Abstract

Background

An imbalance between proliferation and apoptosis is one of the main features of carcinogenesis. TRAIL (TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand) induces apoptosis upon binding to the TRAIL death receptors, TRAIL receptor 1 (TRAIL-R1) and TRAIL-R2, whereas binding to TRAIL-R3 and TRAIL-R4 might promote cell survival and proliferation. The anti-tumor activity of TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 agonists is currently investigated in clinical trials. To gain further insight into the regulation of apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), we investigated the TRAIL pathway and the regulators of apoptosis caspase-8, Bcl-xL and Mcl-1 in patients with HCC regarding patient survival.

Methods

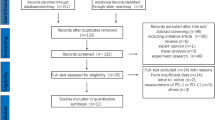

We analyzed 157 hepatocellular carcinoma patients who underwent partial liver resection or orthotopic liver transplantation and healthy control liver tissue using immunohistochemistry on tissue microarrays for the expression of TRAIL-R1 to TRAIL-R4, caspase-8, Bcl-xL and Mcl-1. Immunohistochemical data were evaluated for potential associations with clinico-pathological parameters and survival.

Results

Whereas TRAIL-R1 was downregulated in HCC in comparison to normal liver tissue, TRAIL-R2 and –R4 were upregulated in HCC, especially in G2 and G3 tumors. TRAIL-R1 downregulation and upregulation of TRAIL-R2 and TRAIL-R4 correlated with tumor dedifferentiation (G2/G3). TRAIL-R3, Bcl-xL and Mcl-1 showed no differential expression in tumor tissue compared to normal tissue. The expression levels of TRAIL receptors did not correlate with patient survival after partial hepatectomy. Interestingly, in tumor tissue, but not in normal hepatocytes, caspase-8 showed a strong nuclear staining. Low cytosolic and high nuclear staining intensity of caspase-8 significantly correlated with impaired survival after partial hepatectomy, which, for cytosolic caspase-8, was independent from tumor grade.

Conclusions

Assessment of TRAIL-receptor expression patterns may have therapeutic implications for the use of TRAIL receptor agonists in HCC therapy. Tumor-specific nuclear localisation of caspase-8 in HCC suggests an apoptosis-independent function of caspase-8 and correlates with patient survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the main type of primary liver cancer and the fifth most common malignant cancer worldwide. Its poor prognosis makes it the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality [1–3]. Only about 30% of patients are eligible for curative therapies (e.g. resection and transplantation) and the disease recurs frequently following liver resection [4]. Sorafenib, an oral multikinase inhibitor, is effective in the treatment of advanced HCC [5]. However, sorafenib therapy is limited by side effects and lack of long-term efficacy.

The tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis inducing-ligand (TRAIL) is a member of the TNF cytokine family. TRAIL is currently in clinical development as a potential novel anticancer therapeutic because it selectively induces apoptosis in cancer cells [6–11]. After TRAIL-binding TRAIL-R1, also called Death Receptor 4 (DR4), [12] and TRAIL-R2 (DR5) [13, 14] initiate apoptosis following formation of the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC): trimerization of TRAIL-R1 and/or TRAIL-R2 leads to recruitment of FADD and cytoplasmic caspase-8 to the intracellular death domain (DD) of both receptors. Caspase-8 recruitment to the DISC activates this protease, which triggers a caspase cascade and, ultimately, apoptotic death of susceptible cells. Two other receptors, TRAIL-R3 and TRAIL-R4, do not induce apoptosis; they lack a functional intracellular death domain [15–17] and have been suggested to inhibit TRAIL-induced apoptosis by competing with TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 for TRAIL-binding. TRAIL-R4 has also been shown to inhibit apoptosis through ligand-independent association with TRAIL-R2 via the preligand assembly domain (PLAD) [18] or by NF-κB activation upon TRAIL-R4 overexpression [17]. The fifth TRAIL-receptor, osteoprotegerin, is a soluble receptor and is mainly involved in the regulation of bone metabolism [19, 20].

Apart from representing potential therapeutic targets for novel, TRAIL-based therapies, the two TRAIL receptors and their expression pattern may be both prognostic and predictive for patient survival. However, the currently available data is controversial in this regard. For instance, in renal cell carcinoma high TRAIL-R2 and low TRAIL-R4 expression correlated with poorer overall survival [21]. In breast cancer, expression of TRAIL-R2 was associated with TRAIL-R4 positivity and correlated with poorer survival [22]. In contrast, in colorectal cancer Ullenhag et al. could not detect any correlation of TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 expression status with patients survival [23].

Caspase-8 is crucial for triggering apoptosis by death receptors since its recruitment to and activation at the DISC is the decisive step for the initiation of the caspase cascade [24]. Besides apoptosis induction non-apoptotic functions of caspase-8 have been discussed, although these non-apoptotic signaling pathways and molecular targets have not been defined yet [25]. Bcl-xL and Mcl-1 belong to the anti-apoptotic B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) family of proteins [26]. High expression of Bcl-XL has been associated with more aggressive tumor biology and/or drug resistance to various chemotherapeutic agents in hematologic and solid malignancies [26]. Inhibition of Bcl-xL induces apoptosis and suppresses growth of hepatoma cells in combination with sorafenib [27]. Mcl-1 is overexpressed in about 50% of HCC tissues [28] but on the other hand deletion of Mcl-1 triggers hepatocarcinogenesis in mice [29]. Recent studies have demonstrated that TRAIL expression is altered in HCC in comparison to normal liver tissue, but there are contradictory data about the expression of the different TRAIL receptors in HCC cells and tissues [30–34]. Thus, we analyzed TRAIL receptors and the apoptosis regulatory proteins caspase-8, Bcl-xL and Mcl-1 in correlation with HCC grading and survival.

Methods

Patient characteristics

To analyze the expression of TRAIL receptors, caspase-8, Bcl-xL and Mcl-1 HCC tumor samples were obtained from patients with HCC (n = 157) who underwent orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT, n = 82, 52%) or partial resection (PR, n = 75, 48%) between 1997 and 2005. Median age of the patients was 58 years. 27% suffered from alcohol-induced liver disease, 40% had chronic viral hepatitis. 41 (55%) of the patients undergoing partial liver resection suffered from cirrhosis. Detailed patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Survival analysis was carried out in 49 patients who underwent partial resection. Of the 75 patients who underwent partial resection, seven were excluded from the survival analysis because they died within the first month after surgery, not related to HCC; 19 patients were lost during follow up. OLT patients were excluded from survival analysis since survival after OLT is mainly influenced by non-tumor-related factors.

Histopathological data

Normal liver tissue was obtained from liver resections from patients without underlying liver disease who underwent resection for other reasons than HCC, i.e. liver metastasis. All specimens were resected at the Dept. of General and Transplant Surgery, University of Heidelberg. Histopathological data were obtained from the Institute of Pathology, University Hospital of Heidelberg and were reviewed by at least two board-certified pathologists experienced in liver pathology. A total of 157 human liver tissue samples were evaluated by tissue microarrays (TMAs). TMAs contained two representative areas of hepatocellular carcinoma of each patient or normal liver (punch cylinder diameter: 0.6 mm). All specimens were fixed in 4% formalin (pH 7.4) and embedded in paraffin. Grading was determined based on the AFIP system [35]. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the medical faculty of Heidelberg University (206/2005).

Antibodies and reagents

For specific immunohistochemical detection of TRAIL receptors we used the following mouse IgG antibodies as described before [22]: TR1.02 (TRAIL-R1; mIgG2b), TR2.21 (TRAIL-R2; mIgG1), TR3.06 (TRAIL-R3; mIgG1) and TR4.18 (TRAIL-R4; mIgG1). The antibody C-15 (caspase-8, mIgG2b) was kindly provided by P.H. Krammer (DKFZ, Heidelberg). Furthermore, the following antibodies were used: 2H212 (Bcl-xL, mIgG2a, Zytomed, Berlin, Germany), S-19 (Mcl-1, rabbit polyclonal IgG, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), C92-605 (active caspase-3, BD Biosciences, San Jose, USA), 18C8 (active caspase-8, Cell Signalling, Danvers, MA, USA). Super-Sensitive Detection Kit from BioGenex (Fremont, CA, USA) was used for detection. The specificity of immunohistochemical stainings of the different anti-TRAIL-R mAbs was determined by staining of sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded pellets of CV1 cells transfected with pCDNA3.1-based expression vectors for TRAIL-R1 to TRAIL-R4 as described previously [22]. For TRAIL-R1 staining with TR1.02, a high temperature antigen retrieval step was performed by incubating in 10 mM citrate buffer (Target Retrieval Solution, S1699 DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) at pH 6.0 at 89°C for 15 min. For paraffin sections stained for TRAIL-R2 with TR2.21, TRAIL-R3 with TR3.06 and TRAIL-R4 with TR4.18, antigen retrieval was achieved by incubation in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 99°C for 25 min. For Bcl-xL antigen demasking was performed by incubation in EDTA (1 mM, pH 8.0) at 99°C for 15 min. For staining with the other antibodies antigen demasking was performed in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 99°C for 25 min. To block non-specific antibody binding, sections were incubated with blocking solution 1 (PBS, BSA 20 mg/ml (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany), human IgG 1 mg/ml Gamma-Venin, (Aventis Behring, Marburg, Deutschland)) for 20 min. Sections were then incubated in the presence of the first antibody at room temperature for one hour (caspase-8: 10 μg/ml, Bcl-xL: 7 μg/ml, Mcl-1: 0,5 μg/ml) or at 4°C in blocking solution overnight (TRAIL-R1: 20 μg/ml, TRAIL-R2: 5 μg/ml, TRAIL-R3: 10 μg/ml, TRAIL-R4: 5 μg/ml) or isotype-matched antibodies (IgG1 or IgG2b) at the same concentration, both obtained from DakoCytomation. Sections were washed twice in PBS and incubated with blocking solution 2 (20% normal goat serum from Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) for 20 min. After blocking, sections were incubated with secondary biotinylated antibody at room temperature for 30 min, rinsed twice for 5 min in PBS and incubated for 30 min with streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase [Super-Sensitive Detection Kit, BioGenex]. Thereafter, sections were rinsed twice in PBS, incubated with fast red substrate (Fast Red Substrate System, DakoCytomation) and counterstained with haematoxylin (DakoCytomation).

Histopathological scoring and statistics

A two-dimensional scoring system was applied to semi-quantitatively assess the expression of the respective protein. The percentage of positive cells was estimated by two independent investigators on a scale from 0 to 100% and categorised from 0–4 (0 = 0, 1 = up to 1%, 2 = 1-10%, 3 = 10-50%, 4 = more than 50%). Intensity of staining (intensity score) was judged on an arbitrary scale of 0 to 4: no staining (0), weak positive staining (1), moderate positive staining (2), strong positive staining (3) and very strong positive staining (4) as described by Zhuang et al. [36] and applied to tumor tissue arrays [22]. The immunoreactive score (IRS) was calculated by multiplying the percentage of positive cells (0–4, according to the categorised percentages of positive cells) with staining intensity (0–4, according to the category of staining intensity). For instance, a tumor sample with 60% of positive tumor cells (=category 4 for “percentage of positive cells”) with a very strong staining (=category 4 for “staining intensity”) will result in an IRS of 4 × 4 = 16, which represents the maximum IRS. From each tumor, two samples were spotted and analyzed on the tissue microarray (TMA). The final IRS of each patient was calculated as the mean of the two investigator’s analyses of both tumor samples.

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software (Release 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare the immunohistochemical score of TRAIL receptors and key proteins between tumor and normal liver tissue and graphically represented in Box plots. Comparisons of the immunohistochemical score between more than two subgroups were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Linear correlation between nuclear/cytosolic caspase-8 expression and Ki67/apoptosis rate was performed using the Spearman correlation coefficient and the corresponding p-value. Overall survival was defined as the time from the date of tumor staging to either death from any cause or last follow-up. Patients alive at the last follow-up were censored. Survival curves were constructed by using the Kaplan-Meier estimate. The 1-, 2-, 5-, and 10-year survival rates and the median survival time are presented. Differences between survival curves of subgroups of patients were analyzed by the log-rank test. The immunohistochemical scores for TRAIL-R1 to TRAIL-R4 and caspase-8 were dichotomized for survival analysis according to the quartiles and the median of the distribution of the score values to ensure a sufficient number of patients in the resulting subgroups. The Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to analyze the correlation of survival and expression of TRAIL receptors, other key proteins, and histopathological parameters. Two sided p values were always computed and p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

We compared the expression profile of TRAIL-R1 to TRAIL-R4, caspase-8, Bcl-xL and Mcl-1 in HCC in comparison to normal liver tissue. All TRAIL receptors showed both cytoplasmic and membranous staining, although membrane staining was rather faint and therefore not quantified. Survival in correlation with the immunohistochemical staining result was analyzed in 49 patients who underwent partial liver resection (see Material and Methods). Overall survival rates of these patients were 75.5%, 52.6%, 34.7% and 18.1% after one, three, five, and ten years, respectively. Median survival was 42 months (Figure 1A). Survival rates were poorer in patients with G3 tumors compared to G1 and G2 tumors (Figure 1B).

Investigating the expression level of caspase-8, we found a differential expression of caspase-8 in the cytosol versus nucleus of tumor cells (examples presented in Figure 2). Thus, the cytosolic and nuclear expression patterns of caspase-8 were analyzed separately in the subsequent investigations.

Expression levels of TRAIL-R1, TRAIL-R2, TRAIL-R4 and nuclear caspase-8 correlate with the grade of malignancy of HCCs

To analyse the expression level of important regulators of TRAIL-induced apoptosis, tumor tissues from explanted livers (OLT) and partial liver resections (PR) were used in a tissue microarray (cohort A, Table 1, n = 157).

The death-inducing receptors TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 were differentially expressed in normal liver versus HCC. TRAIL-R1 showed strong cytoplasmic staining in normal liver tissue with a mild downregulation in G1 and G2 tumors but a significant downregulation in G3 tumors compared to normal tissue (p = 0.004), but also compared to G1 (p = 0.01) and G2 (p = 0.003) tumors (Figure 3A). In contrast, TRAIL-R2 was expressed in normal liver tissue and significantly upregulated in G2 (p = 0.002) and G3 (p = 0.001) tumor tissue compared to normal tissue (Figure 3B). TRAIL-R2 expression did not significantly differ between G2 and G3 (p = 0.69) or between G1 and G3 (p = 0.07) tumors. TRAIL-R3 showed only low expression, both in normal liver tissue and tumor tissue, which did not correlate with tumor grade (data not shown). TRAIL-R4 was moderately expressed in normal liver tissue and significantly upregulated in G2 (p = 0.032) and G3 (p = 0.0003) tumors (Figure 3C). TRAIL-R4 expression in G3 tumors also significantly differed from G1 (p < 0.001) and G2 (p = 0.012) tumors. Caspase-8 showed only a low level expression in the cytoplasm of normal hepatocytes (Figure 2A), which did not significantly differ from cytosolic expression of caspase-8 in HCCs (Figure 3D). Although in normal liver tissue caspase-8 could not be detected in the nucleus, many HCC samples showed nuclear expression of caspase-8 (Figure 2). Nuclear caspase-8 was significantly higher expressed in G1 (p = 0.016), G2 (p < 0.0001), and G3 (p < 0.0001) HCCs compared to normal liver tissue (Figure 3E). G3 tumors also demonstrated a significantly higher expression of nuclear caspase-8 compared to G1 (p = 0.001) but not compared to G2 (p = 0.06) HCC tissues.

Protein expression levels and WHO grade of malignancies. Expression of TRAIL-R1 (A), TRAIL-R2 (B), TRAIL-R4 (C), cytosolic caspase-8 (D), and nuclear caspase-8 (E) expression in HCC specimens according to tumor grading compared to normal liver tissue. Statistical analysis was performed by the Wilcoxon test. Statistical significance is indicated for all tumor grades in comparison to healthy liver controls.

Cytosolic and nuclear caspase-8 expression levels correlate with survival after partial liver resection

The correlation between survival and protein expression was analysed in n = 49 HCC patients undergoing partial liver resection, for whom survival data were available (Table 1, Cohort B). The correlation between TRAIL-receptor and caspase-8 expression levels and tumor grade showed identical levels of significance in this smaller subgroup.

Neither TRAIL-R1, TRAIL-R2 nor TRAIL-R4 expression scores correlated with patient survival (Figure 4A-C). However, high cytosolic caspase-8 expression in tumor tissue (IRS ≥2.8) significantly correlated with better survival (Figure 4D). Multivariate Cox regression analysis confirmed cytosolic caspase-8 to be a survival predictor independent from tumor grading [G3 versus G1/2: HR = 2.28 (95% CI: 1.14-4.55), p = 0.0196 and cytosolic caspase-8 <2.8 versus ≥2.8: HR = 2.39 (95% CI: 1.16-4.92), p = 0.0182]. In contrast, high nuclear expression of caspase-8 (IRS >10.3) was associated with shorter survival rates in patients after partial liver resection (Figure 4E). Because of the strong correlation of nuclear expression of caspase-8 and tumor grading and the low number of patients with nuclear caspase-8 IRS ≥10.3, none of the two factors were significantly associated with survival in a multivariate Cox regression analysis [G3 vs G1/2: HR = 1.72 (95% CI: 0.85-3.49, p = 0.134 and nuclear caspase-8 ≥10.3 versus <10.3: HR = 1.80 (95% CI: 0.81-4.01)].

Protein levels and patient’s survival rates. Overall survival after partial resection for HCC (n = 49) according to expression of TRAIL-R1 (A), TRAIL-R2 (B), TRAIL-R4 (C), cytosolic caspase-8 (D), and nuclear caspase-8 (E) was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier estimate. Thresholds for high and low protein expression are given for each protein.

Discussion

In this study we assessed the expression of TRAIL receptors, caspase-8, Bcl-xL and Mcl-1 in 157 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and normal liver tissue using tissue microarrays, and correlated the expression with clinico-pathological parameters. Survival analysis was carried out for patients who underwent liver resection.

TRAIL-R1 was significantly downregulated in less differentiated HCC. However, TRAIL-R1 expression did not correlate with patient survival after liver resection. Kriegl et al. reported a significant membrane staining of TRAIL-R1 in HCC compared to normal liver tissue and a longer survival of HCC patients undergoing partial hepatectomy with TRAIL-R1 membrane positive versus negative tumors [31]. However, our immunohistochemical analysis detected considerable cytoplasmic but not membrane TRAIL-R1 staining [31, 37]. Having established the specificity of our TRAIL-R1 (and TRAIL-R2) antibodies in TRAIL-R1- (and TRAIL-R2-) transfected cells, cytoplasmic staining prevailed also in this setting [22]. Using the highly specific antibodies for TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2, HCC cell lines also displayed strong cytoplasmic, rather than membrane, staining which was confirmed by flow cytometry (data not shown). Upon TRAIL death receptor upregulation by chemotherapeutic drugs, membrane staining of both receptors could be detected in HCC cell lines which was paralleled by enhanced surface receptor as detected by flow cytometry [10]. These control experiments support the sensitivity and high specificity of our TRAIL receptor antibodies for both cytoplasmic and membrane staining. Our data are in line with reports on strong cytoplasmic rather than membrane staining of both TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 in primary HCC tissue [33]. Correlation analyses of TRAIL-R1 expression and survival in other tumor entities revealed contradictory results. In colorectal cancer both low [38] and high [39] TRAIL-R1 expression correlated with poorer survival. Ullenhag et al. found no correlation between TRAIL-R1 expression level and survival in colorectal cancer patients [23].

In our study both TRAIL-R2 and TRAIL-R4 were upregulated in dedifferentiated HCCs. However, for none of the TRAIL receptors expression correlated with patient survival. In previous studies high expression of TRAIL-2 [40] was also associated with less differentiated tumors and implied poorer survival in breast cancer [22, 41], renal cell carcinoma [21], and NSCLC [40]. In the report by Kriegl et al., TRAIL-R2 membrane staining correlated with better survival of HCC patients after partial liver resection [31]. However, as stated above, in our cohort no relevant TRAIL-R2 membrane staining could be detected in HCC tissues. In summary, TRAIL receptor expression patterns seem to vary between different tumor entities and, therefore, their correlation with survival data may depend on tumor type and clinical setting (adjuvant, curative and palliative treatment).

Downregulation of TRAIL-R2 in vivo may mirror the selection pressure by antitumor immune responses (e.g. by TRAIL-expressing NK cells). On the other hand, TRAIL-R2-positive tumor cells may have developed TRAIL resistance downstream of the receptor level, thereby allowing for tumor cell proliferation despite TRAIL death receptor expression. Nevertheless, many chemotherapeutic drugs sensitize resistant tumor cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis via enhancement of proapoptotic regulators of the extrinsic and intrinsic pathway [8, 10, 42]. Thus, HCCs with high TRAIL-R2 expression should be eligible for combinatorial TRAIL-based therapies. Previously, we could show that TRAIL-R2 expression was highly correlated with TRAIL-R4 positivity in breast cancer [22]. TRAIL-R4 overexpression correlated with poorer survival in breast [22] and prostate cancer [43]. Applying TRAIL-R2-specific agonists (e.g. the TRAIL-R2-specific antibody lexatumumab) may bypass the anti-apoptotic effects of high TRAIL-R4 expression and allow for effective tumor treatment [11]. It has been discussed that therapeutic implications of TRAIL-based therapies might be limited by toxicity to non-transformed human hepatocytes [44, 45]. Yet, we previously showed that there is a large therapeutic window which allows effective TRAIL-based cancer therapy [10].

Analysis of the two anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members Bcl-xL and Mcl-1 revealed low expression of Bcl-xL in normal liver tissue, which was not-significantly upregulated in G2 and G3 tumors (data not shown). Expression of Mcl-1 was also increased in G3 tumors as compared to G1/2 tumors and normal tissue; however no correlation with survival could be detected (data not shown).

As the main initiator caspase of the TRAIL pathway, caspase-8 is located in the cytosol to be recruited to the TRAIL DISC after ligand binding to TRAIL-R1/R2. Loss or downregulation of caspase-8 has been proposed as a possible mechanism of apoptosis resistance in tumor cells [46]. In our cohort, high cytosolic caspase-8 expression correlated with better survival independently from tumor grade, possibly reflecting the higher apoptotic potential of these tumor cells. Interestingly, we could demonstrate nuclear staining of caspase-8 in HCCs but not in normal hepatocytes. The staining intensity of nuclear caspase-8 correlated with grade of malignancy but also with poorer patient survival. Due to the strong correlation between nuclear expression of caspase-8 and tumor grading, multivariate Cox regression analysis could not detect an influence of nuclear caspase-8 on survival independent from the tumor grade. However, patient number with a nuclear caspase-8 score ≥10.3 might be too small (n = 10) for a multivariate analysis of the two parameters, high nuclear caspase-8 and tumor grading. Thus, our data need to be scrutinized in a larger cohort. Although high nuclear and cytosolic caspase-8 expression have an opposed effect on patient survival, high nuclear and cytoplasmic caspase-8 expression is not mutually exclusive, since 9 out of 56 patients (16%) and 3 out of 14 patients (21%) with a high nuclear caspase-8 score of ≥7 and ≥10.3, respectively, had also an equally high cytoplasmic caspase-8 expression level. Most of these patients had WHO grade 3 tumors (78% for a score ≥7, 100% for a score of ≥10).

Whereas the role of cytosolic caspase-8 as a factor in triggering apoptosis via death receptors has been well examined [24, 47, 48], nuclear translocation of caspase-8 has so far not been described in HCCs. In contrast, nuclear localisation of caspase-8 has been found in apoptotic neurons [49]. Since these cells were undergoing apoptosis, caspase-8 was suspected to shuttle to the nucleus to exert cleavage of the DNA repair enzyme PARP2, a hallmark of apoptotic cell death. In contrast to apoptotic neurons, in our study nuclear caspase-8 was detected in nearly all tumor cells of poorly differentiated HCCs (Figures 2 and 3E) and nuclear caspase-8 expression did not correlate with the apoptosis rate (r = 0.078, p = 0.420). This may indicate a non-apoptotic function of caspase-8 in HCCs. Enhancement of tumor cell migration and inhibition of Fas-induced apoptosis has been recently described as a non-apoptotic function of caspase-8 in different experimental cancer cell lines, which was not dependent on its catalytic activity but on Src-mediated phosphorylation of Tyr380 in a linker region between the small and large caspase-8 subunits [50, 51]. Metastasis formation of non-apoptotic neuroblastoma cells was enhanced by recruitment of caspase-8 to the cellular migration machinery [52]. Interestingly, in our cohort, high nuclear expression of caspase-8 correlated with a higher proliferation index of tumor cells (Ki67, r = 0.282, p = 0.0004, whereas the cytosolic expression of caspase-8 did not (r = 0.089, p = 0.274). A recent study has shown that caspase-8 can be sumoylated at lysine 156 leading to a 75 kDa isoform (p75) and that sumoylation of caspase-8 by SUMO-1 is associated with nuclear localization of caspase-8 [53] suggesting that nuclear expression of caspase-8 in our study might be a result of sumoylation. Interestingly, SUMO-1 is overexpressed in HCCs [54] and expression profiling has shown that HCC patients with shorter survival show higher expression of genes involved in sumoylation [55, 56]. Although the physiological relevance of sumoylated caspase-8 is unclear, recent studies suggest that sumoylation of caspase-8 does not impair cytoplasmic caspase-8 activation, but that sumoylated nuclear caspase-8 (p75) can presumably cleave other, so far undefined, specific nuclear substrates [53]. However, using a cleavage-specific antibody for caspase-8, we could not detect activated caspase-8 in the nuclei of tumor cells in our cohort.

Conclusions

In conclusion, differential expression of TRAIL-R1, TRAIL-R2 and TRAIL-R4 may help to histopathologically identify hepatocellular carcinoma patients who could benefit from TRAIL-based therapies. Prospective studies are needed to confirm the predictive role of TRAIL-receptor expression patterns for TRAIL-based therapies or TRAIL-dependent mechanisms of other chemotherapeutic drugs. Furthermore, the prognostic role of nuclear localisation of caspase-8 needs to be confirmed in larger trials and other tumor entities. Identifying the molecular targets and pathophysiological consequences of nuclear caspase-8 may reveal novel, non-apoptotic functions of this crucial initiator caspase.

Abbreviations

- Bcl-xL:

-

B-cell lymphoma-extra large

- DR:

-

Death receptor

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- Mcl-1:

-

Induced myeloid leukemia cell differentiation protein

- mIgG:

-

Mouse IgG

- NF-κB:

-

Nuclear factor kappa B

- OLT:

-

Orthotopic liver transplantation

- PLAD:

-

Preligand assembly domain

- SUMO:

-

Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- TRAIL:

-

TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand

- TRAIL-R1:

-

TRAIL-receptor 1

- TRAIL-R2:

-

TRAIL-receptor 2

- TRAIL-R3:

-

TRAIL-receptor 3

- TRAIL-R4:

-

TRAIL-receptor 4.

References

Venook AP, Papandreou C, Furuse J, de Guevara LL: The incidence and epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: a global and regional perspective. Oncologist. 2010, 15 (Suppl 4): 5-13.

Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P: Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005, 55 (2): 74-108. 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74.

Breuhahn K, Gores G, Schirmacher P: Strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy and diagnostics: lessons learned from high throughput and profiling approaches. Hepatology. 2011, 53 (6): 2112-2121. 10.1002/hep.24313.

Koschny R, Schmidt J, Ganten TM: Beyond Milan criteria–chances and risks of expanding transplantation criteria for HCC patients with liver cirrhosis. Clin Transplant. 2009, 23 (Suppl 21): 49-60.

Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A, et al: Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008, 359 (4): 378-390. 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857.

Wiley SR, Schooley K, Smolak PJ, Din WS, Huang CP, Nicholl JK, Sutherland GR, Smith TD, Rauch C, Smith CA, et al: Identification and characterization of a new member of the TNF family that induces apoptosis. Immunity. 1995, 3 (6): 673-682. 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90057-8.

Pitti RM, Marsters SA, Ruppert S, Donahue CJ, Moore A, Ashkenazi A: Induction of apoptosis by Apo-2 ligand, a new member of the tumor necrosis factor cytokine family. J Biol Chem. 1996, 271 (22): 12687-12690. 10.1074/jbc.271.22.12687.

Ganten TM, Koschny R, Haas TL, Sykora J, Li-Weber M, Herzer K, Walczak H: Proteasome inhibition sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma cells, but not human hepatocytes, to TRAIL. Hepatology. 2005, 42 (3): 588-597. 10.1002/hep.20807.

Ganten TM, Koschny R, Sykora J, Schulze-Bergkamen H, Buchler P, Haas TL, Schader MB, Untergasser A, Stremmel W, Walczak H: Preclinical differentiation between apparently safe and potentially hepatotoxic applications of TRAIL either alone or in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs. Clin Cancer Res. 2006, 12 (8): 2640-2646. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2635.

Koschny R, Ganten TM, Sykora J, Haas TL, Sprick MR, Kolb A, Stremmel W, Walczak H: TRAIL/bortezomib cotreatment is potentially hepatotoxic but induces cancer-specific apoptosis within a therapeutic window. Hepatology. 2007, 45 (3): 649-658. 10.1002/hep.21555.

Koschny R, Walczak H, Ganten TM: The promise of TRAIL-potential and risks of a novel anticancer therapy. J Mol Med. 2007, 85 (9): 923-935. 10.1007/s00109-007-0194-1.

Pan G, O’Rourke K, Chinnaiyan AM, Gentz R, Ebner R, Ni J, Dixit VM: The receptor for the cytotoxic ligand TRAIL. Science. 1997, 276 (5309): 111-113. 10.1126/science.276.5309.111.

Walczak H, Degli-Esposti MA, Johnson RS, Smolak PJ, Waugh JY, Boiani N, Timour MS, Gerhart MJ, Schooley KA, Smith CA, et al: TRAIL-R2: a novel apoptosis-mediating receptor for TRAIL. Embo J. 1997, 16 (17): 5386-5397. 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5386.

Sheridan JP, Marsters SA, Pitti RM, Gurney A, Skubatch M, Baldwin D, Ramakrishnan L, Gray CL, Baker K, Wood WI, et al: Control of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by a family of signaling and decoy receptors. Science. 1997, 277 (5327): 818-821. 10.1126/science.277.5327.818.

Pan G, Ni J, Wei YF, Yu G, Gentz R, Dixit VM: An antagonist decoy receptor and a death domain-containing receptor for TRAIL. Science. 1997, 277 (5327): 815-818. 10.1126/science.277.5327.815.

Mongkolsapaya J, Cowper AE, Xu XN, Morris G, McMichael AJ, Bell JI, Screaton GR: Lymphocyte inhibitor of TRAIL (TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand): a new receptor protecting lymphocytes from the death ligand TRAIL. J Immunol. 1998, 160 (1): 3-6.

Degli-Esposti MA, Dougall WC, Smolak PJ, Waugh JY, Smith CA, Goodwin RG: The novel receptor TRAIL-R4 induces NF-kappaB and protects against TRAIL-mediated apoptosis, yet retains an incomplete death domain. Immunity. 1997, 7 (6): 813-820. 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80399-4.

Clancy L, Mruk K, Archer K, Woelfel M, Mongkolsapaya J, Screaton G, Lenardo MJ, Chan FK: Preligand assembly domain-mediated ligand-independent association between TRAIL receptor 4 (TR4) and TR2 regulates TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005, 102 (50): 18099-18104. 10.1073/pnas.0507329102.

Simonet WS, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, Kelley M, Chang MS, Luthy R, Nguyen HQ, Wooden S, Bennett L, Boone T, et al: Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density [see comments]. Cell. 1997, 89 (2): 309-319. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80209-3.

Falschlehner C, Emmerich CH, Gerlach B, Walczak H: TRAIL signalling: Decisions between life and death. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007, 39 (7-8): 1462-1475. 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.02.007.

Macher-Goeppinger S, Aulmann S, Tagscherer KE, Wagener N, Haferkamp A, Penzel R, Brauckhoff A, Hohenfellner M, Sykora J, Walczak H, et al: Prognostic value of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) and TRAIL receptors in renal cell cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009, 15 (2): 650-659. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0284.

Ganten TM, Sykora J, Koschny R, Batke E, Aulmann S, Mansmann U, Stremmel W, Sinn HP, Walczak H: Prognostic significance of tumour necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) receptor expression in patients with breast cancer. J Mol Med. 2009, 87 (10): 995-1007. 10.1007/s00109-009-0510-z.

Ullenhag GJ, Mukherjee A, Watson NF, Al-Attar AH, Scholefield JH, Durrant LG: Overexpression of FLIPL is an independent marker of poor prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2007, 13 (17): 5070-5075. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2547.

Kantari C, Walczak H: Caspase-8 and bid: caught in the act between death receptors and mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011, 1813 (4): 558-563. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.01.026.

Tibbetts MD, Zheng L, Lenardo MJ: The death effector domain protein family: regulators of cellular homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2003, 4 (5): 404-409. 10.1038/ni0503-404.

Kang MH, Reynolds CP: Bcl-2 inhibitors: targeting mitochondrial apoptotic pathways in cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009, 15 (4): 1126-1132. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0144.

Hikita H, Takehara T, Shimizu S, Kodama T, Shigekawa M, Iwase K, Hosui A, Miyagi T, Tatsumi T, Ishida H, et al: The Bcl-xL inhibitor, ABT-737, efficiently induces apoptosis and suppresses growth of hepatoma cells in combination with sorafenib. Hepatology. 2010, 52 (4): 1310-1321. 10.1002/hep.23836.

Sieghart W, Losert D, Strommer S, Cejka D, Schmid K, Rasoul-Rockenschaub S, Bodingbauer M, Crevenna R, Monia BP, Peck-Radosavljevic M, et al: Mcl-1 overexpression in hepatocellular carcinoma: a potential target for antisense therapy. J Hepatol. 2006, 44 (1): 151-157. 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.09.010.

Weber A, Boger R, Vick B, Urbanik T, Haybaeck J, Zoller S, Teufel A, Krammer PH, Opferman JT, Galle PR, et al: Hepatocyte-specific deletion of the antiapoptotic protein myeloid cell leukemia-1 triggers proliferation and hepatocarcinogenesis in mice. Hepatology. 2010, 51 (4): 1226-1236. 10.1002/hep.23479.

Fabregat I: Dysregulation of apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2009, 15 (5): 513-520. 10.3748/wjg.15.513.

Kriegl L, Jung A, Engel J, Jackstadt R, Gerbes AL, Gallmeier E, Reiche JA, Hermeking H, Rizzani A, Bruns CJ, et al: Expression, cellular distribution, and prognostic relevance of TRAIL receptors in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010, 16 (22): 5529-5538. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3403.

Shiraki K, Yamanaka T, Inoue H, Kawakita T, Enokimura N, Okano H, Sugimoto K, Murata K, Nakano T: Expression of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2005, 26 (5): 1273-1281.

Chen XP, He SQ, Wang HP, Zhao YZ, Zhang WG: Expression of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing Ligand receptors and antitumor tumor effects of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing Ligand in human hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2003, 9 (11): 2433-2440.

Herr I, Schemmer P, Buchler MW: On the TRAIL to therapeutic intervention in liver disease. Hepatology. 2007, 46 (1): 266-274. 10.1002/hep.21740.

Nzeako UC, Goodman ZD, Ishak KG: Comparison of tumor pathology with duration of survival of North American patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 1995, 76 (4): 579-588. 10.1002/1097-0142(19950815)76:4<579::AID-CNCR2820760407>3.0.CO;2-D.

Zhuang L, Lee CS, Scolyer RA, McCarthy SW, Zhang XD, Thompson JF, Hersey P: Mcl-1, Bcl-XL and Stat3 expression are associated with progression of melanoma whereas Bcl-2, AP-2 and MITF levels decrease during progression of melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2007, 20 (4): 416-426. 10.1038/modpathol.3800750.

Zhang Y, Zhang B: TRAIL resistance of breast cancer cells is associated with constitutive endocytosis of death receptors 4 and 5. Mol Cancer Res. 2008, 6 (12): 1861-1871. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0313.

Granci V, Bibeau F, Kramar A, Boissiere-Michot F, Thezenas S, Thirion A, Gongora C, Martineau P, Del Rio M, Ychou M: Prognostic significance of TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R3 expression in metastatic colorectal carcinomas. Eur J Cancer. 2008, 44 (15): 2312-2318. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.06.042.

Strater J, Hinz U, Walczak H, Mechtersheimer G, Koretz K, Herfarth C, Moller P, Lehnert T: Expression of TRAIL and TRAIL Receptors in Colon Carcinoma: TRAIL-R1 Is an Independent Prognostic Parameter. Clin Cancer Res. 2002, 8 (12): 3734-3740.

Spierings DC, de Vries EG, Timens W, Groen HJ, Boezen HM, de Jong S: Expression of TRAIL and TRAIL death receptors in stage III non-small cell lung cancer tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2003, 9 (9): 3397-3405.

McCarthy MM, Sznol M, DiVito KA, Camp RL, Rimm DL, Kluger HM: Evaluating the expression and prognostic value of TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005, 11 (14): 5188-5194. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0158.

Ganten TM, Haas TL, Sykora J, Stahl H, Sprick MR, Fas SC, Krueger A, Weigand MA, Grosse-Wilde A, Stremmel W, et al: Enhanced caspase-8 recruitment to and activation at the DISC is critical for sensitisation of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis by chemotherapeutic drugs. Cell Death Differ. 2004, 11 (Suppl 1): S86-S96.

Koksal IT, Sanlioglu AD, Karacay B, Griffith TS, Sanlioglu S: Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand-R4 decoy receptor expression is correlated with high Gleason scores, prostate-specific antigen recurrence, and decreased survival in patients with prostate carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2008, 26 (2): 158-165. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.01.022.

Jo M, Kim TH, Seol DW, Esplen JE, Dorko K, Billiar TR, Strom SC: Apoptosis induced in normal human hepatocytes by tumor necrosis factor- related apoptosis-inducing ligand. Nat Med. 2000, 6 (5): 564-567. 10.1038/75045.

Lawrence D, Shahrokh Z, Marsters S, Achilles K, Shih D, Mounho B, Hillan K, Totpal K, DeForge L, Schow P, et al: Differential hepatocyte toxicity of recombinant Apo2L/TRAIL versions. Nat Med. 2001, 7 (4): 383-385. 10.1038/86397.

Grotzer MA, Eggert A, Zuzak TJ, Janss AJ, Marwaha S, Wiewrodt BR, Ikegaki N, Brodeur GM, Phillips PC: Resistance to TRAIL-induced apoptosis in primitive neuroectodermal brain tumor cells correlates with a loss of caspase-8 expression. Oncogene. 2000, 19 (40): 4604-4610. 10.1038/sj.onc.1203816.

Muzio M, Chinnaiyan AM, Kischkel FC, O’Rourke K, Shevchenko A, Ni J, Scaffidi C, Bretz JD, Zhang M, Gentz R, et al: FLICE, a novel FADD-homologous ICE/CED-3-like protease, is recruited to the CD95 (Fas/APO-1) death–inducing signaling complex. Cell. 1996, 85 (6): 817-827. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81266-0.

Boldin MP, Goncharov TM, Goltsev YV, Wallach D: Involvement of MACH, a novel MORT1/FADD-interacting protease, in Fas/APO-1- and TNF receptor-induced cell death. Cell. 1996, 85 (6): 803-815. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81265-9.

Benchoua A, Couriaud C, Guegan C, Tartier L, Couvert P, Friocourt G, Chelly J, Menissier-de Murcia J, Onteniente B: Active caspase-8 translocates into the nucleus of apoptotic cells to inactivate poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-2. J Biol Chem. 2002, 277 (37): 34217-34222. 10.1074/jbc.M203941200.

Cursi S, Rufini A, Stagni V, Condo I, Matafora V, Bachi A, Bonifazi AP, Coppola L, Superti-Furga G, Testi R, et al: Src kinase phosphorylates Caspase-8 on Tyr380: a novel mechanism of apoptosis suppression. EMBO J. 2006, 25 (9): 1895-1905. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601085.

Barbero S, Barila D, Mielgo A, Stagni V, Clair K, Stupack D: Identification of a critical tyrosine residue in caspase 8 that promotes cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2008, 283 (19): 13031-13034. 10.1074/jbc.M800549200.

Barbero S, Mielgo A, Torres V, Teitz T, Shields DJ, Mikolon D, Bogyo M, Barila D, Lahti JM, Schlaepfer D, et al: Caspase-8 association with the focal adhesion complex promotes tumor cell migration and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2009, 69 (9): 3755-3763. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3937.

Besnault-Mascard L, Leprince C, Auffredou MT, Meunier B, Bourgeade MF, Camonis J, Lorenzo HK, Vazquez A: Caspase-8 sumoylation is associated with nuclear localization. Oncogene. 2005, 24 (20): 3268-3273. 10.1038/sj.onc.1208448.

Guo WH, Yuan LH, Xiao ZH, Liu D, Zhang JX: Overexpression of SUMO-1 in hepatocellular carcinoma: a latent target for diagnosis and therapy of hepatoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011, 137 (3): 533-541. 10.1007/s00432-010-0920-x.

Jain S, Singhal S, Lee P, Xu R: Molecular genetics of hepatocellular neoplasia. Am J Transl Res. 2010, 2 (1): 105-118.

Lee JS, Thorgeirsson SS: Genome-scale profiling of gene expression in hepatocellular carcinoma: classification, survival prediction, and identification of therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology. 2004, 127 (5 Suppl 1): S51-S55.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/13/532/prepub

Acknowledgments

We thank Jutta Mohr for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported, in part, by a programme grant from Cancer Research UK to HW and by the DFG to RK and TMG.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SB and RK participated in the design of the study and wrote the manuscript together with TMG. JS established the staining protocols for all antibodies and carried out the immunohistochemical studies together with SB and EB. EB collected clinical data. UH performed the statistical analysis. PS participated in the design and coordination of the study. WS conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. PS, SS and KB provided the histoarrays and revised the manuscript. HW developed all TRAIL-receptor-specific antibodies employed in this study, oversaw the establishing of the staining protocols for all antibodies, initiated and designed the study together with TMG, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ronald Koschny, Sylvia Brost contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Koschny, R., Brost, S., Hinz, U. et al. Cytosolic and nuclear caspase-8 have opposite impact on survival after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer 13, 532 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-13-532

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-13-532