Abstract

Around 1.3 billion tonnes of food are wasted worldwide per year, which is originally produced under extensive use of energy and nutrients. Use of food waste as feedstock in biotechnological processes provides an innovative way to recover parts of the energy and nutrients initially spent on food production. By chemical and biological methods, food waste is hydrolysed to glucose, free amino nitrogen and phosphate, which are utilisable as nutrients by many microorganisms whose metabolic versatility enables the production of a wide range of products. Microalgae are particularly of interest as chemicals, materials and energy are obtainable from microalgal biomass after chemical and/or biological modifications. In this review, valorisation of food waste in biotechnological processes is presented as an additional option to green chemical technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

One third of the food produced globally for human consumption is wasted yearly [1, 2]. Japan, China and Republic of Korea, summarised as industrialised Asia in Table 1, produce annually 357 million tonnes of food waste. It is followed by South & Southeast Asia (275 million tonnes) and Europe (205 million tonnes). In Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, North America and Oceania, North Africa and Western & Central Asia, 100 million to 130 million tonnes of food are wasted per year, respectively. The overall amount of food wasted and lost worldwide corresponds to around 1.3 billion tonnes. This amount includes all kinds of food, such as cereals, roots and tubers, oilseed and pulses, fruits and vegetables, meat, seafood, milk and eggs [1, 2].

A study of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations revealed that food is lost and wasted at all production processes from agricultural production to consumer levels [1]. Regardless where food is wasted or lost, it is either disposed in landfill sites or otherwise treated in order to prevent environmental problems. Particularly in densely populated areas, food waste can cause serious health problems and requires a proper treatment.

Elimination of food waste by dumping into landfill sites is inappropriate, as the production of food is energy and nutrient demanding [3, 4]. Many studies have been carried out which describe the possibilities to produce energy from food waste by incineration and anaerobic digestion, or to use food waste as feed for pigs and cattle in order to close the nutrient loop [5–11]. Another approach is the application of food waste as feedstock in cultivation of microorganisms. This approach allows the recycling of waste matters consisting of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous compounds, by assimilation in biomass and metabolites of microorganisms, being used for production of chemicals, materials and energy.

This review presents an overview of utilisation of food waste as feedstock in biotechnological processes, with focus on microalgae cultivation, as an additional option to valorisation by green chemical technologies [12].

The term “food waste” describes industrial, commercial and domestic mixed food residues, bread and other bakery wastes meant for human consumption. Contrarily, the term “organic waste” describes those waste matters (e.g. peels and rapeseed meal) not meant for human consumption. The term “biomass” describes all biological materials, but not food and organic wastes, while “microalgal biomass” refers to microalgae-derived biomass.

Organic and food wastes as raw materials

Recycling of organic wastes by chemical modification and production of chemicals is one option to overcome the challenges of resource depletion [13]. Another option is the recovery of sugar monomers, glycerol, short and long fatty acids, amino acids and phosphate from food waste, which are wanted nutrients in many biotechnological processes for cultivation of bacteria, fungi, algae, and production of primary and secondary metabolites [14–20].

Recovery of nutrients from food and organic wastes

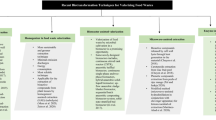

A composition of 30–60% starch, 5–10% proteins and 10–40% (w/w) lipids makes food waste to a promising raw material [5, 14, 15]. Recovery of nutrients from food waste in the form of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous compounds can be performed by chemical and biological/enzymatic methods after solubilisation of the waste matter [21–25].

Food waste is a mixture of different kinds of food residues e.g. bread, pastry, noodles, rice, potato, meat and vegetables [1, 2]. Therefore, in order to hydrolyse most of the waste matters, a consortium of hydrolytic enzymes (e.g. glucoamylases, cellulases, proteases and phosphatases) is needed. Kim et al. used an enzyme mixture consisting of carbohydrase, glucoamylase, cellulase and protease to hydrolyse food waste and obtained 0.63 g glucose g-1 total solids applied [21]. Yan et al. used fungal α-amylase and glucoamylase for hydrolysis of food waste and reached an almost complete digestion of starch in a fed-batch process [22]. Claassen et al. used a different approach and treated domestic organic waste first by Masonite steam explosion at 200°C for 6 minutes to increase the solubility of waste matters, followed by a treatment of the liquid and remaining solids with commercial cellulolytic enzymes [23].

On the contrary, chemical hydrolysis carried out under acidic or alkaline conditions and heat has the advantage that the waste matter is solubilised to a greater extent than under mild conditions [17, 20, 24]. However, the resultant hydrolysate containing the recovered nutrients is strongly acidic or alkaline, and it requires neutralisation prior to the use as nutrient source for most microorganisms [20]. Additionally, in order to use hydrolysate as nutrient source, it is essential to convert the waste matter into compounds like glucose, acetic acid, amino acids and phosphate that can be taken up and assimilated by microorganisms. This prerequisite excludes oxidative treatments e.g. by H2O2 in supercritical water resulting in further oxidation of released glucose [26].

The application of commercial enzymes for hydrolysis of food and organic wastes may require the recovery and reuse of enzymes to make the overall process cost-efficient. In order to reduce process costs, degradation of food wastes was performed in situ by Aspergillus awamori and Aspergillus oryzae, which are well-known fungal secretors of glucoamylase, protease and phosphatase [14, 15, 18, 27]. Similar processes have been previously investigated for the utilisation of wheat and rapeseed meal for the recovery of glucose, free amino nitrogen and phosphate [28–30]. It has been shown that the secretion of hydrolytic enzymes by A. awamori and A. oryzae is sufficient to degrade most of the starch, proteins and polyphosphates in food waste [14, 15, 18].

A different approach to recover nutrients from food and organic wastes was used by Fan et al. [31]. Dried and blended bread crusts, okara powder and brewing grain were directly added to shake flasks containing the thraustochytrid Schizochytrium mangrovei KF6. The results revealed that S. mangrovei grows on a medium containing bread waste particles and accumulates the high-value polyunsaturated fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid. This study illustrates the simplicity of using food and organic wastes as nutrient sources in cultivation of microorganisms [31].

Food waste as nutrient source in heterotrophic microalgae cultivation

Heterotrophic microalgae can be grown at high biomass concentrations in stirred bioreactor. However, cost-intensive culture media consisting of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous sources are needed [32–35]. The costs of nutrients can be lowered when organic wastes are used as fermentation feedstock and this may also account for the use of food waste [17]. However, despite the staggering amount of food waste produced worldwide (Table 1), only few studies have been reported which focus on the use of food waste as nutrient source in heterotrophic microalgae cultivation.

Pleissner et al. first reported that the algae Chlorella pyrenoidosa and Schizochytrium mangrovei grow on pure food waste hydrolysate, which was obtained after fungal hydrolysis of commercial food residues, without supplements of trace metals and vitamins [15]. The hydrolysate consisted of glucose, free amino nitrogen, phosphate and most likely long chain fatty acids. S. mangrovei grew twice as fast on hydrolysate supplemented with 15 g L-1 artificial sea salt as compared to cells exposed to a defined medium. The growth rate of C. pyrenoidosa in hydrolysate, however, was reduced by 50% as compared to growth on a defined medium [15]. Nevertheless, the fact that pure food waste hydrolysate is sufficient to culture fresh water algal strains, and only sea salt is needed as supplement for marine species indicates that food waste may be a promising nutrient source for many algal strains.

An economic evaluation of microalgae cultivation processes based on food waste is currently on-going in our laboratory, the broad range of chemicals and polymers obtainable from microalgal biomass, however, may make it economically feasible [36].

Microalgal biomass and food waste as feedstocks

The synthesis of chemicals mainly bases on petroleum known to be depleted in the not-too-distant future. Therefore, research activities are focused on substitution of petroleum by sustainable feedstocks (e.g. biomass) for the synthesis of chemicals [37].

Increasing interest in biomass as feedstock in chemical production results in increased cultivation of energy-rich non-editable plants over edible plants. Also, it triggered an ethical debate which relates to whether the production of chemicals and energy should have priority over food and feed. An opportunity to overcome the occupation of arable land by non-edible plants is utilising food and organic waste streams and microalgal biomass. In fact, microalgae being cultivated in bioreactors or open ponds do not compete for arable land.

Carbohydrates, proteins, lipids and fatty acids present in microalgal biomass are of significant importance, as these compounds can serve as raw materials in chemical production [36]. Until now, there is little public acceptance of products, particularly food and food supplements directly obtained from food waste. Microalgae cultivation on food waste, therefore, can be considered as a sanitation step to change from “no value waste” to a “valuable raw material”, which is even useable as food and feed. Additionally, the composition of microalgal biomass is controllable by certain nutrient limitation towards high carbohydrate, lipid and polyunsaturated fatty acid or protein contents and leads to higher yields of the desired compound [35].

Table 2 gives a brief overview of chemicals producible from microalgal biomass and food waste. Fatty acids are chemically convertible into plasticiser and polyurethane dispersion, and starch into polyols [38–41]. Starch and proteins are hydrolysable and useable as feedstocks for microbial production of organic acids and polyhydroxyalkanoates [18, 28, 29, 42, 43].

Deshpande and Daniels [44] investigated the lipolytic yeast Candida bombicola for production of sophorolipids, a group of glycolipid bio-surfactants. After 68 hours of fermentation time a sophorolipid concentration of 120 g L-1 was obtained on a complex medium containing animal fat and glucose as carbon sources at pH 3.4 and 27°C. This approach is particularly interesting as other carbon sources e.g. sunflower, safflower and canola oils, but also oils from food waste are utilisable as precursor in sophorolipid production [44, 45].

Compounds directly obtainable from microalgal biomass are ascorbic acid and pigments like xanthophylls and phycobiliproteins [46–48].

In nature, pigments are required for capturing the energy of sunlight to power photosynthesis. Even though heterotrophic microalgae are not depending on sunlight as energy source, certain strains such as Chlorella pyrenoidosa, Chlorella protothecoides and Galdieria sulphuraria synthesise pigments [47–49].

The green alga Chlorella pyrenoidosa can be grown heterophically and has been investigated for the production of xanthophylls (lutein, zeaxanthin, violaxanthin and neoxanthin) used by food industry to color skins of meat and egg yolk. In continuous cultures of C. pyrenoidosa, 302 g L-1 of biomass and a total xanthophylls concentration of 0.65 g L-1 were obtained [47]. Another study describes the production of lutein by Chlorella protothecoides in nitrogen sufficient and limited fed-batch cultures, with glucose as main carbon source [48]. In both fed-batch cultures, around 50 g L-1 of biomass and 0.2 g L-1 of lutein were produced.

Phycocyanin, a blue appearing phycobiliprotein with applications as fluorescent probe, food additive and antioxidant has been successfully produced using the rhodophyte Galdieria sulphuraria under heterotrophic conditions [49–53]. Graverhold and Eriksen reported the production of 100 g L-1 G. sulphuraria biomass from which 3 g L-1 phycocyanin were extracted [49].

Even though heterotrophic algae open the pathway to various pigments, large amounts of glucose were needed in the processes mentioned above. In total, 520 g L-1 and 260 g L-1 of glucose were consumed by Chlorella pyrenoidosa and Galdieria sulphuraria to produce 0.65 and 3 g L-1 of xanthophylls and phycocyanin, respectively [47, 49]. Until now, no study has been reported for the growth of G. sulphuraria on food waste hydrolysate. Therefore, it remains speculative if this may be an alternative to glucose. However, C. pyrenoidosa grows on food waste hydrolysate and this can be a cost-efficient substitute for glucose in xanthophylls production [15, 47].

Biodiesel production

Biofuels became one of the most wanted bio-products as the price of petroleum based fuels is continuously rising. In particular biodiesel (fatty acid methyl esters, FAMEs or fatty acid ethyl esters, FAEEs) production from oilseeds and microalgae attracted much attention in recent years. It is known that microalgae grow faster and a higher yield of oil per area can be obtained compared to oilseeds. Additionally, microalgal lipids can form more than 50% (w/w) of the microalgal biomass and depending on the algal species, lipids can be rich in (poly)unsaturated and saturated fatty acids [54, 55].

Biodiesel produced from microalgal biomass has been found to be competitive to conventional diesel fuels in terms of quality [55]. However, it was found that the FAME of the polyunsaturated fatty acid linolenic acid leads to low thermal efficiency and high nitrogen oxides emission [56]. Thus, a high content of saturated fatty acids is preferred.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (e.g. docosahexaenoic and eicosapentaenoic acids) are well known for their health benefits. Therefore, it is recommended to separate saturated fatty acids from unsaturated ones prior to biodiesel production in order to improve the biodiesel quality and to obtain a by-product that can favour the process economy.

Microalgal biomass, however, is not only rich in lipids, but also in carbohydrates and proteins. Therefore, lipid-extracted microalgae debris consists of mainly proteins and carbohydrates, and it is a promising feed source or feedstock [57, 58].

Green chemical technologies contribute to the production of affordable products from biomass under cost-efficient and environmentally benign conditions. Particularly, the production of biodiesel from microalgal biomass is a good example for the importance of an appropriate downstream processing based on the latest developments in green chemistry. In order to produce biodiesel, lipids are extracted and transesterified. The robust cell wall of microalgae, however, makes lipid extraction difficult and a disruptive treatment of algal cells by microwaves or sonication prior to extraction was found to give higher yields of lipids [59, 60].

Conventional lipid extraction methods base on ethyl acetate/methanol and chloroform, followed by acid or base catalysed transesterification with methanol in order to convert fatty acids into biodiesel [60–62]. However, the use of organic solvents for extraction is not only cost-intensive, but it raises concerns about the environmental benignity of biodiesel production. To overcome the use of organic solvents, supercritical carbon dioxide has been investigated and found to be a promising substitute for methanol and chloroform in lipid extraction. Additionally, the energy demanding drying of biomass prior to lipid extraction can be skipped when supercritical carbon dioxide is used [63].

Another approach to minimize energy demand, process steps and use of organic solvents is the direct or in situ transesterification (Table 3), which is the direct treatment of lipid containing biomass for production of biodiesel (FAMEs or FAEEs) by combining extraction and transesterification methods [64]. For example, Patil et al. investigated the direct transesterification of wet microalgae using supercritical methanol and obtained highly purified extracts [65]. In this study, around 80% (w/w) of lipids from Nannochloropsis were extracted and transesterified in 25 minutes at 250°C and 1200 psi. Water from microalgal biomass served as a co-solvent, making the most energy demanding step – drying of biomass unnecessary [65]. Contrarily, a relatively low yield of biodiesel between 56 and 65% (w/w) has been obtained when wet microalgal biomass was treated under microwave assisted conditions with supercritical ethanol [66].

Additionally to chemical methods, transesterification can also be performed by enzymes (Table 3). Tran et al. used an immobilised lipase from Burkholderia and achieved a transesterification of more than 90% (w/w) of the microalgal oil from Chlorella vulgaris after 48 hours [67].

The methods listed in Table 3 may also be suitable for a biodiesel production from food waste, but variable lipid contents in food waste may make it economically unfavourable [5, 14, 15]. However, remaining solids obtained after hydrolysis of food waste by Aspergillus awamori and Aspergillus oryzae were found to be rich in lipids (~80%, w/w) and it is currently under investigation as feedstock for production of biodiesel in our laboratory.

Conclusions

This review reported approaches for the valorisation of food waste in biotechnological processes developed in recent years. The recovery of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous from food waste by chemical and biological methods enables the recycling of valuable nutrients for the production of chemicals, materials and energy. Valorisation of food waste is not only an environmentally benign waste treatment, but it also benefits to the bio-based economy, as pure and expensive nutrient sources can be substituted. The integration of food waste treatment in existing biotechnological processes can shorten the pathway from “no value waste” to “value-added products”. Together with green chemical technologies, it contributes to a sustainable society.

Authors’ information

DP is currently a postdoctoral fellow and CSKL is an Assistant Professor in the School of Energy and Environment at the City University of Hong Kong.

References

Gustavsson J, Cederberg C, Sonesson U, Otterdijk RV, Meybeck A: Global food losses and food waste. Extent, causes and prevention. 2011, Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 38-

Gustavsson J, Cederberg C, Sonesson U, Emanuelsson A: The methodology of the FOA study: global food losses and food waste-extent, causes and prevention. 2013, Gothenburg, Sweden: The Swedish Institute for Food and Biotechnology, 70-

Cuéllar AD, Webber ME: Wasted food, wasted energy: The embedded energy in food waste in the United States. Environ Sci Technol. 2010, 44: 6464-6469.

Zilbermann D, Dale BE, Fixen PE, Havlin JL: Food, fuel, and plant nutrients use in the future. CAST Issue Paper. 2013, 51: 1-24.

Sayeki M, Kitagawa T, Matsumoto M, Nishiyama A, Miyoshi K, Mochizuki M, Takasu A, Abe A: Chemical composition and energy value of dried meal from food waste as feedstuff in swine and cattle. Anim Sci J. 2001, 72: 34-40.

Shin H-S, Youn J-H: Conversion of food waste into hydrogen by thermophilic acidogenesis. Biogeosciences. 2005, 16: 33-44.

Argelier S, Delgenes JP, Moletta R: Design of acidogenic reactors for the anaerobic treatment of the organic fraction of solid food waste. Bioprocess Eng. 1998, 18: 309-315.

Li R, Chen S, Li X: Biogas production from anaerobic co-digestion of food waste with dairy manure in a two-phase digestion system. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2010, 160: 643-654.

Kim S, Choi K, Kim JO, Chung J: Biological hydrogen production by anaerobic digestion of food waste and sewage sludge treated using various pretreatment technologies. Biogeosciences. 2013, 24: 753-764.

Myer RO, Johnson DD, Boswick KK, Brendemuhl JH: Dehydration of restaurant food wastes produces a nutritious feedstuff for use in pig diets. Utilization of Agricultural, Municipal and Industrial By-products. Edited by: Brown S, Angle JS, Jacobs L. 1998, Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publisher, 397-403.

Nelson T: Closing the nutrient loop. 1996, Washington DC, USA: World watch, 10-17.

Luque R, Clark JH: Valorisation of food residues: waste to wealth using green chemical technologies. Sus Chem Proc. 2013, 1: 10-

Pfaltzgraff LA, De Bruyn M, Cooper EC, Budarin V, Clark JH: Food waste biomass: a resource for high-value chemicals. Green Chem. 2013, 15: 307-314.

Zhang AY-Z, Sun Z, Leung CCJ, Han W, Lau KY, Li M, Lin CSK: Valorisation of bakery waste for succinic acid production. Green Chem. 2013, 15: 690-695.

Pleissner D, Lam WC, Sun Z, Lin CSK: Food waste as nutrient source in heterotrophic microalgae cultivation. Biores Technol. 2013, 137: 139-146.

Yan S, Li J, Chen X, Wu J, Wang P, Ye J, Yao J: Enzymatical hydrolysis of food waste and ethanol production from the hydrolysate. Renew Energy. 2011, 36: 1259-1265.

Ryu B-G, Kim K, Kim J, Han J-I, Yang J-W: Use of organic waste from the brewery industry for high-density cultivation of the docosahexaenoic acid-rich microalga, Aurantiochytrium sp. KRS101. Biores Technol. 2013, 129: 351-359.

Leung CCJ, Cheung ASY, Zhang AYZ, Lam KF, Lin CSK: Utilisation of waste bread for fermentative succinic acid production. Biochem Eng J. 2012, 65: 10-15.

Li X, Xu H, Wu Q: Large-scale biodiesel production from microalga Chlorella protothecoides through heterotrophic cultivation in bioreactors. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007, 98: 764-771.

Chi Z, Zheng Y, Jiang A, Chen S: Lipid production by culturing oleaginous yeast and algae with food waste and municipal wastewater in an integrated process. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2011, 165: 442-453.

Kim JH, Lee JC, Pak D: Feasibility of producing ethanol from food waste. Waste Manage. 2011, 31: 2121-2125.

Yan S, Yao J, Yao L, Zhi Z, Xi C, Wu J: Fed batch enzymatic saccharification of food waste improves the sugar concentration in the hydrolysates and eventually the ethanol fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae H058. Braz Arch Biol Technol. 2012, 55: 183-192.

Claassen PA, Budde MA, López-Contreras AM: Acetone, butanol and ethanol production from domestic organic waste by solventogenic clostridia. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000, 2: 39-44.

Hayek M, Shriner RL: Hydrolysis of starch by sulfurous acid. Ind Eng Chem. 1944, 33: 1001-1003.

Lam W-C, Pleissner D, Lin SKC: Production of fungal glucoamylase for glucose production from food waste. Biogeosciences. 2013, 3: 651-661.

Jin F-M, Kishita A, Moriya T, Enomoto H: Kinetics of oxidation of food wastes with H2O2 in supercritical water. J Supercrit Fluids. 2001, 19: 251-262.

Norouzian D, Akbarzadeh A, Scharer JM, Moo Young M: Fungal glucoamylases. Biotechnol Adv. 2006, 24: 80-85.

Du C, Lin SKC, Koutinas A, Wang R, Dorado P, Webb C: A wheat biorefining strategy based on solid-state fermentation for fermentative production of succinic acid. Biores Technol. 2008, 99: 8310-8315.

Wang R, Shaarani SM, Godoy LC, Melikoglu M, Vergara CS, Koutinas A, Webb C: Bioconversion of rapeseed meal for the production of a generic microbial feedstock. Enzyme Microb Tech. 2010, 47: 77-83.

Dorado MP, Lin SKC, Koutinas A, Du C, Wang R, Webb C: Cereal-based biorefinery development: utilisation of wheat milling by-products for the production of succinic acid. J Biotechnol. 2009, 143: 51-59.

Fan KW, Chen F, Jones EBG, Vrijmoed LLP: Utilization of food processing waste by Thraustochytrids. Aquatic Mycology across the Millenium. Edited by: Hyde KD, Ho WH, Pointing SB. 2000, Hong Kong: Fungal Diversity Press, 185-194.

de Swaaf ME, de Rijk TC, Eggink G, Sijtsma L: Optimisation of docosahexaenoic acid production in batch cultivations by Crypthecodinium cohnii. Prog Ind Microbiol. 1999, 35: 185-192.

Li P, Miao X, Li R, Zhong J: In situ biodiesel production from fast-growing and high oil content Chlorella pyrenoidosa in rice straw hydrolysate. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011, doi:10.1155/2011/141207

Pleissner D, Wimmer R, Eriksen NT: Quantification of amino acids in fermentation media by isochratic HPLC analysis of their α-hydroxy acid derivates. Anal Chem. 2011, 83: 175-181.

Pleissner D, Eriksen NT: Effects of phosphorous, nitrogen, and carbon limitation on biomass composition in batch and continuous flow cultures of the heterotrophic dinoflagellate Crypthecodinium cohnii. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012, 109: 2005-2016.

Foley PM, Beach ES, Zimmerman JB: Algae as a source of renewable chemicals: opportunities and challenges. Green Chem. 2011, 13: 1399-1405.

Lipinski ES: Chemicals from biomass. Science. 1981, 212: 1465-1471.

Fogassy G, Ke P, Figueras F, Cassagnau P, Rouzeau S, Courault V, Gelbard G, Pinel C: Catalyzed ring opening of epoxides: application to bioplasticizers synthesis. Appl Catal A. 2011, 393: 1-8.

Gallezot P: Conversion of biomass to selected chemical products. Chem Soc Rev. 2012, 41: 1538-1558.

Lu Y, Larock RC: Aqueous cationic polyurethane dispersions from vegetable oils. ChemSusChem. 2010, 3: 329-333.

Blanc B, Bourrel A, Gallezot P, Haas T, Taylor P: Starch-derived polyols for polymer technologies: preparation by hydrogenolysis on metal catalysts. Green Chem. 2000, 2: 89-91.

Scott E, Peter F, Sanders J: Biomass in the manufacture of industrial products-the use of proteins and amino acids. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007, 75: 751-762.

Venus L, Richter K: Production of lactic acid from barley: strain selection, phenotypic and medium optimization. Eng Life Sci. 2006, 6: 492-500.

Deshpande M, Daniels L: Evaluation of sophorolipid biosurfactant production by Candida bombicola using animal fat. Biores Technol. 1995, 54: 143-150.

Shah V, Jurjevic M, Badia D: Utilization of restaurant waste oil as a precursor for sophorolipid production. Biotechnol Prog. 2007, 23: 512-515.

Bumbak F, Cook S, Zachleder V, Hauser S, Kovar K: Best practices in heterotrophic high-cell-density microalgal processes: achievements, potential and possible limitations. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011, 91: 31-46.

Theriault RJ: Heterotrophic growth and production of xanthophylls by Chlorella pyrenoidosa. Appl Microbiol. 1965, 13: 402-416.

Shi X-M, Chen F: High-yield production of lutein by the green microalga Chlorella protothecoides in heterotrophic fed-batch culture. Biotechnol Prog. 2002, 18: 723-727.

Graverholt OS, Eriksen NT: Heterotrophic high-cell-density fed-batch and continuous-flow cultures of Galdieria sulphuraria and production of phycocyanin. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007, 77: 69-75.

Eriksen NT: Production of phycocyanin-a pigment with applications in biology, biotechnology, foods and medicine. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008, 80: 1-14.

Oi VT, Glazer AN, Stryer L: Fluorescent phycobiliprotein conjugates for analyses of cells and molecules. J Cell Biol. 1982, 93: 981-986.

Prasanna R, Sood A, Suresh A, Nayak S, Kaushik B: Potentials and applications of algal pigments in biology and industry. Acta Bot Hung. 2007, 49: 131-156.

Romay C, Armesto J, Remirez D, González R, Ledon N, Garcia I: Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of C-phycocyanin from blue-green algae. Inflamm Res. 1998, 47: 36-41.

Metting FB: Biodiversity and application of microalgae. J Ind Microbiol. 1996, 17: 477-489.

Miao X, Wu Q: Biodiesel production from heterotrophic microalgal oil. Biores Technol. 2006, 97: 841-846.

Puhan S, Saravanan N, Nagarajan G, Vedaraman N: Effect of biodiesel unsaturated fatty acid on combustion characteristics of a DI compression ignition engine. Biomass Bioenerg. 2010, 34: 1079-1088.

Harun R, Danquah MK, Forde GM: Microalgal biomass as a fermentation feedstock for bioethanol production. J Chem Technol Biot. 2010, 85: 199-203.

Geun Goo B, Baek G, Jin Choi D, Il Park Y, Synytsya A, Bleha R, Ho Seong D, Lee C-G, Kweon Park J: Characterization of a renewable extracellular polysaccharide from defatted microalgae Dunaliella tertiolecta. Biores Technol. 2013, 129: 343-350.

Šoštarič M, Klinar D, Bricelj M, Golob J, Berovič M, Likozar B: Growth, lipid extraction and thermal degradation of the microalga Chlorella vulgaris. New Biotechnol. 2012, 29: 325-331.

Cheng C-H, Du T-B, Pi H-C, Jang S-M, Lin Y-H, Lee H-T: Comparative study of lipid extraction from microalgae by organic solvent and supercritical CO2. Biores Technol. 2011, 102: 10151-10153.

Lotero E, Liu Y, Lopez DE, Suwannakarn K, Bruce DA, Goodwin JG: Synthesis of biodiesel via acid catalysis. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2005, 44: 5353-5363.

Bligh EG, Dyer WJ: A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959, 37: 911-917.

Soh L, Zimmerman J: Biodiesel production: the potential of algal lipids extracted with supercritical carbon dioxide. Green Chem. 2011, 13: 1422-1429.

Haas MJ, Wagner K: Simplifying biodiesel production: the direct or in situ transesterification of algal biomass. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2011, 113: 1219-1229.

Patil PD, Gude VD, Mannarswamy A, Cooke P, Nirmalakhandan N, Lammers P, Deng S: Comparison of direct transesterification of algal biomass under supercritical methanol and microwave irradiation conditions. Fuel. 2012, 97: 822-831.

Patil PD, Reddy H, Muppaneni T, Schaub T, Holguin FO, Cooke P, Lammers P, Nirmalakhandan N, Li Y, Lu X, Deng S: In situ ethyl ester production from wet algal biomass under microwave-mediated supercritical ethanol conditions. Biores Technol. 2013, 139: 308-315.

Tran D-T, Yeh K-L, Chen C-L, Chang J-S: Enzymatic transesterification of microalgal oil from Chlorella vulgaris ESP-31 for biodiesel synthesis using immobilized Burkholderia lipase. Biores Technol. 2012, 108: 119-127.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Biomass funding from the Ability R&D Energy Research Centre (AERC) at the School of Energy and Environment in the City University of Hong Kong. We are also grateful to the donation from the Coffee Concept (Hong Kong) Ltd. for the ‘Care for Our Planet’ campaign, as well as a grant from the City University of Hong Kong (Project No. 7200248). Authors acknowledge the Innovation and Technology Fund from the Innovation and Technology Commission (ITS/353/12) in Hong Kong.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they do not have any competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

DP contributed to the writing of the manuscript. CSKL assisted in the revision of manuscript. The final version was read and approved by both authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pleissner, D., Lin, C.S.K. Valorisation of food waste in biotechnological processes. sustain chem process 1, 21 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2043-7129-1-21

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2043-7129-1-21