Abstract

Background

General practitioners with more positive role security and therapeutic commitment towards patients with hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption are more involved and manage more alcohol-related problems than others. In this study we evaluated the effects of our tailored multi-faceted improvement implementation programme on GPs’ role security and therapeutic commitment and, in addition, which professional related factors influenced the impact of the implementation programme.

Methods

In a cluster randomised controlled trial, 124 GPs from 82 Dutch general practices were randomised to either the intervention or control group. The tailored, multi-faceted programme included combined physician, organisation, and patient directed alcohol-specific implementation strategies to increase role security and therapeutic commitment in GPs. The control group was mailed the national guideline and patients received feedback letters. Questionnaires were completed before and 12 months after start of the programme. We performed linear multilevel regression analysis to evaluate effects of the implementation programme.

Results

Participating GPs were predominantly male (63%) and had received very low levels of alcohol related education before start of the study (0.4 h). The programme increased therapeutic commitment (p = 0.005; 95%-CI 0.13 – 0.73) but not role security (p = 0.58; 95%-CI −0.31 – 0.54). How important GPs thought it was to improve their care for problematic alcohol consumption, and the GPs’ reported proportion of patients asked about alcohol consumption at baseline, contributed to the effect of the programme on therapeutic commitment.

Conclusions

A tailored, multi-faceted programme aimed at improving GP management of patients with hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption improved GPs’ therapeutic commitment towards patients with alcohol-related problems, but failed to improve GPs’ role security. How important GPs thought it was to improve their care for problematic alcohol consumption, and the GPs’ reported proportion of patients asked about alcohol consumption at baseline, both increased the impact of the programme on therapeutic commitment. It might be worthwhile to monitor proceeding of role security and therapeutic commitment throughout the year after the implementation programme, to see whether the programme is effective on short term but faded out on the longer term.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00298220

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Alcohol consumption is a leading determinant for the global burden of disease [1]. From 20 grams a day, the risk of harm accumulates: risk increases for chronic diseases, cancers, related neuropsychiatric conditions, intoxication, alcoholism, accidents, injuries and violence [2]. Furthermore, the costs related to alcohol are €125 billion a year in Europe for health, welfare, employment and criminal justice sectors as a consequence of alcohol-attributable disease, injury and violence [3]. In this study, safe to moderate consumption corresponds with 2–3 standard drinks per day for men and 1–2 for women, combined with 2 days per week without any consumption and maximum 5 and 3 drinks per occasion for men and women respectively. Hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption was assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), an instrument developed for identification of these conditions. Scores 8–15 and 16–19 correspond with hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption, respectively [4].

Intervening in risky patterns of drinking through screening and brief interventions at an early stage is a cost-effective way to prevent drinking problems [5]. Primary healthcare is very suitable for such interventions because large numbers of patients with a wide range of consumption patterns can be reached [6–10]. Despite the evidence, such screening and brief interventions are rarely implemented into routine clinical practice [11, 12]. Among the reasons most often cited are perceived lack of time, inadequate training, fear of antagonizing clients, the perceived incompatibility of brief alcohol intervention with primary healthcare, and the belief that those who are dependent on alcohol do not respond to interventions [11, 13–15].

The engagement of general practitioners (GPs) in the prevention of alcohol problems can be explained by behavioural theories. The ASE model, which is based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour [16], is one of the models that often has been used to explain behaviours [17, 18]. The model assumes that behaviour can be predicted by the behavioural intention, which is determined by the individual’s Attitude, Social support and self-Efficacy. Moving from professional’s intentions to real actions depends on the person’s abilities and environmental barriers.

There is considerable evidence that GPs with more positive role security and therapeutic commitment towards patients with hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption are more involved and manage more alcohol-related problems than others [19–21]. Anderson et al. [20] have shown that GPs who received more education on alcohol; perceived that they were working in a supportive environment, expressed higher role security in working with alcohol problems, and reported greater therapeutic commitment to working with alcohol problems, were more likely to manage clients with alcohol-related problems. A negative attitude appeared to be an implementation barrier in behavioural change. Their training and support did not improve role security nor therapeutic commitment. The authors recommended that emotional responses of the GPs should be monitored more carefully in future quality improvement programmes, for example through on-site agents or facilitators [20]. Correspondingly, Funk et al. suggested to increase success rates of dissemination of brief interventions that support strategies that address therapeutic commitment, role security and beliefs more profoundly should be explored [22].

To further explore in what way GPs’ role security and therapeutic commitment could be positively influenced, we developed a tailored implementation programme, targeted at role security and therapeutic commitment and incorporated the above recommendations. This multi-faceted alcohol specific implementation strategy included professional, organisational and patient-directed strategies. We aimed to study 1) the effect of a multi-faceted implementation strategy on the providers’ role security and therapeutic commitment towards alcohol-related problems; and 2) other factors which can explain the changes in role security and therapeutic commitment towards alcohol-related problems.

Methods

Design and participants

Data used in this paper were part of the GPA-project (Engaging General Practice in the prevention of patients with Alcohol problems), a cluster randomised controlled trial [23] (trial number NCT00298220). This study assessed the effect of a tailored multi-faceted improvement programme on GPs’ screening of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption and brief intervention rates as well as on role security and therapeutic commitment. Effects of this trial on screening and brief intervention rates and on patient reported alcohol consumption were described elsewhere [4, 23].

Data were collected with measurements before (T0) and 12 months after (T1) delivery of the programme. In total, 2,758 Dutch general practices were invited during three recruitment waves. Practices could only enrol if all GPs in the practice agreed to participate. To encourage enrolment, the non-participants received a reminder after two weeks, and if necessary a second reminder after again two weeks. To encourage response at post measurement, we sent reminders after two and four weeks. Dependent on allocation group and the degree of participation in the different components of the programme, GPs were offered accreditation points, i.e. Permanent Education Points. Dutch clinicians – including GPs – are obliged to achieve sufficient accreditation points in order to maintain their medical license. Accreditation points could be achieved by educational activities and are ultimately granted by a department of the Royal Dutch Medical Association (KNMG).

The trial was approved by the Research Ethics Committee CMO of the region Arnhem-Nijmegen (letter dated 2 January 2006; SE/CMO 0003). The committee concluded in their letter that in compliance with the law on medical–scientific research (WMO), the GPA trial did not need approval. We asked for written informed consent, which was provided by all participants.

Randomisation and allocation

The enrolled practices were randomised by a computerised scheme (block randomisation) to an equal-sized intervention group and control group. Randomisation was done at two moments: after the first two recruitment waves and again after the third wave. The improvement programme was offered to the general practices during October 2006 to June 2007 (intervention period). After randomisation, the practices were divided into clusters for logistic reasons, dependent on their location in the Netherlands. Clusters one through six (all from recruitment wave one or two) started the programme in October 2006 and their last possible activity was in May 2007. Clusters seven and eight (wave three) started the programme in December 2006 and also ended in May 2007. The programme was offered in eight clusters, but the content of those eight clusters was consistent. The research team organised and delivered the intervention, which made it impossible to blind the research team for practice allocation.

Implementation programme

The intervention combined physician, organisation, and patient directed alcohol-specific implementation strategies. The emphasis was on educational training sessions and support visits by a trained facilitator, which were tailored to the providers’ needs and attitudes (see Table 1). The tailoring during training and during support visits was especially focused on the baseline role security and therapeutic commitment of the providers. During the first training session the baseline role security and therapeutic commitment of the providers were discussed and presumptions towards hazardous and harmful levels of alcohol consumption were addressed. Furthermore, the theoretical basics were discussed, i.e. definitions over risky alcohol consumption, epidemiology, risk of alcohol consumption, risk groups, symptoms and possible (brief) interventions. The second and third sessions focused on bringing theory into practice to overcome the barriers that hinder GPs. After a short summary of the theory about how to approach alcohol problems, the participants were able to revert to unfinished matters from the first session of support visit (if attended) or to bring in cases from their daily practice. Next, the GPs practiced motivational interviewing in role plays, a useful method in the treatment of lifestyle problems and disease. The focus in the role plays depended on the role security, therapeutic commitment and experiences of the participating GPs. During support visits barriers of the practice organisation as a whole, were addressed. First, remaining questions after the educational training sessions were discussed. Next, implementation barriers in daily practice were addressed. Besides practical tips to tackle structural, logistical and communication issues, the facilitator focused on the role security and therapeutic commitment of the practice team and discussed individual barriers to act upon alcohol problems. Staff delivering training and support strategies were trained using a detailed standardized protocol and written scripts and guidance.

So, the intervention group received a partly standardised intervention, where education and support were tailored to individual needs. These parts of the programme were tailored as we hypothesised that GPs are more likely to increase their role security and therapeutic commitment in a tailored programme compared to a standardised programme which may not optimally match their baseline rates. Variability within the programme is inherent to tailoring and is expected to result in maximal improvement in role security and therapeutic commitment. Furthermore, physicians as well as patients received feedback from patient AUDIT scores [23], through personal feedback. For a detailed outline of the programme, see Table 1.

The control group was mailed the national guideline [24] (which was publicly available) and patient information letters on problematic alcohol consumption developed by the Dutch College of General Practitioners in order to distribute to patients by GPs when appropriate. The GPs did not receive further support or training. For ethical reasons, the patients also had to receive the personalised feedback on alcohol consumption in May 2007, which can be assessed as a minimal intervention, but took place after the physician programme ended.

Outcome measurements

This paper describes outcomes on the GPs’ role security and therapeutic commitment. These were measured before and after the implementation programme, using the 10-item Shortened Alcohol and Alcohol Problems Perception Questionnaire (SAAPPQ). The SAAPPQ has been developed in England as a quick yet meaningful measure of GPs’ attitudes to working with drinkers, either as a way of measuring change over time or when planning intervention strategies [25]. We translated the questionnaire into Dutch, and independently back-translated it into English to check accuracy of the initial translation, both literally and idiomatically.

The role security domain within the SAAPPQ includes 2 sub-domains: role adequacy, and role legitimacy (e.g. “I feel I can appropriately advise my patients about drinking and its effects”; “I feel I have the right to ask patients questions about their drinking when necessary”). Therapeutic commitment involves motivation, task specific self-esteem, and work satisfaction. Within the scales of role security and therapeutic commitment (ratings on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’) means were calculated. For the questions of the SAAPPQ with additional scoring key, see Additional file 1.

Additionally, we added questions to the pre-measurement questionnaire about the providers’ characteristics, such as age, gender, practice size (number of patients per physicians), full-time equivalent (FTE), and the degree of urbanisation of the practice. Moreover, we asked how important GPs thought it was to improve their identification of patients with alcohol-related problems (both before and after intervention), how important GPs thought it was to improve care for patients with alcohol-related problems (both before and after intervention), degree of alcohol-related education, the GPs’ reported proportion of patients asked about their alcohol consumption (both before and after intervention), proportion of patients counselled by the GP for alcohol-related problems (both before and after intervention), degree of participation in the intervention programme, and correct or incorrect estimating the maximum number of drinks by the guideline (both before and after intervention). The post measurement questionnaire was similar although questions about provider characteristics such as practice type, patient load, etc. were excluded.

Sample size

A power calculation was carried out to estimate the number of practices to be included to detect the effect of the implementation programme in changing providers’ advice giving behaviour and is described elsewhere [23]. We intended to recruit 80 general practices.

Statistical analysis

Practice was the unit of allocation. Because of the hierarchical structure (GPs nested within practices), we performed a linear multilevel (mixed model) analysis. In this analyses we take account of the variability associated with each level of nesting. In a mixed model both fixed and random effects can be analysed. We performed a model with a random intercept for practices and all other variables fixed, as these were used to correct the effect. Subsequently, we investigated the effect of the implementation programme on domains of role security and therapeutic commitment as a continuous outcome variable. Multilevel linear regression analysis with the follow up score as outcome and baseline score as covariate was used to evaluate the effect of the implementation programme. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the characteristics of participating GPs at baseline.

During the second wave, the SAAPPQ had a systematic flaw. The last SAAPPQ-question “In general, I like drinkers” was systematically missing and caused a missing value, concerning 67 GPs. All participants that had missings in their measurements, were assigned a value based on multiple imputation procedure. All of the potential determinants of effects were used for calculating the imputation. It is suggested that multiple imputation yields less bias and less variability than the often used last observation carried forward method [26]. Before the multiple imputation, we checked all the variables in the absence of a significant difference between the group with the systematic missing (i.e. second wave), to the group without the significant missing (i.e. first and third wave). After multiple imputation, the sample did not significantly differ from the former sample without multiple imputation. To maintain the power, we decided to proceed with the multiple imputation sample.

We added the following factors from baseline separately to explain the changes in the effects on role security and therapeutic commitment towards alcohol-related problems, as we thought they might determine the effect of the implementation programme: age, gender, full time equivalent, size of patient population, working area, practice setting (solo, duo, group, etc.), how important GPs thought it was to improve their identification of patients with alcohol-related problems (both before and after intervention), how important GPs thought it was to improve care for patients with alcohol-related problems (both before and after intervention), degree of alcohol-related education, the GPs’ reported proportion of patients asked about their alcohol consumption (both before and after intervention), proportion of patients counselled by the GP for alcohol-related problems (both before and after intervention), degree of participation in the intervention programme, and correct or incorrect estimating the maximum number of drinks by the guideline (both before and after intervention). Furthermore, we added interaction terms in order to identify interactive effect of the programme (effect modification). We considered a p-value < 0.05 statistically significant. Descriptive analyses was conducted using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM PASW statistics 20) and multilevel regression analyses was conducted using SAS V9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Study population

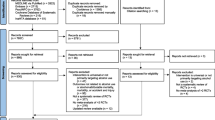

Figure 1 outlines the study design and the flow of participating practices and GPs. The participating 82 practices with 124 GPs were randomised. After randomisation but before pre measurement, five practices withdrew: one in the intervention group and four in the control group (no data available). This resulted in 40 practices (63 GPs) receiving allocated intervention and 37 practices (56 GPs) in the control group.

With regard to the baseline and follow-up measurement, 112 GPs delivered sufficient information to be included in the analysis: 59 in the intervention group and 53 in the control group.

Descriptive demographics of the GPs are detailed in Table 2. GPs of the intervention and control group only significantly differed in age: GPs of the intervention group turned out to be on average 4 years younger than their colleagues in the control group, but in both groups the majority of GPs was middle-aged (45–50 years).

Table 2 also includes baseline role security and therapeutic commitment. The role security and therapeutic commitment levels of the control group are not different compared to the intervention group. For results on the 10 single SAAPPQ questions from which role security and therapeutic commitment in Table 2 were calculated, see Additional file 2.

Non-participants

The non-participant questionnaire was returned by 761 GPs (28%). As to age, average percentage of fulltime work, caseload, and working area the participating GPs did not differ from the non-participants (see Table 2). However, the non-participating GPs worked on average in practices with more colleagues than the participating GPs, who mostly worked in solo- or duo practices (p < 0.05). Moreover, the non-participant population consisted of more male GPs compared to the participating population, but just with a 2% difference (p < 0.05). Non-participant role security and therapeutic commitment did not differ from participant baseline levels. For results on the 10 single SAAPPQ questions from which role security and therapeutic commitment were calculated, see Additional file 2.

Changes in role security and therapeutic commitment

Table 3 shows scores before and after the implementation of the programme, and the mean difference for role security and therapeutic commitment, respectively. GPs in both intervention and control groups improved in their role security and therapeutic commitment, though the intervention group showed a higher mean score.

Corrected for baseline levels, Table 4 shows the results of the multilevel analysis without and with multiple imputation for both role security and therapeutic commitment respectively. From this table we can see there were no major changes in parameters, which allows us to proceed with the multiple imputation model. The multilevel regression analysis showed that GPs in the intervention group improved in their therapeutic commitment more than 0.43 on the 7-point likert scale (95%-CI 0.13-0.73) compared to GPs in the control group. On the contrary, role security did not significantly change due to the intervention (β = 0.11; p = 0.58; 95%-CI −0.31-0.54).

Explaining changes in role security and therapeutic commitment change

With regard to therapeutic commitment, how important GPs thought it was to improve their care for problematic alcohol consumption, and the GPs’ reported proportion of patients asked about alcohol consumption at baseline, were identified as likely determinants of effects (p < 0.15). The results from Table 5 show that, corrected for these both factors, the intervention effect further increased compared to the uncorrected intervention effect from 0.43 to 0.51 points within therapeutic commitment.

Role security did not improve due to the implementation programme. The degree of participation in the intervention programme was identified as a likely determinant of effect (p < 0.15), but the intervention effects remained to be non-significant. This implies that the programme did not affected role security neither in a negatively, nor positively.

Furthermore, we were not able to identify subgroups in intervention effects in terms of effect modification. Neither in the effect of the implementation programme on role security, nor on therapeutic commitment, interactive effects between potential determinants of effect could be identified.

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that our implementation programme improved the GPs’ therapeutic commitment, but despite all efforts for tailoring the intervention to the providers, it did not affect the role security. In line with this latter finding, the tailored implementation programme neither improved GPs’ screening and brief intervention rates, as described elsewhere [23].

How important GPs thought it was to improve their care for problematic alcohol consumption, and the GPs’ reported proportion of patients asked about alcohol consumption at baseline, were identified as determinants of effects on the therapeutic commitment. Nevertheless, when corrected for this, the programme remained to be effective in improving therapeutic commitment. With regard to role security, no determinants of effects were identified.

Our findings do not confirm our hypothesis that our tailored implementation programme would improve GPs’ role security, despite the efforts for tailoring to providers’ baseline role security. Role security is about having knowledge and skills in recognising and discussing risky alcohol consumption and role legitimacy. Looking at the professional-oriented elements of the programme that could have influenced role security, the educational sessions and support visits were tailored to the GPs’ SAAPPQ baseline scores in the sense that the outcomes of the SAAPPQ were discussed and presumptions towards hazardous and harmful levels of alcohol consumption were addressed. A possible explanation for improvement of therapeutic commitment and not for role security might be the fact that the baseline level of role security was higher than the level of therapeutic commitment, and was therefore leaving less room for improvement. Another reason for not showing a substantial improvement of role security might be that follow-up was measured only after 12 months. An initial effect on role security might have faded out by that time. Additionally, in line with our finding that the programme did not increase role security, was the fact that the study results did not show improved screening and brief intervention rates. The screening and brief intervention rates were initially improved during the implementation period, but the effects deteriorated at the end, i.e. there was no difference between the intervention group and control group [23]. This may imply that only if both role security and therapeutic commitment are improved this will have an impact on provider behaviour. Furthermore, when looking at the two sub-domains within role security, one could expect it to be easier to improve role adequacy (knowledge and skills) than role legitimacy (Additional file 1). The results indeed showed a larger improvement in role adequacy than in role legitimacy, however the difference was not sufficient to draw any firm conclusions from. It might be indicating however that more attention needs to be given to enhancing role legitimacy.

Also, similar to our findings, Anderson et al. found that training and support did not increase role security. In fact, they even found that role security and therapeutic commitment for GPs who were already role-insecure and low therapeutically committed, actually deteriorated [20]. We cannot confirm this finding that experience in screening and brief interventions deteriorates role security in GPs who were already insecure in their role, though we saw that how important GPs thought it was to improve their care for problematic alcohol consumption, and the GPs’ reported proportion of patients asked about alcohol consumption at baseline, facilitated improvement of therapeutic commitment. Tailoring the intervention to the GPs’ levels of role security, as we did, however, might not be sufficient to actually improve role security and subsequently screening and brief intervention behaviour. In the study of Butler et al. [27], it was emphasised to not just tell GPs to incorporate behaviour change counselling into their consults, but training requires more finesse in the sense that perceptions and the internally-driven processes of GPs are addressed in the training and support sessions. We think our study incorporated those elements, this may explain why we succeeded in improving therapeutic commitment.

Although the participants were only a small proportion of the total population, they largely reflected key characteristics of GPs in The Netherlands. Only on the aspect of gender and on practice type, there was just a small difference between participating and non-participating GPs. This means that it is very likely that our results are representative for the Dutch GP population. This is interesting, since the recruitment of practices was laborious and we had to invite more practices than anticipated. Experiences from colleagues in international clinical trials learn us that it is increasingly difficult to recruit and retain GPs for clinical trials [28–31].

On the other side, a limitation of our study was the very limited degree of participation of the GPs in the training sessions and visits: only 59% of GPs from the intervention group met the minimal demands of enrolment. This possibly means that the acceptability of the implementation programme was suboptimal. Furthermore, we were not able to identify different effects of the implementation programme between subgroups of patients (i.e. effect modification). It is likely that the sample size was too small to detect possible effect modification. Besides, during a systematic flaw of missing a question in a part of the questionnaires, we required multiple imputation to maintain as much power as possible. However, after checking whether multiple imputation affected the results, there were no signs of any affected results.

Although we have shown that it is possible to improve GPs’ therapeutic commitment, it was described in an earlier published article of this study that the implementation programme neither produced improved screening and brief intervention outcomes at the GP level [23], nor on the level of patient alcohol consumption [4] both at one year follow-up. Like suggested in an earlier article of this GPA-project [23], this does not necessarily mean that the implementation programme did not work, as the transtheoretical model of (health) behaviour change suggests that it can take up to five years for new behaviour to be integrated in daily routines [32]. Also, as researchers we might be too keen on having effects from implementation strategies, which results in high expectations and ambitious, high intensity implementation programmes. Probably it is more effective to take very small steps in the process of GPs incorporating prevention activities, since their practice actually is more focused on the disease model. That means that we should think about other strategies to increase role security and therapeutic commitment, find out the optimal measurement times and frequencies, and create long-term trials to monitor role security, therapeutic commitment and in the end screening and brief interventions against hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption.

Furthermore, research implementation programmes could focus on letting the implementation strategy for screening and brief interventions match as much as possible to GPs’ current practice in a way of achieving ‘personalised implementation’ , which likely is to be focused on the disease model. In addition, if it remained to be difficult to improve GPs’ readiness to screen and do brief interventions, one might not use (solely) professional oriented implementation strategies aimed at GPs, but on the contrary test the effect of organisational oriented implementation strategies like physically locating addiction care in the general practice or test the effect of substitution of preventive tasks from the GP to practice nurses. The latter might be a more low-threshold intervention. There are studies that already evaluated the effects of nurses’ SBI (e.g. [33–35]), this research could be extended with evaluating task substitution from the GP to the nurse.

Lastly, it would be worthwhile to gain more insight of the GPs’ attitudes over time. We had a long time between the first and last measurement, which resulted in a kind of ‘black box’ with regard to the attitude in due course. If it was shown that the effects faded out in time, a short booster programme may be effective in maintaining improved role security and therapeutic commitment, and maybe even maintaining improved screening and advice giving behaviour.

Conclusions

A tailored, multi-faceted programme aimed at improving GP management of patients with hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption improved GPs’ therapeutic commitment towards patients with alcohol-related problems, but failed to improve GPs’ role security. How important GPs thought it was to improve their care for problematic alcohol consumption, and the GPs’ reported proportion of patients asked about alcohol consumption at baseline contributed to the effect of the programme on therapeutic commitment. It might be worthwhile to monitor proceeding of role security and therapeutic commitment throughout the year after the implementation programme, to see whether the programme is effective on short term but faded out.

Abbreviations

- GP:

-

General practitioner

- GPA:

-

Engaging General Practice in the prevention of patients with Alcohol problems

- SAAPPQ:

-

Shortened Alcohol and Alcohol Problems Perception Questionnaire.

References

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, Amann M, Anderson HR, Andrews KG, Aryee M, Atkinson C, Bacchus LJ, Bahalim AN, Balakrishnan K, Balmes J, Barker-Collo S, Baxter A, Bell ML, Blore JD, Blyth F, Bonner C, Borges G, Bourne R, Boussinesq M, Brauer M, Brooks P, Bruce NG, Brunekreef B, Bryan-Hancock C, Bucello C: A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2013, 380: 2224-2260.

World Health Organization: Alcohol in the European Union. Consumption, Harm and Policy Approaches. Alcohol in the European Union. Consumption, harm and policy approaches. Edited by: Anderson P, Møller L, Galea G. 2012, Copenhagen: WHO Regional office for Europe

Anderson P, Baumberg B: Alcohol in Europe. 2006, London: Institute of Alcohol Studies

Hilbink M, Voerman G, van Beurden I, Penninx B, Laurant M: A randomized controlled trial of a tailored primary care program to reverse excessive alcohol consumption. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012, 25: 712-722. 10.3122/jabfm.2012.05.120070.

Kaner EF, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, Pienaar E, Campbell F, Schlesinger C, Heather N, Saunders J, Burnand B: Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, Art. no.: CD000409-doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000409.pub2

Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC: Alcohol screening and brief intervention: dissemination strategies for medical practice and public health. Addiction. 2000, 95: 677-686. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9556773.x.

Anderson P: The Effectiveness of General practitioners’ Advice in Reducing the Risk of Alcohol. Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: An Evidence-Based Approach. Edited by: Lawrence M, Neil A, Fowler G, Mant D. 1996, Oxford: Oxford University Press, Volume 2

Fleming MF, Mundt MP, French MT, Manwell LB, Stauffacher EA, Barry KL: Benefit-cost analysis of brief physician advice with problem drinkers in primary care settings. Med Care. 2000, 38: 7-18. 10.1097/00005650-200001000-00003.

Fleming MF, Mundt MP, French MT, Manwell LB, Stauffacher EA, Barry KL: Brief physician advice for problem drinkers: long-term efficacy and benefit-cost analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002, 26: 36-43. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2002.tb02429.x.

Ernst D, Miller WR, Rollnick S: Treating substance abuse in primary care: a demonstration project. Int J Integr Care. 2007, 7: e36-

Spandorfer JM, Israel Y, Turner BJ: Primary care physicians’ views on screening and management of alcohol abuse: inconsistencies with national guidelines. J Fam Pract. 1999, 48: 899-902.

Anderson P: Overview of interventions to enhance primary-care provider management of patients with substance-use disorders. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009, 28: 567-574. 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00113.x.

Kaner EF, Heather N, McAvoy BR, Lock CA, Gilvarry E: Intervention for excessive alcohol consumption in primary health care: attitudes and practices of english general practitioners. Alcohol Alcohol. 1999, 34: 559-566. 10.1093/alcalc/34.4.559.

Babor TE, Higgins-Biddle J, Dauser D, Higgins P, Burleson JA: Alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care settings: implementation models and predictors. J Stud Alcohol. 2005, 66: 361-368.

Nilsen P: Brief alcohol intervention–where to from here? Challenges remain for research and practice. Addiction. 2010, 105: 954-959. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02779.x.

Ajzen I: The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Dec. 1991, 50: 179-211. 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

De Vries H, Mudde AN, Leijs I, Charlton A, Vartiainen E, Buijs G, Clemente MP, Storm H, Gonzalez Navarro A, Nebot M, Prins T, Kremers S: The European smoking prevention framework approach (ESFA): an example of integral prevention. Health Educ Res. 2003, 18: 611-626. 10.1093/her/cyg031.

De Vries H: Determinanten van Gedrag [Determinants of Behaviour]. Gezondheidsvoorlichting en Gedragsverandering. Health Education and Behavioural Change. Edited by: Damoiseaux V, Van der Molen HT, Kok GJ. 1993, Assen: Van Gorcum, 109-132.

Shaw S, Cartwright A, Spratley T, Harwin J: Responding to Drinking Problems. 1978, London: Croom Helm

Anderson P, Kaner E, Wutzke S, Funk M, Heather N, Wensing M, Grol R, Gual A, Pas L: Attitudes and managing alcohol problems in general practice: an interaction analysis based on findings from a WHO collaborative study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004, 39: 351-356. 10.1093/alcalc/agh072.

McCormick KA, Cochran NE, Back AL, Merrill JO, Williams EC, Bradley KA: How primary care providers talk to patients about alcohol: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006, 21: 966-972. 10.1007/BF02743146.

Funk M, Wutzke S, Kaner E, Anderson P, Pas L, McCormick R, Gual A, Barfod S, Saunders J: A multicountry controlled trial of strategies to promote dissemination and implementation of brief alcohol intervention in primary health care: findings of a world health organization collaborative study. J Stud Alcohol. 2005, 66: 379-388.

van Beurden I, Anderson P, Akkermans RP, Grol RP, Wensing M, Laurant MG: Involvement of general practitioners in managing alcohol problems: a randomised controlled trial of a tailored improvement programme. Addiction. 2012, 107: 1601-1611. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03868.x.

Meerkerk GJ, Aarns T, Dijkstra RH, Weisscher P, Njoo K, Boomsma LJ: NHG-standaard problematisch alcoholgebruik (tweede herziening). Huisarts Wet. 2005, 48: 284-285.

Anderson P, Clement S: The AAPPQ revisited: the measurement of general practitioners’ attitudes to alcohol problems. Br J Addict. 1987, 82: 753-759. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01542.x.

Dinh P: Using multiple imputation to estimate cumulative distribution functions in longitudinal data analysis with data missing at random. Pharm Stat. 2013, 12: 260-267. 10.1002/pst.1579. doi: 210.1002/pst.1579. Epub 2013 Jul 1004

Butler CC, Simpson SA, Hood K, Cohen D, Pickles T, Spanou C, McCambridge J, Moore L, Randell E, Alam MF, Kinnersley P, Edwards A, Smith C, Rollnick S: Training practitioners to deliver opportunistic multiple behaviour change counselling in primary care: a cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2013, 346: f1191-10.1136/bmj.f1191.

Franke L, Kommers T, Van Weel E, Lucasson P, Beek M, Van den Hoogen H, Van Weel C: General practice registrars and research - attitudes toward participation. Aust Fam Physician. 2008, 37: 276-279.

Leathem CS, Cupples ME, Byrne MC, O’Malley M, Houlihan A, Murphy AW, Smith SM: Identifying strategies to maximise recruitment and retention of practices and patients in a multicentre randomised controlled trial of an intervention to optimise secondary prevention for coronary heart disease in primary care. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009, 9: 40-10.1186/1471-2288-9-40.

van der Wouden JC, Blankenstein AH, Huibers MJ, van der Windt DA, Stalman WA, Verhagen AP: Survey among 78 studies showed that Lasagna’s law holds in dutch primary care research. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007, 60: 819-824. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.11.010.

Veitch C, Hollins J, Worley P, Mitchell G: General practice research. Problems and solutions in participant recruitment and retention. Aust Fam Physician. 2001, 30: 399-406.

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF: The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997, 12: 38-48. 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38.

Kaner E, Lock C, Heather N, McNamee P, Bond S: Promoting brief alcohol intervention by nurses in primary care: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2003, 51: 277-284. 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00242-2.

McElwaine KM, Freund M, Campbell EM, Slattery C, Wye PM, Lecathelinais C, Bartlem KM, Gillham KE, Wiggers JH: Clinician assessment, advice and referral for multiple health risk behaviors: prevalence and predictors of delivery by primary health care nurses and allied health professionals. Patient Educ Couns. 2013, 94 (2): 193-201.

Reiff-Hekking S, Ockene JK, Hurley TG, Reed GW: Brief physician and nurse practitioner-delivered counseling for high-risk drinking: results at 12-month follow-up. J Gen Intern Med. 2005, 20 (1): 7-13. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.21240.x.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2296/15/70/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff and patients in general practices for participating in this trial, and the GP-trainers and the facilitator who visited the intervention practices. We would also like to thank the research assistants who helped with the overall data management and with the extraction of data in general practices. We also thank the Dutch College of General Practitioners (NHG), National Institute for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention (NIGZ) and Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction (Trimbos Institute) for their advice on the development of the multi-faceted strategy and the opportunity to use their educational materials freely. This study was supported by a grant from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), dossier number 63000003. No author or related institution has received any financial benefit from research in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ML, PA and MW were responsible for designing the study protocol and set up of the implementation programme. IvB conducted the study. MK and RA analysed the data and interpreted the results. MK drafted the first manuscript, critically revised the draft manuscripts. ML and MH assisted with the in interpretation of the results and the drafting the manuscripts. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12875_2014_1044_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: The SAAPPQ questionnaire (English version) with scoring key. This file shows the 10 single SAAPPQ questions and includes the scoring key for calculating role security and therapeutic commitment. (DOCX 14 KB)

12875_2014_1044_MOESM2_ESM.docx

Additional file 2: Baseline role security and therapeutic commitment of participating and non-participating GPs. This file shows baseline results from the 10 single SAAPPQ questions, from which the Table 2 role security and therapeutic commitment were calculated. (DOCX 14 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Keurhorst, M., van Beurden, I., Anderson, P. et al. GPs’ role security and therapeutic commitment in managing alcohol problems: a randomised controlled trial of a tailored improvement programme. BMC Fam Pract 15, 70 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-15-70

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-15-70