Abstract

Background

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) is considered well accepted screening tool for postpartum depression (PPD). The objective of the study was to validate the EPDS as a screening tool for postpartum depression in Kathmandu, Nepal.

Methods

A hospital based cross sectional study using EPDS was conducted among 346 mothers between 4 and 14 weeks of postpartum period. All the participants were examined by psychiatrist for possible clinical PPD diagnosis using International Classification of Disease tenth revision (ICD-10). Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value were calculated for validation of EPDS. The best cut off point for Nepalese version of EPDS was identified and area of the receiver operating characteristics curve was calculated.

Results

The overall prevalence of PPD was 17.1 %.The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of the Nepalese version EPDS was found to be 92, 95.6, 77 and 99.3 % respectively. The best cut-off point of EPDS for screening of PPD was found to be 12/13 and the area of the curve was 0.98 (95 % CI 0.970–0.994, p = 0.001).

Conclusions

The prevalence of PPD is not that far from the previous studies of Nepal. Nepali version of EPDS was acceptable and the study demonstrates good validity, thus EPDS can be used as valid screening tool for PPD for early detection, prompt treatment and to prevent possible consequences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Postpartum depression is defined as an episode of non-psychotic depression according to standardized diagnostic criteria with onset within 1 year of childbirth [1]. Approximately 50–80 % of women suffered from maternal sadness in the puerperal period, with about 20 % of those women develop postpartum depression [2]. However, there is a wide variation in prevalence of postpartum depression from almost affecting 8–50 % of postnatal mothers [3–7] in different countries. The prevalence of PPD is estimated to be higher in low and middle income countries than for high income countries primarily as many women don’t seek help or tell others about their feelings [8–12]. British Medical Bulletin, 2012 reported that low income countries such as Nepal and Malaysia had prevalence of PPD below 13 % and in other low income countries it ranges from 13 to 50 % [7]. The studies conducted in Nepal showed the prevalence of PPD ranging from 4.9 to 19.4 % [13–15]. The differences in the magnitude of prevalence may be due to transcultural variations and interpretation of symptoms and also socio-economic variables [16].

Postpartum Depression can have several consequences which includes maternal death due to suicide [17], the mother infant relationship [18], psychological development of child [19], infant nutrition [20] and infant growth [21]. Postpartum depression is infrequently diagnosed and indeed treated, though its significant incidence and morbidity [22]. Depressive symptoms are dismissed as they mimic normal physiologic changes [23–25] and formerly used to be ignored in health care services [26]. The effects of postnatal depression on the mother, her marital relationship, and her children make it an important condition to diagnose, treat and prevent [1].

The routine use of screening scales for the purpose of identifying symptoms of depression is an effective, simple and economical way to identify women at risk [27]. There are some instruments designed to measure PPD which includes: The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale [28], Beck Depression Scale (BDI) [29], Zung Self Rating Scale [30], the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) [31] and the Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ20) [32]. In the postpartum period, the EPDS has been the most widely used scale to identify postpartum depression [4, 33–35]. Cox, Halden and Sagovsky, in 1987 identified EPDS as fully acceptable tool for detection of PPD with simple method of scoring. It is a 10-item self-report questionnaire in which women are asked to rate how they have felt in the previous 7 days and each question is scored 0–3 resulting in total score range of 0–30. The tool has satisfactory sensitivity and specificity and was also sensitive to change in severity of depression over time [36].

With the development of EPDS, it has been validated and used in many countries [4, 34, 35, 37, 38]. The sensitivity observed in the validation studies presented variations ranging from 65 to 100 %, while the specificity with 49–100 % in range with different cut-off points [4, 34, 35, 37, 39, 40]. In the validation studies done in Nepal there is also wide range of variation in sensitivity with 68–100 % whereas less variation in specificity 93–94 % [13, 41]. The great variability of results among the different studies was due to variations in methodology used, diagnostic criteria and different weeks of postpartum [4, 34, 35, 37, 39–41].

Validation of EPDS is an important endeavor that provides reliability of the instrument when next version other than original English is used. As there is wide variation in sensitivity of EPDS in various validation studies conducted in Nepal, this study aimed to validate original English version of EPDS into Nepali version in order to measure the accuracy of the EPDS to screen postpartum depressive symptoms.

Methods

The aim, design and setting of the study

Descriptive cross-sectional design was used to validate the EPDS. The study was conducted at the Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital (TUTH) in Kathmandu, Nepal. It is the tertiary level facility situated in capital of Nepal.

Participants

The study population consisted of 4–14 weeks postpartum mothers attending child immunization clinic. Women suffering from severe medical illness, personal and family history of mood disorder were excluded as physical symptoms (Insomnia, anorexia, decreased concentration and pain etc.) could mimic those of depression and may bias the sample. Women with mental retardation were also excluded because of the probability of interference in the process of informed consent and even also during the data collection.

Sample size

The sample was chosen by systematic random sampling method from those who registered in the clinic before immunization of children. The required sample size was calculated from

Z = 1.96, P = 8 % = 0.08, q = 1 − p = 0.92, allowable error L = 3 % = 0.03.

The prevalence estimated by various study in Nepal was 12 and 5 % respectively [13, 14]. Hence, prevalence of 8 was estimated by taking an average. The sample size was 346 at 95 % confidence limit and power of 80 with 10 % of non-response rate.

Data collection tools and technique

The EPDS was used to detect depression as a screening tool. The EPDS is a ten item self-report questionnaire. Items 1 and 2 assess anhedonia; item 3: self-blame; item 4: anxiety; item 5: fear or panic; item 6: inability to cope; item 7: difficulty sleeping; item 8: sadness; item 9: tearfulness and item 10: self-harm ideas. Responses are scored as 0, 1, 2 and 3 according to the increasing severity of the symptoms. Total score is calculated by adding each score of the each 10 items. The value of score can range from 0 to 30 [27].

Forward translation from original English version of EPDS to Nepali version was done by two bilingual psychiatrist of TUTH. Then backward translation from Nepali version to English version was done by a group of professional translators. The back translated English version was reviewed by native English speaker. In order to make scale sensitive to culture and social strata, conceptual and linguistic equivalence was considered during the translation process. The principal investigator pre-tested the tool in Thapathali Maternity Hospital by using interview technique. The reliability of the Nepalese version EPDS scale was determined by reliability index i.e. Cronbach’s alpha and found to be 0.74 which showed the acceptable range of reliability. The tool was well accepted and did not demand any modification. The data collection was then carried out by principal investigator by using EPDS as a screening tool. After administration of EPDS, the diagnostic interview was taken by a psychiatrist using ICD-10 as gold standard. The ICD-10 diagnostic protocol was translated into Nepali language. The psychiatrist was blinded to the initial screening results. The diagnostic interview was taken in same day to avoid possible fluctuation of mental status in the postpartum period. The structured questionnaire was used to collect the demographic information. All the participants agreed to participate in the study and none of the respondent withdrew.

Data management and analysis

Data was compiled and checked for completeness and entered into EPI-INFO version 3.5.1. The entered data were exported to Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 20. Descriptive analysis was done for demographic variables. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of the translated version of EPDS were obtained to determine the validity of EPDS. The identification of best cut off score was done by cross tabulating the value of sensitivity and 1-specificity for each point. The accuracy of the screening tool at best cutoff point was identified from ROC curve by computing area under curve.

Ethical consideration

The study was approved by Institutional Review Board of Institute of Medicine, Tribhuvan University. The purpose of the study was explained and written consent was taken from all the participants.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study population

The socio- demographic data were described in terms of age, ethnicity, educational status, occupation and parity. Of all participants, mean age was 22.75 (SD = 4.51) with more than half (51 %) being Brahmin/Khsetri in ethnicity. The majority of respondent (57 %) completed their higher secondary and above. About half of the participants (49 %) were engaged in domestic/household work. Fourty-four percent respondent had only one child (Table 1).

Prevalence of PPD

Out of 346 participants, 59 were found to be suffering from PPD by EPDS at the cutoff point of 12/13. Hence, the prevalence rate of PPD was found to be 17.1 % (Table 2).

Validation of EPDS

The EPDS scores were cross tabulated with the actual PPD status of the participants from diagnostic interview. From this the corresponding sensitivity (proportion of depressed mothers according to ICD-10 criteria that were correctly identified by EPDS), specificity (proportion of non-depressed mothers correctly identified as such by EPDS), positive predictive value (proportion of true positives among all positives identified by EPDS) and negative predictive value (proportion of true negatives among all negatives identified by EPDS) were calculated. These are the measures of determining the validity of the scale for screening of the PPD (Table 3).

Here, sensitivity = TP/TP + FN = 46/46 + 4 = 0.92 = 92 %

Specificity = TN/TN + FP = 283/283 + 13 = 95.6 %

Positive predictive value (PPV) = TP/TP + FP = 46/46 + 13 = 0.77 = 77 %

Negative predictive value (NPV) = TN/TN + FN = 287/287 + 4 = 99.3 %

The sensitivity between 80 and 90 % is considered quite well and the screening test can correctly identify those who have depression. Similarly, specificity 95 % is also considered quite good to identify correctly those who do not have depression. Hence, the EPDS is identified as the valid tool to measure the PPD in Nepalese context in this study.

The EPDS cutoffs point

Screening tests use cutoff points to assess the threshold above which the tests are reliably accurate to identify the presence of given condition. In case of EPDS, the sum total score are computed against the clinical diagnosis and the levels of sensitivity (true positive) and 1-specificity (false positive) were assessed for each score (Table 4).

It can be noted from above table EPDS cutoff levels of 12 and 13 are close in their sensitivity (true positive) and 1-specificity (false positive) values. Hence, the cutoff point of the screening test was found at 12/13.

The ROC curve for the EPDS screening test

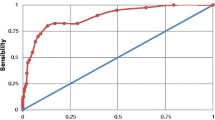

To determine whether this cutoff level should actually be considered as the cutoff for Nepalese version of EPDS in screening the PPD status, the receiver operating characteristics curve (ROC) was also computed (Fig. 1).

ROC curve for the screening of PPD by EPDS scale. Receiver operating characteristic curve for the EPDS screening test, demonstrating area under curve at chosen cutoff level i.e. (12/13). The area under curve was 0.982. Thus the Nepalese version of EPDS had accuracy of 98.2 % (95 % CI 0.970–0.994, p = 0.001) in screening for cases of PPD with the cutoff at 12/13. Hence, this cut off level can be considered optimum to define threshold level for depressive symptoms

Discussion

The present study showed the overall prevalence of 17.1 % with cutoff point of 12/13.The prevalence of the study was lower than the prevalence found by Budathoki (19.4 % at 6 weeks and 22.2 % at 10 weeks of postpartum) which was done in Kathmandu Medical College Teaching Hospital and Dhading District Hospital with cutoff point of >13 [15], whereas, the prevalence was higher than in the study done by Regmi (12 %) in tertiary level hospital [13]. The findings lie in between these two studies. The minor alteration in prevalence might be due to differences in the study methodology and diagnostic criteria and also due to variation in the sample size. The prevalence not essentially contradict with that of the other countries which includes Thailand (10 %) [35], New Zealand (17.1 %) [40], Pakistan (16.4 %) [42] and United Kingdom (10–15 %) [43]. The prevalence of this study was not that far with the studies of other countries though there is variation in social structure, different educational status, social support, economic status, availability of health services, parenting methods and more. However, several studies have found high rate of depression in low and middle income countries [8–12].

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of the Nepalese version EPDS found by this study was 92, 95.6, 77 and 99.3 % respectively at threshold level 12/13. The original English version of EPDS by Cox, identified sensitivity and specificity of 86 and 78 % respectively with threshold level above 12/13 [36]. The study done for validation of Nepalese version of EPDS by Regmi had shown sensitivity of 100 %, specificity of 92.6 %, positive predictive value of 41.6 % and negative predictive value of 100 % with cutoff point 12/13[13]. Also, an another study done in Nepal in 1999, had detected sensitivity of 68.3 %, specificity of 93.8 %, positive predictive value of 65 % and negative predictive value of 94.64 % at cut off point of 12/13 [41]. The hospital based study done in India, revealed the sensitivity of 92 % and specificity of 85 % [44] while the study done in urban slum of Karachi, Pakistan had shown sensitivity of 79 % and specificity of 74 % [42]. This study showed better psychometric properties than in the original English version EPDS by Cox et al., earlier Nepali language EPDS validation studies, studies from neighboring countries like India and Pakistan. This might be due to difference in methodology, translation process, sample size, diagnostic interview and timing of testing. The participants who visit health facilities of urban area are well educated and can have good understanding of translated version. In our study, more than two-third of participants were educated up to secondary level and above, so may have the greater emotional literacy and this might be the reason for good psychometric properties. However, the systemic study of Shrestha and colleagues found psychometric properties from low-and middle-income countries to be lower than that for the original English version of EPDS [45].

Having well defined cut off point appropriate at local setting is essential for accurate detection and estimation of PPD burden in the country. The cutoff point of Nepalese version of EPDS identified by this study was 12/13 which is similar with the previous studies done in Nepal by Regmi et al. and Nepal et al. [13, 41]. The cutoff score was also somewhat equivalent with the study from low and lower-middle-income countries like India (11/12) [44], Pakistan (13/14) [42], Mongolia (12/13) [46], Ghana (10/11) [47] and Zimbabwe (10/11) [48]. But the cutoff point was higher than the studies done in Ethiopia (5/6) [49], Nigeria (8/9) [50], Vietnam (3/4) [51] and Malawi (4/5) [52]. The variation in cutoff point score seen in different validation studies may be due to social and economic diversity, cultural norms and heterogeneities in sample characteristics. The higher EPDS cutoff score ensures the screening test has the best performance by identifying most cases so that a diagnostic or/and therapeutic intervention could be offered.

Culture sensitive translation, empirical validation, better psychometric properties and consistency of findings with national and international literature suggested that the Nepalese version of EPDS is valid instrument to screen the postpartum depressive symptoms. On the other hand, the study exhibited some limitations to be used in all settings of Nepal. As the sample was drawn from only one tertiary level hospital, the findings from this study may be limited to clinical setting and might have less generalizability in the culturally and socially diverse context.

Conclusion

From our result and those obtained from other studies it can be concluded that Nepalese version of the EPDS can be successfully used to screen the postpartum depression in Nepalese women. These findings might be the inferences for the future planning and implementation of maternal mental health programs and policies in low and lower-middle-income countries.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- EPDS:

-

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

- FN:

-

false negative

- FP:

-

false positive

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Diseases (Version 10)

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- PPD:

-

postpartum depression

- NPV:

-

negative predictive value

- PPV:

-

positive predictive value

- ROC:

-

receiver operating characteristics curve

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- TN:

-

true negative

- TP:

-

true positive

- TUTH:

-

Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital

References

Stewart DE, Robertson E, Dennis C-L, Grace SL, Wallington T. Postpartum depression: literature review of risk factors and interventions. Toronto: University Health Network Women’s Health Program for Toronto Public Health; 2003.

Miller LJ. Pospartum depression. JAMA. 2002;287:762–6.

Perfetti J, Clark R, Fillmore CM. Postpartum depression: identification, screening, and treatment. WMJ. 2004;103(6):56–63.

Teissedre F, Chabrol H. A study of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) on 859 mothers: detection of mothers at risk for postpartum depression. Encephale. 2004;30(4):376–81.

Suda S, Segi-Nishida E, Newton SS, Duman RS. A postpartum model in rat: behavioral and gene expression changes induced by ovarian steroid deprivation. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(4):311–9.

DelRosario G, Chang C, Lee E. Postpartum depression: symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment approaches. J Am Acad Phys Assist. 2013;26(2):50–4.

Parsons CE, Young KS, Rochat TJ, Kringelbach ML, Stein A. Postnatal depression and its effects on child development: a review of evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Br Med Bull. 2012;101:57–79. doi:10.1093/bmb/indro047.

Affonso DD, De AK, Horowitz JA, Mayberry LJ. An international study exploring levels of postpartum depressive symptomatology. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49(3):207–16.

Husain N, Bevc I, Husain M, Chaudhry I, Atif N, Rahman A. Prevalence and social correlates of postnatal depression in a low income country. Arch Women’s Mental Health. 2006;9(4):197–202.

Segre LS, O’Hara MW, Arndt S, Stuart S. The prevalence of postpartum depression. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(4):316–21.

Ross LE, McLean LM. Anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;6:1.

Hegde S, Latha KS, Bhat SM, Sharma PSVN, Kamath A, et al. Postpartum Depression: Prevalence and Associated Factors among Women in India. J Womens Health Issues Care. 2012;1:1. doi:10.4172/2325-9795.1000101.

Regmi SSW, Carter D, Grut W, Seear M. A controlled study of postpartum depression among Nepalese women: validation of the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale in Kathmandu. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7(4):378–82.

Dørheim SK. Depression and sleep in the postnatal period. A study in Nepal and Norway. Dissertation for the degree philosophiae doctor (Ph.D.) at University of Bergen, Norway. 2009.

Budhathoki N, Bhusal S, Ojha H, Pandey S, Basnet S. Violence against women by their husband and postpartum depression. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2012;10(22):176–80.

Halbreich U, Alarcon RD, Calil H, Douki S, Gaszner P, Jadresic E, Jasovic-Gasic M, Kadri N, Kerr-Correa F, Patel V, Sarache X, Trivedi JK. Culturally-sensitive complaints of depressions and anxieties in women. J Affect Disord. 2007;102(1–3):159–76.

Persaud A. Postnatal depression:a global public health perspective. Perspect Public Health. 2009;129:229–38.

Milgrom J, Ericksen J, McCarthy R, Gemmill AW. Stressful impact of depression on early mother–infant relations. Stress Health. 2006;22:229–38.

Murray L, Sinclair D, Cooper P, Ducournau P, Turner P, Stein A. The socio emotional development of 5-year-old children of postnatally depressed mothers. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;40:1259–71.

Rahman A, Patel V, Maselko J, Kirkwood B. The neglected ‘m’ in MCH programmes—why mental health of mothers is important for child nutrition. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:579–83.

Stewart RC. Maternal depression and infant growth: a review of recent evidence. Matern Child Nutr. 2007;3:94–107.

Lee DT, Yip AS, Chiu HF, Chung TK. Screening for postnatal depression using the double-test strategy. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:258–63.

Susman JL. Postpartum depressive disorders. J FamPract. 1996;43(6 Suppl):S17–24.

Hirst KP, Moutier CY. Postpartum major depression. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(8):926–33.

Beck CT. Postpartum depression: it isn’t just the blues. Am J Nurs. 2006;106(5):40–5 (quiz 50-1).

Gjerdingen DK, Yawn BP. Postpartum depression screening: importance, methods, barriers, and recommendations for practice. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20:280–8.

Cox JL, Chapman G, Murray D, Jones P. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in non-postnatal women. J Affect Disord. 1996;39(3):185–9.

Murray D, Cox JL. Screening for depression during pregnancy with the Edinburgh Depression Scale (EDDS). J Reprod Infant Psychol. 1990;8(2):99–107.

Kazantzis N, Pachana NA, Secker DL. Cognitive behavioral therapy for older adults: practical guidelines for the use of homework assignments. Cogn Behav Pract. 2003;10(4):324–32.

Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12(6):371–9.

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand S-L, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(06):959–76.

Gulamani SS, Premji SS, Azam SI, Kanji Z. Preterm birth a risk factor for postpartum depression in Pakistani women. Open J Depression. 2013;2(04):72.

Guedeney N, Fermanian J, Guelfi JD, Kumar RC. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and the detection of major depressive disorders in early postpartum: some concerns about false negatives. J Affect Disord. 2000;61(1–2):107–12.

Alvardo-Esquivel C, Sifuentes-Alvarez A, Salas-Martinez C, Martinez-Garcia S. Validation of the Edinburgh postpartum depression scale in a population of puerperal women in Mexico. Clin Pract Epidemiol Mental Health 2006; 2(33). doi:10.1186/1745-0179-2-33.

Pitanupong J, Liabsuetrakul T, Vittayanont A. Validation of the Thai Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for screening postpartum depression. Psychiatry Res. 2007;149(1–3):253–9.

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6.

Toreki A, Ando B, Dudas RB, Dweik D, Janka Z, Kozinszky Z, Kereszturi A. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale as a screening tool for postpartum depression in a clinical sample in Hungary. Midwifery. 2014;30(8):911–8. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2014.02.00.

Odalovic M, Tadic I, Lakic D, Nordeng H, Lupattelli A, Tasic L. Translation and factor analysis of structural models of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in Serbian pregnant and postpartum women—web-based study. Women Birth. 2015;28(3):e331–5.

Gibson J, McKenzie-McHarg K, Shakespeare J, Price J, Gray R. A systematic review of studies validating the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in antepartum and postpartum women. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119:350–64. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01363.x.

Ekeroma AJ, Ikenasio-Thorpe B, Weeks S, Kokaua J, Puniani K, Stone P, Foliaki SA. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale(EPDS) as a screening tool for postnatal depression in Samoan and Tongan women living in New Zealand. NZ Med J, NZMJ. 2012;125(1355):1175–8716. http://www.journal.nzma.org.nz/journal/125-1355.

Nepal MK, Sharma VD, Koirala NR, Khalid A, Shestha P. Validation of Nepalese version of Edinburgh postnatal depression scale in tertiary health care facilities, Nepal. J Psychiatry. 1999;1(1):46–50.

Nusrat Husain N, Asia Parveen A, Husain M, Saeed Q, Jafr F, Rahman R, Tomenson B, Chaudhry IB. Prevalence and psychosocial correlates of perinataldepression: a cohort study from urban Pakistan. Arch Womens Mental Health. 2011;14:395–403. doi:10.1007/s00737-011-0233-3.

Cox JL, Murray D, Chapman G. A controlled study of the onset, duration and prevalence of postnatal depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:27–31.

Patel V, Rodriges M, DeSouza N. Gender, poverty and postnatal depression: a study of mothers in Goa, India. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(1):43–7.

Shrestha DS, Pradhan R, Tran DT, Gualano RC, Fisher JR. Reliability and validity of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for detecting perinatal common mental disorders(PCMDS) among women in low-and lower-middle-income countries:a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:72.

Pollock JI, Manaseki-Holland S, Patel V. Detection of depression in women of child bearing age in non-western cultures: a comparison of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and self reporting questionnaire-20 in Mongolia. J Affect Disord. 2006;92(2–3):267–71.

Weobong B, Akpalu B, Doku V, Owusu-Agyel S, Hurt L, Kirkwood B, Prince M. The comparative validity of screening scales for postnatal common mental disorder in Kintampo, Ghana. J Affect Disord. 2009;113(1):109–17.

Chibanda D, Mangezi W, Tshimanga M, Woelk G, Rusakaniko P, Stranix-Chinabda L, Midzi S, Maldonodo Y, Shetty AK. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale among women in a high HIV prevalence area in urban Zimbabwe. Arch Womensment Health. 2010;13(3):201–6.

Hanlon C, Medhin G, Alem A, Araya M, Abdulahi A, Hughes M, Tesfaye M, Wondimagegn D, Patel V, Prince M. Detecting perinatal common mental disorders in Ethiopia: validation of the self-reporting questionnaire and Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. J Affect Disord. 2008;108(3):151–62.

Uwakwe R. Affective (depressive) morbidity in puerperal Nigerian women: validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Acta psychiatry Scand. 2003;107(4):209–16.

Tran TD, Tran T, La B, Lee D, Rosenthal D, Fisher J. Screening for perinatal common mental disorders in women in the north of Vietnam: a comparison of three psychometric instruments. J Affect Disord. 2011;133(1):281–93.

Stewart RC, Umar E, Tomenson B, Creed F. Validation of screening tools for antenatal depression in Malawi-A comparison of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and self reporting questionnaire. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(3):1041–7.

Authors’ contributions

BRB has worked on design of the work, literature review, data collection, analysis and interpretation, drafting and finalization of the article. BN has carried out the literature review and critical input in drafting the manuscript. CM supported in clinical examination of depressive symptoms by using ICD-10 and GT supported with analysis and finalization of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors deeply acknowledge all the staffs of Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital for their support and co-operation. Also authors wish to gratitude the patients for their participation.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

No more data are available.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Institutional Review Board of Tribhuvan University, Institute of Medicine.

Funding

Graduate Student Research Grant was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bhusal, B., Bhandari, N., Chapagai, M. et al. Validating the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale as a screening tool for postpartum depression in Kathmandu, Nepal. Int J Ment Health Syst 10, 71 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-016-0102-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-016-0102-6