Abstract

Background

Full-thickness macular hole (FTMH) is a rare complication in retinitis pigmentosa (RP) patients and may increase intraoperative challenges. Furthermore, lens capsular flap transplantation and inverted internal limiting membrane (ILM) flap were reported to close complicated FTMH successfully. Here, we present a case of bilateral advanced RP complicated by a FTMH treated with a novel lens capsular flap transplantation and inverted internal limiting membrane flap.

Case presentation

A 46-year-old presented to our hospital with a complaint of progressively blurred vision and metamorphopsia in both eyes. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography revealed a FTMH with retinoschisis in the right eye and another FTMH in the left eye. ILM peeling with inverted ILM flap technique was performed on the right eye and ILM peeling with anterior lens capsular flap technique was performed on the left eye. Post-operative follow-up showed successful closure of the FTMH and improved vision in both eyes.

Conclusions

In our present case, flap-assisted techniques for retinitis pigmentosa with macular hole result in excellent visual and anatomic outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a type of inherited retinal disease with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 4000 [1]. RP causes loss of peripheral vision and night blindness; thus, evaluation and preservation of central vision are critical [1, 2]. Macular abnormalities are not uncommon among RP patients and were found to be more frequent than the general population, with a reported prevalence of 7.4−43.8 % [3,4,5]. Cystoid macular edema (CME), epiretinal membrane (ERM), and vitreomacular traction (VMT) are the most common macular abnormalities in RP, with a prevalence of 5–20 % [3,4,5,6,7,8], 0.6−27.3 % [3,4,5, 8], 0.8−5 % [3, 5, 8] respectively, in the general RP population.

Compared to CME, ERM, and VMT, full-thickness macular hole (FTMH) is a relatively rare complication of RP, with a reported prevalence of 0.5−4.5 % [3,4,5,6, 8] and only several small case series have been reported. Surgical treatment for FTMH in patients with RP is more difficult than that in general patients. Dysfunction of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) in RP may lead to a failure of the pumping mechanism, causing hydration of the foveolar with progressive enlargement of the hole and leakage of fluid through the RPE [9, 10]. Furthermore, pigmentary changes in the macula area may further increase the challenges intraoperatively.

Recently, an inverted internal limiting membrane (ILM) flap was successfully applied for complicated FTMH with good results [11]. Furthermore, lens capsular flap transplantation was reported to successfully close refractory FTMHs and posterior retinal holes, serving as an alternative when previous ILM flaps fail [12, 13]. Herein, we present a case of RP complicated with bilateral FTMH who underwent surgery using inverted flap and lens capsular flap techniques. In addition, we conducted a comprehensive literature review on the treatment and outcome of past cases of RP with FTMH. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report regarding flap technique-assisted surgeries for complicated FTMH with RP.

Case presentation

A 46-year-old male presented to our hospital with a complaint of progressively blurred vision and metamorphopsia in both eyes. He also suffered from night blindness since childhood and had been diagnosed with RP with a positive family history. Otherwise, he denied any history of other systemic diseases.

At presentation, his best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/400 in the right eye and 20/400 in the left eye (Snellen). Anterior segment examination revealed dense nuclear sclerosis in both eyes. With dilated fundoscopy, both eyes presented advanced RP, including peripheral retinal atrophy with bone spicule-shaped pigmentation in the mid-periphery, waxy pallor of the optic nerve head, and attenuation of retinal vessels. Severe macular involvement with profound pigmentary change was also noted in both eyes. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography revealed a stage IV FTMH of 320 μm in diameter with retinoschisis in the right eye and another stage IV FTMH of 495 μm in diameter in the left eye. The axial length was 23.24 mm in his right eye and 23.43 mm in his left eye. Electroretinography showed diminished waves, both in rods and cones, in both eyes.

In his right eye with cataract, FTMH, and retinoschisis, 25-gauge pars plana vitrectomy, ERM/ILM peeling with inverted ERM/ILM flap technique, and C3F8 gas tamponade were performed combined with phacoemulsification and posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation under retrobulbar anesthesia. Indocyanine green (ICG) staining was used intraoperatively for ILM peeling.

In his left eye, 25-gauge pars plana vitrectomy, ERM/ILM peeling with anterior lens capsular flap technique, and C3F8gas tamponade were performed combined with phacoemulsification and posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation under retrobulbar anesthesia. The technique of lens capsular flap was similar to that presented by Yang in 2016 [12]. In brief, the circular anterior capsular flap was harvested by continuous circular capsulorhexis, and then it was stained with 0.125 % ICG and preserved in a balanced salt solution. Afterward, the flap was cut into a size a little larger than that of the FTMH using scissors and was translocated to the FTMH using micro forceps. Both surgical procedures were demonstrated on video (see Additional file 1).

Additional file 1.

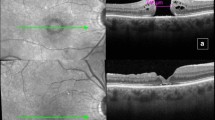

Three months after surgery of the right eye, OCT confirmed successful closure of the FTMH, and BCVA improved to 20/100. One month after surgery of the left eye, OCT confirmed successful closure of the FTMH, and BCVA improved to 20/125. The pre-operative and post-operative imaging are shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

Pre-operative and post-operative changes of the right eye. (A) Pre-operative electroretinography. (B) Fundus photograph before surgery. (C) Fundus photograph 3 months after surgery. (D) Fundus autofluorescence after surgery. (E) Horizontal optical coherence tomography before surgery. (F) Horizontal optical coherence tomography 3 months after surgery

Pre-operative and post-operative changes of the left eye. (A) Pre-operative electroretinography. (B) Fundus photograph before surgery. (C) Fundus photograph 1 month after surgery. (D) Fundus autofluorescence after surgery. (E) Horizontal optical coherence tomography before surgery. (F) Horizontal optical coherence tomography 1 month after surgery

Discussion and conclusion

FTMH is a rare but sight-threatening condition in RP patients. Among the macular interface abnormalities in patients with RP, CME and ERM are the most common findings, while FTMH is less common, with a prevalence of 0.5−4.5 % [3,4,5,6, 8]. Given the relative rarity of FTMH in RP, to date, only small sample-sized studies have reported cases of FTMH in RP, and no large-size cohort study was found in our comprehensive literature search.

According to our literature analysis, ten studies that reported the surgical course and outcome of RP patients with FTMH were identified and analyzed (Table 1). A total of 24 patients and 24 eyes were included in this study. Among the 24 eyes that underwent vitrectomy and ILM peeling, 15 (62.5 %) patients had improved vision, 5 (20.8 %) remained unchanged, and 4 (16.7 %) worsened. Twenty (83.3 %) cases had complete closure of the hole, three (12.5 %) cases failed to close the FTMH, and 1 (4.2 %) reopened 2 years later. Vitreous surgery has been suggested by several studies as a proper treatment for RP patients with FTMH, in which most patients achieved vision improvement and FTMH closure. Patients with complications, such as posterior vitreous detachment, retinal detachment, and CME, did not hinder the success of FTMH closure. It was presumed that failed closure and worsened vision was due to retinal thinning and atrophy at the macula caused by long-term damage to the photoreceptor or RPE loss [5, 14]. In general, FTMH is commonly treated with vitrectomy with or without ILM peeling. Closure rates were reported to reach 90 %; however, failure of hole closure is higher in cases with high myopia [15, 16], chronic FTMH [17] and diabetic retinopathy [18].

In our present case, though the axial length was only 23.24 mm in his right eye and 23.43 mm in his left eye, large posterior staphyloma with significant chorioretinal atrophy was noted in his both eyes. The configuration was quite similar to the high myopia-related FTMH. Surgical repair for this kind of FTMH is challenging because of the poor retinal adhesion to the underlying surface and the posterior staphyloma that may produce an inverse traction to impede retinal adhesion [26,27,28]. However, to seal the FTMHs is important in order to maintain the remnant central vision and prevent the further degeneration of photoreceptors over the long-term [14, 21]. ILM flap technique was proven to be effective in this circumstance [29,30,31]. In his right eye, tangential traction exerted by the ERM could be proposed as a causative factor in the development of a macular hole–related retinoschisis. Therefore, inverted flap technique was chosen to make sure the successful closure of FTMH with resolution of retinoschisis. The post-operative vision improved to 20/100 from 20/400 with concomitant removal of cataract.

A diameter of FTMH over 500 μm could be considered a risk factor for unclosure after primary vitrectomy and flap-related techniques can improve the closure rate [32, 33]. However, if ILM was not available such as being peeled in previous surgeries or other causes, lens capsular flap transplantation, which has been first introduced by Yang in 2016, could be a good alternative to overcome the aforementioned difficulties. The lens capsule is thicker and has a higher density than the ILM, enabling it to settle down easier on the retinal surface and be directed to the target place [12, 34]. For his left eye, we chose to use lens flap for his left eye rather than inverted ILM flap in order not to damage the atrophic retina in the circumstance of severely pigmentary change which hindered the visualization of ILM. The post-operative vision improved to 20/125 from 20/400 with concomitant removal of cataract and cell migration was shown beneath the lens flap.

The pathophysiology of FTMH formation in RP remains unclear. Multifactorial pathogenesis is widely proposed in several studies [4]. It is hypothesized that degenerative vitreous, with the collapse of the vitreous gel and posterior vitreous detachment, may lead to vitreomacular interface changes, which is likely to contribute to CME formation. A case reported that Muller cells, glial cells, and fibroblasts were found in the removed membrane, suggesting that the FTMH was caused by vitreous degeneration due to RP [25]. Other pathophysiologic changes in RP, including a breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier, Muller cell dysfunction and swelling, failure of RPE pumping, and antiretinal antibodies, were also presumed to lead to CME formation [35]. As a result, rupture and posterior fusion of the cysts of a CME may facilitate FTMH formation [6, 25, 36,37,38]. High myopia with globe elongation macular retinoschisis may also predispose the formation of FTMH [21].

In conclusion, FTMH is a rare macular abnormality in patients with RP. Previous studies have shown successful outcomes with pars plana vitrectomy. We propose the first case report that flap-assisted techniques may serve as an alternative for advanced RP with FTMH. More studies are warranted in the future to verify the anatomical effectiveness and functional benefits of flap-assisted techniques for RP with FTMH.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- RP:

-

Retinitis pigmentosa

- ILM:

-

Internal limiting membrane

- FTMH:

-

Full-thickness macular hole

- CME:

-

Cystoid macular edema

- ERM:

-

Epiretinal membrane

- VMT:

-

Vitreomacular traction

- RPE:

-

Retinal pigment epithelium

- BCVA:

-

Best corrected visual acuity

- ICG:

-

Indocyanine green

References

Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa. The Lancet. 2006;368(9549):1795–809.

Panagiotou ES, Papathomas T, Nikopoulos K, Koukoula S, Quinodoz M, Rehman AU, et al. Management of full-thickness macular hole in a genetically confirmed case with Usher Syndrome. Ophthalmology therapy. 2020;9(3):677–84.

Testa F, Rossi S, Colucci R, Gallo B, Di Iorio V, della Corte M, et al. Macular abnormalities in Italian patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(7):946–50.

Triolo G, Pierro L, Parodi MB, De Benedetto U, Gagliardi M, Manitto MP, et al. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography findings in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmic Res. 2013;50(3):160–4.

Hagiwara A, Yamamoto S, Ogata K, Sugawara T, Hiramatsu A, Shibata M, et al. Macular abnormalities in patients with retinitis pigmentosa: prevalence on OCT examination and outcomes of vitreoretinal surgery. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89(2):e122-5.

Giusti C, Forte R, Vingolo EM. Clinical pathogenesis of macular holes in patients affected by retinitis pigmentosa. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2002;6(2–3):45–8.

Hirakawa H, Iijima H, Gohdo T, Tsukahara S. Optical coherence tomography of cystoid macular edema associated with retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128(2):185–91.

Fragiotta S, Rossi T, Carnevale C, Cutini A, Tricarico S, Casillo L, et al. Vitreo-macular interface disorders in retinitis pigmentosa. Graefe’s archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie 2019;257(10):2137–46.

Gentile RC, Landa G, Pons ME, Eliott D, Rosen RB. Macular hole formation, progression, and surgical repair: case series of serial optical coherence tomography and time lapse morphing video study. BMC Ophthalmology. 2010;10(1):24.

Berinstein DM, Hassan TS, Williams GA, Margherio RR, Ruby AJ, Garretson BR. Surgical repair of full-thickness idiopathic macular holes associated with significant macular drusen. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(12):2233–9.

Michalewska Z, Michalewski J, Adelman RA, Nawrocki J. Inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique for large macular holes. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(10):2018–25.

Chen SN, Yang CM. Lens capsular flap transplantation in the management of refractory macular hole form multiple etiologies. Retina. 2016;36(1):163–70.

Chen Y-C, Yang C-M, Chen S-N. Lens capsular flap in the management of posterior retinal hole associated retinal detachment in high myopic eyes with previous internal limiting membrane peeling: 3 case reports. Medicine. 2019;98(29):e16422-e.

Yan F, Xia F-J, Jiang F, Yu HG. Visual and morphological outcomes of vitreomacular traction syndrome in retinitis pigmentosa treated by vitrectomy. International journal of ophthalmology. 2018;11(8):1411–5.

Ichibe M, Yoshizawa T, Murakami K, Ohta M, Oya Y, Yamamoto S, et al. Surgical management of retinal detachment associated with myopic macular hole: anatomic and functional status of the macula. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136(2):277–84.

Wu TT, Kung YH. Comparison of anatomical and visual outcomes of macular hole surgery in patients with high myopia vs. non-high myopia: a case-control study using optical coherence tomography. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;250(3):327–31.

Thompson JT, Sjaarda RN, Lansing MB. The results of vitreous surgery for chronic macular holes. Retina. 1997;17(6):493–501.

Yeh PT, Cheng CK, Chen MS, Yang CH, Yang CM. Macular hole in proliferative diabetic retinopathy with fibrovascular proliferation. Retina. 2009;29(3):355–61.

Vingolo EM, Valente S, Gerace E, Spadea L, Nebbioso M. Macular hole in retinitis pigmentosa patients: microincision vitrectomy with polydimethylsiloxane as possible treatment. Eye. 2015;29(5):699–702.

Jin Z-B, Gan D-K, Xu G-Z, Nao-I N. Macular hole formation in patients with retinitis pigmentosa and prognosis of pars plana vitrectomy. Retina. 2008;28(4):610–4.

Liu J, Lyu J, Zhang X, Zhao P. Lamellar hole-associated epiretinal membrane is a common feature of macular holes in retinitis pigmentosa. Eye. 2020;34(4):643–9.

Ratra D, Raval V. Surgery for macular holes associated with unusual concomitant pathologies. Oman journal of ophthalmology. 2013;6(2):112–5.

Enani L, Kozak I, Abdelkader E. A case of unilateral retinitis pigmentosa associated with full thickness macular hole. Middle East African journal of ophthalmology. 2017;24(2):113–5.

García-Fernández M, Castro-Navarro J, Bajo-Fuente A. Unilateral recurrent macular hole in a patient with retinitis pigmentosa: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7(1):69.

Amemiya K, Takahashi M, Nishida A, Matsumura M, Hayakawa M, Honda Y. A macular hole in the eye of a young patient with retinitis pigmentosa. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 2002;106(4):236–42.

Oshima Y, Ikuno Y, Motokura M, Nakae K, Tano Y. Complete epiretinal membrane separation in highly myopic eyes with retinal detachment resulting from a macular hole. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126(5):669–76.

Seike C, Kusaka S, Sakagami K, Ohashi Y. Reopening of macular holes in highly myopic eyes with retinal detachments. Retina. 1997;17(1):2–6.

Akiba J, Konno S, Yoshida A. Retinal detachment associated with a macular hole in severely myopic eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128(5):654–5.

Oleñik A, Rios J, Mateo C. Inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique for macular holes in high myopia with axial length ≥ 30 mm. Retina. 2016;36(9):1688–93.

Sasaki H, Shiono A, Kogo J, Yomoda R, Munemasa Y, Syoda M, et al. Inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique as a useful procedure for macular hole-associated retinal detachment in highly myopic eyes. Eye. 2017;31(4):545–50.

Matsumae H, Morizane Y, Yamane S, Yanagisawa S, Sakurai T, Kobori A, et al. Inverted internal limiting membrane flap versus internal limiting membrane peeling for macular hole retinal detachment in high myopia. Ophthalmol Retina. 2020;4(9):919–26.

Wrzesińska D, Nowomiejska K, Nowakowska D, Toro MD, Bonfiglio V, Reibaldi M, et al. Secondary vitrectomy with internal limiting membrane plug due to persistent full-thickness macular hole OCT-angiography and microperimetry features: Case series. Journal of Ophthalmology. 2020;2020:2650873.

Ma FY, Xi RJ, Chen PF, Hao YH. Free autologous internal limiting membrane transplantation in the treatment of large macular hole. Int J Ophthalmol. 2019;12(5):848–51.

Peng J, Chen C, Jin H, Zhang H, Zhao P. Autologous lens capsular flap transplantation combined with autologous blood application in the management of refractory macular hole. Retina. 2018;38(11):2177–83.

Strong S, Liew G, Michaelides M. Retinitis pigmentosa-associated cystoid macular oedema: pathogenesis and avenues of intervention. British journal of ophthalmology. 2017;101(1):31–7.

Takezawa M, Tetsuka S, Kakehashi A. Tangential vitreous traction: a possible mechanism of development of cystoid macular edema in retinitis pigmentosa. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland NZ). 2011;5:245–8.

Ozdek S, Ozdogan S, Sezgin T, Gurelik G. Bilateral disc edema and unilateral macular hole in a patient with retinitis pigmentosa. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2006;16(3):487–90.

Rao PK, Shah G, Blinder KJ. Bilateral macular hole formation in a patient with retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 2002;33(2):152–4.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Y.L. was involved in the literature search, collection of clinical data and writing of the original draft. T.C.C. was involved in interpretations of the patient data and literature review, revision and approval of the manuscript. C.M.Y., C.H.Y. and F.R.H. were involved in the review and approval of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The written informed consent to publish this information was obtained from study participants, and the proof of consent can be requested at any time. The patient gave written consent for their personal or clinical details along with any identifying images to be published in this study.

Consent for publication

The written informed consent to publish this information was obtained from study participants, and the proof of consent can be requested at any time. The patient gave written consent for their personal or clinical details along with any identifying images to be published in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, CY., Yang, CM., Yang, CH. et al. Flap technique-assisted surgeries for advanced retinitis pigmentosa complicated with macular hole: a case report and literature review. BMC Ophthalmol 21, 322 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-021-02082-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-021-02082-3