Abstract

Tropical forests significantly contribute to local livelihoods as well as global carbon storage and biodiversity conservation. Therefore, a strategy that harmonizes a better quality of life for local people with tropical forest conservation is required. In Community-based ecotourism (CBET), the local community participates in related economic activities. In this chapter, we summarize our current studies that quantified the contribution of CBET to the income and livelihoods of local people and forest conservation. We selected the Chambok CBET site in Cambodia for our case study. First, we quantified the effectiveness of CBET in forest conservation by analyzing forest cover change with published maps created from satellite images. Second, we evaluated the contribution of CBET to household income and livelihood changes through a household survey using a questionnaire. Analysis of the forest cover change maps revealed that deforestation had significantly decreased inside the CBET area as compared to outside it, although the reduction was not enough to stop net deforestation. The survey revealed that the total monthly income of CBET member households and non-CBET households was not significantly different. It also showed that the community members felt the livelihood change after the implementation of CBET. However, this change may have been caused by general socioeconomic changes in Cambodia. We conclude that CBET effectively contributed to forest conservation but in a limited capacity to household income.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Tropical forests play a major role in global carbon storage (Bonan 2008; Sullivan et al. 2017) and are also global centers of biodiversity (Scheffers et al. 2012). However, deforestation and forest degradation in tropical areas have become a global concern over the past few decades (Achard et al. 2002; Hansen et al. 2013). While forest cover has increased in some tropical countries in the last decade (FAO 2015; IPBES 2018), severe deforestation and forest degradation is still happening in the tropical forests of many countries. Southeast Asia witnessed a reduction of 12.9% in forest cover between 1990 and 2015, largely caused by an increasing export market for palm oil, pulp, rubber, and timber products (IPBES 2018). Deforestation and forest degradation have put tremendous pressure on biodiversity (Newbold et al. 2014) and forced tropical forests to become a net carbon source (Baccini et al. 2017). Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop mitigation strategies.

In addition to their contribution to the global storage of carbon and biodiversity, tropical forests have also been recognized as an important resource of local livelihoods (Sunderlin et al. 2005). For example, in Cambodia, which is our study site, more than 90% of rural households depend on fuelwood as a primary source for cooking and other activities (Top et al. 2004; San et al. 2012). Thus, any conservation strategy that excludes local people from forests may inevitably affect local livelihoods. Therefore, we need a strategy that harmonizes forest conservation with the quality of life for local people in tropical areas.

Community-based ecotourism (CBET), a kind of community-based forest management, is one of the strategies that could improve both quality of life for local people and conservation efforts in tropical forests. In particular, CBET is where the local community participates in related economic activities (Kiss 2004). Because CBET can generate economic benefits, it is seen as a tool for affording a better quality of life for the participating community. In addition to the economic benefits, CBET may contribute to the conservation of natural resources in a CBET area—natural resources that tourists find attractive are conserved for ecotourism. Thus, CBET may motivate the local community to conserve the area’s forests. Reflecting expectations for its benefits, CBET has become popular worldwide. While a number of studies evaluate its impact (see Das and Chatterjee 2015), most of these are qualitative (Das and Chatterjee 2015); there have been fewer efforts to accumulate quantitative data to evaluate the effectiveness of CBET, which include our recent attempts (Lonn et al. 2018b, 2019). While the need for evidence-based decision-making is paramount, it is possible only by collecting quantitative data on local people’s livelihoods and forest conservation.

We, therefore, evaluate the effectiveness of CBET by presenting quantitative data on forest cover change in a CBET area and the total income of CBET members. In this chapter, we demonstrate the effectiveness of CBET by summarizing findings from our recent studies (Lonn et al. 2018b, 2019). We first briefly characterize our study site and, then, evaluate how the forest has been conserved through CBET. Finally, we discuss how CBET contributes to household income and livelihood changes.

2 Chambok CBET

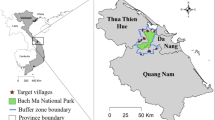

The Chambok CBET site, a flagship model of CBET in Cambodia, was selected as the study area because it is regarded as a good practice of CBET in Cambodia (e.g., Prachvuthy 2006). It is located in the Chambok Commune, Phnom Sruoch District, Kampong Speu Province, southwestern Cambodia (Fig. 9.1). This Commune officially consists of four villages. Its total number of households and population in 2008 were 761 and 3670, respectively (NIS 2008). Half of the Commune has been designated as a national park, called the Kirirom National Park (KNP). According to a 2010 forest cover map of the Forestry Administration in Cambodia, 44% of the total Commune land comprises deciduous forests, followed by 25%, 16%, and 7% of non-forest areas, evergreen forests, and semi-evergreen forests, respectively.

Maps of the Chambok Commune and Community-based ecotourism (CBET) conservation area. We used the World Borders Dataset provided by Thematic Mapping (http://thematicmapping.org/) to show the country’s border. The boundaries of Chambok CBET conservation zones were provided by the Mlup Baitong Organization. Forest cover change maps created by Hansen et al. (2013) were used to calculate forest cover in 2000

Traditionally, the community was heavily dependent on forest resources and caused deforestation and forest degradation due to overexploitation (Prachvuthy 2006). Therefore, Mlup Baitong, a local environmental non-governmental organization, embarked on a project in 2002, aiming to improve the quality of life for the local people and forest conservation. The Chambok CBET program was opened for visitors the following year. Until 2010, Mlup Baitong supported the program; since 2011, the local people have been managing it themselves.

The main attractions of the CBET area are the surrounding forests, a 40-meter waterfall, and local streams (Fig. 9.2). In addition to spending time in the forests and by the water bodies, tourists can enjoy cycling, meals at restaurants, and cultural events such as traditional children’s dancing, cooking traditional food, and homestays. According to the Chambok CBET committee, approximately 10,000 tourists visited the site in 2010. The revenue from the program was utilized not only for paying wages but also for infrastructure development, forest conservation in the CBET area, and assistance for poor households among other things. There is no strict rule for undertaking CBET activities, and any Cambodian citizen living in the Commune can work for CBET-related businesses.

It should be noted that not all Commune areas are assigned to the forest conservation zone of the Chambok CBET (Fig. 9.1). This zone comprises three community-protected areas (CPAs) and three community forestry areas (CFAs). The total area of the conservation zone is 10.42 km2, which is approximately 13% of the total Commune area. The differences between CPAs and CFAs are the locations and the managing authorities. CPAs are located inside the KNP under the management of the Ministry of Environment of Cambodia, while CFAs are located outside the KNP under the management of the Forestry Administration. However, we have not considered these differences in this chapter because they cooperatively implement the CBET program.

3 Contribution to Forest Conservation

Among the many ways to evaluate the effectiveness of CBET on forest conservation, satellite data can provide wall-to-wall information on forest cover change. Here, we summarize the result obtained from satellite data analysis (Lonn et al. 2019), with which the effectiveness of CBET was evaluated by comparing the forest cover change inside and outside the CBET area. Further details of this comparison have been reported by Lonn et al. (2019)

We used forest cover change maps created from the Landsat satellite (Hansen et al. 2013); a detailed description of the maps is available on his website (https://earthenginepartners.appspot.com/science-2013-global-forest/download_v1.1.html). To explain briefly, the data, provided as approximately 30-m spatial resolution raster files, includes the tree canopy cover in 2000 and forest loss or gain between 2000 and 2012 per pixel. From this data set, we calculated deforestation and forest recovery between 2000 and 2012 in the Chambok Commune. We defined forest, deforestation, and forest recovery as follows: we defined the forest cover in 2000 using the tree canopy cover of that year; the threshold of tree canopy cover was set to 30%. Then, we considered that “deforestation” occurred on the pixels that were “forests” in 2000 but were classified as “no forest” by 2012, and “forest recovery” occurred on the pixels that were “no forest” in 2000 but were classified as “forest gain” by 2012.

Using the published forest cover change maps, we conducted a two-fold analysis—a direct comparison and taking a quasi-experimental approach. For the comparison, we calculated the deforested and forest recovery portions both inside and outside the CBET area and compared the values. We did this to determine net forest cover change inside and outside the CBET area.

In addition to this, we used a quasi-experimental approach to evaluate the effectiveness of CBET. This was done because the location of CBET had not been chosen randomly, and it was deduced that the simple comparison could yield biased results. For example, forests that are close to villages or main roads may be chosen as CBET areas due to the higher accessibility for local people and tourists. On the other hand, previous studies have demonstrated that the distance to villages or main roads affects the likelihood of forest loss (Lonn et al. 2018a), because accessibility to a forest increases with its proximity to a village or main road. In other words, the distance to a village or main road may covary with both forest loss and the distribution of CBET. For comparison between inside and outside the CBET area, we need to control this confounding for minimizing the bias due to the correlation between covariates. A quasi-experimental approach can minimize the bias by balancing the distribution of covariates (Stuart 2010). For our analysis, we used a matching method as the quasi-experimental approach. This method compared forest cover change inside the CBET area with the change outside the CBET areas that are very similar to those inside the CBET area for distance to a village or a main road. We employed the matching method using eight covariates, including distance to the nearest road and nearest river. The analysis was conducted with R ver. 3.3.3 (R Core Team 2019) using the “Matching” package (Sekhon 2015).

Deforestation and forest recovery in the Chambok Commune are shown in Fig. 9.3; deforested areas are mainly distributed in the eastern part of the Commune (Fig. 9.3). In addition, it seems forest loss occurred more frequently outside the CBET area, while there were a few cases of the same inside. When we compare deforested areas inside and outside the CBET area, both show net decreases in forest cover (Lonn et al. 2019). This result means that the effects of CBET were not enough to stop net deforestation.

While the simple comparison reveals that CBET cannot stop net deforestation, the matching method result shows that deforestation reduced by 2% (p < 0.01) inside the CBET area compared to outside it (Lonn et al. 2019). Similarly, it also shows that forest recovery was promoted by 0.5% inside the CBET area as compared to outside it, although the difference was not statistically significant at the 0.1 level (Lonn et al. 2019).

4 Contribution of CBET to Household Income

Here, we summarize the result from the household survey to quantify the contribution of CBET to household income, from Lonn et al. (2018b). A survey questionnaire to interview both CBET member households and non-CBET households, selected systematically, was conducted. In particular, we visited every second household along the main roads and sub-roads in four villages. This was done keeping in mind that the household locations may affect the income of the local people or their livelihoods (Ameha et al. 2014; Rasolofoson et al. 2017). In all, 174 households—77 CBET and 96 non-CBET—were selected from the survey. These accounted for 23% of the total households in the Commune. Details about the questionnaire are described in Lonn et al. (2018b). To explain briefly, our questionnaire included questions on current income and its source, socioeconomic status, and perceptions of livelihood before and after the introduction of the CBET project.

Figure 9.4 represents the total monthly income and ecotourism income of CBET and non-CBET households. Here, ecotourism income includes any ecotourism-related work (e.g., accommodation charge for homestays and wages for working at the CBET site). The median and mean of the ecotourism income of CBET households were 1.2 and 10.1 USD, respectively.

Monthly income and expenditure distributions of CBET and non-CBET households from Lonn et al. (2018b)

Distributions of the total income, which included income from other sources in addition to ecotourism, were very similar between CBET and non-CBET households (Fig. 9.4). The median and mean of the total income were US $74.1 and 103.7 for CBET households, and US $64.3 and 81.5 for non-CBET ones, respectively (Lonn et al. 2018b). The interview on the perception of livelihood change showed that 60.5% and 42.7% of CBET and non-CBET households, respectively, felt an increase in the quality of their livelihood (Lonn et al. 2018b). On the other hand, 18.4% and 40.0% of CBET and non-CBET households, respectively, felt a decrease in the quality of their livelihood (Lonn et al. 2018b). Both CBET and non-CBET households had similar perceptions of why their livelihood had changed, which is improvement in employment (Lonn et al. 2018b). Only 2% and 0% of CBET and non-CBET households, respectively, felt ecotourism had improved their livelihood (Lonn et al. 2018b).

5 Discussion and Conclusion

In this chapter, we quantified the contribution of CBET to changes in forest cover and the difference in total income between CBET and non-CBET households by summarizing our recent studies (Lonn et al. 2018b, 2019). The analysis using forest cover change maps showed that the Chambok CBET contributed to reducing deforestation, but its contribution was not enough to stop net deforestation. This finding is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that community-based forest management in general was effective in conserving forests. First, according to a meta-analysis of case studies in 40 protected areas and 33 community-managed forests, mostly in tropical America, some in Asia, and one in Africa (Porter-Bolland et al. 2012), the community-managed forests presented lower and less variable annual deforestation rates than protected forests. Second, according to a more recent meta-analysis of 159 studies in Central America and Mexico (Min-Venditti et al. 2017), community-based management was associated with a positive impact on forest cover in 81% cases, whereas protected areas were associated with a positive impact in 66% cases.

While we showed the evidently positive contribution of CBET to forest conservation, CBET seldom contributed to any increase in the income of the local people—ecotourism generated the only US $1.2/month in median comparison. Further, the interview on livelihood change showed the limited contribution of CBET to the livelihood of local people. This may be because Cambodia has witnessed remarkable economic growth since 1998 (Guimbert 2011), and that may provide more employment opportunities. It is notable that the maximum ecotourism income was US $97.5, while the median was US $1.2. This result means there is gross inequality in ecotourism income among Commune members. It is well known that inequality in ecotourism income has a negative impact on ecotourism activities (He et al. 2008; Coria and Calfucura 2012). In the case of Chambok CBET, this inequality depends on the ecotourism-related works that the local people were engaged in and the fact that large incomes were generated only from homestays (Lonn et al. 2019). The revision of ecotourism income distribution may be key to improving the average income of local people.

For archiving the success of CBET, further studies are required to clarify local people’s motivation to conserve forests under CBET. Conceptually, ecotourism motivates local people to conserve forests because ecotourism needs attractive natural resources. However, in our case, the conservation effect may not be derived from ecotourism—because ecotourism made a limited contribution in increasing local people’s income and few felt it had improved their livelihood, it is unlikely to motivate forest conservation. On the other hand, community-based activities for forest management positively contribute to forest conservation, whether or not it includes ecotourism (Min-Venditti et al. 2017; Pandey et al. 2017). Some studies show that tenure security, clear ownership, and/or effective enforcement are important factors affecting the success or failure of community-based forest management (Pagdee et al. 2006; Baynes et al. 2015). Further studies on the effects of these factors are needed to better understand the success or failure of forest conservation under CBET.

Finally, we would like to make some suggestions to enable the future success of the Chambok CBET. First, further efforts toward forest restoration are needed because CBET was effective but could not stop deforestation. Forest cover in the Chambok CBET has continued to decrease. Therefore, any strategy that effectively accelerates forest recovery should be developed. Second, equalization of the ecotourism income is an urgent issue to improve the income of the majority of local people. Currently, only homestay hosts are making a big profit. Thus, there is a need to create new ecotourism-related jobs for those with low incomes, although it is easier said than done.

In conclusion, CBET is effective in forest conservation, but its contribution to increasing the income of local people is limited. To realize the expectation that CBET can harmonize better quality of life for local people with forest conservation, we need to develop new strategies focusing on forest restoration and income equalization.

References

Achard F, Eva HD, Stibig H-J, Mayaux P, Gallego J, Richards T, Malingreau J-P (2002) Determination of deforestation rates of the world’s humid tropical forests. Science 297:999–1002

Ameha A, Nielsen OJ, Larsen HO (2014) Impacts of access and benefit sharing on livelihoods and forest: case of participatory forest management in Ethiopia. Ecol Econ 97:162–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.11.011

Baccini A, Walker W, Carvalho L et al (2017) Tropical forests are a net carbon source based on aboveground measurements of gain and loss. Science 358:230–234

Baynes J, Herbohn J, Smith C et al (2015) Key factors which influence the success of community forestry in developing countries. Glob Environ Chang 35:226–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GLOENVCHA.2015.09.011

Bonan GB (2008) Forests and climate change: forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science 320:1444–1449

Coria J, Calfucura E (2012) Ecotourism and the development of indigenous communities: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Ecol Econ 73:47–55

Das M, Chatterjee B (2015) Ecotourism: a panacea or a predicament? Tour Manag Perspect 14:3–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TMP.2015.01.002

FAO (2015) Global forest resources assessment 2015: how are the world’s forests changing? Rome

Guimbert S (2011) Cambodia 1998–2008: an episode of rapid growth. In: Facets of competitiveness: narratives from ASEAN. World Scientific, Singapore, pp 151–183

Hansen MC, Potapov PV, Moore R et al (2013) High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science 342:850–853. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1244693

He G, Chen X, Liu W et al (2008) Distribution of economic benefits from ecotourism: a case study of Wolong nature reserve for Giant Pandas in China. Environ Manag 42:1017–1025. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-008-9214-3

IPBES (2018) The IPBES regional assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services for Asia and the Pacific. Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Bonn, 612 p

Kiss A (2004) Is community-based ecotourism a good use of biodiversity conservation funds? Trends Ecol Evol 19:232–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TREE.2004.03.010

Lonn P, Mizoue N, Ota T et al (2018a) Biophysical factors affecting forest cover changes in community forestry: a country scale analysis in Cambodia. Forests 9:273. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9050273

Lonn P, Mizoue N, Ota T et al (2018b) Evaluating the contribution of community-based ecotourism (CBET) to household income and livelihood changes: a case study of the Chambok CBET program in Cambodia. Ecol Econ 151:62–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.04.036

Lonn P, Mizoue N, Ota T et al (2019) Using forest cover maps and local people’s perceptions to evaluate the effectiveness of community-based ecotourism for forest conservation in Chambok (Cambodia). Environ Conserv 46:111–117. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892918000462

Min-Venditti AA, Moore GW, Fleischman F (2017) What policies improve forest cover? A systematic review of research from Mesoamerica. Glob Environ Chang 47:21–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GLOENVCHA.2017.08.010

Newbold T, Hudson LN, Phillips HRP et al (2014) A global model of the response of tropical and sub-tropical forest biodiversity to anthropogenic pressures. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 281:1371. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.1371

NIS (2008) Statistical year book 2008. NIS, Phnom Penh

Pagdee A, Kim Y-S, Daugherty PJ (2006) What makes community forest management successful: a meta-study from community forests throughout the world. Soc Nat Resour 19:33–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920500323260

Pandey SS, Maraseni TN, Reardon-Smith K, Cockfield G (2017) Analysing foregone costs of communities and carbon benefits in small scale community based forestry practice in Nepal. Land Use Policy 69:160–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.LANDUSEPOL.2017.09.007

Porter-Bolland L, Ellis EA, Guariguata MR et al (2012) Community managed forests and forest protected areas: an assessment of their conservation effectiveness across the tropics. For Ecol Manag 268:6–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FORECO.2011.05.034

Prachvuthy M (2006) Tourism, poverty, and income distribution: Chambok community-based ecotourism development, Kirirom National Park, Kompong Speu Province, Cambodia. J GMS Dev Stud 3:25–40

R Core Team (2019) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.r-project.org/. Accessed 29 Aug 2019

Rasolofoson RA, Ferraro PJ, Ruta G et al (2017) Impacts of community forest management on human economic well-being across madagascar. Conserv Lett 10:346–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12272

San V, Spoann V, Ly D, Chheng NV (2012) Fuelwood consumption patterns in Chumriey Mountain, Kampong Chhnang Province, Cambodia. Energy 44:335–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENERGY.2012.06.025

Scheffers BR, Joppa LN, Pimm SL, Laurance WF (2012) What we know and don’t know about Earth’s missing biodiversity. Trends Ecol Evol 27:501–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2012.05.008

Sekhon JS (2015) Package ‘Matching’ [www document]. http://dirichlet.mat.puc.cl/web/packages/Matching/Matching.pdf

Stuart EA (2010) Matching methods for causal inference: a review and a look forward. Stat Sci 25:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1214/09-STS313

Sullivan MJP, Talbot J, Lewis SL et al (2017) Diversity and carbon storage across the tropical forest biome. Sci Rep 7:39102

Sunderlin WD, Belcher B, Santoso L et al (2005) Livelihoods, forests, and conservation in developing countries: an overview. World Dev 33:1383–1402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.10.004

Top N, Mizoue N, Kai S, Nakao T (2004) Variation in woodfuel consumption patterns in response to forest availability in Kampong Thom Province, Cambodia. Biomass Bioenergy 27:57–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BIOMBIOE.2003.10.008

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the local authorities, Chambok CBET members, and Chambok Commune members for supporting the study. We are also grateful to the staffs of FA, the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Cambodia based in the provinces and in Phnom Penh, and the Mlup Baitong. A portion of the original content is from Ecological Economics, 151, 62–69, Evaluating the Contribution of Community-based Ecotourism (CBET) to Household Income and Livelihood Changes: A Case Study of the Chambok CBET Program in Cambodia, (2018), with permission for “text extraction” and “reuse of figure” from Elsevier. The other is from Environmental Conservation, 46, 111–117, Using Forest Cover Maps and Local People’s Perceptions to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Community-based Ecotourism for Forest Conservation in Chambok (Cambodia), (2019), with permission for “text extraction” and “reuse of figure” from Cambridge University Press. This work was supported by a grant JPMJRX16F1 from the Research Institute of Science and Technology for the Society (RISTEX) of Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) as part of the Future Earth programs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ota, T., Lonn, P., Mizoue, N. (2021). Contribution of Community-Based Ecotourism to Forest Conservation and Local Livelihoods. In: Yahara, T. (eds) Decision Science for Future Earth. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-8632-3_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-8632-3_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-15-8631-6

Online ISBN: 978-981-15-8632-3

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)