Abstract

Background and aims

Exercise addiction may be conceptualized as a behavioral addiction in which a person develops an unhealthy obsession with exercise and physical activity. While exercise addiction is not a formally recognized disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual or the International Classification of Diseases, it has been studied and connected to both personal and situational factors. Perfectionism is a feature that has been strongly linked to exercise addiction. The objective of this systematic literature review, performed by following the PRISMA protocol, was to examine relationships between exercise addiction and perfectionism while also considering the subdimensions of perfectionism in different groups.

Methods

Three databases (PsycINFO, PubMed/Medline, and SPORTDiscus) were examined. Sixty relevant articles were identified, of which 22 met inclusion criteria.

Results

The findings substantiate that perfectionism and its dimensions are weakly or moderately related to exercise addiction. This relationship has been observed in adults, adolescents, athletes, and patients with eating disorders. Of the 22 studies examined, only one did not identify an association between perfectionism or its subdomain(s) and exercise addiction. However, in most studies, the common variance between perfectionism and exercise addiction is relatively small, raising questions regarding the clinical relevance of the relationship.

Conclusion

Perfectionism is related to exercise addiction, but the strength of the relationship varies in different circumstances, which should be examined in future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In general, exercise improves physical as well as mental health [1]. There is, however, a point at which exercising can be detrimental. Negative impacts may include damage to one’s physical or mental health. Such negative impacts may occur when individuals exhibit poor control over their exercise regimen and engage in excessive amounts of exercise that interfere with other essential aspects of their everyday lives, resulting in adverse physical, psychological, and/or social consequences [2]. Such dysfunction may share features with addictions, including those to gambling or gaming. Therefore, the term “exercise addiction” has been used [2].

Exercise addiction has been described as involving poor control over one’s exercise behavior such that exercise is continued despite adverse consequences. Exercise addiction may exhibit features of addictions involving salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal conflict, and relapse [3, 4]. Exercise addiction has been described in over 1000 research publications [5]. Scholars have used different terms, such as “exercise dependence,” “compulsive exercise,” and “obligatory exercise” [6]. Addiction has been described as a behavioral process that results in changes of emotions (i.e., feeling guilty when not engaging in the activity and/or relief when engaging excessively) that become uncontrollable, imperative, and compulsive [7]. While some have argued that the term exercise addiction may be the most valid [3, 8, 9], the term does not appear in diagnostic manuals (e.g., the DSM-5 [10] or the ICD-11 [11]). As such, more data on the extent to which excessive and interfering patterns of exercise constitute a disorder or an addiction are needed.

Although many aspects of exercise addiction have been studied (onset, prevalence, maintenance, progression, etc.), investigations of personality-related factors have been described as being particularly relevant [12]. Of personality-related characteristics, perfectionism has been strongly associated with exercise addiction [12]. As obsessions and compulsions are often linked to perfectionism [13], this finding raises the possibility of alternate conceptualizations of exercise addiction including an obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorder.

Perfectionism involves tendencies to set excessively high personal standards, strive constantly for excellence and overambitious goals, and/or be overly critical of oneself [14,15,16,17]. As such, perfectionism has been described as maladaptive and related to psychopathologies. Nonetheless, perfectionism has also been associated with positive qualities. For example, perfectionism may reflect tendencies to improve performance, experience satisfaction, and/or achieve goals [18,19,20,21].

Hewitt and Flett [22] have described three dimensions of perfectionism: [1] self-oriented perfectionism (SOP; setting unrealistic standards for the self), [2] other-oriented perfectionism (OOP; setting unrealistic expectations of other people), and [3] socially prescribed perfectionism (SPP; believing that other close individuals expect perfect performance from them) [16, 22]. The three domains may be assessed with the Hewitt-Flett Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (HF-MPS), which is among the most commonly used instruments to measure perfectionism [17, 23, 24]. Two other tools, Cox’s Short Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (Cox MPS) and the Children and Adolescent Perfectionism Scale (CAPS), are based on the HF-MPS. The Cox MPS differs from the HF-MPS in the number of items. While the HF-MPS uses 15 items for to assess each of the three domains, the Cox MPS uses 5 for each domain, thus reducing respondent burden [16, 23]. The CAPS was developed to assess perfectionism in children and adolescents and measures two domains, SOP and SPP [25]. Another assessment of perfectionism, the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMPS), includes other dimensions: (1) concern over mistakes, (2) personal standards (high personal standards that are accompanied by being overly self-critical), (3) perceived high parental expectations, (3) perceived parental criticism, (4) doubts about action (insecurity about one’s level of performance), and (5) organization (preference for order) [16, 26].

Exercise addiction has recently been reviewed in conjunction with perfectionism [12]. However, the review excluded studies of exercise addiction connected to eating disorders (sometimes termed “secondary exercise addiction”). For example, the study conducted by Bratland-Sanda and colleagues [27] was not included in the review, possibly generating a less complete understanding of how exercise addiction may relate to perfectionism. Moreover, Bircher et al.’s [12] review is limited to adults only, whereas it was suggested that younger individuals may also be at risk for experiencing exercise addiction [28]. Another limitation of the previous review on exercise addiction and perfectionism is that it does not address how dimensions of perfectionism relate to exercise addiction [12]. Therefore, the main aim of the current systematic literature review is to expand the review of Bircher and colleagues’ [12] work by also examining studies that focused on eating disorder–related exercise addiction, exercise addiction in younger individuals, and dimensions of perfectionism.

Methods

The current review uses the guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) [29,30,31]. The selected studies were gathered through searching three databases: PsycINFO, PubMed/Medline, and SPORTDiscus. The potential studies were identified using the following search terms and a Boolean logic: exercise addiction, exercise dependence, compulsive exercise, or obligatory exercise and perfectionism. Additional searches on Google Scholar were conducted to try to ensure that no relevant studies were excluded.

Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria were (1) journal articles in English, (2) published in a peer-reviewed journal, (3) had abstracts containing one or more of the key search terms identified, (4) referred to the link between exercise addiction and perfectionism, and (5) used any form(s) of research design. Dissertations/theses, oral/poster conference presentations, reviews, and books were excluded. Only studies that reported correlations between perfectionism and exercise addiction, or differences in perfectionism among “exercise addicts” and “nonaddicts,” were included. No limitations in age or athletic status were applied in the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Consequently, studies measuring exercise addiction in teenagers, athletes, or clinical samples were included in the review. The exclusion criteria removed studies for which full text was not available. Table 1 summarizes the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data Extraction and Analysis

The selected studies were described using the following classifications: countries/nations where the study took place; characteristics of participants (e.g., athlete versus community-dwelling individual versus clinical patient, number or study participants, gender, grouping strategies, and type of sports reported); instruments used for measuring exercise addiction and perfectionism; and results. Key information from the articles was then grouped based on their characteristics (i.e., general adult populations without clinical diagnoses, teenage populations without clinical diagnoses, athlete populations, and clinical populations). Within each population, the associations between exercise addiction and perfectionism and its constituent domains were considered.

Quality Assessment

The included studies were evaluated with the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) 2018 version. The MMAT has been used in the evaluation of the quality of studies included in systematic reviews or meta-analyses [32,33,34]. In this quality assessment process, each included study is first evaluated using two screening questions about the clarity of research questions and whether the collected data can address the research questions. Then the included studies are evaluated based on their study designs. Each of the questions can be answered with “Yes,” “No,” or “Cannot tell” [33]. This way the MMAT is suitable for assessing the quality of included studies in a reliable manner, taking into account differences in research protocols/designs. Two authors (GC and IDJ) worked together closely in discussing the included studies based on the MMAT protocol.

Results

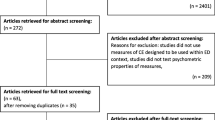

The selection process resulted in 60 potential articles. After further examination, 11 duplicates were excluded. The remaining 49 articles were next examined on the basis of their abstracts. At this stage, 20 articles were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Of the remaining 29 articles, seven were removed because they reported psychometric studies which focused on scale validity rather than on the relationship between exercise addiction and perfectionism. Figure 1 presents the selection process in the review.

Quality Assessment of Included Studies

Of the 22 included studies, none had problems that jeopardized their quality. The studies were guided by clear research questions, and the data collected allowed the researchers to address the questions. From a methodological standpoint, only a few studies were deemed to have concerns about the measurements used. For example, Davis [35] used the general perfectionism scale of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire rather than a specific tool. A study by Levallius and colleagues [36] measured negative perfectionism indirectly by using the Structural Analysis of Social Behavior (SASB). Though indirect measures of perfectionism were not part of the exclusion criteria, no empirical evidence lends support for the use of the SASB as an index of negative perfectionism. The rest of the included studies were deemed to have been conducted in proper manner based on the MMAT. The summary of the quality assessment is presented in Table 2.

Characteristics of Included Studies

Twenty-two studies were included. Studies were conducted between 1990 and 2019 (Table 3). All included studies were conducted in Western countries. Seven studies were conducted in the UK [39, 42,43,44, 46, 48, 51], four in the USA [37, 38, 40, 41], three in Italy [45, 52, 53] and Australia [47, 50, 54], and one in each of the following five nations: Canada [35], Norway [27], Denmark [49], Sweden [36], and Germany [55].

Of the included studies, the sample size varied considerably ranging from 44 [41] to 3255 [36] participants. Three studies had samples of more than 1000 participants [36, 46, 55]. Most studies examined both females and males, with three recruiting only females [27, 35, 44] and two studies examining only males [37, 41].

Regarding participants, thirteen studies sampled general adult populations [35, 37, 39,40,41, 44, 45, 49,50,51,52,53,54], and three assessed teenagers without clinical diagnoses [38, 46, 48]. Three other studies tested amateur athletes [42, 43, 55], and another three assessed clinical samples [27, 36, 47]. Participants’ types of exercise/sport also differed among the studies. Three studies focused on runners [37, 42, 43] and one on bodybuilders [41]; four studies examined participants in mixed sports [49, 50, 52, 54], while the rest did not provide information about the participants’ types of sport/exercise.

Analytical Strategies

In studying the possible associations between exercise addiction and perfectionism or its domains, most studies adopted correlation or regression analyses within a sample (e.g., middle-distance runners, high school students, regular exercisers). Subsequently, they also examined differences in perfectionism between subgroups of the sample, namely, those with exercise addiction or with high scores on exercise addiction measures and those without exercise addiction or with low scores on exercise addiction measures [37, 39, 40, 49, 52]. The studies differed regarding how they divided the participants, with some using median splits and others using cutoff score. Five studies directly compared mean differences of perfectionism scores between participants with and without exercise addiction [36, 37, 39, 40, 49].

Instruments

Exercise Addiction

The included studies used different instruments to assess exercise addiction. These included the Exercise Dependence Scale (EDS) [40, 50,51,52,53], Obligatory Exercise Questionnaire (OEQ) [37,38,39], Exercise Dependence Questionnaire (EDQ) [36, 43, 45], Compulsive Exercise Test (CET) [44, 46, 48], and Exercise Addiction Inventory (EAI) [49]. Two studies used measures not specifically assessing exercise addiction. One used the exercise dependence subscale of the Muscle Dysmorphia Inventory (MDI) [41], while the other [37] used the addiction subscale of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire, which is a general measure of addiction not specific to exercise addiction.

Perfectionism

Perfectionism was measured with several different instruments. Eight studies used the perfectionism subscale from the Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI-P), with three using the original EDI [37,38,39], four using the Eating Disorder Inventory second edition (EDI-2) [27, 40, 46, 49], and one using the Eating Disorder Inventory third edition (EDI-3) [47]. These tools assess unidimensional perfectionism despite some views that they may reflect multidimensional measures [56]. Except for the study conducted by Steffen and Brehm [38], the articles using the EDI-P analyzed their results in a unidimensional rather than multidimensional way.

Six studies assessed perfectionism using the FMPS [37, 41, 42, 44, 52, 53], two used the HF-MPS [43, 50], two used the CAPS [46, 48], and one used Cox’s short version of the HF-MPS (Cox MPS) [51]. One study used a subscale of the FMPS assessing concerns over mistakes and the Clinical Perfectionism Questionnaire (CPQ) as its measures of perfectionism [54]. Another study used the Multidimensional Inventory of Perfectionism in Sport (MIPS) [55]. While 21 studies measured perfectionism using a scale or a subscale of perfectionism directly, one study measured perfectionism indirectly by using the SASB [36].

Links between Exercise Addiction and Perfectionism

General Adult Population

Thirteen included studies examined links between exercise addiction and perfectionism in general adult populations. Davis [35] examined 96 female university students and reported that perfectionism positively correlated with exercise addiction scores. However, the association was moderated by habits of exercising, with the association evident only in a regularly exercising group. Kuennen and Waldron [41] analyzed 44 men (aged 20–59 years) who regularly participated in resistance training. They found that perfectionism, as assessed using the total FMPS score, correlated positively (r = 0.35, p < .05) with exercise addiction scores.

Hagan and Hausenblas [40] also studied the relationship between perfectionism and exercise addiction among university students. They reported that students scoring above the median on the EAS displayed significantly higher perfectionism scores than students who scored below the EAS median. Two other studies reported similar conclusions. A study by Grandi and colleagues [45] in Italy and another by Lichtenstein and colleagues [49] in Denmark showed that participants who scored higher on exercise addiction measures had significantly higher scores of perfectionism than their non-exercise addiction counterparts.

The studies discussed above offer insight into general associations between perfectionism and exercise addiction. Few studies delved deeper into analysis and tested whether associations between exercise addiction and perfectionism may be driven by specific dimensions of perfectionism. Coen and Ogles [37] used the full FMPS among a sample of marathon runners. They compared individuals with high tendencies to overexercise (scoring high on exercise addiction measures) to those with lower tendencies. The two groups differed in the FMPS domains of concern over mistakes, doubt about actions, personal standards, and organization, with the higher-exercise addiction group scoring higher on all domains. Costa and colleagues [52] studied the relationships between maladaptive aspects of perfectionism, as reflected in the domains of concern over mistakes and doubts about action, and exercise addiction. The results revealed that maladaptive perfectionism was positively correlated (r = 0.43, p < .01) with exercise addiction in an Italian sample aged 19–22 years. Another study by Costa and colleagues [53] with 169 Italians aged 18–38 years revealed that the maladaptive aspects of perfectionism were related to exercise addiction symptoms of tolerance, continuance, withdrawal, reduced time for other activities, and diminished control. Egan and colleagues [54] analyzed 368 individuals who regularly exercised. They found that scores on the FMPS domain of concern over mistakes were positively correlated with measures of avoidance/rule-driven behavior, weight control, and mood improvement relating to exercise addiction. Another study focused on the domain of high personal standards in the FMPS. Ninety-seven regularly exercising individuals participated in a study finding positive associations between scores on the perfectionism domain of high personal standard and different domains of exercise addiction [44]. Specifically, high personal standards were associated with avoidance and rule-driven aspects of perfectionism assessed via the CET. These findings suggest that people with high personal standard are more likely to continue exercising despite injury or compensate for missed exercise schedules. However, personal standards were not related to the exercise addiction domains of weight control, enjoyment of exercise, and exercise rigidity.

Two studies used the HF-MPS as a measure of perfectionism. Miller and Mesagno examined 90 individuals who regularly exercised and found that only the SOP and SPP subscales of perfectionism were related to exercise addiction [50]. The conclusion is corroborated by a study conducted by Hill, Robson, and Stamp [46] who examined 248 gym members using Cox’s MPS. However, Hill and colleagues found that the SOP and SPP domains had different pattern of association with exercise addiction. While both SOP and SPP scores positively correlated with those assessing withdrawal symptoms, continuance of exercise, tolerance, diminished control, reduction in other activities, and intention, only the SOP scores correlated positively with time spent exercising. Although the 12 studies listed above provide seemingly consistent results, one study did not observe a relationship between perfectionism and exercise addiction. Matheson and Crawford-Wright [39] reported a negative finding from their study of 274 university students. The researchers found no difference in perfectionism among students with high scores on exercise addiction measures and those with low scores.

Teenagers

Three studies examined relationships between perfectionism and exercise addiction in teenagers. Steffen and colleagues [38] reported a positive association between exercise addiction and perfectionism in 250 US high school students. Furthermore, their analyses showed positive associations between perfectionism and emotional aspects of exercise and exercise preoccupation. Goodwin and colleagues [46] conducted a study with 1488 UK adolescents. Their analyses showed that the association between perfectionism and exercise addiction was moderated by gender. Although self-oriented perfectionism and social-oriented perfectionism were positively associated with exercise addiction in boys, only self-oriented perfectionism was associated with exercise addiction in girls. The same researchers followed up the participants after 2 years [48]. At the end of the follow-up period, the patterns of associations between exercise addiction and perfectionism have changed. At the follow-up assessment, only self-oriented perfectionism was positively associated with exercise addiction in boys, with no associations observed in girls.

Amateur Athletes

Three included studies focused on individuals competing in specific sports. Hauck and colleagues [55] examined the mediation effect of exercise addiction on the relationship between perfectionism and food addiction in German amateur athletes. Their findings revealed that exercise addiction was positively related to both positive and negative aspects of perfectionism. Among 246 UK middle-distance runners, Hall and colleagues [42] found that exercise addiction scores correlated positively with overall perfectionism scores. Furthermore, exercise addiction was positively related to all domains of the FMPS. The researchers replicated the study by using a different measure of perfectionism [43]. In the latter study, the researchers found that exercise addiction scores were positively associated with those on the SOP and SPP domains of the HF-MPS. Moreover, SOP and SPP scores were positively associated with several behavioral and emotional aspects of exercise addiction including withdrawal symptoms, positive reward from exercising, and interference with social and family relationships.

Clinical Samples

In a study comparing 59 female adults with eating disorders to 53 without, Bratland-Sanda and colleagues [27] found that perfectionism scores were moderately associated with exercise addiction scores. However, the association was observed only in the patient group. Two other studies examined teenagers with eating disorders. Formby and colleagues [47] studied 104 Australian teenagers with eating disorders. Their analysis showed that exercise addiction measures correlated positively with perfectionism measures. Levallius and colleagues [36] conducted a longitudinal study with two samples: 3116 adolescent girls and 139 adolescent boys who had been diagnosed with eating disorders. In both samples, researchers observed relationships between perfectionism and exercise addiction. Specifically, negative perfectionism scores were significantly higher for those with greater versus lesser exercise addiction scores.

Discussion

The aim of the current review was to expand upon a previous review of exercise addiction and perfectionism [12] by incorporating research that concentrates on “secondary exercise addiction” and exercise addiction in younger populations. Dimensionality aspects of perfectionism were also considered. Of the 22 included articles, 13 studies studied exercise addiction in adult populations without known clinical diagnoses. This number of studies is nearly double that included in the previous review. Despite differences in how studies assessed perfectionism, most studies (12 of 13) reported findings indicating positive associations between aspects of exercise addiction and perfectionism. Exercise addiction appears moderately associated with general perfectionism as well as with specific domains of perfectionism including concern over mistakes and personal standard on the FMPS or SOP and SPP on the HF-MPS. These findings lend further support to the conclusions of a previous review [12]. Although the association between exercise addiction and perfectionism seems strongly supported, Matheson and Crawford-Wright [39] found no differences in perfectionism between obligatory and nonobligatory exercise groups. These authors, however, recognized a limitation of their work in that the size of the group with higher exercise addiction scores was small compared to that with lower scores, potentially precluding identification of a relationship between exercise addiction and perfectionism.

One advantage of the current review is that it also includes studies of adolescents. Based on three included studies, similar relationships as observed in adults may exist in adolescents. Whether generally or at domain-specific levels, perfectionism appears related to exercise addiction. Such an association, however, has been found to be moderated by gender [38, 46, 48]. Given that only three studies focused on teenage populations, more studies are needed to confirm conclusions.

The inclusion of research with athletes is another important aspect of the current study. Researchers have argued that those who participate in competitive sports may be more likely to become addicted to exercise; however, prior reviews have not considered athletes [57]. Similar to the general population, the three studies of athletes suggest that perfectionism, both positive and negative, are positively associated with exercise addiction. However, this inference is drawn largely from the study of runners. Additional studies of athletes participating in other sports are needed. Similarly, in adults or adolescents with eating disorders, exercise addiction and perfectionism appear positively associated. However, in clinical patients, only negative perfectionism appears associated with exercise addiction [36, 47].

Another contribution of the current systematic review is its evaluation of the relationship between exercise addiction and various domains of perfectionism in multiple populations. The findings suggest that the domains of concern over mistakes and doubt about actions as measured with the FMPS may be particularly relevant to exercise addiction [37, 42, 54]. Another dimension of the FMPS that was found to correlate with aspects of exercise addiction is that of personal standards [37, 42, 44]. Exercise addiction was also related to self-oriented perfectionism and socially prescribed perfectionism conception [43, 46, 48, 50, 51]. However, the relationships between these domains and exercise addiction may be moderated by gender [46, 48].

Other researchers used classifications of adaptive-maladaptive or positive-negative perfectionism. Negative perfectionism was associated with exercise addiction in the two studies included here [36, 47]. However, Hauck and colleagues found that positive perfectionism was also positively correlated with exercise addiction [55]. This finding is in line with growing conception that perfectionism should not be conceived as exclusively negative in nature and that most people show some (either positive or negative) perfectionist tendencies [20].

While the relationship between exercise addiction and perfectionism in the current review seems to be consistent, it should be noted that the results were obtained with a variety of instruments which could yield weaker or stronger relationships. Comparison is also difficult because the 22 studies included here used different terminologies. This heterogeneity is an ongoing concern as noted in previous reviews on exercise addiction [58, 59] and applies both to assessments of exercise addiction and perfectionism.

Exercise addiction in the current review was primarily assessed with the EDS, with other measures of exercise addiction including the OEQ and EAI. It should be noted that while all these instruments quantify severity of exercise addiction, they evaluate different domains. None are diagnostic instruments (as there are no formal criteria for exercise addiction); as such, one may argue that they assess risk for or potential severity of exercise addiction [9]. They may also be viewed as screening tools selected on the basis of convictions and/or beliefs about their reliability in the context of the target measures. Although there are no uniformly accepted criteria for exercise addiction, the construct shares similarities with other behavioral addictions, such as gambling disorder [9]. Subject experts from different professions (e.g., athletes, physicians, coaches, physiotherapists) appear to agree upon main features defining exercise addiction [60]. However, as this review also reveals, assessments on exercise addiction differ between studies. Given the absence of a definitive set of criteria for exercise addiction, an empirically supported consensus statement on how to conceptualize and define exercise addiction is needed. Such a consensus would provide a foundation for the development and testing of prevention and treatment strategies.

The strengths of this review include the use of the PRISMA protocol and the examination of relationships between exercise addiction and perfectionism and its various domains in multiple populations. Further, the current review expands the review of Bircher and colleagues [12] not only by also looking at the dimensions of perfectionism but also by including three times more studies (22 versus 7) than the earlier review. One limitation of this review, stemming from the English language–only delimitation set by the authors, is that the included studies are all from Western nations and, therefore, the associations between exercise addiction and perfectionism may not generalize to non-Western cultures. Another limitation is that the included studies are mainly cross-sectional in nature, and future longitudinal studies are needed.

Conclusion

Exercise addiction appears to be positively associated with perfectionism and its subdomains. The relationship, however, is relatively weak. The shared variance between the two (refer to r2 in values in Table 3) ranges between 3 and 25% and at best may be close to moderate in a few studies. The different instruments used, populations studied, forms of exercise or sport, and several other factors may contribute to differences in the shared variance between exercise addiction and perfectionism. The main message of this review is that a consistent, but relatively weak, positive association exists between exercise addiction and perfectionism and, therefore, perfectionism is a personal factor that may augment one’s proneness to exercise addiction.

References

American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). Benefits and risks associated with physical activity. 10th ed. ACSM’s Guidelines For Exercise Testing and Prescription. Philadelphia: Walter Kluwers; 2018. 3 p.

Szabo A, Griffiths MD, Marcos R de LV, Mervó B, Demetrovics Z. Methodological and conceptual limitations in exercise addiction research. Yale J Biol Med [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2019 Sep 26];88:303–8. Available from: http://real.mtak.hu/28079/1/Szabo_etal_15_YALE.pdf

Berczik K, Szabó A, Griffiths MD, Kurimay T, Kun B, Urbán R, et al. Exercise addiction: symptoms, diagnosis, epidemiology, and etiology. Subst Use Misuse [Internet]. 2012 Feb 13 [cited 2019 Sep 23];47(4):403–17. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2011.639120

Szabo A, De La Vega R, Ruiz-Barquín R, Rivera O. Exercise addiction in Spanish athletes: investigation of the roles of gender, social context and level of involvement. J Behav Addict [Internet]. 2013 Dec 13 [cited 2019 Sep 23];2(4):249–52. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1556/JBA.2.2013.4.9.

Szabo A, Kovacsik R. When passion appears, exercise addiction disappears. Swiss J Psychol [Internet]. 2019 Aug;78(3–4):137–42. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185/a000228

Egorov AY, Szabo A. The exercise paradox: an interactional model for a clearer conceptualization of exercise addiction. J Behav Addict. 2013;2(4):199–208.

Goodman A. Addiction: definition and implications. Addiction [Internet]. 1990 Nov 1 [cited 2020 Feb 12];85(11):1403–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb01620.x

Mónok K, Berczik K, Urbán R, Szabo A, Griffiths MD, Farkas J, et al. Psychometric properties and concurrent validity of two exercise addiction measures: a population wide study. Psychol Sport Exerc [Internet]. 2012 Nov 1 [cited 2019 Sep 23];13(6):739–46. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1469029212000829

Szabo A. Addiction, passion, or confusion? New theoretical insights on exercise addiction research from the case study of a female body builder. Eur J Psychol. 2018;14(2):296–316.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorder fifth edition. 2013.

World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Diseases and related health problems [Internet]. 11th ed. 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 13]. Available from: https://icd.who.int/en

Bircher J, Griffiths MD, Kasos K, Demetrovics Z, Szabo A. Exercise addiction and personality: a two-decade systematic review of the empirical literature (1995-2016). Balt J Sport Heal Sci. 2017;3(106):19–33.

Myers SG, Fisher PL, Wells A. Belief domains of the Obsessive Beliefs Questionnaire-44 (OBQ-44) and their specific relationship with obsessive-compulsive symptoms. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(3):475–84.

Ashby JS, Bruner LP. Multidimensional perfectionism and obsessive-compulsive behaviors. J Coll Couns. 2005;8(1):31–40.

Bieling PJ, Israeli AL, Antony MM. Is perfectionism good, bad, or both? Examining models of the perfectionism construct. Pers Individ Dif. 2004;36(6):1373–85.

Cox BJ, Enns MW, Clara IP. The multidimensional structure of perfectionism in clinically distressed and college student samples. Psychol Assess. 2002;14(3):365–73.

Arnkoff D, Minarik ML. Relations of eating behavior and symptoms of depression and anxiety to the dimensions of perfectionism among undergraduate women. Cognit Ther Res. 1996;20(2):155–69.

Accordino DB, Accordino MP, Slaney RB. An investigation of perfectionism, mental health, achievement, and achievement motivation in adolescents. Psychol Sch. 2000;37(6):535–45.

Moroz M, Dunkley DM. Self-critical perfectionism and depressive symptoms: low self-esteem and experiential avoidance as mediators. Pers Individ Dif [Internet]. 2015;87:174–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.07.044, 2015.

Stoeber J, Stoeber FS. Domains of perfectionism: prevalence and relationships with perfectionism, gender, age, and satisfaction with life. Pers Individ Dif. 2009;46(4):530–5.

Gnilka PB, Ashby JS, Noble CM. Multidimensional perfectionism and anxiety: differences among individuals with perfectionism and tests of a coping-mediation model. J Couns Dev. 2012;90(4):427–36.

Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Turnbull-Donovan W, Mikail SF. The Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale: reliability, validity, and psychometric properties in psychiatric samples.Pdf. Psychol Assessment A J Consult Clin Psychol 1991;3(3):464–468.

Stoeber J. Comparing two short forms of the Hewitt–Flett Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale. Assessment. 2018;25(5):578–88.

Rice SPM, Loscalzo Y, Giannini M, Rice KG. Perfectionism in Italy and the USA: measurement invariance and implications for cross-cultural assessment. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2018.

Flett GL, Hewitt PL, Besser A, Su C, Vaillancourt T, Boucher D, et al. The Child–Adolescent Perfectionism Scale. J Psychoeduc Assess [Internet]. 2016 Oct 3 [cited 2020 Feb 12];34(7):634–52. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282916651381

Frost RO, Marten P, Lahart C, Rosenblate R. The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognit Ther Res. 1990 Oct;14(5):449–68.

Bratland-Sanda S, Martinsen EW, Rosenvinge JH, Rã Ã, Hoffart A, Sundgot-Borgen J. Exercise dependence score in patients with longstanding eating disorders and controls: the importance of affect regulation and physical activity intensity. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2011;19(3):249–55.

Lichtenstein MB, Griffiths MD, Hemmingsen SD, Støving RK. Exercise addiction in adolescents and emerging adults - validation of a youth version of the Exercise Addiction Inventory. J Behav Addict [Internet]. 2018 Mar 1 [cited 2020 Jul 28];7(1):117–25. Available from: https://akjournals.com/view/journals/2006/7/1/article-p117.xml

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–34.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement (reprinted from Annals of Internal Medicine). Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg [Internet]. 2010;8(5):336–41 Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1743919110000403.

Queiroga Souto R, Khanassov V, Nha Hong Q, Bush PL, Vedel I, Pluye P. Systematic mixed studies reviews: updating results on the reliability and efficiency of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. Int J Nurs Stud [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2020 Feb 17];52:500–1. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.08.010

Hong QN, Pluye P, Sergi F, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT ), version 2018. McGill Dep Fam Med [Internet] 2018;1–11. Available from: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf

Stretton T, Cochrane T, Narayan V. Exploring mobile mixed reality in healthcare higher education: a systematic review. Res Learn Technol [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2020 Feb 17];26. Available from: https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v26.2131

Davis C. Weight and diet preoccupation and addictiveness: the role of exercise. Pers Individ Dif. 1990;11(8):823–7.

Levallius J, Collin C, Birgegård A. Now you see it, now you don’t: compulsive exercise in adolescents with an eating disorder. J Eat Disord. 2017;5(1):1–9.

Coen SP, Ogles BM. Psychological characteristics of the obligatory runner: a critical examination of the anorexia analogue hypothesis. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1993;15(3):338–54.

Steffen JJ, Brehm BJ. The dimensions of obligatory exercise. Eat Disord. 1999;7:219–26.

Matheson H, Crawford-Wright A. An examination of eating disorder profiles in student obligatory and non-obligatory exercisers. J Sport Behav. 2000;23(1):42.

Hagan AL, Hausenblas HA. The relationship between exercise dependence symptoms and perfectionism. Amerian J Heal Stud. 2003;18(2/3):133–7.

Kuennen M, Waldron J. Relationships between specific personality traits, fat free mass indices, and the Muscle Dysmorphia Inventory. J Sport Behav. 2007;30(4):453.

Hall HK, Kerr AW, Kozub SA, Finnie SB. Motivational antecedents of obligatory exercise: the influence of achievement goals and multidimensional perfectionism. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2007;8(3):297–316.

Hall HK, Hill AP, Appleton PR, Kozub SA. The mediating influence of unconditional self-acceptance and labile self-esteem on the relationship between multidimensional perfectionism and exercise dependence. Psychol sport Exerc [Internet]. 2009;10(1):35–44. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2008.05.003, 2009.

Taranis L, Meyer C. Perfectionism and compulsive exercise among female exercisers: high personal standards or self-criticism? Pers Individ Dif [Internet]. 2010;49(1):3–7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.02.024, 2010.

Grandi S, Clementi C, Guidi J, Benassi M, Tossani E. Personality characteristics and psychological distress associated with primary exercise dependence: an exploratory study. Psychiatry res [Internet]. 2011;189(2):270–5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.02.025, 2011.

Goodwin H, Haycraft E, Taranis L, Meyer C. Psychometric evaluation of the Compulsive Exercise Test (CET) in an adolescent population: links with eating psychopathology. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2011;19(3):269–79.

Formby P, Watson HJ, Hilyard A, Martin K, Egan SJ. Psychometric properties of the Compulsive Exercise Test in an adolescent eating disorder population. Eat Behav [Internet]. 2014;15(4):555–7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.08.013, 2014.

Goodwin H, Haycraft E, Meyer C. Psychological risk factors for compulsive exercise: a longitudinal investigation of adolescent boys and girls. Pers Individ Dif [Internet]. 2014;68:83–6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.03.048, 2014.

Lichtenstein MB, Christiansen E, Elklit A, Bilenberg N, Støving RK. Exercise addiction: a study of eating disorder symptoms, quality of life, personality traits and attachment styles. Psychiatry res [Internet]. 2014;215(2):410–6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.11.010, 2014.

Miller KJ, Mesagno C. Personality traits and exercise dependence: exploring the role of narcissism and perfectionism. Int J sport Exerc Psychol [Internet]. 2014;12(4):368–81. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2014.932821, 2014.

Hill AP, Robson SJ, Stamp GM. The predictive ability of perfectionistic traits and self-presentational styles in relation to exercise dependence. Pers Individ Dif [Internet]. 2015;86:176–83. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.06.015, 2015.

Costa S, Coppolino P, Oliva P. Exercise dependence and maladaptive perfectionism: the mediating role of basic psychological needs. Int J Ment health addict [Internet]. 2016;14(3):241–56. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-015-9586-6, 2016.

Costa S, Hausenblas HA, Oliva P, Cuzzocrea F, Larcan R. Maladaptive perfectionism as mediator among psychological control, eating disorders, and exercise dependence symptoms in habitual exerciser. J Behav Addict. 2016;5(1):77–89.

Egan SJ, Bodill K, Watson HJ, Valentine E, Shu C, Hagger MS. Compulsive exercise as a mediator between clinical perfectionism and eating pathology. Eat Behav. 2017;24:11–6.

Hauck C, Schipfer M, Ellrott T, Cook B. “Always do your best!”—The relationship between food addiction, exercise dependence, and perfectionism in amateur athletes. Ger J Exerc Sport Res. 2019.

Sherry SB, Hewitt PL, Besser A, McGee BJ, Flett GL. Self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism in the Eating Disorder Inventory Perfectionism subscale. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;35(1):69–79.

Lichtenstein MB, Hinze CJ, Emborg B, Thomsen F, Daugaard Hemmingsen S. Compulsive exercise: links, risks and challenges faced. 2017 [cited 2020 May 13]; Available from: https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S113093, Volume 10, 85, 95.

Baptista JG, Filho PNC, Poretti M, Espírito-Santo G Do, Assis M, Palma A. Exercise dependence: an updated systematic review. J Exerc Physiol Online 2019;22(5):105–125.

Hausenblas HA, Downs DS. Exercise dependence: a systematic review. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2002;3(2):89–123.

MacFarlane L, Owens G, Del Pozo Cruz B. Identifying the features of an exercise addiction: a Delphi study. J Behav Addict. 2016;5(3):474–84.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Eötvös Loránd University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest with respect to the content of this manuscript. Dr. Potenza has consulted for and advised Game Day Data, the Addiction Policy Forum, AXA, Idorsia, and Opiant/Lakelight Therapeutics; received research support from the Mohegan Sun Casino, Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling, and the National Center for Responsible Gaming (now the International Center for Responsible Gaming); participated in surveys, mailings, or telephone consultations related to drug addiction, impulse control disorders, or other health topics; consulted for law offices, the federal public defender’s office, and gambling entities on issues related to impulse control and addictive disorders; provided clinical care in the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services Problem Gambling Services Program; performed grant reviews for multiple agencies; edited journals and journal sections; given academic lectures in grand rounds, CME events, and other clinical/scientific venues; and generated books or chapters for publishers of mental health texts. The other authors report no disclosures. The views presented in this manuscript represent those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funding agencies.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Hot Topics

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Çakın, G., Juwono, I.D., Potenza, M.N. et al. Exercise Addiction and Perfectionism: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Curr Addict Rep 8, 144–155 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-021-00358-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-021-00358-8