Abstract

Background

To retrospectively access outcome and prognostic parameters of linear accelerator-based stereotactic radiosurgery in brain metastases from malignant melanoma.

Methods

Between 1990 and 2011 140 brain metastases in 84 patients with malignant melanoma (median age 56 years) were treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. At initial stereotactic radiosurgery 48 % of patients showed extracerebral control. The median count of brain metastases in a single patient was 1, the median diameter was 12 mm. The median dose applied was 20 Gy/80 % isodose enclosing.

Results

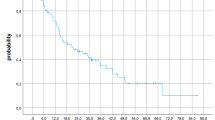

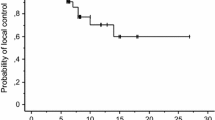

The median follow-up was 7 months and the median overall survival 9 months. The 6-, 12- and 24 month overall survival rates were 71 %, 39 % and 25 % respectively. Cerebral follow-up imaging showed complete remission in 20 brain metastases, partial remission in 39 brain metastases, stable disease in 54 brain metastases, progressive disease in 24 brain metastases and pseudo-progression in 3 brain metastases. Median intracerebral control was 5.3 months and the 6- and 12-month intracerebral progression-free survival rates 48 % and 38 %, respectively. Upon univariate analysis, extracerebral control (log-rank, p < 0.001), the response to stereotactic radiosurgery (log-rank, p < 0.001), the number of brain metastases (log-rank, p = 0.007), the recursive partitioning analysis class (log-rank, p = 0.027) and the diagnosis-specific graded prognostic assessment score (log-rank, p = 0.011) were prognostic for overall survival. The most common clinical side effect was headache common toxicity criteria grade I. The most common radiological finding during follow-up was localized edema within the stereotactic radiosurgery high dose region.

Conclusion

Stereotactic radiosurgery is a well-tolerated and effective treatment option for brain metastases in malignant melanoma and was able to achieve local remissions in several cases. Furthermore, especially patients with controlled extracerebral disease and a low count of brain metastases seem to benefit from this treatment modality. Prospective trials analysing the effects of combined stereotactic radiosurgery and new systemic agents are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The predicted 2012 standardized disease rate for malignant melanoma (MM) in Germany for women is 15.6 and for men 16.9 per 100.000 persons, respectively [1]. Even though incidence rates worldwide have increased over the past decades, recent developments indicate stabilization in some high-risk countries [2]. Risk factors for the development of brain metastases (BM) are for example positive sentinel lymph nodes and primary tumor ulceration [3, 4]. Unfortunately, the prognosis with BM from MM is poor and varies between a median overall survival of 3.5 months after whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT) in case of multiple BM [5] and an actuarial median survival of 10.6 months after stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) of single BM [6]. Another well-established approach is the resection of BM [7, 8] while upcoming systemic therapies have not shown to be adequately effective in BM from MM [9]. Prognostic factors include the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group recursive partitioning analysis (RTOG-RPA) class [10], diagnosis-specific Graded Prognostic Assessment (ds-GPA) score [11] and serum-lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) values [12]. This retrospective analysis was focused on patients with BM from MM treated with SRS to evaluate outcome and SRS-related side effects.

Methods

Patient characteristics

Between 1990 and 2011 181 patients with BM from MM were treated with linear accelerator (Linac)-based SRS at the Department of Radiation Oncology at the University Hospital of Heidelberg. Eighty-four patients with available imaging follow-up were included in this analysis; the remaining 97 patients without imaging follow-up were excluded from analysis. At initial SRS 48 % of patients showed extracerebral control. The median count of BM in a single patient was 1 and the median diameter 12 mm. Thirty-eight patients had > 1 BM treated with SRS. LDH levels were not evaluated on a regular basis. Further patient characteristics are found in Table 1.

Radiotherapy and follow-up

SRS applied a median dose of 20 Gy on the enclosing 80 % isodose. SRS was performed Linac-based using 6-mega electron volt (MeV) photon beams with either a round collimator or individually shaped by a micro-multileaf collimator. Head fixation was ensured by Scotchcast-masks. Patients were regularly followed by clinical examinations and imaging procedures as computer tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Salvage treatments consisted of whole brain radiotherapy, surgical resection of the BM, and chemo- or more recently immunotherapy.

Evaluation and statistics

The toxicity was graded according to the Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE Version 4). The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to estimate survival curves. Univariate analysis included age (>/< median age), gender, localization of the BM (infra- vs. supratentorial), number of BM (total and grouped 1 vs. 2–3 vs. >3), response to SRS (remission (including complete and partial remission) vs. stable disease vs. progressive disease), size of BM (>/< median), extracerebral tumor control (yes vs. no), Karnofsky performance score (90–100 vs. 70–80 vs. <70), RPA (1 vs. 2 vs. 3), ds-GPA (2 vs. 3 vs. 4), WBRT during follow-up (yes vs. no) and clinical symptoms prior to SRS (yes vs. no). Multivariate analysis was performed with the Cox-regression model (backwards stepwise, p out >0.1). Multivariate analysis included the significant factors from univariate analysis: extracerebral control, ds-GPA score, RPA class, number of BM and response to SRS. Significance was defined as p < 0.05. Correlation of the treatment response after SRS in patients with 2 or more BM treated with SRS was analyzed using Spearman correlation coefficient. All time estimates began with the date of SRS. The statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Informed consent was obtained. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Heidelberg (S-004/2012).

Results

Outcome

The median OS was 9 months (95 % CI 8–10 months). The 6-, 12- and 24-months OS rates were 71 %, 39 % and 25 % (Fig. 1). At the last follow-up examination in July 2014, 11 patients were still alive. Causes of death were documented in 6 patients only: intracerebral progression in 4 patients and peritoneal carcinomatosis as well as pulmonary embolism in 1 patient each. The median follow-up time was 7 months (range, 0.2–199.2 months). Cerebral follow-up imaging showed a complete remission (CR) in 20 BM, a partial remission (PR) in 39 BM, stable disease (SD) in 54 BM, progressive disease (PD) in 24 BM and a histopathologically proven pseudo-progression in 3 BM. The median intracerebral control time was 5.3 months resulting in 6- and 12-months intracerebral progression-free survival rates of 48 % and 38 % (Fig. 2).

Prognostic factors

The results of the uni- and multivariate analyses are presented in Table 2. In univariate analyses, extracerebral tumor control (p < 0.001, uncontrolled 6.8 months vs. controlled 12.4 months), response to SRS (p < 0.001, progressive disease 4.3 months vs. stable disease 8.3 months vs. remission 13.3 months), number of BM (linear p = 0.007; grouped p = 0.005, n > 3 8.3 months vs. n = 2–3 5 months vs. n = 1 12.4 months), RPA class (p = 0.027, class 1 37.8 months vs. class 2 8.3 months versus class 3 3.3 months) and ds-GPA (p = 0.011, score 2 5 months vs. score 3 8.8 months vs. score 4 12.4 months, Fig. 3) were prognostic for overall survival (OS). In multivariate analysis extracerebral tumor control (p < 0.001), response to SRS (p < 0.001) and the grouped number of BM (p = 0.006) were prognostic. In patients with 2 or more BM treated with SRS the treatment response after SRS correlated significantly (Spearman correlation coefficient 0.684).

Side effects

Acute side effects within the first three days after SRS were seen in 6 % (n = 5): headache CTCAE °I was reported by 3 patients, muscle weakness CTCAE °II by 1 patient and temporary worsening of pre-existing paresthesias CTCAE °I by one other patient. Acute side effects within the first 3 months were documented in 13 patients (15 %; Table 3). Late (>3 months) side effects were documented in 2 patients (Table 3).

Discussion

This retrospective single-center analysis reports on possible prognostic factors, outcome and toxicity of SRS in 140 BM from MM treated between 1990 and 2011 and followed by cerebral imaging. Our intention was to help find ways to improve prognosis, morbidity and mortality in patients with BM from MM. Literature on treatment outcome is summarized in Table 4.

Liew et al. reported in 2011 on 333 consecutive patients treated with Gamma Knife SRS for BM from MM [13]. The median follow-up was 3.8 months and the median survival 5.6 months. In the analysis published by Bernard et al. encompassing 54 patients with BM from MM, the median survival after SRS for intact BM (n = 34) was 4 months, compared to 13 months after prior resection (n = 20) of the BM [14]. Recently, Marcus and co-workers reported a median OS of 6.9 months in 135 patients treated with SRS for BM from MM [12]. In comparison our results showing a median OS of 9 months and 12- and 24 months OS rates of 39 % and 25 %, respectively, are superior to these prior reports. This difference might be explained by a selection bias for follow-up imaging in our analysis or different approaches in systemic therapy in case of tumor progression.

With respect to local control Liew et al. reported a median progression-free survival of 30 months with progression-free survival rates of 63 % at 12 months and 57 % at 24 months after SRS [13]. Follow-up imaging in 259 patients with 1226 BM showed CR in 6 %, PR in 23 %, SD in 61 % and PD in 10 %. In the cohort of Lwu et al. on 36 patients treated with Gamma Knife SRS (median prescription dose 21 Gy) for BM, 20 patients suffered from melanoma [15]. The local control at 12 months was 75 % for melanoma patients. In our cohort comparable response rates were observed. The diagnosis of pseudo-progression in all of our 3 cases was based on histopathological examination following surgical resection of the lesion.

Regarding the number of BM, Liew et al. reported patients suffering from single BM to have median survival of 8.2 months, compared to 4.1 months with multiple BM [13]. This prognostic difference is in accordance with our results, which showed significantly shorter survival times with increasing number of BM. On the other hand, in the smaller patient group of Marcus et al., the number of BM had no significant impact on survival [12]. In the cohort of Bernard et al., an increasing number of BM showed a trend towards shorter survival [14]. This difference might be due to selection bias caused by different treatment approaches in the different clinics.

The adverse events documented in our cohort were comparable to previous reports. One case of focal alopecia was due to superficial location of the BM and not unexpected when reviewing the treatment plan and dose distribution. One case with imaging diagnosis of central nervous system necrosis grade I was followed without intervention. Silk et al. reported on patients treated with ipilimumab and radiation therapy for BM from MM. In their comparison group intratumoral haemorrhage happened in 12.5 % of cases, radiation necrosis in 3 cases [16]. In an analysis by Kondziolka the haemorrhage rate was up to 50 % in BM from MM [17]. The diagnosis of pseudo-progression of cerebral lesions following radiation treatment is challenging. Hoefnagels et al. as well as Mitsuya et al. recommended perfusion MRI (PWI) to differentiate between progression and pseudo-progression [18, 19]. Recently Wiggenraad et al. analysed 10 patients with pseudo-progression following SRS of BM and concluded that consecutive MRIs using cine-loops may improve understanding of pseudo-progression [20]. However, in their analysis on PWI, magnetic resonance spectroscopy and amino-acid positron emission tomography Kickingereder et al. concluded that technical limitations were problematic, comparative studies warranted and stereotactic biopsies on structural MRI highly reliable to differentiate between tumor progression and radiation-induced changes [21].

However, patients with cerebrally metastasized MM have a poor prognosis. Potential for improvement might be found in the availability of new systemic therapies and the combination of those with SRS. In recent years systemic treatment options such as for example the development of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated Protein 4 antibodies or BRAF inhibitors improved outcome in metastasized MM. Combined with SRS these systemic agents might provide yet further improvement, but they may also be a reason for major concern due to potential harmful interactions. A retrospective analysis by Tazi et al. suggested that survival of patients with BM from MM treated with ipilimumab combined with SRS might be comparable to those without BM [17]. Furthermore, an abscopal effect of SRS after ipilimumab has been reported prolonging the median survival to 22.4 months [22]. Silk et al. reported a five time increase in the median survival after combination of ipilimumab and SRS suggesting synergistic effects for this treatment approach [16]. Recently a study on 30 patients treated with BRAF inhibitor and Gamma knife-SRS did not show increased toxicity rates [23]. On the other hand increased skin reactions have been reported for the combination of BRAF inhibitors and radiotherapy demanding caution in combining new systemic agents and radiation treatments [24, 25].

Regarding limitations of our study, the reader should acknowledge its retrospective character and the changes in systemic treatments during its 21 year recruiting time. Prognostic markers like LDH levels or ulceration of the primary tumor were not accessible due to the retrospective character. In general, regular radiotherapeutic follow-up examinations in patients with metastasized MM could be challenging for example due to a decline in performance status caused by progressive disease, long distance to the radiation clinic or organizational difficulties in case of further treatments elsewhere. Even though all available data were carefully reviewed, a bias, for example in patient selection for MR imaging during follow-up could not be excluded. In recent years MRI capacities have increased and therefore more precise imaging information during follow-up is available than in earlier years. Furthermore, causes of death were documented in a minority of patients only. On the other hand our study has a reasonable number of treated BM and increases the available evidence for treating BM from MM with SRS. Further evaluations of prognostic markers and the immunological effects of systemic agents as ipilimumab in combination with SRS or whole brain radiation are warranted. Therefore we prepared a prospective observational trial that started recruitment recently.

Conclusion

SRS is a well-tolerated and effective treatment option in brain metastases from malignant melanoma. Furthermore, remissions of BM could be achieved in some cases. Especially patients with controlled extracerebral disease and low count of BM seem to benefit from this treatment modality. Prospective trials analysing the effects of a treatment approach combining new systemic agents and SRS are warranted. A prospective observational study to analyse the immunologic effects of ipilimumab as well as SRS is underway.

Abbreviations

- ALM:

-

Acral lentiginous melanoma

- AMM:

-

Amelanotic melanoma

- BM:

-

Brain metastases

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CR:

-

Complete remission

- CT:

-

Computer tomography

- CTCAE:

-

Common toxicity criteria for adverse events

- DS-GPA:

-

Diagnosis-specific graded prognostic assessment

- Gy:

-

Gray

- KPS:

-

Karnofsky performance score

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- Linac:

-

Linear accelerator

- MeV:

-

Mega electron volt

- MM:

-

Malignant melanoma

- mm:

-

Millimeter

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- n. a.:

-

Not available

- NM:

-

Nodular melanoma

- n. r.:

-

Not reported

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PD:

-

Progressive disease

- PR:

-

Partial remission

- PWI:

-

Perfusion MRI

- RPA:

-

Recursive partitioning analysis

- RTOG:

-

Radiation Therapy Oncology Group

- SD:

-

Stable disease

- SRS:

-

Stereotactic radiosurgery

- SSM:

-

Superficial spreading melanoma

- WBRT:

-

Whole brain radiotherapy

References

Krebs in Deutschland 2007/2008. 8. Ausgabe. Robert Koch-Institut (Hrsg) und die Gesellschaft der epidemiologischen Krebsregister inDeutschland e.V. (Hrsg). Berlin, 2012.

Erdmann F, Lortet-Tieulent J, Schüz J, Zeeb H, Greinert R, Breitbart EW, et al. International trends in the incidence of malignant melanoma 1953-2008--are recent generations at higher or lower risk? Int J Cancer. 2013;132:385–400.

Zakrzewski J, Geraghty LN, Rose AE, Christos PJ, Mazumdar M, Polsky D, et al. Clinical variables and primary tumor characteristics predictive of the development of melanoma brain metastases and post-brain metastases survival. Cancer. 2011;117:1711–20.

Bottoni U, Clerico R, Paolino G, Ambrifi M, Corsetti P, Calvieri S. Predictors and survival in patients with melanoma brain metastases. Med Oncol. 2013;30:466.

Hauswald H, Dittmar J-O, Habermehl D, Rieken S, Sterzing F, Debus J, et al. Efficacy and toxicity of whole brain radiotherapy in patients with multiple cerebral metastases from malignant melanoma. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7:130.

Herfarth KK, Izwekowa O, Thilmann C, Pirzkall A, Delorme S, Hofmann U, et al. Linac-based radiosurgery of cerebral melanoma metastases. Analysis of 122 metastases treated in 64 patients. Strahlenther Onkol. 2003;179:366–71.

Sampson JH, Carter Jr JH, Friedman AH, Seigler HF. Demographics, prognosis, and therapy in 702 patients with brain metastases from malignant melanoma. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:11–20.

Fife KM, Colman MH, Stevens GN, Firth IC, Moon D, Shannon KF, et al. Determinants of outcome in melanoma patients with cerebral metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1293–300.

Flanigan JC, Jilaveanu LB, Chiang VL, Kluger HM. Advances in therapy for melanoma brain metastases. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:264–81.

Gaspar L, Scott C, Rotman M, Asbell S, Phillips T, Wasserman T, et al. Recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) of prognostic factors in three Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) brain metastases trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:745–51.

Sperduto PW, Chao ST, Sneed PK, Luo X, Suh J, Roberge D, et al. Diagnosis-specific prognostic factors, indexes, and treatment outcomes for patients with newly diagnosed brain metastases: a multi-institutional analysis of 4,259 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:655–61.

Marcus DM, Lowe M, Khan MK, Lawson DH, Crocker IR, Shelton JW, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival after radiosurgery for brain metastases from melanoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37(6):580-84.

Liew DN, Kano H, Kondziolka D, Mathieu D, Niranjan A, Flickinger JC, et al. Outcome predictors of Gamma Knife surgery for melanoma brain metastases. Clinical article J Neurosurg. 2011;114:769–79.

Bernard ME, Wegner RE, Reineman K, Heron DE, Kirkwood J, Burton SA, et al. Linear accelerator based stereotactic radiosurgery for melanoma brain metastases. J Cancer Res Ther. 2012;8:215–21.

Lwu S, Goetz P, Monsalves E, Aryaee M, Ebinu J, Laperriere N, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for the treatment of melanoma and renal cell carcinoma brain metastases”. Oncol Rep. 2013;29(2):407–12.

Silk AW, Bassetti MF, West BT, Tsien CI, Lao CD. Ipilimumab and radiation therapy for melanoma brain metastases. Cancer Med. 2013;2:899–906.

Kondziolka D, Bernstein M, Resch L, Tator CH, Fleming JF, Vanderlinden RG, et al. Significance of hemorrhage into brain tumors: clinicopathological study. J Neurosurg. 1987;67:852–7.

Hoefnagels FWA, Lagerwaard FJ, Sanchez E, Haasbeek CJA, Knol DL, Slotman BJ, et al. Radiological progression of cerebral metastases after radiosurgery: assessment of perfusion MRI for differentiating between necrosis and recurrence. J Neurol. 2009;256:878–87.

Mitsuya K, Nakasu Y, Horiguchi S, Harada H, Nishimura T, Bando E, et al. Perfusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging to distinguish the recurrence of metastatic brain tumors from radiation necrosis after stereotactic radiosurgery. J Neurooncol. 2010;99:81–8.

Wiggenraad R, Bos P, Verbeek-de Kanter A, LycklamaANijeholt G, van Santvoort J, Taphoorn M, et al. Pseudo-progression after stereotactic radiotherapy of brain metastases: lesion analysis using MRI cine-loops. J Neurooncol. 2014;119:437–43.

Kickingereder P, Dorn F, Blau T, Schmidt M, Kocher M, Galldiks N, et al. Differentiation of local tumor recurrence from radiation-induced changes after stereotactic radiosurgery for treatment of brain metastasis: case report and review of the literature. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:52.

Grimaldi AM, Simeone E, Giannarelli D, Muto P, Falivene S, Borzillo V, et al. Abscopal effects of radiotherapy on advanced melanoma patients who progressed after ipilimumab immunotherapy. Onco Immunology. 2014;3:e28780.

Gaudy-Marqueste C, Carron R, Delsanti C, Loundou A, Monestier S, Archier E, et al. On demand Gamma-Knife strategy can be safely combined with BRAF inhibitors for the treatment of melanoma brain metastases. Annals of Oncology. 2014;25(10):2086–91.

Merten R, Hecht M, Haderlein M, Distel L, Fietkau R, Heinzerling L, et al. Increased skin and mucosal toxicity in the combination of vemurafenib with radiation therapy. Strahlentherapie und Onkologie. 2014;190(12):1169–72.

Schulze B, Meissner M, Wolter M, Rödel C, Weiss C. Unusual acute and delayed skin reactions during and after whole-brain radiotherapy in combination with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: Two case reports. Strahlenther Onkol. 2014;190:229–32.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

HH: analysis and interpretation of data, writing manuscript. AS: collection, analysis and interpretation of data. JD: critical revision for important intellectual content, interpretation of data. SEC: substantial contributions to conception and design; critical revision for important intellectual content; final approval for publication. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hauswald, H., Stenke, A., Debus, J. et al. Linear accelerator-based stereotactic radiosurgery in 140 brain metastases from malignant melanoma. BMC Cancer 15, 537 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1517-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1517-1