Abstract

The goal of the study is to explore the unemployment challenge for the United Arab Emirates (UAE) youth in comparison with other Gulf countries. The chapter uses multiple data sources to provide a complex analysis of recent dynamics and the current situation of school-to-work transition among Emirati youth. The empirical part of the analysis provides the rear information on actual career paths and challenges for youth to find their first job. Skills shortages and lack of professional qualities are among the frequently named reasons for not getting a job. For young women, such obstacles as family responsibilities and geographical restriction of job search are reported. Young men find jobs much faster than women. The main channels of job search for the Emiratis are personal liaisons and university contacts.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The Gulf countries have one of the highest proportions of youth (people under 25 years old) in the population: one-fourth to one-half (Abdelgadir, 2020). Therefore, youth accounts for 25% of the population in Qatar, 34% in the UAE, 35% in Bahrain, 40% in Kuwait, 46% in Saudi Arabia, and 50% in Oman (Oxford Business Group, 2016). Such population structure creates challenges for national economies to accommodate all young people in the labor market. Economic growth and stability depend on youth employment. However, high records of youth unemployment have increased the risk of political instability and other social concerns in the Arab region (Farzanegan & Gholipour, 2021).

Youth unemployment is one of the biggest issues for the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region as it has the world’s highest youth unemployment rate, standing at 27.2% in the Middle East and 29% in North Africa (Oxford Business Group, 2016). At the same time, youth unemployment rates in Gulf countries vary from the highest rate of 29% in Saudi Arabia to the lowest rate of 1.5% in Qatar (Abdelgadir, 2020).

This chapter contributes to the discussion of the youth unemployment challenge by shedding light on the situation in the UAE. Total youth unemployment increased from 6% in 2000 to 7.5% in 2019 (according to national statistics: FCSA, 2022). A closer look at the statistics by gender discovers that these are mainly young females who contribute to the unemployment rate in the country (see Fig. 30.1 below). According to the official statistics, the unemployment rate among females reached 12.8% in 2019, while the unemployment rate among males was only 5.7%. This pattern could be observed in other Gulf countries as well. For example, in Saudi Arabia, the female youth unemployment rate is twice higher for women (46.9%) compared to the male youth unemployment rate (18.4%) (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2018). Figure 30.1 also demonstrates the importance of the unemployment challenge specifically for youth in the UAE since the unemployment rate among the population aged 25 and above is very low: 1.2 for males and 5.1 for females.

Interestingly, the gross enrollment rates in higher education increased tremendously during the last ten years from 15.6% in 2008 to 37.1% in 2017. The numbers are even higher for females, with an increase from 27.7% in 2008 to 45.3% in 2017 (UNESCO, 2020). It should be noted that education and training are free for nationals in the UAE. Does it mean that more and more graduates from higher education institutions will stay without jobs? What are the main challenges that graduates face recently while searching for their first jobs in the UAE? Why is the unemployment rate higher for females than for males? How much does it relate to traditional Muslim culture? Can gender differences in job opportunities explain this gap in unemployment rates? These are the research questions that this chapter tries to answer below.

The chapter is organized as follows: first, it sheds light on the country’s labor market background. Second, the chapter provides an analysis of the current challenges of university graduates in their first job search. This analysis is based on the alumni survey, conducted in 2019 at the UAE University. Third, the chapter investigates labor market participation of Emirati youth based on the empirical data of Monitoring of Emirati Youth, collected in 2017–2018.

2 Country Background and Labor Market of the UAE

Gulf countries have oil-rich developing economies that faced fast transformation from traditional societies to modern societies along with digitalization on most of the life spheres. The introduced policies and educational reforms since the beginning of the 2000s positively impacted human development in the country. Thus, Human Development Index (HDI) in Gulf countries significantly increased within the last 30 years, which put the countries in the very high human development category—Bahrain at 44th out of 189 countries, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates are ranked 45th and 31st in HDI, Saudi Arabia at 40th, and Kuwait at 64th place in the world (Human Development Report, 2020).

According to the World Bank data, the rate of labor force participation rate for the whole population of the UAE grew from 74.5% in 1997 to 81% in 2016 (World Bank, Data Bank, 2022). Importantly, the employment to population ratio was also growing from 75% in 2001 to 78–79% in the latest years. Employment rates for males were picking even at 90–91% in 2016–2017 (see Fig. 30.2 below). The visible drop in all the employment rates in 2020 could be explained by the economic crisis generated by the COVID-19 lockdown.

Employment to population ratio for ages 15–24 and 15 + by gender, 2001–2019 (Source World Development Indicators. Data Bank. World Bank. ILOSTAT database, Data retrieved on February 8, 2022Footnote

https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&series=SL.EMP.1524.SP.FE.ZS&country=ARE#.

)The UAE labor market has few peculiarities and gender differences in employment/unemployment rates are one of them. The gap in employment rates between males and females is enormous since women are only half-active in comparison with men. At the same time, it is fair to note that the female employment rate went up from 34% in 2001 to 48% in 2017, according to the ILO estimations (World Bank, Data Bank, 2022). The female youth employment rate also increased within the last twenty years but not very much, from 23.6% in 2021 to 30.7% in 2016. The lower rates of youth employment could be explained by still continuing the education process at the age of 15–24.

Another UAE labor market peculiarity is a significant difference in labor participation rates of nationals and non-nationals. According to the latest studies, Emiratis comprise only 8–10% of the total workforce (De Bel-Air, 2018; Gonzalez et al., 2008; Poplavskaya & Karabchuk, 2018; Sönmez et al., 2011). This phenomenon is defined by the population structure in which the expatriates’ share reaches 85% (FCSA, 2022).

There are significant distinctions in the employment behavior of nationals and non-nationals. Most Emiratis tend to work in government organizations, and non-nationals used to hold working positions in private companies. At the end of the 2000s, local and federal government organizations employed nearly 90% of the working nationals and only 15% of foreign workers got positions in the public sector (NBS, 2009). The private sector was traditionally dominated by expatriates. Thus, in 2013, 73% of expatriate workers had a position in commercial companies and only 8% of all employed Emiratis worked for private firms (De Bel-Air, 2018). However, currently, the situation has been changing. The UAE government encouraged Emirati nationals to seek jobs in the private sector by introducing several initiatives, however, they did not prove to be much efficient (Dhakal et al., 2018). But by 2016, already 78% of all employed Emiratis were working at government organizations which are 12 percentage points less than in the 2000s. It means that more and more Emiratis work with private companies. It might be a sign of raising competitiveness between nationals and non-nationals and slow reorientation process toward private sector among national employees.

Importantly, these are exactly young males and females who are interested to open their own business and become entrepreneurs or being employed in the private sector. Since the job opportunities in the public sector became scarce, the fresh graduates are more often forced to enter the private sector doors.

3 Youth challenges in the Labor Market of the UAE

In 2013, the UAE was rated as the best country to live and work in by young Arabs in the region (The National News, 2013). However, there are not many publications dedicated to the UAE youth, their challenges, school-to-work transition, their values, lifestyles, and working behavior.

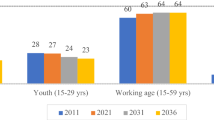

Despite the increased share of the youth enrolled in tertiary education, young people from Arab countries often face difficulties with the transition from education to employment, and the UAE is not an exception (Gonzalez et al., 2008; Sfakianakis, 2005; Sultana, 2014; World Economic Forum, 2014). The previous research showed that the internship programs for the young Emiratis did not always result in actual work placement (Ahmed, 2003). The most significant reason for the increase of Arab unemployment rates is the continuous and extensive growth in the number of young Arab labor forces entering the labor markets annually, and Arab economies cannot provide sufficient job opportunities to face them (ILOSTAT, 2021; MOE Annual report, 2019). In other words, the labor market supply exceeds the labor market demand. If this growth and employment speed continue, youth unemployment will remain in the Arab region until 2040 (MOE Annual report, 2019).

Figure 30.3 demonstrates the ILO modeled estimations of unemployment rates among youth and total population separately for males and females (ILOSTAT, 2021). The female youth unemployment rate reached the highest level in 2020 after COVID-19 and equals to 16.6% while the unemployment rate among young males remains quite stable and fluctuates around 6%, even during the pandemic crisis years did not exceed 6.7%. Similar significant differences could be observed for the total unemployment rates between men and women in the UAE. However, the gender gap in youth unemployment rates (10 percentage points) is significantly higher than the gender gap in total unemployment rates (5.1 percentage points). It is important to highlight that the total unemployment rate in the UAE is extremely low at 2–3%, but it is quite feasible for the youth (9%). The low rates of total unemployment could be explained by the lower proportion of women in the total population, they comprise only one-third of the people residing in the UAE. The female/male ratio among youth is close to equal shares, the contribution of female unemployment is more significant in the total numbers.

(Source World Development Indicators. Data Bank. World Bank. International Labour Organization. ILOSTAT database, Data retrieved on February 8, 2022Footnote

https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&series=SL.EMP.1524.SP.FE.ZS&country=ARE#.

)Unemployment rates for ages 15–24 and 15 + by gender, 2001–2019

A key factor that accounts for a high level of unemployment among young UAE citizens is the youth’s preference for jobs in the public sector. Emiratis used to work exclusively in government organizations, and such a disposition prevents them from the search for decent jobs in private firms. These preferences for public sector jobs over private sector jobs are driven by better compensation packages and benefits in the UAE. The nature of public sector employment is less demanding (in terms of working hours and accountability), safer, and better paying than the private sector (Abdelgadir, 2020). But the government cannot keep hiring young graduates in the public sector at the same speed as the population growth, since the government resources are limited. Very often to obtain such a job, a person needs ‘wasta’ (intercession or influence) since the competition is very high for such positions (Al-Waqfi & Forstenlechner, 2012; Aftadilian, 2017).

While the private sector needs more experienced specialists for less attractive packages, also employers expect them to have a high level of skills, including leadership and communication. And abilities, skills, and habits of the young Emiratis often do not fit into the rapidly evolving sectors of the UAE knowledge economy. This is another reason for rather high unemployment rates. The fresh graduates often do not have enough either technical skills (knowledge of information technology and services, industrial skills, research, and critical thinking skills) or soft skills (communication skills, interpersonal and customer relations, and work ethics), which is a sign for the employers that they are not ready to perform their jobs efficiently (Ahmed, 2003). That is why many employers do not believe that a young Emirati with a degree from a university in the Gulf has the exquisite skills for a job in private companies (Aftadilian, 2017).

Moreover, the level of work experience is rather low among the young Emiratis if compared with their expatriate counterparts. As the idea of joining jobs (especially low paid) at high school or college is not very popular among Emiratis as it is not much supported by the families. This problem of lack of any work experience, that is a common requirement from employers, was mentioned by the alumni of the universities (UAE University employability studies conducted in 2020–2021).

And despite all these facts, the Emirati youth often have unrealistic expectations related to working hours, job title, and compensation, as well as show a low level of loyalty to the companies (Ahmed, 2003; Gonzalez et al., 2008). Contrariwise, the organizations, either public or private ones, stay to be more interested to recruit foreigners on the working positions, as they cost less, have more experience, and are better equipped with practical skills (Al-Waqfi & Forstenlechner, 2012; Burden- Leahy, 2009; Gonzalez et al., 2008; Samier, 2015). The face-to-face interviews with the graduates showed the same results, the female graduates who have BA degrees do not want to work if the salary is below 15,000 AED (UAE University employability studies conducted in 2020–2021). Another study confirmed that national female youth are motivated by pay rewards and it was suggested that the GCC policymakers should consider the pay-productivity link and its implications for human resource management at the organization level (Mina, 2021).

The youth’s ability to plan their livelihood, access information about vacancies, and choose between available occupations on the labor market also plays an important role (Sultana, 2014). Marked abilities help to manage important life transitions of youth from the educational to working stage, and cope with the complexity and uncertainty of the adult world. However, in some countries, the youth does not have such abilities and face more difficulties with the transition. In the United Arab Emirates, the situation with planning the future among the youth was acknowledged to be critical. Due to the results of the Arab Knowledge Report launched in 2010–2011, the average score on the future-planning scale for Emiratis reached only 4.72, when the required minimum was equal to 12.5. This was regarded as a sign of poor career drive motivation among the youth in the UAE (UNDP, 2012).

Career aspirations are very much linked with the cultural values and work values in society. On the one hand, the UAE used to be a collectivistic society, where the values of religion, family, traditional social norms, hierarchy, distinct power roles, dependence on the groups, and important others dominate (Lambert et al., 2015; Uchida & Ogihara, 2012). And a recent study of the UAE university students confirmed such a collectivistic orientation, whereby well-being was considered a state-generated not through the self, but through and with the extended family, siblings, and friends (Lambert & Pasha-Zaidi, 2014a, 2014b). On the other hand, at work Emirati youth have appeared to be more individualistic than earlier generations, scoring low on long-term commitment and loyalty to the social group from which individuals belong (Whiteoak et al., 2006).

Finally, it is worth mentioning that young Emiratis do not worry much about their future. The UAE is one of the countries with the highest levels of happiness, showing quite low levels of negative feelings among the citizen (Helliwell et al., 2017; Lambert et al., 2020; Poplavskaya & Karabchuk, 2018). The youth is not an exception as 94% of young Emiratis generally feel very or rather happy, and 84% of them enjoy their lives most or almost most of the time (Poplavskaya & Karabchuk, 2018). A recent study showed that in general, Emiratis are not worried about their future (Lambert et al., 2020). One of the key explanations for that is that the UAE government takes a lot of actions and develops policies to help their citizens to find good jobs.

3.1 Government Role and Social Policies for the Youth

In such an environment, where the flow of migrants is so intensive and the level of unemployed nationals is high, the government is trying to create special programs for promoting the employment of young nationals in the government and private sectors (Gonzalez et al., 2008). One of such programs is called Emiratization. The program is aimed at reducing the reliance on foreign labor (especially in high-skill fields and targeted sectors of the economy), training nationals in skills that are competitive both nationally and internationally, lessening unemployment of nationals, attracting youth on the labor market, making private sector more appealing for youth, and increasing the share of professional and skilled workers in growing sectors of the economy. The focus is on the development of two spheres of youth life: education and work, as well as on binding them. In the first sphere, the government suggests expanding the higher education facilities, connecting workforce demands and educational outcomes, concentrating on educational results.

To facilitate the successful transition from education to work the government implemented working training programs, internships in private and state organizations, career counseling and guidance, dialogue between private and public sectors, workforce and education institutions. In the sphere of work, the main actions were focused on implementing quotas, compliance mandates, employment policy levers (such as minimum wage requirements, taxes on businesses importing labor), taxes on salaries of imported labor, and higher visa and residency processing requirements, etc. (Al-Fakhri, 2004; United Arab Emirates Ministry of Information and Culture, 2006).

According to sustainable development goal 8 (SDG 8), it is significant to “promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all” (United Nations, 2021). Based on that, the UAE government highlighted the importance of the reduction of unemployment of youth through the “development-oriented policies that support productive activities, decent job creation…”, and aimed to provide “full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men including young people and persons with disabilities by 2030” (Ministry of Human Resources and Emiratization, 2021). Moreover, to increase the number of Emirati youth working in the private sector, the UAE government recently announced to ensure 10% of the Emirati workforce on skilled roles in private companies within the next five years (Tolley, 2021).

To sum up, the scarcity of working positions in the public sector and rising competition in the private sector are becoming a more tangible hindrance for the young nationals to find an appropriate working position on the market. Moreover, the private sector continues to be the main recruiter of non-national workers, but the public sector is also changing toward hiring more foreigners. Under such conditions, it is crucial to explore the national youth labor market participation patterns.

4 Monitoring of Emirati Youth: Labor Market Participation Analysis

4.1 Data and Methodology

For the empirical analysis of employment patterns among Emirati youth, we use the data, collected within the project of Monitoring of Emirati Youth (MEY) in 2018. The survey investigated sociodemographic characteristics and labor market participation of Emirati youth as well as their attitudes to health, marriage, fertility, migration, politics, etc. The sample comprised 740 respondents aged 18–35 years old. The mode of survey data collection was face-to-face interviews administered with the help of a printed questionnaire.

Young women in the final sample outnumbered men, as 82% of the respondents were female. On the one hand, this sample bias is a limitation for the study as it affects for the results. On the other hand, the sample does represent the current Emirati youth as a huge proportion of Emirati men in this age group are missing from the country due to their education abroad.

More than half of respondents lived in Abu Dhabi (57%) (the largest emirate by the size of the national population), 11% in Fujairah, 10% in Ajman, and the rest live in other emirates. 54% of respondents live in cities or big cities, 29% live in towns, and only 17% in villages. As for the socioeconomic characteristics, 13% of respondents evaluated their family income as low, 56% as normal and 31% as high. Only 4% of Emirati youth live independently from their parental family, others live with their parents or parents-in-law. The distribution by education showed that 62% had higher educational attainment (Bachelor’s, Master’s or Doctoral degree), and the rest had higher school certificates and were in the process of receiving their university or vocational education degrees. 23% of the respondents reported being married. 18% of married youth had children (two children on average).

In terms of employment status, 20% of the respondents had a paid job and 10% reported being unemployed. We follow the ILO definition of unemployment and identify those who are unemployed when a person does not have a job, is searching for a job, and is ready to start the job within the next two weeks. This number is pretty in line with the official statistics on youth unemployment for 2018. Among the employed Emirati youth, 78% were working in the government sector, 20% of youth work for a private company, and only 2% are involved in a family business. 44% of employed youth had a permanent work contract, 42% had a fix-term contract, 10% worked unofficially (by oral agreement) and 4% reported being self-employed.

4.2 Labor Market Participation of Emirati Youth

Five employment status groups of Emirati youth were identified from the data: students, employed students, employed non-students, unemployed youth, and non-active youth (who reported not studying, not working, and having no wish to get a job). Non-working students comprised 62% of the sample, 5% of the youth were working while studying, 14% of youth were employed Emiratis who had finished their education, 10% were unemployed youth, and the rest 9% were classified as non-active (Table 30.1).

The first group of Emirati youth is the most numerous and it represents students, who do not have a paid job. It is the youngest group in the sample, most of them are not married. The next group also represents students, but they are employed. The men comprise 1/3 of that group, which is three times more than among not employed students. This result is in line with the fact that the number of young Emirati females is exceeding the number of young Emirati males in higher education institutions (Abdulla & Ridge, 2010; Gonzales et al., 2018). Since 2008, over 70% of Emiratis pursuing undergraduate degrees have been women (Abdulla & Ridge, 2010; Fox, 2018; Samier, 2015). Thus, Emirati females account for 71% of students in the largest UAE University (Gonzales et al., 2018). Among the HCT Emirati graduates, 56% were females. And even among the Emirati graduates from the private institutions, 64% were females (Gonzales et al., 2018). Most Emiratis men study abroad or are engaged in the army or police academic institutions (Ahmed, 2003).

The third group, employed non-students, is the oldest group in the sample. Half of them are males. Half of the employed non-students are married and have children, 17% of the employed non-students are living independently from their older parents, which is the highest percentage among the employment status groups among the youth.

Unemployed and non-active youth comprise 1/5 of the sample. It is important to compare these two groups as they differ by the desire and readiness to be involved in the labor market. There are two times more married young people among the non-active than among the unemployed. These are mainly female homemakers who chose not to work outside the household since more of them have children to take care.

Interestingly, these employment status groups do not differ significantly by geographical area and income. Despite the expectations of lower income for those who are unemployed or non-active, the analysis showed that income does not correlate with the employment status of Emirati youth. On average, the youth evaluated their income as of 6.5 on the 10-point scale (Table 30.2).

4.3 The Transition from School to Work and Employment Trajectories of Emirati Youth

What ways to find a job do Emirati youth use? The empirical MEY data of 2018 allows discussing how the current youth are looking for jobs in the UAE. The analysis of MEY data demonstrated that the most popular way for unemployed youth was to send CVs to the companies (42% of students and 51% of unemployed). However, most of the employed youth specified that they got their jobs with the help of personal liaisons such as family and friends (44% of employed non-students and 43% of employed students). Another way to obtain employment positions for students was via help from the university (31%). And the youth, who completed their studies, found their jobs with the help of the government job center and job placement (25%).

It seems that these channels of job search are more efficient than sending CVs to companies. It means that the official mechanisms of finding jobs through CV applications are not efficient for the Emirati youth. The possible explanations of that could be that (1) the CVs of the youth are not strong enough to compete with other candidates; (2) high wage expectations of the youth; (3) high costs for the companies and organizations to recruit nationals; (4) high competition for the jobs from inside and outside the country; (5) lack of professional and soft skills acquired by Emirati youth, etc. This result is in line with the previous research in this field, which showed that younger UAE nationals see the utility of ‘wasta’ as important (Whiteoak et al., 2006).

Another series of alumni studies, conducted by the UAE University, demonstrated that indeed the process of job search is more time-lengthy for women. On average, it takes 9–12 months for graduate females to find a job, while it is 3–6 months for males. Among those who are employed, 90% declared that they found their first job within two years after their graduation. And among the unemployed female graduates, about 50% have been looking for a job for more than six months.

If we look at the work trajectories of Emirati youth, we will find the following interesting information. 80% of employed young Emirati men and women work in the government sector. Importantly, only half of employed youth have permanent contracts. Compared to other developing countries in the MENA region, the share of youth working without written contracts is very low (10%), and they are mainly full-time students who combine their studies with work. The self-employed youth is the least numerous group: only 4% of youth in the sample have their own business. Entrepreneurship is one of the ways to engage unemployed graduates into the labor market and Emirati youth both males and females have great opportunities for start-up funds from the government.

The time of the working day also differs depending on the employment status of the youth. More than half of the employed non-students work regular 8 h per day or even more. In accordance with the UAE legislation, standard working hours are 40 h per week (8 h per day). Such workday is also common for 44% of the employed students. The hours spent on work correlate with the salaries. On average in 2018, employed youth aged 18–34 (non-students) earned approximately 18,544 AED per month while those who combined studies and work earned about half of the sum—9977 AED per month.

About one-fourth of employed youth work as managers and highly qualified specialists (CEOs, top-managers) or professional and technical specialists (doctor, teacher, engineer, artist, accountant, nurse). As for the economic activity, 25% of employed youth are engaged in the education sector, 15% work in finance; 10% of employed youth work in.

The data shows that employed Emirati youth start their working career approximately at the age of 22, and the employed students find jobs at the age of 20. It is important to note here that the early start of the working life does not mean that the first job matches their education profiles. Thus, only 55% of working students confirmed that their current job does match their educational qualifications. Among those who finished their studies and are working full-time already 66% declared that their job matches their professional skills received at the university. There are no significant differences in job satisfaction and worries about losing their jobs between employed students and non-students. The average level of job satisfaction for all the employed Emirati Youth is 6.8 (out of 0 possible points). And the level of worry is low and equals 2.4 (on the 10-point scale) (Table 30.3).

5 Conclusions

This chapter is dedicated to the discussion of such important challenges like youth unemployment in the UAE as a case study of one of the GCC countries. The numbers of those young people who seek for jobs and are ready to start them are sharply increasing in all GCC countries reaching the highest number in Saudi Arabia at 29%, like in many MENA region countries. In the UAE, the growth was rather smooth: from 6% in 2000 to about 8–9% in recent years. The UAE peculiarity is that there is a significant gender gap in unemployment rates. Young females suffer from unemployment much more than males, the unemployment rates equal to 6% for males and 16% for females.

The reasons for this phenomenon include (a) better educations of the males (since most of them study abroad); (b) guaranteed placement for the young men who choose a career in the police and army; (c) inability to travel more than 50 km from the house for work among the females; (d) family restrictions to combine work and parental duties for women; (e) lack of work experience and necessary skills to pursue a job among fresh female graduates from the UAE higher education institutions; (f) wage miss-expectations and lack of work ethics among Emirati female graduates and more (outcomes are based on the series of Employability studies conducted by the UAE University in 2020–2021).

In general, college students may be prepared academically, but they may lack soft skills, such as analytical reasoning, interpersonal skills, self-discipline, time, money, resources, and communication and technology skills (Bouland-van-Dam et al., 2021). Indeed, half of the unemployed alumni mentioned the necessity of extra qualifications and skills as one of their unemployment factors (Employability studies conducted by the UAE University in 2020–2021). Narrowing this gap between the skills employers seek and the skills applicants possess remains a challenge for businesses, higher education, students, and the government.

Previous study of Emirati youth showed that having a job contributes to positive aspects of well-being (feeling happy and not feeling sad), while unemployment is connected with feelings of loneliness and depression (Poplavskaya & Karabchuk, 2018). However, combining work with university studies seems to have a twofold effect on young Emiratis as it leads to less life enjoyment and more loneliness, but decreases depressive symptoms among the youth.

The empirical study used in this chapter demonstrated the possible career paths and difficulties in the transition from school to work. If we look at the youth category of age 18–34, we will see that most of them are still students. Moreover, male students more often take their studies abroad compared with female students, who get their higher education in the UAE (mostly in public universities). After the age of 22, the Emirati youth find their first jobs. It is important to note that about 96% of the university degree holders do actively search for jobs after graduation (Employability studies conducted by the UAE University in 2020–2021). The main channels of job search for the employed Emiratis were personal liaisons and university contacts while most unemployed graduates were trying to find jobs via submitting their CVs or by registering at the national employment service.

The rate of employment is much higher among male youth than among female youth, which could be also explained by family and childcare duties that women traditionally fulfill in the Arab region. 80% of the employed youth work in the government sector, but less than a half of employed youth have a permanent contract.

References

Abdelgadir, S. (2020). Challenges and potentiality of GCC countries towards achieving sustainable economic growth: Analytical framework. European Journal of Business and Innovation Research, 8(5), 23–37.

Abdulla, F., & Ridge, N. (2010). Where are all the men? Gender, participation and higher education in the United Arab Emirates. In B. Lamine (Ed.), Towards an Arab higher education space: International challenges and societal responsibilities (pp. 125–136). UNESCO. Regional Bureau for Education in the Arab States. Beirut.

Aftandilian, G. (2017). Can Egypt lead the Arab world again? Assessing opportunities and challenges for U.S. Policy. USAWC Press. https://ssi.armywarcollege.edu/pubs/display.cfm?pubID=1352 (letöltés ideje:2018. 08.05.)

Ahmed, O. S. (2003). Assessing relevance of work placement schemes of higher education institutes in the UAE. CLMRI, National Human Resource Development and Employment Authority, Careers, Skills, and Training Survey Series №3, Dubai, UAE: CLMRI.

Al-Fakhri, Jassem, J. (2004). The demographic structure of the GCC states. The Gulf in a year—2003 (pp. 68–80). Gulf Research Center.

Al-Waqfi, M., & Forstenlechner, I. (2012). Of private sector fear and prejudice. Personnel Review, 4(5), 609–629.

Burden- Leahy, S. M. (2009). Globalisation and education in the postcolonial world: The conundrum of the higher education system of the United Arab Emirates. Comparative Education, 45(4), 525–544.

Bouland-van Dam, S. I., Oostrom, J. K., De Kock, F. S., Schlechter, A. F., & Jansen, P. G. (2021). Unraveling leadership potential: Conceptual and measurement issues. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 30(2), 206–224.

De Bel-Air F. (2018). Demography, Migration, and the Labour Market in the UAE, Explanatory Note No. 1/2018, Gulf Labour Markets, Migration and Population Programme (GLMM) of the Migration Policy Center (MPC) and the Gulf Research Center (GRC), http://gulfmigration.eu

Dhakal, S. P., Connell, J., & Burgess, J. (2018). Inclusion and work: Addressing the global challenges for youth employment. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, 37(2), 110–120. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-12-2017-0290

Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). (2018, September 13). Middle East and Africa economy: Youth unemployment remains a challenge in the gulf. ViewsWire. https://www.proquest.com/wire-feeds/middle-east-africa-economy-youth-unemployment/docview/2135682776/se-2?accountid=62373

Farzanegan, M. R., & Gholipour, H. F. (2021). Youth unemployment and quality of education in the MENA: An empirical investigation. In M. S. Ben Ali (Eds.), Economic development in the MENA region. Perspectives on development in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66380-3_5

Federal Competitiveness and Statistical Authority (FCSA). (2022). FCSA statistics online. https://bayanat.ae/en/Data?query=population. Accessed 16 February 2022.

Federal Competitiveness and Statistical Authority (FCSA), Dubai Statistic Center—Labour Force Survey 2019.

Fox, K. F. (2018). Leveraging a leadership development framework for career readiness. New Directions for Student Leadership, (157), 13–26.

Gonzalez, G., Karoly, L. A., Constant, L., Goldman, C. A., & Salem, H. (2008). Facing human capital challenges of the 21st century: Education and labor market initiatives in Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates (Vol. 786). Chapter 4. Rand Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG786.html

Gonzalez, G., Karoly, L., Constant, L., Salem, H., & Goldman, C. (2018). Facing human capital challenges of the 21st century: Education and labor market initiatives in Lebanon. Oman, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates: Executive Summary. https://doi.org/10.7249/mg786.1

Helliwell, J. F., Huang, H., & Wang, S. (2017). Statistical appendix for ‘The social foundations of world happiness’. Chapter 2: World Happiness Report 2017. https://s3.amazonaws.com/happiness-report/2017/StatisticalAppendixWHR2017.pdf

Human Development Report. (2020). http://hdr.undp.org/sites/all/themes/hdr_theme/country-notes/KWT.pdf

ILOSTAT. (2021). Labor force survey data. Youth unemployment rate and labor force participation rate by sex and age from 15–24 in 2019. Source: ilo.org/shinyapps/bulkexplorer40/?lang=en&segment=indicator&id=UNE_DEAP_SEX_AGE_RT_A

Oxford Business Group. (2016). Meeting the needs of the GCC region’s growing youth population. The Kuwait Report 2016. https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/analysis/dividend-or-liability-meeting-needs-region%E2%80%99s-growing-youth-population-2

Lambert D’raven, L., & Pasha-Zaidi, N. (2014a). Happiness in the United Arab Emirates: Conceptualizations of happiness among Emirati and Other Arab students. International Journal of Happiness and Development, Inderscience Enterprises Ltd, 2(1), 1–21.

Lambert D’raven, L., & Pasha-Zaidi, N. (2014b). Happiness strategies among Arab university students in the United Arab Emirates. The Journal of Happiness and Well-Being, 2(1), 131–144.

Lambert, L., Pasha-Zaidi, N., Passmore, H.-A., & York Al-Karam, C. (2015). Developing an indigenous positive psychology in the United Arab Emirates. Middle East Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(1), 1–23.

Lambert, L., Karabchuk, T., & Joshanloo, M. (2020). Predictors of life satisfaction in the United Arab Emirates: Results based on Gallup data. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00873-3

MOE Annual Economic Report 2019. 27th Edition. https://u.ae/en/information-and-services/jobs/uae-workforce

MoHRE (Ministry of Human Resources and Emiratisation), Foreign labourers employed in the UAE private sector by activity, 2016. http://www.mohre.gov.ae/en/data-library.aspx

Mina, W. (2021). Youth Unemployment and Productivity-Pay in the GCC Countries. In Macroeconomics [Working Title]. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.99975

Ministry of Human Resources and Emiratization. (2021). About Sustainability Development Goals. https://www.mohre.gov.ae/en/about-us/ministry-sustainability-efforts.aspx

NBS (National Bureau of Statistics), Labor Force Survey 2009 (Abu Dhabi: NBS, 2011).

Poplavskaya, A., & Karabchuk, T. (2018). The subjective wellbeing of Emirati youth: Does work really matter? Middle East Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(1), 126–141.

Samier, E. (2015). Emirati women’s higher educational leadership formation under globalisation: Culture, religion, politics, and the dialectics of modernisation. Gender and Education, 27(3), 239–254.

Sfakianakis, J. (2005). An overview of the gulf economies: Challenges and prospects in a global marketplace. Gulf Yearbook 2004. Gulf Research Center, pp. 79–92.

Sönmez, S., Apostolopoulos, Y., Tran, D., & Rentrope, S. (2011). Human rights and health disparities for migrant workers in the UAE. Health and Human Rights, 13(2), E17-35.

Sultana, R. G. (2014). Livelihood planning and career guidance in Palestine and the broader MENA region. International Review of Education, 60(2), 177–197.

Tolley, G. (2021, September 12). UAE private sector given five years to make 10% of workforce Emirati. The National News. Accessed February 20, 2022 https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/government/2021/09/12/uae-private-sector-given-five-years-to-make-10-of-workforce-emirati/

The National News. (2013, April 10). UAE best place to live or emulate, says Arab youth survey. https://www.thenational.ae/uae/uae-best-place-to-live-or-emulate-says-arab-youth-survey-1.599182

Uchida, Y., & Ogihara, Y. (2012). Personal or interpersonal construal of happiness: A cultural psychological perspective. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(4), 354–369.

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). (2012). The Arab knowledge report 2010/2011. Preparing future generations for the Knowledge Society. Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum Foundation and UNDP-Regional Bureau for Arab States.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics database. (2020). Gross enrolment ratio for tertiary education. http://tcg.uis.unesco.org/4-3-2-gross-enrolment-ratio-for-tertiary-education/ Retrieved 18 February 2022

United Arab Emirates Ministry of Information and Culture, UAE Yearbook 2006, Abu Dhabi: Ministry of Information and Culture, 2006. As of July 21, 2008. http://www.uaeinteract.com/uaeint_misc/pdf_2006/index.asp#year

United Nations. (2021). Sustainable development goals. https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal8

Whiteoak, J. W., Crawford, N. G., & Mapstone, R. H. (2006). Impact of gender and generational differences in work values in an Arab culture. Thunderbird International Business Review, 48(1), 77–91.

World Bank. (2022). Unemployment, youth total (% of total labor force ages 15–24) (modeled ILO estimate)—Middle East & North Africa. Accessed on February 20, 2022, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.1524.ZS?locations=ZQ

World Economic Forum. (2014). Rethinking Arab employment: A systemic approach for resource-endowed economies. Retrieved from http://reports.weforum.org/rethinking-arab-employment/

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Poplavskaya, A., Karabchuk, T., Shomotova, A. (2023). Unemployment Challenge and Labor Market Participation of Arab Gulf Youth: A Case Study of the UAE. In: Rahman, M.M., Al-Azm, A. (eds) Social Change in the Gulf Region. Gulf Studies, vol 8. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-7796-1_30

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-7796-1_30

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-7795-4

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-7796-1

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)