that he was “dead against” the idea.Footnote 36 But other states, including U.S. adversaries, warn Darrell West and John Allen, are “not nearly so mired in this debate”, or hamstrung by these concerns.Footnote 37 China, Russia, Israel, and others may be more willing to delegate decisions to AI. The emerging moral asymmetry introduces several interesting quandaries for thinking through the future of deterrence.

First, allies with asymmetric AI capabilities, uneven AI governance structures, or different AI rules of engagement, may find it difficult to work together towards a common coercive goal. Interoperability is central to collective defence and alliance coercion.Footnote 38 States with uneven development in AI may find it problematic to collaborate in theatre; the AI have-nots (and AI choose-nots) may function at a lower speed of operation, dragging the coalition’s ability and credibility down with it. An inability to find common ground on when or how (or even whether) to use AI in strategic affairs may lead to a similar dilemma. Allies who differ on AI ethics might be unwilling to share useful training data or to make use of shared intelligence derived from AI. Without broader consensus, then, AI may weaken political cohesion within alliances, making them less effective as a result.

Second, lowering the bar on ethics and AI may become a strategic advantage: some challengers may derive a coercive advantage by signalling or communicating a willingness to develop, use, and rely on AI in warfare in ways that defenders have openly agreed against.Footnote 39 A belligerent, for illustration, might communicate a readiness to provide its AI with greater control over target engagement, or to field certain autonomous weapons systems, in order to compel or influence an adversary’s behaviour. Some states might respond by purposefully shrouding their ethical standards when it comes to their own use of AI if only to safeguard against other’s taking advantage of a known moral position, a twist on Thomas Schelling’s “threat that leaves something to chance” (mis)appropriated to the AI era.

Third, and closer to home, ethical standards and considerations might likewise influence the very development of AI and the nature of alliance politics. This may be especially true in liberal democracies. To some, private sector considerations are a strategic consideration; the AI “commercial ecosystem” is small (less than ten thousand people, globally, determine the next generation of AI).Footnote 40 To a certain degree, then, the political and ethical preferences of the commercial American, Canadian, and European AI community will help determine how AI will be used within a military context among trans-Atlantic allies. The question “these folks ought to ask themselves is: What if we just don’t utilize our expertise and cede this field to other countries; what if we just walk?”Footnote 41 The ramifications could include a strategic imbalance that favours NATO adversaries—notably China—who are purposefully building public-private collaborative AI hubs to ensure the full diffusion of the technology from the private sector to the public sector.

For the U.S., Europe, and Canada, deriving military or security benefit from AI developments taking place in the private sector will require generating incentives for public-private collaboration that meets the evolving standards of firms and/or attracts experts who might otherwise find employment at tech companies. Other states face fewer such constraints. Chinese corporations, for instance, appear far more eager, or are outright compelled, to work with the government; AI innovations are all but certain to trickle into military, intelligence, and security application. Thus, while Canada, parts of Europe, and the U.S. are ahead of China in terms of generating AI research, “China is crushing in the actual application of AI”.Footnote 42 Other countries provide alternative lessons: Israel’s model uniquely links industry, academia, and the state together, all working towards a complementary goal in support of each other.Footnote 43 Ultimately, embedding national AI strategies with the right balance of ethics and use may well lend itself to future deterrence calculations.

6 Enhancing the Credibility of Military Action

AI introduces a range of opportunities to combat environments, making some coercive threats more credible as a result.Footnote 44 By providing military systems with greater autonomy, for example, AI replaces humans in dangerous, complex, and labour-intensive jobs; the notion of a suicide mission may cease to influence decision-makers.Footnote 45 AI might likewise make “long-duration tasks that exceed human endurance” more feasible to plan and pursue.Footnote 46 Making sense of a huge quantity of data from disparate sources, AI might also provide military planners with suggested solutions that allow them to outpace an adversary’s own assessment of and ability to strategically react to a situation if left to human analysis alone. Further, AI might provide out-of-the-box and unpredictable tactical advice that stretches the human imagination and experience. AI might likewise boost the productivity and capability of intelligence and military personnel, frontline soldiers, and of entire military institutions.

All told, AI might sufficiently alter the way conflict and war unfold, influence how states and militaries rely on and utilize both deterrence by denial and deterrence by punishment. On the former, by improving the speed and accuracy of some defensive weapons, and by subsequently improving the reliability of defending infrastructure and territory against certain kinetic attacks, AI might deter some types of behaviour by altogether denying their utility. The same holds when pairing AI to cyber deterrence: by denying aggressors access to information or networks more persistently, a defender’s AI might compel a challenger not to bother attacking in the first place. In this vein of thinking, AI augments a defender’s capability to defend, stripping away a challenger’s ability to acquire what it hopes to accomplish. By denying success, AI deters behaviour. On the latter, however, and under other conditions, AI may augment the feasibility of certain types of offensive attack, altogether favouring punishment over denial. Autonomous swarming robotic platforms, as noted, have garnered the greatest attention: when refined, swarming bots may provide challengers with a unique coercive tool not easily deflected or defeated. Saturation tactics that rely on thousands of disposable robotic platforms working together may tip the balance towards offensive measures and the promise of punishment strategies.

Importantly, Zachary Davis makes a distinction between AI’s application at the tactical and operational level of warfare—“the way wars are fought”—and the strategic level—actions that relate to the balance of power and “major conflicts between great powers”, suggesting that adoption of AI in the former may lead to changes in deterrence in the latter. Davis explains that AI is already being used in military logistics, planning, and transportation, intelligence analytics and object identification, and in war gaming and training. Put together, these advancements might alter strategic calculations. He argues that AI might provide a state with the appearance of having the ability to conduct both a “disarming counterforce strike” against an adversary’s retaliatory forces, and to shoot down remaining retaliatory capabilities with augmented defensive systems.Footnote 47 What counts, here, is perception: an adversary’s belief in another’s superior capabilities, which invites instability in the form of misperception, miscommunication, and miscalculation.Footnote 48 As Keith Payne reminds us in Strategy, Evolution, and War (2018), “strategy…is an intensely psychological activity”.Footnote 49 It requires an actor to properly judge an adversary’s motivation, beliefs, and thought. Deterrence, then, is applying pressure on an adversary such that you alter his intention. Payne, taking a biological, cognitive, sociological, and historical perspective on strategy, suggests that social life entails an ability to gauge, anticipate, and respond to an adversary’s behaviour. He finds, ultimately, that AI may influence these processes, undermining the traditional expectation that defensive measures outweigh offensive ones in deterrence.

7 Conclusions: Next Steps for AI and Deterrence

Deterrence has been around a long time; it has repeatedly proven its theoretical flexibility in responding to shifting international dynamics and emerging technologies. As this volume suggests, this evolution has occurred within the context of distinct “waves” of scholarship, with a fifth now emerging. While AI will certainly shape this emerging wave in novel and unique ways, the actual study of AI and deterrence and coercion has only just begun. The emerging scholarship is necessarily speculative: not only is AI still an imperfect technology, but its application to warfare, intelligence, and national security is uneven and uncertain. Significant ethical, legal, and political considerations have yet to be hashed out. And a robust research program on AI deterrence has yet to be concretely conceived. What follows are suggestions for next steps in further developing and empirically testing AI deterrence theory.

From a theoretical perspective, a broadening of the conceptual field of research is needed. IR scholarship does not own deterrence. Scholars of psychology, criminality, terrorism studies, and computer science have made recent advancements in developing deterrence theory for countering crime, terrorism, and cybersecurity by applying insights from their distinct disciplines. These insights have proven useful to scholars of IR and military deterrence despite their interdisciplinary origins. Something similar should take place with the study of AI deterrence, which has all the hallmarks of requiring a cross-disciplinary lens. While this chapter—and much of the literature cited within it—explores how traditional IR intersects with AI deterrence, lessons from other fields where AI is making inroads and shaping individual and group behaviour, would provide a more fulsome theoretical picture.

For illustration, ubiquitous AI real-time surveillance is deterring criminal behaviour; China’s experiment in deterring jaywalkers is informative.Footnote 50 Facial recognition cameras snap pictures of pedestrians breaking the law, matching the offender to photo IDs stored in a database. The individual’s personal information can then be displayed online and on roadside screens—deterrence by embarrassment?—and fines can be issued automatically. In the city of Ji’Nan, the technology reduced jaywalking by 90%. What lesson might this criminological application of AI hold for IR deterrence and defence? If a state where to establish AI-powered surveillance of urban centres, border crossings, and other sensitive locations to generate biometric identification and behavioural analytics—notwithstanding concerns over personal privacy—and if it were to publicly announce its use of these tools, it might convince others besides jaywalkers, like organized criminals, terrorists, insider threats, and foreign spies, that their plans are unlikely to succeed, deterring other forms of unwanted behaviour.Footnote 51 Similar insights relevant to IR might be culled from cybersecurity’s application of AI to behavioural dynamics in cyberspace. A multi-pronged approach will prove useful for developing robust theories of AI deterrence across the disciplines.

From an empirical perspective, qualitative case studies—and where applicable, quantitative analysis—should be conducted, testing the integrity and strength of the emerging theoretical propositions. Very little empirical work on AI and deterrence has taken place to date. Professor Wilner’s research in this area, as part of his multi-year AI Deterrence project, does provide some early and preliminary empirical lessons however, suggesting avenues for further exploration. One of the project’s case studies explores the coercive effects AI might have on European border security.Footnote 52 Several scientific explorations are ongoing in Europe, testing the use and utility of applying AI to border and national security considerations. For illustration, the EU’s iBorderCtrl program, field tested in 2019, uses AI avatars at select border crossings in Greece, Hungary, and Latvia to facilitate more thorough border control. In essence, travellers interact with the AI avatar, which is a computer-generated human-like figure displayed on a computer screen. The avatar asks the traveller questions, analysing responses by scanning the individual’s facial characteristics for “micro-expressions” of stress, useful for detecting deception. Micro-expressions are indistinguishable to humans, so machines make a first assessment of an individual’s overall risk. iBorderCtrl suggests the project is meant to “speed up the border crossing at the EU external borders and at the same time enhance the security and confidence regarding border control checks”.

Wilner’s AI Deterrence research team uses the border case study to explore the ramifications of experiments like iBorderCtrl on the future of physical coercion. Early results from the empirical work help situate deterrence continuity and change in an age of AI, with insights useful across the disciplines, including in IR. First, AI deterrence is a function of a process, not the immediate result of the technology itself. Second, AI deterrence is ultimately about finding the right balance between communicating, signalling, or illustrating capabilities and safeguarding those technological advantages. Third, AI deterrence may lead to deflection, displacement, and adversarial adaptation, undermining presumed deterrence successes. Fourth, and relatedly, actually measuring AI deterrence success requires fabricating a complicated counterfactual, definitively linking the technology itself to behaviour that ultimately did not take place. And fifth, ethics will play an oversized role in AI deterrence, driving the process of justification and applicability and informing the technology’s use and utility. As AI becomes more fully integrated into society, policing, cybersecurity, intelligence, national security, and defence, other empirical lessons from a diverse set of circumstances will lend themselves to the scholarly evaluation and improvement of AI deterrence theory.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

Some authors are less sanguine about the utility AI will have in national security, suggesting the current technology is easily duped, spoofed, or exploited, does not easily lend itself to very simple cross-domain tasks, and cannot often explain how outputs were produced. Other scholars note that technological innovation does not necessarily lead to conflict escalation and novel deterrence outcomes. Horowitz 2018c; Altmann and Sauer 2017, pp. 119–120; Talmadge 2019, pp. 867–869.

- 4.

- 5.

The project received two grants from Canada’s Department of National Defence’s Innovation for Defence Excellence and Security (IDEaS) program (2018/19, and 2020/2021), and a third from DND’s Mobilizing Insights in Defence and Security (MINDS) program (2019/2020).

- 6.

Horowitz et al. 2018.

- 7.

Ganor 2019.

- 8.

West and Allen 2018.

- 9.

Morstatter et al. 2019.

- 10.

- 11.

Geist and Lohn 2018.

- 12.

For a similar argument centred on the effects of “non-kinetic left-of-launch capabilities” (i.e. cyber and missile defence) on the stability of current nuclear deterrence structures, see Wasson and Bluesteen 2018.

- 13.

Payne 2018a.

- 14.

Wilner and Wenger 2021.

- 15.

- 16.

Price et al. 2018, pp. 92–105.

- 17.

With thanks to the participants of the AI Deterrence Stakeholder Meeting, May 2019, Ottawa, Canada.

- 18.

Horowitz 2018a.

- 19.

Horowitz 2018b.

- 20.

Author Interview, Brookings Institution, Washington DC, January 2019.

- 21.

Cummings et al. 2018.

- 22.

Rassler 2019.

- 23.

Wilner et al. 2019.

- 24.

For an exploration of deterrence by delegitimization, see Long and Wilner 2014.

- 25.

Knight 2018.

- 26.

Geist and Lohn 2018.

- 27.

Author Interview, Brookings Institution, Washington DC, January 2019.

- 28.

International Committee of the Red Cross n.d.

- 29.

- 30.

Hoadley and Lucas 2018, pp. 24–26.

- 31.

PAX for Peace 2019.

- 32.

Scharre 2018b, ch. 3; Author Interview, CNAS, Washington DC, January 2019.

- 33.

- 34.

Horowitz 2018a.

- 35.

O’Hanlon 2018.

- 36.

Thompson 2018.

- 37.

West and Allen 2018.

- 38.

With thanks to the participants of the AI Deterrence Stakeholder Meeting, May 2019, Ottawa, Canada.

- 39.

Author Interview, CNAS, Washington DC, January 2019.

- 40.

Author Interview, Brookings Institution, Washington DC, January 2019.

- 41.

Ibid.

- 42.

Author Interview, CNAS, Washington DC, January 2019.

- 43.

Author Interview, Brookings Institution, Washington DC, January 2019.

- 44.

Hoadley and Lucas 2018.

- 45.

Conversely, Erik Gartzke argues that “automatic combat reduces the costs faced by the technological power”, thus reducing its ability to demonstrate resolve: it appears to have less (of value) to lose: Gartzke 2019.

- 46.

Ibid.

- 47.

Davis 2019, pp. 118–121.

- 48.

For Davis, AI poses a challenge to current thinking on coercion because of its effect on surprise attacks and on “mutual strategic vulnerability”. Ibid.

- 49.

Payne 2018b.

- 50.

Han 2018.

- 51.

Mosur 2019.

- 52.

A series of expert interviews were held at the Border Security AI Research Observatory, Frontex; GCHQ; Royal United Services Institute; European Union Institute for Security Studies; Université Libre de Bruxelles; Alan Turing Institute; Darktrace; and Stiftung Neue Verantwortung (SNV), Germany. Interviews took place between January and March 2020. Data were anonymized, in accordance with the project’s research ethics protocol (Carleton University, 2021).

References

Altmann J, Sauer F (2017) Autonomous Weapons Systems and Strategic Stability. Survival 59.5:119–120

Brookings (n.d.) A Blueprint for the Future of AI. https://www.brookings.edu/series/a-blueprint-for-the-future-of-ai/

Coker C (2015) Future War. Polity

Conn A (2018) The Risks Posed by Lethal Autonomous Weapons. Future of Life Institute (September 2018)

Cummings M L et al (2018) Artificial Intelligence and International Affairs. Chatham House Report 7–18

Davis Z (2019) Artificial Intelligence in the Battlefield. PRISM 8.2:118–121

European Parliament (2017) Towards an EU Common Position on the Use of Armed Drones

Ganor B (2019) Artificial or Human. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism

Gartzke E (2019) Blood and Robots: How Remotely Piloted Vehicles and Related Technologies affect the Politics of Violence. Journal of Strategic Studies 15

Geist E, Lohn A (2018) How Might Artificial Intelligence Affect the Risk of Nuclear War? RAND

Han M (2018) AI Photographs Chinese Jaywalkers; Shames them on Public Screens. Medium, 9 April 2018

Hoadley D, Lucas N (2018) Artificial Intelligence and National Security. Congressional Research Service, pp 24–26 (April 2018)

Horowitz M (2018a) Artificial Intelligence, International Competition, and the Balance of Power. Texas National Security Review (May 2018)

Horowitz M (2018b) The Algorithms of August. Foreign Policy (September 2018)

Horowitz M (2018c) The Promise and Peril of Military Applications of Artificial Intelligence. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

Horowitz M (2019) When Speed Kills: Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems, Deterrence, and Stability. Journal of Strategic Studies 42:6

Horowitz M et al (2018) Artificial Intelligence and International Security. CNAS

Huh Wong Y et al (2020) Deterrence in the Age of Thinking Machines. RAND

International Committee of the Red Cross (n.d.) Autonomous Weapons: Decisions to kill and destroy are a human responsibility. https://www.icrc.org/en/document/statement-icrc-lethal-autonomous-weapons-systems

iPRAW (2017) Focus on Computational Methods in the Context of LAWS

Knight W (2018) The Defense Department Has Produced the First Tools for Catching Deep Fakes. MIT Technology Review

Lappin Y (2017) Artificial Intelligence Shapes the IDF in Ways Never Imagined. The Algemeiner (October 2017)

Long J M, Wilner A (2014) Delegitimizing al-Qaida. International Security 39:1

Morstatter F et al (2019) SAGE: A Hybrid Geopolitical Event Forecasting System, Proceedings of the Twenty- Eighth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (August 2019)

Mosur P (2019) One Month, 500,000 Face Scans. New York Times, 14 December 2019

O’Hanlon M (2018) The Role of AI in Future Warfare. Brookings

PAX for Peace (2019) Slippery Slope: The Arms Industry and Increasingly Autonomous Weapons (November 2019)

Payne K (2018a) Artificial Intelligence: A Revolution in Strategic Affairs? Survival 5

Payne K (2018b) Strategy, Evolution, and War. Georgetown UP

Price M, Walker S, Wiley W (2018) The Machine Beneath. PRISM 7.4:92–105

Rassler D (2019) A View from the CT Foxhole. CTC Sentinel 12.11

Scharre P (2014) Robotics on the Battlefield, Part II. CNAS

Scharre P (2018a) A Million Mistakes a Second. Foreign Policy (September 2018)

Scharre P (2018b) Army of None. W.W. Norton

Solls B (2020) Now Hiring AI Futurists. ZDNet, 20 May 2020

Talmadge C (2019) Emerging Technology and Intra-war Escalation Risks. Journal of Strategic Studies 42:6

Thompson N (2018) Emmanuel Macron Talks to Wired about France’s AI Strategy. Wired (March 2018)

Wasson J, Bluesteen C (2018) Taking the Archers for Granted: Emerging Threats to Nuclear Weapon Delivery Systems. Defense Studies 18:4

Wenger A, Wilner A (2012) Deterring Terrorism. Stanford University Press

West D, Allen J (2018) How Artificial Intelligence is Transforming the World. Brookings Institution (April 2018)

Wilner A (2015) Deterring Rational Fanatics. University of Pennsylvania Press

Wilner A (2019) Artificial Intelligence and Deterrence: Science, Theory, and Practice. NATO Science and Technology Organization (STO), MP-SAS-141-14

Wilner A (2020) US Cyber Deterrence: Practice guiding Theory. Journal of Strategic Studies 43.2

Wilner A et al (2019) The Threat of Digital Foreign Interference: Past, Present, and Future. Macdonald Laurier Institute

Wilner A, Wenger A (2021) Deterrence by Denial: Theory and Practice. Forthcoming, Cambria

Wittes B, Blum G (2015) The Future of Violence. Basic Books

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wilner, A., Babb, C. (2021). New Technologies and Deterrence: Artificial Intelligence and Adversarial Behaviour. In: Osinga, F., Sweijs, T. (eds) NL ARMS Netherlands Annual Review of Military Studies 2020. NL ARMS. T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6265-419-8_21

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6265-419-8_21

Published:

Publisher Name: T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague

Print ISBN: 978-94-6265-418-1

Online ISBN: 978-94-6265-419-8

eBook Packages: Law and CriminologyLaw and Criminology (R0)