Abstract

Background

Salmonella are frequently isolated from chickens and their products. Prevalent serogroups and serovars of Salmonella as well as their genotypes and antibiograms were determined for cloacal samples from 1595 chickens. To understand the possible serovar and H antigens for transmission between chicken and human, serovars and their H antigens of 164 chicken and 5314 human isolates were compared.

Results

Prevalence of Salmonella differed among chicken lines and ages. Chicken and human isolates belonged mainly to serogroup B, C1, C2-C3, D, and E. 13 serovars and 66 serovars were identified for chicken and human isolates respectively. The common serovars for chicken and human isolates were S. Typhimurium, S. Enteritidis, S. Albany, S. Derby, and S. Anatum and shared common H1 antigens "g complex; i; e,h; and z4,z24" and H2 antigens "1 complex and -". In human isolates, H1 antigen "i" and H2 antigen "-" were common in all serogroups. In chicken, antimicrobial susceptibility differed among serogroups, serovars and three counties. All isolates were susceptible to cefazolin and ceftriaxone, but highly resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, flumequine, streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and tetracycline. Except those isolates of serogroup C1 of Chick group and serogroup G, all isolates were multi-drug resistance. Only S. Kubacha, S. Typhimurium, S. Grampian, and S. Mons were resistant to ciprofloxacin and/or enrofloxacin.

Conclusion

In chicken, prevalent serogroups and serovars were associated with chicken ages, lines and regions; and flouroquinolone-resistant and MDR isolates emerged. H1 antigens "g complex and i" and H2 antigens "1 complex and -" might be important for transmission of Salmonella between chicken and human.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium, as two main zoonotic and broad-host-range pathogens that cause human salmonellosis, have been frequently isolated from poultry and their products [1–8]. Prevalence of Salmonella differs between layers and broilers [9, 10]. Factors influencing the prevalence of chicken-associated Salmonella are feeds and growth environment [11], transportation process [12, 13], and chick sources [14]. Moreover, age-associated prevalence has been reported in layers, maximal prevalence at 18 weeks before egg production and gradually decreases with aging [15]. In broiler the prevalence differed depending on sale sites from 17.9% in slaughterhouses [16] and up to nearly 100% in the open markets and supermarkets [17].

Appearance of monophasic variants such as in S. Typhimurium [4,5,12:1:-] [18, 19] increases the problem in serotyping. Therefore, molecular methods have been developed to differentiate the serovars based on the nucleotide sequence variations in flagellar structural genes fliC and fljB[20–22] and PFGE analysis [15, 23, 24]. Prevalent serovars differ between chickens and ducks [25] and are associated with chicken lines and geographic area [15, 25–27]. In Taiwan, we reported that Salmonella serogroup C1 and B, especially S. Typhimurium, were predominant Salmonella in duck and geese [7, 8]. In another study of duck, the prevalence of Salmonella was 4.6% and S. Potsdam, S. Dusseldorf, and S. Indiana were the predominant serovars [28]. Therefore, we analyzed the prevalence of Salmonellae among different chicken sources and determined serotypes by PFGE analysis first, followed by traditional agglutination test of each genotype. After characterizing antibiograms and genomic variations in chromosome and plasmid of chicken isolates, flagellar antigens of chicken and human isolates were compared to understand the common antigens possibly for transmission of Salmonella between human and chicken.

Methods

Sample collection and enrichment

Totally 1595 chickens of 1-year-old broiler breeder, 1-day-old chicks (Chick) and 9-week-old chickens (NHC) of Taiwan broiler chicken, 1-year-old layers and 3-week-old broiler were sampled by 108C Amies Agar Gel - Single plastic swab (Copan Diagnostic Inc. Murrieta CA 92562 USA) from cloaca of each chicken fed at different farms in Chiayi of Taiwan from 2002 to 2003. Layers and broilers were fed in commercial cage and house farm respectively. The sampled swabs were grown in 9 mL of gram-negative broth (GN, Difco 0486) at 37°C for 24 h. Over-night GN bacterial broth was streaked on xylose lysine deoxycholate (XLD, Difco 0788) plates, which were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Black colonies were further examined by biochemical tests including triple sugar iron agar (TSI), Christensen's urea agar (URE), Simmons' citrate agar (CIT), sulfide-indole-motility medium (SIM), Voges-Proskauer medium (VP), Moller's ornithine decarboxylase medium (ORN), lysine iron agar (LIA) and mobility-indole-ornithine agar (MIO) purchased from Merck (Taiwan). At least two positive isolates from each plate were maintained on brain heart infusion agar (BHIA). In addition, Salmonellae from 9-week-old NHC in Tainan (36 isolates) and Pintung (30 isolates) at same period were also analyzed.

Serogroup and serotype identification

Salmonella-positive isolates were further serogrouped by the slide agglutination test with the use of O-antigen antiserum and serotyped by the tube agglutination test with the use of H-antigen antisera. Both antisera were purchased from Difco (Becton Dickinson Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). In addition, 5314 Salmonellae were collected from 19 medical centers and district hospitals located throughout the countries from 2003 to 2005 and serotyped in the Salmonella Reference Laboratory of Centers for Disease Control (CDC), Department of Health, Taiwan, with antisera purchased from S&A Reagents Lab (Bangkok, Thailand), Denka Seiken (Tokyo, Japan), Statens Serum Institut (Copenhagen, Denmark), and a local biotech company, LTK Biolaboratories (Taoyuan, Taiwan). Phase induction was performed using a paper-bridged method developed in the laboratory of Taiwan CDC [29].

Antimicrobial susceptibility test

Each isolate was examined by disk diffusion method for its susceptibility to the antimicrobial agents including ampicillin (A, 10 μg), cefazolin (CZ, 30 μg), ceftriaxone (Cro, 30 μg), chloramphenicol (C. 30 μg), streptomycin (S, 10 μg), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprium (Sxt, 1.25/23.75 μg), and tetracycline (T, 30 μg). In addition, resistance to three fluoroquinolones: flumequine (Ub, 30 μg) of limited spectrum quinolone and enrofloxacin (En, 5 μg) as well as ciprofloxacin (Ci, 5 μg) of broad spectrum quinolone. While single bacterial colony was taken into 5 ml of Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB; Merck, Taiwan) and cultured at 37°C for 8 hrs, bacterial broth was then adjusted to 0.5 Mcfarland and plated on Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA; Merck, Taiwan). Antimicrobial disks (BD Diagnostic systems, USA) were plated onto MHA agar and then incubated at 37°C for 18 hrs. Susceptibility and resistance were determined according to the interpretation criteria to E. coli (ATCC No. 25922) established by Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) standard [30]. Multi-drug resistance (MDR) isolate is defined as that isolate resistance to two or more antibiotics belonging to different antibiotic classes.

Plasmid and genotype analysis

Plasmid DNA pattern was determined by Kado and Liu method [31] and purified plasmid DNA was subjected to gel electrophoresis with 0.6% SeaKem GTG agarose (Cambrex Bio Science Rockland, Inc, Rockland, ME, USA) at 50 V for 2.5 hrs. Genotypes of all isolates were determined by PFGE analysis with restriction endonuclease Xba I digestion. The procedure of PFGE analysis was described earlier [32]. The digested DNA was separated by CHEF Mapper XA system (BioRad, Hercules, California, USA) in 0.5 × TBE at 14°C for 22 h with Auto-Algorithm model of 30-600 kb, 6 V/cm, switching interval 4.0-70.0 sec. The genotypes were defined as 3 band differences between two isolates [33].

Results

Prevalent serogroups and serovars among chicken lines and locations

Prevalence of Salmonella differed between chicken lines (0% for layer vs 0.3% for breeder broiler and 11.3% for broiler) and ages from 10.3% for Chick and 3.8% for NHC of Taiwan broiler chicken (Table 1). 164 Salmonella isolates belonged to serogroup C1, B, D, C2-C3, E, and G in the decreasing order and the number of serogroups differed among 3 counties. Further, region-specific serogroups were identified as serogroup G in Chiayi, serogroup D in Tainan, and serogroup C2-C3 and E in Pintung (Table 1). In Chiayi, age-associated serogroups were found for serogroup C1 Salmonella in Chick group and serogroup B and G in NHC group (Table 1).

164 Salmonella isolates were firstly examined for their genotypes by Xba I-PFGE analysis (Figure 1) and further isolates of each genotype were serotyped by traditional agglutination method. In total, 18 PFGE patterns belonged to 13 serovars (Table 2). Except S. Albany and S. Havana that consisted of multiple genotypes, PFGE genotypes matched exactly with serotypes. 13 serovars were S. Derby, S. Kubacha, S. Mons, and S. Typhimurium (containing S. Typhimurium var. Copenhagen) of serogroup B, S. Choleraesuis (containing non-typable serovar), S. Grampian, S. Hissar, and S. Redba of serogroup C1, S. Albany and S. Blockley of serogroup C2-C3, S. Enteritidis of serogroup D, S. Anatum of serogroup E and S. Havana of serogroup G (Table 2). Predominant serovar in each serogroup was S. Mons, not S. Typhimurium, in serogroup B, S. Choleraesuis from Chick and S. Grampian from NHC in serogroup C1, and S. Albany in serogroup C2-C3 (Table 2).

XbaI-digested PFGE genotypes of each Salmonella serogroups. M: lamda ladder size marker. SC1: non-typable serogroup C1 Salmonella. SC16: S. Redba. C34: S. Derby. SW1: S.Grampian. P15: S. Blockley. P18, P24, and P34: S. Albany. P23: S. Mons. C31: S. Typhimurium var. Copenhagen. SR2: S. Kubacha. P1: S. Derby. P10: S. Typhimurium. C11: S. Enteritidis. P22: S. Anatum. SC9 and SC10: S. Havana. Genotypes I to IV are defined as difference more than 3 bands between two isolates [33].

Antimicrobial susceptibility

All isolates were susceptible to CZ and Cro. In contrast to resistance only to streptomycin for 77 S. Choleraesuis isolates in Chick group and two isolates of serogroup G, all isolates were MDR (Table 3). Serogroup B, C2-C3 and E were highly resistance to A, C, S, Sxt, T and Ub. However, serogroup D was relatively low in resistance to above antimicrobials. Serogroup and serovars isolated from broiler and NHC group differed in resistance to three quinolone antimicrobials. Except serogroups E and G, all serogroups, were nearly 100% resistance to Ub and only serogroups B and C1 were resistant to En and Ci (Table 3). Among 164 isolates, we only found 4 En-resistant S. Mons and 13 En and Ci-resistant isolates including 2 S. Kubacha isolates, 2 S. Typhimurium isolates, and 1 S. Typhimurium var. Copenhagen isolates of serogroup B and 8 S. Grampian isolates of serogroup C1 (Table 2). Importantly, near 40% of isolates from Pintaung were resistant to En and Ci. According to resistance to 9 antimicrobials tested, 13 antibiograms differed among serogroups and serovars (Table 2 and 3). Highest drug-resistant types L with antibiogram ACCiEnSxtTUb and M with antibiogram ACCiEnSSxtTUb were only found in serogroup B and C1 of NHC group from Pintung mostly and Tainan. Salmonella genomic island (SGI) related ACSSuT resistance was found in serogroup B, C2 and E. Resistance to antimicrobials tested varied among 3 counties (Table 3 and Additional file 1: Table S1). Highest resistance was found in isolates from Pintung, followed by Tainan, and Chiayi and lowest Sxt resistance rate was observed in isolates from Tainan.

Plasmid profile analysis

Based on plasmid number and size determined by gel electrophoresis and plasmid size marker 50 kb and 90 kb of OU7526, in total 19 plasmid profiles were identified and the plasmid profiles and their number differed among serogroups and serovars (Additional file 2: Table S2; Additional file 3: Figure S1). Among 13 serovars, S. Albany, S. Blockley, S. Havana, and S. Redba as well as few isolates of S. Choleraesuis, S. Enteritidis, and S. Typhimurium lacked plasmid. All other serovars harbored at least one plasmid and differed in plasmid profile.

Serovar association between chicken and human isolates

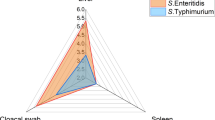

S. Albany, S. Anatum, S. Choleraesuis, S. Derby, S. Enteritidis, and S. Typhimurium were in common for 13 chicken serovars and 66 human serovars and other 7 serovars of chicken isolates were not or barely observed in human (Table 2, 4 and 5). Total serovar number of each serogroup decreased from serogroup C1, B, C2, E to D for human isolates (Table 4). Despite of the presence of 66 serovars, there were only presence of 11 H1 antigens including b, c, d, j, k, r, y, eh, g-complex, and z-complex and 5 H2 antigens including -, z6, lw, 1-complex, and en-complex (Table 4). Common antigens in all serogroups were "i" for H1 antigen: and "-" for H2 antigen. In compared the chicken and human isolates from Taiwan, United Kingdom and United States, the common serovars were S. Typhimurium, S. Enteritidis, S. Anatum, and S. Derby with common antigens of . "g complex; i; z4,z24; and e,h" for H1 antigen and "- and 1 complex" for H2 antigen (Table 5).

Discussion

As one of main pathogen to cause foodborne diseases, Salmonella has been frequently reported among different animal sources, especially more divergent Salmonella serovars found in chickens [34]. With the limited serovars in 164 chicken isolates, serogroups C2, D, E and G were restricted in one county and serogroup B and C1 were found in all three counties (Table 2), suggesting possibly that serogroup B and C1 isolates may be more adapted to chicken. In human isolates, we found that the serovar number in each serogroup were not associated positively with the serogroup prevalence, such as highest serovar number in low prevalent serogroup C1 vs lower serovar number in high prevalent serogroup B and serogroup D (Table 4). These results imply that serogroup C1 may occasionally infect human isolates. Further, serovars are determined by flagellins: H1 and H2 antigens encoded by fliC and fljB. As one of the most important immunogens, flagellin interacts with the toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5) to activate NFκB pathway and proinflammatory genes to regulate innate and adaptive immune system [35–38]. However, aflagellar serovars S. Pullorum and S. Gallinarum cause more severe infection than flagellar serovars in chicken because of aflagellar S. Typhimurium could avoid the TLR5 regulation of IL-1β expression and polymorphonuclear cell infiltration in gut [39]. Such evasion of TLR5 is critical for survival of flagellar bacteria at muscos [40]. [In the present study, we found that i of H1 antigen and lack of H2 antigen were the common antigens for all serogroups in human isolates (Table 4). However, in comparing 13 chicken serovars and 66 human serovars of this study with serovars of chicken and human isolates from UK and USA, only S. Enteritidis, S. Typhimurium, S. Albany, S. Derby, S. Anatum and S. Havana were common in both hosts (Table 5). However, these serovars shares same antigens: g complex; i; and z4,z24 of H1 antigen and 1 complex and - of H2 antigens (Table 5), implying these antigens may be important for Salmonella transmission between chicken and human.

Prevalent serogroups and serovars are related to chicken lines (Table 1)[9, 10] and ages [15]. In layer, age-related prevalence was reported earlier [15] and no Salmonella was isolated from 1-year-old layers in the present study (Table 1). Such age-associated clearance may be due to stronger antigen-specific T-cell response in older chicken [41] and not related to B-cell response [42]. Age-related serovars were also identified in Taiwan broiler chickens (Table 2). Almost all isolates were S. Choleraesuis and non-typable Salmonella (possibly monophasic S. Choleraesuis) of serogroup C1 in Chick group and S. Mons of serogroup B in NHC group (Table 2). As swine-adapted pathogen, S. Cholearesuis has seldom reported from chicken. However, S. Choleraesuis in 1-day-old chicks may be contaminated from the hatchery, particular from eggshell membrane; in which S. Typhimurium, not S. Choleraesuis, is main serovar [43]. If highly invasive S. Choleraesuis could infect chicks and use the chicken as reservoir, it will lead to a public problem of circulating such high invasive serovar in animals. In broiler, prevalence of Salmonella differed between chicken parts (2.36% for legs and 4.25% for breasts of broiler) [19]. Further, prevalent serovars differ between sampling sources e.g. the S. Anatum and S. Rissen in chicken meat [44] and S. Blockley, S. Hadar and S. Bredeney in the cecal samples (24).

Several methods have been developed to differentiate clinical isolates. In this study, PFGE patterns almost matched serotypes, although S. Albany and S. Havana appeared multiple genotypes with highly similar banding patterns (Table 2). Therefore, PFGE typing is a useful tool to assist serotyping of Salmonella isolates before doing traditional serotypes [2, 27]. In contrast to PFGE type, plasmid analysis is the most convenient method for subtyping [15, 45]. In this study, plasmid variations were more diverse than genomic variations; however, S. Albany and S. Havana with highly genomic variations lacked plasmid (Table 2). These results may imply that recent evolution of Salmonella might be mainly through plasmid acquisition to introduce beneficial genes for host serovar to survival.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of Salmonella can be used to monitor drug abuse in different regions (Table 2) [46] and animal sources [44, 47]. Early study reported that Salmonella from chicken, not from human, pig and cattle, was less resistance to A, C, and Sxt [47]. Nevertheless, resistance to T was frequently found in chicken isolates [48]. Since discovery of ACSSuT-resistant region in SGI of S. Typhimurium DT104 [49], variations within SGI and complex integron In104 change the antimicrobial resistance [50]. In this study, our chicken isolates were highly resistant to antimicrobials A, C, S, Sxt, T and Ub (Table 3). These results imply that S. Albany, S. Anatum, S. Grmpian, S. Hissar, S. Kubacha, S. Mons, and S. Typhimurium with resistance types from H to M may be derived from misuse of antimicrobials or due to presence of SGI and/or integron [51]. Mechanism to develop En and Ci resistance is due to mutation in quinolone-resistance determining region or expression of efflux pump [52]. Earlier, fluoroquinolone-resistant Salmonella was seldom reported in poultry's isolates worldwide [10, 44, 47, 48]. Until recently, resistance to similar fluoroquinolones: En and Ci has been reported from chicken in Spain [16]. In contrast to same prevalence of resistance to En and Ci in swine and human isolates [32], we found that resistance rate to En was higher than that of Ci (Table 2). However, En and Ci resistant isolates were only found in few serovars of serogroups B and C1 and mainly in Pintung area (Table 3). These results indicate that possibly En was misuse in Pintung county to induce resistance in prevalent serovars.

Conclusion

13 chicken serovars were identified and differed in drug resistance and prevalence associated with chicken lines, ages and regions. Five serovars were common between these chicken serovars and 66 human serovars

Authors' information

L-HC and C-YL are officials of Animal Disease Control Center ChiaYi County, Taiwan; C-HC is professor of Department of Pediatrics, Chang Gung Children's Hospital and Chang Gung University College of Medicine, Taoyuan, Taiwan; Y-MH and C-PW are professors of Department of Animal Science, National Chiayi University, Chiayi, Taiwan; C-MY was master graduate student of Department of Animal Science, National Chiayi University, Chiayi, Taiwan; C-SC is Chief Investigator of The Central Region Laboratory, Center of Research and Diagnostics, Centers for Disease Control, Taichung, Taiwan; C-YY is professor of Department of Veterinary Medicine, National Chiayi University, Chiayi, Taiwan; C-CC is associate professor of Graduate Institute of Veterinary Public Health, School of Veterinary Medicine, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan; CC is the chairman of Department of Microbiology and Immunology, National Chiayi University, Chiayi, Taiwan.

Abbreviations

- A:

-

ampicillin

- BHIA:

-

brain heart infusion agar

- C:

-

chloramphenicol

- CDC:

-

Center for Disease Control

- Ci:

-

ciprofloxacin

- CIT:

-

Simmons' citrate agar

- Cro:

-

ceftriaxone

- CZ:

-

cefazolin

- En:

-

enrofloxacin

- GN:

-

gram-negative broth

- LIA:

-

lysine iron agar

- MDR:

-

multi-drug resistance

- MHA:

-

Mueller-Hinton agar

- MHB:

-

Mueller-Hinton broth

- MIO:

-

mobility-indole-ornithine agar

- NHC:

-

native hybrid chicken

- ORN:

-

Moller's ornithine decarboxylase medium

- PFGE:

-

pulsed-field gel electrophoresis

- S:

-

streptomycin

- SIM:

-

sulfide-indole-kmotility medium

- Sxt:

-

sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprium

- T:

-

tetracycline

- TSI:

-

triple sugar iron agar

- Ub:

-

flumequine

- URE:

-

Christensen's urea agar

- VP:

-

Voges-Proskauer medium

- XLD:

-

xylose lysine deoxycholate agar.

References

al-Nakhli HM, al-Ogaily ZH, Nassar TJ: Representative Salmonella serovars isolated from poultry and poultry environments in Saudi Arabia. Rev Sci Tech. 1999, 18: 700-709.

Berghold C, Kornschober C, Lederer L, Allerberger F: Occurrence of Salmonella Enteritidis phage type 29 in Austria: an opportunity to assess the relevance of chicken meat as source of human Salmonella infections. EuroSurveill. 2004, 9: 31-34.

Boonmar S, Bangtrakulnonth A, Pornrunangwong S, Marnrim N, Kaneko K, Ogawa M: Salmonella in broiler chickens in Thailand with special reference to contamination of retail meat with Salmonella enteritidis. J Vet Med Sci. 1998, 60: 1233-1236. 10.1292/jvms.60.1233.

Gast RK, Guraya R, Guard-Bouldin J, Holt PS, Moore RW: Colonization of specific regions of the reproductive tract and deposition at different locations inside eggs laid by hens infected with Salmonella enteritidis or Salmonella heidelberg. Avian Dis. 2007, 51: 40-44. 10.1637/0005-2086(2007)051[0040:COSROT]2.0.CO;2.

Gast RK, Guraya R, Guard-Bouldin J, Holt PS: In vitro penetration of egg yolks by Salmonella Enteritidis and Salmonella Heidelberg strains during thirty-six-hour ambient temperature storage. Poult Sci. 2007, 86: 1431-1435.

Phan TT, Khai LT, Ogasawara N, Tam NT, Okatani AT, Akiba M, Hayashidani H: Contamination of Salmonella in retail meats and shrimps in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. J Food Prot. 2005, 68: 1077-1080.

Yu CY, Chou SJ, Yeh CM, Chao MR, Huang KC, Chang YF, Chiou CS, Weill FX, Chiu CH, Chu CH, Chu C: Prevalence and characterization of multidrug-resistant (type ACSSuT) Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strains in isolates from four gosling farms and a hatchery farm. J Clin Microbiol. 2008, 46: 522-526. 10.1128/JCM.00709-07.

Yu CY, Chu C, Chou SJ, Chao MR, Yeh CM, Lo DY, Su YC, Horng YM, Weng BC, Tsay JG, Huang KC: Comparison of the association of age with the infection of Salmonella and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in Pekin ducks and Roman geese. Poult Sci. 2008, 87: 1544-1549. 10.3382/ps.2008-00018.

Limawongpranee S, Hayashidani H, Okatani AT, Ono K, Hirota C, Kaneko K, Ogawa M: Prevalence and persistence of Salmonella in broiler chicken flocks. J Vet Med Sci. 1999, 61: 255-259. 10.1292/jvms.61.255.

Snow LC, Davies RH, Christiansen KH, Carrique-Mas JJ, Wales AD, O'Connor JL, Cook AJ, Evans SJ: Survey of the prevalence of Salmonella species on commercial laying farms in the United Kingdom. Vet Rec. 2007, 161: 471-476.

Hacking WC, Mitchell WR, Carlson HC: Sources of Salmonellae in broiler chickens in Ontario. Can J Comp Med. 1978, 42: 392-399.

Rigby CE, Pettit JR, Baker MF, Bentley AH, Salomons MO, Lior H: Sources of Salmonellae in an uninfected commercially-processed broiler flock. Can J Comp Med. 1980, 44: 267-274.

Rigby CE, Pettit JR, Baker MF, Bentley AH, Salomons MO, Lior H: Flock infection and transport as sources of Salmonellae in broiler chickens and carcasses. Can J Comp Med. 1980, 44: 328-337.

Wales A, Breslin M, Carter B, Sayers R, Davies R: A longitudinal study of environmental Salmonella contamination in caged and free-range layer flocks. Avian Pathol. 2007, 36: 187-197. 10.1080/03079450701338755.

Li X, Payne JB, Santos FB, Levine JF, Anderson KE, Sheldon BW: Salmonella populations and prevalence in layer feces from commercial high-rise houses and characterization of the Salmonella isolates by serotyping, antibiotic resistance analysis, and pulsed field gel electrophoresis. Poult Sci. 2007, 86: 591-597.

Capita R, Alonso-Calleja C, Prieto M: Prevalence of Salmonella enterica serovars and genovars from chicken carcasses in slaughterhouses in Spain. J Appl Microbiol. 2007, 103: 1366-1375. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03368.x.

Vaeteewootacharn K, Sutra S, Vaeteewootacharn S, Sithigon D, Jamjane O, Chomvarin C, Hahnvajanawong C, Thongskulpanich N, Thaewnongiew K: Salmonellosis and the food chain in Khon Kaen, northeastern Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2005, 36: 123-129.

Chiu CH, Su LH, Chu CH, Wang MH, Yeh CM, Weill FX, Chu C: Detection of Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Phage Types DT102, DT104, and U302 by Multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2006, 44: 2354-2358. 10.1128/JCM.00171-06.

De La Torre E, Zapata D, Tello M, Mejía W, Frías N, García-Peña FJ, Mateu EM, Torre E: Several Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype 4,5,12:i: phage types isolated from swine samples originate from serotype Typhimurium DT U302. J Clin Microbiol. 2003, 41: 2395-2400. 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2395-2400.2003.

McQuiston JR, Parrenas R, Ortiz-Rivera M, Gheesling L, Brenner F, Fields PI: Sequencing and comparative analysis of flagellin genes fliC, fljB, and flpA from Salmonella. J Clin Microbiol. 2004, 42: 1923-1932. 10.1128/JCM.42.5.1923-1932.2004.

Mortimer CK, Peters TM, Gharbia SE, Logan JM, Arnold C: Towards the development of a DNA-sequence based approach to serotyping of Salmonella enterica. BMC Microbiol. 2004, 4: 31-10.1186/1471-2180-4-31.

Yoshida C, Franklin K, Konczy P, McQuiston JR, Fields PI, Nash JH, Taboada EN, Rahn K: Methodologies towards the development of an oligonucleotide microarray for determination of Salmonella serotypes. J Microbiol Methods. 2007, 70: 261-271. 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.04.018.

Cardinale E, Gros-Claude JDP Rivoal K, Rose V, Tall F, Mead GC, Salvat G: Epidemiological analysis of Salmonella enterica ssp. enterica serovars Hadar, Brancaster and Enteritidis from humans and broiler chickens in Senegal using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and antibiotic susceptibility. J Appl Microbiol. 2005, 99: 968-977. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02618.x.

Gaul SB, Wedel S, Erdman MM, Harris DJ, Harris IT, Ferris KE, Hoffman I: Use of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of conserved Xba I fragments for identification of swine Salmonella serotypes. J Clin Microbiol. 2007, 45: 472-476. 10.1128/JCM.00962-06.

Murase T, Senjyu K, Maeda T, Tanaka M, Sakae H, Matsumoto Y, Kaneda Y, Ito T, Otsuki K: Monitoring of chicken houses and an attached egg-processing facility in a laying farm for Salmonella contamination between 1994 and 1998. J Food Prot. 2001, 64: 1912-1916.

Pieskus J, Milius J, Michalskiene I, Zagrebneviene G: The distribution of Salmonella serovars in chicken and humans in Lithuania. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med. 2006, 53: 12-16.

van Duijkeren E, Wannet WJB, Houwers DJ, van Pelt W: Serotype and phage type distribution of Salmonella strains isolated from humans, cattle, pigs, and chickens in the Netherlands from 1984 to 2001. J Clin Microbio. 2002, 40: 3980-3985. 10.1128/JCM.40.11.3980-3985.2002.

Tsai HJ, Hsiang PH: The prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibilities of Salmonella and Campylobacter in duck in Taiwan. J Vet Med Sci. 2005, 67: 7-13. 10.1292/jvms.67.7.

Chiou CS, Huang JF, Tsai LH, Hsu KM, Liao CS, Chang HL: A simple and low-cost paper-bridged method for Salmonella phase reversal. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006, 54: 315-317. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.10.009.

CLSI: Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests; approved standard. 2006, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, M2-A9, 9

Kado C, Liu ST: Rapid procedure for detection and isolation of large and small plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1981, 174: 1365-1373.

Chang CC, Lin YH, Chang CF, Yeh KS, Chiu CH, Chu C, Chien MS, Hsu YM, Tsai LS, Chiou CS: Epidemiologic relationship between fluoroquinolone-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Choleraesuis strains isolated from humans and pigs in Taiwan (1997 to 2002). J Clin Microbiol. 2005, 43: 2798-2804. 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2798-2804.2005.

Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, Mickelsen PA, Murray BE, Persing DH, Swaminathan B: Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995, 33: 2233-2239.

Guerin MT, Martin SW, Darlington GA, Rajic A: A temporal study of Salmonella serovars in animals in Alberta between 1990 and 2001. Can J Vet Res. 2005, 69: 88-99.

Eaves-Pyles TD, Wong HR, Odoms K, Pyles RB: Salmonella flagellin-dependent proinflammatory responses are localized to the conserved amino and carboxyl regions of the protein. J Immunol. 2001, 167: 7009-7016.

Gewirtz AT, Simon PO Jr, Schmitt CK, Taylor LJ, Hagedorn CH, O'Brien AD, Neish AS, Madara JL: Salmonella typhimurium translocates flagellin across intestinal epithelia, inducing a proinflammatory response. J Clin Invest. 2001, 07: 99-109. 10.1172/JCI10501.

Zeng H, Carlson AQ, Guo Y, Yu Y, Collier-Hyams LS, Madara JL, Gewirtz AT, Neish AS: Flagellin is the major proinflammatory determinant of enteropathogenic Salmonella. J Immunol. 2003, 171: 3668-74.

Tallant T, Deb A, Kar N, Lupica J, de Veer MJ, DiDonato JA: Flagellin acting via TLR5 is the major activator of key signaling pathways leading to NF-κB and proinflammatory gene program activation in intestinal epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 2004, 4: 33-10.1186/1471-2180-4-33.

Iqbal M, Philbin VJ, Withanage GSK, Wigley P, Beal RK, Goodchild MJ, Barrow P, McConnell I, Maskell DJ, Young J, Bumstead N, Boyd Y, Adrian L, Smith AL: Identification and functional characterization of chicken Toll-like receptor 5 reveals a fundamental role in the biology of infection with Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium. Infect Immun. 2005, 73: 2344-2350. 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2344-2350.2005.

Andersen-Nissen E, Smith KD, Strobe KL, Barrett SLR, Cookson BT, Logan SM, Aderem A: Evasion of Toll-like receptor 5 by flagellated bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005, 102: 9247-9252. 10.1073/pnas.0502040102.

Beal RK, Powers C, Wigley P, Barrow PA, Kaiser P, Smith AL: A strong antigen-specific T-cell response is associated with age and genetically dependent resistance to avian enteric salmonellosis. Infect Immun. 2005, 73: 7509-7516. 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7509-7516.2005.

Beal RK, Powers C, Davison TF, Barrow PA, Smith AL: Clearance of enteric Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in chickens is independent of B-cell function. Infect Immun. 2006, 74: 1442-1444. 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1442-1444.2006.

Chao MR, Hsien CH, Yeh CM, Chou SJ, Chu C, Su YC, Yu CY: Assessing the prevalence of Salmonella enterica in poultry hatcheries by using hatched eggshell membranes. Poult Sc. 2007, 86: 1651-1655.

Angkititrakul S, Chomvarin C, Chaita T, Kanistanon K, Waethwutajarn S: Epidemiology of antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella isolated from pork, chicken meat and humans in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2005, 36: 1510-1515.

Liebana E, Garcia-Migura L, Breslin MF, Davies RH, Woodward MJ: Diversity of strains of Salmonella enterica serotype enteritidis from English poultry farms assessed by multiple genetic fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol. 2001, 39: 154-161. 10.1128/JCM.39.1.154-161.2001.

Chen S, Zhao S, White DJ, Schroeder CM, Lu R, Yang H, McDermott PF, Ayers S, Meng J: Characterization of multiple-antimicrobial-resistant Salmonella serovars isolated from retail meats. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004, 70: 1-7. 10.1128/AEM.70.1.1-7.2004.

White DG, Zhao S, Sudler R, Ayers S, Friedman S, Chen S, McDermott PF, McDermott S, Wagner DD, Meng J: The isolation of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella from retail ground meats. N Engl J Med. 2001, 345: 1147-1154. 10.1056/NEJMoa010315.

Bywater R, Deluyker H, Deroover E, de Jong A, Marion H, McConville M, Rowan T, Shryock T, Shuster D, Thomas V, Vallé M, Walters J: A European survey of antimicrobial susceptibility among zoonotic and commensal bacteria isolated from food-producing animals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004, 54: 744-754. 10.1093/jac/dkh422.

Boyd D, Cloeckaert A, Chaslus-Dancla E, Mulvey MR: Characterization of variant Salmonella genomic island 1 multidrug resistance regions from serovars Typhimurium DT104 and Agona. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002, 46: 1714-22. 10.1128/AAC.46.6.1714-1722.2002.

Levings RS, Djordjevic SP, Hall RM: SGI2, a relative of Salmonella genomic island SGI1 with an independent origin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008, 52: 2529-37. 10.1128/AAC.00189-08.

Havlickova H, Hradecka H, Bernardyova I, Rychlik I: Distribution of integrons and SGI1 among antibiotic-resistant Salmonella enterica isolates of animal origin. Vet Microbiol. 2009, 33: 193-8. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.06.027.

Chen S, Cui S, McDermott PF, Zhao S, White DG, Paulsen I, Meng J: Contribution of target gene mutations and efflux to decreased susceptibility of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium to fluoroquinolones and other antimicrobials. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007, 51: 535-542. 10.1128/AAC.00600-06.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by grants from Council of Agriculture under grant [97 AS-14.6.1-BQ-B4(9)] and National Science Council (NSC96-2314-B-415-001), Executive Yuan, Taiwan (CC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

CC designed, instructed and supervised most aspects of this project. LHC, CYL and CYY collected samples and data analysis of chicken isolates. LHC and CMY did laboratory work and data analysis. JML and SWC performed the experiments and data analysis. CHC and CSC assisted in the design of the study and data analysis of human isolates. CLC, CYY, and CCH gave useful comments and critically read the manuscript. YMH and CPW assisted in animal sampling, data analysis and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12866_2009_1042_MOESM1_ESM.PDF

Additional file 1:Table S1. Association of antibiograms with serogroups among three counties. Antibiograms differed among three counties and serogroups. (PDF 7 KB)

12866_2009_1042_MOESM2_ESM.PDF

Additional file 2:Table S2. Plasmid profiles of serovars in each serogroup. Plasmid profiles determined by size and number was associated with serotypes. (PDF 11 KB)

12866_2009_1042_MOESM3_ESM.PDF

Additional file 3:Figure S1. Representative plasmid profiles of Salmonella isolates collected from chickens. Plasmid size and number of each representative plasmid profile was determined by Kado-Liu method and standard plasmid size of 50 kb and 90 kb plasmid of OU7526. (PDF 202 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Chiu, LH., Chiu, CH., Horn, YM. et al. Characterization of 13 multi-drug resistant Salmonella serovars from different broiler chickens associated with those of human isolates. BMC Microbiol 10, 86 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-10-86

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-10-86